Abstract

Neurofibromatosis (NF) is one of the most common genetic disorders. Inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, this phacomatosis is classified into two genetically distinct subtypes characterized by multiple cutaneous lesions and tumors of the peripheral and central nervous system. Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), also referred to as Recklinghausen's disease, affects about 1 in 3500 individuals and presents with a variety of characteristic abnormalities of the skin and the peripheral nervous system. Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2), previously termed central neurofibromatosis, is much more rare occurring in less than 1 in 25 000 individuals. Often first clinical signs of NF2 become apparent in the late teens with a sudden loss of hearing due to the development of bi-or unilateral vestibular schwannomas. In addition NF2 patients may suffer from further nervous tissue tumors such as meningiomas or gliomas. This review summarizes the characteristic features of the two forms of NF and outlines commonalities and distinctions between NF1 and NF2.

Introduction

In 1882 the German pathologist Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen for the first time described a series of patients with a combination of cutaneous lesions and tumors of the peripheral and central nervous system. Only in the 20th century neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), namely Recklinghausen's disease, and neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2), previously referred to as central neurofibromatosis, were distinguished from each other as two different autosomal dominantly inherited genetic disorders with common features [1-3]. Briefly, NF1 exposes a characteristical cutaneous phenotype including benign neurofibromas, which are mixed tumors composed of all cell types found in the peripheral nerves, hyperpigmented macules, termed café-au-lait macules, the so called axillary/inguinal freckling, as well as pigmented hamartomas of the iris, called Lisch nodules. NF2 on the other hand is mainly restricted to tumors of the central and peripheral nervous system, which are only seldomly accompanied by cutaneous disorders [4].

NF1 Clinical features

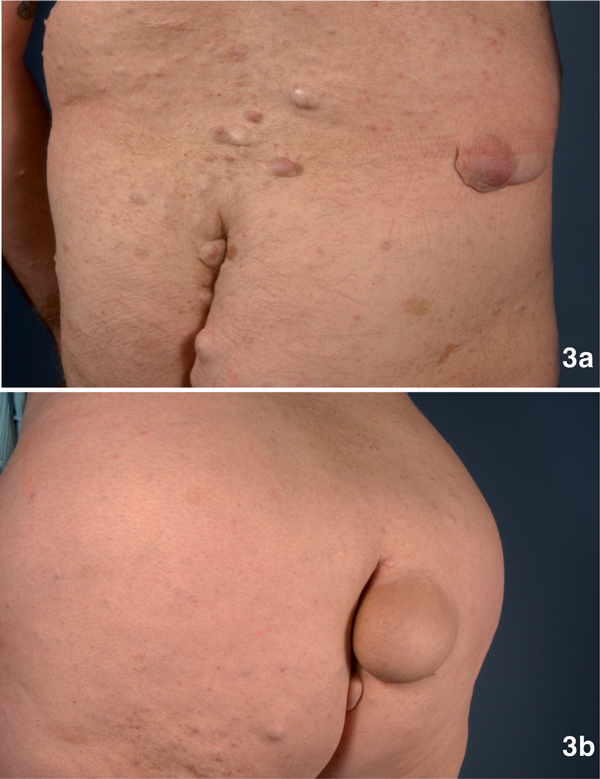

NF1 is considered as one of the most common genetic disorders in human with an incidence of 1/3500 individuals. In 1997, Gutmann and colleagues updated the diagnostic criteria for NF1 and NF2 [5]. Usually cutaneous manifestations are the first symptoms observed in NF1 patients [6]. Café-au-lait macules (CALMs) mainly develop in childhood and are found in almost all patients. CALMs present as light brown macules of about 10 to 40 mm in diameter with an ovoid shape and poorly circumscribed borders (Figure 1). Whereas the presence of ≥ 6 CALMs is defined as strong diagnostic criterion for NF1, additional features are mandatory for a definite diagnosis. A common feature is a characteristic axillary and/or inguinal freckling, which usually develops subsequently to CALMs and which is observed in 90% of all patients (Figure 2) [7]. The development of neurofibromas around or on peripheral nerves is a distinct symptom of NF 1 but is observed to a lesser extent also in NF2 patients [1]. Neurofibromas occur as either encapsulated dermal and subcutaneous tumors or as plexiform neurofibromas (Figure 3). Dermal and subcutaneous neurofibromas may cause little or no clinical symptoms but can be very disfiguring. Plexiform neurofibromas on the other hand, which are often congenital and can develop near nerve roots deep within the body, bear a 10% probability of malignant transformation. In cases of transformation the arising malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) have been shown to have a high metastatic potential [2,8-11]. Additional complications of plexiform neurofibromas may manifest as diffuse appearance and/or a tendency to expand along large segments of affected nerves, causing disfigurement and nerve dysfunction. Finally pigmented hamartomas of the iris, so called Lisch nodules, have to be mentioned as a characteristic ophthalmologic feature of NF1 [9].

Figure 1.

A 9-year old boy with NF 1 and multiple (n ≥ 6) café-au-lait macules.

Figure 2.

Characteristic axillary freckling of a 51-year old woman with NF 1.

Figure 3.

3a: Multiple neurofibromas with a maximum diameter of 4 cm on the back and gluteal region of a 46-year old male with NF1. 3b: A 6 cm in diameter measuring, disabling tumor in the gluteal region of a 51-year old woman with NF1.

NF2 Clinical Features

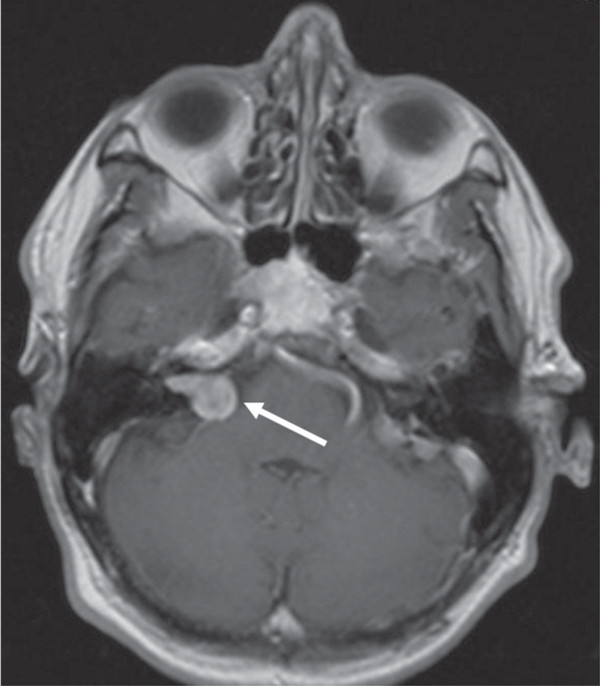

Whereas the clinical features of NF2 were initially described in the late 1800s, NF2 was first considered as a subtype of NF1. It took almost a hundred years for NF2 to be recognized as a self-contained entity. With an incidence of 1/25.000 it occurs much less frequently than NF1 [1]. Often the first clinical sign of NF2 is a sudden loss of hearing due to the development of bi-or unilateral vestibular schwannomas (Figure 4) [4]. These tumors occur on or around the vestibular branches of both auditory nerves. Unlike in NF1 patients, tumors in NF2 patients are uniformly benign. Nevertheless, these tumors can compress associated nerves and can cause considerable pain, nerve dysfunction and intracranial pressure. Further symptoms include a sudden onset of tinnitus or imbalance [10]. In addition, patients suffering from NF2 tend to develop further nervous tissue tumors such as meningiomas or gliomas. Dermal manifestations of schwannomas in NF2 patients are rare and can easily be confused with cutaneous neurofibromas [11]. In these cases, histopathological analysis is needed to reveal that these tumors consists of Schwann cells only. According to the 1991 NIH consensus criteria, the diagnosis of NF2 requires either the presence of bilateral vestibular schwannomas or a positive family history and an unilateral vestibular schwannoma in combination with either a menigioma, a glioma, a neurofibroma, a schwannoma, or posterior subcapsular opacities [10].

Figure 4.

A 63-year old man with a known history of NF2 presented with a progredient right-sided tinnitus and mild deafness. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a schwannoma of the vestibular portion (VS) of the right VIIIth cranial nerve.

Pathogenesis of NF1 and NF2

Inactivating mutations in the NF 1 and NF 2 genes, both, inherited and/or new germline mutations, are responsible for the development of the phenotypes of the diseases. The NF1 gene, located on 17q11.2, encodes for a protein also known as neurofibromin. Neurofibromin functions as a tumor suppressor by negatively regulating mitogenic Ras signalling through a GTPase activating protein (GAP), which is essential for NF 1-associated tumorigenesis. Particularly in neurocutaneous tissues, loss-of-function mutations result in increased Ras activity, causing increased proliferation and tumorigenesis [1,6,12-14].

The NF2 gene is located on 22q12.2 and encodes for merlin (schwannomin). The gene is much smaller than neurofibromin, which explains the much lower mutation rate of NF2 as compared to NF1. Merlin is considered to act as a regulator of growth, motility, and cellular remodeling by inhibiting the transduction of extracellular mitogenic signals such as CD44-mediated contact-dependent inhibition of proliferation. Correspondingly, Merlin has been shown to prevent epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signalling, known to induce cellular proliferation [1,15,18-20].

Treatment and management

Due to the variety and complexities of the manifestations of NF 1 and NF 2, an interdisciplinary approach is inevitable. Biannual screening examinations in childhood and then yearly thereafter are strongly recommended. Examinations should include the measurement of the head circumference as well as regular checks of blood pressure due to the risk for pheochromocytoma and renal abnormalities [18]. In childhood, behavioural and developmental parameters should be evaluated carefully for signs of learning disability and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [6,19]. In general, patients with NF 1 and NF 2 should undergo yearly neurologic and ophthalmologic examinations [5]. Treatment of severe and disfiguring tumors is usually performed by surgery. Notably, in 2008 Lantieri and colleagues reported the first face transplantation with a composite tissue allograft in a 29-year-old man with NF1 suffering from a massive, disfiguring plexiform neurofibroma diffusely infiltrating the middle and lower part of his face [20]. Although benign, the complete excision of tumors often remains a therapeutical endeavour due to their close association to nerves. It has to be noted that tumor-excision bears a high risk of recurrence [1,12]. Regarding NF2, the total surgical resection of vestibular schwannomas is a suitable therapeutic option and may result in definite tumor control. However, due to the frequently multilobulating and infiltrating character of the tumors, consecutive damage to the cochlear nerve or facial nerves is associated with a high risk of permanent hearing loss and other malfunctions [21]. Interestingly, a recent study by Phi and colleagues demonstrated a good 5-year tumor control and preserved serviceable hearing in approximately one-third of 30 NF2 patients with vestibular schwannomas treated with gamma knife radiosurgery [22]. Comparable studies report local control rates of 85% and 81% after 5 or 10 years, respectively, with hearing preservations of about 40%. In patients with a service able hearing before therapy the estimated risk of deafness is about 20% [10]. The authors promote radiosurgery as an effective and less invasive treatment option compared to standard surgical techniques [22]. Another notable therapeutic approach was reported by Plotkin and colleagues in 2008. The authors demonstrated the first successful laboratory-to-clinic translation of research by treating a 48-year-old NF2 patient with the EGFR-inhibitor erlotinib. Application of this novel targeted cancer drug caused a significant decrease in tumor volume and a re-establishment of useful hearing [10]. Taken together, this variety of novel and evidence-based therapeutic options raises new hope for affected patients.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ethelyn Rusnak Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Anesthesiology, State University of New York at Buffalo for reading and correcting the manuscript.

References

- McClatchey AI. Neurofibromatosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2007;2:191–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.2.010506.091940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccardi VM. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:1617–1627. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198112313052704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferner RE. Neurofibromatosis 1 and neurofibromatosis 2: a twenty first century perspective. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:340–351. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baser ME, Evans DG, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis 2. Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16:27–33. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200302000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann DH, Aylsworth A, Carey JC, Korf B, Marks J, Pyeritz RE, Rubenstein A, Viskochil D. The diagnostic evaluation and multidisciplinary management of neurofibromatosis 1 and neurofibromatosis 2. JAMA. 1997;278:51–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03550010065042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North K. Neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Med Genet. 2000;97:119–127. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(200022)97:2<119::AID-AJMG3>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainer S. A child with axillary freckling and cafe au lait spots. Cmaj. 2002;167:282–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada JG, Chakmakjian CG. Images in clinical medicine. Von Recklinghausen's disease and breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm050008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluwe L, Friedrich RE, Peiper M, Friedman J, Mautner VF. Constitutional NF1 mutations in neurofibromatosis 1 patients with malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:420. doi: 10.1002/humu.9193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frahm S, Mautner VF, Brems H, Legius E, Debiec-Rychter M, Friedrich RE, Knöfel WT, Peiper M, Kluwe L. Genetic and phenotypic characterization of tumor cells derived from malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors of neurofibromatosis type 1 patients. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;16:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagel C, Zils U, Peiper M, Kluwe L, Gotthard S, Friedrich RE, Zurakowski D, von Deimling A, Mautner VF. Histopathology and clinical outcome of NF1-associated vs. sporadic malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. J Neurooncol. 2007;82:187–192. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9266-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savar A, Cestari DM. Neurofibromatosis type I: genetics and clinical manifestations. Semin Ophthalmol. 2008;23:45–51. doi: 10.1080/08820530701745223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin SR, Singh MA, O'Donnell CC, Harris GJ, Mc-Clatchey AI, Halpin C. Audiologic and radiographic response of NF2-related vestibular schwannoma to erlotinib therapy. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5:487–491. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg JC, Scheithauer BW, Spinner RJ, Allen CM, Koutlas IG. Plexiform schwannoma: a clinicopathologic overview with emphasis on the head and neck region. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:633–640. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yohay K. Neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2. Neurologist. 2006;12:86–93. doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000195830.22432.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledbetter DH, Rich DC, O'Connell P, Leppert M, Carey JC. Precise localization of NF1 to 17q11.2 by balanced translocation. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;44:20–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace MR, Marchuk DA, Andersen LB, Letcher R, Odeh HM, Saulino AM, Fountain JW, Brereton A, Nicholson J, Mitchell AL. et al. Type 1 neurofibromatosis gene: identification of a large transcript disrupted in three NF1 patients. Science. 1990;249:181–186. doi: 10.1126/science.2134734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao GH, Chernoff J, Testa JR. NF2: the wizardry of merlin. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;38:389–399. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoles DR. The merlin interacting proteins reveal multiple targets for NF2 therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1785:32–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curto M, Cole BK, Lallemand D, Liu CH, McClatchey AI. Contact-dependent inhibition of EGFR signaling by Nf2/Merlin. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:893–903. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer K, Hasel C, Aschoff AJ, Henne-Bruns D, Wuerl P. Multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors and bilateral pheochromocytoma in neurofibromatosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3384–3387. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i24.3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayl AE, Moore BD. Behavioral phenotype of neurofibromatosis, type 1. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2000;6:117–124. doi: 10.1002/1098-2779(2000)6:2<117::AID-MRDD5>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantieri L, Meningaud JP, Grimbert P, Bellivier F, Lefaucheur JP, Ortonne N, Benjoar MD, Lang P, Wolkenstein P. Repair of the lower and middle parts of the face by composite tissue allotransplantation in a patient with massive plexiform neurofibroma: a 1-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2008;372:639–645. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samii M, Matthies C, Tatagiba M. Management of vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas): auditory and facial nerve function after resection of 120 vestibular schwannomas in patients with neurofibromatosis 2. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:696–705. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199704000-00007. discussion 705-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phi JH, Kim DG, Chung HT, Lee J, Paek SH, Jung HW. Radiosurgical treatment of vestibular schwannomas in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2: tumor control and hearing preservation. Cancer. 2009;115:390–398. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]