Abstract

Introduction

Perforation of the gall bladder represents a rare, but life-threatening complication of cholecystitis. Clinical presentation may vary between severe peritonism in acute perforation and absence of symptoms in subacute or chronic progression of perforation. Abdominal imaging like ultrasound or CT-scan are important tools for immediate diagnose of gall bladder perforation.

Case presentation

We report a case of a 30-year old female patient with end-stage kidney disease treated by continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) who was admitted to the emergency room with fever and mild abdominal pain. A type II gall bladder perforation by a solitary gall stone with development of a liver abscess was detected by abdominal ultrasound.

Conclusion

Gall bladder perforations are rare but have to be considered in patients with abdominal pain and fever. Abdominal ultrasound is a reliable tool to establish diagnosis.

Keywords: gall bladder perforation, liver abscess, CAPD

Introduction

A perforation of the gall bladder represents a life-threatening complication of cholecystitis, which occurred in historical study cohorts with an incidence of up to 10-15% [1-3] during acute cholecystitis. The establishment of early cholecystectomy and improvement of antibiotic therapy regimen have reduced the risk of gall bladder perforation in acute cholecystitis to 0.8-3.2% today [4-6].

Gall bladder perforation was classified by Niemeier into three categories [7]. Type I perforation presents as an acute disease with perforation into the free abdominal cavity, whereas type II perforation is characterized as a subacute stage with development of a pericholecystic abscess. Type III perforation arises in chronic cholecystitis with development of bilioenteric fistulae. Especially in chronic cholecystitis diagnosis of a gall bladder perforation may be delayed, when acute symptoms including peritonism are missing [8]. In these cases abdominal imaging by ultrasound or computed tomography is a useful tool.

We report on an oligosymptomatic gall bladder perforation into the liver due to cholecystolithiasis in a patient with peritoneal dialysis.

Case Presentation

A 30-year old female patient was admitted to the emergency unit with fever (40°C) for two days, mild pain in the right upper abdomen and deteriorated health condition. The patient was treated by dialysis since nine years because of a hemolytic-uremic syndrome, for the last seven years dialysis was done via continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. The patient had a history of arterial hypertension, nephrectomy because of a hypernephroma (pT1a) one year ago and a solitary concrement of the gall bladder (Figure 1). In the current laboratory results elevation of inflammatory parameters such as C-reactive protein (23 mg/dl, normal range <0.5 mg/dl) and white blood cell count (13,400 μl with 78% neutrophiles) were noticed. Physical investigation solely showed mild pain in the upper abdomen by deep palpation with no clear positive Murphy's sign, but was otherwise unremarkable.

Figure 1.

Large solitary concrement of the gall bladder with a maximal diameter of 27 mm, five years before onset of the gall bladder perforation.

The abdominal sonography revealed ascites and a multilayered, thickened wall of the gall bladder. The gall bladder wall facing toward the liver was missing and a large intrahepatic abscess with dislocation of a single bile stone of about 25 mm in diameter into the abscess cavity was visible (Figure 2). The intrahepatic abscess presented with inhomogenous echogenicity. Murphy's sign remained negative despite direct palpation of the gall bladder with the ultrasound transducer.

Figure 2.

Intrahepatic abscess with dislocation of the solitary concrement from the perforated gall bladder into the abscess cavity.

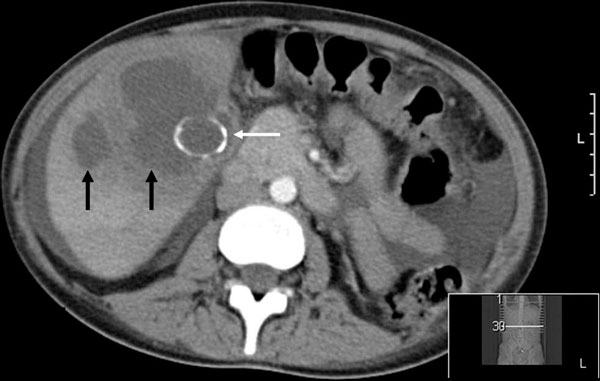

A CT-scan was performed for operative planning and confirmation of the diagnosis. A distinctive, hypodense intrahepatic abscess (Average 18HU) with hyperdense margins was detectable, the dislocated gall stone presented as a circular, hyperdense structure (Figure 3 and 4). An immediate cholecystectomy with debridement, stone extraction and lavage of the liver followed, concomitant antibiotic therapy was initiated.

Figure 3.

CT-scan correlating to US-images (see figure 2): The gall stone (white arrow) presents as a circular hyperdense structure within the intrahepatic abscess cavity (black arrows). Free intraabdominal fluid in continuous peritoneal dialysis.

Figure 4.

Coronary secondary reconstruction of CT-scan in axial phase. The intrahepatic abscess presents with hyperdense margins (black arrow). Clear illustration which accentuates the extent of the abscess and intrahepatic location of the partial calcified gall stone (white arrow). Free intraabdominal fluid with distal end of the peritoneal catheter in right lower abdomen (white arrowhead).

Histology showed a severe, hemorrhagic-erosive and ulcerative episode of a chronic-recurring cholecystitis with focal perforation of the gall bladder wall. Microbiology specimen confirmed E. coli and Candida glabrata. A prolonged convalescence developed with the need for changing the modus of dialysis from peritoneal dialysis to veno-venous hemodialysis. The patient was discharged from hospital 36 days after surgery. At that time, ultrasound of the liver still detected areas with low echogenicity. During follow-up the size of the irregular area decreased and was no longer visible three months after operation (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Follow-up sonography of liver abscess area. A: 8 days after operation (46 × 37 mm), B: 34 days after operation (46 × 25 mm), C: 68 days after operation (21 × 19 mm).

Discussion

A perforation of the gall bladder currently arises in 0.8-3.2% of the cases with acute onset of cholecystitis, but there is no data about the incidence of gall bladder perforation in chronic cholecystitis. Most cases present with a rupture into the peritoneal cavity. Development of an intrahepatic abscess represents a rare complication and is reported in literature only by several case reports. Both, perforation of the gall bladder or pyogenic liver abscess represent a life-threatening complication with mortality rates of 7% [4] and 5.6% [9] as shown by retrospective studies.

Gall bladder perforation is divided into three categories accordingg to progress (acute - subacute - chronic) and type of perforation (into free abdominal cavity - development of pericystic abscess - development of fistulae). This classification was described first by Niemeier in 1934. With regard to the histologically proven chronic-recurring cholecystitis and the development of an intrahepatic abscess this case has to be classified as a type II perforation. The incidence of clinical symptoms is variable and may be absent in chronic or subacute progression of disease. The performance of an abdominal ultrasound is an essential part of the work up of patients with fever and abdominal pain. In asymptomatic patients or cases with just mild abdominal pain gall bladder perforations may be diagnosed solely by imaging procedures.

Only two studies from 1994 and 2002 with low numbers of patients (combined n = 31) compared diagnostic findings between ultrasound and computed tomography in patients with gall bladder perforation. In comparison to the CT-scan, ultrasound seems to be less sensitive with 70% vs. 80% for the detection of the perforation [10,11]. Nevertheless, with regard to the improvement of resolution of modern sonographic imaging equipment, better results can be expected today. Therefore, abdominal ultrasound represents a reliable tool as imaging of first choice. CT scans are needed in cases of discrepancies between clinical symptoms and inconspicuous ultrasound as well as for better pre-operative planning subsequently to the sonographically proven perforation. CT scans have the advantage of a better representation of extensive findings because of the bigger field of view (FOV) and may demonstrate the extension of a lesion more clearly.

Patients who need CAPD show a significant higher incidence of peritonitis in comparison to the general population [12]. Nevertheless, there is no evidence in the literature that patients with CAPD show a higher incidence of cholecystitis or risk of gall bladder perforation than the general population even if some studies demonstrate that the prevalence of cholelithiasis may be higher in patients with dialysis than in non-dialysed control groups [13-16]. Analysis of the peritoneal fluid in this patient showed no white blood cells and lack of bacterial growth in culture. Therefore it seems to be unlikely that the peritoneal fluid was the origin for bacterial infection of the gall bladder. The onset of an acute on chronic cholecystitis with the development of a gall bladder perforation represented an independent disease with no relation to the continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis.

Interestingly, Murphy's sign as a clinical evidence of peritonism was not detectable. Usually, palpation of the gall bladder is painful when inflamed peritoneal layers rub on each other. However, when free fluid is present - as it is in patients with peritoneal dialysis - peritoneal layers are separated and Murphy's sign may vanish. Secondly, peritoneal layers may not have been affected in this patient because this was a covered perforation into the liver.

In conclusion, the present case shows that life threatening gall bladder ruptures have to be considered in patients with fever and only mild abdominal symptoms. In these patients ultrasound is a reliable tool to diagnose gall bladder perforation and avoids delay of treatment.

References

- Wallace R, Allen A. Acute cholecystitis. Arch Surg. 1943;43(5):762–72. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald JA. Perforation of the gallbladder associated with acute cholecystitis: 8-year review of 20 cases. Ann surg. 1966;164(5):849–52. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196611000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larmi TK, Kairaluoma MI, Junila J, Laitinen S, Stahlberg M, Fock HG. Perforation of the gallbladder. A retrospective comparative study of cases from 1946-1956 and 1969-1980. Acta Chir Scand. 1984;150(7):557–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanidis D, Sirinek KR, Bingener J. Gallbladder perforation: risk factors and outcome. J Surg Res. 2006;131(2):204–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.11.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiviluoto T, Siren J, Luukkonen P, Kivilaakso E. Randomised trial of laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy for acute and gangrenous cholecystitis. Lancet. 1998;351(9099):321–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08447-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedirli A, Sakrak O, Sozuer EM, Kerek M, Guler I. Factors effecting the complications in the natural history of acute cholecystitis. Hepato-gastroenterology. 2001;48(41):1275–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemeier OW. Acute Free Perforation of the Gall-Bladder. Ann Surg. 1934;99(6):922–4. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193499060-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derici H, Kara C, Bozdag AD, Nazli O, Tansug T, Akca E. Diagnosis and treatment of gallbladder perforation. World J" Gastroenterol. 2006;12(48):7832–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i48.7832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meddings L, Myers RP, Hubbard J, Shaheen AA, Laupland KB, Dixon E, A population-based study of pyogenic liver abscesses in the United States: incidence, mortality, and temporal trends. Am J Gastroenterol. pp. 117–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sood BP, Kalra N, Gupta S, Sidhu R, Gulati M, Khandelwal N. et al. Role of sonography in the diagnosis of gall bladder perforation. J Clin Ultrasound. 2002;30(5):270–4. doi: 10.1002/jcu.10071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim PN, Lee KS, Kim IY, Bae WK, Lee BH. Gallbladder perforation: comparison of US findings with CT. Abdom Imag. 1994;19(3):239–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00203516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport A. Peritonitis remains the major clinical complication of peritoneal dialysis: the London, UK, peritonitis audit 2002-2003. Perit Dial Int. 2009;29(3):297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojs R. Cholecystolithiasis in patients with end-stage renal disease treated with haemodialysis: a study of prevalence. Am J Nephrol. 1995;15(1):15–7. doi: 10.1159/000168796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm JS, Lee HL, Park JY, Eun CS, Han DS, Choi HS. Prevalence of gallstone disease in patients with end-stage renal disease treated with hemodialysis in Korea. Hepato-gastroenterology. 2003;50(54):1792–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gernone G, Detomaso F, La Rosa R, Giannattasio M. [Are dialysis-patients a risk population for cholelithiasis? Study in an apulian population]. Minerva urologica e ne-frologica. Ital J Urol Nephrol. 2009;61(1):21–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badalamenti S, DeFazio C, Castelnovo C, Sangiovanni A, Como G, De Vecchi A. et al. High prevalence of silent gallstone disease in dialysis patients. Nephron. 1994;66(2):225–7. doi: 10.1159/000187805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]