Abstract

Mutations in the gene encoding the lysosomal enzyme glucocerebrosidase, known to cause Gaucher disease (GD), are a risk factor for the development of Parkinson disease (PD) and related disorders. This association is based on the concurrence of parkinsonism and GD, the identification of glucocerebrosidase mutations in cohorts with PD from centers around the world, and neuropathologic findings. The contribution of glucocerebrosidase to the development of parkinsonian pathology was explored by studying seven brain samples from subjects carrying glucocerebrosidase mutations with pathologic diagnoses of PD and/or Lewy body dementia. Three individuals had GD and four were heterozygous for glucocerebrosidase mutations. All cases had no known family history of PD and the mean age of disease onset was 59 years (range 42–77). Immunofluorescence studies on brain tissue samples from patients with parkinsonism associated with glucocerebrosidase mutations showed that glucocerebrosidase was present in 32–90% of Lewy bodies (mean 75%), some ubiquitinated and others non-ubiquitinated. In samples from seven subjects without mutations, <10% of Lewy bodies were glucocerebrosidase positive (mean 4%). This data demonstrates that glucocerebrosidase can be an important component of α-synuclein-positive pathological inclusions. Unraveling the role of mutant glucocerebrosidase in the development of this pathology will further our understanding of the lysosomal pathways that likely contribute to the formation and/or clearance of these protein aggregates.

Keywords: Glucocerebrosidase, α-Synuclein, Parkinsonism, Lewy body dementia

Introduction

Clinical and genetic studies suggest that mutations in the glucocerebrosidase gene (GBA), which encodes the lysosomal enzyme deficient in Gaucher disease (GD), are an important risk factor for the development of parkinsonism. Initially, rare reports described patients with relatively mild GD symptoms, yet progressive parkinsonian manifestations, often associated with cognitive decline [31]. Neuropathologic analyses of brain samples from several subjects with GD and parkinsonism revealed gliosis and Lewy body (LB) pathology, often localized to hippocampal regions CA2-4, areas specifically affected in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) [32]. Family studies revealed that among relatives of Gaucher probands, there was an increased number of individuals affected with parkinsonism [13]. Then, a study of GBA in 57 brain bank samples from subjects with pathologically confirmed PD demonstrated that 12% carried a mutation, which was significantly higher than the mutation frequency even in the at-risk Ashkenazi Jewish population [16]. Subsequently, this finding was confirmed in multiple independent studies in PD cohorts from different ethnicities and a large international collaborative study, including more than 5,000 subjects with PD and the same number of controls, demonstrated that the odds ratio for carrying a GBA mutation was greater than 5, rendering this the most significant genetic risk factor identified to date [1, 4, 18, 26, 28, 33]. Furthermore, GBA mutations have been identified at an increased frequency in subjects with DLB [5, 11].

These clinical, genetic and neuropathologic observations led to an exploration of why GBA mutations constitute a risk factor for the development of parkinsonian manifestations. The role of glucocerebrosidase (GC) in neurodegeneration was explored using brain samples from subjects with LB disorders. We report the presence of GC in LBs and Lewy neurites (LN) in subjects with GBA mutations and propose that the lysosomal enzyme GC, when mutated, may contribute to the aberrant aggregation of α-synuclein, the major component of these inclusions [10, 21, 29].

Methods

Study cases

Brain tissue samples from 15 subjects were obtained from the Massachusetts Alzheimer Disease Research Center (subject 1), the NIH Clinical Center Department of Pathology (cases 2, 3, 12 and 15) and the University of Pennsylvania Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research (subjects 4–11, 13–14). Subject 15 was an 86-year-old patient with GD, but without parkinsonian manifestations. The clinical information, summarized in Table 1, was gathered by reviewing patient charts and/or postmortem pathology reports.

Table 1.

Demographic details, GBA genotype and clinical features of patients studied

| Case | Sex | GBA genotype | Age of onset parkinsonism | Age at death | Clinical diagnosis | Presentation | Cognitive changes | L-Dopa response | Other features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects with GBA mutations | |||||||||

| 1 | F | N370S/unknown | 51 | 62 | GD/PD | Freezing, bradykinesia | Severe dementia | No | Bipolar disorder |

| 2 | M | N370S/N370S | 44 | 54 | GD/PD | Gait instability, tremor | Severe dementia | Yes | Peripheral neuropathy |

| 3 | F | L444P/D409H + dup | 42 | 52 | GD/PD | Tremor, bradykinesia, gait instability | Severe dementia | No | Abnormal vertical and horizontal saccades |

| 4 | M | T267I/WT | 54 | 75 | PD/DLB | Tremor | Severe dementia | Yes | NA |

| 5 | M | N370S/WT | 77 | 89 | PD/AD | Memory problems | Confusion and word retrieval difficulties | NA | NA |

| 6 | M | I161N/WT | 72 | 81 | PD/AD | Shuffling, bradykinesia, cognitive changes | Cognitive decline | Yes | NA |

| 7 | M | R120W/WT | 73 | 79 | PD/DLB | Parkinsonism | Dementia | NA | NA |

| Subjects without GBA mutations | |||||||||

| 8 | M | WT/WT | 56 | 81 | PD | Tremor, gait and balance disturbance | None | Yes | NA |

| 9 | F | WT/WT | 81 | 90 | PD/DLB | Tremor | Dementia | No | NA |

| 10 | F | WT/WT | 60 | 91 | PD | Tremor, bradykinesia | Cognitive decline | Yes | NA |

| 11 | M | WT/WT | 78 | 82 | PD/AD | Cognitive changes, depression | Dementia | Not administered | NA |

| 12 | M | WT/WT | 60 | 91 | PD | Tremor | NA | Yes | NA |

| 13 | F | WT/WT | 60 | 81 | PD/DLB | Tremor | Dementia | No | NA |

| 14 | M | WT/WT | 78 | 82 | PD/AD | Cognitive changes, depression | Dementia | Not administered | NA |

| Subject with Gaucher disease—no parkinsonism | |||||||||

| 15 | M | N370S/N370S | None | 86 | GD | No parkinsonism | None | Not administered | Mesothelioma |

NA not available, unknown second mutation not identified, AD Alzheimer disease, GD Gaucher disease, PD Parkinson disease, DLB dementia with Lewy bodies, dup a previously described recombinant allele where the recombination results in a pseudogene duplication

Mutation detection and Southern blot analyses

High-molecular weight DNA was isolated from brain tissue. Mutations in GBA were determined by direct sequencing of the 11 exons and flanking intronic regions. In patients with a L444P allele, Southern blots were performed on genomic DNA digested with the restriction enzymes SstII, SspI or HincII to search for the presence of a recombinant allele, as described previously [30].

Immunofluorescent staining and confocal microscopy

Immunofluorescence studies on human brain samples were carried out on 7-μm paraffin-embedded, mounted tissue sections from different brain regions, including the hippocampus, substantia nigra, cingulate and frontal cortex. Formalin-fixed tissues were de-paraffinized in xylene for a total of 9 min followed by serial ethanol dehydration. Then, 4% formic acid was applied for 3 min for antigen retrieval. All tissue sections were treated with PBS, 0.3% Triton-X 100 (v/v) (Sigma) and 0.1% BSA (wt/v) (MPI Biochemicals, Solon, OH) to block non-specific reactions. Tissue sections were stained overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies including sheep polyclonal anti-α-synuclein (1:400) (ABR, Rockford, IL), mouse monoclonal anti-α-synuclein (LB 509) (Zymed/Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA), anti-ubiquitin (1:200–1:300) (Zymed/Invitrogen), or anti-LAMP-1 (1:200–1:300) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Three different anti-GC antibodies were used, two commercially available monoclonal anti-mouse anti-glucerebrosidase antibodies (1:100) (Abnova, Taipei, Taiwan and Sigma, St Louis, MO) and rabbit polyclonal anti-GC (R386) (1:400). FITC-, CY3-, CY5- and AMCA-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were applied for 1 h. To quench autofluorescence, Sudan Black staining (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was performed as described [25]. Immunofluorescence detection was performed using a 510 NLO Meta scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany), with a multi-track channel mode to prevent bleed-through, and pinholes were set at 1.12 Airy Units (AU), corresponding to an optical slice of 0.8 μm for both channels. All confocal datasets had a frame size of 512 pixels by 512 pixels, scan zoom of 1 and were line averaged 2–4 times. Images were processed using the Zeiss AIM software version 4.0 sp1 (Carl Zeiss GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). Based on the distribution of LBs in different anatomic regions, α-synuclein pathology was assigned to brainstem (substantia nigra), or limbic (hippocampus and cingulate) regions, or was assessed as “diffuse” when neocortex was involved [15, 17]. The number of α-synuclein-positive LBs was determined by counting the entire tissue sections either from substantia nigra and/or cortex outlined on the slide. GC immunoreactivity was assessed in each LB, using the same datasets, and the results were expressed as the percentage of total number of LBs examined on all sections. To confirm that pathological structures with GC immunoreactivity were true LBs, LBs were marked on some H&E-stained sections, and subsequent immunofluorescent staining and confocal microscopy was performed on the same sections.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Immunohistochemistry was performed on deparaffinized, rehydrated and formic acid-treated sections from substantia nigra using avidin–biotin complex (ABC) detection system (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB). Briefly, after quenching the endogenous peroxidases with 5% hydrogen peroxide in methanol and blocking in 0.1 M Tris with 2% donor horse serum, primary antibodies were applied overnight at 4°C. After washing, sections were sequentially incubated with species-specific, biotinylated secondary antibodies and ABC complex for 1 h each. Bound antibody complexes were visualized by incubating sections in a solution containing 100 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 0.1% Triton-X-100, 1.4 mM DAB, 10 mM imidazole and 8.8 mM hydrogen peroxide [7].

Results

Clinical and genetic features of patients with PD-carrying GBA mutations

Seven patients (5M:2F) carrying GBA mutations and seven without GBA mutations (4M:3F), but with similar neuropathological diagnoses, were studied. The demographics, GBA genotypes and clinical features of each case are summarized in Table 1. Three subjects were homozygous and four were heterozygous for GBA mutations. There was heterogeneity in genotypes. Three subjects carried the common N370S allele, a mutation exclusively associated with type 1 GD, and one each had L444P, D409H, T2671I, R120W and a novel mutation, I161N.

Among subjects carrying GBA mutations, the overall mean age of onset of parkinsonian manifestations was 59 years, ranging from 42 to 77 years. The mean age of onset of parkinsonism was 46 years (42–51) for GBA homozygotes, 69 years (54–77) for heterozygotes, and 72 years (56–81) for patients without GBA mutations. At the time of death, the mean disease duration was 11 years (6–21) in patients with GBA mutations, and 18 years (4–31) in those without mutations. Most had cognitive changes, which were either present at the time of the initial diagnosis or developed during the disease course. Progressive and severe dementia was noted in subjects carrying GBA mutations, especially during the later disease stages.

GC is present in the majority of Lewy bodies in samples from the patients with GBA mutations

The pathologic features of each case are summarized in Table 2. Postmortem pathologic diagnoses encompassed the spectrum of synucleinopathies, including PD and LB dementias (LBD). Some carried the diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies or Alzheimer variant LB dementia. All, but one had advanced LB pathology, consistent with Braak stages V–VI [3]. In case 3, the distribution of LBs was predominantly in the midbrain (Braak stage III). LBD was the most common postmortem diagnoses.

Table 2.

Pathological features of brain samples described in Table 1

| Case | Postmortem diagnosis | α-Synuclein pathologya | Glucocerebrosidase staining Signal intensity and co-localization with α-synuclein |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Synuclein pathologyb | Inclusionsc | |||

| 1 | GD LBD |

Diffuse LB pathology with abundant inclusions in cortex | ++ | + |

| 2 | GD LBD |

Diffuse LB pathology with abundant inclusions in the cortex | ++ | + |

| 3 | GD PD |

LB pathology in brainstem (SN) and sparse LB pathology in limbic (hippocampus) and cortical regions | + | ++ |

| 4 | LBD | Diffuse LB pathology with abundant inclusions and extensive LN in cortex | ++ | + |

| 5 | LBD/AD | Diffuse LB pathology with abundant inclusions in the cortex | + | + |

| 6 | LBD/AD | Diffuse LB pathology with abundant inclusions in the cortex | + | + |

| 7 | LBD/AD | Diffuse LB pathology with abundant inclusions in the cortex | + | ++ |

| Subjects without GBA mutations | ||||

| 8 | PD | Diffuse LB pathology with abundant inclusions in the cortex | <10% show weak puncta-like GC reactivity | ± |

| 9 | LBD | Diffuse LB pathology with abundant inclusions in the cortex | − | ± |

| 10 | LBD | Diffuse LB pathology with abundant inclusions in the cortex | − | ± |

| 11 | LBD | Diffuse LB pathology with abundant inclusions in the cortex | − | ± |

| 12 | PD | Diffuse LB pathology with abundant inclusions in the cortex | − | ± |

| 13 | LBD/AD | LB pathology involving brain stem-SN and limbic regions (hippocampus and cingulate) | − | ± |

| 14 | LBD/AD | Diffuse LB pathology with abundant inclusions in the cortex | ~10% show weak puncta-like GC reactivity | ± |

| Subjects with GD without parkinsonism | ||||

| 15 | GD | No pathology | − | − |

GD Gaucher disease, PD Parkinson disease, LBD Lewy body dementia, LB Lewy body, LN Lewy neurite, GC glucocerebrosidase, AD Alzheimer disease

Assessment of LB pathology based on α-synuclein reactivity: Diffuse pathology indicates involvement brain stem, limbic and neocortical regions [17]

LBs and LNs, displaying GC reactivity

In cases with GBA mutations, GC is visualized in amorphous aggregates; in cases without GBA mutations, GC displays a weak, puncta-like signal

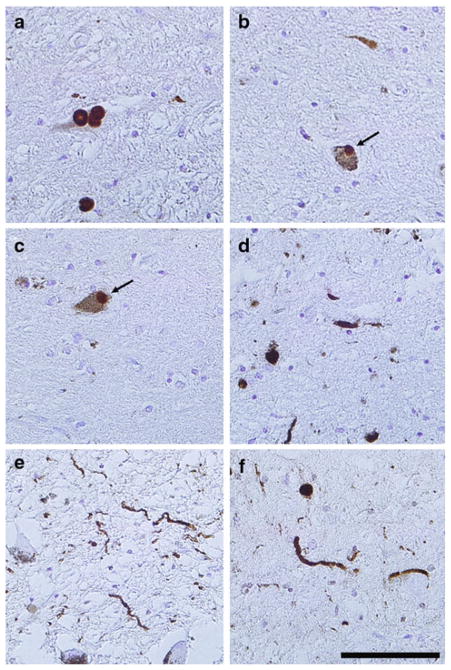

Immunohistochemical analysis of substantia nigra from subjects with GBA mutations demonstrated that the LB pathology observed was also recognized with anti-glucocerebrosidase antibody. Figure 1 shows LBs and LNs in these samples staining positive for both α-synuclein and glucocerebrosidase.

Fig. 1.

Lewy pathology in the substantia nigra of patients with GBA mutations as demonstrated by immunohistochemistry using anti-glucocerebrosidase antibodies. Paraffin-embedded brain sections from substantia nigra stained with anti-α-synuclein antibody (Syn 505) (a, d) or anti-GC antibody (b, c, e, f) in case 7 (a–c), case 5 (d, e) and case 4 (f). Antibodies against α-synuclein depicted typical staining of Lewy bodies (a) and Lewy neurites (d). In cases with GBA mutations, anti-GC antibody recognized both Lewy bodies (b, c) and Lewy neurites (e, f). Tissue sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Scale bar 100 μm

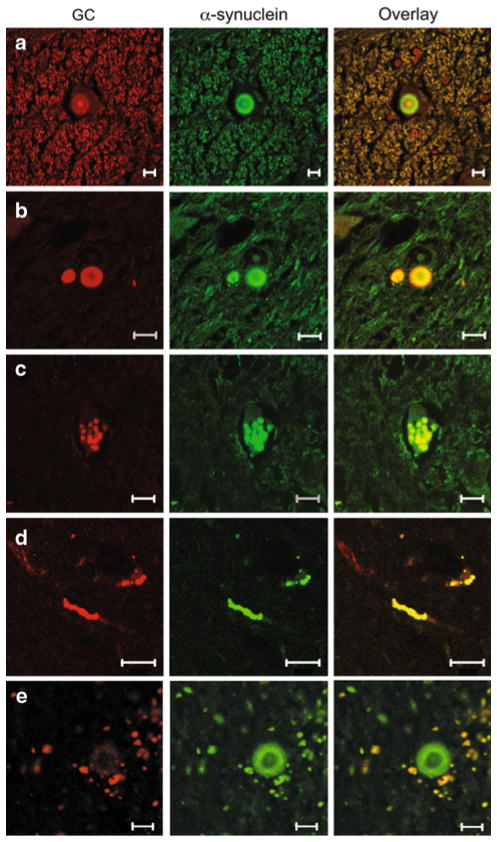

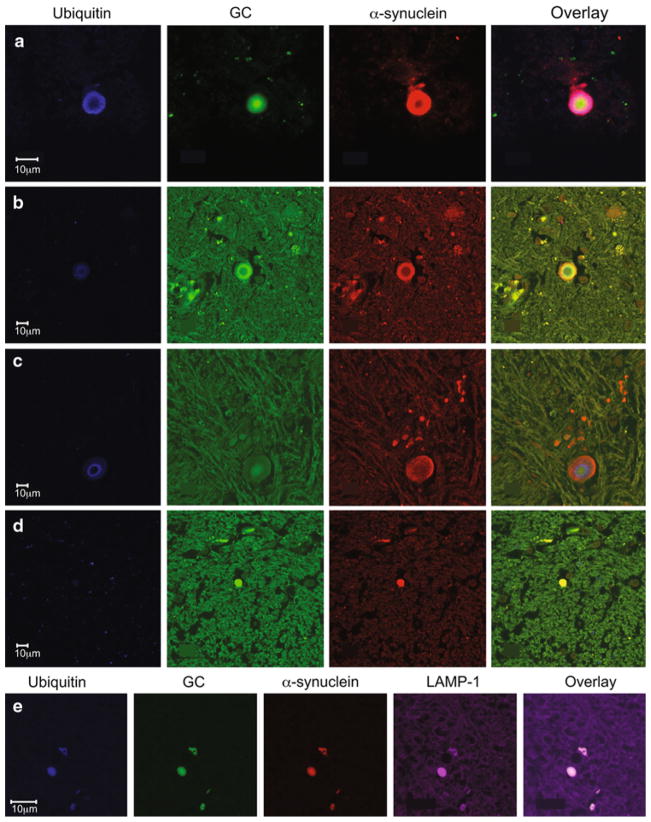

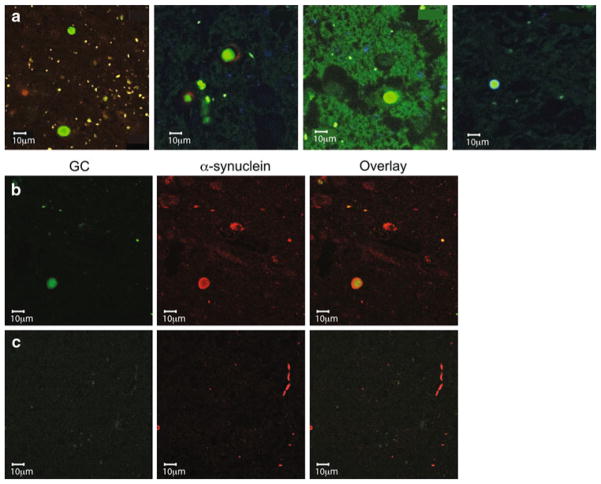

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy studies using different antibodies against GC and α-synuclein demonstrated that GC was present in a similar pattern in LBs and LNs in patients with at least one GBA mutation (Figs. 2, 3). In brainstem type LBs, GC was mostly found in the LB core, while in cortical LBs, it is co-localized more uniformly with α-synuclein. GC was present in both ubiquitinated and non-ubiquitinated LBs, but also co-localized with the lysosomal marker, LAMP-1 (Fig. 3). These positive inclusions persisted after quenching with Sudan Black (Supplemental Figure S1 and S2). In contrast, in patients without GBA mutations, <10% of the LBs showed a weak signal for GC (Figs. 2e, 4a). LNs stained strongly for GC in samples from patients with GBA mutations (Fig. 2d), but not in those without GBA mutations (Fig. 4c). However, GC staining was observed in some diffuse amorphous α-synuclein aggregates in subjects without GBA mutations (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 2.

Glucocerebrosidase is present in LBs and LNs in subjects carrying GBA mutations. Double-label immunofluorescence showing GC (red) and α-synuclein (green) in LBs from a case 1, b case 2. GC co-localized with α-synuclein in amorphous inclusions (c) in case 3. d In brain samples from case 4, genotype T267I/WT, both LBs and LNs showed similar GC immunoreactivity. GC and α-synuclein co-localized as shown in the overlay panels. e Paucity of GC staining in LBs in a case with LBD (case 11) without GBA mutations. Scale bar 10 μm

Fig. 3.

Glucocerebrosidase is in both ubiquitinated and non-ubiquitinated LBs, and co-localizes with the lysosomal marker, LAMP-1. Representative co-staining of LBs in samples from two subjects (cases 1 and 2) with synucleinopathies and GBA mutations [α-synuclein red, GC green, ubiquitin blue, LAMP-1 purple). In brainstem type LBs, there was immunoreactivity to α-synuclein in the peripheral rim, while GC was present either at the outer ring (b) or central core (a, c) in ubiquinated LBs]. In cortical LBs, GC co-localized with α-synuclein (d). In some LBs that co-stained for GC and α-synuclein, there was no ubiquitin reactivity (d). e Staining with α-synuclein, GC, ubiquitin and the lysosomal marker, LAMP-1 in the same sections (case 5). Overlay shows co-localization of all four markers in a LB

Fig. 4.

LBs, LNs and perikaryal neuronal inclusions in samples from subjects with synucleinopathies without GBA mutations. a LBs staining for α-synuclein (green), but not GC (red) in samples from four different patients without GBA mutations (cases 8–11). b In some subjects without GBA mutations (case 8 shown) occasional LBs display GC reactivity (green), whereas LNs (c) do not show GC reactivity

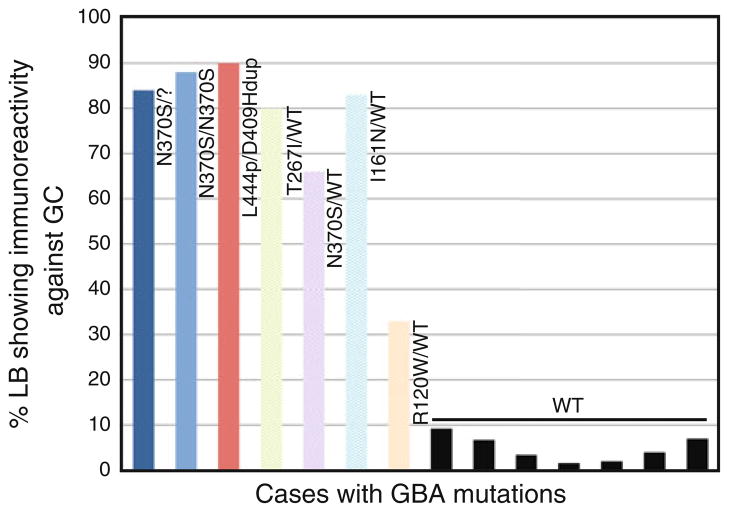

In samples from GBA homozygotes, quantification of GC-positive LBs demonstrated that more than 80% were positive for GC, while GC immunoreactivity ranged from 90 to 33% in heterozygotes with a mean of 75% (Fig. 5). The distribution of GC-positive LBs correlated with the neuropathologic diagnosis, and there was no predilection for a specific anatomical site in the brain. The number of ubiquitinated LBs in two subjects was quantified by assessing ubiquitin immunoreactivity after counting all GC-positive LBs. In case 1, a subject homozygous for GBA mutations, 30% of GC-positive LBs were ubiquitinated, and in case 5, a heterozygote, 20% were ubiquitinated. Among the subjects without GBA mutations, the mean number of LBs that showed GC immunoreactivity was 5%.

Fig. 5.

Fraction of LBs staining positive for glucocerebrosidase. Glucocerebrosidase-positive LB load in brain samples, expressed as percentage of total LBs counted over the entire sections. Colored bars represent the GC immunoreactive LBs in samples from cases with Gaucher disease; pastel-colored bars represent LBs in GBA heterozygotes and solid black bars indicate the LBs from cases without GBA mutations

An autopsy sample from an 86-year-old patient with type 1 GD without any clinical manifestations of parkinsonism was also evaluated (case 15). Neuropathology and immunofluorescence studies failed to detect any LB pathology.

Discussion

Mutations in glucocerebrosidase have been reported with an increased frequency among subjects with LB disorders, especially in cases characterized by extensive cortical involvement [19]. PD and other adult-onset neurodegenerative disorders share a common pathology, characterized by the aberrant accumulation of proteins in the brain, associated with neuronal cell death. In this study, we explored whether mutant GC might be involved in the process of α-synuclein inclusion formation in patients with GBA mutations. Initially, the discovery of α-synuclein mutations in rare families with early onset PD led to an appreciation that α-synuclein was a major element of LB pathology in brain samples from subjects with sporadic PD [2, 23]. The demonstration of GC in LBs and LNs in brain samples from subjects carrying GBA mutations similarly supports a role for mutant GC in LB biogenesis in vivo. The presence of GC in LBs and LNs in patients with GBA mutations indicates that mutant GC may directly or indirectly induce α-synuclein aggregation through a gain of function mechanism. The high percentage of LBs staining positive for GC, regardless of the antibody used, supports an active role for this protein in LB formation and renders passive entrapment less likely. Although GC appears to be associated with α-synuclein pathology in each case with parkinsonism and GD, the formation and distribution of GC-positive LBs was less uniform among GBA heterozygotes. This finding suggests that the contribution of GC to the process of LB formation might be enhanced by other stressors, such as mitochondrial damage, aging or environmental exposures. In addition, because most GBA mutation carriers, even homozygotes, do not develop parkinsonism, the impact of GBA mutations may be additive, rather than serving as a single risk factor.

Abnormal proteins can be targeted for degradation by ubiquitination, and ubiquitin reactivity can be a marker of the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) activation [27]. Although the GC reactivity of LBs might merely reflect the presence of misfolded GC destined for UPS degradation, this seems unlikely since we found GC in both ubiquitinated and non-ubiquitinated LBs in brain samples from different subjects with synucleinopathies (Fig. 3).

Interestingly, the GC-positive aggregates stained with the lysosomal marker, LAMP-1 (Fig. 3e). There is considerable evidence implicating defects in the lysosome–autophagy pathway in neurodegenerative disorders. Furthermore, α-synuclein can be selectively translocated into the lysosomes for degradation by chaperone-mediated autophagy and aggregated forms of α-synuclein may be degraded by lysosomes [6]. It is possible that mutant GC may contribute to impaired α-synuclein clearance in the lysosome, and thus may enhance the formation of the α-synuclein inclusions.

Like GC, lipids are located in the core of brain stem-type LBs and are observed diffusely in cortical LBs [8], and hence, abnormal lipid deposition could also play a role in GBA-associated parkinsonism. In the cytosol, α-synuclein is associated with lipid rafts and caveolae. The A30P α-synuclein mutation, disrupts this interaction, and α-synuclein is redistributed away from the synaptic compartment [24]. The lipid composition of rafts was shown to be altered in a cell-based GD model, and such alterations may similarly disrupt the association of α-synuclein with lipid microdomains [14]. This suggests that impaired lysosomal function or a focal decrease in GC activity resulting from these mutations could play a key role in the pathogenesis of different synucleinopathies.

This study of seven brain samples from patients with GBA mutations with clinical manifestations of parkinsonism revealed pathologic changes within the spectrum of classical PD. However, most also had abundant limbic or diffuse neocortical Lewy pathology. Subjects had a range of parkinsonian manifestations, with variations in the age of onset, progression of disease, L-dopa responsiveness, and the extent of cognitive changes as previously described [12]. Several genetic studies have reported that the age at disease onset in patients with GBA mutations is on an average 1.7–6.0 years earlier than in those without mutations [9, 20]. This finding was supported by the current study, and the mean age of disease onset in the homozygotes studied was 23 years earlier than that among the heterozygotes.

Most recessively inherited Mendelian disorders are caused by the loss of function of a specific protein. Heterozygotes with a single wild-type allele produce adequate amounts of the normal protein and are generally asymptomatic. In homozygotes with GD, a “simple” Mendelian disorder, GBA mutations result in the deficiency of the membrane-associated lysosomal enzyme GC, leading to the accumulation of the lipid substrate glucocerebroside in macrophages of the reticuloendothelial system. In Gaucher carriers, the residual enzymatic activity varies considerably, with levels ranging from<50%, to within the normal range, and the abnormal lipid does not accumulate. In patients with GD, Gaucher cells, lipid-laden macrophages, are observed in many organs, including liver, spleen and bone marrow, and the disease manifests with organomegaly, anemia, thrombocytopenia and skeletal involvement and with CNS involvement in neuronopathic GD (types 2 and 3). Although occasional peri-vascular Gaucher cells are seen, abnormal lipid storage in the brain does not adequately account for the neurological symptoms in neuronopathic GD. While a toxic alternate substrate of GC, glucosylsphingosine accumulates in the brain in types 2 and 3 GD, glucosylsphingosine was not detected in brain samples from subjects with PD and GD [16, 22]. The finding of parkinsonism in subjects with type 1 GD, and in Gaucher carriers, indicates that the pathogenic mechanism is either different or additive to the loss of enzymatic function.

In conclusion, this study provides further evidence that mutations in GBA contribute to α-synuclein pathology. When mutated, GC, a lysosomal house-keeping protein critical in a rare Mendelian disorder, likely acquires a different function contributing to the development of PD, a seemingly unrelated common complex disorder. Further studies will be needed to better elucidate the mechanisms linking mutant GC to the formation of α-synuclein aggregates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephen Wincovitch for technical assistance with confocal microscopy, and Julia Fekecs and Jae Choi for preparation of the figures. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute and Udall Centre of Excellence in Parkinson’s Disease Research Grant (NS053488).

Footnotes

In memoriam: With love and gratitude, we remember Mary E. LaMarca, who contributed to this work by sharing her ideas, offering constructive criticism and assisting in the preparation of the figures.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00401-010-0741-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Conflict of interest The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Ozlem Goker-Alpan, Section on Molecular Neurogenetics, Medical Genetics Branch, NHGRI, National Institutes of Health, Building 35, Room 1A213, 35 Convent Drive, MSC 3708, Bethesda, MD 20892-3708, USA.

Barbara K. Stubblefield, Section on Molecular Neurogenetics, Medical Genetics Branch, NHGRI, National Institutes of Health, Building 35, Room 1A213, 35 Convent Drive, MSC 3708, Bethesda, MD 20892-3708, USA

Benoit I. Giasson, Department of Pharmacology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA

Ellen Sidransky, Email: sidranse@mail.nih.gov, Section on Molecular Neurogenetics, Medical Genetics Branch, NHGRI, National Institutes of Health, Building 35, Room 1A213, 35 Convent Drive, MSC 3708, Bethesda, MD 20892-3708, USA.

References

- 1.Aharon-Peretz J, Rosenbaum H, Gershoni-Baruch R. Mutations in the glucocerebrosidase gene and Parkinson’s disease in Ashkenazi Jews. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1972–1977. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba M, Nakajo S, Tu PH, et al. Aggregation of alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies of sporadic Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:879–884. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rub U, et al. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bras J, Paisan-Ruiz C, Guerreiro R, et al. Complete screening for glucocerebrosidase mutations in Parkinson disease patients from Portugal. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30:1515–1517. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark LN, Kartsaklis LA, Wolf Gilbert R, et al. Association of glucocerebrosidase mutations with dementia with Lewy bodies. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:578–583. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuervo AM, Stefanis L, Fredenburg R, Lansbury PT, Sulzer D. Impaired degradation of mutant alpha-synuclein by chaperone-mediated autophagy. Science. 2004;305:1292–1295. doi: 10.1126/science.1101738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duda JE, Giasson BI, Gur TL, et al. Immunohistochemical and biochemical studies demonstrate a distinct profile of α-synuclein permutations in multiple system atrophy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:830–841. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.9.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gai WP, Yuan HX, Li XQ, et al. In situ and in vitro study of colocalization and segregation of alpha-synuclein, ubiquitin, and lipids in Lewy bodies. Exp Neurol. 2000;166:324–333. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gan-Or Z, Giladi N, Rozovski U, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations between GBA mutations and Parkinson disease risk and onset. Neurology. 2008;70:2277–2283. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304039.11891.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:492–501. doi: 10.1038/35081564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goker-Alpan O, Giasson BI, Eblan MJ, et al. Glucocerebrosidase mutations are an important risk factor for Lewy body disorders. Neurology. 2006;67:908–910. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000230215.41296.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goker-Alpan O, Lopez G, Vithayathil J, et al. The spectrum of parkinsonian manifestations associated with glucocerebrosidase mutations. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1353–1357. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.10.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goker-Alpan O, Schiffmann R, LaMarca ME, et al. Parkinsonism among Gaucher disease carriers. J Med Genet. 2004;41:937–940. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.024455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hein LK, Duplock S, Hopwood JJ, Fuller M. Lipid composition of microdomains is altered in a cell model of Gaucher disease. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:1725–1734. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800092-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, Lees AJ. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinicopathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55:181–184. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.3.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lwin A, Orvisky E, Goker-Alpan O, LaMarca ME, Sidransky E. Glucocerebrosidase mutations in subjects with parkinsonism. Mol Genet Metab. 2004;81:70–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65:1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitsui J, Mizuta I, Toyoda A, et al. Mutations for Gaucher disease confer high susceptibility to Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:571–576. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neumann J, Bras J, Deas E, et al. Glucocerebrosidase mutations in clinical and pathologically proven Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2009;132:1783–1794. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nichols WC, Pankratz N, Marek DK, et al. Mutations in GBA are associated with familial Parkinson disease susceptibility and age at onset. Neurology. 2009;72:310–316. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327823.81237.d1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norris EH, Giasson BI, Lee VM. Alpha-synuclein: normal function and role in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2004;60:17–54. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(04)60002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orvisky E, Park JK, LaMarca ME, et al. Glucosylsphingosine accumulation in tissues from patients with Gaucher disease: correlation with phenotype and genotype. Mol Genet Metab. 2002;76:262–270. doi: 10.1016/s1096-7192(02)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polymeropoulos MH, Lavedan C, Leroy E, et al. Mutation in the alpha-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson’s disease. Science. 1997;276:2045–2047. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramakrishnan M, Jensen PH, Marsh D. Association of alpha-synuclein and mutants with lipid membranes: spin-label ESR and polarized IR. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3386–3395. doi: 10.1021/bi052344d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romijn HJ, van Uum JF, Breedijk I, et al. Double immunolabeling of neuropeptides in the human hypothalamus as analyzed by confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscopy. J Histochem Cytochem. 1999;47:229–236. doi: 10.1177/002215549904700211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato C, Morgan A, Lang AE, et al. Analysis of the glucocerebrosidase gene in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2005;20:367–370. doi: 10.1002/mds.20319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shults CW. Lewy bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1661–1668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509567103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sidransky E, Nalls MA, Aasly JO, et al. Multicenter analysis of glucocerebrosidase mutations in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1651–1661. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, et al. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388:839–840. doi: 10.1038/42166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tayebi N, Reissner KJ, Lau EK, et al. Genotypic heterogeneity and phenotypic variation among patients with type 2 Gaucher’s disease. Pediatr Res. 1998;43:571–578. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199805000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tayebi N, Walker J, Stubblefield B, et al. Gaucher disease with parkinsonian manifestations: does glucocerebrosidase deficiency contribute to a vulnerability to parkinsonism? Mol Genet Metab. 2003;79:104–109. doi: 10.1016/s1096-7192(03)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong K, Sidransky E, Verma A, et al. Neuropathology provides clues to the pathophysiology of Gaucher disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2004;82:192–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ziegler SG, Eblan MJ, Gutti U, et al. Glucocerebrosidase mutations in Chinese subjects from Taiwan with sporadic Parkinson disease. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;91:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.