Abstract

Widespread invasion by Bromus tectorum (cheatgrass) in the Intermountain West has drastically altered native plant communities. We investigated whether Elymus multisetus (big squirreltail) is evolving in response to invasion and what traits contribute to increased performance. Seedlings from invaded areas exhibited significantly greater tolerance to B. tectorum competition and a greater ability to suppress B. tectorum biomass than seedlings from adjacent uninvaded areas. To identify potentially adaptive traits, we examined which phenological and phenotypic traits were correlated with seedling performance within the uninvaded area, determined their genetic variation by measuring sibling resemblance, and asked whether trait distribution had shifted in invaded areas. Increased tolerance to competition was correlated with early seedling root to shoot ratio, root fork number, and fine root length. Root forks differed among families, but none of these traits differed significantly across invasion status. Additionally, we surveyed more broadly for traits that varied between invaded and uninvaded areas. Elymus multisetus plants collected from invaded areas were smaller, allocated more biomass to roots, and produced a higher percentage of fine roots than plants from uninvaded areas. The ability of native populations to evolve in response to invasion has significant implications for the management and restoration of B. tectorum-invaded communities.

Keywords: adaptation, competition, contemporary evolution, ecological genetics, invasive species, natural selection, restoration

Introduction

The impact of invasive species on native species, communities, and ecosystem processes has been recognized for decades (Elton 1958; Lodge 1993). Biologic invasions dramatically affect the distribution, abundance, and fitness of many native species (Williamson 1996; Mack et al. 2000). While biologic invasions are considered a significant threat to biodiversity (Sala et al. 2000; Stein et al. 2000), they do not result in the extinction of all native species impacted; many native species are able to persist alongside invaders (Hironaka and Tisdale 1963; Levine and Rees 2004; Mealor et al. 2004; Stohlgren et al. 2006). These persistent native species may possess traits (i.e. preadaptations) or sufficient phenotypic plasticity that allows for successful coexistence with invaders (MacNeil et al. 2001; Carroll et al. 2005). Preadapted traits can increase in frequency in invaded populations, or under the right circumstances, native species may evolve new mechanisms, such as chemical defenses or improved competitive ability, to cope with the invaders. Both types of rapid evolutionary responses have been documented in native populations (Schlaepfer et al. 2005; Strauss et al. 2006). Most research involving rapid evolution in native species responding to invaders has focused on native–invader interactions across trophic levels (e.g. predator–prey, host–pathogen relationships, Strauss et al. 2006). To date, there are fewer studies that address evolutionary response of native plant populations to plant invaders (e.g. Callaway et al. 2005; Lau 2006; Mealor and Hild 2007; Cipollini and Hurley 2008; Leger 2008; Ferrero-Serrano et al. 2010), but all have found evidence that some native plants can evolve in response to invasive competitors. The experiment presented here differs from previous ones in that, in addition to determining whether native populations have evolved increased ability to compete with invaders, we also identify particular traits that are evolving, as well as determine the amount of genetic variation within populations for adaptive morphological and phenological traits.

The conversion of Great Basin rangeland to Bromus tectorum L. (cheatgrass) is one of the most severe ecological degradations in the United States (Mack 1981; D'Antonio and Vitousek 1992). A combination of heavy grazing, which reduces the vigor of native perennial species, and B. tectorum invasion, which shortens fire return interval and alters nutrient cycling, has resulted in large-scale conversion of Artemisia spp. (sagebrush)-dominated plant communities to B. tectorum-dominated communities (Young et al. 1972; Evans et al. 2001; Brooks et al. 2004; Chambers et al. 2007). By 2000, nearly 12.7 million hectares of the Great Basin had been converted to B. tectorum and 45% was estimated to be at risk of conversion (Menakis et al. 2003; Bradley and Mustard 2005).

Bromus tectorum has strong negative impacts on native perennial plant fitness (Aguirre and Johnson 1991; Nasri and Doescher 1995; Rafferty and Young 2002; Humphrey and Schupp 2004). A few native grass species appear to be relatively tolerant of B. tectorum invasion, including the closely related E. multisetus M.E. Jones (big squirreltail) and Elymus elymoides Raf. (Swezey) (bottlebrush squirreltail) (Hironaka and Tisdale 1963; Booth et al. 2003; Leger 2008). Both are highly selfing, short-lived perennials that reproduce effectively from seed, persist in disturbed areas, and survive moderate fires, with gene flow occurring primarily through wind-dispersed seeds (Young and Evans 1977; Britton et al. 1990; Jones 1998; Larson et al. 2003). A tolerance for disturbance has made both squirreltail species of interest for the restoration of burned and B. tectorum-invaded areas (Jones 1998; Richards et al. 1998; Humphrey and Schupp 2002). Direct comparison between squirreltail and annual grass competitors in relative growth rate (Hironaka and Sindelar 1975; Arredondo et al. 1998), productivity under both low and high N availability (James 2008), and germination percentage and phenology (Young et al. 2003) usually favor the invader, suggesting that no individual strategy can account for squirreltail's tolerance of invasion.

Increased ability to tolerate B. tectorum competition has been demonstrated in mature E. multisetus plants collected from B. tectorum-invaded areas (Leger 2008), but shifts in seedling performance have not been investigated. The transition from seed to seedling is the most vulnerable stage of plant life (Kitajima 2007) and is crucial for a successful restoration from seed; examination of seedling performance is an important measure for estimating fitness differences between plants. Any trait with inherited phenotypic variation that increases seedling establishment in B. tectorum-invaded areas would likely be favored by natural selection and increase in frequency over time in invaded populations. Measuring the performance of seeds from the same plant (i.e. siblings) can provide an estimate of genetic variation in particular traits. Family-level analysis has been used for decades to address the questions of inheritance and natural selection (Endler 1986; Falconer and MacKay 1996) but is not frequently applied in the context of native plant restoration.

The goals of this study are twofold: (i) to test whether seedlings of E. multisetus plants collected from invaded areas are more successful when grown with B. tectorum than seedlings from nearby uninvaded areas and (ii) to identify what growth traits may help E. multisetus seedlings to establish in B. tectorum-invaded areas. We conducted a common garden greenhouse experiment with maternal families collected from invaded and uninvaded areas with known differences in adult competitive ability (Leger 2008), and we measured E. multisetus seedling performance and B. tectorum biomass production. Two methodologies were used to identify potentially important traits. First, we identified traits that were correlated with increased tolerance of B. tectorum competition in seedlings, quantified genetic variation of these traits, and asked whether adaptive traits have shifted between uninvaded and invaded populations. If populations are evolving in response to B. tectorum pressure and if traits correlated with performance in the greenhouse are also important in the field, we would expect to see an increased frequency of inherited performance-related traits within invaded areas. Secondly, we surveyed all growth traits that varied in frequency between uninvaded and invaded populations, casting a wider net to identify additional traits that may confer a competitive advantage to native plants growing in invaded areas.

Materials and methods

Seed collection methods

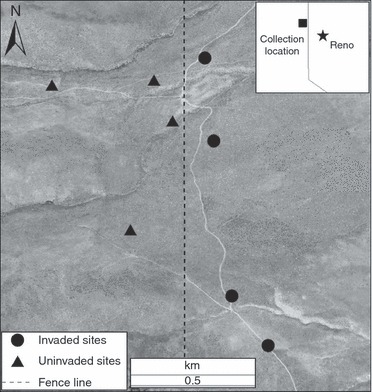

Seeds of E. multisetus were collected in June 2007 from a sagebrush steppe plant community in Balls Canyon, Sierra County, California (Fig. 1.; 139840.740 N, 120803.360 W, 1600 m elevation), where a shift in invasion status occurs over a relatively small geographic area (ranging from 0%B. tectorum in uninvaded areas to 40%B. tectorum cover in invaded areas). Detailed description of community composition of the collection area is recorded in Leger (2008). At the time of seed collection, B. tectorum invasion at this site followed fence line boundaries, with B. tectorum occurring in an area that has received a longer annual season of higher intensity grazing than uninvaded areas for ∼100 years (C. Ross, personal communication). To ensure that the greatest differences between collections were disturbance history and current B. tectorum cover, rather than other abiotic conditions, all collection sites were located within 1.2 km of each other (Fig. 1). However, there are uncontrolled environmental differences between invaded and uninvaded collection sites, namely elevation and soil type. At Balls Canyon, invaded seed collection sites are, on average, 36 m lower than uninvaded areas. Higher elevation sites also exhibit different soil types than lower elevation sites; while all series are well drained and exhibit the same bedrock, the soils at higher elevation collection sites contain a higher percentage of coarse material (>2 mm) (NRCS 2008). A portion of the study area burned in 2006, and the remainder burned in 2007, and currently, the density and cover of B. tectorum in uninvaded areas sampled for this study has increased (E. Leger, personal observation), indicating that the lack of invasion in the higher elevation sites was probably due to differences in disturbance history, rather than lack of suitable environmental conditions for invasion.

Figure 1.

Study location in Balls Canyon, Sierra County, California, with invaded and uninvaded areas in close proximity. The fence line (visible from aerial photos, but marked here for emphasis) represents a management boundary separating invaded areas (east) from uninvaded areas (west).

Seeds were collected from individual E. multisetus plants from four invaded and uninvaded sites (Fig. 1) and stored at room temperature. All seeds collected from an individual represent a maternal family line, and a ‘family’ refers to seeds collected from an individual plant in the field. Twenty-five families were randomly selected from the available pool of seeds from invaded and uninvaded sites (50 families total). Depending on seed availability, 18–20 seeds from each family were used for this experiment (991 plants total). For brevity, families and seedlings produced from seeds collected in invaded sites are subsequently referred to as ‘invaded families’ and ‘invaded plants’ and families and seedlings produced from seeds collected at uninvaded sites, ‘uninvaded families’ and ‘uninvaded plants.’ Seeds of B. tectorum were bulk-collected from the invaded portion of the study area in June 2007.

Greenhouse and data collection methods

The experiment was conducted under controlled greenhouse conditions: 4.4–26.6°C temperature range; 5–25% relative humidity; full daytime sunlight. Potting mix was locally produced (R.C. Donovan, Reno, NV) and contained bark, compost, decomposed granite, and perlite. Laboratory tests of the potting mix revealed very low mineral N (3 ppm), high alkalinity (pH = 8.0), and low estimated water holding capacity (44%) (A and L Western Agricultural Laboratories Report #08-136-060 2008). To allow for maximum rooting depth, we used pots designed for revegetation horticulture (Stuewe and Sons TPOT1; 10.2 × 10.2 × 35.6 cm; 3.2 L). Seeds received no pregermination treatment, and one individually weighed E. multisetus seed was directly sown into each pot on 26 March 2008. To create competitive conditions, we sowed five B. tectorum seeds into each of 14–16 pots for each squirreltail family (n = 791). This density was chosen to produce a competitive environment but was lower than field densities to facilitate root harvests (described elsewhere). An additional four pots per family were established as noncompeting controls (n = 200). Pots for the same family were sown together and then moved into randomly assigned positions to achieve a complete random design. We misted the soil surface immediately after sowing and continued misting twice daily for 2 weeks. For the remainder of the experiment, plants were hand-watered to saturation when the bottom third of root zone was dry (4- to 14-day intervals), which maintained relatively droughty conditions, and no supplemental fertilizer was added.

We measured or calculated a total of 47 growth traits including above-ground and below-ground measures (root methods are described in detail below): seed weight; emergence date; early growth rate (leaf number and length); root, shoot, and total biomass weight (mg) at 10, 50, and 100 days; leaf number and root to shoot ratio (R:S) at 10, 50, and 100 days; total root length (cm), root diameter (mm), number of root tips, number of root forks, and root length in five 0.1 mm size classes at 10, 50, and 100 days after peak germination. Three sequential harvests were conducted on seedlings grown in competition with B. tectorum. Harvest dates were selected to correspond to important phenological benchmarks, including seedling establishment phase (10 days after peak germination), the active growth phase (50 days), and the end of growing season (100 days). Plants for harvest were randomly selected within families. Two plants per family (n = 100) were harvested at 10 days after peak germination, (14–16 April 2008), and three plants per family (n = 150) were harvested at 50 days (16–18 May 2008). At 100 days, owing to the time requirements for root harvest, we were only able to harvest one competing and one noncompeting plant per family (n = 100, 15–18 July 2008). At 100 days, leaf number was recorded for all live plants (n = 669). Plant traits were deliberately measured at a common time, rather than at a particular age/size class, to measure E. multisetus performance relative to B. tectorum in a realistic seedling competition scenario (B. tectorum seeds typically emerge within 24–36 h of planting, which was the case in this experiment as well). Thus, differences between plants harvested on the same date may reflect patterns determined by ontology of trait development (e.g. Fransen et al. 1999; Aanderud et al. 2003) as well as fixed differences in traits.

Emergence began on 1 April 2008 and was recorded daily until last recorded emergence on 15 April 2008. By 4 April 2008, 820 of 921 seeds had emerged, which represented over 90% of all emergents, and all seedling ages are displayed from 4 April, representing the end of peak germination. For a subset of 406 seedlings, leaf length and number were measured on 23 April and 15 May 2008. Early seedling growth rate was quantified as [May leaf number−April leaf number]/May leaf number. To extract roots at harvest, we cut away pots and gently removed planting media by misting with water. Elymus multisetus were identified by leaf and root characteristics and manually separated from B. tectorum roots. Harvested roots and shoots were refrigerated (<48 h) and then digitally scanned for analysis using WinRhizo software (Regent Instruments Inc, Saint-Foy, QC). WinRhizo was utilized to quantify the following root characteristics: total root length (cm), root diameter (mm), number of root tips and root forks (measurements of root branching), and root length (cm) in five 0.1-mm-diameter size classes. Root and shoot biomass measurements were taken by drying (7 days at 60°C) and weighing root and shoot biomass separately. Total biomass was calculated as shoot + root weight. No plants produced seeds in the first year of growth, and not all families produced seeds under competition in the second year of growth, so common-garden-produced seed was collected and weighed from a subset of noncompeting control plants from each family that were maintained through July 2009.

Relative competitive performance index (CPI) was used to quantify seedling tolerance to B. tectorum competitors (Keddy et al. 1998). CPI is the percent decrease in plant performance when grown with competitors and was calculated as: [Leaf number without competition−leaf number with competition]/leaf number without competition. Leaf number is strongly correlated with plant biomass in E. multisetus (presented in results) and was used as a proxy for plant size in CPI calculation. We calculated family means for leaf number with and without competition, and these mean values were used for CPI calculation. To quantify B. tectorum suppression, above-ground biomass was collected from all pots containing B. tectorum (n = 507) at 100 days. In 32 competition pots, there was no E. multisetus emergent, but four or more B. tectorum emergents. Elymus multisetus seeds that failed to emerge were significantly smaller than seeds that did emerge (presented in results), indicating that failure of E. multisetus emergence in some pots was likely related to seed factors, rather than to soil characteristics or pot placement. Pots without E. multisetus seedlings were used to calculate mean B. tectorum weight grown alone, and B. tectorum shoots were dried and weighed in same manner as E. multisetus.

Analysis methods

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP 7.0.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the effects of invasion status and family on 47 growth traits of E. multisetus seedlings in competition. For seed weight, emergence date, early growth rates, 10-day harvest data, 50-day harvest data, 100-day leaf number, and next-generation seed weight, the ANOVA model included the following factors: invasion status (invaded or uninvaded); collection site (random factor, nested in status); family (random factor, nested in status and site). Family was removed from ANOVA models for the analysis of 100-day biomass and 100-day root traits, because only one plant per family was measured in each competition condition, as well as from ANOVA of CPI, because they were calculated using family means. Seed weight and emergence date comparisons included all data, rather than just competing plants, because these traits were not affected by competition condition. For B. tectorum biomass, two separate ANOVAs were conducted to analyze the effect of three levels of competition condition (grown alone, or grown with invaded/uninvaded E. multisetus) and the family of E. multisetus competitor. For this second analysis of B. tectorum biomass, E. multisetus family was nested within collection site. When analyses were significant, means were compared a posteriori using Tukey Honestly significant difference (HSD). Several growth traits were log-transformed to improve fit to assumptions of ANOVA (indicated in Table 1). Raw means and standard errors, rather than transformed values or least means square, are reported for all growth trait and competitive ability measurements. Spearman's ρ was used to determine nonparametric correlations between family mean CPI and family means for each growth trait among uninvaded families. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons in these analyses because the goal of these experiments was to maximize the chances of identifying potentially important traits, which can serve as the foundation for additional follow-up testing in this and other native perennial grass species.

Table 1.

Traits of Elymus multisetus grown in competition with Bromus tectorum that varied significantly by invasion status, family, or both

| Status | Site | Family | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response variable | n | r2 | F | P | F | P | F | P |

| Early traits | ||||||||

| Seed weight (g) | 991 | 0.44 | 69.77 | <0.0001 | 7.72 | <0.0001 | 14.14 | <0.0001 |

| Emergence date | 950 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.7799 | 1.98 | 0.0664 | 1.86 | 0.0009 |

| Early growth rate (leaf no.) | 402 | 0.47 | 33.93 | <0.0001 | 23.17 | <0.0001 | 3.04 | <0.0001 |

| Early growth rate (leaf length) | 402 | 0.29 | 11.91 | 0.0006 | 10.58 | <0.0001 | 1.69 | 0.0065 |

| 10-day traits | ||||||||

| 10-day total weight (mg) | 99 | 0.62 | 0.01 | 0.9324 | 2.38 | 0.0425 | 1.58 | 0.061 |

| 10-day (0.201–0.3 mm)* | 99 | 0.69 | 0.89 | 0.3495 | 6.33 | <0.0001 | 1.72 | 0.0346 |

| 50-day traits | ||||||||

| 50-day total weight (mg) | 147 | 0.61 | 7.09 | 0.0091 | 10.35 | <0.0001 | 1.97 | 0.0033 |

| 50-day shoot weight (mg)* | 148 | 0.66 | 5.22 | 0.0245 | 16.10 | <0.0001 | 2.20 | 0.0007 |

| 50-day root weight (mg)* | 148 | 0.57 | 0.76 | 0.3840 | 10.04 | <0.0001 | 1.73 | 0.0138 |

| 50-day R:S | 147 | 0.50 | 6.40 | 0.0130 | 5.74 | <0.0001 | 1.39 | 0.0953 |

| 50-day leaf no. | 148 | 0.66 | 8.42 | 0.0046 | 12.45 | <0.0001 | 2.48 | 0.0001 |

| 50-day root total root length (cm)* | 145 | 0.53 | 0.11 | 0.7349 | 4.21 | 0.0008 | 2.02 | 0.0026 |

| 50-day root tips* | 145 | 0.50 | 2.69 | 0.1041 | 3.76 | 0.0021 | 1.69 | 0.0185 |

| 50-day root forks* | 145 | 0.56 | 1.50 | 0.2230 | 3.69 | 0.0024 | 2.35 | 0.0003 |

| 50-day root diameter (mm)* | 145 | 0.64 | 58.21 | <0.0001 | 4.39 | 0.0006 | 1.55 | 0.0412 |

| 50-day % fine roots (<0.2 mm) | 145 | 0.65 | 40.05 | <0.0001 | 6.46 | <0.0001 | 1.83 | 0.0079 |

| 50-day (<0.1 mm)* | 145 | 0.57 | 0.12 | 0.7291 | 3.32 | 0.0051 | 2.50 | 0.0001 |

| 50-day (0.101–0.2 mm)* | 145 | 0.49 | 3.91 | 0.0509 | 2.82 | 0.0144 | 1.70 | 0.0169 |

| 50-day (0.301–0.4 mm)* | 145 | 0.53 | 3.67 | 0.0584 | 6.15 | <0.0001 | 1.55 | 0.0398 |

| 50-day (>0.4 mm)* | 145 | 0.64 | 37.90 | <0.0001 | 5.38 | <0.0001 | 2.02 | 0.0026 |

| 100-day traits | ||||||||

| 100-day total weight (mg)* | 49 | 0.46 | 7.45 | 0.0093 | 4.80 | 0.0009 | – | – |

| 100-day shoot weight (mg)* | 50 | 0.42 | 7.22 | 0.0103 | 4.11 | 0.0025 | – | – |

| 100-day root weight (mg)* | 49 | 0.44 | 6.39 | 0.0154 | 4.40 | 0.0016 | – | – |

| 100-day leaf no.* | 482 | 0.57 | 66.34 | <0.0001 | 39.66 | <0.0001 | 6.17 | <0.0001 |

Sites represent collection locations within invaded and uninvaded areas. At 100 days, root, shoot, and total weights were only measured for one plant per family, and therefore, family is not indicated as an analysis factor for these traits; this is indicated by ‘–’. Numerator degrees of freedom for the factors status, site, and family are 1, 6, and 42, respectively. Significant factors (α = 0.05) are highlighted in bold. Asterisks demark traits whose values were log-transformed for analysis.

Results

At 100 days, E. multisetus plants grown in competition with B. tectorum had 81.4% less total biomass (P < 0.0001, F1,100 = 46.88, r2 = 0.32), 70% less root biomass (P < 0.0001, F1,100 = 33.15, r2 = 0.25), 90.2% less shoot biomass (P < 0.0001, F1,101 = 51.80, r2 = 0.34), and 82.5% fewer leaves (P < 0.0001, F1,672 = 708.12, r2 = 0.51) than control plants grown without competition. At 100 days, leaf number was highly correlated with total biomass (P < 0.0001, F1,100 = 672.98, r2 = 0.87), root biomass (P < 0.0001, F1,100 = 223.42, r2 = 0.70), and shoot biomass (P < 0.0001, F1,101 = 10005.48, r2 = 0.91). Fifty-day leaf number was also highly correlated with 50-day total, root, and shoot biomass (all P < 0.001). However, at 10 days, leaf number was not significantly correlated with any biomass measure (all P > 0.05), as most plants had ≤3 leaves at this time, regardless of their size.

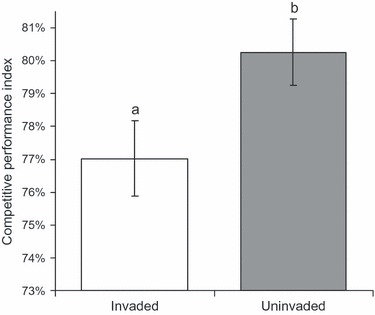

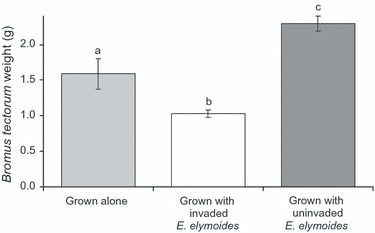

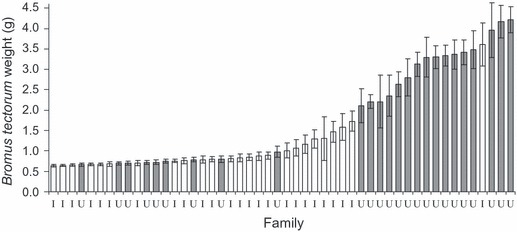

CPI and Bromus tectorum suppression

Competitive performance index varied significantly by invasion status (P = 0.0160, F1,50 = 6.30, r2 = 0.31) and collection site (P = 0.0496, F6,50 = 2.33, r2 = 0.31). Mean CPI of invaded families was significantly lower than that of uninvaded families (Fig. 2), indicating that plants from invaded areas showed a smaller decline in size when grown in competition with B. tectorum. Of the top ten B. tectorum–tolerating families, eight were from invaded areas (not shown). Bromus tectorum shoot biomass varied significantly between control plants (i.e. grown alone), those grown with invaded and uninvaded E. multisetus (P < 0.0001, F2,508 = 60.55, r2 = 0.19, Fig. 3). Bromus tectorum shoot biomass was highest when grown with uninvaded E. multisetus, followed by B. tectorum alone, and smallest when grown with invaded E. multisetus (Fig. 3). Bromus tectorum weight also varied significantly among the E. multisetus families with which it was grown (P < 0.0001, F42,476 = 5.73, r2 = 0.68, Fig. 4). Additionally, ranking of B. tectorum biomass by family revealed that seven of the ten families with the lowest B. tectorum biomass (i.e. most suppressive) were from invaded areas (Fig. 4).

Figure 2.

Relative competitive performance index (CPI) of Elymus multisetus plants that differ in their exposure to Bromus tectorum in the field. Values are means ± SE. Letters represent significant differences between plants from invaded an uninvaded areas (α = 0.05). Plants with lower CPI values are better tolerators of competition, showing a smaller reduction in biomass when growth with B. tectorum.

Figure 3.

Bromus tectorum shoot biomass production when grown with Elymus multisetus seedlings that differ in invasion history. Values are means ± SE, and letters represent significant differences between groups (α = 0.05). Lower B. tectorum weight signifies a greater suppressive effect and is seen in plants collected from invaded areas.

Figure 4.

Elymus multisetus families varied significantly in their effect on Bromus tectorum weight. Values are family means ± SE. Families collected from invaded areas are labeled ‘I’ and colored white, while families from uninvaded areas are labeled ‘U’ and colored gray.

Growth traits in a competitive environment

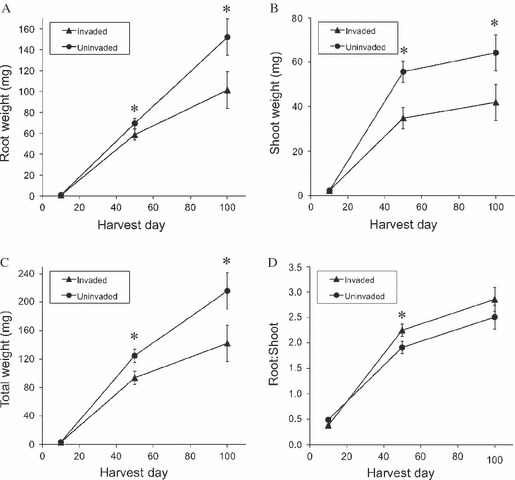

When grown in competition with B. tectorum, E. multisetus seedlings exhibited 14 growth traits that varied significantly by invasion status and 19 growth traits that varied significantly by family (Table 1). Of the 23 growth traits that varied significantly by invasion status or family, 61 (14 traits) were found in the 50-day harvest group when we had increased statistical power because of greater sample size, while none were from the 10-day harvest group. Field-collected seeds from invaded areas exhibited significantly lower seed weights (4.32 ± 0.046 mg) than uninvaded plants (4.78 ± 0.039 mg, Table 1), and these differences persisted in seeds collected from noncompeting control plants grown in common garden (P < 0.0001, F1,200 = 209.72, r2 = 0.91). Seeds produced in the common garden were larger than field-collected seeds, but invaded plants still produced smaller seeds (5.2 ± 0.04 mg) than uninvaded plants (6.1 ± 0.04 mg). Additionally, at each harvest date, invaded plants exhibited lower root, shoot, and total biomass, with significant differences in shoot and total biomass at 50 days and in all three measures at 100 days (Table 1; Fig. 5A–C). Invaded plants exhibited significantly lower early leaf growth rates (0.33 ± 0.013 leaves added; 0.26 ± 0.013 cm leaf length gained, Table 1) than uninvaded plants (0.45 ± 0.018 leaves added; 0.39 ± 0.035 cm leaf length gained, Table 1). Invaded plants exhibited higher R:S at 50 and 100 days, but not at 10 days; this difference was significant at 50 days (Table 1; Fig. 5D). At both 50 and 100 days, invaded plants had significantly lower leaf numbers than uninvaded plants (Tables 1 and 2). The average root diameter of invaded plants at 50 days was significantly smaller than that of uninvaded plants (Tables 1 and 2). The total length of large diameter roots (>0.4 mm) varied significantly by invasion status, with uninvaded plants exhibiting greater length of large diameter roots than invaded plants (Tables 1 and 2). Finally, at each harvest date, invaded plants exhibited higher percentages of fine roots than uninvaded plants, with significant differences at 50 days (Tables 1 and 2). Four root diameter size classes exhibited detectable family-level differences at 50 days, while only one family-level difference in root distribution was detected at 10 days (Table 1).

Figure 5.

Elymus multisetus size and allocation, for seedlings collected from invaded and uninvaded areas. Values are means ± SE at the three harvest events at 10, 50, and 100 days from peak emergence. Asterisks represent significant differences (α = 0.05) between means on a given harvest day.

Table 2.

Values for growth traits of Elymus multisetus grown in competition with Bromus tectorum by invasion status from three different harvest dates

| 10 day | 50 day | 100 day | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uninvaded | Invaded | Uninvaded | Invaded | Uninvaded | Invaded | |

| Leaf number | 1.22 (0.06) | 1.20 (0.06) | 8.04 (0.60) | 6.32 (0.46) | 10.84 (0.36) | 7.81 (0.27) |

| Root length (cm) | 17.12 (0.97) | 16.80 (0.87) | 671.18 (44.97) | 684.01 (43.54) | 1067.57 (107.53) | 1160.37 (154.01) |

| Root tips | 49.92 (5.12) | 48.80 (3.88) | 1535.03 (130.21) | 1389.32 (120.84) | 4026.08 (467.44) | 3717.69 (538.23) |

| Root forks | 49.22 (3.78) | 51.88 (4.87) | 3361.81 (364.69) | 3926.24 (365.90) | 7143.76 (1022.56) | 8096.50 (1537.62) |

| Root diameter (mm) | 0.32 (0.01) | 0.31 (0.01) | 0.26 (0.01) | 0.21 (0.01) | 0.23 (0.01) | 0.21 (0.01) |

| % fine roots (<0.2 mm) | 0.34 (0.02) | 0.39 (0.02) | 0.72 (0.01) | 0.78 (0.01) | 0.74 (0.01) | 0.78 (0.01) |

| Root diameter size classes (root length in cm) | ||||||

| <0.1 mm | 1.86 (0.22) | 1.68 (0.15) | 216.22 (20.91) | 237.86 (21.85) | 423.41 (49.67) | 451.23 (66.27) |

| 0.101–0.2 mm | 4.09 (0.37) | 4.92 (0.37) | 269.78 (15.24) | 295.20 (14.42) | 359.96 (28.81) | 451.00 (52.80) |

| 0.201–0.3 mm | 2.60 (0.19) | 2.49 (0.20) | 46.24 (3.19) | 49.78 (3.15) | 81.22 (8.42) | 78.60 (10.14) |

| 0.301–0.4 mm | 6.37 (0.43) | 5.65 (0.37) | 46.56 (3.62) | 49.34 (2.94) | 80.49 (8.79) | 80.12 (9.86) |

| >0.4 mm | 2.15 (0.21) | 2.03 (0.24) | 90.67 (6.86) | 50.29 (5.62) | 119.38 (19.02) | 96.32 (19.74) |

Values are untransformed means (SE). Significant differences between traits are displayed in Table 1.

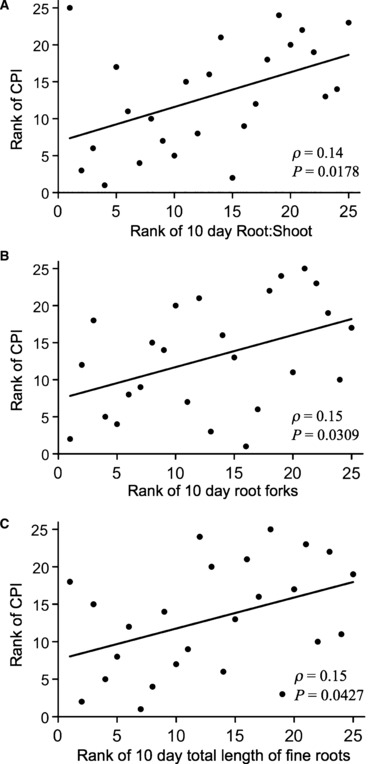

Traits correlated with CPI

Within uninvaded families, three growth traits were significantly correlated with CPI: 10-day R:S (P = 0.0178), 10-day root forks (P = 0.0427), and 10 day length of small diameter roots (0.101–0.200 mm, P = 0.0309). Lower CPI (i.e. greater competitive ability) was correlated with higher 10-day R:S, more root forks, and greater total length of small diameter roots (Fig. 6). While 10-day root forks did not vary significantly between families when considering plants from both invaded and uninvaded areas (Table 1), among only uninvaded plants, 10-day root forks varied significantly by family (P = 0.0224, F21,49 = 2.13, r2 = 0.70). Neither 10-day R:S nor the length of small diameter roots varied between families within uninvaded plants. Analysis of all harvested plants did not detect differences between invaded and uninvaded plants for 10-day root forks, R:S, or small diameter (0.101–0.200 mm) roots. For these three traits, power analysis revealed large sample size requirements (>1000) to detect invasion status differences.

Figure 6.

Ten-day root traits that are significantly correlated with competitive performance index (CPI) in uninvaded families. Traits are graphed by performance rank. To produce an intuitive graph, lower numeric value of rank signifies better competitive performance (i.e. the lowest CPI value is ranked ‘1’) and the greatest R:S, root length, or number of root forks are also ranked ‘1’.

Influence of seed weight on performance

Several early growth traits were significantly affected by seed weight. Larger seeds were more likely to emerge (P < 0.0001, F1,989 = 30.20, r2 = 0.03; nonemergent: 3.8 ± 0.1 mg; emergent: 4.6 ± 0.02 mg). Ten-day root biomass (P < 0.0001, F2,99 = 28.13, r2 = 0.22), shoot biomass (P < 0.0001, F2,100 = 26.62, r2 = 0.22), and total biomass (P < 0.0001, F2,99 = 36.10, r2 = 0.27) increased with increasing seed weight. The length of roots in the three largest diameter classes root classes also increased with increasing seed weight (all P < 0.02). No 50-day or 100-day growth traits were affected by seed weights (all P > 0.05). Neither CPI nor B. tectorum biomass were affected by initial seed weight (P > 0.05).

Discussion

Evidence is emerging that biologic invasions can produce rapid evolutionary change in native plant populations (Callaway et al. 2005; Lau 2006; Mealor and Hild 2007; Cipollini and Hurley 2008; Leger 2008; Ferrero-Serrano et al. 2010). Our findings were consistent with the hypothesis that B. tectorum is exerting a strong selection pressure on native grass populations in the Great Basin: we found that E. multisetus seedlings from invaded areas were more tolerant of competition and better able to suppress B. tectorum than plants from nearby uninvaded areas. In the Great Basin, B. tectorum invasion is associated with other disturbances such as heavy grazing and fire. Therefore, trait differences observed across the invasion boundary in this study may result from additional factors that affect plant fitness, including grazing history or soil type, both of which are known to differ between invaded and uninvaded collection sites. Nonetheless, as confirmed by our results, competition with B. tectorum is known to have strong effects on the fitness of perennial native plants; wholesale invasion certainly has the ability to impose strong selection on such plants. Regardless of the number of selective agents involved, results from this type of experiment can identify plants that perform well in the presence of B. tectorum and that may offer the best potential for restoring invaded rangelands.

The ability to suppress B. tectorum biomass varied significantly by family, indicating genetic variation for this trait exists in natural populations. Although the difference in B. tectorum tolerance was small-only a 3% decrease in CPI for invaded plants, B. tectorum suppression was 30% higher for invaded plants than uninvaded plants. We do not know whether these differences are sufficient to provide a measurable advantage to E. multisetus from invaded populations when growing in a natural setting. Field testing is underway to determine whether the lower CPI and greater ability to suppress B. tectorum exhibited by invaded seedlings will result in greater survival of these plants in invaded areas.

The findings from both our correlative analysis and our examination of shifts in traits suggest that root growth plays a significant role in E. multisetus seedling performance when in competition with B. tectorum. Our most conservative approach for finding adaptive traits was a three-step process of assessing which traits were correlated with CPI within the presumed ancestral gene pool (i.e. uninvaded areas), determining the level of genetic variation in these traits, and examining whether trait values have shifted in the invaded populations. Of the 47 growth traits measured, three were correlated with CPI and all were related to root growth at 10 days. Although type I statistical errors are possible when analyses are conducted on a large number of traits, the fact that all CPI-correlated traits were identified from the earliest seedling stage suggests that these relationships are biologically important, rather than statistical artifacts. Greater tolerance to competition was associated with greater fine root production, higher R:S, and more root forking in young seedlings (Fig. 6). We did not detect a shift across invasion status for these traits, indicating either that traits have not shifted in response to B. tectorum or that we lacked the power to detect a shift. Identifying traits that are easier to measure and are reasonable proxies for root traits (e.g. resource capture) could increase sample sizes and improve the resolution of this method. Differences in root traits were also observed in our broader comparative analysis. Invaded plants produced a significantly higher percentage of fine roots and roots of smaller average diameter at 50 days (Tables 1 and 2). At 50 and 100 days, invaded plants allocated a relatively greater proportion of biomass to root production (Fig. 5).

When competition is mostly for soil resources (e.g. in situations with low soil fertility or high water stress), allocation to below-ground resource capture (measured by high R:S, high specific root length, high fine root production) improves plant performance (McGraw and Chapin 1989; Aerts et al. 1991; Tilman and Wedin 1991; Casper and Jackson 1997; Aerts and Chapin 2000). Several mechanisms have been suggested to explain the importance of fine roots in resource acquisition, including improved opportunistic nutrient foraging (Fitter 1994), adventitious root production in ephemeral nutrient patches (Drew et al. 1973; Robinson et al. 1999), and enhanced nitrogen uptake at terminal roots (Pregitzer et al. 2002). Fine root production and increased root biomass have been linked to resource capture and competitive ability in Great Basin plants (e.g. Bilbrough and Caldwell 1997; James et al. 2009). Root forks may contribute to increased competitive ability in nutrient-poor environments, where root morphology rather than physiology may confer the greatest advantage in nutrient uptake ability (Aerts 1999). For example, in an examination of genetic variation of root morphology in white clover, it was suggested that genotypes with a high number of root tips and forks will possess highly branched root systems that can explore a larger volume of soil per unit root weight, thereby improving nutrient uptake (Jahufer et al. 2008).

Both alone and in competition with B. tectorum, invaded plants were smaller than uninvaded plants. They possessed fewer leaves (Tables 1 and 2), had lower total, root, and shoot biomass (Table 1; Fig. 5), and added biomass more slowly. Nonetheless, seedlings from plants collected from B. tectorum-invaded areas were better at suppressing B. tectorum. This result is contrary to the prevailing theory that greater plant size confers greater competitive ability (Gaudet and Keddy 1988; Keddy et al. 2002). There are other plant–plant interactions besides direct competition that can result in the appearance of competitive advantage. For example, it is possible that some plants reduce the size of their neighbors releasing an allelopathic compound or stimulating the growth of soil organisms that inhibit plant growth, rather than superior resource capture (Allen and Allen 1986; Mahall and Callaway 1992). Although we did not investigate these mechanisms, they may account for our observed disassociation between biomass and competitive ability.

Beyond seeing an unexpected negative relationship between E. multisetus size and competitive ability, we observed that B. tectorum produced significantly more biomass when grown with E. multisetus from uninvaded areas than when it was grown alone, potentially indicative of a facilitative effect (Fig. 3). Interactions between plants are increasingly recognized to contain facilitative components through mechanisms such as soil aeration, root exudation (which can facilitate nutrient availability or alter biotic soil communities), or amelioration of abiotic stress (reviewed in Brooker et al. 2008). We do not know which, if any, of these mechanisms are responsible for the apparent facilitative effect of larger E. multisetus seedlings from uninvaded areas on B. tectorum, but a similar facilitative relationship has been observed in interactions between other desert annual forbs and their competitors (E. Leger, unpublished data). Results of this experiment suggest that a mechanism more complex than a positive relationship between size and competitive ability may be involved in interactions between plants in arid systems.

Our finding that smaller native plants possessed greater tolerance to B. tectorum competition than larger plants may not be that unusual; there can be adaptive value in being a small plant (Aarssen et al. 2006), especially in desert systems. Size does not always predict the impact of resource limitation: in a study of six annual species, greater biomass in isolation did not confer advantage in offspring production under competition; in fact, the most fecund species under competition exhibited relatively small biomass in isolation (Neytcheva and Aarssen 2008). Through its high seed production and soil water exploitation, B. tectorum can drastically reduce resources for native grass seedling establishment (Melgoza et al. 1990), creating highly competitive conditions where small size may be advantageous. Furthermore, in arid systems where plants are often water stressed, there can be disadvantages to greater biomass (e.g. higher transpiration and tissue maintenance costs) that result in mortality; smaller seedlings have shown a greater ability to survive drought conditions (Hendrix et al. 1991).

Invaded plants were not only smaller seedlings; they also had smaller seeds than uninvaded plants. Within a species, bigger seeds typically produce bigger seedlings, though the effect often weakens after development of the first photosynthetic tissue (e.g. Stanton 1984; Kitajima 2007). Our results were consistent with this pattern, with larger seeds producing larger seedlings for both invaded and uninvaded sources at 10 days, while initial seed weight was not significantly related to B. tectorum tolerance, B. tectorum suppression, or any 50- or 100-day growth traits, indicating that the importance of seed weight diminished over time. Nongenetic maternal provisioning can influence seed size (Roach and Wulff 1987); however, it is unlikely that larger seed size of uninvaded plants was due purely to maternal effects, as seed size differences persisted in seed collected from plants grown in a common garden, which is consistent with some degree of genetic control. Seed size is not the only growth trait that can be influenced by maternal environment, and as plants evaluated in this experiment were field collected, there are other maternal environment effects that may have affected performance which were not evaluated here. Given the large variation in family performance (Table 1, Fig. 4), even among plants that were experiencing the same maternal environment, it is likely that there was a genetic component to the differences we found between families and populations, and between invaded and uninvaded areas.

We observed family-level variation at a high frequency, which is evidence that many growth traits are inherited (Table 1). Genetic variation in fitness-related traits is the basis for natural selection, and greater genetic variation represents increased evolutionary potential and a greater likelihood of long-term population persistence (Frankel 1974; Stockwell et al. 2003). Elymus multisetus and E. elymoides are known to have a high degree of morphological variation among populations (Jones et al. 2003), relatively high amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) diversity within populations compared to other perennial grass species (Larson et al. 2003), and our work demonstrates that E. multisetus also has a large amount of family-level genetic variation in growth traits. Because these grasses occur in a wide range of habitats across the Great Basin and are relatively tolerant of disturbance (Jones 1998), it is possible that the large amount of variation observed within these species is a result of their relatively large range sizes, persistence under recent disturbance, and high population densities. Populations with low genetic diversity may not possess sufficient evolutionary potential to persist under new sources of disturbance, such as climate change, land use changes, or new biologic invasions (Rice and Emery 2003; Harris et al. 2006). Although not all the inherited traits we measured were related to performance in greenhouse conditions, the level of genetic variation that we detected may improve the chances for long-term persistence of E. multisetus populations in a changing environment.

The ability of native populations to evolve in response to B. tectorum invasion has significant implications for the management and restoration of invaded communities. If long-invaded populations possess increased tolerance and competitive ability with B. tectorum (Figs 2 and 3), then seed from invaded populations could be an effective tool in restoring nearby B. tectorum-degraded areas. However, seed selection need not be limited to long-invaded populations, as there exists significant genetic variation in how seedlings respond to B. tectorum within uninvaded populations (Fig. 4). Screening plants for inherited performance-related traits and the subsequent choice of genotypes or populations that exhibit high tolerance or suppression of B. tectorum for use in restoration may improve restoration success. Additional traits may be important for survival, growth, and reproduction in B. tectorum-invaded areas, including germination timing, fire and/or grazing tolerance, and disease resistance, which also warrant investigation.

One final consideration for land managers is that restoration projects often introduce large volumes of seed into an ecosystem and may affect both the quantity and quality of local genetic variation. Commercially available seed is often derived from a single source population and sometimes even from a single genotype (Young et al. 2003; Jones and Larson 2005; Shaw et al. 2005). Because nonlocal genotypes can have a deleterious effect on the fitness of local populations (Waser et al. 2000; Montalvo and Ellstrand 2001), there is widespread concern about genetic swamping during large-scale restoration (Montalvo et al. 1997; Hufford and Mazer 2003; McKay et al. 2005). The impact of large-scale seeding on the genetic integrity of existing native populations and the ecosystem as a whole remains poorly understood (Knapp and Dyer 1998; Broadhurst et al. 2008). If B. tectorum-invaded populations are rapidly evolving novel genotypes, then the introduction of high quantities of nonlocal seed near long-invaded populations may reduce both their fitness and evolutionary potential.

Conclusions

The invasion of B. tectorum is converting large areas of the Great Basin from native perennial-dominated to B. tectorum-dominated plant communities; however, some native plants are able to persist in these invaded areas and may evolve in response to long-term B. tectorum presence. Our findings were consistent with the hypothesis that B. tectorum is exerting strong selective pressure on native grass populations in the Great Basin. This study provides examples of two methods for assessing potentially adaptive growth traits: (i) directly testing which traits correlate with increased performance, in either greenhouse or field settings; (ii) comparing traits of successful populations (identified by persistence in invaded areas) with plants growing in uninvaded areas. Both methods have the potential to identify important traits for persistence of native plants in invaded, disturbed, or altered environments. The ability to identify which traits are beneficial and the degree of genetic variation in these traits will help to advance our understanding of the mechanisms of contemporary evolutionary change. It can also serve a practical function by informing management and restoration of native populations in invaded or otherwise disturbed areas.

Acknowledgments

Erin Espeland, Erin Goergen, Akiko Endo, Anna Koster, Sandra Li, Phil Samuels, Kestrel Schmidt, Cassandra Woodward and Hiroaki Zamma assisted with data collection and field work. Matt Forister and Mary Peacock provided helpful suggestions on the manuscript. Jan Dawson, Chris Ross, and the California Department of Fish and Game provided historical information and access to the seed collection sites.

References

- Aanderud ZT, Bledsoe CS, Richards JH. Contribution of relative growth rate to root foraging by annual and perennial grasses from California Oak Woodlands. Oecologia. 2003;136:424–430. doi: 10.1007/s00442-003-1275-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarssen LW, Schamp BS, Pither J. Why are there so many small plants? Implications for species coexistence. Journal of Ecology. 2006;94:569–580. [Google Scholar]

- Aerts R. Interspecific competition in natural plant communities: mechanisms, trade-offs and plant-soil feedbacks. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1999;50:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Aerts R, Chapin FS. The mineral nutrition of wild plants revisited: a re-evaluation of processes and patterns. Advances in Ecological Research. 2000;30:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Aerts R, Boot RGA, Vanderaart PJM. The relation between aboveground and belowground biomass allocation patterns and competitive ability. Oecologia. 1991;87:551–559. doi: 10.1007/BF00320419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre L, Johnson DA. Influence of temperature and cheatgrass competition on seedling development of 2 bunchgrasses. Journal of Range Management. 1991;44:347–354. [Google Scholar]

- Allen EB, Allen MF. Water relations of xeric grasses in the field – interactions of mycorrhizas and competition. New Phytologist. 1986;104:559–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1986.tb00656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo JT, Jones TA, Johnson DA. Seedling growth of Intermountain perennial and weedy annual grasses. Journal of Range Management. 1998;51:584–589. [Google Scholar]

- Bilbrough CJ, Caldwell MM. Exploitation of springtime ephemeral N pulses by six Great Basin plant species. Ecology. 1997;78:231–243. [Google Scholar]

- Booth MS, Caldwell MM, Stark JM. Overlapping resource use in three Great Basin species: implications for community invasibility and vegetation dynamics. Journal of Ecology. 2003;91:36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley BA, Mustard JF. Identifying land cover variability distinct from land cover change: cheatgrass in the Great Basin. Remote Sensing of Environment. 2005;94:204–213. [Google Scholar]

- Britton CM, McPherson GR, Sneva FA. Effects of burning and clipping on 5 bunchgrasses in eastern Oregon. Great Basin Naturalist. 1990;50:115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Broadhurst LM, Lowe A, Coates DJ, Cunningham SA, McDonald M, Vesk PA, Yates C. Seed supply for broad scale restoration: maximizing evolutionary potential. Evolutionary Applications. 2008;1:587–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2008.00045.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker RW, Maestre FT, Callaway RM, Lortie CL, Cavieres LA, Kunstler G, Liancourt P, et al. Facilitation in plant communities: the past, the present, and the future. Journal of Ecology. 2008;96:18–34. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks ML, D'Antonio CM, Richardson DM, Grace JB, Keeley JE, DiTomaso JM, Hobbs RJ, et al. Effects of invasive alien plants on fire regimes. BioScience. 2004;54:677–688. [Google Scholar]

- Callaway RM, Ridenour WM, Laboski T, Weir T, Vivanco JM. Natural selection for resistance to the allelopathic effects of invasive plants. Journal of Ecology. 2005;93:576–583. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll SP, Loye JE, Dingle H, Mathieson M, Famula TR, Zalucki MP. And the beak shall inherit – evolution in response to invasion. Ecology Letters. 2005;8:944–951. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casper BB, Jackson RB. Plant competition underground. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1997;28:545–570. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers JC, Roundy BA, Blank RR, Meyer SE, Whittaker A. What makes Great Basin sagebrush ecosystems invasible by Bromus tectorum. Ecological Monographs. 2007;77:117–145. [Google Scholar]

- Cipollini KA, Hurley SL. Variation in resistance of experienced and naive seedlings of jewelweed (Impatiens capensis) to invasive garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata. Ohio Journal of Science. 2008;108:47–49. [Google Scholar]

- D'Antonio CM, Vitousek PM. Biological invasions by exotic grasses, the grass fire cycle, and global change. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1992;23:63–87. [Google Scholar]

- Drew MC, Saker LR, Ashley TW. Nutrient supply and growth of seminal root system in barley: effect of nitrate concentration on growth of axes and laterals. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1973;24:1189–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Elton CS. The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants. London: Methuen; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Endler JA. Natural Selection in the Wild. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Evans RD, Rimer R, Sperry L, Belnap J. Exotic plant invasion alters nitrogen dynamics in an arid grassland. Ecological Applications. 2001;11:1301–1310. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer DS, MacKay TFC. Introduction to Quantitative Genetics. Essex, UK: Pearson Education Limited; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero-Serrano A, Hild A, Mealor B. Can invasive species enhance competitive ability and restoration potential in native grass populations? Restoration Ecology. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1526-100X.2009.00611.x. [Google Scholar]

- Fitter A. Architecture and biomass allocation as components of the plastic response of root systems to soil heterogeneity. In: Caldwell M, Pearcy R, editors. Exploitation of Environmental Heterogeneity by Plants. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 305–323. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel OH. Genetic conservation – our evolutionary responsibility. Genetics. 1974;78:53–65. doi: 10.1093/genetics/78.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransen B, De Kroon H, De Kovel CGF, Van den Bosch F. Disentangling the effects of root foraging and inherent growth rate on plant biomass accumulation in heterogeneous environments: a disentangling the effects of root foraging and inherent growth rate on plant biomass accumulation in heterogeneous environments: modeling study. Annals of Botany. 1999;84:305–311. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudet CL, Keddy PA. A comparative approach to predicting competitive ability from plant traits. Nature. 1988;334:242–243. [Google Scholar]

- Harris JA, Hobbs RJ, Higgs E, Aronson J. Ecological restoration and global climate change. Restoration Ecology. 2006;14:170–176. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix SD, Nielsen E, Nielsen T, Schutt M. Are seedlings from small seeds always inferior to seedling from large seeds? Effects of seed biomass on seedling growth in Pastinaca sativa L. New Phytologist. 1991;119:99–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1991.tb01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hironaka M, Sindelar BW. Growth-characteristics of squirreltail seedlings in competition with medusahead. Journal of Range Management. 1975;28:283–285. [Google Scholar]

- Hironaka M, Tisdale EW. Secondary succession in annual vegetation in Southern Idaho. Ecology. 1963;44:810–812. [Google Scholar]

- Hufford KM, Mazer SJ. Plant ecotypes: genetic differentiation in the age of ecological restoration. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2003;18:147–155. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey LD, Schupp EW. Seedling survival from locally and commercially obtained seeds on two semiarid sites. Restoration Ecology. 2002;10:88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey LD, Schupp EW. Competition as a barrier to establishment of a native perennial grass (Elymus elymoides) in alien annual grass (Bromus tectorum) communities. Journal of Arid Environments. 2004;58:405–422. [Google Scholar]

- Jahufer MZZ, Nichols SN, Crush JR, Ouyang L, Dunn A, Ford JL, Care DA, et al. Genotypic variation for root trait morphology in a white clover mapping population grown in sand. Crop Science. 2008;48:487–494. [Google Scholar]

- James JJ. Leaf nitrogen productivity as a mechanism driving the success of invasive annual grasses under low and high nitrogen supply. Journal of Arid Environments. 2008;72:1775–1784. [Google Scholar]

- James JJ, Mangold JM, Sheley RL, Svejcar T. Root plasticity of native and invasive Great Basin species in response to soil nitrogen heterogeneity. Plant Ecology. 2009;202:211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA. Viewpoint: the present status and future prospects of squirreltail research. Journal of Range Management. 1998;51:326–331. [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA, Larson SR. Status and use of important native grasses adapted to sagebrush communities. In: Shaw NL, Pellant M, Monsen SB, editors. Fort Collins, Colorado, and USA: Sagegrouse habitat restoration symposium proceedings: 2001 June 4–7; Boise, ID. Proceedings RMRS-P-38. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station; 2005. pp. 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA, Nielson DC, Arredondo JT, Redinbaugh MG. Characterization of diversity among 3 squirreltail taxa. Journal of Range Management. 2003;56:474–482. [Google Scholar]

- Keddy P, Fraser LH, Wisheu IC. A comparative approach to examine competitive response of 48 wetland plant species. Journal of Vegetation Science. 1998;9:777–786. [Google Scholar]

- Keddy P, Nielsen K, Weiher E, Lawson R. Relative competitive performance of 63 species of terrestrial herbaceous plants. Journal of Vegetation Science. 2002;13:5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima K. Seed and seedling ecology. In: Pugnaire FI, Valladares F, editors. Functional Plant Ecology. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2007. pp. 549–580. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp EE, Dyer AR, Fielder PL, Kareiva PM. Conservation Biology for the Coming Decade. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1998. When do genetic considerations require special approaches to ecological restoration? pp. 345–363. [Google Scholar]

- Larson SR, Jones TA, McCracken CL, Jensen KB. Amplified fragment length polymorphism in Elymus elymoides, Elymus multisetus, and other Elymus taxa. Canadian Journal of Botany-Revue Canadienne De Botanique. 2003;81:789–804. [Google Scholar]

- Lau JA. Evolutionary responses of native plants to novel community members. Evolution. 2006;60:56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leger EA. The adaptive value of remnant native plants in invaded communities: an example from the Great Basin. Ecological Applications. 2008;18:1226–1235. doi: 10.1890/07-1598.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JM, Rees M. Effects of temporal variability on rare plant persistence in annual systems. American Naturalist. 2004;164:350–363. doi: 10.1086/422859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodge DM. Biological invasions – lessons for ecology. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 1993;8:133–137. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(93)90025-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack RN. Invasion of Bromus-tectorum into western North America – an ecological chronicle. Agro-Ecosystems. 1981;7:145–165. [Google Scholar]

- Mack RN, Simberloff D, Lonsdale WM, Evans H, Clout M, Bazzaz FA. Biotic invasions: causes, epidemiology, global consequences, and control. Ecological Applications. 2000;10:689–710. [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil C, Dick JTA, Elwood RW, Montgomery WI. Coexistence among native and introduced freshwater amphipods (Crustacea): habitat utilization patterns in littoral habitats. Archiv Fur Hydrobiologie. 2001;151:591–607. [Google Scholar]

- Mahall BE, Callaway RM. Root communication mechanisms and intracommunity distributions of 2 Mojave Desert shrubs. Ecology. 1992;73:2145–2151. [Google Scholar]

- McGraw JB, Chapin FS. Competitive ability and adaptation to fertile and infertile soils in 2 Eriophorum species. Ecology. 1989;70:736–749. [Google Scholar]

- McKay JK, Christian CE, Harrison S, Rice KJ. “How local is local?”– a review of practical and conceptual issues in the genetics of restoration. Restoration Ecology. 2005;13:432–440. [Google Scholar]

- Mealor BA, Hild AL. Post-invasion evolution of native plant populations: a test of biological resilience. Oikos. 2007;116:1493–1500. [Google Scholar]

- Mealor BA, Hild AL, Shaw NL. Native plant community composition and genetic diversity associated with long-term weed invasions. Western North American Naturalist. 2004;64:503–513. [Google Scholar]

- Melgoza G, Nowak RS, Tausch RJ. Soil water exploitation after fire: competition between Bromus tectorum (cheatgrass) and two native species. Oecologia. 1990;83:7–13. doi: 10.1007/BF00324626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menakis JP, Osborne DM, Miller M. Mapping the cheatgrass-caused departure from historical natural fire regimes in the Great Basin, USA. In: Omi PN, Joyce LA, editors. Fort Collins, CO: Fire, Fuel Treatments, and Ecological Restoration Proceedings, 2002 April 16–18, Fort Collins, CO, pp. 281–287. Proceedings RMRS-P-29. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Montalvo AM, Ellstrand NC. Nonlocal transplantation and outbreeding depression in the subshrub Lotus scoparius (Fabaceae) American Journal of Botany. 2001;88:258–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalvo AM, Williams SL, Rice KJ, Buchmann SL, Cory C, Handel SN, Nabhan GP, et al. Restoration biology: a population biology perspective. Restoration Ecology. 1997;5:277–290. [Google Scholar]

- Nasri M, Doescher PS. Effect of competition by cheatgrass on shoot growth of Idaho fescue. Journal of Range Management. 1995;48:402–405. [Google Scholar]

- Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) 2008. Natural Soil Survey Geographic (SSURGO) Database http://soildatamart.nrcs.usda.gov (accessed on October 30 2008)

- Neytcheva MS, Aarssen LW. More plant biomass results in more offspring production in annuals, or does it? Oikos. 2008;117:1298–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Pregitzer KS, DeForest JL, Burton AJ, Allen MF, Ruess RW, Hendrick RL. Fine root architecture of nine North American trees. Ecological Monographs. 2002;72:293–309. [Google Scholar]

- Rafferty DL, Young JA. Cheatgrass competition and establishment of desert needlegrass seedlings. Journal of Range Management. 2002;55:70–72. [Google Scholar]

- Rice KJ, Emery NC. Managing microevolution: restoration in the face of global change. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2003;1:469–478. [Google Scholar]

- Richards RT, Chambers JC, Ross C. Use of native plants on federal lands: policy and practice. Journal of Range Management. 1998;51:625–632. [Google Scholar]

- Roach DA, Wulff RD. Maternal effects in plants. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1987;18:209–235. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D, Hodge A, Griffiths BS, Fitter AH. Plant root proliferation in nitrogen-rich patches confers competitive advantage. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences. 1999;266:431–435. [Google Scholar]

- Sala OE, Chapin FS, Armesto JJ, Berlow E, Bloomfield J, Dirzo R, Huber-Sanwald E, et al. Biodiversity – global biodiversity scenarios for the year 2100. Science. 2000;287:1770–1774. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaepfer MA, Sherman PW, Blossey B, Runge MC. Introduced species as evolutionary traps. Ecology Letters. 2005;8:241–246. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw NL, Lamber SM, Debolt AM, Pellant M. Increasing native forb seed supplies for the Great Basin. In: Dumroese RK, Riley LE, Landis TD, editors. Fort Collins, CO: Forest and Conservation Nursery Associations Proceedings, 2004 July 1215, Charleston, NC, pp. 94–102. Proceedings RMRS-P-35. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton ML. Seed variation in wild radish – effect of seed size on components of seedling and adult fitness. Ecology. 1984;65:1105–1112. [Google Scholar]

- Stein B, Kutner LS, Adams JS. Precious Heritage: The Status of Biodiversity in the United States. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell CA, Hendry AP, Kinnison MT. Contemporary evolution meets conservation biology. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2003;18:94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Stohlgren TJ, Jarnevich C, Chong GW, Evangelista PH. Scale and plant invasions: a theory of biotic acceptance. Preslia. 2006;78:405–426. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss SY, Lau JA, Carroll SP. Evolutionary responses of natives to introduced species: what do introductions tell us about natural communities? Ecology Letters. 2006;9:354–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilman D, Wedin D. Plant traits and resource reduction for 5 grasses growing on a nitrogen gradient. Ecology. 1991;72:685–700. [Google Scholar]

- Waser NM, Price MV, Shaw RG. Outbreeding depression varies among cohorts of Ipomopsis aggregata planted in nature. Evolution. 2000;54:485–491. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson M. Biological Invasions. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Young JA, Evans RA. Squirreltail seed germination. Journal of Range Management. 1977;30:33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Young JA, Major J, Evans RA. Alien plants in great basin. Journal of Range Management. 1972;25:194–201. [Google Scholar]

- Young JA, Clements CD, Jones T. Germination of seeds of big and bottlebrush squirreltail. Journal of Range Management. 2003;56:277–281. [Google Scholar]