Abstract

Laboratory studies on associations between disease resistance and susceptibility and major histocompatibility (MH) genes in Atlantic salmon Salmo salar have shown the importance of immunogenetics in understanding the capacity of populations to fight specific diseases. However, the occurrence and virulence of pathogens may vary spatially and temporally in the wild, making it more complicated to predict the overall effect that MH genes exert on fitness of natural populations and over several life-history stages. Here we show that MH variability is a significant determinant of salmon survival in fresh water, by comparing observed and expected genotype frequencies at MH and control microsatellite loci at parr and migrant stages in the wild. We found that additive allelic effects at immunogenetic loci were more likely to determine survival than dominance deviation, and that selection on certain MH alleles varied with life stage, possibly owing to varying pathogen prevalence and/or virulence over time. Our results highlight the importance of preserving genetic diversity (particularly at MH loci) in wild populations, so that they have the best chance of adapting to new and increased disease challenges as a result of projected climate warming and increasing aquaculture.

Keywords: Atlantic salmon, freshwater life stages, major histocompatibility, natural selection, Salmo salar

Introduction

Understanding the genetic basis of the immune response in fish is critical for the conservation of wild stocks that are under threat from many sources. Disease-mediated extinction of local populations is increasingly likely as a consequence of global warming, and the resulting increase in water temperatures that is probably to cause an increase in the diversity and prevalence and/or virulence of pathogens (Harvell et al. 2002; Crozier et al. 2008; Dionne et al. 2009). In addition, commercially important species such as salmonids face additional threats. The increase in salmonid aquaculture (both fish farming and stocking programmes) (ICES 2009) poses significant disease risks to wild populations; wild fish migrating past cages may be exposed to high levels of pathogens (e.g. sea lice) (Krkošek et al. 2007; Ford and Myers 2008; Costello 2009), accidental or deliberate release of farm fish may bring novel pathogens with them into the wild (Johnsen and Jensen 1994; Bergersen and Anderson 1997) and introgression between farmed escapes and wild populations may lead to changes in the variability of immunogenetic loci of wild populations (Coughlan et al. 2006). While direct genetic effects of introgression between wild and hatchery-reared salmon have been demonstrated (McGinnity et al. 2003; Araki et al. 2007), the impact of diseases originating from aquaculture (Håstein and Lindstad 1991; Johnsen and Jensen 1994; McVicar 1997) on the genetic integrity of wild fish populations has not been sufficiently addressed. A better understanding of how disease-mediated selection impacts on wild populations at all life stages is therefore crucial.

The genes of the major histocompatibility (MH) complex (MHC) encode proteins that play a crucial role in the vertebrate immune response (Klein 1986), and possibly as a result of pathogen-driven balancing selection, MHC genes are the most polymorphic coding regions known in vertebrates (Grimholt et al. 2003; Wegner 2008). Pathogen-driven balancing selection may be the result of heterozygote advantage, negative frequency-dependent selection or varying pathogen resistance over space and time. (Hedrick et al. 1999, 2002; Fraser and Neff 2009; Kekäläinen et al. 2009). The high level of polymorphism in MH genes allows populations to mount an immune response to a wide range of pathogens, but this is only possible if populations have enough variability at MH loci and hence are ‘adequately armed to face the challenge of changing environments’ (Miller and Vincent 2008).

Atlantic salmon Salmo salar L. express single classical MH class I, class II alpha and class II beta loci (Grimholt et al. 2002; Stet et al. 2002). As class I and class II MHC genes in teleosts are unlinked and do not form a single complex, they are therefore known simply as MH genes in this taxon (Stet et al. 2002).Associations between MH genes and resistance or susceptibility to several major salmonid diseases, such as amoebic gill disease (Wynne et al. 2007), furunculosis (Langefors et al. 2001; Lohm et al. 2002), sea lice (Glover et al. 2007), bacterial kidney disease (Turner et al. 2007) and infectious salmon anaemia (Grimholt et al. 2003), have been found in farmed populations, and recently, it has been shown that MH genes are linked with increased susceptibility or resistance to myxozoa in the wild (Dionne et al. 2009). There is, therefore, strong evidence that MH variability can have important implications for the ability of salmon populations to fight disease, but much of this evidence comes from laboratory challenges on adults. However, associations of alleles in single challenge experiments to specific infections cannot explain how the extreme diversity of MH genes is maintained (Wegner 2008), and indeed, it is highly unlikely that animals in their natural environment are only exposed to one pathogen at a time. Empirical evidence linking MH variability to survival and fitness in wild natural conditions with probable varying pathogen assemblages is rare, but is needed o ascertain and predict the impact of disease-mediated selection on locally adapted wild populations of salmon.

The Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) is an anadromous fish that spends the first part of its life in fresh water (typically 1–4 years) and a further one to 3 years feeding in the ocean, before returning to natal rivers to spawn. In the first year after hatching, juvenile salmon (parr) are designated as 0+. After the spring of subsequent years parr are designated as 1+, 2+, etc. until they migrate to sea as smolts. We have previously shown that natural selection on MH genes has fitness consequences for salmon in the first 6 months of their life in fresh water (de Eyto et al. 2007). As salmon generally exhibit high mortality (>90%) in the first few months of freshwater life, this life stage would be most likely to experience disease-mediated selection. However, because of their anadromous life cycle, Atlantic salmon are exposed to pathogens in both the marine and freshwater environments, and as a consequence, salmon undergo a number of other potentially large mortality events both prior to smolting and in the sea, and it is likely that MH-determined survival may also be important at several other life stages. The lack of ‘wild immunogenetic’ studies has recently been highlighted (Pedersen and Babayan 2011), particularly the need to understand how immunogenetics interact with all the other variables that affects wild animals over time, such as physiological condition, resource availability and abiotic conditions (McGinnity et al. 2009). As salmon grow from parr to smolts, they experience a wide range of these variables, e.g. two subsequent winters of potential resource limitation and cold weather, possible summer drought as 1+ fish, changing physiology as they prepare to leave fresh water as smolts and varying pathogen virulence and prevalence. To fully ascertain the extent of disease-mediated selection, it is crucial to run an experiment for long enough to trigger the full potential of the adaptive immune response (Eizaguirre and Lenz 2010), which in the case of salmon in fresh water is at least 2 years. It may be that the immunogenetic advantage conferred during the salmon's first life stage (de Eyto et al. 2007) ceases to be important 18 months later, as other factors affecting survival increase. Conversely, it may be that the advantage continues to play an important role throughout the 2 years in fresh water. The aim of this study, therefore, is to assess the relationship between MH alleles and survival of salmon throughout the freshwater phase. We wanted to ascertain whether disease-mediated selection is a determinant for survival over different life stages of salmon, and if so, whether the same alleles associated with survival in parr are also important at later stages of the salmon's development in fresh water.

Materials and methods

Hatchery and field methods

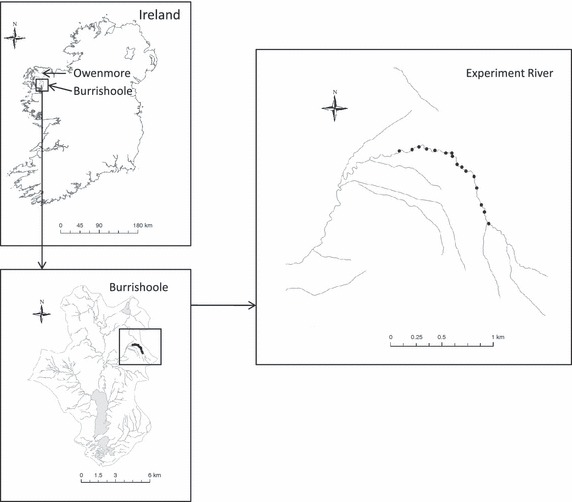

Details of the experiment location and initial set up of family crosses and hatchery procedure can be found in de Eyto et al. (2007). In summary, the experiment was carried out in a contained section of the Srahrevagh River, located in the Burrishoole catchment in western Ireland. As locally adapted fish may not show any signs of disease-mediated selection in their natural environment, we selected wild broodstock from the neighbouring Owenmore system in Co Mayo (Fig. 1). Owenmore fish are not native to the experimental river, and thus are probably not adapted to some of the pathogens endemic to the Burrishoole system. In addition, there has been no history of aquaculture in the Owenmore catchment or the immediate estuary, and thus, fish from this system should have minimal exposure to any aquaculture-associated diseases. To ensure a large degree of immunogenetic diversity, we used a full reciprocal mating system, which produced 63 families with an average of 889 (±155 SE) eggs per family. We excluded natural spawners from the experiment river over the winter of 2001–2002, ensuring that the only salmon hatching in the river in 2002 were from the experiment. This exclusion was facilitated by the presence of a complete upstream and downstream fish trap at the bottom of the Srahrevagh River. In early February 2002, we counted live eggs, mixed the families and 56 031 eggs were planted in the upper reaches of the river in artificial redds (Donaghy and Verspoor 2000; Fig. 1). We randomly sampled approximately 1500 0+ salmon parr from the river in the summer of 2002. A subsample of 746 of these parr was typed for this study. In addition, any juvenile salmon migrating through the trap at the bottom of the river were retained until after the smolt run in 2004 (the vast majority of salmon in this geographic region migrate to sea as 2+ smolts). Tail clips from each individual were preserved in 99% ethanol. Of the fish migrating through the trap, 110 presmolts (migrating in late 2003) and 320 smolts (migrating in February–April 2004) were randomly selected for genetic typing. The total number of migrants (smolts and presmolts combined), therefore, typed for this study was 430 individuals. 0+ and 1+ densities of surviving fish in the river were calculated in August 2002 and 2003 using removal sampling [three pass electrofishing, (Zippin 1958)]. The number of surviving fish was divided by the number of eggs planted in the river to calculate mortality at each life stage.

Figure 1.

Location of the Burrishoole and Owenmore catchments in Ireland (top left), the experiment river in the Burrishoole catchment (bottom left) and the position of the fish trap and artificial redds in the experiment river (right).

Genetic analysis

Natural selection resulting from disease should only be detectable at immunogenetic loci such as MH, while other forces such as genetic drift, migration and mutation should be detectable at control and immunogenetic loci (Garrigan and Hedrick 2003). To distinguish between disease-mediated selection and other forces that may impact on genetic variation, we included eight putatively neutral microsatellite loci as controls. The immunogenetic loci included in this study were as follows: (i) Sasa-UBA-3UTR, a microsatellite marker embedded in the 3′ untranslated region of the MH class I locus; and (ii) Sasa-DAA-3UTR, a minisatellite marker embedded in the 3′ untranslated region of the MH class II alpha locus (Stet et al. 2002; Grimholt et al. 2003). Class II alpha loci are highly polymorphic (Stet et al. 2002) in salmonids, and class II alpha and class II beta alleles form unique haplotypes (Stet et al. 2002); each class II alpha allele is associated with a unique class II beta allele. Therefore, characterization of either the alpha allele or the beta allele is sufficient to describe the polymorphism of class II genes. As previous work on the parr from this study indicated a strong signal of selection on Sasa-DAA alleles (de Eyto et al. 2007), we also unambiguously determined the Sasa-DAA genotype of all parents and progeny. As the relationship between Sasa-DAA alleles or genotypes and Sasa-DAA-3UTR markers is not one-to-one, in that, some of the markers are associated with more than one allele and vice versa, the assignment of Sasa-DAA genotype involved the additional typing of an intron length polymorphism in the (linked) MH class II beta (Sasa-DAB) locus using two primers (DBIn4ctF: ATAGAACAGAATATGGGATGG; DBIn5ctR: TTCATCAGAACAGGACTCTCA). Sasa-DAA/Sasa-DAB haplotypes have, for the most part, a unique combination of embedded minisatellite and microsatellite markers, respectively (H.-J. Megens, unpublished data). In seven of 63 families, this additional typing did not resolve the Sasa-DAA allele, and so these families were excluded from this analysis. This reduced the number of eggs included in the analysis to 51931. Results from both the MH class II embedded marker (Sasa-DAA-3UTR), and also the actual MH class II allele (Sasa-DAA) are presented and discussed in the following sections, and are labelled Sasa-DAA-3UTR (minisatellite) and Sasa-DAA (allele) for clarity.

We typed 746 parr and 430 migrants for the Sasa-UBA-3UTR microsatellite, the Sasa-DAA-3UTR minisatellite, the Sasa-DAA allele and eight control microsatellites [One107 (Olsen et al. 2000); Ssa171, Ssa202, Ssa197 (O'Reilly et al. 1996); Ssp2215, SsaG7SP (Paterson et al. 2004); SSOSL85 (Slettan et al. 1995); SsaD144 (King et al. 2005)] using fluorescently labelled primers. DNA was extracted using the Wizard SVF Genomic DNA Purification System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) or using a Chelex method (Estoup et al. 1996). DNA samples were amplified for all the markers in three multiplex reactions using the Qiagen Multiplex PCR kit (Qiagen Ltd., Crawley, West Sussex, UK) in a final volume of 4 μL with 30 cycles of the PCR profile recommended by manufacturers at 58°C annealing temperature or in ten independent PCRs [PCR profile consisted of 3 min at 95°C, followed by 30 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 56°C (or 50°C for MH Class II) and 30 s at 72°]. Alleles were resolved in a ABI 377 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies Ltd, Paisley, UK) and allele sizes were evaluated against a TAMRA 350/500 size standards, or on 18 or 25 cm 6% polyacrylamide gels using a LiCor 4200 DNA sequencer with allele sizes evaluated against a 50–350 bp size standard and a cocktail of common alleles to account for any potential differences in scoring between machines.

Statistical analysis

The null hypothesis was that under neutrality (i.e. no selection), genotype frequencies in surviving fish would be equal to those expected from parental crosses. The alternative hypotheses would therefore be that either a) frequencies of heterozygotes would be higher than expected in survivors if selection took place as a result of heterozygote advantage or b) that frequencies of certain alleles would be higher than expected in survivors if additive allelic effects conferred fitness advantages. In theory, if disease-mediated selection events had occurred in the river, we would expect no evidence of selection at the eight neutral markers and conversely evidence of selection as a result of either a) or b) (or a combination of both) at the MH loci. A generalized linear model (McCullagh and Nelder 1989) was used for the analysis of the data, which was based on the comparison of observed genotype frequencies in fish surviving after 6 months and those surviving after 2 years, with expected genotype frequencies calculated from parental crosses. This analysis was conducted for each of the eight neutral microsatellite markers, Sasa-UBA-3UTR microsatellite, Sasa-DAA-3UTR minisatellite and the Sasa-DAA allele. Such models are very similar to standard regression models but are more general in that the response variable can be non-normal (e.g. Poisson or binomially distributed). We assumed that the observed number of individuals Yij of each genotype ij at a particular locus (the response variable in the model) followed a Poisson distribution, with an expectation of  . Based on the known number of crossings made between parental genotypes, a measure of the expected number of recaptures under neutrality xij, was calculated. In the simplest case of neutrality, the expected number of recaptures

. Based on the known number of crossings made between parental genotypes, a measure of the expected number of recaptures under neutrality xij, was calculated. In the simplest case of neutrality, the expected number of recaptures  should be proportional to expectations based on the crossings made, xij. Thus, under neutrality, we have

should be proportional to expectations based on the crossings made, xij. Thus, under neutrality, we have  , or, taking logarithmic values,

, or, taking logarithmic values,

| (H00) |

This represents our neutral model H00, which is a generalized linear model (McCullagh and Nelder 1989) with a log-link function and a Poisson response variable. This choice of link function ensures that the response variable takes valid values (e.g. only positive values) for all values of the right-hand side of equation (the linear predictor of the model). The term ln xij plays the role of an offset in the model, that is, a covariate for which the regression coefficient is not estimated but instead is known a priori.

Different extensions of H00 were considered by including terms representing mechanisms of selection. Firstly, terms representing additive allelic effects si and sj of different alleles i and j were added to H00 to form model equation H01.

| (H01) |

If this model fitted the data well, it would indicate that fish with certain alleles had higher survival than fish with different alleles, and that this effect was additive on the log scale. This means that the survival of a particular heterozygote, say ij, lies on the arithmetic mean of the survival of the homozygotes ii and jj on the log scale. Secondly, terms representing a dominance deviation dh where h = 1 for i ≠ j (heterozygotes) and h = 0 for i = j (homozygotes) were added to form model H10.

| (H10) |

With the constraint that d0 = 0, the parameter d1can thus be interpreted as a common increase (or decrease) in survival of heterozygotes relative to the expectation at the arithmetic mean of the respective homozygotes (the expectation under the model with only additive allelic effects, model H01). The advantage of using a common parameter representing dominance deviations for all heterozygote types is increased statistical power and a more parsimonious (simpler) model. We also fitted models where all dominance deviations dij were free parameters (H20). Under this model, the survival of at least one heterozygote differs from the expectation under the additive allelic effects model (H01).

| (H20) |

Finally, Model H11 included both allelic effects and a common dominance deviation:

| (H11) |

The family of fish that the individual belonged to (each family having a different combination of mother and father) was included as a random effect in each model. Theoretically, we could also have tried to model allelic effects and separate dominance deviations together, but estimating all these parameters together along with the family effect proved to be impossible. Thus, five models (H00, H01, H10, H20 and H11) were fitted to observed genotype frequencies of parr and migrant samples and compared separately to the expected genotype frequencies calculated from parental crosses. The parr component of this analysis has been previously published in de Eyto et al. (2007). However, owing to the different number of families included and the inclusion of ‘family’ as a random effect, we include a reanalysis of the parr data here, so that we can make direct comparison with the migrant data.

The constraint that all allelic effects sum to one was introduced to avoid over-parameterization of the models. The intercept and offset term was included in all models and was fitted using the GLM-function of the software package R (R Development Core Team 2004). Models were assessed based on Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) values (Burnham and Anderson 1998), which were calculated for all model alternatives. Nested model alternatives were also tested against each other using standard tests based on the change in deviance (McCullagh and Nelder 1989). In count data like these, the variance of the response variable is typically larger than expected from the model assumptions, a phenomenon known as over-dispersion (McCullagh and Nelder 1989). To assess this, we also computed estimates (McCullagh and Nelder 1989) of the amount of over-dispersion for each selected model, that is, the factor c by which the variance of the response variable exceeds the theoretical variance (the variance is equal to the expectation in case of the Poisson distribution). Thus, an over-dispersion value close to c = 1 indicates that no over-dispersion is present.

We utilised a different statistical approach to test whether allele frequencies differed significantly between parr and migrant samples, as treating the genotype counts at the parr stage as true relative frequencies rather than estimates would be problematic as some of the counts were zero, while they were nonzero in the migrant sample. This makes the inclusion of the ln xij offset term unfeasible and also leads to bias in the estimates of tests of significance of selection between parr and migrant stage. Instead, we used a chi-square test on a n × 2 contingency table, where n is the number of alleles for the locus under consideration. This test was also carried out on egg and parr comparisons and egg and migrant comparisons to elucidate consistent patterns between the GLM models and the chi-square tests.

Results

Mortality was estimated at 89% in the first 6 months (August 2002) after introduction of the eggs into the experiment river (February 2002). Based on density estimates calculated from electrofishing, 36% of fish occurring in the 0+ age class in August 2002 survived to August 2003 (1+ age class), i.e. 64% mortality was recorded between 0+ and 1+ age classes. An estimated 41% of 1+ fish subsequently migrated through the Srahrevagh River trap, either in late summer of 2003 or as presmolts or 2+ smolts. We presume that the 59% of 1+ fish that did not migrate through the trap died, although there may have been a very small proportion surviving to migrate as 3+ smolts, or staying in the river for a third winter as sexually mature male parr. This number, however, is likely to be very small in the Burrishoole catchment. Cumulative estimated mortality from egg to smolt for the study population was 98.7%. It should be noted that survival to migrate through the Srahrevagh River trap does not give a total estimate of freshwater mortality, as the base of the Srahrevagh River is 10 km upstream of the top of the tide in the Burrishoole catchment, so additional mortality may occur during the migration between the trap and the ocean.

Akaike Information Criterion values of the five model alternatives indicated that the observed parr genotypes of five control microsatellites (One107, Ssa171, Ssa202, SsaD144b and Ssp2215) and the Sasa-UBA-3UTR marker were close to expectations based on neutrality and the genotypes of parental crosses. Thus, for these loci, the neutral model (H00) was most appropriate as indicated by lower AIC values than for the alternative models (Table 1). AIC values indicated that observed genotypes of two control microsatellites, Ssa197 and SsaG7SP, were better fitted by models H10 (common heterozygote advantage) and H01 (additive allelic effects), respectively. However, an explicit test of H10 vs H00 for Ssa197 was not significant (P = 0.13), while an explicit test of H01 vs H00 for SsaG7SP test was marginally significant (P = 0.016), making it unlikely that selection had acted at these loci. For SSOSL85, the H10 model had a lower AIC value than the neutral model (H00), and the difference was highly significant (H10 vs H00, P = 0.007). Observed genotypes of the Sasa-DAA-3UTR marker and Sasa-DAA allele also deviated significantly from neutral expectation, and the model with the lowest AIC values was H01, which included additive allelic effects. In summary, the results from the model selection indicate that at parr stage, the observed genotypes of seven of eight control microsatellites conformed to neutral expectations, and that selection occurred at one control microsatellite (heterozygotes at this locus had higher survival) and at both the Sasa_DAA-3UTR marker and allele (fish with certain alleles had higher or lower survival than expected).

Table 1.

Akaike Information Criterion values and of five model alternatives (see text for more detail) for each locus typed in Atlantic salmon surviving in the wild in a section of the Burrishoole river system 6 months (parr) and 2 years (migrants) after introduction. The lowest AIC values (in bold) are considered to be the best fit for that locus. Values for c are the over-dispersion estimates for the best fit model, and n is the number of fish successfully genotyped at that locus

| Parr | Migrants | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H00 | H01 | H10 | H20 | H11 | n | c | H00 | H01 | H10 | H20 | H11 | n | c | |

| One107 | 225.7 | 236.0 | 227.1 | 349.4 | 237.7 | 746 | 1.83 | 272.0 | 271.5 | 272.3 | 371.3 | 273.1 | 428 | 1.31 |

| Ssa171 | 223.5 | 234.1 | 225.1 | 271.6 | 235.5 | 746 | 1.85 | 258.8 | 259.3 | 260.5 | 280.5 | 261.0 | 430 | 1.49 |

| Ssa202 | 178.1 | 184.4 | 180.1 | 237.1 | 186.3 | 746 | 2.00 | 209.8 | 217.0 | 211.7 | 264.1 | 218.9 | 430 | 1.46 |

| Ssa197 | 293.1 | 298.4 | 292.9 | 337.5 | 299.3 | 729 | 1.99 | 268.2 | 270.7 | 270.2 | 310.1 | 272.0 | 367 | 1.28 |

| SsaD144b | 198.1 | 208.9 | 199.3 | 293.1 | 210.8 | 727 | 1.77 | 266.0 | 277.7 | 268.0 | 331.9 | 279.3 | 369 | 1.37 |

| SsaG7SP | 234.2 | 231.0 | 234.0 | 247.6 | 231.9 | 720 | 1.62 | 320.2 | 313.3 | 317.9 | 335.5 | 315.2 | 363 | 1.29 |

| SSOSL85 | 227.9 | 237.6 | 222.7 | 261.4 | 233.8 | 730 | 1.92 | 240.0 | 247.3 | 241.7 | 271.8 | 249.2 | 365 | 1.29 |

| Ssp2215 | 198.7 | 204.2 | 200.6 | 247.4 | 206.1 | 746 | 1.88 | 211.5 | 222.0 | 213.4 | 270.9 | 224.0 | 430 | 1.39 |

| Sasa-DAA allele | 452.5 | 361.8 | 454.4 | 414.9 | 363.7 | 746 | 2.02 | 374.7 | 316.5 | 376.7 | 380.0 | 318.4 | 430 | 1.53 |

| Sasa-DAA-3UTR | 438.5 | 375.1 | 440.3 | 404.6 | 376.1 | 746 | 2.35 | 367.7 | 338.0 | 365.9 | 367.2 | 339.2 | 430 | 1.74 |

| Sasa-UBA-3UTR | 247.4 | 258.7 | 247.4 | 309.6 | 259.0 | 746 | 1.83 | 306.3 | 310.0 | 311.1 | 364.5 | 311.8 | 430 | 1.39 |

Observed genotypes of migrant fish showed a very similar signal. Observed genotypes of six control microsatellites (Ssa171, Ssa202, Ssa197, SsaD144b, SSOSL85 and SSp2215) and the Sasa-UBA-3UTR marker were not significantly different from expectations based on neutrality (H00) (Table 1, lower part). The Sasa-DAA-3UTR marker and Sasa-DAA allele, as well as two control microsatellites (One107 and SsaG7SP), displayed a signal of selection as the best model for these loci included additive allelic effects (H01) (Table 1). In these four cases, explicit tests of H01 vs H00 were significant (P < 0.010).

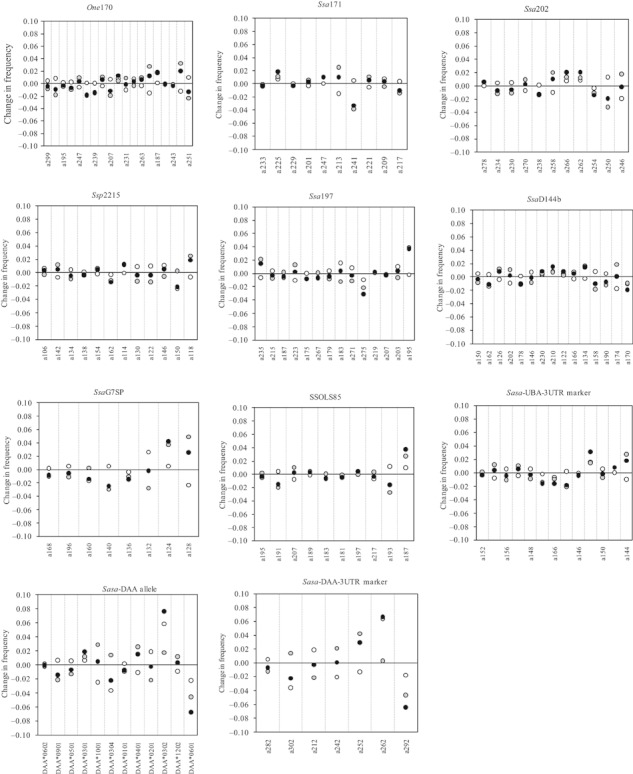

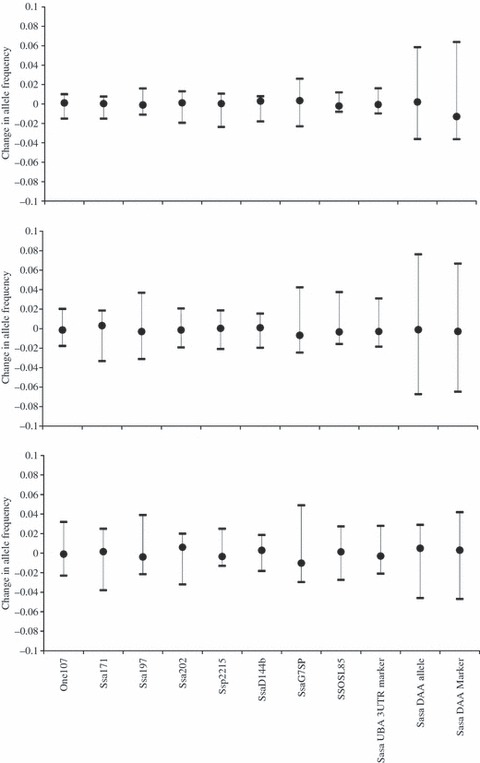

Changes in allele frequencies between egg, parr and migrant were generally very small for most of the loci, with a maximum in the order of 3%. The change in frequency at the Sasa-DAA locus was much more substantial, with the maximum change in allele frequency being 7.6% at DAA*0302 between egg and migrants (Fig. 2). This is further illustrated in Fig. 3 where the pattern and magnitude change in allele frequency is similar for the egg–parr and egg–migrant comparison, with the control microsatellites having a smaller range in frequency change than the two Sasa-DAA loci. The change in allele frequency between parr and migrant is fairly equal across all loci (Fig. 3). However, Chi-squared tests for the changes in allele frequencies indicated that significant changes were observed between parr and migrant for two control microsatellites (One107 and SsaG7SP) and the two Sasa-DAA loci (Table 2), which is consistent with the patterns identified by the GLM analysis.

Figure 2.

Changes in allele frequencies between egg and parr (white circles), egg and migrant (black circles) and parr and migrant (grey circles). Expected egg allele frequencies were calculated from parental crosses and observed allele frequencies in salmon parr and salmon migrants stage were observed after 6 months and 2 years, respectively, in a wild environment. Alleles are ordered left to right with increasing frequency in eggs.

Figure 3.

Changes in allele frequencies between egg and parr (top), and egg and migrant (middle) and parr–migrant (bottom) for eight control microsatellites and three immunogenetic loci. Whiskers indicate minimum and maximum changes in allele frequencies. Allele frequencies at egg stage were calculated from parental crosses, and allele frequencies in salmon parr and salmon migrants stage were observed after 6 months (n = 746) and 2 years (n = 430), respectively, in a wild environment.

Table 2.

Per marker P-values of chi-square tests on n × 2 contingency tables comparing allele frequencies between two life stages indicated above the column; number of alleles n = d.f. + 1. Significant values (P < 0.01) are in bold

| Locus | d.f. | Egg–parr | Egg–migrant | Parr–migrant |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| One_107 | ○ | 0.132 | 0.005 | 0.000 |

| Ssa171 | 9 | 0.638 | 0.014 | 0.072 |

| Ssa197 | 13 | 0.107 | 0.035 | 0.069 |

| Ssa202 | 10 | 0.257 | 0.095 | 0.068 |

| SsaD144b | 14 | 0.270 | 0.172 | 0.196 |

| SsaG7SP | 7 | 0.021 | 0.004 | 0.009 |

| SSOSL85 | 9 | 0.533 | 0.280 | 0.292 |

| Ssp2215 | 11 | 0.129 | 0.206 | 0.210 |

| Sasa-DAA-3UTR | 6 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 |

| Sasa-DAA allele | 11 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Sasa-UBA-3UTR | 12 | 0.419 | 0.030 | 0.178 |

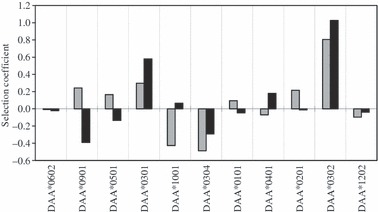

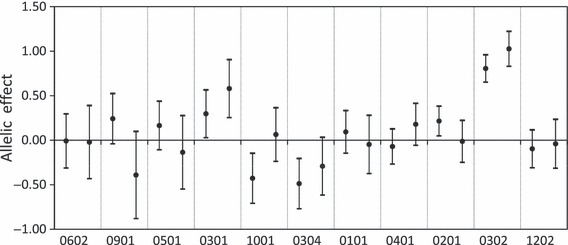

Estimates of the allelic effects (parameters si and sj) were calculated for each Sasa-DAA allele by fitting observed and expected genotype frequencies to model H01. Selection coefficients for each Sasa-DAA allele were then calculated from the estimated allelic effect; for example, an estimated allelic effect of 0.25 means that an individual carrying one copy of this particular allele on average experiences an increase in survival by a factor of e0.25 = 1.28; that is, a 28% increase in survival or a selection coefficient of 0.28, relative to the first allele in the data set. Selection coefficients for the DAA alleles ranged from −0.48 to 0.81 for parr and −0.39 and 1.03 for migrants indicating that within this population, the DAA-specific allele could affect survival negatively by up to 48% or positively by up to 103% (Fig. 4). The DAA alleles *0301 and *0302 were associated with increased survival in both parr and migrant fish, while DAA*0304, *1202 and *0601 were associated with decreased survival in both parr and migrant. In six of 12 alleles, selection was either positive or negative depending on the life stage in question – i.e. the direction of selection varied between life stages; for example, DAA*0901 had a selection coefficient of 0.24 in parr but −0.39 in migrants (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Selection coefficients for Sasa-DAA alleles in salmon surviving at 6 months in their natural environment as parr (grey bars) and at 2 years as migrants (black bars). The selection coefficients are derived from allelic point estimates calculated by fitting observed and expected genotype frequencies to model H01 (see text for details). Alleles are ordered left to right with increasing frequency in eggs. DAA*0601 is not included in the graph as it was used as the baseline in the model, against which all other selection coefficients were measured.

To assess whether large allelic effects (and hence selection coefficients) and sign changes were important, confidence intervals based on standard errors of the allelic estimates (estimate ± z 0.95 *SE) were calculated (Fig. 5). For three alleles, which displayed sign changes in their selection coefficients (DAA*0901, DAA*1001 and DAA*0201), the confidence intervals indicate minimal overlap between confidence intervals of egg–parr and egg–migrant estimates, indicating that the sign change in selection coefficient was important. For the three other alleles, which displayed sign changes (DAA*0501, DAA*0101 and DAA*0401), the confidence intervals overlapped to a large extent between life stages and were not that different from 0. The two alleles that showed the highest degree of positive selection were DAA*0301 and DAA*0302, and the confidence intervals of these alleles did not include zero. Similarly, the confidence intervals of DAA*0304, which was associated with negative selection coefficients at both life stages, were, on the whole, negative. In summary, the confidence intervals around the allelic estimates support the view that three of the alleles displayed a strong selection signal consistent between life stages (positive: *0301 and *0302, negative: *0304), and three displayed a selection signal that varied between life stages (*0901, *1001 and *0201). For the other five alleles (*0501, *0101, *0401, *1202 and *0602), the confidence intervals for allelic estimates were generally centred around zero, which indicates that in this experiment these alleles were probably not associated with survival to any large degree.

Figure 5.

Allelic effects calculated for Sasa-DAA alleles in salmon surviving at 6 months in their natural environment as parr (left bars) and at 2 years as migrants (right bars). Allelic effects are calculated by fitting observed and expected genotype frequencies to model H01 (see text for details). Alleles are ordered left to right with increasing frequency in eggs. Whiskers represent the 95% confidence interval of the estimates. DAA*0601 is not included in the graph as it was used as the baseline in the model, against which all other allelic effects were measured.

Discussion

The results presented here indicate the importance of immune genes in determining survival of salmon throughout their life stages in fresh water. At both parr and migrant stages, allele frequencies for the Sasa-DAA allele and marker deviated significantly from neutrality, while allele frequencies for the majority of control microsatellites and the Sasa-UBA-3UTR marker did not. As natural selection resulting from disease should only be detectable at immunogenetic loci, while other forces such as genetic drift, migration and mutation should be detectable at both control and immunogenetic loci, we conclude that disease-mediated selection during the 2 years of freshwater life was the cause of the deviation of the Sasa-DAA locus from neutrality. Although two of the control microsatellites, One107 and SsaG7SP, are putatively neutral, our results indicate that they might not necessarily be so, and may in fact be linked to or are in linkage disequilibrium with another locus or loci, which were under selection. The additive allelic effects in migrant fish (as indicated by the selection of model H01) were much stronger for the Sasa-DAA immunogenetic locus than for One107 and SsaG7SP, as indicated by the difference between observed and expected allele frequencies, which were substantially larger for the DAA locus than for the control microsatellites (Fig. 3). This indicates that even though there was some evidence of selection on these two control microsatellites, it was not as strong as the selection acting on the DAA loci.

There is still much debate over the mechanism by which MH polymorphism is maintained, and how fitness differences are conferred by MH genes. Heterozygote advantage has been shown to be an important evolutionary mechanism in Arctic charr populations (Kekäläinen et al. 2009), water voles (Oliver et al. 2009), mice (Penn et al. 2002) and salmon (Turner et al. 2007), but has been discounted in other animals (Tollenaere et al. 2008). There is also evidence supporting the view that specific alleles are more important for disease resistance than heterozygosity (Paterson et al. 1998; Schad et al. 2005; de Eyto et al. 2007). The results presented here support the latter view, as additive allelic effects were more important than dominance deviations in determining the survival of an individual in response to disease-mediated selection. While we cannot rule out heterozygote advantage or superiority as playing a role in determining survival in this experiment, we must conclude that it is less important than the role of specific alleles, as demonstrated by the best fit of the H01 (additive allelic effects) to the data over model H10 (common dominance deviations) or H20 (separate dominance deviations). It is worth noting that the roles of heterozygote advantage and frequency-dependant selection (or specific allele advantage) are probably not mutually exclusive (Eizaguirre and Lenz 2010), and as the number of alleles in a population increases, the difficulty in separating out the effects becomes increasingly challenging (Oliver et al. 2009). This is especially true in our case, where we had 56 families and 12 Sasa-DAA alleles in total. A similar experiment with a smaller number of alleles may allow the fitting of a model including additive allelic effects and separate dominance deviations without over-parameterization (Oliver et al. 2009), which was the problem that we encountered in this analysis. However, it is worth noting that the allelic variation we encountered in our experimental population (12 Sasa-DAA alleles) is what we would expect to find in any locally adapted population in this part of Ireland [14 Sasa-DAA alleles were sampled from four rivers close to and including the Burrishoole catchment (Consuegra et al. 2005)], and indeed, it is what we were aiming for when we designed the experiment. This is in line with the suggestion that to test the extent of disease-mediated selection as a result of local immunogenetic adaptation, the allele diversity in the translocated population should reflect the natural diversity present in the wild (Eizaguirre and Lenz 2010). As a result of this trade-off between statistical power and a true representation of the likely adaptive response in a wild population, it is difficult to be definitive about the mechanism accounting for differential survival.

Additive allelic effects are consistent with the theory of frequency-dependant selection, or variable selection in time and space (Hedrick 2002). This study indicates that the second theory may be more applicable to Atlantic salmon, as several Sasa-DAA alleles were significantly associated with positive selection coefficients between egg and parr stage but with negative selection between egg and migrant stage, or vice versa. This is in agreement with the view that temporal variation in selection means that selective mortality in one time period is a poor predictor of selection coefficients during other time periods (Kekäläinen et al. 2009). Temporal variation in selection may be because of different life stages being susceptible to different pathogens, or alternatively, that the prevalence and/or virulence of pathogens may vary seasonally and annually. Spatial variation in pathogenicity is also very likely in the case of the salmon life cycles, as 0+, 1+ and 2+ salmon use different habitats (Bardonnet and Baglinière 2000), which may harbour differing pathogens. As either spatial or temporal variation in selection (or a combination of the two) is a likely cause of the sign changes in selection coefficients between salmon life stages, our results support the theory that the high polymorphism observed at immunogenetic loci may be maintained by a combination of spatial and temporal variation in selection pressures.

This study highlights the fact that experiments carried out at particular life stages (e.g. parr) may be insufficient to gain a full understanding of the action of disease-mediated selection; for example, the two DAA alleles (0501 and 0101) associated with susceptibility to furunculosis in laboratory conditions (Grimholt et al. 2003) were not strongly correlated with survival at parr or migrant stage, even though furunculosis is known to occur in the Burrishoole system. This confirms that resistance or susceptibility in the laboratory does not translate easily to wild conditions, possibly because laboratory studies are generally confined to one age class of fish, most commonly adults (Dionne et al. 2009).

The results presented here show that disease-mediated selection, either carried forward as a selective advantage from the parr mortality event or as a result of subsequent disease episodes, continues to be an important but variable determinant of survival until salmon migrate to sea as smolts. Both of these scenarios are supported by our data; for example, DAA *0301 and DAA*0302 were both strongly associated with positive selection at parr stage, and this large effect was carried forward to the migrant stage, when these two alleles still displayed high levels of positive selection. It is also possible that the same pathogen, which these two alleles were conferring some kind of resistance to, continued to be a factor for 1+ and 2+ fish. In contrast, allele DAA*0901 displayed positive selection at parr stage, but displayed negative selection by the migrant stage. This indicates that fish with this allele, which had survived the initially large mortality event as parr, were disadvantaged during the subsequent 18 months, perhaps as a result of a different pathogen affecting the population. It is interesting to note that the signal of the disease-mediated selection (as indicated by the difference in the scale of allele frequency changes between neutral and Sasa-DAA loci) appears to be strongest at the 0+ life stage of salmon (Fig. 3). This may be simply a reflection of the sheer size of the mortality event, which occurs in the first couple of months after the fry emerge from the redds and the susceptibility of emerged fish to a new habitat. Nevertheless, the fact that three DAA alleles (DAA*0901, DAA*1001 and DAA*0201) displayed a sign change in selection coefficient between parr and migrant stages indicates that disease-mediated selection continues to be an important determinant of survival throughout the freshwater stage of the salmon life cycle, and that the selection event at parr stage is not simply carried forward through the freshwater stages.

In the time period of this study, egg-to-smolt survival (to the experiment stream downstream trap) was 1.3%. In other words, for every 1000 eggs spawned, 13 fish survived to migrate towards the sea. However, freshwater mortality is highly variable, as indicated by the egg-to-smolt survival recorded for the entire Burrishoole catchment, which varied up to 400% between 1969 and 2006 (minimum 0.3%, maximum 1.2%, McGinnity et al. 2009). It has been shown that warmer winters reduce the survival of juvenile salmon in their first 2 years in fresh water in the Burrishoole catchment (McGinnity et al. 2009), and it has been hypothesised that this may be the result of a mismatch between photoperiod-determined emergence of fry and temperature-determined energetics of hibernating salmon. It is also possible that it is the result of disease-mediated selection, which may be greater in warmer winters, as pathogen virulence and diversity has been shown to increase with temperature (Hari et al. 2006; Okamura et al. in press). The results presented here indicate that Sasa-DAA variability within a population can play a significant role in determining which fish survive the freshwater stage of the salmon life cycle, and hence how many will migrate to sea. Disease-mediated selection, therefore, may be an important factor determining the annual variation in freshwater survival in salmon. It is highly likely that disease-mediated selection on salmonids in fresh water as reported in this paper also occurs during the marine phase over very short time periods, particularly, as some of the pathogens associated with MH variability occur at sea, such as sea lice (Glover et al. 2007) and infectious salmon anaemia (Grimholt et al. 2003). The importance of MH genes in determining marine survival may be a fruitful avenue of exploration in trying to understand the continuing decline in marine survival of Atlantic salmon (ICES 2010).

The polymorphic nature of immunogenetic loci such as Sasa-DAA and other MH loci indicate that these loci are capable of adapting to new pathogen challenges, and it has been shown that increasing temperature may be one of the drivers of immunogenetic diversity in populations (Tonteri et al. 2010). Dionne et al. (2007) showed that large-scale genetic variability at a MH class IIβ gene in Atlantic salmon increased with increasing temperature and bacterial diversity in rivers contrary to patterns with neutral microsatellite markers. It is possible, therefore, that climate change may increase selection on MH genes, and hence increase polymorphism within wild populations in the long term, but only if they are not demographically compromised in the short term by a pathogen, which they do not have the ability to fight at a population level. Locally adapted wild populations may be most at risk of extinction in this case. The increasing production of captive-bred fish for aquaculture and stocking and the related disease risks further increase the risk of disease-mediated extinction. The combination of warmer climates and potential increases in novel pathogens and their virulence will undoubtedly put huge pressure on wild populations (Jonsson and Jonsson 2009; McGinnity et al. 2009). While it might be possible to breed disease resistance into cultured strains using information gathered about susceptibility and resistance conferred by specific MH alleles, it would be impractical to attempt this with wild populations. A more practical application of our results would be to avoid interactions between wild and farmed fish by not locating farms where projected changes in temperature are expected to be the most extreme i.e. northern latitudes (McGinnity et al. 2009) In the face of the unpredictable nature of climate change, our results highlight the importance of conserving genetic diversity (in this case immunogenetic diversity), so that wild populations have the greatest chance to adapt to emerging pathogen challenges.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the European Commission (SALIMPACT Q5RS-2001-01185) and the Marine Institute of Ireland. We thank R. Poole, K. Whelan and the field staff of the Burrishoole research facility for their logistical support. PMcG and JC were part supported by the Beaufort Marine Research award in Fish Population Genetics funded by the Irish Government under the Sea Change Programme. This manuscript benefited from the comments provided by two anonymous reviewers.

Data archiving Statement

Data for this study are available in the supplementary data, Table S1.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1. The number of occurrences of alleles of 11 genetic loci in eggs of Atlantic salmon (predicted from parental crosses) and in the same fish surviving in a natural environment after 6 months (parr), and after 2 years (migrants).

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Literature cited

- Araki H, Cooper B, Blouin MS. Genetic effects of captive breeding cause a rapid cumulative fitness decline in the wild. Science. 2007;318:100. doi: 10.1126/science.1145621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardonnet A, Baglinière J-L. Freshwater habitat of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 2000;57:497–506. [Google Scholar]

- Bergersen EP, Anderson DE. The distribution and spread of Myxobolus cerebralis in the United States. Fisheries. 1997;22:6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Model Selection and Multimodal Inference. A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach. New York: Springer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Consuegra S, Megens H, Leon K, Stet RJM, Jordan WC. Patterns of variability at the major histocompatibility class II alpha locus in Atlantic salmon contrast with those at the class I locus. Immunogenetics. 2005;57:16–24. doi: 10.1007/s00251-004-0765-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello MJ. How sea lice from salmon farms may cause wild salmonid declines in Europe and North America and be a threat to fishes elsewhere. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2009;276:3385–3394. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.0771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlan J, McGinnity P, O'Farrell B, Dillane E, Diserud O, de Eyto E, Farrell K, et al. Temporal variation in an immune response gene (MHC I) in anadromous Salmo trutta in an Irish river before and during aquaculture activities. ICES Journal of Marine Science. 2006;63:1248–1255. [Google Scholar]

- Crozier LG, Hendry AP, Lawson PW, Quinn TP, Mantua NJ, Battin J, Shaw RG, et al. Potential responses to climate change in organisms with complex life histories: evolution and plasticity in Pacific salmon. Evolutionary Applications. 2008;1:252–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2008.00033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dionne M, Miller KM, Dodson JJ, Caron F, Bernatchez L. Clinal variation in MHC diversity with temperature: evidence for the role of host-pathogen interaction on local adaptation in Atlantic salmon. Evolution. 2007;61:2154–2164. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dionne M, Miller KM, Dodson JJ, Bernatchez L. MHC standing genetic variation and pathogen resistance in wild Atlantic salmon. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences. 2009;364:1555–1565. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaghy MJ, Verspoor E. A new design of instream incubator for planting out and monitoring Atlantic salmon eggs. North American Journal of Fisheries Management. 2000;20:521–527. [Google Scholar]

- Eizaguirre C, Lenz TL. Major histocompatability complex polymorphism: dynamics and consequences of parasite-mediated local adaptation in fishes. Journal of Fish Biology. 2010;77:2023–2047. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2010.02819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estoup A, Largiader CR, Perrot E, Chourrout D. Rapid one-tube extraction for reliable PCR detection of fish polymorphic markers and transgenes. Molecular Marine Biology and Biotechnology. 1996;5:295–298. [Google Scholar]

- de Eyto E, McGinnity P, Consuegra S, Coughlan J, Tufto J, Farrell K, Megens H, et al. Natural selection acts on Atlantic salmon major histocompatibility (MH) variability in the wild. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2007;274:861–869. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JS, Myers RA. A global assessment of salmon aquaculture impacts on wild salmonids. PLoS Biology. 2008;6:e33. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser BA, Neff BD. MHC class IIB additive and nonadditive effects on fitness measures in the guppy Poecilia reticulata. Journal of Fish Biology. 2009;75:2299–2312. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2009.02449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrigan D, Hedrick PW. Perspective: detecting adaptive molecular polymorphism: lessons from the MHC. Evolution. 2003;57:1707–1722. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover KA, Grimholt U, Bakke HG, Nilsen F, Storset A, Skaala Ã. Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) variation and susceptibility to the sea louse Lepeophtheirus salmonis in Atlantic salmon Salmo salar. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 2007;76:57–65. doi: 10.3354/dao076057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimholt U, Drabløs F, Jørgensen SM, Høyheim B, Stet RJM. The major histocompatability class I locus in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.): polymorphism, linkage analysis and protein modelling. Immunogenetics. 2002;54:570–581. doi: 10.1007/s00251-002-0499-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimholt U, Larsen S, Nordmo R, Midtlyng P, Kjoeglum S, Storset A, Saebø S, et al. MHC polymorphism and disease resistance in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar); facing pathogens with single expressed major histocompatibility class I and class II loci. Immunogenetics. 2003;55:210–219. doi: 10.1007/s00251-003-0567-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hari RE, Livingstone DM, Siber R, Burkhardt-Holm P, Güttinger H. Consequences of climatic change for water temperature and brown trout populations in Alpine rivers and streams. Global Change Biology. 2006;12:10–26. [Google Scholar]

- Harvell CD, Mitchell CE, Ward JR, Altizer S, Dobson AP, Ostfeld RS, Samuel MD. Climate warming and disease risks for terrestrial and marine biota. Science. 2002;296:2158–2162. doi: 10.1126/science.1063699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håstein T, Lindstad T. Diseases in wild and cultured salmon: possible interactions. Aquaculture. 1991;98:277–288. [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick PW. Pathogen resistance and genetic variation at MHC loci. Evolution. 2002;56:1902–1908. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick PW, Parker KM, Miller EL, Miller PS. Major histocompatibility complex variation in the endangered Przewalski's horse. Genetics. 1999;152:1701–1710. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.4.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick PW, Lee RN, Garrigan D. Major histocompatibility complex variation in red wolves: evidence for common ancestry with coyotes and balancing selection. Molecular Ecology. 2002;11:1905–1913. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2002.01579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICES. 2009. Report of the Working Group on North Atlantic Salmon (WGNAS)International Council for the Exploration of the Sea CM 2009/ACOM:06.

- ICES. 2010. Report of the Working Group on North Atlantic Salmon (WGNAS)International Council for the Exploration of the Sea CM 2010/ACOM:09.

- Johnsen BO, Jensen AJ. The spread of furunculosis in salmonids in Norwegian rivers. Journal of Fish Biology. 1994;45:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson B, Jonsson N. A review of the likely effects of climate change on anadromous Atlantic salmon Salmo salar and brown trout Salmo trutta, with particular reference to water temperature and flow. Journal of Fish Biology. 2009;75:2381–2447. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2009.02380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kekäläinen J, Vallunen JA, Primmer CR, Rättyä J, Taskinen J. Signals of major histocompatibility complex overdominance in a wild salmonid population. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2009;276:3133–3140. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.0727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King TL, Eackles S, Letcher BH. Microsatellite DNA markers for the study of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) kinship, population structure, and mixed-fishery analyses. Molecular Ecology Notes. 2005;5:130. [Google Scholar]

- Klein J. The Natural History of the Major Histocompatibility Complex. New York: Wiley & Sons; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Krkošek M, Ford JS, Morton A, Lele S, Myers RA, Lewis MA. Declining wild salmon populations in relation to parasites from farm salmon. Science. 2007;318:1772–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.1148744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langefors Å, Lohm J, Grahn M, Andersen Ø, von Schantz T. Association between major histocompatibility complex class IIB alleles and resistance to Aeromonas salmonicida in Atlantic salmon. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2001;268:479–485. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohm J, Grahn M, Langefors Å, Andersen Ø, Storset A, von Schantz T. Experimental evidence for major histocompatibility complex-allele-specific resistance to a bacterial infection. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2002;269:2029–2033. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullagh P, Nelder JA. Generalized Linear Models. London: Chapman & Hall; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- McGinnity P, Prodöhl P, Ferguson A, Hynes R, Ò Maoileidigh N, Baker N, Cotter D, et al. Fitness reduction and potential extinction of wild populations of Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar, as a result of interactions with escaped farm salmon. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 2003;270:2443–2450. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnity P, Jennings E, de Eyto E, Allott N, Samuelsson P, Rogan G, Whelan K, et al. Impact of naturally spawning captive-bred Atlantic salmon on wild populations: depressed recruitment and increased risk of climate-mediated extinction. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2009;276:3601–3610. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.0799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVicar AH. Disease and parasite implications of the coexistence of wild and cultured Atlantic salmon populations. ICES Journal of Marine Science. 1997;54:1093–1103. [Google Scholar]

- Miller MP, Vincent ER. Rapid natural selection for resistance to an introduced parasite of rainbow trout. Evolutionary Applications. 2008;1:336–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2008.00018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura B, Hartikainen H, Schmidt-Posthaus H, Wahli T. Life cycle complexity, environmental change and the emerging status of salmonid proliferative kidney disease. Freshwater Biology. 2011;56:735–753. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver MK, Telfer S, Piertney SB. Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) heterozygote superiority to natural multi-parasite infections in the water vole (Arvicola terrestris) Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2009;276:1119–1128. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen JB, Kretschmer EJ, Wilson SL, Seeb JE. Characterization of 14 tetranucleotide microsatellite loci derived from sockeye salmon. Molecular Ecology. 2000;9:2185–2187. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.105317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly PT, Hamilton LC, McConnell SK, Wright JM. Rapid analysis of genetic variation in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) by PCR multiplexing of dinucleotide and tetranucleotide microsatellites. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 1996;53:2292–2298. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson S, Wilson K, Pemberton JM. Major histocompatibility complex variation associated with juvenile survival and parasite resistance in a large unmanaged ungulate population (Ovis aries L.) Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America. 1998;95:3714–3719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson S, Piertney SB, Knox D, Gilbey J, Verspoor E. Characterization and PCR multiplexing of novel highly variable tetranucleotide Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) microsatellites. Molecular Ecology Notes. 2004;4:160–162. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen AB, Babayan SA. Wild immunology. Molecular Ecology. 2011;20:872–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn DJ, Damjanovich K, Potts WK. MHC heterozygosity confers a selective advantage against multiple-strain infections. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America. 2002;99:11260–11264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162006499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Development Core Team; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schad J, Ganzhorn JU, Sommer S. MHC constitution and parasite burden in the Malagasy mouse lemur, Microcebus murinus. Evolution. 2005;59:439–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slettan A, Olsaker I, Lie Ø. Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar, microsatellites at the SSOSL25, SSOSL85, SSOSL311, SSOSL417 loci. Animal Genetics. 1995;26:281–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.1995.tb03262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stet RJM, de Vries B, Mudde K, Hermsen T, van Heerwaarden J, Shum BP, Grimholt U. Unique haployptes of co-segregating major histocompatibility class II A and class II B alleles in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) give rise to diverse class II genotypes. Immunogenetics. 2002;54:320–331. doi: 10.1007/s00251-002-0477-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollenaere C, Bryja J, Galan M, Cadet P, Deter J, Chaval Y, Berthier K, et al. Multiple parasites mediate balancing selection at two MHC class II genes in the fossorial water vole: insights from multivariate analyses and population genetics. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2008;21:1307–1320. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonteri A, Vasemagi A, Lumme J, Primmer CR. Beyond MHC: signals of elevated selection pressure on Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) immune-relevant loci. Molecular Ecology. 2010;19:1273–1282. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner SM, Faisal M, DeWoody JA. Zygosity at the major histocompatibility class IIB locus predicts susceptibility to Renibacterium salmoninarum in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) Animal Genetics. 2007;38:517–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2007.01631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner KM. Historical and contemporary selection of teleost MHC genes: did we leave the past behind? Journal of Fish Biology. 2008;73:2110–2132. [Google Scholar]

- Wynne JW, Cook MT, Nowak BE, Elliot NG. Major histocompatibility polymorphism associated with resistance towards amoebic gill diesease in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) Fish and Shellfish Immunology. 2007;22:707–717. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zippin C. The removal method of population estimation. Journal of Wildlife Management. 1958;22:82–90. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.