Abstract

Background/Purpose:

Acne vulgaris is a very prevalent skin disorder and remains a main problem in practice. Recently, phototherapy with various light spectrums for acne has been used. There are some evidences that low-level laser therapy (LLLT) has beneficial effect in the treatment of acne lesions. In this study, two different wavelengths of LLLT (630 and 890 nm) were evaluated in treatment of acne vulgaris.

Materials and Methods:

This study was a single-blind randomized clinical trial. Patients with mild to moderate acne vulgaris and age above 18 years and included were treated with red LLLT (630 nm) and infrared LLLT (890 nm) on the right and left sides of the face respectively, twice in a week for 12 sessions, and clinically assessed at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8.

Results:

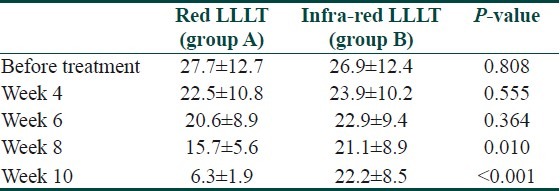

Twenty-eight patients were participated in this study. Ten weeks after treatment acne lesion were significantly decreased in the side treated by 630 nm LLLT (27.7±12.7 to 6.3±1.9) (P<0.001), but this decrease was not significant in the site treated by 890 nm LLLT (26.9±12.4 to 22.2±8.5) (P>0.05).

Conclusion:

Red wavelength is safe and effective to be used to treat acne vulgaris by LLLT compared to infrared wavelength.

Keywords: Acne vulgaris, clinical trial, low-level laser therapy

Introduction

Acne vulgaris is a very prevalent skin disorder, affecting 35% to over 90% of adolescents and often continuing into adulthood.[1] The disorder is not a serious and contagious situation but affects the patient's social and emotional aspect of life.[2] Current treatments for acne vulgaris include topical and oral medications that counteract microcomedone formation, sebum production, Propionibacterium acnes, and inflammation.[3] These treatments consist of topical antibiotics such as clindamycin and erythromycin, topical retinoids such as tretinoin and adapalene, benzoyl peroxide, alpha hydroxy acids (AHA), salicylic acid, or azaleic acid. In severe cases, systemic antibiotics such as tetracycline and doxycycline, oral retinoides, and some hormones are indicated.[4–7] Currently, there is significant progress in the management of acne vulgaris.

Phototherapy (light, lasers, and photodynamic therapy) was presented as a therapeutic candidate to treat acne vulgaris with low-side effects.[8,9] The use of light source in treatment of acne vulgaris is not new. There are several reports of applying the full spectrum of light to treat acne vulgaris.[10–14] The absorption of light by P. acnes produces phototoxic agents that destroy them.[15,16] It is anticipated that infra red light destruct the sebaceous glands by photo thermal mechanism and reduce acne lesions.[16] Probably red light exerts its action by releasing several cytokines from macrophages and other cells that reduces inflammation.[17]

Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) in the red to near infrared spectral range (630–1000 nm) and nonthermal power (less than 200 mW) has been used in many clinical setting safely.[18–20] In this study, we have used to LLLT at two different wavelengths (red and infrared) as light sources to evaluate their therapeutic effects on acne vulgaris.

Materials and Methods

This study was a single-blind randomized clinical trial. The protocols and informed consent were reviewed and approved by Medical Ethics Board in Iran University of Medical Sciences (IUMS), Tehran, Iran. Participants in this study were patients referred to Dermatologic clinic of Rasol Akram Hospital, Tehran, Iran, and were clinically diagnosed by acne vulgaris between April 2008 and May 2009. Patients with mild to moderate acne vulgaris and age above 18 years participated in this study. Patients were excluded if they have used oral retinoid within past 1 year or any other acne treatment within past 3 months, had any photosensitivity disease, pregnancy, severe acnes that need systemic therapy, or any manipulation of acne.

Informed consent was obtained form participants. Right and left sides of the face were exposed to red LLLT (R-LLLT) and infrared LLLT (IR-LLLT), respectively. The R-LLLT sides were irradiated by InGaAs (630 nm, 10 mW, continuous) (RIKTA, Russia) with fluence 12 J/cm2 and the IR-LLLT sides were illuminated by GaAlAs (890 nm) with fluence 12 J/cm2 twice in week for 12 sessions. All patients were treated by topical clindamycine 2% on both sides.

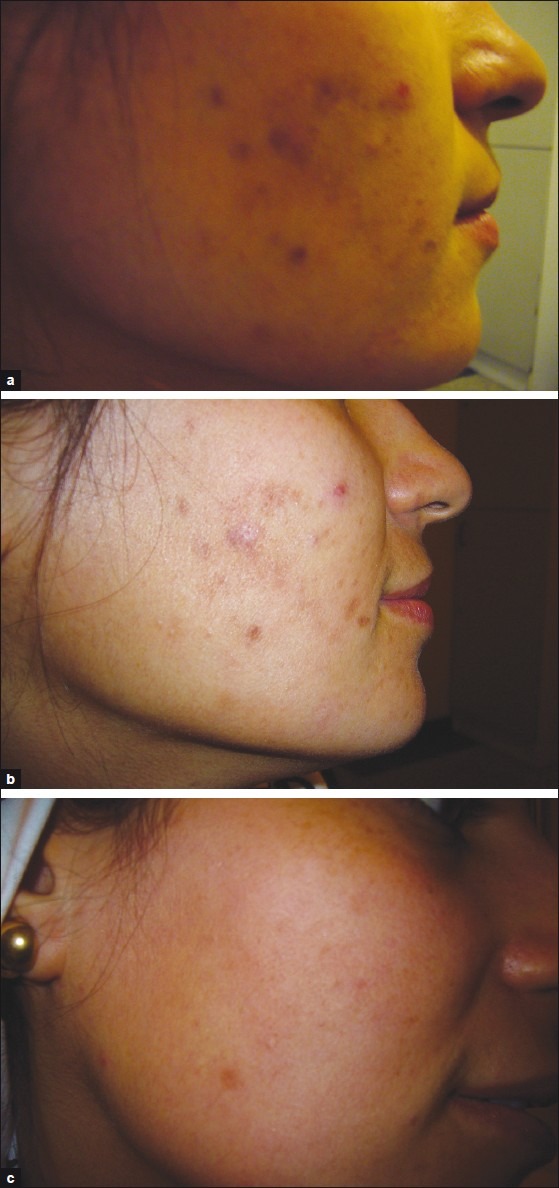

Patients were clinically evaluated at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8. Evaluation was based on formal counts of active lesions (papule and pustule). In addition, facial photographs were taken using a digital camera (PANASONIC, Tokyo, Japan). Photographs were taken using same manner at all time points. The images were viewed by a panel of two dermatologists who were not aware of the treated side.

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Values were tested for normality, and when appropriate a pair sample t-test and independent t-test was used. A P-value of 0.05 or less was considered significant.

Results

All 28 patients (18 women and 10 men) completed the study and none were lost to follow-up or excluded for failure to complete the laser application protocol. All patients tolerated the laser treatment without any adverse effect or reaction. The mean age of the patients was 25.9±2.9 years (range 18–32 years). Fourteen patients had skin type-III and the remained patients had skin type IV.

Total number of lesion of both sides of patients’ face in baseline and each follow-up session was shown in Table 1. There was no significant differences between the mean of lesion counts on the sides treated by R-LLLT and side treated by IR-LLLT (P=0.8). There was a gradual decline in both sides of treated faces during the follow-up, but this trend was more significant in the R-LLLT treated side. Ten weeks after the beginning of treatment, a dramatic decrease in the number of lesion was observed in the R-LLLT treated side [Figure 1].

Table 1.

The mean of total lesion count in two comparative R-LLLT and IR-LLLT study

Figure 1.

Apperance of area treated by red LLLT side at base line (a), after 6 weeks (b), and after 10 weeks (c)

Discussion

Our study showed that LLLT using 630-nm laser (red spectrum) significantly reduces active acne lesions after 12 sessions of treatment during 10 weeks follow-up. There was not any significant reduction of active lesions count in patients treated with 890-nm LLLT. It seems that LLLT in red spectrum is a safe therapeutic modality in treating facial acne vulgaris without any complication.

Despite many approaches to treatment of acne vulgaris, there are many patients who respond inadequately to treatment or experience some adverse effects. Although acne is not a life-threatening disease, but it affects patients’ quality of life and socioeconomic burden. Hence, with all improvements in acne treatment, investigators seek alternative and complementary modalities with more effectiveness and less side effects. Nowadays, phototherapy is an interesting method in management of acne. Exposure of sunlight was used to treat acne and its efficacy has been reported up to 70%.[21] Recently, Wide spectrums of visible lights as phototherapy have been used in treatment of acne. Lasers used as light source in phototherapy release coherent light that can provide very high radiance by focusing on a small targeted area of tissue in contrast to nonlaser light sources.[14,21] Therefore, we used laser source in this study.

Antiacne mechanisms of phototherapy is related to wavelength of light and its chromatophors in the pilosebaceous unit. Generally, these mechanisms include photochemical tissue interactions (without an exogenous photosensitizer) or selective photothermolysis.[16] Photochemical treatment of acne using endogenous porphyrins is based on P. acne photoinactivation.[21]

There are several reports that showed combination of blue and red light could obtain better result than monotherapy with blue light.[22–24] Despite effectiveness of blue light on activation of endogenous P. acnes’ porphyrin, its depth of skin penetration is poor.[25,26]

In comparison with blue light, red spectrum penetrates more deeply in tissue. In addition, it has been shown that red light can affect the sebum secretion of sebaceous glands and keratinocyte behaviors.[27] Red light has less effectiveness on activation of P. acnes’ porphyrin and it does not seem that the beneficial effect of red-LLLT is related to photodynamic reactions. Red light also has antiinflammatory properties through its influence on cytokine production by macrophages.[27]

As per our knowledge, there is only one report about the effect of infrared spectrum of laser in treatment of acne lesions. Paithankar et al. employed a device combining a diode laser at 1450 nm wavelength and cryogen cooling as nonablative manner in the treatment of acne vulgaris.[28] They treated the lesions using a photothermal approach. In this study, we used nonthermal of infrared LLLT to treat the lesions and no significant reduction on the treated side with IR-LLLT was seen. Thus, this modality acts as a placebo for comparison of effect of red light laser in treatment of acne vulgaris.

Our study had some limitation. There was no standard protocol and fluence for LLLT in acne. Therefore, it is possible that the fluence used in this study for infrared LLLT to be inadequate. On the other hand, in this study, patients with severe acne lesion were excluded. Therefore, we are not capable to generalize these finding to all patients with acne vulgaris. Finally, LLLT with red wavelength (630 nm) is a safe and more effective method for treatment of mild to moderate acne vulgaris compared to infrared wavelength (890 nm) and can be combined with its medical treatments.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Stathakis V, Kilkenny M, Marks R. Descriptive epidemiology of acne vulgaris in the community. Australas J Dermatol. 1997;38:115–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1997.tb01126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niemeier V, Kupfer J, Gieler U. Acne vulgaris-psychosomatic aspects. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2006;4:1027–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2006.06110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, Bettoli V, Dréno B, Kang S, Leyden JJ, et al. New insights into the management of acne: An update from the global alliance to improve outcomes in acne group. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(Suppl 5):S1–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merritt B, Burkhart CN, Morrell DS. Use of isotretinoin for acne vulgaris. Pediatr Ann. 2009;38:311–20. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20090512-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramos-e-Silva M, Carneiro SC. Acne vulgaris: Review and guidelines. Dermatol Nurs. 2009;21:63–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elston DM. Topical antibiotics in dermatology: Emerging patterns of resistance. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelly BF, Burroughs M, Mertens M. Clinical inquiries: Does treatment of acne with Retin A and tetracycline cause adverse effects? J Fam Pract. 2004;53:316–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rotunda AM, Bhupathy AR, Rohrer TE. The new age of acne therapy: Light, lasers, and radiofrequency. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2004;6:191–200. doi: 10.1080/14764170410008124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruiz-Esparza J, Gomez JB. Nonablative radiofrequency for active acne vulgaris: The use of deep dermal heat in the treatment of moderate to severe active acne vulgaris (thermotherapy): A report of 22 patients. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:333–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sigurdsson V, Knulst AC, van Weelden H. Phototherapy of acne vulgaris with visible light. Dermatology. 1997;194:256–60. doi: 10.1159/000246114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirsch RJ, Shalita AR. Lasers, light, and acne. Cutis. 2005;71:353–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhardwaj SS, Rohrer TE, Arndt K. Lasers and light therapy for acne vulgaris. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2005;24:107–12. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ammad S, Gonzales M, Edwards C, Finlay AY, Mills C. An assessment of the efficacy of blue light phototherapy in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2008;7:180–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2008.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamilton FL, Car J, Lyons C, Car M, Layton A, Majeed A. Laser and other light therapies for the treatment of acne vulgaris: systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:1273–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lloyd JR, Mirkov M. Selective photothermolysis of the sebaceous glands for acne treatment. Lasers Surg Med. 2002;31:115–20. doi: 10.1002/lsm.10080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guffey JS, Wilborn J. In vitro bactericidal effects of 405-nm and 470-nm blue light. Photomed Laser Surg. 2006;24:684–8. doi: 10.1089/pho.2006.24.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross EV. Optical treatments for acne. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18:253–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2005.05024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Posten W, Wrone DA, Dover JS, Arndt KA, Silapunt S, Alam M. Low-level laser therapy for wound healing: Mechanism and efficacy. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:334–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Djavid GE, Mehrdad R, Ghasemi M, Hasan-Zadeh H, Sotoodeh-Manesh A, Pouryaghoub G. In chronic low back pain, low level laser therapy combined with exercise is more beneficial than exercise alone in the long term: A randomised trial. Aust J Physiother. 2007;53:155–60. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(07)70022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zane C, Capezzera R, Pedretti A, Facchinetti E, Calzavara-Pinton P. Non-invasive diagnostic evaluation of phototherapeutic effects of red light phototherapy of acne vulgaris. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2008;24:244–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2008.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cunliffe WJ, Goulden V. Phototherapy and acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:855–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldberg DJ, Russell BA. Combination blue (415 nm) and red (633 nm) LED phototherapy in the treatment of mild to severe acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2008;8:71–5. doi: 10.1080/14764170600735912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee SY, You CE, Park MY. Blue and red light combination LED phototherapy for acne vulgaris in patients with skin phototype IV. Lasers Surg Med. 2007;39:180–8. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papageorgiou P, Katsambas A, Chu A. Phototherapy with blue (415 nm) and red (660 nm) light in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:973–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noborio R, Nishida E, Kurokawa M, Morita A. A new targeted blue light phototherapy for the treatment of acne. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2007;23:32–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2007.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tzung TY, Wu KH, Huang ML. Blue light phototherapy in the treatment of acne. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2004;20:266–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2004.00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadick NS. Handheld LED array device in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:347–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paithankar DY, Ross EV, Saleh BA, Blair MA, Graham BS. Acne treatment with a 1,450 nm wavelength laser and cryogen spray cooling. Lasers Surg Med. 2002;31:106–14. doi: 10.1002/lsm.10086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]