Abstract

Nurse-led clinics are an increasingly used resource in managing postoperative patients and meeting their clinical needs. Since 2007, St James' University Hospital has run a ward-based nurse-led clinic; providing follow-up and management of patients after thoracic surgery. We aimed to assess patient satisfaction with the clinic's ability to manage their postoperative needs. Data were collected prospectively from patients attending the clinic between July and August 2010 using structured patient questionnaires. We evaluated 83 patient feedback questionnaires. The reasons for clinic attendance were predominantly wound assessment and chest drain review. Fifty-four (65%) patients were managed without seeing a doctor, of whom only four (7%) believed seeing a doctor would have been beneficial. Seventy-three (88%) patients stated their needs were met in the clinic and 82 (99%) patients described the overall care they received as good, very good or excellent. This survey highlights that patients are satisfied with a nurse-led service and will hopefully help encourage the development of such services within thoracic surgery.

Keywords: Nurse-led clinic, Patient satisfaction, Thoracic surgery

INTRODUCTION

The UK government has encouraged the operation of nurse-led clinics since the 1990s in order to meet the increasing multidisciplinary nature of managing health and disease [1]. The aim is to improve the cost efficiency of the outpatients' service, while not compromising the standard of care [1]. This has allowed specially trained nurses to review and manage patients with a certain level of autonomy in an outpatient setting without direct medical supervision in a number of medical and surgical specialties, and studies have demonstrated that they run successfully are safe and cost-efficient [2]. Surgical nurse-led clinics may encourage early discharge and reduce inpatient stay. For example, thoracic surgical patients with a persistent air-leak could be discharged if clinically stable [3] and managed through the nurse-led clinic.

Colorectal surgery is a speciality which has well-established nurse-led clinics [2]. Stoma nurse specialists independently review and manage the stoma care of patients post-surgery. This nurse-led role is a key part of the surgical management of patients undergoing treatment for colorectal cancer in the UK [4, 5].

An outpatient nurse-led clinic was established in the thoracic department at St James's University Hospital in 2007. An experienced and trained senior staff nurse or Sister reviews patients booked into this clinic once a week in a specifically equipped treatment room on the thoracic ward. Patients are requested to attend the clinic by the ward team if at discharge they will require further bedside clinical intervention; for example, patients with a chest drain that will require further review and eventual removal; or the patient who is clinically well with a chest wound that requires further review and dressing change. Patients cannot self-refer to the nurse-led clinic. All post-operative patients are also seen routinely within the consultant clinic at a later date and all patients regardless of follow-up are provided with ward contact details to discuss concerns they may experience at home related to their management.

The clinic nurse manages patients following pre-determined protocols agreed by the consultant team. Clear clinic guidelines are in place concerning common interventions such as chest drain removal, the presence of air leak or volume of fluid draining and when to obtain doctor review. This is usually if there is a complex issue, for example, an air space on chest X-ray post-drain removal, persistent fluid drainage or signs of chest wound infection.

A thoracic ward-based junior doctor is available to review patients or for the nurse to consult if problems arise in the clinic. A senior on-call thoracic surgeon is easily contactable if further review is needed. Patients are offered a 30 min appointment within 7–14 days of discharge. Transport is offered and the patient is provided with the ward contact details to re-arrange the appointment if necessary. This increased flexibility reduces non-attendance, therefore helping to improve overall efficiency of the service.

Our department has previously looked at the safety and cost-effectiveness of this service which demonstrated that the nurse-led clinic led to a decrease in the load of the consultant thoracic outpatient follow-up service, facilitated patient fast-tracking by shortening both waiting times and hospital stay and demonstrated that this type of service is safe and efficient. However, it did not consider patient satisfaction with the care provided. Bearing in mind the growing focus on patient satisfaction with surgical services, we conducted this study to analyse patient opinion and satisfaction with our nurse-led service with the aim of improving the service experience for patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A prospective cross-sectional survey was undertaken in July and August 2010. A specific questionnaire was designed (Fig. 1) and each attendee to the thoracic nurse-led clinic over a 2-month period was asked to complete it anonymously. Patients were asked to assess provision of care by considering various aspects of the process, including appointment queries and ease of appointment re-arrangement. Other factors including overall satisfaction with the service, patient expectation and opinion on being viewed by a nurse rather than a doctor were also addressed. The results were collated and analysed.

Figure 1:

This patient questionnaire was handed out to all clinic attendees to collect patient feedback and opinions.

RESULTS

Patient clinical background

Eighty-five patients in total attended the clinic over the 2-month period and there was a 100% response rate as 85 questionnaires were received back. There were eight clinics with an average of 10 patients attending each clinic. Eighty-three questionnaires were completed fully and used for analysis. Two questionnaires were discarded due to incompleteness. Patients who attended the nurse-led clinic during our study period had previously undergone a variety of surgical procedures (Table 1).

Table 1:

The clinic attendees were comprised of patients with a wide range of initial thoracic problems which required varied surgical management during their inpatient stay

| Reason for initial admission | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| Pleural procedures | Empyema drainage | 15 (18.1%) |

| Pleurx drain insertion | 9 (10.8%) | |

| Thoracic fenestration | 7 (8.4%) | |

| Bedside chest drain insertion for pleural effusion | 6 (7.2%) | |

| Talc pleurodesis | 6 (7.2%) | |

| Decortication for empyema | 2 (2.4%) | |

| CT-guided drainage of pleural space | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Evacuation haemothorax | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Lung resections | Lobectomy | 13 (15.7%) |

| VATS lung biopsy | 5 (6%) | |

| Pulmonary wedge resection | 2 (2.4%) | |

| Bullectomy | 2 (2.4%) | |

| Metastatectomy | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Others | Pectus repair | 7 (8.4%) |

| Chest wall hernia repair | 2 (2.4%) | |

| Radio-frequency ablation | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Conservative management of thorax stab wound | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Unknown | 2 (2.4%) | |

| Total | 83 |

Appointment arrangements

All 83 patients who attended the clinic stated that they found it easy to arrange a convenient appointment and 80 (96%) knew who to contact with a query regarding the appointment or to try and re-arrange it. Nine (11%) patients had rearranged their appointment and all nine stated that they found the process easy and convenient.

Patient management within the clinic

Two main reasons were identified for which patients were required to attend the nurse-led clinic. Forty-three (42%) patients attended for general wound management and 26 (31%) for on-going care and management of a chest drain. Wound management included routine wound inspection, dressing changes and wound swabbing if infection was suspected.

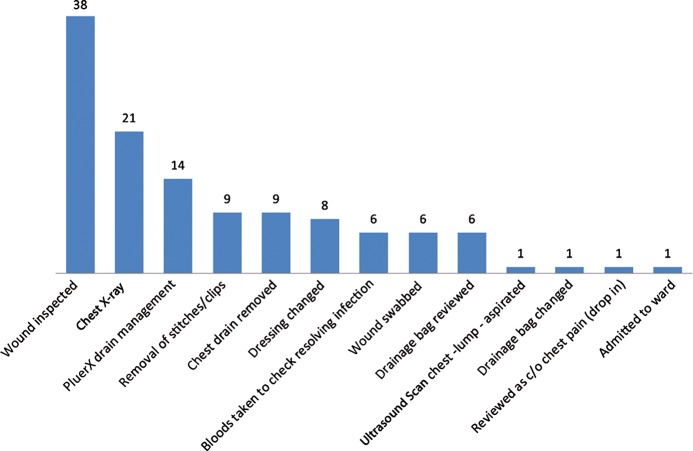

Over the analysis period, a total of 121 patient interventions were performed in the clinic. This can be summarized into 13 discrete interventions (Fig. 2). Some patients underwent more than one intervention.

Figure 2:

The different interventions and the frequency for which they were performed in the nurse-led clinic.

Patient review

From the 83 clinic attendees, 54 (64%) stated that they had expected to see a doctor in the clinic instead of or in addition to a nurse. Of these 54 patients, 19 were actually reviewed by a doctor.

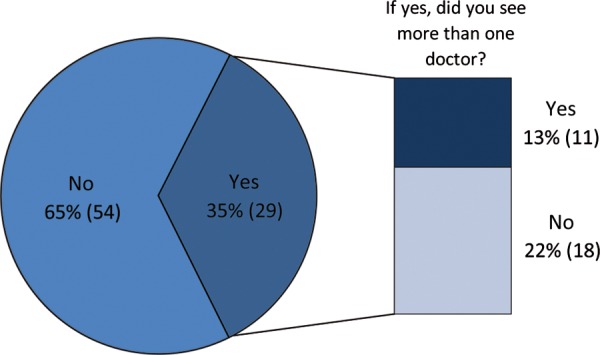

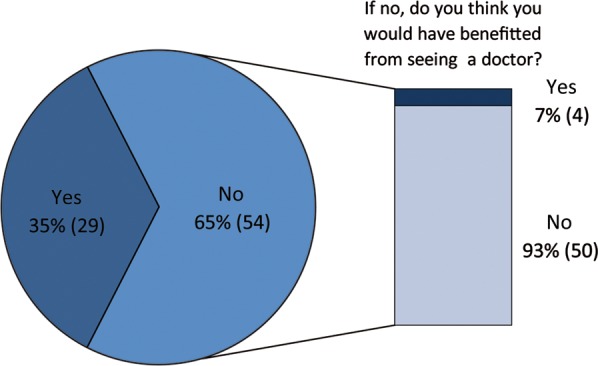

Twenty-nine (35%) patients in total from the 83 clinic attendees were reviewed by a doctor in addition to a nurse and 11 of these saw more than one doctor (Fig. 3.) From the 54 patients who were reviewed by a nurse only, four (7%) of these believed their care would have benefitted from additional doctor review (Fig. 4.)

Figure 3:

The proportion of clinic attendees who were reviewed by a doctor and of these, the attendees who saw more than one doctor.

Figure 4:

The opinions of patients who did not receive doctor review in the clinic revealed that most were satisfied with their management and did not feel they would have benefitted from a doctor review.

In total, 73 (88%) patients believed their needs were met in the nurse-led clinic and regarding their overall satisfaction with the care and management received in the clinic, and 82 (99%) patients described it as either good, very good or excellent (Table 2).

Table 2:

Patients rated their overall satisfaction of their experience in the clinic

| Excellent | 26 (31.3%) |

| Very good | 47 (56.6%) |

| Good | 9 (10.8%) |

| Fair | 1 (1.2%) |

| Poor | 0 (0%) |

DISCUSSION

Nurse-led clinics are a patient-friendly way of reviewing patients. Previously, our patients who needed further bedside clinical intervention or assessment would be reviewed during their consultant outpatient follow-up or as ward attendees. The prospect of a delay in the outpatient clinic or attending a ward with the potential of waiting for a reviewing nurse or doctor to become available are not ideal patient experiences. However, for some surgical specialties, this is still common practice.

Our study demonstrated that overall patient satisfaction with the thoracic nurse-led clinic service is high. A large part of this can be accredited to the ease and familiarity of the process for contacting and attending the nurse-led clinic. Patients attending the clinic are reviewed and managed surroundings they are comfortable in and often by nurses with whom they are familiar, which facilitates a smooth continuation of care for these patients.

This study found that 29 (35%) patients required further review by a doctor during the clinic. Although experienced, the clinic nurses may encounter patients who require a review or intervention beyond the nurse's skill base and this is a limitation to a solely nurse-led clinic. In this study, clear-cut examples of patients requiring doctor review included a patient who required subcutaneous fluid aspiration, one which required clinical assessment due to chest pain and one requiring clinical review due to a pneumothorax. Chest X-ray interpretation performed by a ward doctor was required for 21 patients following drain removal. In some of these cases, clinical review will have been required if an abnormality on chest X-ray was detected. Doctor intervention was also required for difficult venepuncture and for wound inspection if infection was suspected and antibiotic cover required. However, as the clinic is based on the ward, the efficiency of the review process is not compromised. Furthermore, any further investigations could be easily performed and a potential admission easily facilitated if required.

Of the 54 (65%) clinic attendees who were solely managed by the nurse and needed no doctor review, only four patients believed that their care would have benefitted from further doctor review. This further demonstrates that patients were happy with their management and with the proficiency of the healthcare professional who reviewed them in clinic. However, it is still important to ensure that patients are fully aware that the clinic is ‘nurse-led’ by experienced nurses and doctor review is available if clinically indicated.

We accept the main limitation to this study is that patient views and satisfaction were not correlated with their clinical outcomes. For example, if a chest drain removal had resulted in a visible airspace on chest X-ray, this would have required further monitoring or intervention and would have not been an ideal outcome for the patient personally; and this may have influenced that patient's feedback in the questionnaire.

Thoracic nurse-led clinics are much less well established when compared to other surgical specialities such as colorectal surgery. The encouragement and recommended use of nurse-led stoma care clinics within the colorectal cancer care pathway for the management of patients in the UK [4, 5] provides the speciality with a degree of national guidance and more experience to draw upon when developing and implementing new clinic services. National guideline involvement also means there may be improved access to facilities and resources in setting up clinics, compared with our locally developed and managed nurse-led clinic.

This study has touched upon the challenges faced for setting up thoracic surgery nurse-led clinics. There are obvious advantages to the clinic based on or near the department ward such as easy access to doctor review if required and a safe, well-equipped environment for chest drain removal. This may pose a problem for some departments where resources, such as ward space and an extra experienced nurse to run the clinic, may prove difficult to access. The availability of doctor review may cause clinic delays if the ward or on-call doctor is not immediately available for review due to acute inpatient problems or other clinical commitments.

This study was limited to a 2-month data collection period. A longer time period would have provided increased data for the analysis. Some of the patients attending the clinic may attend for further review at a later date. In some cases, this may have been within the 2-month data collection period and therefore the same patient may have filled out a questionnaire on more than one occasion. However, we still feel this is valid as each separate patient experience at the clinic can be judged on its own merit.

CONCLUSION

This survey demonstrates that overall patient satisfaction with the service is high, expectations of care received are in line with actual management and nurse-led clinics are generally positive patient experiences. This study helps to add support for the role of structured nurse-led management in the outpatient care of thoracic surgical patients and will hopefully encourage more to develop.

Our survey results would be enhanced with further work correlating patient satisfaction with clinical outcome. We also suggest comparing patient satisfaction with nurse-led clinic experiences against patient experiences of other types of follow-up such as ward attending, as this may further support for thoracic nurse-led clinics.

From our experience, we can suggest certain prerequisites for starting up a thoracic nurse-led clinic. A suitable clinic location, well equipped for anticipated procedures, is paramount. Clinic proximity to the base ward where extra resources and doctor review may be obtained is important to consider. An experienced nurse whose sole priority is to run the clinic is essential as is the availability of appropriate doctor review, if required. Finally, clear guidelines regarding which patients are reviewed in the clinic and how they are managed need to be developed and agreed between doctor and nursing staff to ensure efficient and safe clinic operation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many thanks to the nurse-led clinic staff at St James' thoracic department for helping to collect the patient feedback questionnaires.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hatchett R. Nurse-led clinics: 10 essential steps to setting up a service. Nurs Times. 2008;104:62–4. 4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Annandale J. How a nurse-led clinic cut outpatient waiting times. Nurs Times. 2008;104:45. 9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varela G, Jiménez M, Novoa N, Aranda J. Estimating hospital costs attributable to prolonged air leak in pulmonary lobectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;27:329–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. Guidelines for the Management of Colorectal Cancer. London: Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network. Management of Colorectal Cancer. Edinburgh: SIGN; 2003. [Google Scholar]