Abstract

Objectives

Parents of newborns and children with special health care needs (CSHCN) often experience conflict between employment and family responsibilities. Family leave benefits such as the federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) and California’s Paid Family Leave Insurance (PFLI) program help employed parents miss work to bond with a newborn or care for an ill child. Use of these benefits, however, is rare among mothers of CSHCN and fathers in general, and limited even among mothers of newborns. We explored barriers to and experiences with leave-taking among parents of newborns and CSHCN.

Methods

We conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews in 2008 with 10 mothers and 10 fathers of newborns and 10 mothers and 10 fathers of CSHCN in Los Angeles to explore their need for and experiences with family leave. Qualitative analytical techniques were used to identify themes in the transcripts.

Results

All parents reported difficulties in accessing and using benefits, including lack of knowledge by employers, complexity of rules and processes, and inadequacy of the benefits themselves. Parents of CSHCN also described being too overwhelmed to rapidly seek and process information in the setting of urgent and often unexpected health crises. Most parents expressed a clear desire for expert guidance and saw hospitals and clinics as potentially important providers.

Conclusions

Even when parents are aware of family leave options, substantial barriers prevent many, especially parents of CSHCN, from learning about or applying for benefits. Clinics and hospitals might be opportune settings to reach vulnerable parents at times of need.

Keywords: family leave, parents, chronic disease, newborn infant

INTRODUCTION

Family leave programs give employees time off work to provide health-related care for family members. Two especially vulnerable categories of family members are newborns and children with special health care needs (CSHCN). Parents of newborns need to bond with their child and manage fatigue and stress associated with parenting.1, 2 Parents of CSHCN need to participate in their child’s health care and provide supervision when the child is ill at home.3–5 Both groups of parents need to manage financial, social, and personal resources to fulfill these needs.4, 6 Parents of newborns or CSHCN are among the most likely to not only miss work but also drop out of the workforce altogether, which can sometimes have damaging effects on family wellbeing.3, 7–9 Formal and informal leave options are designed to help them remain employed and still care for their children.

The 1993 federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) provides up to 12 weeks of family leave with guaranteed benefits and job security, but the leave is unpaid and available only to qualifying employees in large companies and public agencies.10 In 2004, California became the first state to enact the Paid Family Leave Insurance (PFLI) program, which provides up to 55% of salary for up to 6 weeks during family leave.11 Five states (including California) also offer temporary disability insurance (TDI) for mothers unable to work due to pregnancy or delivery.12 Finally, some parents may have access to employer-provided sick leave/vacation, other benefits, or informal leave arrangements.7, 13

Studies have demonstrated potential benefits of family leave. Paid sick leave coverage is associated with more parental care for ill children.14, 15 Longer leave coverage is associated with longer duration of breastfeeding among employed mothers16, 17 and more paternal bonding with infants among employed fathers.8 Parents with access to paid sick leave/vacation are five times as likely to stay home with their sick child as those without.18 Finally, our own research has found that parents believe leave-taking greatly improves child physical and emotional health and, to a lesser degree, parent emotional health.19

Despite existence of various leave options, access to and utilization of family leave is limited.13 A U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) 2000 survey of employees found that only 47% of private-sector employees were covered by FMLA.20 Even use of California’s PFLI, which provides most employees access to family leave, has since its inception been limited mostly to parents with newborns.11 Private employers typically do not fill in the gaps; although 83% of U.S. private-industry workers reported access to employer-provided benefits such as paid sick leave/vacation in 2008, only 8% report access to employer-provided paid family leave.21 Our 2007 study of employed parents of CSHCN found that 40% reported an unmet need for leave in the past year.22

What factors restrict access to and utilization of leave are unclear. Possible factors include limitations of leave benefits (e.g., eligibility, duration, pay), lack of information about options, and concerns about job security, career advancement, or workplace acceptance. In a study of FMLA, 64% of employees who reported needing leave did not take it because it was unpaid, and among those taking leave, about half returned to work early because they could not afford additional time off.23 Our earlier study of employed parents of CSHCN found that only 18% had heard of PFLI and only 5% had used it.24 In a survey of California adults, just 28% knew about PFLI compared to 55% and 69% who knew about FMLA and TDI, respectively.25 Finally, 26% of women and 18% of low-income workers who took leave reported feeling pressure from their employers to return to work.26 How these barriers affect leave-taking decisions of vulnerable parents must be understood before effective interventions can be devised.

In this study, we examined the experiences of parents of newborns or recently hospitalized CSHCN in identifying and using family leave benefits. We compared employed parents of newborns and recently hospitalized CSHCN because both groups involve a vulnerable child requiring continuous care or supervision from an adult. In both cases, short-term work-family decisions may have long-term impacts on both their child’s overall health and their employment. Examining both expected (birth) and unexpected (hospitalization for illness) events allows us to investigate access and utilization of family leave programs through distinct pathways. Moreover, family leave policies (other than maternity and paternity leave) have historically been catchall policies that do not distinguish between the two events. Examining the distinctions, therefore, may have direct policy relevance. Finally, previous studies have surveyed parents about knowledge of leave programs and health benefits for children when taking family leave. However, few studies have inductively explored parents’ experiences of how they respond to work-family conflict in regards to the health of their child.27, 28 Using semi-structured qualitative interviews, we captured detailed experiences with leave-taking and work-family decisions surrounding the care of a child after a birth or hospitalization.

METHODS

Participants and Study Design

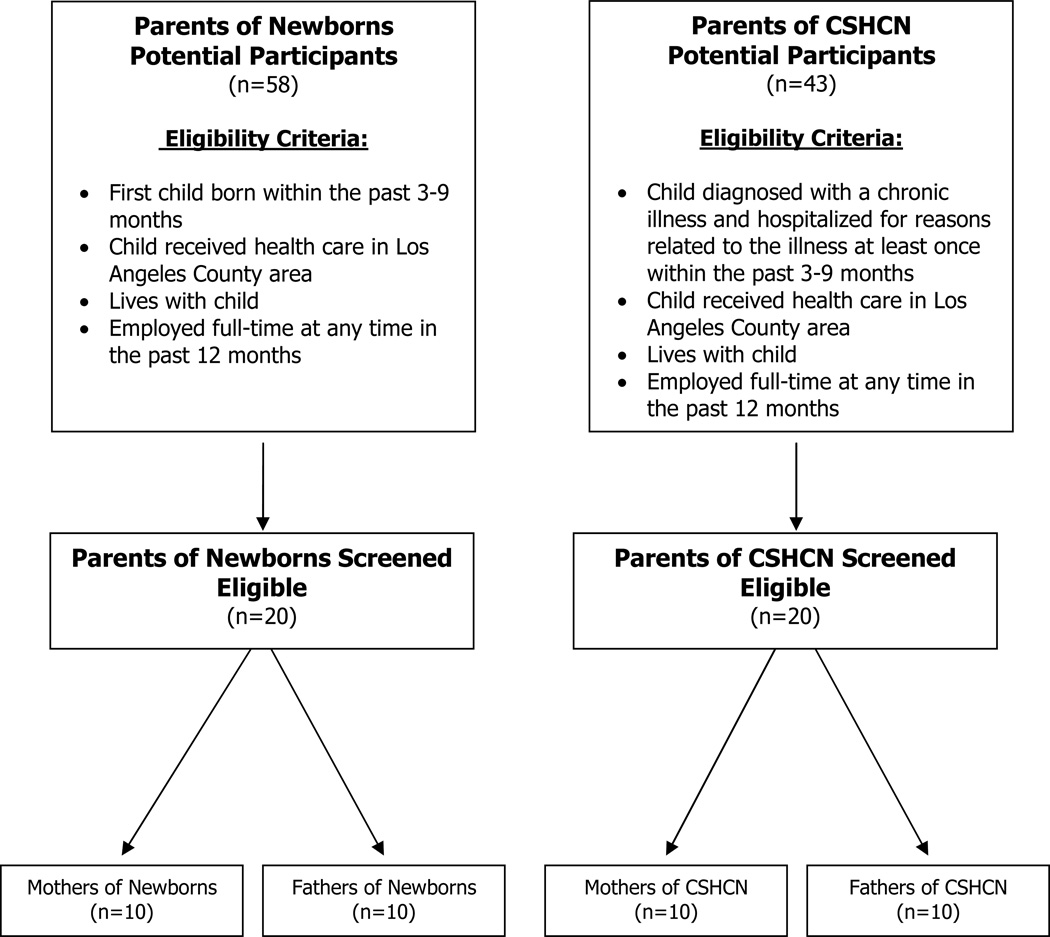

In 2008, we conducted qualitative interviews with a convenience sample of parents of newborns and CSHCN. Potential participants were recruited from UCLA or UCLA-affiliated pediatric outpatient waiting rooms, clinical referrals, and online postings. The primary inclusion criteria were having a first child born or having a CSHCN (ages 0–17) hospitalized in the last 3–9 months, receiving health care for their child in Los Angeles County, living with the child, and being employed full-time (which we defined as at least 25 hours/week, in alignment with FMLA eligibility criteria) at anytime in the past year (Figure 1). CSHCN was defined as having or being at risk for having “a physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional condition” requiring “health or related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally.”29 A validated five-item CSHCN screener was used to identify children who met this definition.29 Two parents whose child qualified as both newborn and CSHCN were placed in the CSHCN parent sample.

Figure 1.

Study Recruitment and Eligibility Flowchart (n=40)

We aimed to interview at least 40 parents (10 mothers of newborns, 10 fathers of newborns, 10 mothers of CSHCN, and 10 fathers of CSHCN), with more if needed to improve the likelihood of valid comparisons between parents of newborns and CSHCN.30 We screened 101 potential participants (58 parents of newborns and 43 parents of CSHCN) to reach our initial sample of 40. Concurrent iterative analyses of notes and transcripts suggested no major new themes emerging, which allowed us to halt recruitment. Each parent was selected from a different family unit. Interviews were conducted in English and Spanish (only one parent requested a Spanish interview). The study received institutional review board approval from RAND and UCLA.

Measures

Interview protocol

A semi-structured protocol was developed to guide the interview in two parts: (1) descriptions of typical days prior to, during, and after the birth or hospitalization of their child; and (2) factors in decision-making regarding whether to take leave from work. For each time point, participants were asked to describe a typical day spent around work, family, and leisure activities. Participants were then asked whether they or their spouse took leave from work. Open-ended follow-up questions were used to explore their experience with identifying and understanding leave options and the factors that influenced their decision whether to take leave from work. We also asked parents to express perceived strengths and shortcomings of family leave benefits available to them through federal, state, and employer-provided options. Interviews were tape-recorded, and lasted about 60 minutes.

Socio-demographic variables

Parents completed a brief survey at the end of the interview. We obtained their gender, age, education, race/ethnicity, marital status, and household income. Parents were also asked whether they had heard about FMLA or PFLI and how much time they had taken off from work to care for their newborn or CSHCN.

Data Analysis

Audiotapes were transcribed and managed with ATLAS.ti. The lone Spanish interview was translated into English after transcription. Content analysis of the narratives was conducted using both inductive and deductive techniques.31 Such analysis allows for a full range of themes and subthemes to emerge, including those that were not anticipated prior to analysis. Following Bernard’s content analysis protocol, we created a set of thematic-based codes, applied the codes systematically to the narratives, and tested the reliability between coders.31 Two trained coders independently coded each transcript, with disagreements between coders resolved by consensus among the first three authors. This procedure produced a body of 857 quotes related to parents’ leave-taking experiences, resulting in four major themes. Cohen’s Kappa was used to check consistency between coders32 and was 0.78–0.92 for all identified themes.33

Although we explicitly compared parents of newborns with parents of CSHCN across all themes, results were often highly similar. Therefore, unless noted otherwise, results are presented without distinction between the groups.

RESULTS

Among the 20 parents of newborns and 20 parents of CSHCN (Table 1), the average age was 35 and the racial/ethnic distribution was 28% Latino and 45% White. Twenty-six parents (65%) had a college degree; 50% reported a household income of >$75,000. Thirty-one parents (78%) had heard of FMLA, and 38% had heard of PFLI. Medical conditions of CSHCN varied widely and included diseases such as asthma, cystic fibrosis, epilepsy, liver failure, and malignancy.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Total Time off Work among Parents of Newborns (n=20) and Parents of Children with Special Health Care Needs (CSHCN) (n=20)

| Demographics | Parents of Newborns | Parents of CSHCN | TOTAL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | # | % | ||

| Mean Age | 34.0 | 36.4 | 35.0 | ||||

| (Age Range) | (22–41) | (19–49) | (19–49) | ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| African American | 3 | 15.0 | 1 | 5.0 | 4 | 10.0 | |

| Asian American | 3 | 15.0 | 3 | 15.0 | 6 | 15.0 | |

| Latino | 4 | 20.0 | 8 | 40.0 | 12 | 30.0 | |

| White | 10 | 50.0 | 8 | 40.0 | 18 | 45.0 | |

| Education Level | |||||||

| High school degree or less | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 10.0 | 2 | 5.0 | |

| Some college | 5 | 25.0 | 7 | 35.0 | 12 | 30.0 | |

| College degree | 5 | 25.0 | 5 | 25.0 | 10 | 25.0 | |

| Graduate school | 10 | 50.0 | 6 | 30.0 | 16 | 40.0 | |

| Household Income* | |||||||

| Less than $30,000 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 15.0 | 3 | 7.5 | |

| $30,001–$50,000 | 5 | 25.0 | 8 | 40.0 | 13 | 32.5 | |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 1 | 5.0 | 2 | 10.0 | 3 | 7.5 | |

| $75,001–$100,000 | 3 | 15.0 | 3 | 15.0 | 6 | 15.0 | |

| Over $100,001 | 11 | 55.0 | 3 | 15.0 | 14 | 35.0 | |

| Family Leave Knowledge | |||||||

| Heard of FMLA | 17 | 85.0 | 14 | 70.0 | 31 | 77.5 | |

| Heard of PFLI | 10 | 50.0 | 5 | 25.0 | 15 | 37.5 | |

|

Parents of Newborns |

Parents of CSHCN |

TOTAL |

|||||

| Mothers | Fathers | Mothers | Fathers | ||||

| Time off from Work | # | # | # | # | |||

| Less than 2 weeks | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 8 | ||

| Between 2 and 6 weeks | 0 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 11 | ||

| Temporarily stopped working for 6 weeks or more |

6 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 13 | ||

| Stopped working | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 8 | ||

One participant declined to report household income

Eight parents took no or minimal leave (<2 weeks). Eleven parents took 2–6 weeks of leave. Thirteen parents took ≥6 weeks before returning, and 8 parents stopped working completely. The vast majority took some combination of vacation or other formal leave (usually sick leave, paid time off, or unpaid FMLA). Several parents of CSHCN also used informal unpaid time off that they arranged with supervisors.

With respect to parents’ leave-taking experiences, four major themes emerged from the interviews: 1) the importance of pre-planning for family leave; 2) difficulties in accessing and understanding information about leave benefits; 3) limitations of the benefits themselves; and 4) the potential importance of help from people who understand what is involved in caring for newborns or CSHCN (i.e., healthcare providers) (Table 2). Themes 2–4 were expressed near-universally and equally strongly by parents of newborns and CSHCN; theme 1, however, exhibited strong differences between parents of newborns and CSHCN.

Table 2.

Overall Study Themes for Leave-Taking by Parents of Newborns and Parents of Children with Special Health Care Needs (CSHCN) (n=40)

| Themes | Parents of Newborn | Parents of CSHCN |

|---|---|---|

|

(1) Importance of pre- planning for family leave |

Reported adequate time to gather and evaluate family leave options; proactive |

Reported lack of time to plan, gather, or evaluate family leave options; reactive |

|

(2) Difficulties in accessing and understanding information about family leave benefits |

Used multiple sources to gather information; cited employers as influential but often unhelpful Information about eligibility and benefits was difficult to understand |

Used multiple sources to gather information; cited employers, family, and friends, all of whom were often unhelpful Information about eligibility and benefits was difficult to understand, especially given lack of time |

|

(3) Limitations of family leave benefits |

Limited benefit eligibility (e.g., length of time with employer, company size) Limited benefit provision (e.g., job protection, pay) |

Limited benefit eligibility (e.g., length of time with employer, company size) Limited benefit provision (e.g., job protection, pay) |

|

(4) Potential importance of people who understand what is involved in caring for newborns or CSHCN (i.e., healthcare providers) in helping navigate these barriers |

Need for more accurate information in lay language Preference for information from advocates who understand newborn needs |

Need for more accurate and timely information in lay language Preference for timely information from advocates who understand CSHCN needs |

Pre-Planning for Leave Is Critical

Parents universally expressed an enormous, often distressed, sense of need for family leave. One mother of a two-year-old child with a brain tumor described her initial situation:

“When we first realized that [our child] had a serious illness…he was in the hospital that day. And physically I was in the hospital and I was having to make a lot of phone calls and I was very worried. I was either on the phone with work or on the phone with my family and talked to a bunch of different people: social workers, doctors, nurses…It was kind of a blur…We didn’t want to leave him [in the hospital] alone for fear that he wouldn’t get the right care or he’d be afraid or it would compromise his emotional wellbeing or physical well-being…I had to make arrangements with my work…And then once I had that hammered out with my boss—what days I would be working or staying with him at the hospital…Emotionally, we wanted to both be at the hospital at all times and just not work, but that wasn’t an option. We knew if we’d do that we would lose our house and we would lose our job and we lose our health insurance so that just wasn’t feasible.

Despite sharing this need for taking time off work to care for their child, parents of newborns and CSHCN differed substantially in their ability to plan for and successfully access leave. Parents of newborns generally felt that they had adequate time to gather and evaluate information prior to the birth of their child. One new mother reported “Before N was born, I read a lot about my company’s policies…So I was ready to either stay home or go back to work.” Another new mother explained her plans:

“I knew I wasn’t going to be ready to go back to work after 6 weeks. So when I found out about…Paid Family Leave, that was a relief because then I knew that I could stay with him another 6 weeks and still sort of get paid for it.”

Parents of CSHCN, because of the relative unexpectedness of their child’s illness and/or hospitalization, were far more reactive. One mother whose son was newly diagnosed with lymphoma described her experience:

“In the hospital, just 24 hours of non-stop [being] awakened by the nurses or taking care of him, or just dealing with doctors…It took a week to find out what he had…[The doctors] explained to us the length of hospital stays and what our life is gonna be like. At that time I just made the decision not to go to work.”

A father discussed initially trying to balance work with his son’s new and unexpected respiratory illness:

“He was in the hospital for 4 weeks. I had to go back to work, I was spending 3 weeks at work and I was trying to figure out a way…I would go to work, come home, go to the hospital.”

Information about Leave Is Difficult to Access and Understand

Despite these differences in the time available to pre-plan, parents of newborns and CSHCN expressed similar methods of, and frustrations with, obtaining information about family leave. Both reported using multiple sources to obtain information, including family and friends, websites, and pamphlets. Healthcare providers were almost never mentioned as sources. Employers, however, were generally seen by parents of newborns as having the greatest initial influence on their ability to obtain information. One mother of a newborn echoed comments of many parents on the lack of helpful advice she received at work:

“Even though I worked for a department of social services…They never sat down and said, ‘Well, how much time are you taking off?’ They never said, ‘Well, these are your options.’”

Overall, about half of parents of newborns and about a quarter of parents of CSHCN were aware of PFLI. Even when aware of PFLI, parents reported difficulty comprehending eligibility criteria and options for family leave. One mother of a CSHCN described how the lack of understanding exacerbated the urgency of her situation:

“Paid Family Leave was very complicated to understand…Nobody had a really clear picture of it even at the human resources office…I have to admit I didn’t understand it…But I really didn’t have the luxury of time to study it all.”

A father of a newborn described how each detail added another layer of complexity, especially with respect to how federal and state programs meshed with employer-provided benefits:

“The…thing that was confusing—in terms of [PFLI]…you can take it intermittently. So it wasn’t quite clear how that system worked and how that would work with both the state and how an employer might handle that.”

Limitations in Leave Benefits Make Leave-Taking Even Harder

Even when benefits were understood, parents of newborns and CSHCN perceived inadequacies in the benefits themselves. A few parents reported not qualifying for FMLA because they had not been employed for 12 months or had not worked enough hours (FMLA requires a minimum of 1,250 hours in the past year). A father of a CSHCN commented:

“You have to be with the job for 12 months…I could understand how if you started a job and a month later you asked for Family Leave, there [are] grounds there for you not to have your job back. But if you’re with the company 9 months, 10 months, 11 months like I was, I believe that there should be a little bit more leniency on the company’s behalf.”

More frequently, though, parents complained about inadequacy of financial coverage, not only with FMLA (which is unpaid) but even with PFLI (which provides up to 55% salary for up to 6 weeks). One mother of a CSHCN expressed her frustrations: “6 weeks of [PFLI]…wouldn’t be enough to pay for groceries, daycare, and your mortgage and if you have a car payment, or to pay your bills and feed your children.”

Information from Healthcare Providers Could Have Made a Difference

Both parents of newborns and CSHCN expressed a need for higher-quality information about family leave, with parents of CSHCN frequently emphasizing the urgency of such information. One mother of a CSHCN described the importance of obtaining timely information from her employer: “If they would have given me more information on the FMLA leave, or if they would have given me more information on their procedures, protocol of leaving [work] in case of an emergency situation, it would have benefited my decision more.”

Personalized, hands-on, often hospital- or clinic-based help was the most commonly desired avenue for increasing awareness and informed decision-making. A mother of a CSHCN commented that having someone at the hospital who understood how child illness, specifically, affected parents would have been most useful:

“I think the financial implications of having a child that is ill is not something you really ever think about. And how it changes your work-life and the jobs you take and what you do…I’m wondering, ‘What are my other options?’ I mean maybe there are other options, but I don’t know. It’d be nice to have someone help us work through all of that…”

Another mother of a CSHCN, echoing other parents, wished that she had a personal advocate at the hospital (e.g., social worker, clinician) “who knows the laws and knows what to do and how to help you make your life not so stressful, stressing over a child.”

Lack of Leave-Taking Options Restricts Parent Decision-Making

Hampered by lack of time, information, benefits, and/or guidance, parents made decisions they often deemed unsatisfactory and sometimes found unsustainable. A single mother of a newborn explained how she needed more time off to be at home with her baby yet returned to work to keep her job:

Being a new employee I was supposed to be back after 6 weeks. But I just became very adamant after bonding with him and, because he was a preemie…I had changed and made a decision that I was going to stay home a lot longer…[But] they don’t offer those options…So, yeah, it’s pretty much Monday through Friday 40 hours a week.

A mother of a CSHCN discussed how her decision to continue working required intensive scheduling to cover childcare and job responsibilities:

“There’s just this kind of constant, until things settle down, constant juggling act…We wanted [my child] to receive the best care as possible and I knew that meant that we had to keep our insurance and I had to keep my job. So, that pretty much drove the decision that [my partner] would stay with him at certain times and I would be at work…We had this big spreadsheet that we would plug in who was gonna be where…We had to space everything out and make sure everybody was to maximize his coverage [to create] the least amount of work disruption for us.”

A father of a newborn reflected on his insoluble conflict between family and work responsibilities:

I want to give myself as much time as possible, because I knew [my spouse] was going to be fragile, and she was going to need all the help she could get. I was thinking I need to take as much time as possible off of work without them getting too upset about it…Two months was too much time though, because, like I said, I’m in a management position…And then 2 weeks off, I felt like that’s just not gonna work because I’m not gonna be able to contribute in any way I want to within those 2 weeks…

Echoing other parents, a single father of a CSHCN describes a situation in which his choices ultimately vanished:

The thing that’s probably changed the most for my work environment has been just scheduling my work around her illness and just trying to be with her as much as possible…And my boss is…very accommodating, but he also knows, too, that I have certain responsibilities that I have to fulfill…There really is no other option.

DISCUSSION

Family leave benefits provide an opportunity for parents of newborns and CSHCN to balance employment and family needs. Without such programs and other work-family benefits, parents may be more likely to be forced into decisions that jeopardize their employment or their child’s health. This exploratory study offers insights on parents’ needs as they access information on leave options and make decisions about leave-taking. We captured key barriers hindering use of leave benefits and identified potential ways to address these barriers in future interventions and policies.

Parents of both newborns and CSHCN reported problems accessing and understanding information about leave benefits, and dealing with program limitations. Consistent with prior studies,22, 24 many California parents were simply unaware of PFLI and other leave options. Poor access to information was most often attributed to a lack of expertise among employers and the failure of alternative information sources, including publicly available materials and social networks, to compensate. For many parents who were aware of their leave options, the lack of full financial coverage and/or job protection were barriers to taking family leave—even parents who were more financially well-off expressed concerns about losing their job or being unable to pay expenses.

A key difference exists, however, between parents of newborns and CSHCN—the ability (or lack thereof) to plan for their work/family needs in advance. For most parents of newborns, several months of advanced warning provided an opportunity to make more informed decisions about family leave. For parents of newly diagnosed or acutely ill CSHCN, the relative unexpectedness of their child’s hospitalization dramatically shortened the time available to obtain and understand leave information. Their inability to confidently predict the requirements and duration of their child’s illness episode posed additional challenges. Finally, their immediate concern about their child’s ill health often overwhelmed other concerns. Reduced ability to make informed decisions about employment and leave-taking may in part explain the increased risk of job loss and other negative outcomes reported among these parents.19, 22 Although few parents in this study appeared ineligible for federal and/or state benefits, the timing and confusion rendered many parents’ eligibility relatively meaningless. Despite often not knowing about the availability of various leave options or their eligibility for these programs., many parents acted by default as if they were ineligible in order to avoid the time and stress of pursuing these benefits while emotionally distressed.

Even with our aim of examining leave-taking experiences from two distinct groups of parents (parents of newborns and CSHCN), our findings revealed more similarities than differences, similarities that seemed also to transcend demographic differences. However, these findings may not be generalizable to all employed parents of newborns and CSHCN. First, selection bias of parents who agreed to participate in this study may limit the applicability of our findings to all parents. Parents were recruited from a single area, and thus these findings may not apply to parents in other regions or states. Second, the sample for this study is limited to a convenience sample, and represents parents that tend to be more educated and have higher household incomes than typical parents. How these characteristics might bias results is unclear—more educated parents, for instance, might have greater job flexibility but less substitutable job responsibilities; similarly, parents with lower-status (i.e., non-salaried) jobs tend to be more aware of PFLI, possibly due to greater union involvement.24 Furthermore, parents with lower household incomes may be less likely to take time off due to financial needs.

Parents’ recommendations for improving family leave programs were often expressed within two contexts: (1) better delivery of information from employers/human resources departments/government agencies and (2) instrumental and informational support from clinicians or social workers in the clinic/hospital setting. The second recommendation has clear clinical implications. Clinical personnel may serve as a potentially valuable information source for work-family benefits,34 especially through multidisciplinary coordination among clinicians, social workers, and discharge planners that addresses employment and family leave options.

Finally, as state and federal policy makers continue to debate and develop family leave programs, they should consider not only the ways in which policies may need to be responsive to the needs of specific populations, but also the need for efficient and effective dissemination in a variety of clinical situations. Policies may need to mandate robust dissemination of information by employers and governments, decouple parental leave for birth or adoption from family leave for illnesses, and provide fast-track application procedures aimed specifically at employees whose family members experience sudden, unexpected, or serious illnesses. Those who design or administer policies and dissemination strategies must distinguish between a newborn’s birth and a child’s hospitalization and recognize the unique challenges of each. Successful refinement and implementation of family leave policies, therefore, may require not only educating clinicians to help them disseminate information but also incorporating their frontline expertise into the policy process.

What’s New.

Employed parents of newborns or CSHCN experience both enormous need for leave and enormous barriers to leave-taking related to lack of time, information, benefits, and guidance. Parents view healthcare providers as potentially key sources of support.

Acknowledgments

Research Support: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 5K23HD050517 (PI: Chung), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 5U48DP001934 (PI: Bastani)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Troy N, Dalgas-Pelish P. The natural evolution of postpartum fatigue among a group of primiparous women. Clin Nurs Res. 1997;6(2):126–139. doi: 10.1177/105477389700600202. discussion 139–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pruett K. Role of the father. Pediatrics. 1998;102(5 Suppl E):1253–1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okumura M, Van Cleave J, Gnanasekaran S, Houtrow A. Understanding factors associated with work loss for families caring for CSHCN. Pediatrics. 2009;124(Suppl 4):S392–S398. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1255J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg S, Morris P, Simmons R, Fowler R, Levison H. Chronic illness in infancy and parenting stress: a comparison of three groups of parents. J Pediatr Psychol. 1990;15(3):347–358. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/15.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leonard B, Brust J, Nelson R. Parental distress: caring for medically fragile children at home. J Pediatr Nurs. 1993;8(1):22–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedrich W, Friedrich W. Psychosocial assets of parents of handicapped and nonhandicapped children. Am J Ment Defic. 1981;85(5):551–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perrin JM, Fluet CF, Honberg L, Anderson B, Wells N, Epstein S, et al. Benefits for employees with children with special needs: findings from the collaborative employee benefit study. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2007;26(4):1096–1103. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldman R, Sussman AL, Zigler E. Parental leave and work adaptation at the transition to parenthood: Individual, marital, and social correlates. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2004;25(4):459–479. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han WJ, Ruhn C, Waldfogel J. Parental leave policies and parents' employment and leave-taking. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2009;28(1):29–54. doi: 10.1002/pam.20398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waldfogel J. The Impact of the Family and Medical Leave Act. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 1999;18(2):281–302. [Google Scholar]

- 11.State of California, Employment Development Department. [Accessed March 11, 2010];Paid Family Leave. http://www.edd.ca.gov/Disability/Paid_Family_Leave.htm. Published 2010.

- 12.Guendelman S, Pearl M, Graham S, Hubbard A, Hosang N, Kharrazi M. Maternity Leave in the Ninth Month of Pregnancy and Birth Outcomes among Working Women. Womens Health Issues. 2009;19(1):30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman DE. Employer supports for parents with young children. Future of Children. 2001;11(1):63–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clemans-Cope L, Perry CD, Kenney GM, Pelletier JE, Pantell MS. Access to and use of paid sick leave among low-income families with children. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):E480–E486. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heymann SJ, Earle A, Egleston B. Parental availability for the care of sick children. Pediatrics. 1996;98(2 Pt 1):226–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guendelman S, Kosa J, Pearl M, Graham S, Goodman J, Kharrazi M. Juggling work and breastfeeding: effects of maternity leave and occupational characteristics. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):e38–e46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berger L, Hill J, Waldfogel J. Maternity leave, early maternal employment and child health and development in the US. Economic Journal. 2005:F29–F47. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heymann J. Forgotten Families: Ending the Growing Crisis Confronting Children and Working Parents in the Global Economy. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schuster MA, Chung PJ, Elliott MN, Garfield CF, Vestal KD, Klein DJ. Perceived Effects of Leave From Work and the Role of Paid Leave Among Parents of Children With Special Health Care Needs. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(4):698–705. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.138313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waldfogel J. Family and Medical Leave: Evidence from the 2000 Surveys. Monthly Labor Review. 2001 Sep;:17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diaz IS, Wallick R. Leisure and illness leave: estimating benefits in combination. Washington DC: Office of Compensation and Working Conditions, Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung PJ, Garfield CF, Elliott MN, Carey C, Eriksson C, Schuster MA. Need for and use of family leave among parents of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2007;119(5):E1047–E1055. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerstel N, McGonagle K. Job Leaves and the Limits of the Family and Medical Leave Act: The Effects of Gender, Race, and Family. Work and Occupations. 1999;26(4) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schuster MA, Chung PJ, Elliott MN, Garfield CF, Vestal KD, Klein DJ. Awareness and use of California's paid family leave insurance among parents of chronically ill children. JAMA. 2008;300(9):1047–1055. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.9.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milkman R. New Data on Paid Family Leave. Los Angeles, CA: California Family Leave Research Project, UCLA Institute for Research on Labor and Employment; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milkman R, Appelbaum E. Paid Family Leave in California: New Research Findings. Los Angeles: State of California Labor; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenzweig JM, Brennan EM, Ogilvie AM. Work-family fit: Voices of parents of children with emotional and behavioral disorders. Social Work. 2002;47(4):415–424. doi: 10.1093/sw/47.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ba S. Meaning and Structure in the Work and Family Interface. Sociological Research Online. 2010;15(3):12. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bethell C, Read D, Stein R, Blumberg S, Wells N, Newacheck P. Identifying children with special health care needs: Development and evaluation of a short screening instrument. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2002;2(1):38–48. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2002)002<0038:icwshc>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How Many Interviews Are Enough?: An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernard HR. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 4th ed. Lanham, Md.: AltaMira Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen J. Coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landis J, Koch G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garfield C, Pickett K, Chung P, Lantos J. Who cares for the children? Pediatricians and parental leave. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;3(5):228–233. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2003)003<0228:wcftcp>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]