Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate whether this new method is clinically applicable after theoretical and cadaver testing.

Methods

The incidence of spinal metastases requiring therapy is increasing, due to enhanced life expectancy. Due to results from studies with epidural compression a combined surgical and radiation therapy is often chosen. Minimal invasive cement augmentation is an increasingly used technique, due to fast pain relief and immediate stabilisation. On the other hand, stereotactic radiosurgery is considered to provide a more durable response and better local disease control than conventional radiotherapy with the application of higher doses. Therefore the combination of cement stabilisation and simultaneous intra-operative radiation with immediate stabilisation and high-dose radiation could be an interesting therapeutic option. The results of a clinical feasibility study are presented.

Results

17 patients could be treated with the new method. In two patients (10%) intra-operative radiation could not be applied. No surgical interventions for complications were required.

Conclusions

Summarizing Kypho-IORT is technically feasible with an intra-operative risk profile comparable to sole kyphoplasty and a shorter treatment time and hospitalisation for the patients compared to conventional multifraction radiation. Radiation could not be applied in 10% of cases due to technical difficulties. The results of this feasibility study permit further evaluation of this new technique by a dose escalation study which is currently in preparation.

Introduction

The skeletal system is the third most frequent location for metastases, with the leading focus in the spinal column [1–3]. In addition, the general rate of spinal metastases requiring therapy is increasing due to enhanced survival rates by new therapeutic regimes [4]. Radiation was long considered the main choice of therapy, which was due to studies finding no difference between laminectomy without stabilization versus radiotherapy [5, 6]. Recent studies of spinal metastases with epidural compression showed better results for a combination of metastasis resection with stabilization and adjuvant radiotherapy [7, 8]. For patients without epidural compression but with pain, pathologic fractures, existing or impending instability, the treatment options include radiotherapy, analgesics, bracing and surgery. Although radiotherapy is frequently used, pain relief may take weeks and restabilization months, if it occurs at all. In these patients less invasive techniques such as kypho- or vertebroplasty with immediate stabilization and faster pain relief, combined with short surgical times and low morbidity, have shown their effectiveness for stabilization, prevention of further deformity and pain reduction in several studies [9–13]. Furthermore, not only have surgical improvements occurred but there have also been improvements in radiotherapy. Stereotactic radiosurgery has the potential for high-doses in one to five fractions, with single fraction doses as high as 24 Gy [14]. Although the data is not finally conclusive, it seems that radiosurgery with its higher doses could show benefits over conventional radiotherapy with a more durable response and local control independent of tumour histology [15–18]. However, as in conventional radiotherapy, pain decrease usually takes weeks [19] and the potential for fractures despite high-dose radiosurgery exists in up to 39% of cases [20]. Against this background, combining cement stabilization with its immediate effect and fast pain relief with simultaneous intra-operative radiation and its potential for high-dose could be an interesting therapeutic option. We therefore established the technical requirements for a combined kyphoplasty and intra-operative radiation therapy (Kypho-IORT). After thorough theoretical and cadaver studies [21] a clinical feasibility study was conducted prior to the planning of a long-term outcome study. The results of this clinical feasability study are presented here.

Material and methods

The development of a combined kyphoplasty/radiation procedure was established by an interdisciplinary approach by orthopedic and trauma surgeons, radiation oncologists and technicians from industrial partners. The procedure of balloon-kyphoplasty (Medtronic, Kyphon, Minnesota, USA) is already proven and was used as basis. The requirements for the radiation source were easy mobility for application in the operating room (OR), small dimensions which allow a direct application in the vertebral body and a steep decrease of radiation to allow a high local dose application without negative side effects on adjacent tissues, primarily the spinal cord. These preconditions were found in a commercially available source (Intrabeam®, Carl Zeiss AG, Germany, Fig. 1). The Intrabeam® source produces low energy X-ray (30–50 kV). Electrons strike a gold target at the end of a 10-cm drift tube, producing braking radiation similar to a point source with a steep dose decrease (Fig. 2). Based on the dimensions of the Intrabeam® and the kyphoplasty instruments a way for a combined application was developed by the use of an applicator for the drift tube and two metal sleeves (Fig. 3). The length of the sleeves is given by the dimensions of the drift tube of the Intrabeam® and the working cannula of the kyphoplasty set. The first steps are identical to a standard kyphoplasty: after application of the k-wire, the working cannula is equipped with the two sleeves and inserted into the vertebral body, with one metal sleeve positioned in the pedicle. After removing the working cannula, a hole is made by the use of a burr with the aim of allowing a central position of the apex of the drift tube in the vertebral body. The central position is needed for an equal distribution of the radiation and to avoid damage to the tip of the applicator. The working cannula is removed and the drift tube of the Intrabeam® is inserted over the metal sleeve (Figs. 4 and 5). After application of the radiation the drift tube is removed and the working cannula is inserted again while the metal sleeve remains in place to avoid reflow of the cement. The rest of the procedure is a standard kyphoplasty with inflation of the balloon followed by cement application. Once the technical requirements were understood, a calculation and cadaver study was performed [21]. The results were evaluated by the local ethics committee and the Federal Office for Radiation Protection, which gave permission for the study in a standard operating room without specific radiation protection requirements, due to the steep dose decrease with practically no radiation at the body surface. A single dose of 8 Gy at 5 mm was chosen, as this was found in studies to be equally successful compared with multifraction radiotherapy regarding pain control and spinal cord damage [22]. The general indication for radiation was set by the department of radiation oncology according to established criteria. In symptomatic patients up to three lesions without epidural compression or neurologic deficit were considered. The patient's consent for the new method was required after being thoroughly informed. Surgical criteria were an adequate bony border to allow for a safe cement application, no severe deformity requiring open reconstruction, no extreme adiposity which could lead to problems with the length of the metal sleeve and visibility of pedicle margins by fluoroscopy, usually leading to exclusion of metastases above T3. If these requirements were fulfilled the final indication for Kypho-IORT was always made as a single case decision by means of an interdisciplinary setting.

Fig. 1.

Intrabeam® radiation source on mobile platform with flexible arm

Fig. 2.

Schematic drawing of the radiation source with drift tube (with permission from Carl Zeiss AG, Germany)

Fig. 3.

Applicator for drift tube (top), two metal sleeves (middle) and standard working cannula for kyphoplasty (bottom)

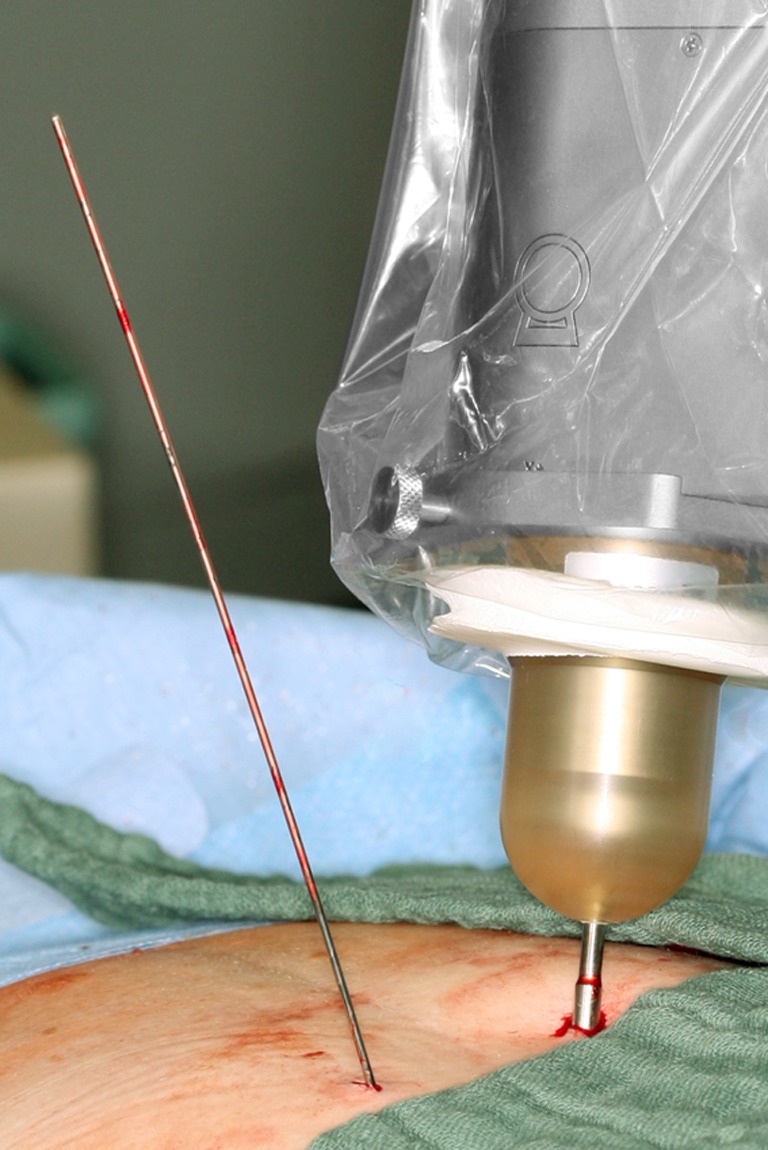

Fig. 4.

Insertion of the radiation source with applicator into the metal sleeve

Fig. 5.

Applicator of radiation source positioned in metal sleeve (right) and k-wire from bipedicular approach (left)

Results

Seventeen patients (seven male, ten female) with an average age of 63.4 ± 7.7 years were included in this pilot study. Tumor entities were eight breast, two lung and prostate and one liver, rectum, colon, gastric and ovarian cancer. Twenty vertebral bodies were treated, one T3, two T5, one T6, two T7, one T8, two T9, one T10, two T11, two T12, three L1, two L2, and one L3. The average surgical time was 81 ± 28 minutes, of which about two minutes were for the application of radiation. The time for one vertebral body was 69 minutes, when dividing the overall surgical time by the number of vertebral bodies treated. Intra-operatively no specific complications requiring additional medical or surgical interventions occurred. In some cases cement leakage was seen, all of which was clinically asymptomatic. In one case bending of the drift tube occurred. As damage to the radiation source could not be excluded immediately, radiation was not performed. In another case the radiation source could not be applied accurately so the safety system of the Intrabeam at the apex did not allow initializing radiation. Overall in 18 of 20 vertebrae (90%), radiation could be applied as planned. In the immediate postoperative period no radiation related complications occurred. VAS back pain decreased from pre-operative 4.9 ± 2.3 to 2.9 ± 2.1 on the first postoperative day.

Discussion

The combination of kyphoplasty and intra-operative radiation has theoretical benefits in the treatment of spinal metastases by combining immediate stabilization and fast pain relief with high local radiation doses. The developed instruments and technique was shown to be effective in our study. The risk profile was comparable to cement augmentation for osteoporotic fractures, which is mainly characterized by asymptomatic cement leakage. Although leakage can lead to severe sequelae such as symptomatic pulmonary cement embolism or even paraplegia, the overall risk is rated as low [13]. The procedure is minimally invasive and can therefore be applied to cancer patients with reduced general health, where radical surgery is contraindicated. Pain relief after cement augmentation usually occurs early, as in our patients typically on day one. The reduction from VAS from around five to three in our study however is not huge. It must be kept in mind that these are the one-day values and that further reduction of pain over time can be expected, as occurs in kyphoplasty over the initial weeks. Kyphoplasty also recently showed a benefit over conservative management in cancer patients in a randomised study [23]. The effect over time can be further enhanced by the additional pain relief due to the radiation. Other reasons are that patients with advanced stages of tumor disease are usually under treatment with pain medication leading to lower initial VAS scores. Also postoperatively there are multiple reasons for restrictions in well-being scores. Nevertheless, the early pain relief within a day is a definite advantage compared to radiation alone, where it usually occurs within weeks and only occasionally within days [19]. The low risk profile short-term, fast pain relief and the single fraction radiation shortens therapy time and hospitalisation, which has a high priority as many of these patients have and will have multiple in-patient treatments in the course of their disease. This can lead to improved patients acceptance of the therapy, although this is only a side effect and not the main reason for this new technique.

In two of our patients radiation could not be applied. This occurred in the first cases and after further technical modifications we did not see this problem again. Nonetheless, theoretically this problem could occur in the future as well, but there is always the back-up option of percutaneous radiotherapy. No patient is therefore deprived of optimal therapy even in case of a failure of the intra-operative radiation. We believe, this back-up option can be considered an important safety measure. Nevertheless, these cases also show that the technique has a learning curve, as do all new developments. For surgeons familiar with cement augmentation and its pitfalls it is all equally easy to implement from a technical point. External preconditions are relatively low, as beside the need for a commercial kyphoplasty and radiation equipment, no specific constructional modifications are needed. In the context of back-up options one must also consider local failure by recurrent or progressive metastases. In these cases it seems possible to change the surgical strategy to circumferential resection and reconstruction, as demonstrated for cement augmentation in osteoporotic cases [24]. In case of adjacent segment metastases an additional Kypho-IORT seems feasible without radiation damage due to the steep dose decrease and limited radiation field.

As no long-term studies have been performed, indications for Kypho-IORT were actually made by the need for radiation in combination with pain and pathologic fracture. Another potential indication is prophylactic stabilization due to impending instability. Although several studies tried to define objective criteria these are still not clear. They are mainly osteolysis over 40–50% of the vertebral body or three column disease are considered to be potentially instable. These patients are thought to have an indication for radiation. Despite the potential effect of restabilization of vertebral bodies after radiation, consecutive fractures are not rare. Rose et al. [20] found, in 39% of the vertebral bodies treated by single fraction radiation with doses from 18–24 Gy, a new or progressive fracture developed despite the fact that besides lytic lesions there are also sclerotic and mixed lesions involved. If only lytic lesions were considered with occupation of the vertebral body of 41–80%, 11 of 13 patients (85%) had fracture progression. Based on the findings by Rose et al. [20], patients with osteolytic lesions of >40% or a lesion above T10 could be candidates for prophylactic stabilization, preferably by minimally invasive cement augmentation. Schneider et al. [21], based on similar assumptions, calculated a potential of 34% of patients with spinal metastases eligible for Kypho-IORT. As more patients will experience spinal metastasis due to higher life expectancy in metastatic cancer, it seems likely that the significance of Kypho-IORT in spinal metastases could increase. Whether a prophylactic indication in asymptomatic patients in the future is worthwhile can only be answered after determining predictive parameters for a beneficial outcome.

A specific drawback of the technique is that the metal sleeve has currently a fixed length (6 cm), which can lead to problems in obese patients, so that a treatment cannot be performed. The possibility can be determined by pre-operative measurement of the distance from skin to the end of the pedicle in CT or MRI.

However, the major drawback by now is that the theoretical benefits must be clinically proven. The primary point here is whether a safe application of local high doses without short- or long-term toxicity is possible and whether this leads to an equal or better local disease control than conventional radiotherapy. Secondary points are pain relief, quality of life and fracture prevention compared to radiation alone. In order to be able to answer the safety point, a long-term dose escalation study is currently in preparation.

Summarizing, Kypho-IORT is technically feasible with an intra-operative risk profile comparable to sole kyphoplasty. We could not apply radiation in 10% of cases due to technical difficulties, which we have tried to decrease by further refining the equipment. However, as these patients can be treated by standard percutaneous radiation postoperatively, no negative effects for the patients occurred.

The theoretical benefits of faster pain relief, enhanced quality of life, and possible high-dose radiation with equal or better local disease control have not been proven so far in comparison with percutaneous radiation. Therefore further studies must show whether these aims can be achieved and if the clinical long-term results are satisfactory before final recommendations can be made. Despite the missing essential outcome data needed for final evaluation, the results of this feasibility study, as well as the theoretical advantages permit, in our opinion, further evaluation of the technique.

References

- 1.Aaron AD. The management of cancer metastatic to bone. JAMA. 1994;272:1206–1209. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520150074040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong DA, Fornasier VL, MacNab I. Spinal metastases: the obvious, the occult, and the impostors. Spine. 1990;15:1–4. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199001000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black P. Spinal metastasis: current status and recommended guidelines for management. Neurosurgery. 1979;5:726–746. doi: 10.1227/00006123-197912000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilbert RW, Kim JH, Posner JB. Epidural spinal cord compression from metastatic tumor: diagnosis and treatment. Ann Neurol. 1978;31:40–51. doi: 10.1002/ana.410030107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young RF, Post EM, King GA. Treatment of spinal epidural metastases Randomized prospective comparison of laminectomy and radiotherapy. J Neurosurg. 1980;53:741–748. doi: 10.3171/jns.1980.53.6.0741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF, Payne R, Saris S, Kryscio RJ, Moihuddin M, Young B. Direct decompressive surgical resection in the treatment of spinal cord compression caused by metastatic cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366:643–648. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66954-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witham TF, Khavkin YA, Gallia GL, Wolinksy JP, Gokaslan ZL. Surgery insight: current management of epidural spinal cord compression from metastatic spine disease. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2006;2:87–94. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang JS, Lee SH. Efficiacy of percutanoeus vertebroplasty combined with radiotherapy in osteolytic metastatic spinal tumors. J Neurosurgery Spine. 2005;2:243–248. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.3.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalbayrak S, Önen MR, Yilmaz M, Naderi S. Clinical and radiographic results of balloon kyphoplasty for treatment of vertebral body metastases and multiple myelomas. J Clin Neurosci. 2010;17:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fourney DR, Schomer DF, Nader R, Chlan Fourney J, Suki D, Ahrar K, Rhines LD, Gokaslan ZL. Percutaneous vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty for painful vertebral body fractures in cancer patients. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:21–30. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.1.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pflugmacher R, Beth P, Schroeder RJ, Schaser KD, Melcher I. Balloon kyphoplasty for the treatment of pathological fractures in the thoracic and lumbar spine caused by metastasis: one-year follow-up. Acta Radiol. 2007;48:89–95. doi: 10.1080/02841850601026427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendel E, Bourekas E, Gerszten P, Golan JD. Percutanoeus techniques in the treatment of spine tumors. What are the diagnostic and therapeutic indications and oucomes? Spine. 2009;34:S93–100. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b77895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moulding HD, Elder JB, Lis E, Lovelock DM, Zhang Z, Yamada Y, Bilsky MH. Local disease control after decompressive surgery and adjuvant high-dose single-fraction radiosurgery for spine metastases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13:87–93. doi: 10.3171/2010.3.SPINE09639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerszten PC, Burton SA, Ozhasoglu C, Welch WC. Radiosurgery for spinal metastases: clinical experience in 500 cases from a single institution. Spine. 2007;32:193–199. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000251863.76595.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Degen JW, Gagnon GJ, Voyadzis JM, McRae DA, Lunsden M, Dieterich S, Molzahn I, Henderson FC. CyberKnife stereotactic radiosurgical treatment of spinal tumors for pain control and quality of life. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:540–549. doi: 10.3171/spi.2005.2.5.0540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamada Y, Bilsky MH, Lovelock DM, Venkatraman ES, Toner S, Johnson J, Zatchky J, Zelefsky MJ, Fuks Z. High-dose, single-fraction image -guided intensity-modulated radiotherapy for metastatic spinal lesions. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:484–490. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim B, Soisson ET, Duma C, Chen P, Hafer R, Cox C, Cubellis J, Minion A, Plunkett M, Mackintosh R. Image-guided helical tomotherapy for treatment of spine tumors. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008;110:357–362. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2007.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerszten PC, Mendel E, Yamada Y. Radiotherapy and radiosurgery for metastatic spine disease. What are the options, indications, and outcomes? Spine. 2009;34:S78–92. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b8b6f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rose PS, Laufer I, Boland PJ, Hanover A, Bilsky MH, Yamada J, Lis E. Risk fracture after single fraction image-guided intensity-modulated radiation therapy to spinal metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5075–5079. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider F, Greineck F, Clausen S, Mai S, Obertacke U, Reis T, Wenz F (2010) Development of a novel method for intraoperative radiotherapy during kyphoplasty for spinal metastases (Kypho-IORT). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 81(4):1114–1119 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Wu JS, Wong R, Johnston M, Bezjak A, Whelan T, Group CCOPGISC Meta-analysis of dose-fractionation radiotherapy for the palliation of painful bone metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55:594–605. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)04147-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berenson J, Pflugmacher R, Jarzem P, Zonder J, Schechtman K, Tillman JB, Bastian L, Ashraf T, Vrionis F. Balloon kyphoplasty versus non-surgical management for treatment of painful vertebral body compression fractures in patients with cancer: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:225–235. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang SC, Chen WJ, Yu SW, Tu YK, Kao YH, Chung KC. Revision strategies for complications and failure of vertebroplasties. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:982–988. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0680-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]