Abstract

Objectives

To study the associations of pre-stroke cognitive performance with mortality after first-ever stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA).

Design

A prospective cohort study.

Setting and participants

In participants having first-ever stroke or TIA during up to 14 years of post-test follow-up (n=155), we investigated the associations of pre-stroke variables and cognitive test results with post-stroke survival. The study is based on those participants of the Uppsala Longitudinal Study of Adult Men who performed cognitive function tests at approximately age 70 (n=919).

Primary outcome measures

Mortality after first-ever stroke or TIA related to pre-stroke executive performance.

Results

Eighty-four (54%) of the first-ever stroke/TIA patients died under a median follow-up of 2.5 years after the event. In Cox proportional hazard analyses adjusting for age, education, social group and traditional stroke risk factors, poor performance in Trail Making Test (TMT)-A was related to mortality (HR 1.88 per SD, 95% CI 1.31 to 2.71, p=0.001). The risk of mortality was approximately threefold higher in the highest tertile compared with the lowest tertile (HR TMT-A= 2.90 per SD, 95% CI 1.24 to 6.77, p=0.014). A similar pattern was seen for TMT-B, but Mini-Mental State Examination results were not related to risk of post-stroke mortality.

Conclusion

Executive performance measured by TMT-A and -B before stroke was independently associated with long-term risk of mortality, after first-ever stroke or TIA in a population-based study of older men.

Article summary

Article focus

Risk factors for mortality after stroke with focus on pre-stroke cognitive tests.

Key messages

Executive performance pre-stroke measured with Trail Making Test (TMT)-A and -B strongly predicts mortality after stroke. Cognitive testing with Mini-Mental State Examination was not related to risk of post-stroke mortality.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Strength is that the study is based on a large representative community-based sample with long follow-up without any loss, and with vast information on traditional risk factors. Limitation is that the participants only are Caucasian men.

Introduction

In recent years, stroke seems to have become a less severe disease.1 Several authors have studied prognostic factors for mortality and dependency after stroke in attempts to identify and intervene with risk factors determining the stroke outcome. Well-defined prediction models of outcome could also have important implications in clinical practice in guiding the management and improving information to patients and relatives. It is well established that high age and severe impairment predict a poor outcome after a stroke. Other known prognostic factors for 30-day survival include cardiac failure, level of consciousness and grade of impairment.2 Appelros et al performed one of the few population-based studies on this matter, and their study also took into account pre-stroke conditions. In their cohort in Örebro, Sweden (n=377) followed up for 1 year post-stroke, heart disease and dementia were found to have predictive power for mortality and morbidity.3 4 Pre-stroke risk factors for stroke severity need to be studied in greater detail and with longer follow-up.

In earlier studies of the cohort participating in the Uppsala Longitudinal Study of Adult Men (ULSAM), we observed that besides traditional stroke risk factors, performance in the cognitive test Trail Making Test (TMT)-B at age 70 carried important information as a predictor of later incidence of stroke, especially brain infarction (BI).5 A poor result in the latter test is believed to represent subclinical cognitive deficits due to silent cerebrovascular disease.6 In the present study, we addressed the question whether cognitive function measured with TMT-A and -B and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in the pre-stroke setting were associated with risk of mortality after first-ever stroke. These questions were investigated in an extensively characterised community-based sample of 70-year-old men followed for up to 14 years through registry data from the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare and discharge records.

Methods

Study sample

The study was based on the ULSAM cohort (http://www.pubcare.uu.se/ULSAM) participating in a health investigation focusing on identification of metabolic risk factors for cardiovascular disease, to which all 50-year-old men living in Uppsala, Sweden, in 1970–1974 were invited. The ULSAM originally comprised 2322 participants (82% of the invited). A re-investigation was performed around 20 years later between 1991 and 1995. Of the 1681 participants available who were invited to that investigation, 1221 (73%) attended. Seventy-eight participants were excluded because of a history of stroke/transient ischaemic attack (TIA) before the investigation and eight because of misdiagnosis in the registry, rendering 1135 men eligible. In subsequent tests of cognitive function performed in 1993–1996, 930 of the eligible participants took part. After additional exclusion of 11 participants who had had a stroke/TIA between the baseline examination and the cognitive testing, 919 were available for the present study. All medical records from the hospitalisation of those suffering a first-ever stroke/TIA were reviewed by one physician (BW).

In the whole ULSAM cohort based on the investigation at age 50 (n=2322), 232 men had experienced a first stroke and 586 had died, before the planned date of cognitive function tests.

Clinical examinations

The ULSAM examinations have previously been described in detail.7 8 The baseline investigation for the present study was performed when the participants were 69–75 years old and included a medical questionnaire concerning previous diseases, alcohol habits and medical treatment. The participants were physically examined, including anthropometric measurements. Supine blood pressure was measured under standardised conditions. Hypertension was defined as a supine blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg or higher and/or treatment with antihypertensive drugs. Blood samples were drawn in the morning after an overnight fast. Cholesterol concentrations were measured in serum by enzymatic techniques using IL test cholesterol Trinder's Method for use in a Monarch apparatus (Instrumentation Laboratories, Lexington, KT, USA). High-density lipoprotein particles were separated by precipitation with magnesium chloride/phosphotungstate. Diabetes was defined according to the 1997 criteria of American Diabetes Association.9 A standard 12-lead ECG was recorded. The revised Minnesota code was used for classification,10 11 and left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) was defined as high-amplitude R-waves together with a left ventricular strain pattern. The coding of education was as follows: (1) elementary school only (6–8 years), (2) secondary school (12 years) and (3) 3 or more years of college or graduate examination. The coding of smoking and social group classification was based on interview reports. The three conventional social classes were used and classified in accordance with the Central Bureau of Statistics.12

Cognitive function tests

In TMT-A, the participant is asked to draw lines with a pencil between numbers in ascending order, as fast as possible.13 In TMT-B, letters are also added, and the task is to alternate between letters and numbers in ascending order. The score is equal to the time taken to complete the test, in seconds. The standard TMT-A consists of digits 1–25 and TMT-B consists of digits and letters (1-A-2-B- … -K-12-L-13). The maximum time set for TMT-B was 240 s, and 41 participants reached that level. A long completion time reflects impaired psychomotor speed.

The MMSE14 is a screening test for dementia and cognitive decline and is widely used both in clinical practice and in research. It has the advantage of being easy to administer and has a high replicability, but from clinical practice, it is known to only give a limited information of cognitive performance in the patients with stroke. The scores range from 0 (worst) to 30 (best). MMSE was added to the test battery after the start, and thus, the number of participants is slightly smaller than in the other cognitive tests. The cognitive examinations have been described earlier in detail.5

Follow-up

The sample was followed up from the first investigation at age 70, that is, from August 1991–May 1995 to 31 December 2006. None of the subjects was lost to follow-up.

End point

Stroke/TIA and survival were recorded on the bases of the Swedish Hospital Discharge Record and Cause of Death Registries and validated by examination of all the medical records by one physician (BW). The stroke cases investigated in the present study were as follows:

Fatal or non-fatal stroke or TIA (ICD-9 codes 430–31 and 434–436, ICD-10 codes I60–61, I63.0–I63.5, I63.8–9, I64 and G45).

Fatal or non-fatal BI (ICD-9 code 434; ICD-10 codes I63.0–I63.5 and I63.8–9). The end points were mortality after a first-ever stroke/TIA-event.

Statistical methods

Distributions were tested for normality by the Shapiro–Wilk W test, and logarithmic transformation was performed when necessary to obtain normality (TMT-A and -B). The prognostic value of a 1SD increase in the continuous variables or transfer from one level to another of the dichotomous variables was investigated with Cox proportional HRs. Four MMSE groups as equal in size as possible were considered (≤27, 28, 29 and 30 points). Interaction terms between all baseline covariates were examined, and no evidence of effect modification was found. We examined three sets of models in a hierarchical fashion:

Models A adjusting for age at baseline.

Models B adjusting for age, education and social group at baseline.

Models C adjusting for the following baseline covariates: age, education, social group, systolic blood pressure, hypertension treatment, serum cholesterol, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, ECG-LVH and current smoking.

Proportional hazards assumptions were confirmed graphically and by Schoenfeld's test. Two-tailed 95% CIs and p values were given, with p<0.05 regarded as significant.

Kaplan–Meier curves for TMT-A and -B in tertiles were used for survival estimates. Authors BW and LB performed all statistical analyses, using Stata V.10.1 (Stata Corporation).

Results

Characteristics from the examination at age 70 years are presented in table 1. The mortality incidence rate among the 155 subjects with stroke/TIA was 148/1000 person-years at risk (PYAR) (84 deaths during 566 PYAR). The median follow-up to the first stroke/TIA event was 11.2 years (maximum 13.6 years), and the median follow-up after first-ever stroke/TIA was 2.5 years (maximum 12.2 years), contributing to 566 PYAR. A total of 84 men died during the time of follow-up (54%), of which 22 died within 1 month (14%) and 42 within 1 year (27%). The diagnoses were BI in 97 cases, intracerebral haemorrhage in 24 cases and the rest being TIA, unspecified stroke or subarachnoid haemorrhage. Of those suffering a BI, 53 died during follow-up.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics at age 70

| All participants (n=919) | Participants with stroke/TIA (n=155) | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 146 (18) | 151 (19) |

| S-total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 5.8 (1.0) | 5.9 (1.1) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 36 (4%) | 9 (10%) |

| ECG-LVH | 65 (7%) | 14 (16%) |

| Hypertension prevalence | 676 (74%) | 82 (84%) |

| Diabetes prevalence | 159 (17%) | 21 (22%) |

| Treatment with hypertension medicine | 306 (33%) | 44 (45%) |

| Treatment with diabetes medicine | 48 (5%) | 7 (7%) |

| Treatment with lipid-lowering medicine | 80 (9%) | 14 (16%) |

| Current cigarette smoking | 174 (19%) | 23 (24%) |

| Education | ||

| Elementary school only (7 or 8 years) | 571 (81%) | 53 (74%) |

| Secondary school (12 years) | 51 (7%) | 8 (11%) |

| Three or more years of college or graduate examination | 107 (15%) | 11 (15%) |

| Social group | ||

| Low | 388 (42%) | 39 (40%) |

| Middle | 361 (39%) | 36 (37%) |

| High | 169 (18%) | 22 (23%) |

| Mini-Mental State Examination | ||

| Group ≤27 points | 182 (22%) | 21 (24%) |

| Group 28 points | 181 (22%) | 20 (23%) |

| Group 29 points | 264 (32%) | 27 (31%) |

| Group 30 points | 192 (23%) | 18 (21%) |

| Trail Making Test-A (seconds) | 47 (20) | 48 (20) |

| Trail Making Test-B (seconds) | 119 (48) | 127 (46) |

Data are presented as means (SDs) or numbers of individuals (%).

Diabetes is defined according to the 1997 American Diabetes Association criteria.

LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; S, serum; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Relations of baseline variables at age 70 to the first-ever stroke mortality up to the end of follow-up are presented in table 2. In Cox proportional hazard models adjusting for age at baseline, the prevalence of ECG-LVH, diabetes and treatment with antihypertensives at baseline were strongly related to death after first-ever stroke. This was also true when the subgroup of BIs was analysed in all models (eg, HR 2.40, 95% CI 1.24 to 4.66 for ECG-LVH prevalence and HR 2.01, 95% CI 1.06 to 3.80 for diabetes prevalence in models C). No other investigated variable showed any significant relation to mortality in the total stroke sample or in the subgroup of BIs in these analyses except for treatment with lipid lowering in the subgroup of BIs.

Table 2.

Relations of baseline clinical variables to mortality after first-ever stroke

| All stroke/TIA (n=155), 84 died during follow-up | Brain infarction (n=97), 53 died during follow-up | |

| Adjusted for age at baseline models A | Adjusted for age at baseline models A | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.02) | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.01) |

| p=0.418 | p=0.730 | |

| S-total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 0.85 (0.69 to 1.04) | 0.88 (0.66 to 1.17) |

| p=0.122 | p=0.384 | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.14 (0.56 to 2.29) | 0.54 (0.20 to 1.43) |

| p=0.722 | p=0.216 | |

| ECG-LVH | 1.88 (1.04 to 3.39) | 2.54 (1.25 to 5.15) |

| p=0.035 | p=0.010 | |

| Hypertension prevalence | 1.19 (0.64 to 2.20) | 1.66 (0.74 to 3.71) |

| p=0.576 | p=0.217 | |

| Diabetes prevalence | 1.67 (1.04 to 2.69) | 1.85 (1.00 to 3.41) |

| p=0.035 | p=0.050 | |

| Treatment with antihypertensives | 1.56 (1.02 to 2.40) | 2.60 (1.50 to 4.50) |

| p=0.042 | p=0.001 | |

| Treatment with antidiabetics | 1.28 (0.71 to 2.39) | 1.48 (0.58 to 3.77) |

| p=0.514 | p=0.410 | |

| Treatment with lipid-lowering medicine | 1.53 (0.83 to 2.84) | 2.17 (1.01 to 4.65) |

| p=0.173 | p=0.046 | |

| Current cigarette smoking | 0.97 (0.56 to 1.69) | 1.05 (0.54 to 2.04) |

| p=0.921 | p=0.885 |

Data are presented as Cox proportional HRs (95% CI) for a 1SD increase in the continuous variables or transfer from one level to another of the dichotomous variables.

LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; S, serum; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Both TMT-A and -B strongly predicted survival in Cox proportional hazard analyses, but no significant relation between MMSE scores and future mortality was seen (table 3).

Table 3.

Relations of baseline cognitive function variables to mortality after first-ever stroke/TIA

| All stroke/TIA (n=155), 84 died during follow-up |

Brain infarction (n=97), 53 died during follow-up |

|||||

| Adjusted for age at baseline | Adjusted for age at baseline, education and social group | Multivariable adjusted models | Adjusted for age at baseline | Adjusted for age at baseline, education and social group | Multivariable adjusted models | |

| Models A | Models B | Models C | Models A | Models B | Models C | |

| Trail Making Test-A | ||||||

| As continuous variable | 1.45 (1.15 to 1.82) | 1.67 (1.24 to 2.23) | 1.88 (1.31 to 2.71) | 1.27 (0.92 to 1.76) | 1.47 (0.96 to 2.25) | 1.45 (0.97 to 2.17) |

| p=0.002 | p=0.001 | p=0.001 | p=0.137 | p=0.075 | p=0.068 | |

| Tertile 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tertile 2 | 1.47 (0.84 to 2.56) | 1.54 (0.73 to 3.27) | 2.09 (0.85 to 5.11) | 1.54 (0.76 to 3.09) | 1.41 (0.51 to 3.86) | 1.91 (0.82 to 4.47) |

| p=0.173 | p=0.258 | p=0.107 | p=0.226 | p=0.505 | p=0.133 | |

| Tertile 3 | 1.84 (1.07 to 3.17) | 2.26 (1.13 to 4.53) | 2.90 (1.24 to 6.77) | 1.33 (0.65 to 2.73) | 1.43 (0.54 to 3.75) | 1.59 (0.64 to 3.92) |

| p=0.027 | p=0.021 | p=0.014 | p=0.442 | p=0.468 | p=0.315 | |

| Trail Making Test-B | ||||||

| As continuous variable | 1.20 (0.96 to 1.51) | 1.79 (1.21 to 2.66) | 2.01 (1.28 to 3.15) | 1.00 (0.74 to 1.35) | 1.63 (0.90 to 2.95) | 1.15 (0.77 to 1.72) |

| p=0.115 | p=0.004 | p=0.002 | p=0.985 | p=0.108 | p=0.488 | |

| Tertile 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tertile 2 | 1.55 (0.86 to 2.81) | 1.57 (0.70 to 3.53) | 2.11 (0.82 to 5.46) | 0.83 (0.39 to 1.76) | 0.72 (0.21 to 2.43) | 0.74 (0.30 to 1.85) |

| p=0.149 | p=0.275 | p=0.124 | p=0.632 | p=0.597 | p=0.521 | |

| Tertile 3 | 1.63 (0.91 to 2.92) | 3.07 (1.22 to 7.73) | 3.53 (1.21 to 10.34) | 0.96 (0.47 to 1.96) | 1.53 (0.42 to 5.49) | 1.40 (0.58 to 3.35) |

| p=0.103 | p=0.017 | p=0.021 | p=0.915 | p=0.516 | p=0.452 | |

| MMSE | ||||||

| Group 30 points | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Group ≤27 points | 1.22 (0.63 to 2.34) | 1.35 (0.55 to 3.31) | 0.81 (0.23 to 2.86) | 0.52 (0.22 to 1.22) | 0.71 (0.21 to 2.39) | 0.54 (0.17 to 1.71) |

| p=0.558 | p=0.518 | p=0.746 | p=0.132 | p=0.584 | p=0.293 | |

| Group 28 points | 1.56 (0.80 to 3.04) | 1.92 (0.84 to 4.43) | 1.80 (0.65 to 4.97) | 1.17 (0.51 to 2.67) | 2.08 (0.67 to 6.45) | 1.09 (0.36 to 3.32) |

| p=0.197 | p=0.123 | p=0.259 | p=0.715 | p=0.205 | p=0.874 | |

| Group 29 points | 1.03 (0.55 to 1.91) | 1.35 (0.61 to 2.98) | 1.27 (0.53 to 3.04) | 0.63 (0.26 to 1.49) | 0.85 (0.24 to 2.94) | 0.42 (0.14 to 1.26) |

| p=0.928 | p=0.456 | p=0.596 | p=0.294 | p=0.795 | p=0.122 | |

Data are presented as Cox proportional HRs (95% CIs) for a 1SD increase in the continuous variables or transfer from one level to another of the dichotomous variables.

MMSE 30 points and TMT-A and -B tertile 1 were used as references.

MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

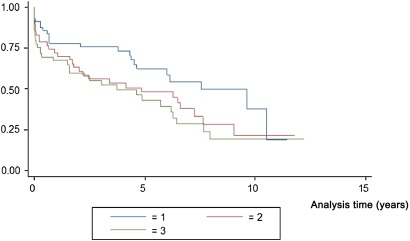

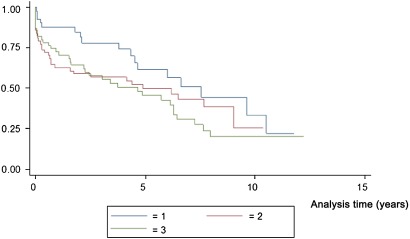

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates for TMT-A by tertiles are displayed in figure 1 and for TMT-B by tertiles in figure 2. The survival decreased gradually with higher tertiles.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates for Trail Making Test A in tertiles.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates for Trail Making Test B in tertiles.

Incidence rates were similar in stratified analyses by tertiles of the independent variables, suggesting no major deviation from linearity (data not shown).

Discussion

In this community-based sample of elderly men, free from stroke/TIA at baseline, pre-stroke executive function, as measured by TMT-A and -B, predicted survival independent of education, social group and traditional stroke risk factors, as described in previous studies,15–18 whereas MMSE had no predictive power in this respect. Failure in our study to detect association to MMSE could be explained by a good general cognitive performance. As no one in the sample had a MMSE score <21 points and the median score was 29 points, our sample represents a non-demented population.

In a systematic review article validating prognostic models by Counsell et al, cardiac failure, level of consciousness and grade of impairment were the predictors of survival after 30 days in patients with stroke. Pre-stroke overt dementia has previously been observed to be a predictor for initial stroke severity and 28-day and 1-year case death.3 4 19 Patients with small-vessel disease have an augmented risk of death after a stroke event.20As poor performance in TMT-A and -B in a non-demented population may be interpreted as impaired subcortical function, our findings regarding survival point in the same direction. The present study is unique in its kind since the cognitive function evaluation was performed up to 12 years before the stroke event.

Executive dysfunction in an elderly population may be a manifestation of clinically unrealised cerebrovascular disease21 and seems to be an objective in small vessel disease.22 Lines of research suggest associations between vascular risk factors, such as age, hypertension, smoking and glucometabolic disturbances,23–26 and brain atrophy, white matter abnormalities and silent cerebral infarctions.6 27–29 These vascular risk factors could be the cause of brain lesions, not yet recognised clinically, and earlier studies have shown associations between cerebrovascular risk factor burden and a broad range of cognitive abilities.30 31 Ischaemic small vessel disease is recently underlined as a potentially severe condition prodrome of subcortical vascular dementia.20

Biological ageing of the brain is partly attributable to ageing of the cerebrovascular circulation and effects of these vascular changes on the brain.32 33Mid-life stroke risk factors have been related to late-life cognitive impairment. The importance of managing stroke risk factors is further reinforced by the inverse association between global atrophy measured with MRI and results from cognitive testing.31

Earlier cross-sectional studies on the ULSAM cohort have also demonstrated that high 24-h BP, non-dipping, insulin resistance and diabetes were all related to low cognitive function.33 Our own earlier studies on this cohort indicated that the risk of BI was increased in men with poor TMT-B test results.5

Remarkable in this study, as the risk of stroke/TIA related to TMT-A and -B scores increase when adjusting for education and social factors (models B) and further in the multivariable-adjusted model (models C), is that the risk related to the tests seem to exist separately, beside the track of traditional stroke risk factors.

Our study has strengths. It is based on a large community-based sample, and it has a long follow-up with a large number of persons with incident stroke, non-existent loss to follow-up and extensive information on traditional risk factors, reducing the risk of confounding. All stroke and TIA cases have been examined in detail through medical records. The sample is also representative of the general population in Sweden regarding stroke incidence, according to data published by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare (http://www.sos.se/sosmeny.htm). The accuracy of the Swedish Hospital Discharge Record and the Cause of Death Registries has been shown to be high regarding stroke diagnosis.34 Limitations include an unknown generalisability to women and to other age and ethnic groups, as only men of similar age and ethnic background were examined. The present cohort has been re-examined a few times since baseline and risk factors have been treated and the men of the cohort may therefore have been healthier during follow-up than the average man of the same age. It is unlikely, however, that this would have influenced the associations we have demonstrated in our study.

Regarding TMT-A and -B, it has been suggested that the difference between the two tests might be a more pure measure of executive function independent from individual differences in psychomotor speed.35 However, creating a difference or a ratio may also introduce bias in the estimate and increases the measurement error why we chose not to.

Pre-stroke cognitive performance measured with TMT-A and -B in a population-based study strongly predicted post-stroke mortality independent of education, socioeconomic status or traditional risk factors. Thus, TMT-A and -B, easily accessible cognitive tests for clinical use, may not only be used as tools for identifying risk of stroke but may also be considered important predictors of post-stroke mortality.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Wiberg B, Kilander L, Sundström J, et al. The relationship between executive dysfunction and post-stroke mortality: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000458. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000458

Contributors: BW gave substantial contributions to conception and design, was responsible for the statistical analyses, the interpretation of data and the writing of the manuscript. LK was deeply involved in acquisition of data, especially the cognitive testing and has given important comments to the manuscript. JS has given important support concerning the statistical analyses and revising of the article critically for important intellectual content. LB has been deeply involved in the statistical analyses and given important comments to the article. LL has given structure to the work in general and in choosing statistical analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was kindly supported by grants from the Medical Faculty at Uppsala University and STROKE-Riksförbundet.

Competing interests: BW, LK and LB report no disclosures. JS serves on a scientific advisory board for Itrim. LL receives research support from AstraZeneca.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was provided by the ethics committee of Uppsala University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional unpublished data.

References

- 1.Stegmayr B, Asplund K. Exploring the declining case fatality in acute stroke. Population-based observations in the northern Sweden MONICA Project. J Intern Med 1996;240:143–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Counsell C, Dennis M. Systematic review of prognostic models in patients with acute stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 2001;12:159–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appelros P, Nydevik I, Seiger A, et al. Predictors of severe stroke: influence of preexisting dementia and cardiac disorders. Stroke 2002;33:2357–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appelros P, Nydevik I, Viitanen M. Poor outcome after first-ever stroke: predictors for death, dependency, and recurrent stroke within the first year. Stroke 2003;34:122–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiberg B, Lind L, Kilander L, et al. Cognitive function and risk of stroke in elderly men. Neurology 2010;74:379–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desmond DW. Cognition and white matter lesions. Cerebrovasc Dis 2002;13(Suppl 2):53–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hedstrand H, Boberg J. Statistical analysis of the reproducibility of the intravenous glucose tolerance test and the serum insulin response to this test in the middle-aged men. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1975;35:331–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiberg B, Sundstrom J, Zethelius B, et al. Insulin sensitivity measured by the euglycaemic insulin clamp and proinsulin levels as predictors of stroke in elderly men. Diabetologia 2009;52:90–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anonymous. American Diabetes Association: clinical practice recommendations 1997. Diabetes Care 1997;20(Suppl 1):S1–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prineas R, Crow R, Blackburn H. The Minnesota Code Manual of Electrocardiographic Findings Standards and Procedures for Measurement and Classification. Boston, MA: J Wright, 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blackburn H, Keys A, Simonson E, et al. The electrocardiogram in population studies. A classification system. Circulation 1960;21:1160–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersen R, Smedby B, Anderson DW. Medical Care Use in Sweden and the United States. A Comparative Analysis of Systems and Behaviour. Chicago: University of Chicago, Center for health Administration studies, 1970 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lezak M. Neuropsychological Assessement. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kannel WB, Wolf PA, Verter J, et al. Epidemiologic assessment of the role of blood pressure in stroke. The Framingham study. JAMA 1970;214:301–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, et al. Probability of stroke: a risk profile from the Framingham Study. Stroke 1991;22:312–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez BL, D'Agostino R, Abbott RD, et al. Risk of hospitalized stroke in men enrolled in the Honolulu Heart Program and the Framingham Study: a comparison of incidence and risk factor effects. Stroke 2002;33:230–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rautio A, Eliasson M, Stegmayr B. Favorable trends in the incidence and outcome in stroke in nondiabetic and diabetic subjects: findings from the Northern Sweden MONICA Stroke Registry in 1985 to 2003. Stroke 2008;39:3137–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oksala NK, Jokinen H, Melkas S, et al. Cognitive impairment predicts poststroke death in long-term follow-up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009;80:1230–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grau-Olivares M, Arboix A. Mild cognitive impairment in stroke patients with ischemic cerebral small-vessel disease: a forerunner of vascular dementia? Expert Rev Neurother 2009;9:1201–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vermeer SE, Prins ND, den Heijer T, et al. Silent brain infarcts and the risk of dementia and cognitive decline. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1215–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown RD, Whisnant JP, Sicks JD, et al. Stroke incidence, prevalence, and survival: secular trends in Rochester, Minnesota, through 1989. Stroke 1996;27:373–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The Framingham study. JAMA 1979;241:2035–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacMahon S, Peto R, Cutler J, et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1, Prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet 1990;335:765–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shinton R, Beevers G. Meta-analysis of relation between cigarette smoking and stroke. BMJ 1989;298:789–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeCarli C, Miller BL, Swan GE, et al. Predictors of brain morphology for the men of the NHLBI twin study. Stroke 1999;30:529–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vermeer SE, Hollander M, van Dijk EJ, et al. Silent brain infarcts and white matter lesions increase stroke risk in the general population: the Rotterdam Scan Study. Stroke 2003;34:1126–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seshadri S, Wolf PA, Beiser A, et al. Stroke risk profile, brain volume, and cognitive function: the Framingham Offspring Study. Neurology 2004;63:1591–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elias MF, Sullivan LM, D'Agostino RB, et al. Framingham stroke risk profile and lowered cognitive performance. Stroke 2004;35:404–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Llewellyn DJ, Lang IA, Xie J, et al. Framingham Stroke Risk Profile and poor cognitive function: a population-based study. BMC Neurol 2008;8:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seshadri S. Methodology for measuring cerebrovascular disease burden. Int Rev Psychiatry 2006;18:409–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brady CB, Spiro A, 3rd, McGlinchey-Berroth R, et al. Stroke risk predicts verbal fluency decline in healthy older men: evidence from the normative aging study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2001;56:P340–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kilander L, Nyman H, Boberg M, et al. Hypertension is related to cognitive impairment: a 20-year follow-up of 999 men. Hypertension 1998;31:780–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merlo J, Lindblad U, Pessah-Rasmussen H, et al. Comparison of different procedures to identify probable cases of myocardial infarction and stroke in two Swedish prospective cohort studies using local and national routine registers. Eur J Epidemiol 2000;16:235–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arbuthnott K, Frank J. Trail making test, part B as a measure of executive control: validation using a set-switching paradigm. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2000;22:518–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.