Abstract

Background

Clinicians and researchers working with dementia caregivers typically assess caregiver stress in a clinic or research center, but caregivers’ stress is rooted at home where they provide care. The study aimed to compare ratings of stress-related measures obtained in research setting and home using ecological momentary assessment (EMA).

Methods

EMA of 18 caregivers (mean age 66.4±7.8, 89% females) and 23 non-caregivers (mean age 66.4±7.9, 87% females) was implemented using a personal digital assistant. Subjects rated their perceived stress, fatigue, coping with current situation, mindfulness, and situational demand once in the research center and again at 3–4 semi-random points during a day at home. The data from several assessments conducted at home were averaged for statistical analyses and compared to the data collected in the research center.

Results

Testing environment had a differential effect on caregivers and non-caregivers for the ratings of perceived stress (p < 0.01) and situational demand (p = 0.01). When tested in research center, ratings for all measures were similar between groups, but when tested at home, caregivers rated their perceived stress higher than non-caregivers (p = 0.02). Overall, caregivers reported higher perceived stress at home than in the research center (p = 0.02), and non-caregivers reported greater situational demand in the research center than at home (p < 0.01).

Conclusions

The assessment method and environment affect stress-related outcomes. Evaluating participants in their natural environment provides a more sensitive measure of stress-related outcomes. EMA provides a convenient way to gather data when evaluating dementia caregivers.

Keywords: caregivers, ecological momentary assessment, EMA, older adults, perceived stress

INTRODUCTION

Caregivers of relatives with dementia represent over 10 million people in the US alone, and this population is growing due to an increased survival to older age (Schulz and Martire, 2004). Dementia caregivers experience chronic stress associated with serious health-related problems in this population (Mills et al., 2009, von Kanel et al., 2010, Fonareva et al., 2011, Schulz and Sherwood, 2008) impacting quality of care they provide. Every caregiver is an asset for the family and society, and ensuring their well-being is an important goal for caregivers’ primary care providers as well as researchers evaluating interventions for combating effects of caregiving stress and improving coping with the caregiving burden (Schulz and Martire, 2004).

Accurate assessment of physical and psychological symptoms of dementia caregivers is critical for both primary care providers and investigators involved in caregiver research. Some of the most important aspects of function affecting caregivers’ health that are also critical to assess in interventional studies include perceived stress and stress-related measures such as fatigue, attitudes to caregiving, and coping with the caregiving burden. These measures are usually assessed either in a clinic or research center by self-reports that summarize symptoms over a certain period of time retrospectively, e.g., how much people felt “stressed” in the previous week. This type of retrospective recall is affected by biases such as state (e.g. current mood state) or recall biases (e.g. recent events more easily recalled) (Yoshiuchi et al., 2008). Furthermore, the source of caregiver stress originates at home, and asking caregivers how stressed they feel in a clinic or research center might not be optimal when evaluating perceived stress due to caregiving. When using typical assessment methods outside the home, clinicians might underestimate the severity of the caregiver’s home situation. In fact, reviews of several studies testing dementia caregivers interventions indicated modest effect sizes on stress-related outcomes and also suggested there might be a room for improvement in quality of interventions as well as in quality of evaluations (Acton and Kang, 2001, Brodaty et al., 2003, Pinquart and Sorensen, 2006, Thompson et al., 2007, Smits et al., 2007). Some of these results might be due to sub-optimal evaluation methodology including using retrospective recall measures in artificial environments when assessing main outcomes. Exploring alternative assessment methods that avoid recall biases and permit testing in natural environments is an important step in furthering research in caregiver population interventions.

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is a method evaluating “phenomena at the moment they occur in natural settings, thus maximizing ecological validity while avoiding retrospective recall” (Yoshiuchi et al., 2008). Crucial EMA features include collecting data in subjects’ natural environments, assessing current feelings or states rather than recall of past experiences, and performing multiple evaluations (Shiffman et al., 2008). EMA can be implemented as questionnaires accessible via palm-size computers or touch-phones that can be programmed to alert people during the day to complete brief assessments of their current situation (Shiffman et al., 2008). Numerous studies have successfully used EMA for assessment of various psychosocial and physiological outcomes ranging from engagement in physical activity to craving abused drugs (Shiffman et al., 2008). Our first aim was to evaluate feasibility and utility of EMA for evaluating stress-related outcomes in a sample of elderly dementia caregivers and non-caregivers. Our second aim was to compare results of stress-related assessments conducted in the research center and in home environment between dementia caregivers and non-caregivers using EMA. We hypothesized that ratings of stress-related measures are differentially affected by assessment environment in caregivers and non-caregivers, with caregivers reporting greater stress at home than in the research center. To the best of our knowledge this is the first study utilizing EMA for evaluating stress-related outcomes in caregivers and non-caregivers with results compared between research center and home environments.

METHODS

Participants

Participants included 41 adults (mean age, 66.4 years; 97.6 % white) from Portland, OR metro area. Consent and preliminary screening were completed prior to participating in study procedures. Study inclusion criteria were age between 50 and 85 and being in good physical and cognitive health. Exclusion criteria, evaluated by a self-report during a screening interview, included serious medical conditions (e.g. cancer), significant current mental health problems (e.g. untreated major depression), diagnosis of neurological or sleep disorders, use of medications affecting cognitive function, starting new medications less than 2 months ago, recent use of illicit drugs, and excessive alcohol consumption.

Participants for the caregiver group had to be primary caregivers for a family member with dementia. They had to be involved in the care of their relative with dementia at least 12 hours a week. Enrolled caregivers participated in a mind-body intervention study to reduce stress (Oken et al., 2010), but the assessments for the current study were completed at the baseline visit prior to randomization and any interventions. Caregivers were recruited by posting study flyers at the university neurology clinic and in the community, as well as by advertising in local caregiver support groups.

The participants for the non-caregiver group had to be free of any caregiving duties and of any major stress (e.g. recent death in the family) at the time of the study. Non-caregivers were recruited from the community by posting study flyers at adult community centers and other public locations. To control for seasonal effects subjects for both groups were recruited in several interleaved cohorts. The study protocol was approved by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Baseline self-report measures

Prior to completing EMAs all participants completed the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), a commonly used measure assessing perceptions of stress during the previous week (Cohen et al., 1983). The PSS was only used at baseline to evaluate group differences in perceived stress at intake. The caregivers also filled out the Revised Memory and Behavior Problem Checklist (RMBPC) that assesses behaviors of care recipients and caregivers’ reactions to the reported behaviors (Teri et al., 1992).

Ecological Momentary Assessment questions

EMA testing included five questions assessing several stress-related measures. Though some questions (e.g. current fatigue) were adapted from widely used instruments (Hoddes et al., 1973), these five questions do not comprise a validated instrument but rather were chosen based on our previous findings indicating aspects of functioning affected by caregiving and remediable by a stress-reducing intervention (Oken et al., 2010). Our goal was to have a brief assessment that takes under 5 minutes to complete to minimize the burden on our participants. The questions with the rating scales that were used for EMA assessment at home and in the research center are presented in Appendix 1.

Appendix 1.

Questions used for the research center assessment and at home EMA and comparisons

| Questions/ Answers | Construct |

|---|---|

1. How do you currently feel?

|

Current perceived stress |

2. How well are you coping with the current situation?

|

Coping with current situation |

3. Where is the main focus of your current thoughts?

|

Mindfulness |

4. What kind of situation are you currently in?

|

Current situational demand |

5. How sleepy are you right now?

|

Current fatigue |

Ecological Momentary Assessment implementation and protocol

EMA was implemented using a personal digital assistant (PDA), Dell® Axim x51v running Microsoft® Windows Mobile 6.1. The assessment included a brief questionnaire consisting of the 5 questions described in Appendix 1. Each question was displayed separately on the screen followed by the prompt asking participants to rate each of the measures (current perceived stress, ability to cope with the present situation, mindfulness, demand of the present situation, and fatigue).

Research center assessment

During the research center visit, participants received training on using the PDA and completed a single 5-minute assessment identical to the EMA presented in their home. At the end of the visit, a research assistant inquired about the participant’s bedtime and wake times and plans for the rest of the day. This information was used to program the PDA to initiate the assessments at 3–4 semi-random points during participants’ wakeful hours. Participants did not know the times or number of scheduled EMAs.

EMA in home environment

In the home environment an alarm signaled the beginning of semi-randomly scheduled assessments. If the alarm sounded at an inconvenient time participants could postpone the assessment for 10 minutes. If after postponing the EMA twice the participant was not able to complete it, that particular assessment was automatically abandoned. The software stored the data and information including time of all scheduled, incomplete, and completed assessments.

The following day a research assistant collected the PDA at the participant’s home and inquired about their experience including any problems associated with using the device.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 19 for Windows. Demographic data for the two groups were compared using t- or Chi-Square tests.

For each assessment measure, for each participant, we used a single score obtained during the research center visit for the research center assessments and an average score calculated from all the completed at-home assessments for at-home EMAs.

Preliminary data screening indicated that some of the discrete data for the stress-related outcome variables had skewed distributions that could not be normalized, thus not meeting the assumptions for the use of parametric statistical analyses. Therefore, non-parametric statistical analyses were utilized.

To evaluate our first hypothesis that stress-related measures are differentially affected by assessment environment in caregivers and non-caregivers we used Pearson Chi-Square tests to compare distributions of participants in caregiver and non-caregiver groups based on their ratings in different environments coded the following way: 1) participants with ratings higher at home vs. research center, 2) participants with ratings lower at home vs. research center, and 3) participants with the same ratings in both testing environments. The significance level for these series of analyses was adjusted to p ≤ 0.01 to account for 5 stress-related variables assessed.

We followed these analyses with Mann-Whitney U tests to determine whether any group differences in ratings of the stress-related measures with significant Chi-Square values exist in either research center or home environments. Secondary analyses using Mann-Whitney U tests to determine any group differences in ratings were also conducted for the rest of the stress-related measures used in the study. Due to a sample size in our study below 42, exact significance values are reported for all Mann-Whitney U tests.

To evaluate our second hypothesis that caregivers report greater stress at home than in the research center we used the sign test to evaluate within-subject differences between testing environments for ratings of stress-related measures that were differentially affected by testing environment as determined by Chi-Square analyses described above. We also conducted similar secondary analyses with non-caregivers. The significance level for these analyses was adjusted to p ≤ 0.025 to account for 2 stress-related variables that were significantly affected by testing environment.

RESULTS

Group characteristics

Caregiver and non-caregiver groups were similar in age, education, and gender distribution (all p’s > 0.05). As expected, compared to non-caregivers, caregivers reported significantly greater perceived stress in the previous week on PSS at baseline, t (39) = 3.20, p = 0.001. The participants in both groups were similar on their health status. The most common health problem reported by participants in both groups was hypertension controlled with medication. Other conditions reported by participants included noninsulin dependent diabetes, mild asthma, thyroid deficiency, and acid reflux--- all of the above controlled with medication. Groups also had a similar frequency of history of depression controlled by medication. All p’s for health-related measures were non-significant, p > 0.05. Table 1 presents group demographics and baseline characteristics.

Table 1. Group baseline characteristics.

Study groups were similar on age, gender, and education, but caregivers reported greater baseline levels of stress.

| Characteristic | Caregivers (n = 18) | Non-caregivers (n = 23) | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | (p) | |

| Age (years) | 66.4 ± 7.8 | 66.4 ± 7.9 | .985 |

| Education (years) | 16.5 ± 2.1 | 16.7 ± 2.5 | .836 |

| Gender (females/males) | 16/2 | 20/3 | .802 |

| Perceived Stress Scale (score) | 19.2 ± 6.9 | 11.9 ± 6.4 | .001 |

Caregivers were caring for a parent (22.2%) or spouse (77.8%) with Alzheimer’s disease or fronto-temporal dementia. The RMBPC subscale scores (mean ± SD) suggested moderate severity of problems in care recipients for depression (10.4 ± 5.7), disruptive behavior (9.5 ± 6.6), memory problems (20.4 ± 7.6), and overall (40.3 ± 16.1). The RMBPC scores, indicating caregiver reaction to care recipient’s behaviors, were on average in the low to medium range for depression (10.4 ± 8.3), disruptive behavior (10.3 ± 7.0), memory problems (9.1 ± 5.3), and overall (29.7 ± 17.2).

Difference between research center assessment and EMA at home

Subjects from both groups reported no difficulties completing assessments using the PDA. The EMA compliance rate of over 85% in our sample was comparable to previous EMA studies (Cain et al., 2009) and was similar between caregivers and non-caregivers. The reasons for not completing EMA at home included skipping assessment due to caregiving duties, missing the alarm in noisy environments, and EMA device scheduling errors. There were no systematic differences in missed EMAs between the groups.

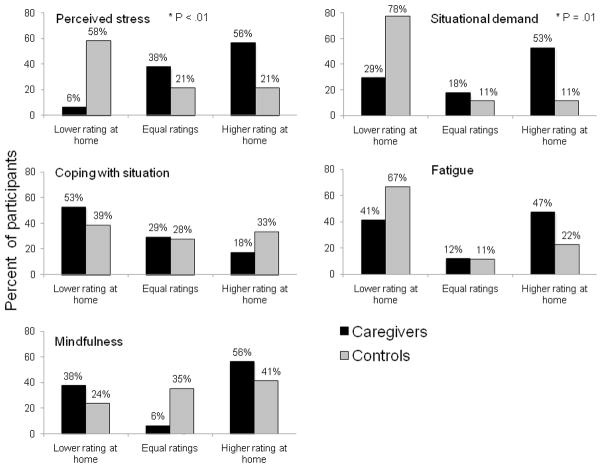

Caregivers and non-caregivers rate stress-related measures differently depending on assessment environment (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Distributions of ratings for stress-related measures based on differences between ratings obtained in the research center and home.

Patterns of scores in the two testing environments are different between caregivers and non-caregivers for ratings of perceived stress and situational demand.

All data points represent percent participants from a specific group with a certain difference pattern: 1) lower rating at home than in the research center, 2) equal ratings at home and research center, 3) higher rating at home than in the research center.

Higher scores indicate greater severity of the problem for all measures except coping with current situation.

There were significant differences between caregiver and non-caregiver groups in distributions of participants based on whether they had higher ratings for stress-related measures in the research center or at home for perceived stress, χ2 (2, N = 35) = 10.48, p < 0.01 and situational demand, χ2 (2, N = 35) = 8.90, p = 0.01. No significant group differences in distributions based on differences in ratings completed in different assessment environments emerged for ratings of fatigue, ability to cope with situation, or mindfulness, (all p’s > 0.10).

We followed these analyses with Mann-Whitney U tests to determine whether any group differences in ratings of the stress-related measures with significant Chi-Square values existed in either research center or home environments. Secondary analyses using Mann-Whitney U tests to determine any group differences in ratings were also conducted for the rest of the stress-related measures used in the study.

When tested in the research center the groups were similar on ratings for all stress-related variables (all p’s > 0.10). Only for the rating of current situational demand was there a non-significant trend suggesting that when tested in the research center non-caregivers rated the situational demand higher (mean rank of 21.03) than did caregivers (mean rank of 14.79), Z = −1.93, p = 0.07, r = 0.33. When tested at home caregivers reported greater perceived stress (mean rank of 25.47) than did non-caregivers (mean rank of 16.83), Z = −2.35, p = 0.02, r = 0.37. There was also a non-significant trend suggesting greater fatigue in caregivers (mean rank of 24.59) compared to non-caregivers (mean rank of 17.48), Z = −1.91, p = 0.058, r = 0.30. For the other measures, coping with current situation and mindfulness, there were no significant differences between caregivers and non-caregivers in any testing environment, p’s > 0.10. Information about mean values and standard deviations for all measures for both groups is reported in Table 2.

Table 2. Within and between group differences in ratings for stress-related measures in the research center and home environments.

Assessment environment differentially affects ratings for stress-related measures in caregivers and non-caregivers.

| Measure differences | Caregivers ratings | Non-caregivers ratings | Between-group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Research Center

|

At Home

|

|||||||

| Research Center | Home | pa | Research Center | Home | pa | pb | pb | |

| Perceived stress | 1.7 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 0.02* | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.02* |

| Coping with situation | 5. 6 ± 0.7 | 5.3 ± 0.7 | 0.15 | 5.1 ± 1.2 | 5.2 ± 1.2 | 1.00 | 0.30 | 0.24 |

| Mindfulness | 2.1 ± 1.4 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 0.61 | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 0.55 | 0.94 | 0.99 |

| Situational demand | 2.0 ± 0. 9 | 2.6 ± 1.0 | 0.42 | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 0.004* | 0.07T | 0.11 |

| Fatigue | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 2.8 ± 1.5 | 1.00 | 2.7 ± 1.3 | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 0.08T | 0.30 | 0.06T |

Data are presented as mean ± SD; higher ratings indicate greater severity of the problem except for the coping with situation measure.

p ≤ .025,

0.10 > p > 0.05; significant differences are in bold font

Significance level for within-group difference in ratings obtained in different testing environments using the sign test

Significance level for between- group differences in ratings obtained in same testing environment using the Mann-Whitney test

Caregivers report greater stress at home than in the research center

As expected, caregivers rated their perceived stress level higher when tested at home compared to their rating for the same measure in the research center, as indicated by the sign test, p = 0.02. There were no significant differences between ratings obtained in different testing environments for any other measures for the caregiver group.

Non-caregivers report greater situational demand in the research center than at home

Non-caregivers rated situational demand in the research center significantly greater than that at home, as indicated by the sign test, p < 0.01. There was also a non-significant trend for non-caregivers to have greater ratings for fatigue when tested in the research center than the ratings for the measure obtained at home as indicated by the sign test, p = 0.08. The effect sizes based on the sign tests for within-subjects ratings in different locations were small (r ≤ 0.08) for majority of the measures for both caregivers and non-caregivers. Only exceptions were Fatigue (r = 0.17) and Situational Demand (r = 0.32) for non-caregivers which had medium and large effect sizes, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Our results comparing self-rated stress measures among dementia caregivers and non-caregivers in two different environments confirmed our hypothesis that assessment environment differentially affects ratings for stress-related measures in caregivers and non-caregivers. We found significant interactions between a group and an assessment environment related to the fact that caregivers and non-caregivers provided similar ratings of all assessed measures when tested in the research setting, but caregivers provided higher ratings of perceived stress than non-caregivers when tested at home. Moreover, for all stress-related measures when tested in the research center, caregivers indicated similar or lower severity ratings compared to their ratings for the same measures when tested at home. This might potentially suggest that in the research center caregivers might function at a level similar or higher to their level of functioning at home. Conversely, non-caregivers on average provided lower ratings for all stress-related measures when tested at home compared to their research center ratings, potentially suggesting their overall better functioning at home.

There are several implications of our findings for clinicians and researchers working with caregiver populations. First, when caregiver current perceived stress is assessed in the clinic or research center as is often done, it may not accurately reflect their typical level of ongoing stress. The ongoing stress becomes more evident when the assessments are completed at home where the source of caregiver stress originates and persists. Therefore, assessing caregivers at home might provide a more sensitive measure of functioning. Furthermore, our results indicate that compared to being at home, a clinic or research center visit might be viewed as a more stressful experience for non-caregivers, while for caregivers a research center visit might be associated with similar or less stress than being at home. Therefore, when assessing stress-related outcomes in cross-sectional studies comparing caregivers and non-caregivers, testing in home rather than research center environment might provide a better indication of experiences that caregivers and non-caregivers have on a daily basis.

Next, our participants reported no difficulties completing EMA using a PDA after a brief training conducted during a research center visit. Despite their busy schedules caregivers in our sample demonstrated good EMA compliance during the 24-hour assessment period, suggesting that at least short-term EMA is feasible in this burdened population. Another study using EMA methods with older caregivers of ill spouses suggested that even longer assessment periods might be used (Poulin et al., 2010).

Although only a few published studies reported utilizing EMA in caregiver populations, EMA methodology has been effectively used as an alternative to retrospective recall in different populations to evaluate mood, anxiety, drug and medication use, and diet (Shiffman et al., 2008). EMA may provide a more valid way of capturing dynamic momentary experiences like stress, thoughts, and emotions that change over time than retrospective recall affected by biases (Trull and Ebner-Priemer, 2009). Retrospective recall biases might be more pronounced in older adults who have increased incidence of memory deficits (Cain et al., 2009), which makes EMA an attractive methodology in researching aging populations. Moreover, conducted in participants’ natural environment, EMA has greater ecological validity than assessments conducted in the controlled research center setting (Cain et al., 2009).

To our knowledge this is the first published study that compared differences in ratings on the same stress-related measures between the research center and home environment using EMA in caregivers and non-caregivers. However, findings indicating differences between results of psychophysiological assessments conducted at home and in the research setting have been previously reported in studies assessing depressed participants and people with bipolar disorder (Ebner-Priemer and Trull, 2009).

Although EMA appears to be a useful methodology for reporting subjective experiences in the moment; there is a paucity of research assessing how this methodology compares to objective measures of stress obtained in the research center. Due to dynamic changes in many markers of stress because of circadian variations or in response to stressful situations EMA might be an attractive way for evaluating such objective biomarkers. As suggested by several recent investigations, known stress biomarkers such as salivary hormone cortisol or salivary enzyme alpha amylase can be evaluated at multiple time points in participants’ natural environment using EMA (Matias et al., 2011, Nater et al., 2007, Robles et al., 2011). Further, physiological measures such as blood pressure have been successfully collected using EMA, and they were shown to be influenced by the environment where the readings are done (in the clinic or via ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in the natural environment) (Ebner-Priemer and Trull, 2009). Additionally, current technology also is capable of evaluating cognitive performance and evoked potentials related to completing a cognitive task utilizing EMA in participant’s natural environments (Ellingson and Oken, 2010, Fonareva et al., 2010). Further research on this topic is warranted to address utility of EMA for diverse types of measures and to further evaluate how EMA compares to obtaining similar measures in the research center environment.

Though using EMA might require substantial initial investment to pay for devices and software programming expertise, advancing technology provides powerful, versatile platforms for implementing EMA directly supporting automated data acquisition, therefore ultimately reducing personnel and other related costs while improving accuracy and reliability. Next, studies utilizing EMA, including ours, demonstrate that with proper training, presented with a user-friendly assessment interface, participants of different backgrounds and ages can complete EMA successfully.

Several limitations of study must be taken into consideration when interpreting our findings. First, while EMA have been used for various assessment periods ranging from one day to several weeks, we collected EMA at home for a single 24-hour period. It is possible using EMA for more than one day might be advantageous because the situation in caregivers’ homes might change as a result of fluctuation in care recipient’s behavior. However, because dementia caregivers are a population already pressured by many external demands, we believe using EMA for a single 24-hour period is a suitable compromise between collecting real-time data in caregivers’ natural environment and minimizing their participation burden.

Second, the stress-related measures used for EMA in our study do not comprise a validated instrument but rather were chosen based on our previous findings indicating aspects of functioning affected by caregiving and remediable by a stress-reducing intervention (Oken et al., 2010). Our goal was also to reduce the time spent completing a single assessment to less than 5 minutes. Therefore, though we were able to show that caregivers’ ratings of perceived stress and non-caregivers’ ratings of situational demand significantly differ between research center and home environments, the study might have had an insufficient power to detect significant differences in other stress-related measures of interest as indicated in the results.

Third, our study sample was relatively small, and included cognitively intact, high-functioning, well-educated, mostly female, participants who were motivated to participate in research. It is unknown how our results might generalize to populations more heterogeneous in terms of gender, cognitive health, overall functioning, and education.

Despite these limitations we believe that our findings have important implications for assessing stress in caregivers and non-caregivers. Specifically, when evaluating stress and related measures in dementia caregivers and when comparing functioning in caregivers and non-caregivers, the assessment environment appears critical, and EMA represents a feasible way of evaluating stress in natural environments for these groups.

Future studies assessing stress in caregivers and non-caregivers using EMA are needed to replicate our findings. Using longer testing periods and recruiting more heterogeneous samples might be of value. Further, in addition to collecting psychological data, it might be beneficial to evaluate EMA utility for assessing physiological data (especially measures affected by stress level) and cognitive function in natural environments for dementia caregivers and non-caregivers.

In conclusion, for clinicians and researchers working with dementia caregivers assessment location is critical when evaluating stress-related measures in this population. Conducting certain assessments at home, the environment where the source of caregivers’ stress is rooted, provides a more valid way to assess stress-related outcomes in this population and can be accomplished with EMA.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants U19AT002656, T32AT002688, K24AT005121, P30AG008017, and UL1RR024140. We thank Daniel Zajdel and Helane’ Wahbeh for help conducting the study and Andy Fish for excellent administrative support.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None.

Description of the author’s roles

Irina Fonareva collected non-caregiver data, conducted statistical analyses, and wrote the paper. Roger Ellingson implemented the EMA on the PDA, provided technical support throughout data collection period, and assisted with writing the paper. Alexandra Amen collected caregiver data and carried out statistical analyses. Barry Oken designed the study, supervised the data collection, and assisted with writing the paper.

Contributor Information

Irina Fonareva, Department of Behavioral Neuroscience, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR 97239, USA

Alexandra M. Amen, Department of Neurology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR 97239, USA

Roger M. Ellingson, Department of Neurology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR 97239, USA

Barry S. Oken, Departments of Neurology and Behavioral Neuroscience, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR 97239, USA

References

- Acton GJ, Kang J. Interventions to reduce the burden of caregiving for an adult with dementia: a meta-analysis. Research in Nursing & Health. 2001;24:349–60. doi: 10.1002/nur.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty H, Green A, Koschera A. Meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51:657–64. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain AE, Depp CA, Jeste DV. Ecological momentary assessment in aging research: a critical review. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009;43:987–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 1983;24:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner-Priemer UW, Trull TJ. Ecological momentary assessment of mood disorders and mood dysregulation. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:463–75. doi: 10.1037/a0017075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingson RM, Oken BS. Feasibility and performance evaluation of generating and recording visual evoked potentials using ambulatory Bluetooth based system. Conference Proceedings IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; 2010. pp. 6829–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonareva I, Amen AM, Zajdel DP, Ellingson RM, Oken BS. Assessing sleep architecture in dementia caregivers at home using an ambulatory polysomnographic system. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2011;24:50–9. doi: 10.1177/0891988710397548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonareva I, Ellingson RM, Zajdel DP, Amen AM, Oken BS. Measuring evoked potentials during a go-nogo reaction time task in subjects’ natural environment using an ambulatory recording system (Abstract) Psychophysiology. 2010;47:S22. [Google Scholar]

- Hoddes E, Zarcone V, Smythe H, Phillips R, Dement WC. Quantification of sleepiness: a new approach. Psychophysiology. 1973;10:431–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1973.tb00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matias GP, Nicolson NA, Freire T. Solitude and cortisol: associations with state and trait affect in daily life. Biological Psychology. 2011;86:314–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills PJ, et al. Effects of gender and dementia severity on Alzheimer’s disease caregivers’ sleep and biomarkers of coagulation and inflammation. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2009;23:605–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nater UM, Rohleder N, Schlotz W, Ehlert U, Kirschbaum C. Determinants of the diurnal course of salivary alpha-amylase. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:392–401. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oken BS, et al. Pilot controlled trial of mindfulness meditation and education for dementia caregivers. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2010;16:1031–8. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Helping caregivers of persons with dementia: which interventions work and how large are their effects? International Psychogeriatrics. 2006;18:577–95. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206003462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin MJ, et al. Does a helping hand mean a heavy heart? Helping behavior and well-being among spouse caregivers. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25:108–17. doi: 10.1037/a0018064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles TF, et al. The feasibility of ambulatory biosensor measurement of salivary alpha amylase: Relationships with self-reported and naturalistic psychological stress. Biologocal Psychology. 2011;86:50–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Martire LM. Family caregiving of persons with dementia: prevalence, health effects, and support strategies. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2004;12:240–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Sherwood PR. Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. The American Journal of Nursing. 2008;108:23–7. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336406.45248.4c. quiz 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits CH, et al. Effects of combined intervention programmes for people with dementia living at home and their caregivers: a systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;22:1181–93. doi: 10.1002/gps.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teri L, et al. Assessment of behavioral problems in dementia: the revised memory and behavior problems checklist. Psychology and Aging. 1992;7:622–31. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.4.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson CA, et al. Systematic review of information and support interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. BMC Geriatrics. 2007;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Ebner-Priemer UW. Using experience sampling methods/ecological momentary assessment (ESM/EMA) in clinical assessment and clinical research: introduction to the special section. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:457–62. doi: 10.1037/a0017653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Kanel R, Ancoli-Israel S, Dimsdale JE. Sleep and biomarkers of atherosclerosis in elderly Alzheimer caregivers and controls. Gerontology. 2010;56:41–50. doi: 10.1159/000264654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiuchi K, Yamamoto Y, Akabayashi A. Application of ecological momentary assessment in stress-related diseases. Biopsychosocial Medicine. 2008;2:13. doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]