Abstract

Objectives

People who are obese have higher demands for medical care than those of the normal weight people. However, in view of their shorter life expectancy, it is unclear whether obese people have higher lifetime medical expenditure. We examined the association between body mass index, life expectancy and lifetime medical expenditure.

Design

Prospective cohort study using individual data from the Ohsaki Cohort Study.

Setting

Miyagi Prefecture, northeastern Japan.

Participants

The 41 965 participants aged 40–79 years.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The life expectancy and lifetime medical expenditure aged from 40 years.

Results

In spite of their shorter life expectancy, obese participants might require higher medical expenditure than normal weight participants. In men aged 40 years, multiadjusted life expectancy for those who were obese participants was 41.4 years (95% CI 38.28 to 44.70), which was 1.7 years non-significantly shorter than that for normal weight participants (p=0.3184). Multiadjusted lifetime medical expenditure for obese participants was £112 858.9 (94 954.1–131 840.9), being 14.7% non-significantly higher than that for normal weight participants (p=0.1141). In women aged 40 years, multiadjusted life expectancy for those who were obese participants was 49.2 years (46.14–52.59), which was 3.1 years non-significantly shorter than for normal weight participants (p=0.0724), and multiadjusted lifetime medical expenditure was £137 765.9 (123 672.9–152 970.2), being 21.6% significantly higher (p=0.0005).

Conclusions

According to the point estimate, lifetime medical expenditure might appear to be higher for obese participants, despite their short life expectancy. With weight control, more people would enjoy their longevity with lower demands for medical care.

Article summary

Article focus

Obese people have higher needs and demands for medical care.

Obesity is associated with an increased risk of mortality.

In view of the decreased life expectancy in obese participants, it is unclear whether lifetime medical expenditure increases or decreases as a result.

Key messages

In spite of their short life expectancy, obese men and women had approximately 14.7% and 21.6% higher lifetime medical expenditure in comparison with normal weight participants, respectively.

With better weight control, more people would enjoy their longevity with lower needs and demands for medical care.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first study to have investigated the association between body mass index, life expectancy and lifetime medical expenditure calculated from individual medical expenditure and mortality data over a long period in a general population.

There was a limit to the accurate estimation of life expectancy and lifetime medical expenditure for obese participants because the Japanese population has a low prevalence of body mass index≥30.0 kg/m2.

Introduction

Obesity is closely associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and other medical problems. Previous studies have reported that obese and overweight people have higher needs and demands for medical care than normal weight people.1–5 However, it is unclear whether obese people have higher lifetime medical expenditure than those of the normal weight people because the former have a comparatively shorter life expectancy.6–10 Additionally, underweight people have a higher risk of mortality and thus also tend to have higher medical expenditure per month or per person, based on a 10-year follow-up.1 4

Although four previous studies have examined the association between obesity and lifetime medical expenditure,10–13 the results were inconsistent. One study showed that obese people had lower lifetime medical expenditure than those of the normal weight people,11 whereas the others indicated that obese people had higher lifetime medical expenditure.10 12 13 In addition, two of the four studies estimated lifetime medical expenditure from excess risk of cause-specific mortality and mean medical expenditure for the index disease.10 11 Only the other two studies calculated lifetime medical expenditure on the basis of individual medical expenditure and mortality.12 13 However, one of those studies followed up the participants for only 2 years12 and the other calculated lifetime medical expenditure for elderly participants aged 70 years or over.13 Therefore, the association between body mass index (BMI) and lifetime medical expenditure remains to be fully clarified.

We therefore conducted a 13-year prospective observation of 41 965 Japanese adults aged 40–79 years living in the community, which accrued 392 860 person-years. We examined the association between BMI and lifetime medical expenditure, based on individual medical expenditure and life table analysis.1 14–17 We collected data for survival and all medical care utilisation and costs, excluding home care services provided home health aides, nursing home care and preventive health services in participants of this cohort study.

Materials and methods

Study cohort

We used data from the Ohsaki National Health Insurance (NHI) Cohort Study.1 14 16–18 In brief, we sent a self-administered questionnaire on various lifestyle habits between October and December 1994 to all NHI beneficiaries living in the catchment area of Ohsaki Public Health Center, Miyagi Prefecture, northeastern Japan. A survey was conducted of NHI beneficiaries aged 40–79 years. Among 54 996 eligible individuals, 52 029 (95%) responded.

We excluded 776 participants who had withdrawn from the NHI before 1 January 1995, when we started the prospective collection of NHI claim files. Thus, 51 253 participants formed the study cohort. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tohoku University School of Medicine. The participants who had returned the self-administered questionnaires and had signed them were considered to have consented to participate in this study.

For the current analysis, we also excluded participants who did not provide information about body weight and height (n=3543), were at both extremes of the BMI range: lower than the 0.05th percentile for BMI (below 14.41 for men; below 13.67 for women) or higher than the 99.95th percentile for BMI (above 58.46 for men; above 62.00 for women; n=48), those who died within the first year (n=454) or those who had a history of cancer (n=1533), myocardial infarction (n=1233), stroke (n=831) or kidney disease (n=1646). Thus, a total of 41 965 participants (20 066 men and 21 899 women) participated.

Body mass index

The self-administered questionnaire included questions on weight and height, and BMI was calculated as weight divided by the square of height (kilograms per square metre). We divided the participants into groups according to the following BMI categories: <18.5 (underweight), 18.5–24.9 (normal weight), 25.0–29.9 (overweight) and ≥30.0 kg/m2 (obesity). These BMI categories correspond to the cut-off points proposed by the WHO: normal BMI range (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), grade 1 overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2), grade 2 overweight (30.0–39.9 kg/m2) and grade 3 overweight (≥40.0 kg/m2).19

The validity of self-reported body weight and height has been reported earlier.1 Briefly, the weight and height of 14 883 participants, who were a subsample of the cohort, were measured during basic health examinations provided by local governments in 1995. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) and weighted κ (κ) between the self-reported values and measured values were r=0.96 (p<0.01) for weight, r=0.93 (p<0.01) for height and r=0.88 (p<0.01) and κ=0.72 for BMI categories.

Health insurance system in Japan

The details of the NHI system have been described previously.1 4 14 16 18 Briefly, everyone living in Japan is required to enrol in one health insurance system. The NHI covers 35% of the Japanese population for almost all medical treatment, including diagnostic tests, medication, surgery, supplies and materials, physicians and other personnel costs and most dental treatment. It also covers home care services provided by physicians and nurses but not those by other professionals such as home health aides. The NHI covers inpatient care but not nursing home care. Also, it does not cover preventive health services such as mass screening and health education. Payment to medical providers is made on a fee-for-service basis, where the price of each service is determined by a uniform national fee schedule.

If a participant withdrew from the NHI system because of death, emigration or employment, the withdrawal date and the reason for withdrawal were coded in the NHI withdrawal history files. We recorded any mortality or migration by reviewing the NHI withdrawal history files and collected data on the death of participants by reviewing the death certificates filed at Ohsaki Public Health Center. We then followed up the participants and prospectively collected data on medical care utilisation and its costs for all participants in the cohort from 1 January 1995 through 31 December 2007.

Statistical analysis

We conducted the same analysis as the previous study about the association between walking, life expectancy and lifetime medical expenditure.16 Briefly, we divided the age groups (×) from 40 years according to the following categories: 40–44, 45–49, 50–54, 55–59, 60,64, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84 and ≥85 years. Based on person-years and the number of deaths from 1996 until 2007, the multiadjusted mortality rates for each age category were estimated from a Poisson regression model. The dependent variable was mortality, and independent variables were age groups, categories of BMI and the following covariates: smoking status (current and past smoker or never smoker), alcohol consumption (current drinker consuming 1–499 g/week, current drinker consuming ≥450 g/week or never and past drinker), sports and physical exercise (≥3 h/week or <3 h/week), time spent walking (≥1 h/week or <1 h/week) and education (junior high school, high school or college/university or higher). We did not adjust for hypertension and diabetes mellitus in the multivariate models because these variables are considered to occupy an intermediate position in the etiologic pathway between BMI and mortality.

We separately calculated medical expenditure for participants who survived through the index year and for those who died because previous study showed that medical expenditure increased before death.20 The multiadjusted medical expenditure per year was estimated using a linear regression model adjusted for the above covariates in survivors and decedents.

The estimates of multiadjusted mortality and medical expenditure were used for estimating life expectancy and lifetime medical expenditure from 40 years of age. To estimate life expectancy and lifetime medical expenditure, we constructed life tables per 100 000 persons using Chiang's analytical method on the basis of the latest published complete life tables of Japan for the year 2000.21 22 Then, life expectancy (ex) and lifetime medical expenditure (Mx) for each age groups (x) were estimated using the numbers of survivors (lx), deaths (dx), static population (Lx), multiadjusted medical expenditure for survivors (ay) and multiadjusted medical expenditure for the deceased (by) as follows:

The 95% CIs were estimated using a Monte Carlo simulation based on a Poisson regression model and linear regression model. We repeated 100 000 times, and all analysis were used the SAS V.9.1 statistical software package (SAS Institute Inc., 2004). All p values <0.05 were accepted as statistically significant.

We used a purchasing power parity rate of UK£ 1.00= JPN\140.16

Results

After 13 years of follow-up, we observed 5159 deaths (3356 men and 1803 women) among the 41 965 participants (20 066 men and 21 899 women).

The mean medical expenditure per year for survivors in men was £2393 in underweight, £2055 in normal weight, £2231 in overweight and £2334 in obesity, respectively. In women, it was £2375 in underweight, £1972 in normal weight, £2317 in overweight and £2733 in obesity, respectively. These differences of mean medical expenditure per year for survivors are statistically significant in men and women (ANOVA; p<0.0001). Also, the mean medical expenditure in the year of death for participants in men was £15 445 in underweight, £16 973 in normal weight, £17 811 in overweight and £17 878 in obesity, respectively. In women, it was £12 833 in underweight, £15 584 in normal weight, £17 059 in overweight and £19 635 in obesity, respectively. These differences of mean medical expenditure in the year of death for participants are statistically significant in only women (men, p=0.2241; women, p=0.0059).

Baseline characteristics by BMI category

The baseline characteristics of the study participants according to the BMI categories are shown for men and women (table 1), among whom 3.3% and 3.9% were underweight, 23.6% and 28.4% were overweight and 2.0% and 3.6% were obese, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by BMI categories in 41 965 participants

| Men |

Women |

|||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) |

p Value* | BMI (kg/m2) |

p Value | |||||||

| <18.5 | 18.5–24.9 | 25.0–29.9 | ≥30.0 | <18.5 | 18.5–24.9 | 25.0–29.9 | ≥30.0 | |||

| No. of subjects | 666 | 14 278 | 4730 | 392 | <0.0001 | 857 | 14 031 | 6226 | 785 | <0.0001 |

| Mean age (years) | 64.0 | 59.1 | 57.4 | 56.1 | 63.7 | 59.8 | 60.7 | 61.2 | ||

| SD | 10.4 | 10.5 | 10.2 | 10.2 | 10.9 | 10.1 | 9.1 | 9.5 | ||

| Smoking status (%) | ||||||||||

| Current and past smoker | 87.3 | 82.5 | 76.6 | 74.8 | <0.0001 | 18.6 | 11.2 | 10.1 | 10.6 | <0.0001 |

| Never smoker | 12.7 | 17.5 | 23.4 | 25.2 | 81.4 | 88.8 | 90.0 | 89.4 | ||

| Alcohol consumption (%) | ||||||||||

| Current drinker, 1–449 g/week | 49.2 | 61.0 | 61.4 | 50.8 | <0.0001 | 18.2 | 21.8 | 21.4 | 19.3 | 0.0574 |

| Current drinker, ≥450 g/week | 9.6 | 11.7 | 12.6 | 15.0 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.9 | ||

| Never and past drinker | 41.2 | 27.3 | 26.0 | 34.2 | 81.2 | 77.4 | 78.2 | 79.8 | ||

| Sports and physical exercise (%) | ||||||||||

| ≥3 h/week | 17.5 | 16.1 | 13.8 | 10.1 | <0.0001 | 9.8 | 11.3 | 11.0 | 10.8 | 0.5993 |

| <3 h/week | 82.5 | 83.9 | 86.2 | 89.9 | 90.2 | 88.7 | 89.0 | 89.2 | ||

| Time spent walking (%) | ||||||||||

| ≥1 h/day | 41.7 | 51.4 | 45.8 | 42.7 | <0.0001 | 37.9 | 45.1 | 41.0 | 35.6 | <0.0001 |

| <1 h/day | 58.3 | 48.7 | 54.2 | 57.3 | 62.1 | 54.9 | 59.0 | 64.4 | ||

| Education (%) | ||||||||||

| Junior high school | 64.2 | 62.2 | 58.9 | 58.8 | 0.0013 | 58.3 | 54.2 | 62.7 | 71.3 | <0.0001 |

| High school | 27.4 | 30.5 | 33.4 | 33.4 | 34.0 | 36.9 | 31.0 | 24.6 | ||

| College/university or higher | 8.4 | 7.3 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 8.9 | 6.3 | 4.1 | ||

p Values were calculated by χ2 test (categorical variables) or ANOVA (continuous variables).

BMI, body mass index.

Mean age in men decreased linearly with increasing BMI category. In women, mean age was highest in the underweight category. The proportions of men and women who were current and past smokers decreased with increasing BMI, and this tendency was especially marked in men. The proportions of men who had never and past drinker were highest in the underweight category. The proportions of men who did ≥3 h sports and physical exercise per week decreased with increasing BMI. The proportions of men and women who walked ≥1 h/day were the lowest in underweight men and obese women. Educational background increased linearly in men and decreased linearly in women as the BMI category increased. These characteristics showed statistically significant difference.

Mortality in terms of categories for BMI

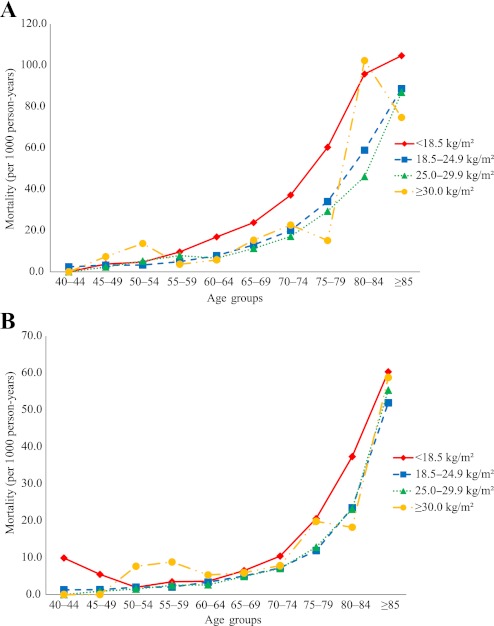

Figure 1A for men and figure 1B for women show the mortality (per 1000 person-years) in each of the age groups according to the categories of BMI.

Figure 1.

Multiadjusted mortality by BMI categories in each age group in men (A) and women (B).

In underweight participants, there was a tendency that the mortality was the highest in each age group. Overweight participants showed similar mortality with normal weight participants, especially women. Overweight men showed slightly lower mortality than normal weight men. In obese participants, the mortality curve was not described smoothly because of small number of participants.

Table 2 shows the mortality ratio with 95% CIs according to the categories of BMI. In underweight participants, the multiadjusted mortality ratio was significantly higher than that in the normal weight participants (men, 1.62, 95% CI 1.41 to 1.86, p<0.0001; women, 1.46, 1.22 to 1.76, p<0.0001). In overweight participants, the multiadjusted mortality ratio was significantly lower in men and non-significantly lower in women than that in normal weight participants (men, 0.91, 0.83 to 0.99, p=0.0260; women, 0.98, 0.88 to 1.10, p=0.7841). In obese participants, the multiadjusted mortality ratio was non-significantly higher than that in normal weight participants (men, 1.14, 0.88 to 1.49, p=0.3177; women, 1.23, 0.98 to 1.55, p=0.0717).

Table 2.

Mortality ratio for BMI categories in 41 965 participants

| BMI (kg/m2) | Univariate |

Multiadjusted* |

||

| Mortality ratio (95% CI) | p Value | Mortality ratio (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Men | ||||

| <18.5 | 1.69 (1.47 to 1.93) | <0.0001 | 1.62 (1.41 to 1.86) | <0.0001 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| 25.0–29.9 | 0.90 (0.82 to 0.98) | 0.0163 | 0.91 (0.83 to 0.99) | 0.0260 |

| ≥30.0 | 1.13 (0.87 to 1.47) | 0.3712 | 1.14 (0.88 to 1.49) | 0.3177 |

| Women | ||||

| <18.5 | 1.50 (1.25 to 1.81) | <0.0001 | 1.46 (1.22 to 1.76) | <0.0001 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| 25.0–29.9 | 1.00 (0.89 to 1.11) | 0.9613 | 0.98 (0.88 to 1.10) | 0.7841 |

| ≥30.0 | 1.29 (1.03 to 1.62) | 0.0273 | 1.23 (0.98 to 1.55) | 0.0717 |

Adjusted for age groups, smoking status, alcohol drinking, sports and physical exercise, time spent walking and education.

BMI, body mass index.

Life expectancy and lifetime medical expenditure by BMI category

Table 3 shows life expectancy and lifetime medical expenditure with 95% CIs according to the BMI categories.

Table 3.

Life expectancy and lifetime medical expenditure at age 40 years for BMI categories in 41 965 participants

| BMI (kg/m2) | Univariate |

Multiadjusted* |

||||

| Estimate | 95% CI | p Value | Estimate | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Men | ||||||

| Life expectancy at age 40 years (years) | ||||||

| <18.5 | 36.72 | 35.10 to 38.17 | <0.0001 | 37.40 | 35.80 to 38.87 | <0.0001 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 42.70 | 41.91 to 43.37 | Reference | 43.03 | 42.22 to 43.73 | Reference |

| 25.0–29.9 | 44.09 | 42.89 to 45.25 | 0.0157 | 44.34 | 43.11 to 45.54 | 0.0264 |

| ≥30.0 | 41.23 | 38.16 to 44.54 | 0.3733 | 41.36 | 38.28 to 44.70 | 0.3184 |

| Lifetime medical expenditure at age 40 years (£) | ||||||

| <18.5 | 94 877.5 | 83 411.4 to 106 275.7 | 0.6846 | 93 208.7 | 81 704.9 to 104 706.4 | 0.3916 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 97 244.1 | 92 662.5 to 101 774.0 | Reference | 98 355.0 | 93 165.3 to 103 010.2 | Reference |

| 25.0–29.9 | 114 398.2 | 107 490.1 to 121 505.3 | <0.0001 | 114 766.9 | 107 754.1 to 121 966.6 | <0.0001 |

| ≥30.3 | 115 362.6 | 97 361.8 to 134 555.0 | 0.0501 | 112 858.9 | 94 954.1 to 131 840.9 | 0.01141 |

| Women | ||||||

| Life expectancy at age 40 years (years) | ||||||

| <18.5 | 46.26 | 43.98 to 48.43 | <0.0001 | 46.98 | 44.63 to 49.29 | <0.0001 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 51.70 | 50.28 to 53.02 | Reference | 52.31 | 50.79 to 53.75 | Reference |

| 25.0–29.9 | 51.74 | 49.98 to 53.48 | 0.9582 | 52.56 | 50.67 to 54.46 | 0.7797 |

| ≥30.0 | 48.13 | 45.23 to 51.22 | 0.0272 | 49.23 | 46.14 to 52.59 | 0.0724 |

| Lifetime medical expenditure at age 40 years (£) | ||||||

| <18.5 | 108 278.3 | 97 142.8 to 119 593.7 | 0.5816 | 109 382.2 | 97 996.6 to 121 008.6 | 0.5174 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 111 512.8 | 105 303.4 to 117 910.4 | Reference | 113 282.9 | 106 668.0 to 120 054.6 | Reference |

| 25.0–29.9 | 127 869.3 | 120 236.3 to 135 932.3 | <0.0001 | 129 964.6 | 121 845.4 to 138 577.2 | <0.0001 |

| ≥30.0 | 134 887.1 | 121 318.4 to 149 383.6 | 0.0007 | 137 765.9 | 123 672.9 to 152 970.2 | 0.0005 |

Adjusted for age groups, smoking status, alcohol drinking, sports and physical exercise, time spent walking and education.

BMI, body mass index.

By multiadjusted analysis, obese men and women had approximately 1.7 and 3.1 years non-significantly shorter life expectancy from the age of 40 years in comparison with men and women of normal weight, respectively (men, p=0.3184; women, p=0.0724). Meanwhile, obese men and women had approximately 14.7% non-significantly higher and 21.6% significantly higher lifetime medical expenditure in comparison with normal weight participants, respectively (men, p=0.1141; women, p=0.0005).

In men, multiadjusted life expectancy was greatest for overweight, that is, 44.34 years (95% CI 43.11 to 45.54, p=0.0264), followed by normal weight (43.03 years, 42.22 to 43.73) and obesity (41.36 years, 38.28 to 44.70, p=0.3184) and was shortest for underweight (37.40 years, 35.80 to 38.87, p<0.0001). The multiadjusted lifetime medical expenditure for overweight was the highest, that is, £114 766.9 (95% CI 107 754.1 to 121 966.6, p<0.0001), followed by obesity (£112 858.9, 94 954.1 to 131 840.9, p=0.1141) and normal weight (£98 355.0, 93 615.3 to 103 010.2) and was the lowest for underweight (£93 208.7, 81 704.9 to 104 706.4, p=0.3916).

In women, multiadjusted life expectancy was greatest for overweight, that is, 52.56 years (50.67 to 54.46, p=0.7797), followed by normal weight (52.31 years, 50.79 to 53.75) and obesity (49.23 years, 46.14 to 52.59, p=0.0724) and was shortest for underweight (46.98 years, 44.63 to 49.29, p<0.0001). The lifetime medical expenditure for obesity was the highest (£137 765.9, 123 672.9 to 152 970.2, p=0.0005), followed by overweight (£129 964.6, 121 845.4 to 138 577.2, p<0.0001) and normal weight (£113 282.9, 106 668.0 to 120 054.6) and was lowest for underweight (£109 382.2, 97 996.6 to 121 008.6, p=0.5174).

Discussion

The present results indicate that (1) obese men and women have 14.7% non-significantly higher and 21.6% significantly higher multiadjusted lifetime medical expenditure than those of the normal weight participants (men, p=0.1141; women, p=0.0005), even though their life expectancy is non-significantly shorter by 1.7 and 3.1 years than those of the normal weight participants, respectively (men, p=0.3184; women, p=0.0724); (2) underweight men and women have 5.2% and 3.4% non-significantly lower lifetime medical expenditure than those of the normal weight participants (men, p=0.5174; women, p=0.3916) because men and women live 5.6 and 5.3 years significantly less than those of the normal weight participants, respectively (men, p<0.0001; women, p<0.0001).

Comparison with other studies

Obese participants had shorter life expectancy than normal weight participants, as has been observed in previous studies.6–10 Overweight participants had longer life expectancy than normal weight participants. Two of the four previous studies have reported that overweight participants had longer life expectancy than normal weight participants.7 9 These results support our finding of an association between being overweight and life expectancy. Additionally, an association between BMI and all-cause mortality in the Japanese population has been reported by other data sets.23–29 All seven previous studies showed that among the BMI categories, the lowest one had the highest mortality risk. These results are consistent with the fact that underweight participants have significantly the shortest life expectancy, as was observed in our study.

Thus, the association between BMI and life expectancy showed same trend with the pooled analyses of the association between BMI and all-cause mortality in Asia and Japan.30 31

Our present results support three of the four previous studies of lifetime medical expenditure for obese participants.10 12 13 In comparison to previous studies, we calculated lifetime medical expenditure from individual medical expenditure and survival data covering longest follow-up period to date. Meanwhile, one study has shown that obese participants have lower lifetime medical expenditure than normal weight participants.11 However, that study limited the participants to non-smokers and calculated lifetime medical expenditure from the mortality of a hypothetical cohort and estimated medical expenditure from other cohort. In the present study, overweight participants were found to have higher lifetime medical expenditure than normal weight participants, as had been reported previously.10 12 13 We consider that this was attributable to the higher medical expenditure per month or per person from the 10-year or 9-year follow-up than for normal weight participants.1 3 4 On the other hand, with regard to underweight participants, our present findings were inconsistent with those of a previous study that examined the association between being underweight and lifetime medical expenditure.13 However, that study calculated lifetime medical expenditure for elderly participants aged over 70 years. Elderly underweight participants have high mortality,32 and medical expenditure increases in the 1 year prior to death.20 Thus, lifetime medical expenditure from 70 years for underweight participants becomes higher than for participants of normal weight. Our study results are thus inconsistent with those reported previously.

We previously calculated life expectancy and lifetime medical expenditure for smokers and non-smokers from age 40 years by using the same data set as that for the present study.17 The results indicated that lifetime medical expenditure was non-significantly lower in smokers than in non-smokers, reflecting the 3.5 years shorter life expectancy of smokers. On the other hand, the present study indicated that lifetime medical expenditure was higher for obese participants in spite of their shorter life expectancy. This difference would result from the difference in which obesity and smoking affect one's health and longevity. Previous studies of healthy and disability free life expectancy have agreed that smoking shortens life expectancy without affecting the years of life spent with ill-health or disability, while obesity shortens life expectancy and extends the years of life with ill-health or disability.33 On the basis of these differences, Reuser et al summarised the situation as ‘smoking kills and obesity disables’.7 Extended years with ill-health and/or disability must result in increased lifetime medical expenditure. All these findings suggest that weight control would bring about longer life expectancy and long-term enhancement of the quality of life and a cost saving.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of our present study is that it is the first in the world to have clarified the association between BMI and lifetime medical expenditure calculated from individual medical expenditure and mortality data over a long period in a general population from the age of 40 years.1 14 16–18 The NHI covers almost all medical care utilisation.1 4 14 16 18 Additionally, in order to reduce bias, we adjusted confounders by including various covariates in our Poisson regression model and linear regression mode.16 On the other hand, several limitations of our study should also be considered. First, we used self-reported BMI which in a source of error.34 35 We consider this error to be a non-differential misclassification. This misclassification would lead to attenuation of the true association towards the null. To address this problem, van Dam et al36 studied the association between BMI and mortality using lower BMI cut-off points: 24.5 kg/m2 to reflect a measured BMI of 25.0 kg/m2 and 29.0 kg/m2 to reflect a measured BMI of 30.0 kg/m2. The association showed similar with original cut-off points. Second, the 95% CI was wide, and there was a limit to the accurate estimation of life expectancy and lifetime medical expenditure for obese participants. Additionally, we did not observe significant association in obese participants without lifetime medical expenditure in women. However, our results are consistent with those of the previous studies.6–8 10 12 13 In Japan, prevalence of obesity is only 3%.37 Thus, the reason for non-significant association might be β error because of the lack of statistical power due to small number of obese participants.

Conclusions and policy implication

In summary, even though we observed non-significant association between obesity, life expectancy and lifetime medical expenditure without lifetime medical expenditure in women, lifetime medical expenditure might appear to be higher for obese participants, despite their short life expectancy. With better weight control, more people would enjoy their longevity with lower needs and demands for medical care.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Nagai M, Kuriyama S, Kakizaki M, et al. Impact of obesity, overweight and underweight on life expectancy and lifetime medical expenditures: the Ohsaki Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000940. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000940

Contributors: All authors contributed to the design of the study. MN, SK, MK, KO-M, TS and IT participated in data collection. MN, SK, AH, MK and SH participated in data analysis. MN, MK, KO-M, TS, AH, MK and SH participated in the writing of the report. SK and IT participated in critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the report for submission.

Funding: This study was supported by a Health Sciences Research Grant for Health Services (H21-Choju-Ippan-001, H20-Junkankitou (Seisyu)-Ippan-013, H22-Junkankitou (Seisyu)-Ippan-012), Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan. MN is a recipient of a Research Fellowships of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tohoku University School of Medicine. Participants who had returned the self-administered questionnaires and signed them were considered to have consented to participate.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.Kuriyama S, Tsuji I, Ohkubo T, et al. Medical care expenditure associated with body mass index in Japan: the Ohsaki Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002;26:1069–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Detournay B, Fagnani F, Phillippo M, et al. Obesity morbidity and health care costs in France: an analysis of the 1991-1992 Medical Care Household Survey. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000;24:151–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson D, Brown JB, Nichols GA, et al. Body mass index and future healthcare costs: a retrospective cohort study. Obes Res 2001;9:210–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakamura K, Okamura T, Kanda H, et al. ; Health Promotion Research Committee of the Shiga National Health Insurance Organizations Medical costs of obese Japanese: a 10-year follow-up study of National Health Insurance in Shiga, Japan. Eur J Public Health 2007;17:424–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quesenberry CP, Jr, Caan B, Jacobson A. Obesity, health services use, and health care costs among members of a health maintenance organization. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:466–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peeters A, Barendregt JJ, Willekens F, et al. ; NEDCOM, the Netherlands Epidemiology and Demography Compression of Morbidity Research Group Obesity in adulthood and its consequences for life expectancy: a life-table analysis. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:24–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reuser M, Bonneux LG, Willekens FJ. Smoking kills, obesity disables: a multistate approach of the US Health and Retirement Survey. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:783–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Baal PH, Hoogenveen RT, de Wit GA, et al. Estimating health-adjusted life expectancy conditional on risk factors: results for smoking and obesity. Popul Health Metr 2006;4:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reuser M, Bonneux L, Willekens F. The burden of mortality of obesity at middle and old age is small. A life table analysis of the US Health and Retirement Survey. Eur J Epidemiol 2008;23:601–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson D, Edelsberg J, Colditz GA, et al. Lifetime health and economic consequences of obesity. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:2177–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Baal PH, Polder JJ, de Wit GA, et al. Lifetime medical costs of obesity: prevention no cure for increasing health expenditure. PLoS Med 2008;5:e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Brown DS, et al. The lifetime medical cost burden of overweight and obesity: implications for obesity prevention. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1843–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lakdawalla DN, Goldman DP, Shang B. The health and cost consequences of obesity among the future elderly. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(Suppl 2):W5R30–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuji I, Nishino Y, Ohkubo T, et al. A prospective cohort study on National Health Insurance beneficiaries in Ohsaki, Miyagi Prefecture, Japan: study design, profiles of the subjects and medical cost during the first year. J Epidemiol 1998;8:258–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuriyama S, Shimazu T, Ohmori K, et al. Green tea consumption and mortality due to cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all causes in Japan: the Ohsaki study. JAMA 2006;296:1255–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagai M, Kuriyama S, Kakizaki M, et al. Impact of walking on life expectancy and lifetime medical expenditure: the Ohsaki Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayashida K, Imanaka Y, Murakami G, et al. Difference in lifetime medical expenditures between male smokers and non-smokers. Health Policy 2010;94:84–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsuji I, Takahashi K, Nishino Y, et al. Impact of walking upon medical care expenditure in Japan: the Ohsaki Cohort Study. Int J Epidemiol 2003;32:809–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization The use and interpretation of anthropometry: report of a WHO expert committee. WHO Tech Rep Ser 1995;854:312–409 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breyer F, Felder S. Life expectancy and health care expenditures: a new calculation for Germany using the costs of dying. Health Policy 2006;75:178–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiang CL. The Life Table and Its Applications. Malabar, FL, USA: Krieger Publishing Company, 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Statistics and Information Department Minister's Secretariat, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan The 20th Life Tables. Tokyo, Japan: Health and Welfare Statstics Association, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayashi R, Iwasaki M, Otani T, et al. Body mass index and mortality in a middle-aged Japanese cohort. J Epidemiol 2005;15:70–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hozawa A, Okamura T, Oki I, et al. Relationship between BMI and all-cause mortality in Japan: NIPPON DATA80. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1714–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuriyama S, Ohmori K, Miura C, et al. Body mass index and mortality in Japan: the Miyagi cohort study. J Epidemiol 2004;14(Suppl 1):S33–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuo T, Sairenchi T, Iso H, et al. Age- and gender-specific BMI in terms of the lowest mortality in Japanese general population. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:2348–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyazaki M, Babazono A, Ishii T, et al. Effects of low body mass index and smoking on all-cause mortality among middle-aged and elderly Japanese. J Epidemiol 2002;12:40–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamakoshi A, Yatsuya H, Lin Y, et al. BMI and all-cause mortality among Japanese older adults: findings from the Japan collaborative cohort study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:362–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsugane S, Sasaki S, Tsubono Y. Under- and overweight impact on mortality among middle-aged Japanese men and women: a 10-y follow-up of JPHC study cohort I. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002;26:529–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng W, McLerran DF, Rolland B, et al. Association between body-mass index and risk of death in more than 1 million Asians. N Engl J Med 2011;364:719–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sasazuki S, Inoue M, Tsuji I, et al. ; Research Group for the Development and Evaluation of Cancer Prevention Strategies in Japan Body mass index and mortality from all causes and major causes in Japanese: results of a pooled analysis of 7 large-scale cohort studies. J Epidemiol 2011;21:417–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grabowski DC, Ellis JE. High body mass index does not predict mortality in older people: analysis of the Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49:968–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LaCroix AZ, Guralnik JM, Berkman LF, et al. Maintaining mobility in late life. II. Smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and body mass index. Am J Epidemiol 1993;137:858–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niedhammer I, Bugel I, Bonenfant S, et al. Validity of self-reported weight and height in the French GAZEL cohort. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000;24:1111–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gillum RF, Sempos CT. Ethnic variation in validity of classification of overweight and obesity using self-reported weight and height in American women and men: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutr J 2005;4:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Dam RM, Willett WC, Manson JE, et al. The relationship between overweight in adolescence and premature death in women. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:91–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshiike N, Matsumura Y, Zaman MM, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of body mass index in Japanese adults in a representative sample from the National Nutrition Survey 1990-1994. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1998;22:684–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.