Abstract

Background

Prior research has documented factors associated with non-traumatic dental condition (NTDC) visits to emergency departments (EDs), but little is known about the care received by patients in EDs for NTDC visits.

Objective

We examined national trends in prescription of analgesics and antibiotics in EDs for NTDC visits in the United States.

Research Design

We analyzed data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care survey for 1997 to 2007. We used a multivariable logistic regression model to examine factors associated with receiving analgesics and antibiotics for NTDC visit in EDs.

Results

Overall 74% received at least one analgesic, 56% at least one antibiotic and 13% received no medication at all during an NTDC visit to the ED. The prescription of medications at EDs for NTDC visits steadily increased over time for analgesics (OR=1.11/year, p=<.0001) and antibiotics (OR=1.06/year, p<0.0001). In the multivariable analysis, self-pay patients had significantly higher adjusted odds of receiving antibiotics, while those with non-dental reason for visit and children (0–4 years) had significantly lower adjusted odds of receiving a prescription for antibiotics in EDs for NTDC visits. Children 0–4 years, adults 53–72 years and older adults (73 years and older) had lower adjusted odds (p<0.001) of receiving analgesics.

Conclusions

Nationally, analgesic and antibiotic prescriptions for NTDC visits to EDs have increased substantially over time. Self-pay patients had significantly higher odds of being prescribed antibiotics. Adults over 53 years and especially those 73 years and older had significantly lower odds of receiving analgesics in EDs for NTDC visits.

Keywords: Nontraumatic dental conditions, Emergency Department, Medications

INTRODUCTION

The Federal Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act passed by congress in 1986 made it mandatory that all patients presenting to emergency departments be provided a minimal level of care regardless of their ability to pay.1,2 Emergency departments (EDs) therefore play a vital role in our health care system and act as the ‘provider of last resort’ for millions of under- and uninsured patients who lack adequate access to dental and medical care.3,4 Okunseri et al. reported that male and middle-aged Medicaid enrollees were significantly more likely to be frequent users of EDs for treatment of non-traumatic dental conditions (NTDCs).5 Nonetheless, empirical data to illustrate the care which patients receive in EDs for NTDC visits remain largely unclear.

Anecdotal reports suggest that treatments for NTDCs in EDs are usually palliative in nature, with patients receiving prescriptions for analgesics and antibiotics as treatment for symptoms like pain/toothache and infection. In addition, most patients receive a referral to a dental provider for follow-up care.5–7 Definitive management of acute dental conditions primarily involves extraction of teeth or extirpation of the pulp,8 as well as the use of antibiotics and analgesics where necessary.9 The prescription of antibiotics and analgesics for NTDC visits in EDs should be done with caution due to the potential for allergic reactions, toxicity, and the possibility of promoting antibiotic resistance/intolerance.9–11 Dodd and Graham published three case reports on inappropriate and unintentional overdose in the prescription of analgesics for dental pain in EDs in the United Kingdom.12 In our study, we examined patient characteristics, trends and factors associated with prescribing analgesics and antibiotics in EDs for NTDC visits within the United States.

METHODS

We analyzed data from the Emergency Department component of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) for 1997–2007. The NHAMCS uses a multi-stage cluster-sampling design based on patient encounters nested within hospitals nested within geographic areas. However, the original clustering variables are not released for data analysis beyond 2003. Instead, blinded stratification, primary clustering level, and weight variables are provided. The basic sampling unit is patient visit; therefore multiple visits by the same patient cannot be identified. NHAMCS data is collected in accordance with the privacy guidelines of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Patients who made NTDC visits were identified by the physician primary discharge diagnosis codes assigned based on the International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). The selected ICD-9-CM codes used in this study are identical to those used by Okunseri et al.5 and other published studies that have investigated NTDC visits to emergency departments. Medications were categorized into therapeutic classes using NHAMCS’s coding based on the National Drug Code Directory system. Based on the medication list recorded in the database, we created indicators for each subject showing whether that subject received any medication, antibiotic or analgesic.

Statistical Analyses

We performed descriptive statistics and used multivariable logistic regression to examine factors associated with receiving any medication, analgesics or antibiotics during an NTDC visit to an ED. Age was categorized into 6 groups, with cut-offs chosen to approximate the lower and upper 10th and 25th quantiles, and the median in the entire population. Based on findings from the descriptive statistics, calendar year was treated as a linear continuous predictor in the multivariable analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS© software Version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC), with the primary model fitted using Proc Surveylogistic. Sample estimates were weighted to provide national estimates reflective of the complex sampling scheme of NHAMCS using the provided blinded stratification and clustering variable. Multiple imputation methodology as implemented in Proc MI and MiAnalyze to incorporate observations with missing payer type (7.1% of observations) and/or ethnicity (10.3%) was used. The first five datasets were generated using a discriminant function based on year, age, sex, and sampling weight for imputing payer type, then logistic regression imputation based on year, age, sex, race, payer type, reason for visit and sampling weight was used for Hispanic ethnicity. An alpha level of 0.05 was used throughout to denote statistical significance. The study was approved by the Marquette University Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

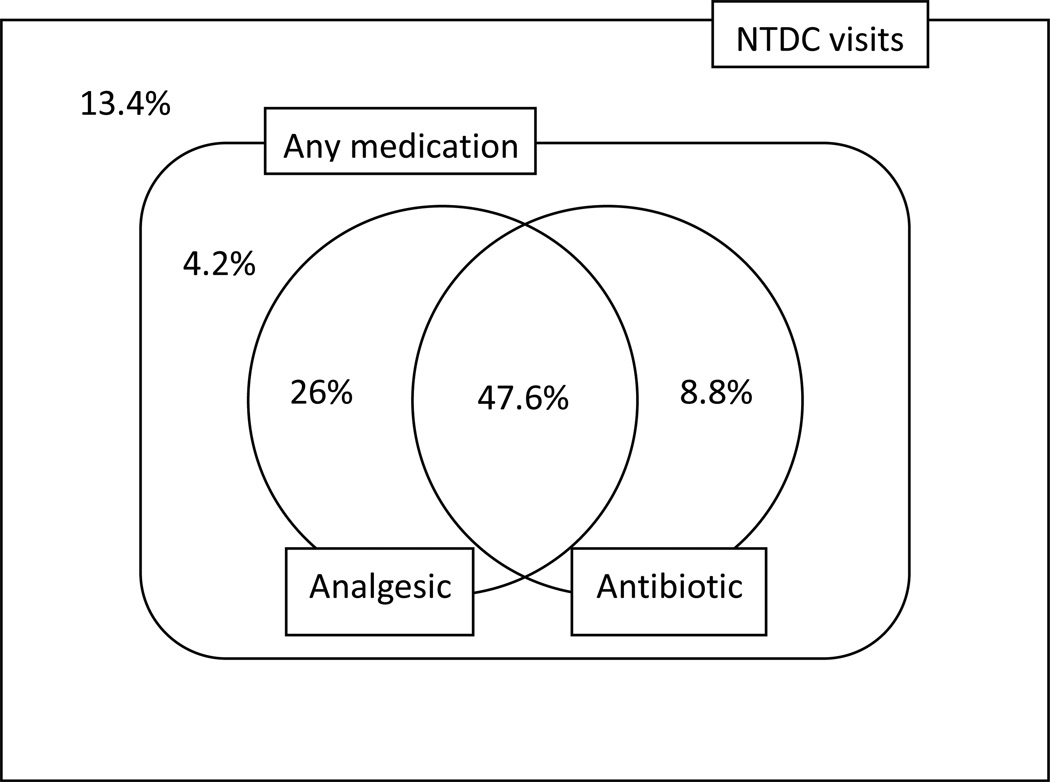

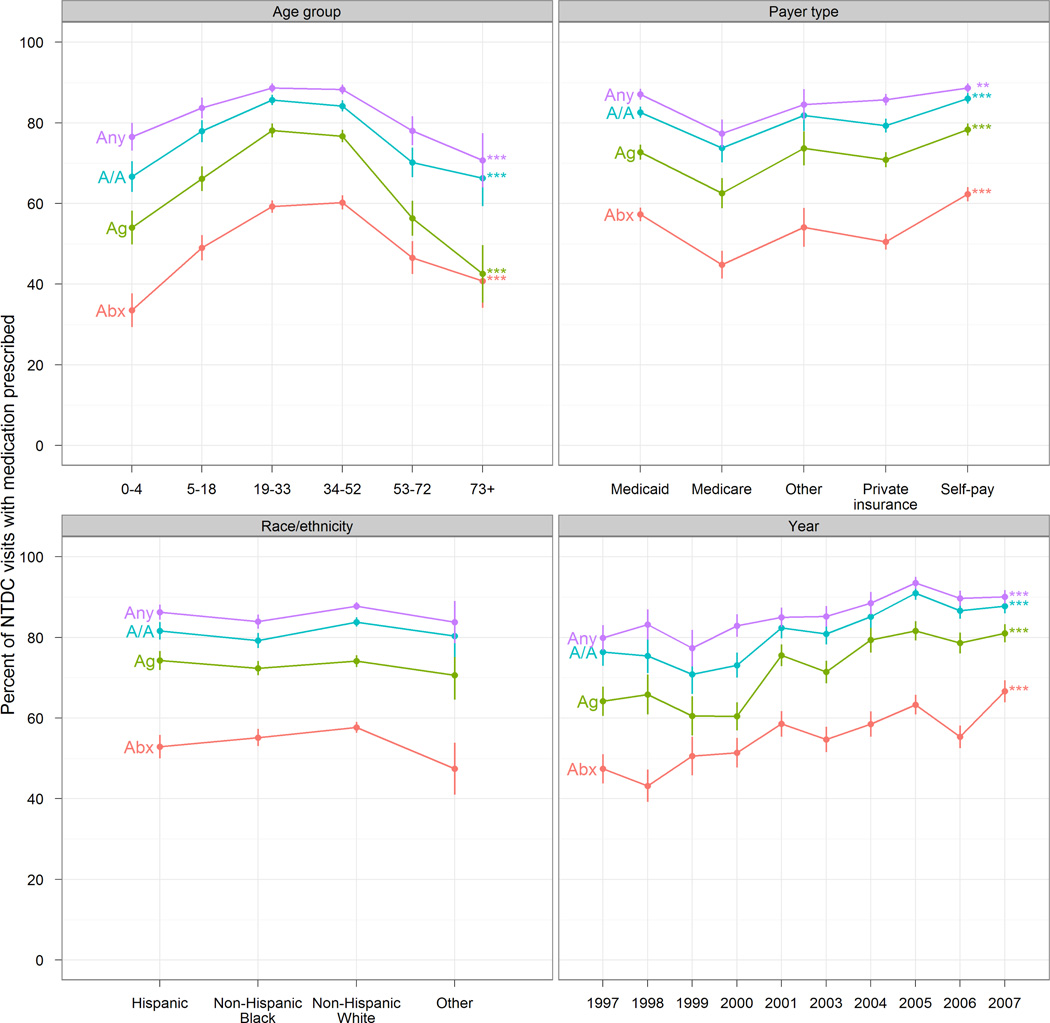

A total of 4,726 records representing 16,379,580 NTDC visits were analyzed, and the drugs prescribed were categorized as analgesics, antibiotics, or other medication. Summary statistics for the study population are presented in Table 1, including weighted frequency. Approximately 48% of the study population was aged 19–33 years old, 27% had Medicaid and 58% were whites. Figure 1 is a Venn diagram of the study population by medication received from 1997–2007. Overall, 74% of the study population received at least one analgesic and 56% at least one antibiotic during an NTDC visit to the ED, while 4% received only other medication types and 13% received no medication at all. The proportion of patients receiving analgesic and antibiotic prescriptions increased over time (from 64% to 81% and from 47% to 67%, respectively), as did the overall proportion of patients with any medication prescribed (from 80% to 90%). There appeared to be some stabilization from 2004, except that the increase in antibiotic prescriptions persisted during that period (Figure 2). The prescription of other medications in addition to analgesics and antibiotics followed similar trend patterns by age, and subjects 19–52 years old had the highest percentage of such prescriptions. The only notable deviation appeared among older adults (73 years and older) who received analgesics less often and antibiotics more often than the overall pattern would suggest.

Table 1.

Summary Statistics for the Study Population with NTDC visits: 1997–2007

| Predictor | Category | Frequency | Weighted frequency | Percent (SE)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | 0–4 years | 252 | 797,910 | 4.9 (0.4) |

| 05–18 years | 434 | 1,491,261 | 9.1 (0.5) | |

| 19–33 years | 2,196 | 7,814,721 | 47.7 (1.1) | |

| 34–52 years | 1,482 | 5,072,105 | 31.0 (0.9) | |

| 53–72 years | 278 | 912,716 | 5.6 (0.4) | |

| 73 years and older | 84 | 291,317 | 1.8 (0.2) | |

| Payer type | Private insurance | 1,175 | 4,155,407 | 25.4 (0.9) |

| Medicare | 271 | 946,619 | 5.8 (0.4) | |

| Medicaid | 1,313 | 4,383,148 | 26.8 (0.9) | |

| Self-pay | 1,471 | 5,281,433 | 32.2 (1.0) | |

| Other | 161 | 493981 | 3.0 (0.3) | |

| Unknown | 335 | 1,118,992 | 6.8 (0.7) | |

| Race/ethnicity | Non-Hispanic White | 2,590 | 9,128,395 | 55.7 (1.5) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1,066 | 3,477,355 | 21.2 (1.1) | |

| Hispanic | 481 | 1,439,884 | 8.8 (0.7) | |

| Other | 102 | 334,403 | 2.0 (0.3) | |

| Unknown ethnicity | 487 | 1,999,543 | 12.2 (1.0) | |

| Reason for visit | Non-dental reason | 1,799 | 5,998,321 | 36.6 (1.0) |

| Dental reason | 2,927 | 10,381,259 | 63.4 (1.0) | |

| Sex | Female | 2,479 | 8,831,247 | 53.9 (0.9) |

| Male | 2,247 | 7,548,333 | 46.1 (0.9) | |

| Year | 1997 | 241 | 1,018,804 | 6.2 (0.7) |

| 1998 | 240 | 991,417 | 6.1 (0.7) | |

| 1999 | 210 | 954,677 | 5.8 (0.6) | |

| 2000 | 317 | 1,356,238 | 8.3 (1.0) | |

| 2001 | 454 | 1,384,499 | 8.5 (0.9) | |

| 2002 | 510 | 1,636,818 | 10.0 (0.5) | |

| 2003 | 574 | 1,589,127 | 9.7 (0.7) | |

| 2004 | 517 | 1,617,857 | 9.9 (0.9) | |

| 2005 | 519 | 1,854,987 | 11.3 (0.9) | |

| 2006 | 574 | 2,043,929 | 12.5 (1.0) | |

| 2007 | 570 | 1,931,227 | 11.8 (1.0) | |

| TOTAL | 4,726 | 16,379,580 | 100 |

Adjusted for survey design

Figure 1.

Venn diagram of Medication including Analgesic and Antibiotics Received for NTDC visits at the ED, 1997–2007. The percentages represent the survey-weighted proportions for the different medications prescribed for NTDC visits. The percentages add up to 100%.

Figure 2.

Percentages of Different Medications Prescribed for NTDC Visits by Age, Payer Type, Race/ethnicity and Calendar Year

Abx – antibiotic; Ag – analgesic, A/A – antibiotic or analgesic; Any – any medication.

*** - <0.001, ** - <0.01, * - <0.05.

In the bivariate analysis, self-pay patients (89% medication, 79% analgesic, 62% antibiotic) and Medicaid enrollees (87% medication, 73% analgesic, 57% antibiotic) had a significantly higher probability of receiving prescriptions for medications, analgesics and antibiotics at an NTDC visit (p<0.0001). Non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics had a higher percentage of antibiotic and analgesic prescriptions than other racial/ethnic groups at 58% and 53% respectively. There was a significant difference by gender for medications prescribed at the ED for NTDC visits.

Findings for the multivariable logistic regression are shown in the Table 2. The overall probability of receiving antibiotics and analgesics in emergency departments for NTDC visits steadily increased over time: OR=1.06 (p<0.0001) and OR =1.11 (p=0.0001) per year. Compared to private insurance patients, self-pay patients had significantly higher adjusted odds of receiving a prescription for antibiotics at NTDC visits to the ED. Compared to patients aged 19–33 years old, patients between the ages of 0–4 years had significantly lower odds of receiving antibiotics for an NTDC visit to the ED, and those under 18 years and above 53 years old as well as adults 73 years and older were less likely to receive a prescription for analgesics. White subjects had significantly higher odds of receiving any medication for NTDC visits at the ED, compared to non-Hispanic Blacks. Interestingly, no racial/ethnic differences were found in the probability of receiving antibiotics or analgesics. In terms of reason for visits, subject with non-dental reason for visit had significantly lower odds of receiving antibiotics and analgesics when compared to those with a dental reason for visit.

Table 2.

Multivariable Analysis of Factors Associated with Receiving Any Medication, Antibiotic and Analgesic with Nontraumatic Dental Condition Visits to Emergency Departments

| Predictor | Any medication | Antibiotic | Analgesic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Calendar Year | 1.10 (1.06–1.14) | <.0001 | 1.06 (1.04–1.09) | <.0001 | 1.11 (1.07–1.14) | <.0001 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 00–04 | 0.63 (0.40–0.98) | 0.0409 | 0.48 (0.32–0.71) | 0.0003 | 0.57 (0.39–0.84) | 0.0043 |

| 05–18 | 0.81 (0.52–1.26) | 0.3483 | 0.77 (0.57–1.04) | 0.0827 | 0.68 (0.49–0.94) | 0.0213 |

| 19–33 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 34–52 | 1.02 (0.78–1.34) | 0.8701 | 1.11 (0.94–1.32) | 0.2317 | 0.95 (0.75–1.20) | 0.6748 |

| 53–72 | 0.61 (0.39–0.96) | 0.0327 | 0.78 (0.55–1.09) | 0.1467 | 0.46 (0.29–0.71) | 0.0006 |

| 73 and older | 0.49 (0.22–1.10) | 0.0840 | 0.75 (0.39–1.45) | 0.3937 | 0.28 (0.13–0.62) | 0.0015 |

| *Insurance | ||||||

| Private insurance | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Medicaid | 0.99 (0.71–1.37) | 0.9450 | 1.22 (0.99–1.51) | 0.0663 | 0.94 (0.74–1.19) | 0.5849 |

| Medicare | 0.74 (0.44–1.26) | 0.2718 | 0.84 (0.58–1.20) | 0.3340 | 1.07 (0.68–1.68) | 0.7842 |

| Self-pay | 1.10 (0.80–1.50) | 0.5461 | 1.38 (1.12–1.71) | 0.0027 | 1.19 (0.93–1.53) | 0.1634 |

| Other | 0.96 (0.47–1.94) | 0.9003 | 1.04 (0.69–1.59) | 0.8418 | 1.09 (0.64–1.87) | 0.7512 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Female | 1.04 (0.82–1.32) | 0.7475 | 0.98 (0.84–1.15) | 0.8373 | 1.06 (0.89–1.27) | 0.4886 |

| *Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Hispanic | 0.92 (0.64–1.31) | 0.6325 | 0.86 (0.65–1.13) | 0.2699 | 1.08 (0.80–1.45) | 0.6312 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.71 (0.54–0.94) | 0.0149 | 0.90 (0.74–1.09) | 0.2814 | 0.93 (0.76–1.13) | 0.4591 |

| Other | 0.74 (0.35–1.58) | 0.4439 | 0.73 (0.44–1.23) | 0.2400 | 0.90 (0.51–1.59) | 0.7255 |

| Reason for visit | ||||||

| Non-dental | 0.57 (0.45–0.73) | <.0001 | 0.70 (0.58–0.84) | 0.0002 | 0.41 (0.33–0.50) | <.0001 |

| Dental | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

Unknown payer type and ethnicity were incorporated using multiple imputations (payer type 7.1% and/or ethnicity 10.3%), OR=Odds Ratio adjusted for all the other covariates in the table.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates an increase in the prescription of analgesics and antibiotics for NTDC visits to EDs during an 11-year period. From 1997 to 2007 the proportion of patients receiving antibiotics and analgesics increased by 41% and 26%, respectively. Patients who made NTDC visits received at least one analgesic and antibiotic prescription in almost 75% and 54% of the cases, respectively. These findings may suggest a lack of time and uncertainty of diagnosis on the part of the ED physicians.10 In addition, ED physicians may have limited training and understanding of the pathological process involved in pulpal, periodontal, and periapical diseases.10 These increases in the prescription of medication at EDs for NTDC visits are of concern because such prescriptions only provide temporary care for NTDCs.

We identified that analgesics were the most commonly prescribed drugs in EDs for NTDC visits. This finding is consistent with prior studies that have reported that pain/toothache is the most common presenting symptom for patients who make NTDC visits to EDs in both the United States13–15 and the United Kingdom16. While our study did not specifically identify the different types of analgesics (opioids versus non-opioids) prescribed to patients at EDs for NTDC visits, anecdotal reports suggest that most patients who present to the ED with NTDCs receive a prescription for opioids. We also found that patients aged 53–72 years and those 73 years and older had significantly lower odds of receiving a prescription for analgesics. This finding could be related to reports that ED physicians are reluctant to prescribe pain medication to older adults because they generally lack access to the medical records17 of such patients, who may be on multiple medications. Furthermore, it is important to note the relative expense of treating toothache at EDs rather than at dental offices. One study based on data from a large Ohio teaching hospital reported that on the average, it costs at least 4 times more to treat a patient at the ED for pain than at a dental office.14

Despite documented evidence of racial/ethnic disparities in the prescription of analgesics at EDs for fracture treatment,18,19 cancer pain,20 and non-traumatic conditions such as migraine,21 we did not find significant racial/ethnic disparities in the prescription of analgesics in EDs for NTDC visits. This finding was quite interesting, given that pain/toothache is probably the most common symptom that leads to ED visits for NTDCs among people of different races/ethnicities in the United States. However, this lack of racial/ethnic disparity may be related to the lack of specificity in the analyses regarding whether patients received opioids versus non-opioids for NTDC visits in EDs. In addition, prior studies have demonstrated racial/ethnic disparities in the prescription of opioids and have suggested potential reasons for the disparities.21–24

Medical and dental insurance is a primary indicator of access to health care services in the United States.25, 26 Persons without adequate dental coverage do not receive the care needed at the appropriate time and often these persons end up in emergency departments for care. Compared to private insurance patients, we identified that self-pay patients had significantly higher adjusted odds of receiving a prescription for antibiotics. Although not significant, Medicaid enrollees had lower odds of receiving prescriptions for analgesics and antibiotics for NTDCs in EDs, despite prior studies that have documented them as having a disproportionately higher burden of dental disease.27

Our study has several limitations. In the first place, classification of race/ethnicity was determined by hospital interviewers based on their perceptions. Secondly, we are unable to determine whether a patient had multiple visits since the database collected information on visits only. Third, the database only contained information on what was prescribed by the physician, and was not validated by information about whether patients actually filled their prescriptions and consumed the medication. Fourth, the “other and unspecified” groups of the ICD-9-CM codes included in our analysis may contain some traumatic dental conditions. In terms of practice and policy implications, this study demonstrates that patients who present to EDs for NTDC visits receive temporary care by way of analgesics and antibiotics. The prescription of analgesics and antibiotics has associated healthcare cost implications as well as the potential for development of antibiotic resistance/intolerance and abuse. Provision of definitive care for NTDC visits to EDs can be achieved by improved access to dental care through an expanded and or increase dental workforce capacity. Improved management of patients who make NTDC visits to EDs could be achieved by training ED physicians on appropriate treatment modalities based on the recommendation of professional organizations such as the American College of Emergency Physicians.

In conclusion, this study documents a substantial increase in the rates of prescription of analgesics and antibiotics for NTDC visits to EDs over time. Analgesics were prescribed in 3 out of every 4 NTDC visits, while antibiotics were prescribed in 1 out of every 2 NDTC visits to EDs in the United States. Self-pay patients had significantly higher adjusted odds of receiving antibiotics at NDTC visits to EDs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Health grant# 1R15DE021196-01.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Campbell C. Emergency medical treatment and active labor act (EMTALA) JLNC. 2005;16:31–34. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballard DW, Derlet RW, Rich BA, Lowe RA. EMTALA, two decades later: a descriptive review of fiscal year 2000 violations. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;4:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Billings J, Parikh N, Mijanovich T. Emergency department use in New York City: a substitute for primary care? Issue Brief (Common Fund) 2000;33:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halfon N, Newacheck PW, Wood DL, St Peter RF. Routine emergency department use for sick care by children in the United States. Pediatrics. 1996;98:28–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okunseri C, Pajewski N, Brousseau D, Tomany-Korman S, Snyder A, Flores G. Racial and ethnic disparities in nontraumatic dental-condition visits to emergency departments and physician offices. A study of the Wisconsin Medicaid program. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1657–1666. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quinonez C, Gibson D, Jokovic A, Locker D. Emergency department visits for dental care of nontraumatic origin. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37:366–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2009.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis C, Lynch H, Johnston B. Dental Complaints in Emergency Departments: a national perspective. Ann. Emerg Med. 2003;42:93–99. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olson AK, MacEdington E, Kulid JC, Weller RN. Update on antibiotics for endodontic practice. Compend Continuing Educ Dent. 1995;11:328–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pogrel MA. Antibiotics in general practice. Dent Update. 1994;21:274–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mata E, Koren LZ, Morse DR, Sinai IH. Prophrylactic use of penicillin V in teeth with necrotic pulps and asymptomatic periapical radiolucencies. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985;60:201–207. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(85)90294-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dailey YM, Martin MV. Are antibiotics being used appropriately for emergency dental treatment? Brit Dent J. 2001;191:391–393. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dodd MD, Graham CA. Unintentional overdose of analgesia secondary to acute dental pain. Brit Dent J. 2002;193:211–212. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma M, Lindsell C, Jauch E, Panciolo AM. Effect of education and guidelines for treatment of uncomplicated dental pain on patient and provider behavior. Annal of Emerg Med. 2004;44:323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohio Coalition for Oral Health. Dental care of chaos: the real cost of eliminating adult Medicaid dental services [Ohio Primary Care Association website] Available at: http://www.ohiopca.org/OCOH/Medicaid%Ederly%20Fact20Sheet.

- 15.Sonis ST, Valachovic RW. An analysis of dental services based in the emergency room. Spec Care Dentist. 1988;8:106–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1988.tb00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pennycook A, Makower R, Brewer A, Moulton C, Crawford R. The management of dental problems presenting to an accident and emergency department. J R Soc Med. 1993;86:702–703. doi: 10.1177/014107689308601210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rupp T, Delaney KA. Inadequate analgesia in emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2004 Apr;43(4):494–503. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.11.019. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Todd KH, Samaroo N, Hoffman JR. Ethnicity as a risk factor for inadequate emergency department analgesia. JAMA. 1993;269:1537–1539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Todd KH, Deaton C, D’Adamo AP, et al. Ethnicity and analgesic practice. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:11–16. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(00)70099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernabei R, Gambassi G, Lapane K, et al. Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. SAGE study Group. Systematic Assessment of Geriatric Drug Use via Epidemiology. JAMA. 1998;279:1877–1882. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.23.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamayo-Sarver JH, Hinze SW, Cydulka RK, Baker DW. Racial and ethnic disparities in emergency department analgesic prescription. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:2067–2073. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.12.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sleath B, Roter D, Chewning B, Svarstad B. Asking questions about medication: analysis of physician-patient interactions and physician perceptions. Med Care. 1999;37:1169–1173. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199911000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LaVeist TA, Nickerson KJ, Bowie JV. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(Suppl 1):146–161. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamayo-Sarver JH, Dawson NV, Cydulka RK, Wigton RS, Baker DW. Variability in emergency physician decision making about prescribing opioid analgesics. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:483–493. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bloom B, Cohen RA. Dental insurance for persons under age 65 years with private health insurance: United States, 2008. NCHS data brief, no 40. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lasser KE, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Access to care, health status, and health disparities in the United States and Canada: results of a cross-national population-based survey. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1300–1307. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.059402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National healthcare disparities report, 2003. Rockville, Md.: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services publication 04-0035; [Google Scholar]