Abstract

The ClpXP proteolytic complex is critical for maintaining cellular homeostasis, as well as expression of virulence properties. However, with the exception of the Spx global regulator, the molecular mechanisms by which the ClpXP complex exerts its influence in Streptococcus mutans are not well understood. Here, microarray analysis was used to provide novel insights into the scope of ClpXP proteolysis in S. mutans. In a ΔclpP strain, 288 genes showed significant changes in relative transcript amounts (P≤0.001, twofold cut-off) as compared with the parent. Similarly, 242 genes were differentially expressed by a ΔclpX strain, 113 (47 %) of which also appeared in the ΔclpP microarrays. Several genes associated with cell growth were downregulated in both mutants, consistent with the slow-growth phenotype of the Δclp strains. Among the upregulated genes were those encoding enzymes required for the biosynthesis of intracellular polysaccharides (glg genes) and malolactic fermentation (mle genes). Enhanced expression of glg and mle genes in ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains correlated with increased storage of intracellular polysaccharide and enhanced malolactic fermentation activity, respectively. Expression of several genes known or predicted to be involved in competence and mutacin production was downregulated in the Δclp strains. Follow-up transformation efficiency and deferred antagonism assays validated the microarray data by showing that competence and mutacin production were dramatically impaired in the Δclp strains. Collectively, our results reveal the broad scope of ClpXP regulation in S. mutans homeostasis and identify several virulence-related traits that are influenced by ClpXP proteolysis.

Introduction

Streptococcus mutans is a member of the oral microbiome known for its close association with dental caries and, occasionally, infective endocarditis. The niche in which S. mutans thrives is the biofilm that forms on the enamel surface of teeth (Loesche, 1986). The dental biofilm environment is constantly and unpredictably changing due to the eating habits of the human host, resulting in large fluctuations in nutrient source and availability, pH, and oxygen tension, among other stresses (Lemos & Burne, 2008). The remarkable ability of S. mutans to tolerate and thrive during stressful conditions, particularly low pH, is closely linked to its virulence in the oral cavity.

The Clp proteolytic complex is critical in maintaining cellular homeostasis, particularly for organisms that must continually endure environmental fluctuations (Frees et al., 2004; Gottesman, 2003; Jenal & Hengge-Aronis, 2003; Kajfasz et al., 2009). In S. mutans, Clp proteases are the result of the association of the ClpP peptidase with one of several Clp ATPases (ClpC, ClpE or ClpX), forming barrel-shaped complexes that will target proteins for degradation (Kajfasz et al., 2009; Lemos & Burne, 2002). Although S. mutans also encodes ClpB and ClpL ATPases, these proteins do not contain the recognition tripeptide that permits interaction with ClpP, and are believed to function mainly as molecular chaperones (Frees et al., 2004; Kajfasz et al., 2009). When Clp ATPase subunits associate with ClpP, the resulting protease performs an important protein quality control role by targeting damaged or misfolded proteins, threading them through its barrel for degradation (Butler et al., 2006; Jenal & Hengge-Aronis, 2003). This process is particularly important during stressful conditions that increase the likelihood of misfolded or damaged cellular proteins. Notably, Clp proteases also target regulatory proteins, thereby keeping their numbers in check, and providing a link between Clp proteolysis and regulation of gene expression (Frees et al., 2004; Zuber, 2004).

Previously, we and others have demonstrated that ClpP plays an important role in the expression of key virulence attributes of S. mutans, including biofilm formation, cell viability and acid tolerance (Chattoraj et al., 2010; Deng et al., 2007; Kajfasz et al., 2009; Lemos & Burne, 2002; Zhang et al., 2009). We also uncovered some surprising phenotypic characteristics shared by strains bearing deletions in clpP or clpX, including enhanced survival under short- and long-term acidic conditions and increased sucrose-dependent biofilm formation (Kajfasz et al., 2009). Additionally, we showed that the Spx global regulator accumulates in S. mutans strains lacking functional ClpXP proteolysis and that inactivation of either one of the two Spx orthologues, SpxA and SpxB, caused a reversion of many phenotypes observed in S. mutans ΔclpX and ΔclpP strains (Kajfasz et al., 2009). Thus, the underlying mechanisms by which ClpXP affects virulence traits in S. mutans are intimately associated with accumulation of the SpxA and SpxB proteins. However, not all phenotypes associated with the clpP or clpX mutant strains are expected to be linked to Spx accumulation, as several distinct biological traits and regulatory circuits controlled by Clp proteolysis in other bacterial species are known to be Spx-independent (Frees et al., 2007).

Although ClpP proteolysis has been consistently implicated in virulence (Frees et al., 2003; Gaillot et al., 2000; Ibrahim et al., 2005), has shown promising results as a vaccine candidate (Kwon et al., 2004) and is the target of two new classes of antibiotics (Böttcher & Sieber, 2008; Brötz-Oesterhelt et al., 2005), a complete picture of the biological role of Clp-dependent proteolysis in bacterial pathogenesis has yet to emerge. As our previous study established a firm connection between ClpXP proteolysis and cellular accumulation of Spx proteins, our goals in this study were to unveil the scope of the ClpXP regulon and to identify and characterize virulence traits linked to functional ClpXP proteolysis in both Spx-dependent and Spx-independent manners. Microarray analysis provided insights into the pleiotropic effects of deletions of clpP and clpX in S. mutans, with expression of more than 10 % of the genome altered in each case. A follow-up physiological characterization of selected virulence traits of S. mutans identified in the microarrays validated the transcriptomic data and revealed that ClpXP proteolysis is involved in intracellular polysaccharide (IPS) production, malolactic fermentation (MLF), competence development and bacteriocin production.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. S. mutans UA159 and its derivatives were routinely grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 atmosphere. When appropriate, kanamycin (Kan, 1 mg ml−1) or erythromycin (Erm, 10 µg ml−1) was added to the growth medium. For microarray analysis, S. mutans UA159 (wild-type) and its Δclp derivatives were grown in BHI medium to mid-exponential phase (OD600 0.5).

Table 1. Strains used in this study.

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Source or reference |

| S. mutans | ||

| UA159 | Wild-type | Laboratory stock |

| JL1 (ΔclpP) | clpP : : NP (non-polar) Kan | Kajfasz et al. (2009) |

| JL2 (ΔclpX) | clpX : : NPKan | Kajfasz et al. (2009) |

| JL29 | UA159+pMSP3535 | This study |

| JL30 (ΔclpP complement) | JL1+pMSP3535 expressing clpP | This study |

| JL31 (ΔclpX complement) | JL2+pMSP3535 expressing clpX | This study |

| JL26 (Δglg region) | glgB glgC glgD : : Erm | This study |

| JL27 (ΔclpP/Δglg region) | clpP : : NPKan; glg : : Erm | This study |

| JL28 (ΔclpX/Δglg region) | clpX : : NPKan; glg : : Erm | This study |

| Other species | ||

| L. lactis ATCC 11454 | Wild-type | Laboratory stock |

| S. gordonii DL-1 | Wild-type | Laboratory stock |

RNA extraction.

RNA from S. mutans cells was isolated as described previously (Abranches et al., 2006). Briefly, S. mutans cells grown to the desired OD600 were homogenized by repeated hot acid phenol/chloroform extractions. The nucleic acid was precipitated with 1 vol. cold 2-propanol and 0.1 vol. 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5) at −20 °C overnight. RNA pellets were resuspended in nuclease-free H2O and treated with DNase I (Ambion) at 37 °C for 30 min. The RNA was repurified using an RNeasy mini-kit (Qiagen), including a second on-column DNase treatment as recommended by the supplier. RNA concentrations were determined in triplicate and samples were run on an agarose gel to verify RNA integrity.

Microarray experiments.

S. mutans UA159 version 1 microarray slides were provided by the J. Craig Venter Institute Pathogen Functional Genomics Resource Center (PFGRC; http://pfgrc.jcvi.org/index.php/microarray). The microarray experiments and analysis were as previously described (Abranches et al., 2006; Kajfasz et al., 2010). Briefly, reference RNA was prepared from S. mutans UA159 cells that were grown in BHI medium to an OD600 of 0.5, and used in all hybridizations. cDNA samples generated from 2 µg RNA originating from four independent cultures of each strain studied were hybridized to the microarray slides, as was cDNA derived from the reference culture. cDNA was coupled to Cy3-dUTP (test samples) or Cy5-dUTP (reference samples; GE Healthcare). Mixtures of test and reference cDNA were hybridized to the microarray slides for 16 h at 42 °C in a MAUI (MicroArray User Interface) hybridization chamber (BioMicro Systems). Hybridized slides were washed and scanned using a GenePix scanner (Axon Instruments). Data were analysed using the T4 software suite available at the PFGRC website. Statistical analysis was carried out with BRB Array Tools (http://linus.nci.nih.gov/BRB-ArrayTools.html) with a cut-off P-value of 0.001. Additional details regarding array protocols are available at http://pfgrc.jcvi.org/index.php/microarray/protocols.html. Microarray data have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under GEO Series accession number GSE29871.

Real-time quantitative PCR.

A subset of genes was selected to validate the microarray data by real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR). Gene-specific primers (see Supplementary Table S1, available with the online version of this paper) were designed using Beacon Designer, version 2.0, software (Premier Biosoft International). Reverse transcription and qRT-PCR were carried out according to previously described protocols (Abranches et al., 2006; Lemos et al., 2008). A Student’s t-test was performed to verify significance of the PCR quantifications.

Construction of glg mutant strains.

Standard DNA manipulation techniques were used as previously described (Lemos & Burne, 2002; Sambrook et al., 1989). The primers used to isolate the mutants are listed in Supplementary Table S1. S. mutans strains lacking an approximately 2.4 kb region of the genome encompassing 1160 bases of the 3′ end of glgB, all 1146 bases of glgC and 100 bases of the 5′ end of glgD were constructed using a PCR ligation mutagenesis approach (Lau et al., 2002). Briefly, PCR fragments flanking the 5′ end of glgB and the 3′ end of glgD were obtained and ligated to an erythromycin resistance (Ermr) marker, and the ligation mix was used to transform S. mutans UA159. Mutant strains were isolated on BHI plates supplemented with Erm. Double ΔclpP (or ΔclpX) Δglg strains were constructed by transformation of the single Δclp strains with the glg deletion PCR fragment obtained from the Δglg strain. The deletions were confirmed as correct by PCR sequencing of the insertion site and flanking sequences.

IPS determination.

Accumulation of stored IPS was evaluated by using a colorimetric assay that relies on the formation of an iodine–polysaccharide complex (Busuioc et al., 2009). Briefly, bacteria were streaked on Todd–Hewitt agar plates containing 2 % glucose or 2 % sucrose and incubated for 48 h. The plates were then flooded with 5 ml iodine solution [0.2 % (w/v) iodine in 2.0 % (w/v) potassium iodide solution]. IPS was detected by the formation of a brown pigment, which was visible almost immediately upon adding the iodine solution.

Glycolytic pH minima.

The ability of S. mutans strains to continue to undergo glycolysis in an increasingly acidic environment was evaluated by pH drop experiments (Belli & Marquis, 1991). Cultures of S. mutans strains grown to exponential phase were harvested by centrifugation, washed in ice-cold distilled water and resuspended in 10 % culture volume of 50 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2 salt solution. KOH was used to titrate the suspensions to pH 7.2. Glycolysis was initiated with the addition of 55.6 mM glucose, and the resulting fall in pH of the suspension was monitored over a 30 min period. To study differences in sugar storage, changes in pH were also monitored immediately after cells were resuspended in salt solution, without addition of glucose.

Long-term survival.

The ability of the S. mutans Δglg strains to survive a period of several days at low pH was assessed via long-term survival assays, in which an overnight culture of cells was diluted 1 : 20 in tryptone-yeast extract (TY) medium containing excess glucose (50 mM) (Kajfasz et al., 2009, 2010). The growth and pH of the cultures were monitored at 37 °C and 5 % CO2 until stationary phase was reached, at which point an aliquot was removed for serial dilution and plating on BHI agar. Bacterial survival was assessed by plating the cultures daily until growth was no longer detected.

Malolactic fermentation assay.

The MLF assay was performed as previously described (Martinez et al., 2010; Sheng & Marquis, 2007). Briefly, overnight cultures were grown in BHI medium buffered to pH 7 with 25 mM KPO4, then cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed with 50 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2 salt solution, and starved for 1 h at 37 °C in half the original culture volume of salt solution. After the starvation period, cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in half the culture volume of potassium phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7). To assay for MLF activity, the suspension was adjusted to pH 4.0 with HCl to achieve the optimal pH for MLF activity in S. mutans (Sheng & Marquis, 2007), and MLF was initiated by the addition of l-malic acid to a final concentration of 50 mM. Aliquots were removed immediately and 90 min following the addition of l-malic acid, and assayed for the presence of l-malate in the supernatant by using a l-malic acid detection kit (R-Biopharm). The values of l-malic acid metabolized were normalized to cell dry weight of the samples.

Assay of genetic competence.

Cultures were diluted 1 : 20 in 500 µl BHI medium containing 10 % horse serum, and grown to an OD600 of 0.15 at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 atmosphere, at which point 200 ng plasmid pMSP3535 (Bryan et al., 2000) was added. When desired, 5 µl (at 1 mg ml–1) of synthetic competence-stimulating peptide (CSP) (Li et al., 2001) was added to the cultures. The cultures were incubated until stationary phase was reached (≈3 h for UA159, ≈4.5 h for ΔclpX and ≈5 h for ΔclpP). Transformants and total c.f.u. were enumerated by plating appropriate dilutions on BHI agar plates with and without Erm, respectively. The numbers of c.f.u. were counted after 72 h of incubation, and transformation efficiency was expressed as the percentage of transformants among the total viable cells.

Deferred antagonism assay.

Bacteriocin production was measured by assaying the ability of S. mutans to inhibit the growth of mutacin IV- and mutacin V-sensitive species, Streptococcus gordonii and Lactococcus lactis, respectively. Briefly, S. mutans cultures grown to an OD600 of 0.3 were spotted onto BHI agar and incubated for 24 h. Following incubation, 500 µl of an overnight culture of S. gordonii or L. lactis was added to 5 ml soft (0.75 %) BHI agar, spread as an overlay and incubated for another 24 h before zones of growth inhibition around the S. mutans spots were measured.

Results

Microarray analysis provides novel insights into the scope of ClpXP proteolysis in S. mutans

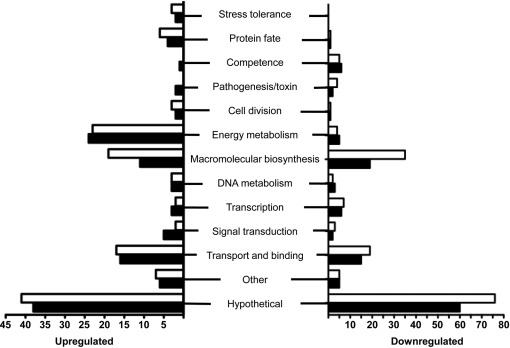

To gain a better understanding of the phenotypes previously observed in the ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains (Kajfasz et al., 2009; Lemos & Burne, 2002), microarray analysis was performed to compare the transcriptome of mid-exponential-phase cultures of each mutant with that of the parent strain. Prior to the microarray analysis, both ΔclpP and ΔclpX were complemented by providing, respectively, the full-length clpP and clpX genes in trans using the nisin-inducible plasmid pMSP3535 (Bryan et al., 2000). Several phenotypes characteristic of the ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains (Kajfasz et al., 2009), including slow growth rates and aggregation in broth, were fully reversed by the complementation (Supplementary Figs S1, S2 and S3). At an assigned P-value of ≤0.001 and applying a twofold change cut-off, there were 288 genes in the ΔclpP strain and 242 in ΔclpX that showed significant changes in relative transcript amounts as compared with the parent strain. The complete list of genes with altered expression in the Δclp strains is provided in Supplementary Table S2. Of the 242 genes differentially expressed in ΔclpX, 113 (47 %) also appeared, following the same trend, in the ΔclpP microarrays. The genes found to be differentially expressed in only one of the two mutant strains are probably due to a ClpP-independent function of ClpX, or to ClpP interactions with another Clp ATPase partner (ClpC or ClpE). To facilitate data interpretation, the genes that appeared on these microarray analyses were grouped into functional categories (Fig. 1). A subset of the differentially expressed genes was selected and used for qRT-PCR analysis (Supplementary Table S1) for validation of the microarray data, and the results were consistent with the expression trends observed in the microarrays.

Fig. 1.

Numbers of genes separated by functional categories that were differentially expressed by S. mutans ΔclpP (open bars) and ΔclpX (solid bars) as compared with the parent strain UA159 with a twofold cut-off (P≤0.001).

Several genes encoding ribosomal proteins, translation initiation factors and elongation factors were downregulated in both mutants, consistent with the slow-growth phenotype previously described for the two Δclp mutant strains (Kajfasz et al., 2009). Interestingly, an overall upregulation of genes involved in energy metabolism (acoB, adh, mle, pckA, pfl, among others) and in sugar uptake and metabolism (glg, gtfB, mal, msm and scr) was observed in the mutants, suggesting an increased need for ATP by these strains. Genes encoding putative peptidases or endopeptidases (gcp, pepO, pepB, pepT) were found to be upregulated in both ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains, a finding that suggests an attempt by the cells to compensate for the loss of ClpXP ‘housekeeping’ proteolysis.

Previous studies showed an increased capacity of the ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains to form biofilms when grown with sucrose (Deng et al., 2007; Kajfasz et al., 2009), suggesting that glucan production is enhanced in these strains. Our microarrays showed that expression of gtfB, encoding the glucosyltransferase B enzyme responsible for establishing the extracellular polysaccharide matrix along with gtfC and gtfD (Ooshima et al., 2001), was upregulated more than fourfold in ΔclpP, and more than sixfold in ΔclpX. Western blot analysis using a polyclonal antibody against the S. mutans GtfB protein (Wunder & Bowen, 2000) confirmed that expression of GtfB was higher in ΔclpP and ΔclpX (data not shown).

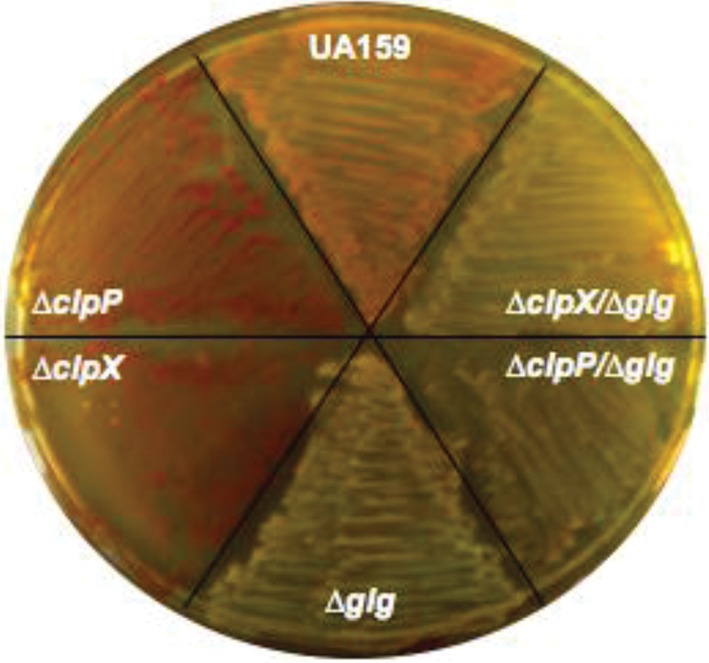

The ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains exhibit enhanced accumulation of IPS

A common trend revealed by the microarray data was the enhanced expression of the glg genes, coding for the enzymes responsible for the production of glycogen-like IPS. To investigate whether the ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains have enhanced capacity to store IPS, we used an iodine-staining colorimetric assay to visualize IPS accumulation. Both ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains indeed showed enhanced accumulation of IPS, as demonstrated by a darker brown colour compared to the light brown colour observed in the parent strain (Fig. 2). To investigate whether these phenotypes in the Δclp strains would revert when the glg operon was disrupted, we created double mutants by inserting the glg mutation (constructed by deleting a 2.4 kb region encoding all of glgC, as well as parts of glgB and glgD) in the ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains. As expected, the Δglg, ΔclpP/Δglg and ΔclpX/Δglg strains showed no apparent incorporation of the iodine solution (Fig. 2). Similar results were observed with plates containing 2 % sucrose (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Vizualization of IPS stores in S. mutans UA159 and its derivatives. Agar plates inoculated with S. mutans UA159, ΔclpP, ΔclpX, Δglg, ΔclpP/Δglg and ΔclpX/Δglg were flooded with iodine solution. IPS was visualized by the formation of a brown pigment. The image shown is a representative of three independent experiments.

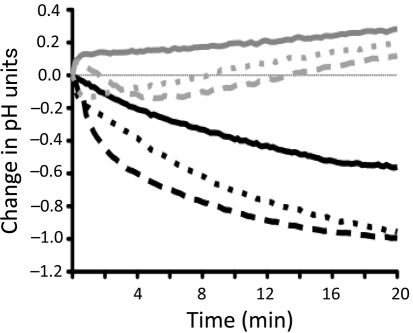

To further demonstrate that the clpP and clpX mutants have enhanced IPS storage, we performed pH drop experiments to evaluate the ability of these strains to reduce the extracellular pH through glycolysis. When the pH drop experiment was performed by the addition of glucose to cells resuspended in salt solution, no differences in kinetics and final pH were observed between the parent, ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains (data not shown). To evaluate the consumption of endogenous sugars, the pH drop experiments were repeated without pH titration or the addition of exogenous glucose, so that any drop in the extracellular pH could be attributed to IPS utilization. In this case, both the ΔclpP and the ΔclpX strains were able to reduce the pH faster and to values considerably lower than those of the parent strain (over 0.5 pH units lower) (Fig. 3). As expected, the Δglg as well as the Δclp/Δglg double mutants were unable to lower the pH without addition of exogenous glucose.

Fig. 3.

Glycolytic pH minima of S. mutans UA159 (black solid line), ΔclpP (black dashed line), ΔclpX (black dotted line), Δglg (grey solid line), ΔclpP/Δglg (grey dashed line) and ΔclpX/Δglg (grey dotted line). pH drop experiments were performed without addition of glucose to cells. The curves shown are representatives of at least three independent experiments.

Increased production of IPS by the Δclp strains does not appear to account for the enhanced survival phenotype

To test the hypothesis that enhanced IPS storage contributes to the prolonged survival of S. mutans, we repeated the long-term survival assay with the ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains (Kajfasz et al., 2009), including the Δglg and Δclp/Δglg strains that were unable to accumulate IPS. When grown in TY medium containing 50 mM glucose at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 atmosphere, all strains attained a similar final pH of approximately 4.2 within 18–24 h of initiating the experiment. However, we did not see a reversion of the enhanced-survival phenotype when a deletion in the glg operon was added to the Δclp strains (data not shown), suggesting that enhanced IPS storage plays a minor role in the enhanced survival of the ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains.

MLF activity is significantly enhanced in the absence of ClpXP proteolysis

Our microarray analysis also revealed that the genes responsible for MLF, mleS (SMU.0137) and mleP (SMU.0138), were highly upregulated in both ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains (>10-fold induction, Supplementary Table S2). Recently, MLF has been identified as an important buffering system in S. mutans and shown to protect the cells against acid, oxidative and starvation stresses (Lemme et al., 2010; Sheng & Marquis, 2007; Sheng et al., 2010). The mle genes and enzyme activity are positively regulated by addition of external l-malate and by low pH (Lemme et al., 2010; Martinez et al., 2010; Sheng & Marquis, 2007). In agreement with our microarray data, MLF activity was minimal in the wild-type strain grown without addition of l-malate at pH 7 but a >10-fold increase in activity was seen in ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains grown under the same conditions (mean MLF activity reported as µmol l-malate decarboxylated during a 90 min period per mg cell dry weight: S. mutans UA159, 1.196; ΔclpP, 12.64, P≤0.005; ΔclpX, 13.53, P≤0.0005). When cultures were grown in the presence of 25 mM l-malate, the ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains also showed significantly enhanced ability to metabolize l-malic acid at both neutral and acidic (pH 5.5) pH values (data not shown).

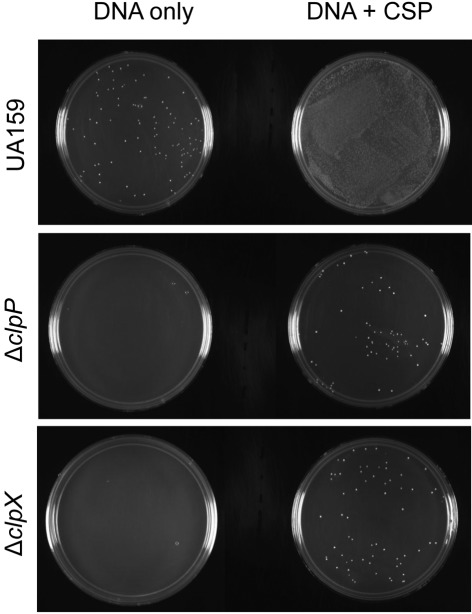

ClpXP proteolysis regulates competence development and bacteriocin production

The microarray data also revealed that transcription of a number of genes known or predicted to be involved in competence development and bacteriocin production were downregulated in the Δclp strains (Table 2). Among the known competence genes found to be downregulated were the sigma factor comX, several genes of the late competence comY operon and the newly described comR transcriptional regulator (Mashburn-Warren et al., 2010). We assessed the transformation efficiency of ΔclpP and ΔclpX with and without the addition of exogenous CSP. In the absence of CSP, we were unable to obtain a single transformant colony of the ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains, whereas UA159 was readily transformable (3.05×10−5 % transformation efficiency). Addition of exogenous CSP re-established competence in ΔclpP and ΔclpX (1.2×10−4 and 2×10−5 % transformation efficiencies, respectively), but dramatically improved transformation efficiencies of the parent strain (8.7×10−3 %). Fig. 4 shows a typical example of the number of transformants obtained for each strain at the same serial dilution.

Table 2. Competence- and bacteriocin-related genes differentially expressed in the ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains.

| Expression relative to UA159 | ||||

| Locus tag | Gene name | Definition | ΔclpP | ΔclpX |

| SMU.0061 | comR | Rgg family, transcriptional regulator | 0.119 | |

| SMU.0150 | nlmA | Non-lantibiotic mutacin IV A | 0.121 | |

| SMU.0151 | nlmB | Non-lantibiotic mutacin IV B, GG-motif-containing peptide | 0.223 | |

| SMU.0259 | oppF | Oligopeptide ABC transporter | 0.246 | |

| SMU.0283 | GG-motif-containing peptide | 0.226 | 0.129 | |

| SMU.0286 | nlmT | ABC transporter, bacteriocin | 0.309 | |

| SMU.0287 | nlmE | ABC transporter, bacteriocin | 0.244 | 0.209 |

| SMU.0423 | bsmC | Putative bacteriocin | 0.142 | 0.327 |

| SMU.0499 | comFC | Late competence gene | 7.392 | |

| SMU.1811 | scnF | ABC transporter, bacteriocin | 0.192 | |

| SMU.1855 | hrdM | Histidine kinase | 0.377 | |

| SMU.1889 | GG-motif-containing peptide | 5.492 | ||

| SMU.1895 | GG-motif-containing peptide | 0.174 | 0.314 | |

| SMU.1896 | GG-motif-containing peptide | 0.133 | 0.284 | |

| SMU.1903 | Hypothetical protein | 0.095 | ||

| SMU.1904 | Hypothetical protein | 0.100 | ||

| SMU.1905 | bsmL | GG-motif-containing peptide | 0.102 | |

| SMU.1906 | bsmB | Putative bacteriocin, GG-motif-containing peptide | 0.168 | |

| SMU.1908 | Hypothetical protein | 0.047 | ||

| SMU.1909 | Hypothetical protein | 0.054 | ||

| SMU.1910 | Hypothetical protein | 0.027 | ||

| SMU.1912 | Hypothetical protein | 0.078 | ||

| SMU.1913 | blpL | Putative immunity protein | 0.068 | |

| SMU.1914 | cipB, nlmC | Mutacin V, GG-motif-containing peptide | 0.183 | |

| SMU.1916 | comD | Histidine kinase | 0.286 | 0.346 |

| SMU.1981 | comG | Late competence gene | 0.216 | |

| SMU.1982 | Hypothetical protein | 0.096 | ||

| SMU.1984 | comYC | Late competence gene | 0.354 | |

| SMU.1985 | comYB | Late competence gene | 0.354 | 0.094 |

| SMU.1987 | comYA | Late competence gene | 0.220 | |

| SMU.1997 | comX | Sigma factor ComX | 0.227 | |

Fig. 4.

Genetic competence of S. mutans UA159, ΔclpP and ΔclpX. Plasmid (pMSP3535) was added to early exponential-phase (OD600 of 0.15) cells with or without the addition of CSP, then plated at stationary phase. Images shown are representatives of three independent experiments.

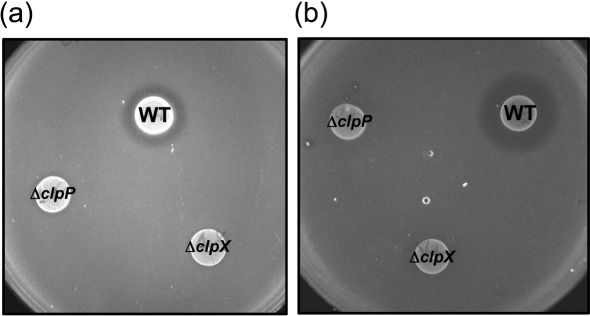

Among the bacteriocin-related genes that appeared in the microarray analysis were nlmA and nlmB, encoding the non-lantibiotic mutacin IV (Qi et al., 2001), and cipB (nlmC), encoding mutacin V (Hale et al., 2005; Matsumoto-Nakano & Kuramitsu, 2006). We performed a deferred antagonism assay, which revealed that the ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains have lost the ability to antagonize growth of S. gordonii or L. lactis by producing, respectively, mutacin IV or mutacin V (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Deferred antagonism assay. S. mutans UA159 (wild-type, WT), ΔclpP and ΔclpX were spotted onto agar plates and allowed to grow for 24 h before an overlay with the test strain was introduced. (a) Overlay with S. gordonii DL-1 (mutacin IV sensitive). (b) Overlay with L. lactis ATCC 11454 (mutacin V sensitive). The images shown are representatives of three independent experiments.

Discussion

In the oral cavity, S. mutans must cope with large and constant environmental fluctuations, including changes in pH, oxygen tension, and nutrient source and availability (Lemos & Burne, 2008). In such an environment, cytoplasmic proteases that control the stability of regulatory proteins and prevent the accumulation of damaged proteins are central to physiological homeostasis and virulence. Clp-dependent proteolysis is of particular relevance in Streptococcus, as this genus lacks other known cytoplasmic proteases, such as Lon and ClpYQ (Kajfasz et al., 2009). In fact, proteolysis mediated through ClpXP is an important trait for stress tolerance, gene regulation and virulence in several Gram-positive pathogens (Chastanet et al., 2001; Chattoraj et al., 2010; Frees et al., 2003, 2004; Gaillot et al., 2000; Ibrahim et al., 2005; Kwon et al., 2004). Previously, we demonstrated that a number of virulence properties of S. mutans, including stress tolerance, biofilm formation and colonization in a rodent caries model, were influenced by ClpXP proteolysis (Kajfasz et al., 2009). Although we have shown that accumulation of the global regulators SpxA and SpxB was associated with a number of the phenotypes observed in the ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains (Kajfasz et al., 2009), we reasoned that ClpXP would probably control a number of additional physiological properties of S. mutans in an Spx-independent manner.

Here, we used microarrays to better understand the global effects of ClpXP proteolysis in S. mutans. The large number of genes that were differentially expressed as compared with the parent strain supports the hypothesis that ClpXP is critical for S. mutans homeostasis, as the number of differentially expressed genes represents over 12 % of the S. mutans genome (Ajdić et al., 2002). The large number of genes following the same trend in both mutants confirmed the cooperative nature of ClpP and ClpX, and is in agreement with the nearly identical phenotypes previously observed for the ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains (Kajfasz et al., 2009). Surprisingly, the genes found to be differentially expressed in our ΔclpP arrays showed limited overlap with a previous microarray analysis that used an S. mutans clpP mutant generated using a markerless gene deletion system (Chattoraj et al., 2010). Despite differences in growth conditions, microarray platform and mutant construction, the reasons for the small number of genes following the same trend in the current and previous study are not entirely clear.

Some of the trends that were uncovered by the microarray analysis support the relationship that we have previously demonstrated between ClpXP proteolysis and the transcriptional regulators SpxA and SpxB (Kajfasz et al., 2010), which are targets of ClpXP proteolysis. For example, the genes encoding Gor and TrxB, two enzymes involved in oxidative stress responses regulated by Spx, were upregulated in the Δclp strains. These same genes were downregulated in ΔspxA and ΔspxAB microarrays (Kajfasz et al., 2010). Although this relationship between regulatory mechanisms of ClpXP and Spx is clearly important, the analysis described here also identified new genes and pathways that are under ClpXP proteolytic control in an Spx-independent fashion.

Our microarray analysis identified a large number of genes involved in sugar uptake and metabolism as being upregulated in the Δclp strains. Among these were the genes encoding enzymes responsible for the biosynthesis of IPS, a glycogen-like polymer that serves as a storage form of carbohydrate (DiPersio et al., 1978). The synthesis of IPS has been implicated in enhanced survival of S. mutans and has been shown to contribute to caries formation (Gibbons & Socransky, 1962; Spatafora et al., 1995; van Houte et al., 1970). Previous work revealed that production of IPS via glgA (encoding glycogen synthase) significantly extended the survival of S. mutans during starvation, especially when cells were grown in the presence of glucose (Busuioc et al., 2009). The upregulation of several glg genes led us to hypothesize that the enhanced long-term survival of ΔclpP and ΔclpX (Kajfasz et al., 2009) could be associated with increased IPS storage. Although we were able to demonstrate that the ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains indeed accumulate larger amounts of IPS when compared with the parent strain, no phenotypic reversion was seen when the Δclp/Δglg strains were subjected to long-term survival experiments. These results do not rule out that increased IPS stores play a role in the enhanced survival of ΔclpP and ΔclpX but indicate that other factors may participate in the enhanced survival of the Δclp strains. By comparing the transcriptome of the Δclp strains with the previously published Δspx strains (Kajfasz et al., 2010), we found no indication that the upregulation of the glg genes in the ΔclpP microarrays was linked to Spx regulation.

In a previous report, we showed that expression of mleS and mleP (encoding the malolactic enzyme and malate permease, respectively) was downregulated in the ΔspxA/ΔspxB double mutant (Kajfasz et al., 2010). Here, we showed that transcription of mleS and mleP was highly upregulated (>10-fold) in both Δclp strains, suggesting that the enhanced MLF activity of ΔclpP and ΔclpX may be associated with the accumulation of Spx in the absence of ClpXP proteolysis. Work is under way to specifically address the possibility that the mle operon is under Spx transcriptional control.

Although l-malic acid is not an energy source for S. mutans, MLF is a major process for alkali generation and for ATP synthesis by means of F-ATPase acting in the synthase mode (Sheng & Marquis, 2007), a process that confers protection against acid, oxidative and starvation stresses (Lemme et al., 2010; Sheng & Marquis, 2007; Sheng et al., 2010). Thus, it is possible that the enhanced acid tolerance of the Δclp strains in vitro (Kajfasz et al., 2009) may be linked to the increased MLF activity observed in these strains.

Another interesting finding was that a large number of genes involved in competence development and bacteriocin production were downregulated in the Δclp strains. Coordinated competence development and production of bacteriocin have been well documented, suggesting that S. mutans utilizes competence-induced cell lysis to eliminate competition and acquire DNA from neighbouring species (Kreth et al., 2005, 2007; Steinmoen et al., 2003; van der Ploeg, 2005). The repression of competence genes in the S. mutans ΔclpP strain supports previous studies reporting reduced genetic competence of an S. mutans clpP mutant (Lemos & Burne, 2002). We assessed competence in ΔclpP and ΔclpX and found that transformation efficiency of both mutants was drastically reduced. Although only a few competence- and bacteriocin-related genes were differentially expressed in our Δspx microarrays (Kajfasz et al., 2010), studies with Bacillus subtilis and Streptoccocus pneumoniae show a link between Spx regulation and competence development. For example, the B. subtilis Spx negatively regulates competence development by disrupting interactions between the ComA~P response regulator and the C-terminal domain of the RNA polymerase (Nakano et al., 2003). Likewise, the S. pneumoniae SpxA1, a protein sharing 75 % homology with the S. mutans SpxA, was shown to regulate competence in S. pneumoniae by repressing transcription of early competence genes (Turlan et al., 2009). Thus, current evidence points towards a global model in which Spx negatively regulates competence development in Gram-positive bacteria, suggesting that the reduced transformation efficiencies of the S. mutans ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains may be linked to Spx accumulation.

Peptide bacteriocins are produced to inhibit the growth of other microbes sharing the same ecological niche. The S. mutans UA159 strain used in this study produces at least two types of bacteriocins: mutacin IV, encoded by nlmA and nlmB, and mutacin V, encoded by cipB (also known as nlmC). Mutacin IV is active against members of the mitis group of streptococci (Hale et al., 2005; Qi et al., 2001), whereas mutacin V is active mostly against non-streptococcal species (Hale et al., 2005). In addition to the genes encoding mutacin IV and mutacin V, several other bacteriocin-related genes, including immunity factors and the locus encoding the ABC transporter required for mutacin export, nlmET (Hale et al., 2005), were downregulated in both Δclp strains. Deferred antagonism assays confirmed the microarray results and revealed that both ΔclpP and ΔclpX were unable to inhibit growth of mutacin IV- and mutacin V-sensitive strains. Despite the limited overlap of genes found to be differentially expressed in our ΔclpP microarrays and in a previous report (Chattoraj et al., 2010), it is interesting to note that the data regarding expression of bacteriocin-related genes and bacteriocin production between both studies were in full agreement.

A general characteristic of secreted peptides in Gram-positive bacteria is the presence of a highly conserved double glycine (GG) motif preceding the site where specific proteolytic cleavage of the signal peptide occurs during peptide export (Håvarstein et al., 1995). The S. mutans UA159 genome encodes several putative peptides containing the conserved GG motif, including mutacin IV and V, and CSP. Notably, several other putative GG-motif-containing peptides were downregulated in the Δclp strains, suggesting that ClpXP proteolysis may have a broad role in biosynthesis or maturation of secreted peptides. Collectively, these results identify ClpXP proteolysis as a participant in the regulation of competence development and bacteriocin production in S. mutans.

The coordinated activation of competence and bacteriocin production has been linked to S. mutans virulence via different mechanisms that are not mutually exclusive. For example, in addition to killing bacterial competitors, bacteriocin production has been linked to biofilm formation through extracellular DNA release and autolysis (Perry et al., 2009a, b). Perry et al. (2009a) showed that intracellular accumulation of unprocessed CipB (mutacin V) mediates autolysis and proposed that CipB may be involved in altruistic cell death of a subset of the population (fratricide) during stressful conditions. It is tempting to speculate that the unexpected enhanced survival of ΔclpP and ΔclpX during acid stress (Kajfasz et al., 2009) could, at least partially, be explained by a reduction in normal levels of mutacin V-mediated autolysis in these strains. In fact, we have previously shown that the ΔclpP and ΔclpX strains undergo autolysis at a slower rate than the parental strain (Kajfasz et al., 2009). Our previous microarray data with S. mutans Δspx strains did not offer additional insight regarding a direct role of Spx with bacteriocin production. However, given the relationship of Spx regulation with competence in other organisms (Nakano et al., 2003; Turlan et al., 2009), and the tight linkage between competence development and bacteriocin production in S. mutans, we cannot rule out that Spx may participate in the regulation of the genes involved in bacteriocin production in a manner that has yet to be determined.

In summary, the results presented here confirm the broad scope of ClpXP regulation in S. mutans homeostasis and identify virulence-related traits that are influenced by ClpXP proteolysis, including IPS storage, MLF activity and competence/bacteriocin production. Our data further confirm the importance of Spx removal by Clp proteolysis during unstressed conditions, as some of the identified virulence traits affected by ClpXP are probably regulated in an Spx-dependent manner. At the same time, it is clear that ClpXP can also influence the expression of virulence traits, such as IPS storage, in an Spx-independent manner. Considering the high degree of conservation among Clp proteins and given that ClpP-mediated proteolysis is an established virulence factor for several Gram-positive organisms (Frees et al., 2003; Gaillot et al., 2000; Ibrahim et al., 2005; Kajfasz et al., 2009), our findings are likely to have broad implications.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH-NIDCR award DE019783. J. K. K. and J. A. were also supported by the NIDCR training in oral sciences grant T32 DE007202.

Abbreviations:

- CSP

competence-stimulating peptide

- Erm

erythromycin

- IPS

intracellular polysaccharide

- Kan

kanamycin

- MLF

malolactic fermentation

- qRT-PCR

real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

Footnotes

Three supplementary figures and two supplementary tables are available with the online version of this paper.

References

- Abranches J., Candella M. M., Wen Z. T., Baker H. V., Burne R. A. (2006). Different roles of EIIABMan and EIIGlc in regulation of energy metabolism, biofilm development, and competence in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 188, 3748–3756. 10.1128/JB.00169-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajdić D., McShan W. M., McLaughlin R. E., Savić G., Chang J., Carson M. B., Primeaux C., Tian R., Kenton S., et al. & other authors (2002). Genome sequence of Streptococcus mutans UA159, a cariogenic dental pathogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 14434–14439. 10.1073/pnas.172501299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belli W. A., Marquis R. E. (1991). Adaptation of Streptococcus mutans and Enterococcus hirae to acid stress in continuous culture. Appl Environ Microbiol 57, 1134–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böttcher T., Sieber S. A. (2008). Beta-lactones as specific inhibitors of ClpP attenuate the production of extracellular virulence factors of Staphylococcus aureus. J Am Chem Soc 130, 14400–14401. 10.1021/ja8051365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brötz-Oesterhelt H., Beyer D., Kroll H. P., Endermann R., Ladel C., Schroeder W., Hinzen B., Raddatz S., Paulsen H., et al. & other authors (2005). Dysregulation of bacterial proteolytic machinery by a new class of antibiotics. Nat Med 11, 1082–1087. 10.1038/nm1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan E. M., Bae T., Kleerebezem M., Dunny G. M. (2000). Improved vectors for nisin-controlled expression in gram-positive bacteria. Plasmid 44, 183–190. 10.1006/plas.2000.1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busuioc M., Mackiewicz K., Buttaro B. A., Piggot P. J. (2009). Role of intracellular polysaccharide in persistence of Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 191, 7315–7322. 10.1128/JB.00425-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler S. M., Festa R. A., Pearce M. J., Darwin K. H. (2006). Self-compartmentalized bacterial proteases and pathogenesis. Mol Microbiol 60, 553–562. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05128.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chastanet A., Prudhomme M., Claverys J. P., Msadek T. (2001). Regulation of Streptococcus pneumoniae clp genes and their role in competence development and stress survival. J Bacteriol 183, 7295–7307. 10.1128/JB.183.24.7295-7307.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattoraj P., Banerjee A., Biswas S., Biswas I. (2010). ClpP of Streptococcus mutans differentially regulates expression of genomic islands, mutacin production, and antibiotic tolerance. J Bacteriol 192, 1312–1323. 10.1128/JB.01350-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng D. M., ten Cate J. M., Crielaard W. (2007). The adaptive response of Streptococcus mutans towards oral care products: involvement of the ClpP serine protease. Eur J Oral Sci 115, 363–370. 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2007.00477.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPersio J. R., Mattingly S. J., Higgins M. L., Shockman G. D. (1978). A quantitative ultrastructural and chemical investigation of the accumulation of iodophilic polysaccharide in two cariogenic strains of Streptococcus mutans. Microbios 21, 109–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frees D., Qazi S. N., Hill P. J., Ingmer H. (2003). Alternative roles of ClpX and ClpP in Staphylococcus aureus stress tolerance and virulence. Mol Microbiol 48, 1565–1578. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03524.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frees D., Chastanet A., Qazi S., Sørensen K., Hill P., Msadek T., Ingmer H. (2004). Clp ATPases are required for stress tolerance, intracellular replication and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol 54, 1445–1462. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04368.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frees D., Savijoki K., Varmanen P., Ingmer H. (2007). Clp ATPases and ClpP proteolytic complexes regulate vital biological processes in low GC, Gram-positive bacteria. Mol Microbiol 63, 1285–1295. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05598.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillot O., Pellegrini E., Bregenholt S., Nair S., Berche P. (2000). The ClpP serine protease is essential for the intracellular parasitism and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol 35, 1286–1294. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01773.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons R. J., Socransky S. S. (1962). Intracellular polysaccharide storage by organisms in dental plaques: its relation to dental caries and microbial ecology of the oral cavity. Arch Oral Biol 7, 73–79. 10.1016/0003-9969(62)90050-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman S. (2003). Proteolysis in bacterial regulatory circuits. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 19, 565–587. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.110701.153228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale J. D., Ting Y. T., Jack R. W., Tagg J. R., Heng N. C. (2005). Bacteriocin (mutacin) production by Streptococcus mutans genome sequence reference strain UA159: elucidation of the antimicrobial repertoire by genetic dissection. Appl Environ Microbiol 71, 7613–7617. 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7613-7617.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håvarstein L. S., Diep D. B., Nes I. F. (1995). A family of bacteriocin ABC transporters carry out proteolytic processing of their substrates concomitant with export. Mol Microbiol 16, 229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim Y. M., Kerr A. R., Silva N. A., Mitchell T. J. (2005). Contribution of the ATP-dependent protease ClpCP to the autolysis and virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun 73, 730–740. 10.1128/IAI.73.2.730-740.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenal U., Hengge-Aronis R. (2003). Regulation by proteolysis in bacterial cells. Curr Opin Microbiol 6, 163–172. 10.1016/S1369-5274(03)00029-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajfasz J. K., Martinez A. R., Rivera-Ramos I., Abranches J., Koo H., Quivey R. G., Jr, Lemos J. A. (2009). Role of Clp proteins in expression of virulence properties of Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 191, 2060–2068. 10.1128/JB.01609-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajfasz J. K., Rivera-Ramos I., Abranches J., Martinez A. R., Rosalen P. L., Derr A. M., Quivey R. G., Lemos J. A. (2010). Two Spx proteins modulate stress tolerance, survival, and virulence in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 192, 2546–2556. 10.1128/JB.00028-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreth J., Merritt J., Shi W., Qi F. (2005). Co-ordinated bacteriocin production and competence development: a possible mechanism for taking up DNA from neighbouring species. Mol Microbiol 57, 392–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreth J., Hung D. C., Merritt J., Perry J., Zhu L., Goodman S. D., Cvitkovitch D. G., Shi W., Qi F. (2007). The response regulator ComE in Streptococcus mutans functions both as a transcription activator of mutacin production and repressor of CSP biosynthesis. Microbiology 153, 1799–1807. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/005975-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon H. Y., Ogunniyi A. D., Choi M. H., Pyo S. N., Rhee D. K., Paton J. C. (2004). The ClpP protease of Streptococcus pneumoniae modulates virulence gene expression and protects against fatal pneumococcal challenge. Infect Immun 72, 5646–5653. 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5646-5653.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau P. C., Sung C. K., Lee J. H., Morrison D. A., Cvitkovitch D. G. (2002). PCR ligation mutagenesis in transformable streptococci: application and efficiency. J Microbiol Methods 49, 193–205. 10.1016/S0167-7012(01)00369-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemme A., Sztajer H., Wagner-Döbler I. (2010). Characterization of mleR, a positive regulator of malolactic fermentation and part of the acid tolerance response in Streptococcus mutans. BMC Microbiol 10, 58. 10.1186/1471-2180-10-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos J. A., Burne R. A. (2002). Regulation and physiological significance of ClpC and ClpP in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 184, 6357–6366. 10.1128/JB.184.22.6357-6366.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos J. A., Burne R. A. (2008). A model of efficiency: stress tolerance by Streptococcus mutans. Microbiology 154, 3247–3255. 10.1099/mic.0.2008/023770-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos J. A., Nascimento M. M., Lin V. K., Abranches J., Burne R. A. (2008). Global regulation by (p)ppGpp and CodY in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 190, 5291–5299. 10.1128/JB.00288-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. H., Lau P. C., Lee J. H., Ellen R. P., Cvitkovitch D. G. (2001). Natural genetic transformation of Streptococcus mutans growing in biofilms. J Bacteriol 183, 897–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loesche W. J. (1986). Role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decay. Microbiol Rev 50, 353–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez A. R., Abranches J., Kajfasz J. K., Lemos J. A. (2010). Characterization of the Streptococcus sobrinus acid-stress response by interspecies microarrays and proteomics. Mol Oral Microbiol 25, 331–342. 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2010.00580.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashburn-Warren L., Morrison D. A., Federle M. J. (2010). A novel double-tryptophan peptide pheromone controls competence in Streptococcus spp. via an Rgg regulator. Mol Microbiol 78, 589–606. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07361.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto-Nakano M., Kuramitsu H. K. (2006). Role of bacteriocin immunity proteins in the antimicrobial sensitivity of Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 188, 8095–8102. 10.1128/JB.00908-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano S., Nakano M. M., Zhang Y., Leelakriangsak M., Zuber P. (2003). A regulatory protein that interferes with activator-stimulated transcription in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100, 4233–4238. 10.1073/pnas.0637648100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooshima T., Matsumura M., Hoshino T., Kawabata S., Sobue S., Fujiwara T. (2001). Contributions of three glycosyltransferases to sucrose-dependent adherence of Streptococcus mutans. J Dent Res 80, 1672–1677. 10.1177/00220345010800071401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. A., Cvitkovitch D. G., Lévesque C. M. (2009a). Cell death in Streptococcus mutans biofilms: a link between CSP and extracellular DNA. FEMS Microbiol Lett 299, 261–266. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01758.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. A., Jones M. B., Peterson S. N., Cvitkovitch D. G., Lévesque C. M. (2009b). Peptide alarmone signalling triggers an auto-active bacteriocin necessary for genetic competence. Mol Microbiol 72, 905–917. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06693.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi F., Chen P., Caufield P. W. (2001). The group I strain of Streptococcus mutans, UA140, produces both the lantibiotic mutacin I and a nonlantibiotic bacteriocin, mutacin IV. Appl Environ Microbiol 67, 15–21. 10.1128/AEM.67.1.15-21.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T. (1989). Molecular Cloning: a Laboratory Manual, 2nd edn Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng J., Marquis R. E. (2007). Malolactic fermentation by Streptococcus mutans. FEMS Microbiol Lett 272, 196–201. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00744.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng J., Baldeck J. D., Nguyen P. T., Quivey R. G., Jr, Marquis R. E. (2010). Alkali production associated with malolactic fermentation by oral streptococci and protection against acid, oxidative, or starvation damage. Can J Microbiol 56, 539–547. 10.1139/W10-039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spatafora G., Rohrer K., Barnard D., Michalek S. (1995). A Streptococcus mutans mutant that synthesizes elevated levels of intracellular polysaccharide is hypercariogenic in vivo. Infect Immun 63, 2556–2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmoen H., Teigen A., Håvarstein L. S. (2003). Competence-induced cells of Streptococcus pneumoniae lyse competence-deficient cells of the same strain during cocultivation. J Bacteriol 185, 7176–7183. 10.1128/JB.185.24.7176-7183.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turlan C., Prudhomme M., Fichant G., Martin B., Gutierrez C. (2009). SpxA1, a novel transcriptional regulator involved in X-state (competence) development in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol 73, 492–506. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06789.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Ploeg J. R. (2005). Regulation of bacteriocin production in Streptococcus mutans by the quorum-sensing system required for development of genetic competence. J Bacteriol 187, 3980–3989. 10.1128/JB.187.12.3980-3989.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Houte J., de Moor C. E., Jansen H. M. (1970). Synthesis of iodophilic polysaccharide by human oral streptococci. Arch Oral Biol 15, 263–266. 10.1016/0003-9969(70)90084-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunder D., Bowen W. H. (2000). Effects of antibodies to glucosyltransferase on soluble and insolubilized enzymes. Oral Dis 6, 289–296. 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2000.tb00141.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Banerjee A., Biswas I. (2009). Transcription of clpP is enhanced by a unique tandem repeat sequence in Streptococcus mutans. J Bacteriol 191, 1056–1065. 10.1128/JB.01436-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuber P. (2004). Spx-RNA polymerase interaction and global transcriptional control during oxidative stress. J Bacteriol 186, 1911–1918. 10.1128/JB.186.7.1911-1918.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]