Abstract

Release of conventional neurotransmitters is mainly controlled by calcium (Ca2+) influx via high-voltage-activated (HVA), Cav2, channels (“N-, P/Q-, or R-types”) that are opened by action potentials. Regulation of transmission by subthreshold depolarizations does occur, but there is little evidence that low-voltage-activated, Cav3 (“T-type”), channels take part. GABA release from cortical perisomatic-targeting interneurons affects numerous physiological processes, and yet its underlying control mechanisms are not fully understood. We investigated whether T-type Ca2+ channels are involved in regulating GABA transmission from these cells in rat hippocampal CA1 using a combination of whole-cell voltage-clamp, multiple-fluorescence confocal microscopy, dual-immunolabeling electron-microscopy, and optogenetic methods. We show that Cav3.1, T-type Ca2+ channels can be activated by α3β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) that are located on the synaptic regions of the GABAergic perisomatic-targeting interneuronal axons, including the parvalbumin-expressing cells. Asynchronous, quantal GABA release can be triggered by Ca2+ influx through presynaptic T-type Ca2+ channels, augmented by Ca2+ from internal stores, following focal microiontophoretic activation of the α3β4 nAChRs. The resulting GABA release can inhibit pyramidal cells. The T-type Ca2+ channel-dependent mechanism is not dependent on, or accompanied by, HVA channel Ca2+ influx, and is insensitive to agonists of cannabinoid, μ-opioid, or GABAB receptors. It may therefore operate in parallel with the normal HVA-dependent processes. The results reveal new aspects of the regulation of GABA transmission and contribute to a deeper understanding of ACh and nicotine actions in CNS.

Introduction

Ca2+ influx through presynaptic high-voltage-activated (HVA) (Cav2) channels is predominantly responsible for release of conventional neurotransmitters (Augustine et al., 2003; Neher and Sakaba, 2008). Inhibition of these channels is the major mechanism of regulation of neurotransmitter release by G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) on synaptic terminals (Tedford and Zamponi, 2006). Low-voltage-activated (Cav3, T-type) Ca2+ channels are generally not involved in evoked neurotransmitter release, although they initiate slow release from nonaxonal sites (Carbone et al., 2006; Cueni et al., 2009). T-type Ca2+ channels differ markedly from HVA channels and if present could confer distinctive properties on synaptic transmission at conventional synapses.

Although HVA channels dominate the release process driven by axonal action potentials, other processes, including modulation by presynaptic neurotransmitter receptors, also regulate release. Presynaptic receptors in the brain are frequently located outside of defined synaptic regions. Indeed, much chemical signaling between neurons occurs “nonsynaptically” (Vizi and Lendvai, 1999), with transmitter being released from sites not apposed to postsynaptic targets and reaching receptors on distant presynaptic nerve terminals. For example, acetylcholine (ACh) influences numerous physiological and pathological processes in the CNS through activation of presynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) (Albuquerque et al., 2009) that modulate transmitter release (McGehee and Role, 1996; MacDermott et al., 1999). Numerous interneurons express nAChRs (McQuiston and Madison, 1999; Sudweeks and Yakel, 2000), and in cortical regions, perisomatic-targeting interneurons, mainly “basket cells,” control principal cell excitability and electrical oscillations implicated in cognitive processing (Klausberger et al., 2005; Freund and Katona, 2007). The links among nicotine and ACh in schizophrenia, memory and learning, and Alzheimer's disease (Albuquerque et al., 2009) make it important to understand regulation of perisomatic cell output by nAChRs.

Ca2+ permeation through the α7 nAChR pore induces glutamate release independently of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Sharma and Vijayaraghavan, 2003). Non-α7 nAChRs can elicit GABA release from synaptosomes (Wonnacott, 1997; Lu et al., 1998) and some brain regions (Léna and Changeux, 1997; Kawa, 2007; Liu et al., 2007), although the mechanisms of this effect are not well established. Presynaptic nAChRs might be capable of depolarizing synaptic terminals enough to induce release via activation of T-type Ca2+ channels; however, this possibility has received little attention.

We investigated cholinergic regulation of GABA release by activating hippocampal perisomatic GABAergic terminals with focal microiontophoretic ACh application. With a combined electrophysiological, morphological, and optogenetic approach, we find that activation of axonal α3β4 nAChRs can stimulate TTX-insensitive GABA release independently of HVA channels, via a mechanism that depends on Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ from internal stores. This mechanism can be found on parvalbumin (PV)-expressing, perisomatic-targeting interneurons, which are involved in pacing “gamma” rhythm oscillations (Freund, 2003; Klausberger et al., 2005; Bartos et al., 2007; Freund and Katona, 2007; Klausberger and Somogyi, 2008) and are implicated in schizophrenia (Lewis et al., 2005). nAChR-evoked IPSCs can inhibit pyramidal cells but are resistant to inhibition by agonists of cannabinoid receptors (CB1Rs), μ-opioid receptors (μORs), or GABAB receptors (GABABRs). The α3β4 nAChR-Cav3.1 mechanism could act in parallel with Cav2 channels and GPCRs and regulate GABA release.

Materials and Methods

All animal protocols were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM).

Slice preparation

Young (5- to 7-week-old) male Sprague Dawley rats (or virus-infected mice, below) were deeply sedated with isoflurane (2% in O2) and decapitated. Transverse hippocampal slices (400 μm thick) were cut on a Vibratome VT1200S (Leica). Slices were placed in a holding chamber at room temperature (22°C) at the interface of artificial CSF (ACSF) and a humidified gas mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2 for ≥1 h before use. ACSF contained the following (in mm): 120 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 MgSO4, 2.5 CaCl2, 1 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 20 glucose, and was bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2, pH 7.3.

Electrophysiology

Experiments were performed in a submersion-type tissue chamber (model RC-27; Warner Instruments) that was continuously perfused with ACSF at room temperature, ∼22°C. In all experiments on ACh-evoked GABA release, the voltage-clamped pyramidal cell was filled with the following (in mm): 80 Cs methanesulfonate, 50 CsCl, 10 HEPES, 3 ATP-Mg, 0.3 GTP-Tris, 0.1 CaCl2, 1 BAPTA-K4, 1 MgCl2, 5 QX-314; 280–290 mOsm, pH 7.2. Access resistance (Ra) was monitored on every sweep, and if Ra changed by >25%, the records were not used. To measure action potential firing (see Fig. 7), current-clamp recordings were made from pyramidal cells with patch pipettes containing the following (in mm): 146 K-gluconate, 1 NaCl, 1 MgSO4, 0.2 CaCl2, 2 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 4 ATP-Mg, 0.3 mm GTP-Tris. This solution preserved the normal GABAAR reversal potential of approximately −75 mV. A Nikon E600 microscope fitted with differential interference contrast optics was used for visually guided patch electrode placement, although in some experiments the “blind” patch method was used. Recordings were made with Axopatch 200B amplifiers (Molecular Devices). Signals were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 5 kHz with a Digidata 1440A interface and Clampex 10. Spontaneous IPSC frequency was measured with Mini-Analysis (Synaptosoft). The miniature IPSC (mIPSC) peak threshold value was from 6 to 8 pA (measured from the baseline determined from the 2.5 ms period just before the mIPSC) depending on the cell, and an mIPSC area threshold of 50 fC was set. Each mIPSC detection was visually verified. Timing of action potential firing (see Fig. 7) was analyzed with protocols written in Interactive Data Language (IDL5.5; Research Systems). In all other experiments, Clampfit 10 (Molecular Devices) was used to measure amplitude, total charge, and temporal properties of ACh-evoked responses.

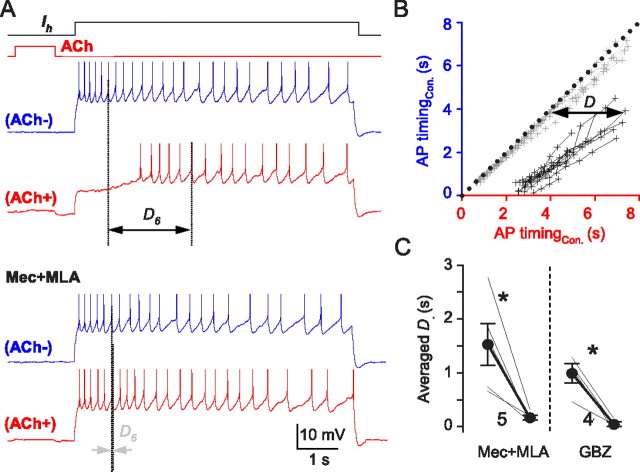

Figure 7.

ACh-induced GABA release suppresses pyramidal cell firing; TTX absent in all experiments. A, Action potentials evoked by depolarizing current injection into a pyramidal cell (blue traces; ACh−). One second ACh applications were timed to end 0.5 s before the pyramidal cell was depolarized. ACh greatly delayed the onset of action potential firing (red trace; ACh+). ACh effects were reversed by MLA (50 nm) plus Mec (1 μm) (bottom red trace; ACh+). D6 denotes the time between the occurrence of the sixth action potential induced by the current injection following the ACh pulse (ACh+) and its occurrence in control (ACh−). MLA plus Mec abolished D6. B, Plot of the occurrence of action potential firing induced by prolonged depolarizing current pulses from a typical cell, as in A. ACh was delivered before alternate traces, either in control solution or in Mec plus MLA. The plot was constructed by taking action potentials in pairs from trials from a given cell. The time of occurrence of the nth action potential in the series evoked by the depolarizing pulse alone (ACh−; blue traces in A) was plotted against the time of occurrence of the nth action potential on the following trial which was preceded by ACh application (ACh+; red traces in A). That is, the time of occurrence of the first action potential without ACh delivery is paired with the time of occurrence of the first action potential after ACh application in the following trial, the second is paired with the second, etc. Each action potential pair is indicated by one dot plotted against its time of occurrence after the start of the depolarization (time 0); dots representing the action potential pairs in the same trial (ACh−, ACh+) are connected by lines. Action potential pairs occurring at the same time after the start of the depolarization fall along a line with a slope of 1 passing through the origin (black dots). Action potential firing was systematically delayed during the ACh+ response in control solution; however, Mec plus MLA prevented the delay and the points (gray dots and lines) scatter around the black dotted line. The slopes of the lines are the same in both conditions, suggesting that the delay was not caused by changes in postsynaptic cell properties. C, Group data showing that the ACh-induced D values were reduced to near zero by MLA plus Mec or by gabazine. *p < 0.05.

Drug application

ACh was delivered locally with microiontophoretic pulses through a normal glass pipette containing 20 mm ACh and placed within 10–20 μm of the recorded pyramidal cell. A constant backing current of −15 nA prevented ACh leakage, and brief (0.5–1.5 s) positive currents of 300–500 nA were applied at intervals of 1–1.5 min to eject ACh. All other agonists or antagonists were bath-applied for >10 min. Nifedipine, 1,4-dihydro-2,6-dimethyl-5-nitro-4-[2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-3-pyridinecarboxylic acid, methyl ester (Bay K 8644), and 2,5-dimethyl-4-[2-(phenylmethyl)benzoyl]-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxylic acid methyl ester (FPL 64176) were dissolved in ethanol. 3,5-Dichloro-N-[1-(2,2-dimethyl-tetrahydro-pyran-4-ylmethyl)-4-fluoro-piperidin-4-ylmethyl]-benzamide (TTA-P2), ryanodine, cyclopiazonic acid (CPA), xestospongin C, and (R)-(+)-[2,3-dihydro-5-methyl-3-(4-morpholinylmethyl)pyrrolo[1,2,3-de]-1,4-benzoxazin-6-yl]-1-napthalenylmethanone (WIN 55212-2) were dissolved in DMSO. Final concentrations of both vehicles were <0.1%. EGTA-AM was dissolved in DMSO at 50 mm and an equal volume of 20% Pluronic F-127 (Sigma-Aldrich; in DMSO) before dilution in ACSF. The combination of 0.4% DMSO and 0.08% Pluronic F-127 alone did not affect ACh-evoked responses. α-Conotoxin AuIB synthesis has been described previously (Luo et al., 1998) and was provided by J.M.M.; TTA-P2 was provided by V.N.U. and J.J.R.; NBQX, APV, and TTX were obtained from Ascent Scientific; EGTA-AM was obtained from Invitrogen; and other drugs used were purchased from Tocris or Sigma-Aldrich.

Intrinsic flavoprotein fluorescence imaging

Redox fluorometry based on intrinsic fluorescence of oxidized flavoproteins has been used for studying cellular energy metabolism (Shibuki et al., 2003). We used changes in intrinsic flavoprotein fluorescence to estimate the functionally effective spread of ACh released by microiontophoresis. The fluorescence was excited at 450–490 nm by a mercury lamp and monitored via a 505LP dichroic mirror and a 510–560 nm emission filter through a 60× water-immersion objective. Images were acquired with a monochrome CCD camera (ORCA; Hamamatsu) at 20 Hz. Data were recorded with 8 × 8 binning with Metafluor software (Molecular Devices). Imaging files were analyzed with customized IDL protocols.

Preparation of AAV vectors

The plasmids pAAV-EF1a-double floxed-hChR2 (H134R)-mCherry-WPRE-HGHpA and pAAV-EF1a-double floxed-mCherry-WPRE-HGHpA (K. Deisseroth, Stanford University, Stanford, CA; Addgene stock 20297 and 20299, respectively) were packaged into AAV pseudotyped vectors (1:1 ratio of AAV1 and AAV2 capsid proteins, with AAV2 inverted-terminal repeats) by methods that have been described previously (Klugmann et al., 2005). The genes encoding mCherry or ChR2-mCherry in these vectors are inverted in the antisense direction and are under the control of a Cre-dependent flip-excision (“FLEX”) switch. Activation of the FLEX switch results in stable gene inversion into the sense direction, and thus gene expression, only in the presence of Cre (Atasoy et al., 2008).

Transgenic mice and AAV injection

ChAT-Cre (B6;129S6-Chattm1(cre)Lowl/J) and PV-Cre (B6;129P2-Pvalbtm1(cre)Arbr/J) transgenic mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (stock 006410 and 008069, respectively). Homozygous mice were bred and maintained in the animal facility at the UMSOM. Mice were housed on a 12 h light/dark cycle with food and water ad libitum.

Adult (7- to 16-week-old) mice were anesthetized with ketamine (75 mg/kg) and acepromazine (2.5 mg/kg). They were placed in a small-animal stereotactic instrument (David Kopf Instruments). A small craniotomy was made over the target region with a dental drill, and a glass pipette (tip diameter, ∼50 μm) was used to inject a total volume of 0.5–1 μl of AAV (5 × 109 genome copies/μl) at 0.1 μl/min into the medial septum/diagonal band of Broca of ChAT-Cre mice (+1.0 mm AP from bregma, 0.0 mm L, −4.2 to −3.2 mm DV from the dura) or bilaterally into the dorsal hippocampi of PV-Cre mice (−2.0 mm AP from bregma, ±1.5 mm L, −1.3 to −1 mm DV from the dura) using a microinjection pump (KD Scientific). The total volume of virus was ejected in portions over several sites along the dorsoventral axis to achieve optimal coverage of the target region. The pipette was left in place for 3 min after each injection before the craniotomy was sealed and the incision sutured. PV-Cre mice recovered in the animal facility for >4 weeks, and Chat-Cre mice for >5 weeks, before experiments.

Optogenetic experiments

For excitation of ChR2, square pulses of blue light (450–490 nm, 5 ms) from a 100 W mercury lamp (Nikon C-SHG1) were delivered through the 60× water-immersion objective of a Nikon E600 microscope equipped with fluorescence filter sets. To set light pulse and train duration, a high-speed shutter (Uniblitz VMM-D1; Vincent Associates) was controlled by a Pulsemaster A300 digital timer (World Precision Instruments), which was triggered by Clampex 10 (Molecular Devices). mCherry was visualized under 557–597 nm light, which did not activate ChR2 in the somata of septal cholinergic cells.

Morphological experiments

Tissue preparation.

Male Sprague Dawley rats (n = 7; P35–P50) were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (150 mg/kg, i.p.) and perfused via the ascending aorta with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate buffer (PB) for immunofluorescence, or 3.75% acrolein in 2% PFA in PB for electron microscopy (EM). Brains were removed and tissue was postfixed (4% PFA or 1.87% acrolein/2% PFA in PB) overnight at 4°C. Coronal sections (40 μm thick) were cut on a vibratome (Leica) in chilled PB, and then treated with 1% sodium borohydride in 0.1 m PB for 30 min and permeabilized with Triton X for immunofluorescence or freeze-thawed for EM. Sections were rinsed in PB followed by 0.02 m KPBS for immunofluorescence or Tris-buffered saline (TS), pH 7.6 (for EM), and blocked (normal goat serum and normal horse serum, 1:100), and 0.03% Triton X in KPBS for 1 h at room temperature for immunofluorescence labeling, or in 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TS for 30 min for EM.

Antisera.

Antibody dilutions, sources, and related references are shown in Table 1. We used a well documented antibody (Ernst et al., 2009), which has been validated against the Cav3.1 knock-out mouse by T. Snutch (personal communication). To confirm antibody specificity, control experiments included slice treatment: (1) without the primary antibody, (2) without the secondary antibody, and (3) for Cav3.1 with the antibody that had been incubated for 2 h at room temperature with 1 μg of the preimmune peptide (Alomone). Selective immunoresponsivity was not visible after any control treatment.

Table 1.

Primary antibodies, dilutions, and sources used in experiments (see Materials and Methods), a sample reference in which the specificity of the antibody has been demonstrated, and the method used to validate the specificity of the antibody

| Molecule | Species | Dilution | Source | Specificity references | Validation method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV | Mouse IgG | 1:10,000 1:3000 (EM) | Swant, PV-28 | Celio et al., 1988 | Immunoblot of brain and muscle lysates |

| Rabbit IgG (used for PVCre mice) | 1:1000 | Calbiochem, PC255L | Mithani et al., 1987 | Western blot of rat brain and muscle lysates | |

| SYP | Mouse IgM | 1:5000 | Millipore, mab sp15 | Honer et al., 1993 | Immunoblot of human brain lysates |

| Cav3.1 | Rabbit IgG | 1:100 | Alomone, ACC-021 | Ernst et al., 2009 | Western blot of brain lysates from transgenic mice overexpressing receptor; validated against Cav3.1 KO mouse (T. Snutch, personal communication) |

| TAU1 | Mouse IgG | 1:5000 | Millipore, mab3420 | Binder et al., 1985 | Immunoblot of rat brain lysates |

| ChAT | Goat IgG | 1:1000 | Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents, AB144P | Raised against human placental enzyme; company tested | Western blot of mouse brain lysates |

Immunohistochemistry.

After blocking, slices were incubated overnight at room temperature in a mixture of primary antibodies in KPBS. Following incubation, the sections were washed in KPBS (30 min) and incubated for 1 h in biotinylated anti-rabbit antibody (Vector; 1:500). The slices were rinsed several times in KPBS for 30 min and incubated in 1:400 dilutions of anti-mouse IgM conjugated to Cy5 (Jackson ImmunoResearch), anti-mouse IgG conjugated Texas Red (Vector), and avidin-FITC (Vector) for 1 h (in the dark). The slices were rinsed again in KPBS, and then mounted in Vectashield with DAPI (Vector).

Analysis of immunofluorescence labeling.

Imaging was done on a Nikon microscope (Eclipse 80i) equipped with an OptiGrid structured light device (Qioptiq Imaging Solutions) as part of a Volocity Grid Confocal system (Improvision). FITC was excited at 495 nm (pseudocolored green), emission at 515 nm; Texas Red (pseudocolored red) was excited at 595 nm, emission at 620 nm; and Cy5 was excited at 645 nm, emission at 705 nm (pseudocolored blue). Z-stacks of individual channels were captured with a monochrome CCD camera (Hamamatsu ORCA ER).

The Volocity software can convert z-stack images (obtained at 100× magnification) into a single 3-D volume (8 μm thick) that can be optically rotated, and each color channel independently monitored. The image frame size was 1024 × 1024 pixels. The z-axis step size was 0.2 μm, the voxel dimension was 0.07 × 0.07 × 0.2 μm (x–z, respectively). Exposure times were set by the Volocity “auto exposure” function. After noise removal (with a 3 × 3 × 3 median filter), the mean background intensity was calculated for each volume. Objects five or more times brighter than the background at least four voxels in size were counted.

Axons displayed Tau1 or synaptophysin immunoreactivity. Stretches of >5 μm of contiguously stained axon were examined for Cav3.1 immunopositivity. When putative Cav3.1 staining was observed, the volume was rotated 360° around its axes to determine whether or not the staining was in contact with axon within the limits of resolution (∼70 nm). Cav3.1 labeling on PV-axons lengths >4 μm, which also contained synaptophysin staining, were analyzed.

Immuno-electron microscopy.

For EM localization of Cav3.1 in perisomatic-targeting interneurons, sections were dual labeled for PV and Cav3.1. According to published procedures (cf. Karson et al., 2009), sections were incubated in anti-CaV3.1 and anti-PV antisera in 0.1% BSA in TS for 1 d at room temperature followed by a 2 d incubation at 4°C. For PV immunoreactivity, sections were incubated in biotinylated donkey-anti-mouse IgG (Vector) and processed with an ABC peroxidase technique. For Cav3.1 labeling, sections were rinsed in TS and incubated in goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to 1 nm gold particles (1:50; Electron Microscopy Sciences) in 0.08% BSA and 0.01% gelatin in 0.01 m PBS, pH 7.4, at room temperature for 2 h. Sections were rinsed in PBS, postfixed in 2% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 10 min, and rinsed in PBS followed by 0.2 m sodium citrate buffer, pH 7.4. The conjugated gold particles were enhanced by treatment with silver solution (IntenSE; GE Healthcare) for 10 min. For confirmation, the labeling was also performed with Cav3.1 labeled with immunoperoxidase and PV labeled with immunogold.

Sections were postfixed for 1 h in 2% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated through alcohols and propylene oxide, and embedded between two sheets of plastic in EMbed 812 (EMS). Seventy-nanometer-thick sections were cut on an ultratome (Ultracut; Leica) and counterstained with uranyl acetate and Reynold's lead citrate. Images were obtained with a FEI Tecnai Biotwin transmission electron microscope and corrected for brightness and contrast with Adobe Photoshop CS4 (Adobe Systems).

Analysis of EM data.

Tissue from the pyramidal cell layers of three animals was thin sectioned, and EM images from the tissue surface were analyzed. Profiles were considered to be double labeled if they contained electron-dense, peroxidase reaction precipitate and one or more gold particle. All profiles dual labeled for both PV and Cav3.1 were photographed and classified as somata, dendrites, spines, axons, or terminals (excitatory or inhibitory) using morphological criteria (Peters et al., 1991).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses performed with SigmaPlot 8.0 or SigmaStat 3.0. Data are given as mean ± SEM. Two-tailed paired t tests or ANOVA were used; significance levels are indicated.

Results

Focal ACh application causes bursts of mIPSCs in pyramidal cells

We first asked whether focal microiontophoretic ACh application could be used to probe the mechanisms of regulation of GABA release from perisomatic-targeting interneurons in CA1. The highly Ca2+-permeable α7 nAChRs are extensively expressed in somatodendritic regions of many CA1 interneurons (Khiroug et al., 2003) and on glutamatergic axon terminals (Sharma and Vijayaraghavan, 2003; Sharma et al., 2008); however, it is not known which nAChRs are present on the perisomatic-targeting interneuron terminals. To investigate this question, we used focal microiontophoresis (0.5–1.5 s pulses) to apply ACh to GABAergic axons on or near pyramidal cell somata. Focal ACh evoked transient barrages of inward postsynaptic currents (Fig. 1A, black trace) that were resistant to NBQX (10 μm), APV (50 μm), and atropine (2 μm) (Fig. 2C), but were abolished by gabazine (Figs. 1A, blue trace; 2C). Reversed iontophoretic pulses (Fig. 1A) were ineffective. The results imply that ACh induced the release of GABA by activating nAChRs. NBQX, APV, and atropine were present in all subsequent experiments.

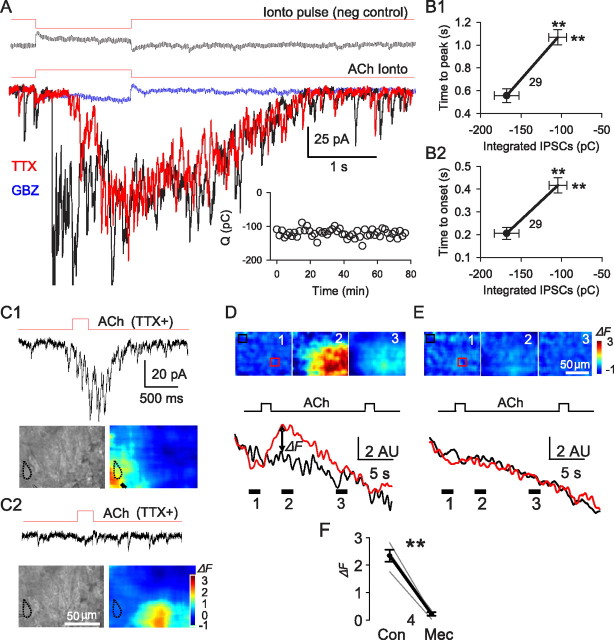

Figure 1.

Local ACh applications to perisomatic-targeting interneuron terminals evokes mIPSC bursts in pyramidal cells. A, Microiontophoretic application of ACh (indicated by red lines above traces) evoked postsynaptic currents in pyramidal cells. The top panel shows the response to an inverted iontophoretic pulse as a negative control. The bottom panel depicts typical responses to ACh in normal saline (black), TTX (red), and 10 μm gabazine (blue). The inset illustrates the stability of ACh response in TTX. Changes in time-to-peak (B1) and time-to-onset (B2) of the responses as functions of the magnitudes of the integrated ACh responses (in picocoulombs) before (filled circles) and after (open ends of lines) TTX application (means ± SEMs). In this and all subsequent figures, the numbers in the figure denote the group sizes. C, D, Areas of effective ACh action assessed by local changes of intrinsic flavoprotein fluorescence (see Materials and Methods). All experiments were done in the presence of TTX. C1, ACh delivered close to a recorded pyramidal cell (outlined in dotted black line) induced a burst of mIPSCs and a dramatic increase in flavoprotein fluorescence in a small region (red area) near the cell. C2, Delivery of ACh 50 μm away from the same cell as in C1 failed to evoke GABA release or a change in intrinsic fluorescence near the cell. The images were averaged from three consecutive trials. **p < 0.01. D, Images show distribution of fluorescence changes (ΔF) before, during, and after the ACh-induced F peak. The red and black traces below denote the averaged F within the red and white boxes, respectively. E, ΔF distribution before, during, and after the ACh application in the presence of 10 μm Mec. F, Group data; Mec blocks ACh-induced flavoprotein ΔF.

Figure 2.

ACh-evoked GABA release depends on activation of α3β4 nAChR. A, Example of the effects of 10 μm nicotine on an ACh-evoked mIPSC burst. B, Example of the effects of the selective α3β4 nAChR blocker, α-conotoxin AuIB (3 μm), and subsequent addition of the α7 nAChR blocker MLA (50 nm) on an ACh-evoked mIPSC burst. C, Pooled data showing effects of various drugs on integrated ACh-induced mIPSC bursts. D, Example of the effect of AuIB (3 μm) on an ACh-evoked IPSC burst in the absence of TTX. E, Pooled data showing the reversible blockade of ACh-induced responses by AuIB. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

ACh-evoked GABA release had an initial phase with many large (>50 pA) IPSCs, and a later phase that continued briefly after the end of the pulse and comprised summated small-amplitude currents (Fig. 1A, black trace). TTX eliminated the initial phase (Fig. 1A, red trace) but had no effect on the mIPSCs in the later phase. Thus, TTX delayed the onset latency and time-to-peak of the IPSC responses (Fig. 1B) but left their decay kinetics unaltered.

The TTX-resistant component of ACh-induced GABA responses accounted for 62.8 ± 5.3% of the total charge induced (n = 21). If its magnitude was >15 pC, the TTX-resistant response was considered a “burst” of mIPSCs. Because of extensive overlap of mIPSCs, the responses were quantified by integration of the area under the burst envelopes. Bursts were stable for >1.5 h when evoked at 1 or 1.5 min intervals (Fig. 1A, inset). mIPSC bursts were observed in 161 cells (i.e., 56%) of the 288 pyramidal cells tested. In the remainder, the ACh response was either absent or fully blocked by TTX. nAChR responses per se from CA1 pyramidal cells were not observed. TTX was present in the following experiments except as noted.

Location of the nAChRs on GABAergic nerve terminals

The occurrence of mIPSC bursts in the presence of TTX suggests that ACh acts relatively near the GABA release sites. The restricted spatial extent of the focal microiontophoretic ACh application was confirmed by the following: (1) withdrawal of the iontophoretic pipette by ∼50 μm, which abolished the mIPSC burst (Fig. 1C2) (cf. Karson et al., 2009); and (2) imaging the effective area of influence with intrinsic flavoprotein fluorescence (Shibuki et al., 2003), which revealed a confined zone of influence (Fig. 1C,D). Autofluorescence of mitochondrial flavoproteins represents the level of cellular energy metabolism. It is increased by neurotransmitter activation and hence indicates the effective spatial spread of applied ACh. In TTX, a 0.5 s ACh application elevated tissue fluorescence in a roughly circular area with a radius of ∼50 μm, and a radius of high concentration (≥80% of peak) of ∼10 μm (Fig. 1C). With a 1.5 s ACh pulse, the maximal radius was ∼75 μm and the high concentration radius ∼20 μm (Fig. 1D). The signals were nearly abolished by the nonselective nAChR antagonist mecamylamine (10 μm) (Fig. 1D). Thus, focal ACh microiontophoresis only activated nAChRs in stratum (s.) pyramidale near the synaptic or perisynaptic regions of the axons.

α3β4 nAChRs are the primary triggers of ACh-evoked mIPSC bursts

ACh-evoked mIPSC burst amplitudes were greatly reduced by bath application of a desensitizing concentration, 20 μm, of nicotine (to 27.7 ± 8.8% of baseline, p < 0.05, n = 5; responses recovered to 82.0 ± 13% of control with 10 min of washing; n.s., n = 3; Fig. 2A,C), confirming that nAChRs trigger them. Several pharmacological results are summarized in Figure 2C. Mecamylamine (10 μm) also reduced the ACh-induced bursts (to 17.8 ± 2.8% of baseline; p < 0.01; n = 11). Dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE) (10 μm), an antagonist of α4- or α6-containing nAChRs and α3β2 nAChRs (Harvey and Luetje, 1996), had no effect (p > 0.05; n = 10). The selective α7 nAChR antagonist methyllycaconitine (MLA) at 50 nm reduced the mIPSC bursts, but by only ∼15% (to 86.6 ± 5.4% of baseline; p < 0.05; n = 8) and the positive α7 nAChR allosteric modulator, N-(5-chloro-2,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-N′-(5-methyl-3-isoxazolyl)urea (PNU-120596), 1 μm, enhanced them (to 169.1 ± 20.8% of baseline; p < 0.05; n = 7), suggesting that α7 nAChRs play a modest role. (Asymmetry between the α7 nAChR antagonist and agonist effects is expected, because release is steeply related to Ca2+ influx, which will be increased by PNU-120596, even if α7 nAChRs are present at a relatively low density.) In contrast, the α3β4-nAChR-specific antagonist, α-conotoxin AuIB (AuIB) (Luo et al., 1998), 2 μm, reversibly reduced the mIPSC burst by ∼80% (to 21.2 ± 3.7% of baseline; p < 0.01, n = 7; recovery to 84.7 ± 13.9% with washing; n.s., n = 7; Fig. 2B,C). Adding 50 nm MLA to AuIB essentially abolished the remaining current (to 7.6 ± 2.0% of control; p < 0.05; n = 6; Fig. 2B,C). In the presence of MLA, AuIB also blocked the TTX-sensitive IPSCs (to 12.9 ± 1.6% of baseline; p < 0.01; n = 4; Fig. 2D,E; recovery to 85.5 ± 9.6% with washing; n.s.; n = 4), showing that action potential-dependent GABA release was also regulated by α3β4 nAChR. Although it appears that the nAChRs responsible for GABA release are on perisynaptic portions of axons in s. pyramidale, we also checked the possibility that focal ACh application might have activated somatodendritic α3β4 nAChRs by making whole-cell recordings from 24 CA1 interneurons (9 in s. radiatum and 15 in s. oriens). However, in the presence of the α7 nAChR antagonist, MLA, we did not detect any ACh response >2 mV, consistent with the conclusion that α7 nAChRs are principally expressed in the somatodendritic regions of these interneurons (Khiroug et al., 2003). Thus, axonal α3β4 nAChRs mainly account for the ACh-evoked mIPSC bursts, with a minor fraction due to α7 nAChRs. This might be significant because the Ca2+ permeability of α3β4 nAChRs accounts for only ∼3–4% of their total conductance (Ragozzino et al., 1998).

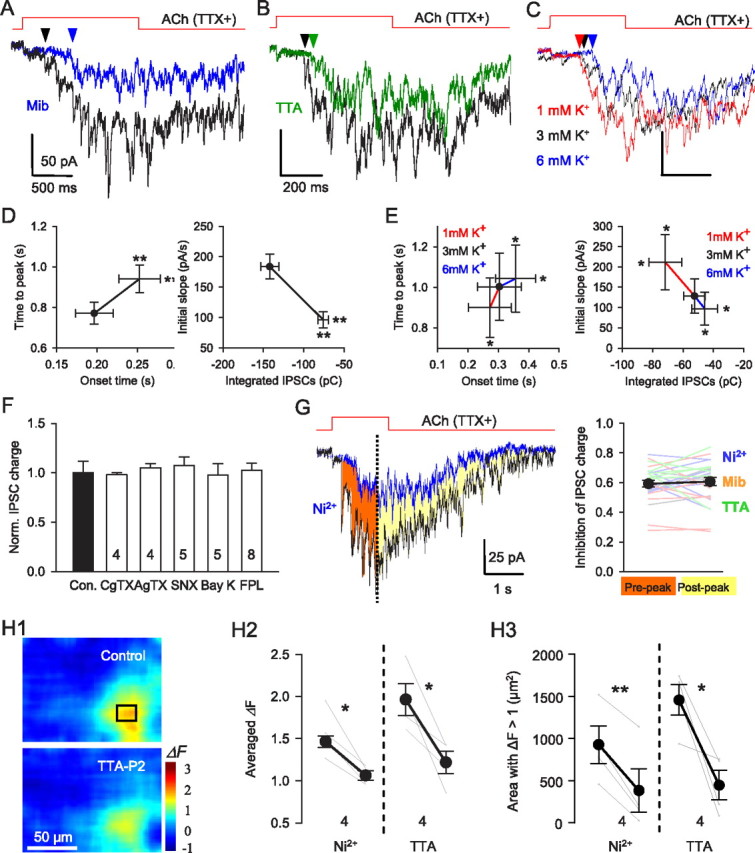

ACh-evoked GABA release mainly depends on Ca2+ influx through T-type Ca2+ channels

Elevating extracellular Ca2+ concentration from 2.5 to 5 mm greatly increased the mIPSC bursts (to 234 ± 36%; p < 0.01; n = 7), indicating the ACh effect is Ca2+ dependent. Ca2+ flux through nAChRs is generally not blocked by Cd2+ (Léna and Changeux, 1997; Sharma and Vijayaraghavan, 2003). The ACh-induced whole-cell currents of the human neuroblastoma cell line, IMR-32, are primarily mediated by α3β4 nAChRs (Nelson et al., 2001), so we used these cells as a bioassay for α3β4 nAChR-mediated effects. ACh was applied by focal microiontophoresis with the same parameters as used in slices. We confirmed that the IMR-32 currents were markedly reduced by the α3β4 nAChR antagonist AuIB (from 229 ± 47 pA to 36 ± 11 pA; n = 5 cells, p < 0.01). Cd2+ reportedly does not affect α3β4 nAChR currents in IMR-32 cells (Donnelly-Roberts et al., 1995), and we confirmed that Cd2+ (200 μm) had no significant effect on the IMR-32 cell current in our hands (mean reduction to 93.2 ± 5.7%; n.s.; n = 8). Nevertheless, in slices, 200 μm Cd2+ reversibly reduced the ACh-induced mIPSC bursts to 55.5 ± 3.3% of baseline (n = 12, p < 0.01; recovery to 102 ± 20%, n.s., n = 5, with washing), indicating that VGCCs are significantly involved. Notably, however, the specific toxin blockers of HVA channels typically associated with transmitter release—ω-ConoTX GVIA (500 nm), ω-AgaTX IVA (300 nm), or SNX 482 (100 nm), for N-, P/Q-, and R-type Ca2+ channels, respectively—did not affect the ACh-induced mIPSC bursts (Fig. 3F; all p > 0.05; n = 4–5 experiments for each toxin).

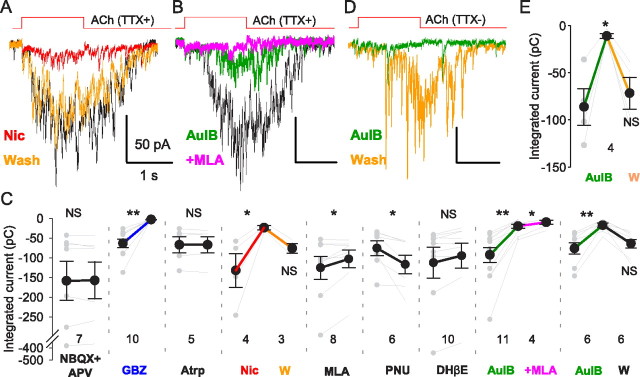

Figure 3.

ACh-evoked GABA release depends on opening of T-type Ca2+ channels. A, B, ACh-evoked mIPSC bursts in the presence of mibefradil (5 μm, blue) (A) or a specific T-type Ca2+ channel antagonist, TTA-P2 (3 μm, green) (B). T-type Ca2+ channel blockade by Ni2+, mibefradil, and TTA-P2 reduced the total charge, delayed the onset and time-to-peak and decreased the initial rising slope of ACh-evoked mIPSC bursts (D). C, ACh-evoked responses in presence of different [K+]o concentrations. Baselines were adjusted to make comparisons easier. E, Reducing [K+]o increased the total charge, accelerated the time-to-peak and enhanced the initial rising slope of ACh-evoked mIPSC burst. Elevating [K+]o had the opposite effects. F, ACh evoked mIPSC bursts were insensitive to antagonists of CaV2 channels (CgTX, ω-conotoxin GVIA; AgTX, ω-agatoxin IVA; SNX, SNX 482) or agonists of CaV1 channels (Bay K, Bay K8644; FPL, FPL 64176). G, T-type Ca2+ channel blockade suppressed ACh-evoked responses before (filled red area) or after (filled yellow area) the peak ACh-induced response to the same extent. Group data (n = 23) for experiments as in G (left). H1–H3, Flavoprotein fluorescence signals (ΔF) are blocked by T-type Ca2+ channel antagonists. H1, Image of ACh-induced ΔF in control condition (top) and in TTA-P2 (bottom). H2, Mean ACh-induced ΔF changes are reduced by 100 μm Ni2+ or 3 μm TTA. H3, Area of region with ΔF > 1 is reduced by Ni2+ or TTA. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Nifedipine (10 μm), an L-type (Cav1) Ca2+ channel blocker, slightly reduced ACh-induced burst (to 77.0 ± 6.5% of baseline; p < 0.05; n = 13), but the selective L-type Ca2+ channel agonists Bay K 8644 (1 μm; n = 5) and FPL 64176 (5 μm; n = 8) had no effect (Fig. 3F; both p > 0.05; n = 5) despite increasing whole-cell Ca2+ currents in control experiments. As this casts doubt on a role for L-type Ca2+ channels, we tested the remaining possibility that T-type Ca2+ channels were activated during the ACh responses. The T-type Ca2+ channel blocker mibefradil, 5 μm, reduced the ACh response (Fig. 3A,D; to 42.6 ± 5.0% of the total charge in nifedipine; p < 0.01; n = 11). At the concentration of 50 μm, Ni2+ blocks Cav2.3 (R-type Ca2+ channels) and Cav3.2-type T-type Ca2+ channels (Catterall et al., 2005) but did not affect the mIPSC burst (106.5 ± 4.6%; p > 0.05; n = 5), while at 100 μm, a concentration that depresses T-type Ca2+ currents mediated by Cav3.1 and Cav3.3 isoforms (Catterall et al., 2005), Ni2+ reversibly suppressed mIPSC bursts (to 64.7 ± 5.7% of baseline, p < 0.01, n = 12; recovery to 100 ± 37.1%, n.s., n = 5, with washing). ACh-induced currents in IMR-32 cells were resistant to Ni2+, 100 μm (to 100.7 ± 3.0%; n.s.; n = 4), and mibefradil (to 94.2 ± 4.6%; n.s.; n = 7), indicating that the α3β4 nAChRs are unaffected by these treatments as well.

Despite their efficacy in inhibiting the ACh-induced mIPSC bursts, mibefradil and low concentrations of Ni2+ are only relatively selective for T-type Ca2+ channels; therefore, we tested the selective T-channel antagonist, TTA-P2 (Shipe et al., 2008; Uebele et al., 2009; Dreyfus et al., 2010) at 3 μm, and found that it too reduced the ACh response (Fig. 3B,D; to 55.5 ± 8.3% of baseline, p < 0.01, n = 6). TTA-P2 did not affect the α3β4 nAChR currents in IMR-32 cells (to 98.4 ± 2.4% of baseline; n.s.; n = 5), supporting the interpretation that the TTA-P2 reduction of the ACh-induced GABA release in slices is mediated by its inhibition of T-type Ca2+ channels.

T-type Ca2+ channels are activated by small depolarizations from negative membrane potentials and inactivate at relatively negative potentials (Catterall et al., 2005). If the α3β4 nAChR-mediated response depends on T-type Ca2+ channels, it should be highly voltage dependent. To test this prediction, we changed the extracellular K+ concentration ([K+]o) from the normal 3 mm to 1 or 6 mm while recording from interneurons near the s. pyramidale/s. oriens border in the presence of TTX. It is not feasible to measure the membrane potential of the interneuronal synaptic terminals, where the T-type Ca2+ channels may be located. Therefore, to confirm the ability of changes in [K]o to alter neuronal properties, we used the interneuron soma as a surrogate and found that, as expected, membrane potentials were hyperpolarized (by 3.9 ± 0.4 mV) or depolarized (by 7.8 ± 0.9 mV), by 1 and 6 mm [K]o, respectively (n = 6). Assuming that the interneuron terminals were similarly affected, we tested the ACh-evoked mIPSC bursts and observed they were increased in 1 mm [K+]o and decreased in 6 mm [K+]o (Fig. 3C,E; both p < 0.05; n = 8). The results suggest that presynaptic GABAergic terminals were hyperpolarized or depolarized correspondingly and are consistent with the hypothesis that T-type Ca2+ channels played a role in the GABA release process. Although T-type Ca2+ channels are subject to voltage-dependent inactivation, they were apparently not inactivated by ACh application, as their contribution to the ACh-induced mIPSC burst remained constant throughout the response (Fig. 3G). Finally, T-type Ca2+ channel antagonists suppressed the increase in flavoprotein fluorescence (Fig. 3H), in agreement with the interpretation that they are activated by ACh application.

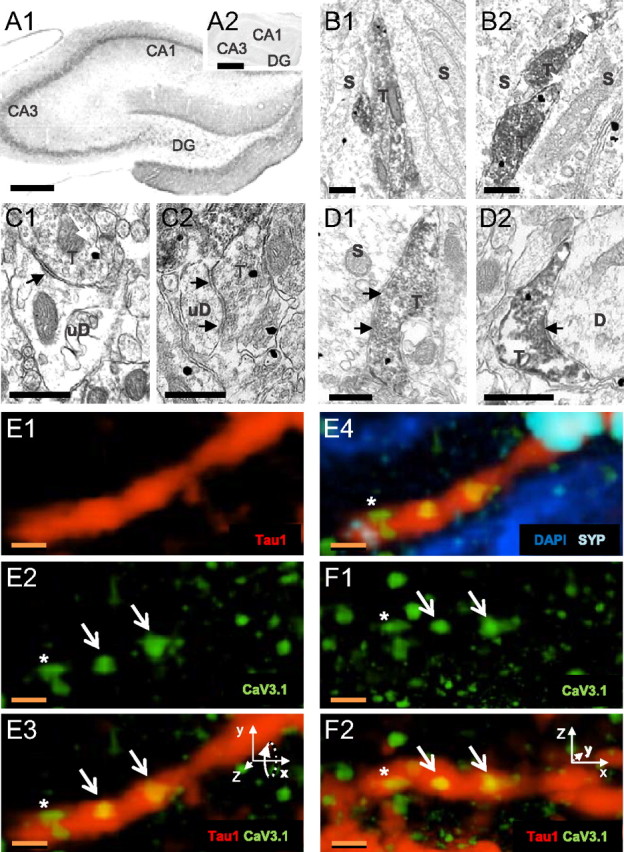

Morphological evidence for Cav3.1 on inhibitory axon terminals

Together, the physiological and pharmacological data are consistent with the hypothesis that Ca2+ influx through T-type Ca2+channels triggers a GABA release process that is initiated by activation of α3β4 nAChRs. Nevertheless, T-type Ca2+ channels have not generally been observed on terminal or preterminal axons in the mammalian brain (Catterall et al., 2005). We therefore used multifluorescence confocal immunohistochemistry and dual-labeling electron microscopy to test the prediction that T-type Ca2+ channels exist on and near GABAergic axonal release sites.

The Cav3.1 antibody yielded immunoreactivity throughout the hippocampus, as previously reported (McKay et al., 2006; Vinet and Sík, 2006). The specificity of this antibody has been validated (Kim et al., 2001); however, the available Cav3.3 antibody yields off-target labeling (Chen et al., 2007) and was not tested. At 20× magnification, Cav3.1 immunoreactivity was strongest in CA1 s. pyramidale, with intense labeling of pyramidal cell somata and proximal dendrites (Fig. 4A1). Interneuronal somata scattered throughout s. pyramidale, s. radiatum, and s. oriens also showed Cav3.1 immunoreactivity. No labeling was observed in slices treated with antibody plus preimmune peptide (compare Fig. 4A2).

Figure 4.

Cav3.1 channels are expressed on PV axons in CA1 s. pyramidale. A1, Hippocampal Cav3.1 immunostaining (4× magnification). A2, Cav3.1 immunolabeling is blocked by absorption in preimmune peptide. Scale bars, 200 μm. B–D, Electron micrographs of PV (peroxidase)- and Cav3.1 (immunogold)-labeled profiles in s. pyramidale. S, Soma, D, dendrite, T, terminal. Scale bars, 500 nm. B1, B2, Double-labeled profiles appose pyramidal somata. C1, C2, Cav3.1-labeled terminals make synaptic contacts (arrows) on dendrites. D1, D2, Double-labeled terminals make synaptic contacts (arrows) on pyramidal cell profiles. E1–E3, A Tau1-labeled axon (red) contains Cav3.1-immunoreactive puncta (green). Two large puncta are within the structure (E2, E3, arrows), and one is in close apposition (*). E4, The Tau1-labeled axon also contains synaptophysin (SYP) immunoreactivity (light blue). The Cav3.1 puncta not contained in the Tau1-labeled axon may be in neighboring somata (nuclei stained with DAPI, dark blue). F1, F2, Same as E2 and E3, rotated into the plane by 90° (note rotation of inset x–z coordinates). Cav3.1-immunoreactive puncta were within the axon even under rotation. Scale bars: E, F, 1 μm.

Ultrastructural evidence of presynaptic Cav3.1 expression

Because CCK interneurons predominantly express α7 nAChRs (Morales et al., 2008), the large, non-α7 nAChR-mediated responses probably originate from the non-CCK-perisomatic cells that express PV, and we therefore focused on this possibility. Slices were stained for PV and Cav3.1 (alternating immunoperioxidase and immunogold labeling for each antibody), and ultrathin sections of CA1 made. Within putative pyramidal cell and interneuronal somata and dendrites, Cav3.1-like immunoreactivity was visible throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 4B–D) of PV-labeled and unlabeled presynaptic axons (n = 191) and apparent (see Materials and Methods) inhibitory terminals (n = 254). Approximately 16% of all axons and ∼25% of all putative inhibitory terminals had Cav3.1 immunogold labeling. Of the immunoperoxidase-PV-labeled processes, 13% of the axons and 23% of the terminals also labeled for Cav3.1 immunogold. Dual (PV plus Cav3.1)-labeled terminals made contacts primarily on putative pyramidal cell somata or dendrites (Fig. 4C,D; Table 2). In the reverse configuration, when Cav3.1 was labeled with immunoperoxidase and PV was labeled with immunogold, both PV-labeled and -unlabeled axons (n = 160) and inhibitory terminals (n = 282) showed Cav3.1-like immunoreactivity. Of the immunogold-PV-labeled processes, 46% of the axons and 23% of the terminals expressed Cav3.1-like immunoreactivity (Table 2). None of the asymmetrical, apparently excitatory terminals (n = 647) observed had Cav3.1 immunolabeling.

Table 2.

Colabeling of Cav3.1 and PV

| No. of labeled profiles (% dual labeled) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitory terminals | Axons | Shafts | Spines | Somata | Total | |

| Cav3.1 in peroxidase (% with PV) | 66 (24) | 42 (28) | 146 (17) | 41 (0) | 12 (25) | 307 (23) |

| PV in gold (% with Cav3.1) | 68 (23) | 26 (46) | 107 (37) | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | 204 (33) |

| Cav3.1 in gold (% with PV) | 62 (64) | 31 (53) | 158 (12) | 24 (0) | 50 (0.04) | 325 (22) |

| PV in peroxidase (% with Cav3.1) | 169 (23) | 133 (13) | 38 (50) | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | 343 (23) |

Ultrastructural distribution of observed profiles containing Cav3.1 and PV immunoreactivity. Each cell gives the total number of labeled profiles and in parentheses the percentage of these profiles that were double labeled by antibodies to both Cav3.1 and PV. For example, the cell in the upper left indicates that, with the Cav3.1 antibody labeled with peroxidase, 66 inhibitory nerve terminal profiles were found to be labeled, and that ∼24% of these (16) were also labeled with an immunogold-tagged PV antibody. The percentages pertain only to the given table cell and are not to be summed across cells.

As others have reported (Kovács et al., 2010; Parajuli et al., 2010), we find Cav3.1 immunolabeling predominantly on the cytoplasmic side of cell membranes. In the inhibitory terminals (n = 62) and axons (n = 31) containing immunogold-labeled Cav3.1, there was one Cav3.1 gold particle per 1.0 ± 0.47 μm length of axon. Within an axon having a visible terminal (n = 15), the mean distance between an axonal Cav3.1 immunogold particle and the closest terminal border was 444.9 ± 72.1 nm. Within terminals, 35.5% (44 of 124) of the Cav3.1 immunogold particles were located ≤50 nm from the closest plasma membrane, suggesting that these particles label T-type Ca2+ channels in the plasma membrane, with the remainder associated with internal structures (cf. Parajuli et al., 2010). Cav3.1 labeling was found 266.7 ± 21.7 nm from the active zone. Thus, as predicted by our hypothesis, Cav3.1 immunoreactivity is found in preterminal PV-labeled axons near, although not in, active zones.

Multifluorescence confocal immunohistochemistry

As a complementary approach, fluorescently labeled antibodies against Cav3.1, PV, a marker for neuronal axons (Tau1 protein), a presynaptic terminal marker (synaptophysin), and the nuclear marker, DAPI, to identify cell somata, were used. Typically, a given slice was stained with three antibodies plus DAPI, to ensure that axon terminals in CA1 s. pyramidale were proximate to pyramidal cell somata.

At 100× magnification, Cav3.1 labeling within single cells was diffuse and punctate, with individual puncta being rounded and between 250 and 600 nm in diameter (365 ± 9 nm; n = 100), often aggregated into variably sized “large puncta” that were found throughout pyramidal cell somata and primary dendrites, and sometimes at somatic edges or the nuclear membrane. Numerous puncta were also visible in spaces between neighboring somata, consistent with their localization on perisomatic-targeting axons. We evaluated 50 randomly selected axon segments labeled with Tau1, synaptophysin, and Cav3.1, within s. pyramidale (Fig. 4E,F; data in Table 2). The segments were ≥5 μm in length (10.5 ± 0.22 μm) and 500–700 nm in width. Most (29 of 50) contained large Cav3.1 puncta (1.2 ± 0.37 Cav3.1 puncta per 5 μm of axonal length), for a total of 79 Cav3.1 puncta, 20 of which (25%) were also coincident with synaptophysin labeling.

In slices immunolabeled for PV, Cav3.1, and synaptophysin, projections containing PV immunoreactivity that were ≥5 μm long (8.5 ± 0.86 μm; n = 50), 500–700 nm wide, and having synaptophysin immunoreactivity were analyzed. Two-thirds (34 of 50) of these axons contained large Cav3.1 puncta (total, 54 puncta; 1.0 ± 0.08 per 5 μm axon), of which 6 (11%) were also coincident with synaptophysin labeling. These data are consistent with the interpretation that the α3β4 nAChR-Cav3 mechanism is located on PV terminals. Thus, the immunohistochemical data supported predictions that Cav3.1 labeling is colocalized within presynaptic inhibitory interneuron profiles, appropriate for the proposed role of T-type Ca2+ channels in regulating GABA release.

Ca2+ stores and Ca2+-release coupling

T-type Ca2+ channel antagonists do not fully block nAChR-dependent GABA release (Fig. 3A), prompting the question of whether other factors might also be involved. Liberation of Ca2+ from endoplasmic reticulum stores triggers synaptic transmission at various synapses (Verkhratsky, 2005). To test the possibility that Ca2+-induced release from presynaptic Ca2+ stores (CICR) contributes to the ACh-evoked mIPSC burst, we bath-applied the Ca2+ pump inhibitor thapsigargin (TG) (10 μm) and observed that it reduced the mIPSC burst to 54.5 ± 3.8% (n = 5) of baseline (Fig. 5A,C). The responses were also reduced by another Ca2+ pump inhibitor, CPA (20 μm), to 48.4 ± 7.5% (n = 10); by ryanodine (Ryn) (100 μm) to 49.7 ± 4.3% (n = 7; Fig. 5B,C); and by caffeine (Caf) (10 mm) to 71.8 ± 4.8%, p > 0.05, n = 11 (Fig. 5C), but not by the IP3R blocker xestospongin C (XeC) (5 μm) to 97.1 ± 2.4%, n.s. (n = 5; Fig. 5C). These results suggest that ryanodine-receptor mediated CICR partially mediates the nAChR-induced GABA release, as is the case for nAChR-induced glutamate release in CA3 (Sharma and Vijayaraghavan, 2003). The onset delay of ACh-induced GABA release (Figs. 1B2, 3D), together with an apparent role for CICR, suggested that the relationship between Ca2+ sources and sensors for nAChR-induced GABA release might not reflect tight coupling between Ca2+ influx and transmitter release. The efficacy of Ca2+ chelators can be used to distinguish between tight and loose coupling between Ca2+ and its effectors (Neher, 1998; Bucurenciu et al., 2008). The membrane-permeant, slow Ca2+ chelator, EGTA-AM, disrupts loosely coupled asynchronous release (Hefft and Jonas, 2005; Daw et al., 2009; Karson et al., 2009), whereas synchronous release is resistant to EGTA-AM (Hefft and Jonas, 2005). We found that the nAChR-induced mIPSC burst was essentially abolished by EGTA-AM (Fig. 5D,F; to 9.1 ± 2.7% of baseline; p < 0.05; n = 3) but that action potential-dependent ACh-evoked release was not (Fig. 5E,F, red trace). This argues that nAChR-induced release is mediated by different mechanisms than action-potential dependent release and is consistent with the hypothesis that several steps may intervene between ACh action and GABA release.

Figure 5.

nAChR-mediated mIPSCs are dependent on store Ca2+ and are loosely coupled to Ca2+ increases. MLA (50 nm) was continuously applied in all experiments to isolate non-α7 nAChR-mediated responses. A, Depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores by thapsigargin (TG) (10 μm) (25 min; blue trace) reduced ACh-evoked mIPSC bursts compared with control (black trace). B, Blockade of RyRs by ryanodine (Ryn) (100 μm) (green trace) reduced ACh-evoked mIPSC bursts. C, Group data for Ca2+ store experiments. D, An ACh-evoked mIPSC burst was fully blocked by bath-applied EGTA-AM (100 μm for 10 min; red trace). E, ACh-induced responses in the absence of TTX were reduced, but not fully blocked, by EGTA-AM (red trace). The remaining IPSCs were blocked by DAMGO (1 μm) (blue trace). F, Summary of EGTA-AM effects on nAChR-mediated responses. Note that EGTA-AM abolished action potential-independent mIPSC bursts, but not action potential-dependent release, which was abolished by μOR activation. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ##p < 0.01 for EGTA-AM group.

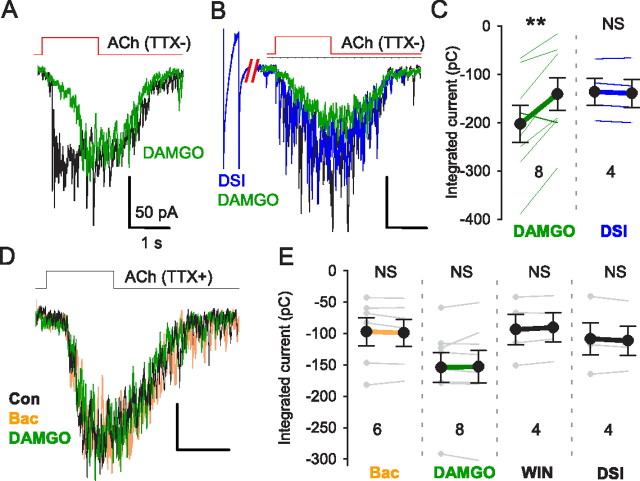

nAChR-induced mIPSC release is resistant to GPCR inhibition

HVA-controlled transmitter release is often modulated by presynaptic GPCRs (Wu and Saggau, 1997). T-type-Ca2+ channel-dependent release might be regulated differently. GABA release from perisomatic-targeting interneurons can be modulated by GABABRs, μORs, and CB1Rs (Freund, 2003; Freund and Katona, 2007). Activation of these receptors by synthetic agonists WIN 55212-2 (CB1Rs), DAMGO (μORs), baclofen (GABABRs), or endocannabinoid release from pyramidal cells via depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition (DSI) (Ohno-Shosaku et al., 2001; Wilson and Nicoll, 2001; Alger, 2002) profoundly inhibits normal action-potential-dependent transmission. When EGTA-AM had abolished ACh-evoked quantal release (50 nm MLA present), the remaining action potential-dependent IPSCs (Fig. 5E; 26.5 ± 3.1% of baseline; p < 0.05; n = 6) were almost totally eliminated by DAMGO (Fig. 5E,F; to 6.0 ± 1.4% of baseline; p < 0.01; n = 5). Indeed, in the absence of TTX, ACh-evoked responses were significantly reduced by DAMGO (to 64.3 ± 9.3% of baseline; p < 0.01; n = 8; Fig. 6A–C) but were unaffected by endocannabinoids elicited by a DSI protocol (Fig. 6B,C) (to 101.8 ± 1.7% of baseline; p > 0.05; n = 4). Surprisingly, however, when TTX was present, neither DAMGO, nor baclofen, nor cannabinoids (DSI or the synthetic CB1R agonist, WIN 55212-2) suppressed ACh-evoked mIPSC bursts (Fig. 6D,E; all p > 0.05), underscoring the differences between T-channel and HVA-mediated neurotransmitter release mechanisms.

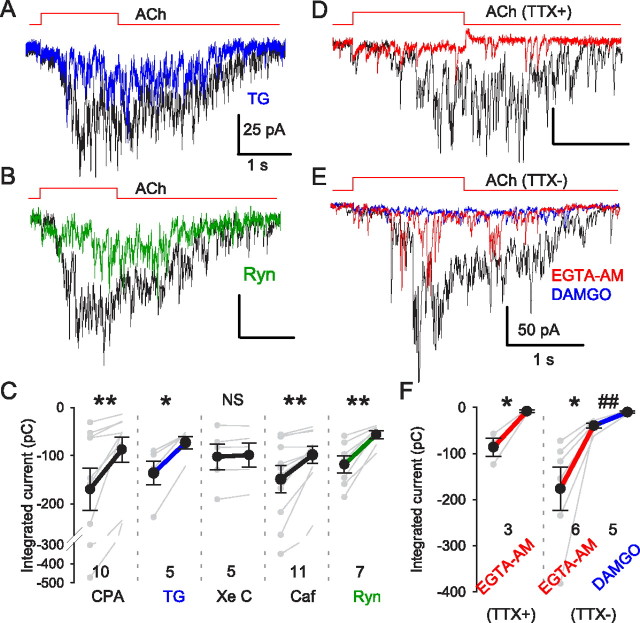

Figure 6.

nAChR-induced mIPSC bursts are resistant to GPCR inhibition. A, In the absence of TTX, DAMGO (1 μm) (green) reduced ACh-induced responses, showing that ACh-evoked action potential-dependent GABA release can be inhibited by μOR activation. B, Depolarization of postsynaptic pyramidal cells, which releases endocannabinoids and activates presynaptic CB1Rs, had no effect on the ACh-evoked response (blue). DAMGO still reduced the response (green trace). C, Group data from experiments as in A and B. D, In the presence of TTX, nAChR-induced mIPSC bursts are insensitive to baclofen (2 μm), DAMGO (1 μm), or WIN 55212-2 (2 μm), agonists of GABABRs, μORs, or CB1Rs, respectively. Releasing endocannabinoids by a DSI protocol (depolarizing PC to 0 mV for 5 s) also had no effect. E, Group data for experiments as in D. **p < 0.01.

Inhibition of action potential firing

If the α3β4 nAChR-T-channel-induced GABA release is functionally significant, it should alter the excitability of the postsynaptic cell. We therefore recorded from pyramidal cells in current-clamp mode (TTX absent, atropine present), inducing repetitive action potential firing with long depolarizing current pulses. The long current pulses were delivered every 45 s, and an ACh ejection was timed to end 0.5 s before the pyramidal cell was depolarized on alternate trials, so that an appropriate negative control action potential train could be compared with every experimental train. This prevented any slow changes in excitability from influencing the results. The ACh-induced burst of GABA release caused a relative hyperpolarization of the pyramidal cell membrane potential and delayed the onset of action potential firing (Fig. 7; mean delay of 1.5 ± 0.4 s; n = 5). Apart from this delay in firing, ACh did not alter pyramidal cell excitability—the relationship between action potential firing and time of occurrence was not changed (Fig. 7B). The inhibition of firing was abolished by gabazine (Fig. 7C; to 0.04 ± 0.04 s; p < 0.05; n = 4) or MLA plus mecamylamine (Fig. 7C; to 0.16 ± 0.05 s; p < 0.05; n = 5).

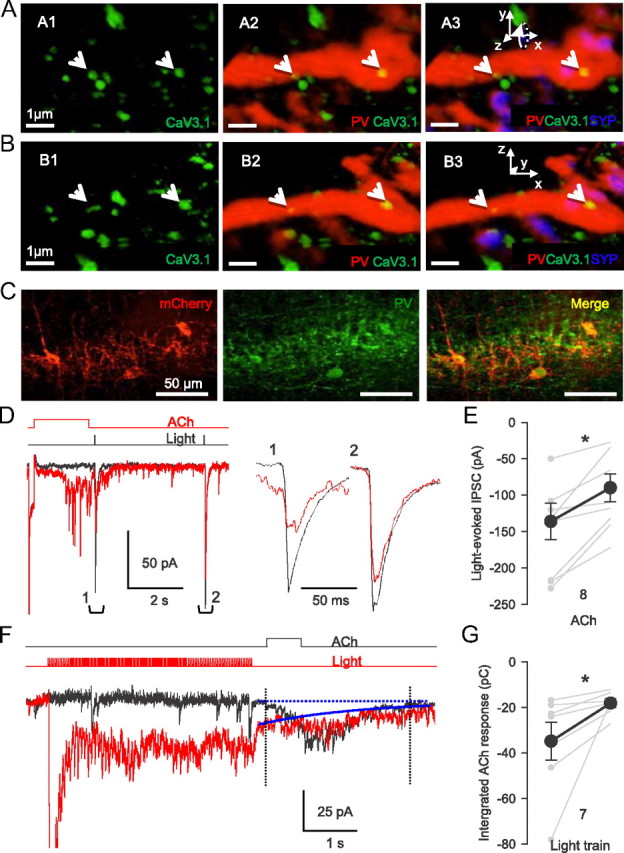

Identity of interneurons regulated by the α3β4 nAChR-T-channel mechanism

Different classes of perisomatic-targeting interneurons have different functional roles (Freund, 2003; Klausberger et al., 2005; Freund and Katona, 2007); hence it is important to identify the cells affected by the α3β4 nAChR-Cav3.1 mechanism. The lack of specific antibodies against α3β4 nAChRs precludes morphological determination of which terminals carry these receptors. Nevertheless, the marked segregation of inhibitory GPCRs to different perisomatic-targeting interneuron subtypes (Freund, 2003) allows for tentative operational identification. μORs are present on PV cells and absent from CCK cells (Drake and Milner, 2002; Freund and Katona, 2007). Conversely, CB1Rs are absent from PV cells, but densely present on CCK terminals (Wilson et al., 2001; Freund and Katona, 2007). The ability of DAMGO to abolish the early, action potential-dependent phase of ACh-induced bursts (compare Figs. 1A, 6A) indicates that focal ACh application affects PV cells, and suggests that the PV terminals are reasonable candidates for the site of α3β4 nAChRs. This inference is indirectly supported by the finding that Cav3.1 channels are located on PV axons near synaptic terminals (Fig. 8A,B); nevertheless, we do not have direct evidence that the action potential-dependent and action potential-independent stimulation of GABA release by α3β4 nAChRs originates from the same interneurons.

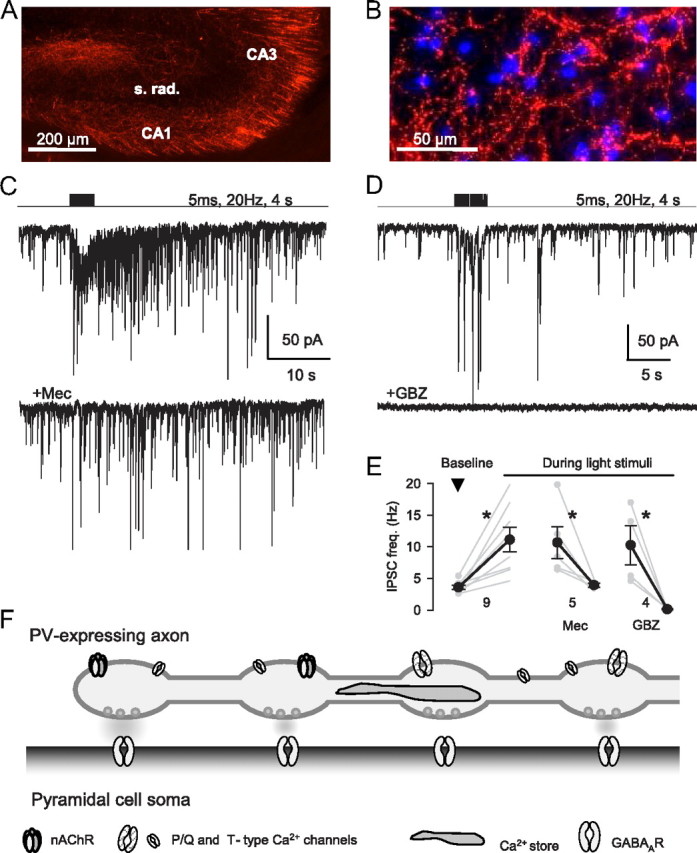

Figure 8.

Light stimulation of ChR2-expressing PV-expressing cells evokes GABA release from the same axons that are activated by focal ACh application. A, CaV3.1-immunoreactive puncta (green) are present on a PV (red) axon labeled with synaptophysin (blue) in CA1 stratum pyramidale. B, Same as A rotated into plane by 90°; see inset x–z coordinates. Cav3.1 puncta remained within the PV axon regardless of the angle of rotation, indicating that PV and Cav3.1 labeling are colocalized and not just in close apposition. Scale bars, 1 μm. C, Expression of ChR2-mCherry (red) in the CA1 region of PV-Cre mice. Sections were immunostained for PV (green) to confirm ChR2-mCherry expression in PV cells (merged image). D, Interaction between ACh-evoked and light-evoked, action potential-dependent GABA release. In control conditions, single light pulses elicited large IPSCs (black trace); IPSCs expanded at right. When preceded by an ACh pulse, the light-evoked IPSCs were reduced. Light-evoked IPSC measured from baseline just before the light to the IPSC peak. E, Group data for experiments as in B; *p < 0.05. F, The order of the applications was reversed from the experiment in D: ACh pulses induced bursts of IPSCs (black trace). When preceded by a 4 s train of blue light pulses (5 ms, 10 Hz), the integrated ACh-induced IPSC burst envelope was reduced. Bursts were integrated from dotted line in control, and from solid blue line after the light train. Both traces are averages of five trials. G, Group data for experiments as in F; *p < 0.05.

As a more direct test of the involvement of PV cells, we delivered a gene encoding the light-activated cation channel, channelrhodopsin2 (ChR2) (Zhang et al., 2010) selectively to PV interneurons. This was achieved by injecting a Cre-dependent AAV vector carrying ChR2 fused to the fluorescent marker protein mCherry (AAV-ChR2-mCherry) into hippocampi of PV-Cre mice. This resulted in intense expression of ChR2-mCherry in interneurons in or near s. pyramidale, and in apparent axonal processes surrounding pyramidal cell somata (Fig. 8C), which is consistent with labeling of PV-expressing perisomatic-targeting interneurons. Pulses of blue light (2–5 ms; ∼50 μm radius) delivered to these slices near the pyramidal cell in the absence of TTX elicits action potential-dependent IPSCs originating from PV interneurons (Fig. 8D, black trace). We then conducted “collision” experiments to determine whether the ACh-induced IPSCs arose from PV axons. ACh application to the terminal regions elicits axonal action potentials and TTX-sensitive IPSCs (Figs. 1A, 5E). The action potentials will propagate antidromically, encountering and annihilating spikes traveling orthodromically in the same axons. Thus, our hypothesis predicts that preceding a light flash by ACh application will reduce the light-evoked IPSCs originating from PV axons, because ACh-induced action potentials would be traveling in the same axons. Atropine, MLA, DHβE, and the GABABR antagonist CGP 54626 ([S-(R*,R*)]-[3-[[1-(3,4-dichlorophenyl) ethyl]amino]-2-hydroxypropyl](cyclohexylmethyl)phosphinic acid) (to preclude GABABR-dependent interaction between synapses) (Karson et al., 2009) were present for these experiments. The light-evoked IPSCs elicited 0.2 s after focal ACh induction of an IPSC burst were inhibited by 34% (from 136 ± 25 to 90 ± 17 pA; p < 0.05; n = 9; Fig. 8D, red trace; E). Conversely, repetitive light exposure (5 ms pulses; 10 Hz for 4 s) elicited a train of summated IPSCs (Fig. 8F, red trace) that reduced ACh-induced IPSCs (Fig. 8F, black trace) elicited 0.2 s later by 49% (from 35 ± 8 to 18 ± 2 pC; p < 0.05; Fig. 8G; n = 7), perhaps by transmitter depletion. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that the PV interneurons account for much of the GABA release resulting from activation of presynaptic α3β4 nAChRs.

Optogenetic stimulation of ACh release evokes nAChR-dependent IPSCs in pyramidal cells

Finally, our hypothesis predicts that selective stimulation of cholinergic fibers should induce nAChR-dependent GABA release. To test this prediction, we used the viral vector method to deliver ChR2 into cells of the medial septum/diagonal band of Broca, which project their axons extensively throughout the hippocampus (Mesulam et al., 1983). This resulted in transgene expression in cholinergic axons in the hippocampus (Fig. 9A,B). In the presence of NBQX, [(1S)-1-[[(7-bromo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-2,3-dioxo-5-quinoxalinyl)methyl]amino]ethyl]phosphonic acid hydrochloride (CGP 78608), and atropine, light stimulation of ChR2-labeled axons in acute hippocampal slices resulted in occasional transient occurrences of IPSCs, but the effects were too variable to permit extensive testing. To elicit robust and repeatable ACh-mediated responses, we added the cholinesterase inhibitor eserine (2 μm) to increase ACh actions (Pitler and Alger, 1992; Daw et al., 2009), together with a very low concentration (10–20 μm) of a K+ channel blocker, 4-AP, to enhance ACh release (Hull et al., 2009; Petreanu et al., 2009). Trains of blue light pulses (5 ms; radius, ∼100 μm; 10 or 20 Hz for 2–4 s) then evoked strong bursts of IPSCs in 9 of 16 pyramidal cells (baseline frequency, 3.6 ± 0.3 Hz, increased to 11.6 ± 1.9 Hz; p < 0.05; n = 9; Fig. 9C,E). The responses were eliminated by gabazine (10 μm; 0.14 ± 0.06 Hz; p < 0.05; n = 4; Fig. 9D,E) but were resistant to MLA (50 nm) and DHβE (10 μm), which were present in all experiments (Fig. 9C,D). Mecamylamine (10 μm) abolished the light-evoked IPSCs (to 3.9 ± 0.4 Hz; p > 0.05; n = 5; Fig. 9C,E). We confirmed that eserine had no significant effect on the α3β4 currents in IMR-32 cells (mean response, 82.9 ± 8.3%; n.s.; n = 6). Hence, selective stimulation of cholinergic fibers, independently of stimulation of other types of axons, glial cells, etc., that are unavoidably activated by electrical stimulation in the slice, can also activate non-α7 nAChRs on inhibitory interneurons and trigger GABA release.

Figure 9.

Endogenous ACh evokes nAChR-dependent GABA release. A, Expression of mCherry in cholinergic fibers in hippocampus 2 weeks after injection of AAV-mCherry virus into the medial septum/diagonal band of Broca of ChAT-Cre mice. B, Expression of ChR2-mCherry in cholinergic fibers in CA1 6 weeks after septal injection. DAPI staining (blue) shows cell nuclei. C, Stimulation of cholinergic fibers in a hippocampal slice by trains of blue light pulses evoked a barrage of IPSCs in a CA1 pyramidal cell (2 μm eserine, 10 μm NBQX, 5 μm CGP 78608, 20 μm 4-AP, 2 μm atropine, 50 nm MLA, and 10 μm DHβE present). The bottom trace shows light-evoked currents in the same cell is very much reduced by 10 μm mecamylamine. D, Different cell than in C. Light-evoked IPSCs are blocked by gabazine (10 μm). E, Group data of mean IPSC frequency in baseline (prestimulus) conditions and during train stimulation. *p < 0.05. F, Schematic model summarizing the conclusions of this report.

Figure 9F illustrates our model of how ACh may activate presynaptic α3β4 nAChRs and, together with axonal T-type Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ stores, induce GABA release.

Discussion

We find that axonal nAChRs and T-type Ca2+ channels in combination with CICR locally regulate synaptic inhibition. We infer that, by acting primarily on presynaptic α3β4 nAChRs, ACh depolarizes CA1 pyramidal cell perisomatic GABAergic axon terminals enough to open T-type Ca2+ channels. The resulting Ca2+ influx triggers CICR and GABA release that can transiently reduce pyramidal cell excitability. This mechanism has several key features, including operation at hyperpolarized membrane potentials, insensitivity to inhibition by presynaptic GPCRs, and independence from action potentials and HVA pathways. Generally, presynaptic neurotransmitter receptors either inhibit or amplify the action potential-initiated, HVA-dependent release process (Vizi and Lendvai, 1999). A notable exception is the highly Ca2+-permeable α7 nAChR, which, in combination with CICR, triggers significant transmitter release when present on nerve terminals (Sharma and Vijayaraghavan, 2003; Sharma et al., 2008). Other presynaptic non-α7 nAChRs operate in conjunction with HVAs (Léna and Changeux, 1997; Kulak et al., 2001) and modify the conventional release process. Our finding that activation of Cav3.1 T-type Ca2+ channels by presynaptic α3β4 nAChRs constitutes a novel GABA release mechanism.

The existence of α3β4 nAChRs near glutamatergic, but not GABAergic, terminals has been proposed (Alkondon and Albuquerque, 2002; Kawa, 2007; Liu et al., 2007; Albuquerque et al., 2009) on the basis of TTX-insensitive transmitter release induced by globally applied nicotinic agonists. In some experiments, α3β4 nAChRs elicited only action potential-dependent IPSCs (Alkondon and Albuquerque, 2002; Zhu et al., 2005), suggesting that ACh activated distant axonal or somatodendritic receptors. Lack of a specific antibody for α3β4 nAChRs prevents a precise determination of their localization. The small radius of action of focal microiontophoresis (Fig. 1C,D) showed that the α3β4 nAChRs and T-type Ca2+ channels are reasonably close to GABAergic synapses. While ∼50% of the α3β4 nAChR-induced GABA release is Cd2+ sensitive, the rest is not, suggesting that increases in [Ca2+]i triggered directly or indirectly by α3β4 nAChRs could be significant (Fig. 2) (cf. Kawa, 2007). The net influence of different Ca2+ sources on transmitter release will depend on the location of channels, terminal geometry, etc. (Bucurenciu et al., 2008, 2010).

T-type Ca2+ channels differ markedly from HVA channels. They are largely unaffected by GPCR-dependent regulatory mechanisms that alter HVA function (Lambert et al., 2006) (but cf. Bender et al., 2010). They open in response to small depolarizations from the resting potential, so they are well adapted to sense modest, local stimulation, such as the nonsynaptic actions of neurotransmitters like ACh that can act by volume conduction (Vizi and Lendvai, 1999). Ordinarily, the contribution of T-type Ca2+ channels to GABA release in hippocampus is overwhelmed by rapid and massive Ca2+ influx through HVA channels during action potential-initiated transmission (Hefft and Jonas, 2005). With local ACh stimulation, the occurrence of multiple, brief nAChR openings could transiently but repeatedly activate T-type Ca2+ channels without inactivating them. Importantly, opening of only a few HVA channels is sufficient for GABA release from PV cells (Bucurenciu et al., 2010). Thus, in conjunction with Ca2+ provided by CICR, T-type Ca2+ channels could increase enough [Ca2+] within the tiny axon terminals to trigger release. Colocalization of T-type Ca2+ channels and nAChRs may thus extend the dynamic range of synaptic communication to stimuli that are below action potential threshold. A cooperative arrangement of α3β4 nAChRs and T-type Ca2+ channels may be particularly advantageous because α3β4 nAChRs are subject to strong inward rectification caused by intracellular polyamines (Haghighi and Cooper, 2000). The decrease in α3β4 nAChR conductance with strong depolarizations will prevent outward current from shunting the slower and smaller T-type Ca2+ channel-mediated depolarization and, hence, could be especially significant in facilitating transmitter release initiated by these channels. A very recent paper describes finding Cav3.2 T-type Ca2+ channel at the active zones of certain cortical glutamatergic synapses where they regulate glutamate release in conjunction with HCN1 channels (Huang et al., 2011). In that system, nAChRs were not involved and T-type Ca2+ channels were not found on inhibitory cells. It will be interesting to learn how general the association between T-type Ca2+ channels and release is, and whether the resistance to regulation by presynaptic GPCRs that we report is a universal property of release processes governed by these channels. The existence of two systems for transmitter release could allow for switching between different regulatory modes occurs as circumstances vary.

Neurotransmitter release mediated by T-type Ca2+ channels has a delayed onset and persistent time course when compared with HVA-mediated release. Persistent, action potential-induced, asynchronous GABA release (Hefft and Jonas, 2005; Daw et al., 2009; Karson et al., 2009) is suited to integrating signals over longer durations than is possible with fast synaptic transmission. Asynchronous release processes reflect loose coupling between Ca2+ influx and the release mechanism (Hefft and Jonas, 2005), and may involve a distinct Ca2+ sensor (Sun et al., 2007). In our experiments, bath application of EGTA-AM revealed loose coupling between T-type Ca2+ channels and GABA release. T-type Ca2+ channels could conceivably contribute to asynchronous transmission in other cases as well.

T-type Ca2+ channels are involved in nonaxonal neurotransmitter release. In leech cardiac neurons, they exist throughout the neuritic tree and control graded postsynaptic responses (Ivanov and Calabrese, 2000). T-type Ca2+ channels mediate hormone release from neuroendocrine cells (Carbone et al., 2006), GABA release at reciprocal dendrodendritic synapses in the olfactory bulb (Egger et al., 2003, 2005), and release from retinal bipolar cells (Pan et al., 2001). In some spinal neurons, Ni2+ and mibefradil reduce spontaneous mEPSCs without affecting evoked EPSCs (Bao et al., 1998), suggesting that T-type Ca2+ channels might be involved, although these agents also inhibit R-type Ca2+ channels (Catterall et al., 2005). We found that the selective T-type Ca2+ channel antagonist, TTA-P2 (Dreyfus et al., 2010), also antagonized ACh-induced GABA release, which strengthened the case for these channels in conventional release.

We used Cav3.1 labeling in combination with immunofluorescent markers for axons (Tau1 protein), presynaptic terminals (synaptophysin), and specific interneurons (PV) to identify Cav3.1 on hippocampal interneuron terminals. Pharmacological evidence pointed to the involvement of Cav3.1 or 3.3 channels, rather than Cav3.2, which are blocked by low concentrations of Ni2+ (IC50 = 12 μm) (Catterall et al., 2005). Cav3.3 channels are only found in the adult striatum (McRory et al., 2001), whereas Cav3.1 is ubiquitous. Interneurons within s. pyramidale express Cav3 channels on their somatodendritic regions, and there is heavy staining for these channels in CA1 s. pyramidale, amid a dense mesh of basket cell axons (McKay et al., 2006). Cav3.1 was not detected on axon terminals, but a low density of T-type Ca2+ channels on inhibitory axons might have been below the resolution of the methods used (McKay et al., 2006). Recently T-type (and R-type) Ca2+ channels were found on the axon initial segments (AISs), although not axon terminals, of cells in the cochlear nucleus (Bender and Trussell, 2009; Bender et al., 2010). T-type Ca2+ channels on the AISs affect the generation of axonal complex spikes, and thereby strongly influence synaptic output. With TTX present, the T-type Ca2+ channel-initiated Ca2+ influx in cochlear nucleus cells remained confined to the AIS, suggesting that T-type Ca2+ channels at the AIS have different functions than those near axon terminals.

Perisomatic-targeting PV interneurons include both axoaxonic cells that narrowly innervate pyramidal cell axon initial segments, and basket cells having a wider range of somatodendritic synaptic contacts and different functional roles (Freund and Katona, 2007; Klausberger and Somogyi, 2008). We could not distinguish between axoaxonic and basket cells, and doing so will be an important future task. We focused on PV-expressing interneurons, and our data do not exclude a role for T-type Ca2+ channels on CCK-expressing or other interneurons in CA1. Indeed, Cav3.1 was detected on some non-PV-labeled profiles, but testing other candidates went beyond the scope of this investigation. Although we observed that PV cell α3β4 nAChRs were significant effectors of the ACh actions on GABA release, we did observe a component that was attributable to α7 nAChRs, which are expressed on CCK− basket cells (Freund, 2003), and this avenue remains to be explored.

Because the nAChR-Cav3.1 mechanism does not require action potential firing, it is not expected to engage the wide dispersion of GABAergic inhibition triggered by somatic action potentials. Normally, however, stimulation of the local (terminal and preterminal) nAChRs (Fig. 1) may trigger action potentials that could propagate laterally throughout the axonal network. T-type Ca2+ channels participate in the generation of thalamocortical rhythms (Huguenard and Prince, 1992; Huguenard and McCormick, 2007) and the oscillations associated with absence epileptic seizures (Huguenard, 2002) and antagonists of these channels are used therapeutically in these seizure disorders. By reducing the nicotinic activation of GABA inhibition in the hippocampus, such treatments could have ancillary effects on epileptiform activity and even nicotine use as well. The high incidence of tobacco use among schizophrenics is often interpreted as an attempt at “self-medication” by the individuals (D'Souza and Markou, 2011). If schizophrenia involves deficits in perisomatic, PV cell-mediated inhibition (Lewis et al., 2005), then it may be significant that the mechanism that we have discovered would increase GABA release from these cells, perhaps partially compensating for the deficit.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH Grants R01 MH077277 and R01 DA014625 (B.E.A.), and R01 MH53631 and R01 GM48677 (J.M.M.). Plasmids pAAV-EF1a-double floxed-hChR2 (H134R)-mCherry-WPRE-HGHpA and pAAV-EF1a-double floxed-mCherry-WPRE-HGHpA were obtained from the plasmid-sharing site Addgene, through a material transfer agreement with Dr. K. Deisseroth (Stanford University, Stanford, CA). Antibody 9303 was provided by CURE Digestive Diseases Research Center, Antibody/RIA Core, NIH Grant KD41301. We thank Prof. T. Snutch for advice on the use of the Cav3x antibodies. We are indebted to Drs. Jimok Kim and Scott Thompson for their valuable comments on a draft of this manuscript.

V.N.U. and J.J.R. are employees of Merck and Co., Inc. (USA), and potentially own stock and/or stock options in the company.

References

- Albuquerque EX, Pereira EF, Alkondon M, Rogers SW. Mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:73–120. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alger BE. Retrograde signaling in the regulation of synaptic transmission: focus on endocannabinoids. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;68:247–286. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M, Albuquerque EX. A non-alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor modulates excitatory input to hippocampal CA1 interneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:1651–1654. doi: 10.1152/jn.00708.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atasoy D, Aponte Y, Su HH, Sternson SM. A FLEX switch targets channelrhodopsin-2 to multiple cell types for imaging and long-range circuit mapping. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7025–7030. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1954-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine GJ, Santamaria F, Tanaka K. Local calcium signaling in neurons. Neuron. 2003;40:331–346. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00639-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao J, Li JJ, Perl ER. Differences in Ca2+ channels governing generation of miniature and evoked excitatory synaptic currents in spinal laminae I and II. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8740–8750. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08740.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartos M, Vida I, Jonas P. Synaptic mechanisms of synchronized gamma oscillations in inhibitory interneuron networks. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:45–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender KJ, Trussell LO. Axon initial segment Ca2+ channels influence action potential generation and timing. Neuron. 2009;61:259–271. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender KJ, Ford CP, Trussell LO. Dopaminergic modulation of axon initial segment calcium channels regulates action potential initiation. Neuron. 2010;68:500–511. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder LI, Frankfurter A, Rebhun LI. The distribution of tau in the mammalian central nervous system. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:1371–1378. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.4.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucurenciu I, Kulik A, Schwaller B, Frotscher M, Jonas P. Nanodomain coupling between Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ sensors promotes fast and efficient transmitter release at a cortical GABAergic synapse. Neuron. 2008;57:536–545. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucurenciu I, Bischofberger J, Jonas P. A small number of open Ca2+ channels trigger transmitter release at a central GABAergic synapse. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:19–21. doi: 10.1038/nn.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone E, Giancippoli A, Marcantoni A, Guido D, Carabelli V. A new role for T-type channels in fast “low-threshold” exocytosis. Cell Calcium. 2006;40:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA, Perez-Reyes E, Snutch TP, Striessnig J. International Union of Pharmacology. XLVIII. Nomenclature and structure-function relationships of voltage-gated calcium channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:411–425. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celio MR, Baier W, Schärer L, de Viragh PA, Gerday C. Monoclonal antibodies directed against the calcium binding protein parvalbumin. Cell Calcium. 1988;9:81–86. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(88)90027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Sharp AH, Hata K, Yunker AM, Polo-Parada L, Landmesser LT, McEnery MW. Site-directed antibodies to low-voltage-activated calcium channel Cav3.3 (ALPHA1I) subunit also target neural cell adhesion molecule-180. Neuroscience. 2007;145:981–996. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cueni L, Canepari M, Adelman JP, Lüthi A. Ca2+ signaling by T-type Ca2+ channels in neurons. Pflugers Arch. 2009;457:1161–1172. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0582-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daw MI, Tricoire L, Erdelyi F, Szabo G, McBain CJ. Asynchronous transmitter release from cholecystokinin-containing inhibitory interneurons is widespread and target-cell independent. J Neurosci. 2009;29:11112–11122. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5760-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly-Roberts DL, Arneric SP, Sullivan JP. Functional modulation of human “ganglionic-like” neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) by L-type calcium channel antagonists. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;213:657–662. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake CT, Milner TA. Mu opioid receptors are in discrete hippocampal interneuron subpopulations. Hippocampus. 2002;12:119–136. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]