Abstract

Uveal melanoma (UM) is the most prevalent intraocular malignant tumor in the Western world. The prognosis of survival in the presence of metastatic disease is 2-7 months, depending on the treatment applied.

This article presents a case of metastatic UM with successful complex treatment of liver metastases.

A 49-year old female, underwent removal of the right eyeball in 1996 due to a histologically confirmed uveal melanoma. After 11 years, CT revealed a mass in the left kidney and multiple metastases in the liver. After left nephrectomy, 6 chemotherapy courses with dacarbazine were performed. The increasing liver metastases were observed. Additional 4 intraarterial (i/a) chemotherapy courses were administered using cisplatin, doxorubicin, fluorouracil, and interferon alfa. After few courses increase in CTC Grade 4 liver transaminases was seen. A partial response was observed, and in December 2008 the patient underwent surgery removing all liver metastases by 7 wedge or atypical resections. All margins were tumor-free. 21 months after liver resections and 14 years since diagnosis, the patient is alive without evidence of disease.

Successful treatment of metastatic uveal melanoma was due to a timely application of a combination of several treatment methods and good prognostic factors of the patient.

Keywords: uveal melanoma, liver metastases, intraarterial chemotherapy, liver resection

Introduction

Uveal melanoma (UM) is the most prevalent intraocular malignant tumor in the Western world. Most frequently it develops in the choroid (80%) and the ciliary body (15%). The incidence of uveal melanoma in the Western countries is 7 new cases per 1 million of population annually [1]. Five, ten and fifteen year survival is 65%, 52%, 'and 46% respectively [2-5]. COMs (Collaborative Ocular Melanoma study Group) indicates that the incidence of metastases within 5 years is 25%, and patient mortality within 2 years in the presence of a metastatic disease is 92% [6,7]. Most frequently (about 60-80% of cases), uveal melanoma metastasizes into the liver due to the biologicalanatomical peculiarities (hematogenous dissemination, subsequent homing of cancer cells or their preferential survival in the liver and other factors) [2-4]. other common sites of metastasis are lungs and bones [6].

The etiology of uveal melanoma is not entirely clear. The disease is most commonly diagnosed in people with light eyes that are under prolonged exposure to UV-radiation. Other possible etiological factors are fair skin and oculodermal melanocytosis [1,8,9]. Nowadays, some UM-related genetic changes have been identified, most frequently as chromosomal aberrations on chromosomes 1, 3, and 8. Monosomy 3, gain of 8q, combination of loss of 1p36, and monosomy 3 are identified as factors that have a detrimental effect on survival [1].

Unfortunately, efforts to reduce mortality from metastatic UM have not been very successful during the last decades. The prognosis of survival in the presence of metastatic disease is 2-7 months, depending on the treatment methods [1]. 1-year overall survival (OS) is 13-29% [10,11]. The most common negative prognostic factors are age (over 60 years), male sex, short interval between primary diagnosis and manifestation of first metastases, and multiple liver metastases [10,12-14]. Metastatic UM requires complex therapy. Most frequently treatment includes systemic chemotherapy (dacarbazine, fotemustine, immunotherapy, etc.) [6]. Detection of isolated liver metastases complicates the treatment and requires surgery, chemoembolization or i/a chemotherapy to ensure maximum destruction of neoplastic lesions.

According to the data of the Lithuanian Canter Registry (Institute of oncology, Vilnius University), 269 new cases of skin melanoma were registered in 2009, while the number of cases of UM is unknown.

In this article we would like to present a case of metastatic UM with successful complex treatment of liver metastases.

Case Report

A 49-year old female patient, underwent removal of the right eyeball (enucleation bulbi) in 1996 for a histologically confirmed uveal (choroid) melanoma. No additional treatment was applied. Eleven years later (11/2007), computer tomography (CT) revealed a mass in the left kidney and multiple metastases in liver, involvingg both liver lobes. After initial interdisciplinary consensus, a left nephrectomy was performed (reaching an R0 situation), while systemic chemotherapy should treat the liver metastases. Initial surgery was notadministered due to size and multiple spread of the metastases. Histological examination confirmed the metastastic disease of the uveal melanoma. Afterwards, 6 cycles of dacarbazine were administered (1000 mg/m2 1 day infusion every 3 weeks). An increase of liver metastases (in size and in number) was seen under this treatment.

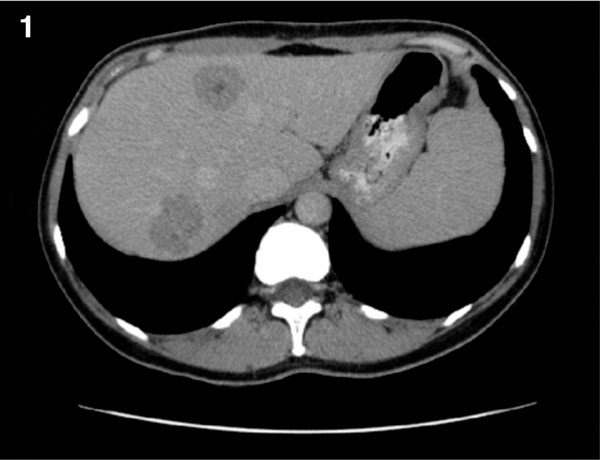

Body CT performed in June 2008 showed multiple (about 10) metastatic lesions in both lobes, 11-26 × 38 mm in size; no other metastases were detected (Figure 1). During June-october 2008, the patient underwent 4 courses of intraarterial (i/a) chemotherapy (scheme: cisplatin 100 mg/m2 day 1; doxorubicin 40 mg/m2 day 1; fluorouracyl 500 mg/m2 days 1-3; interferon alfa 4 MU/m2 days 1-3 with a 40-50 days interval). After first and fourth course, an increase of liver transaminases was observed (according to CTC criteria - Grade 4), and thus chemotherapy on the third day was discontinued. After fourth course of i/a chemotherapy, thrombocytopenia (CTC Grade 4) was observed, requiring afereted thrombocyte transfusion (1 dose). other side effects (CTC Grade 1-2) included nausea, vomiting, and fever, but required no additional treatment.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT image of the liver shows multiple unresectable liver metastases.

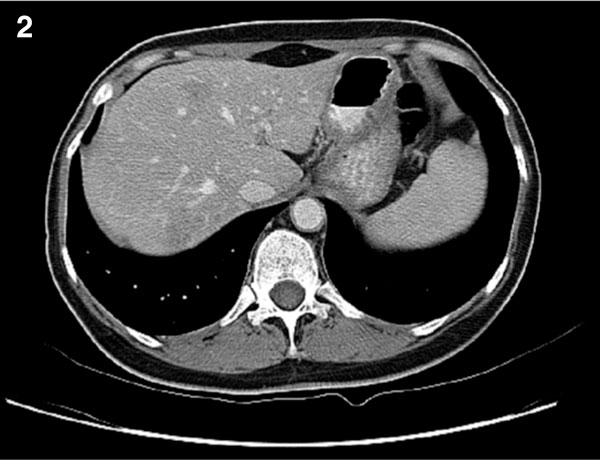

In November 2008, abdominal CT revealed partial response in the liver (Figure 2) metastasis according to RECIST criteria. Therefore, interdisciplinary consensus suggested surgical exploration and metastasectomy.

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced CT image of the liver shows partial response after four courses of iintraarterial chemotherapy.

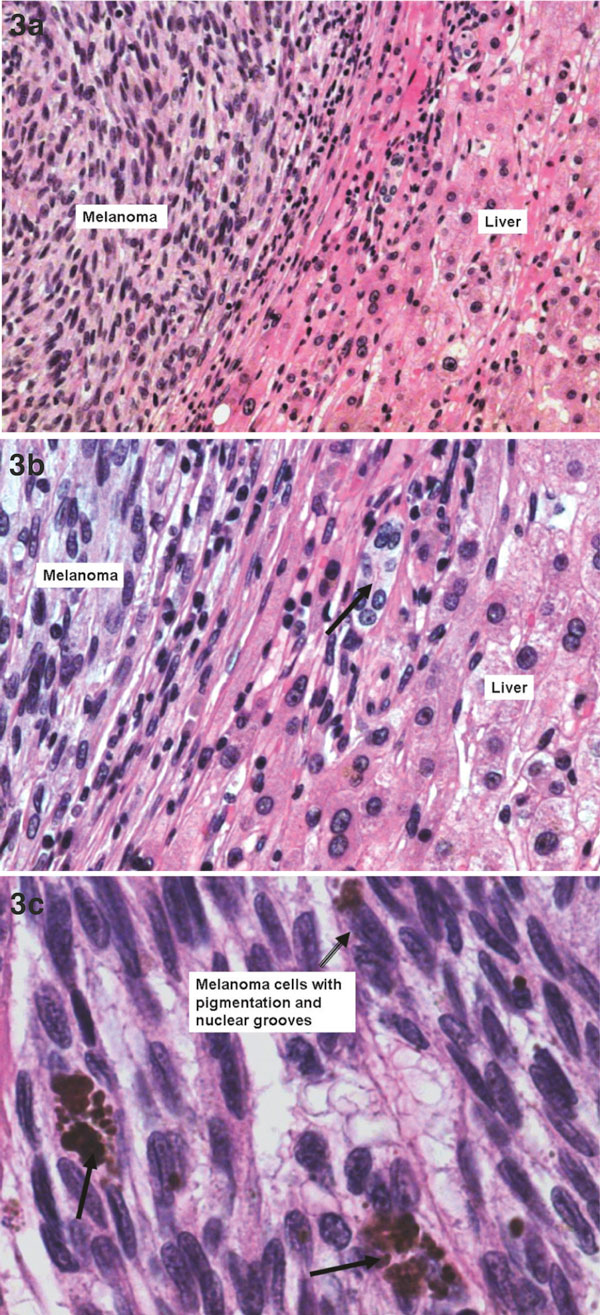

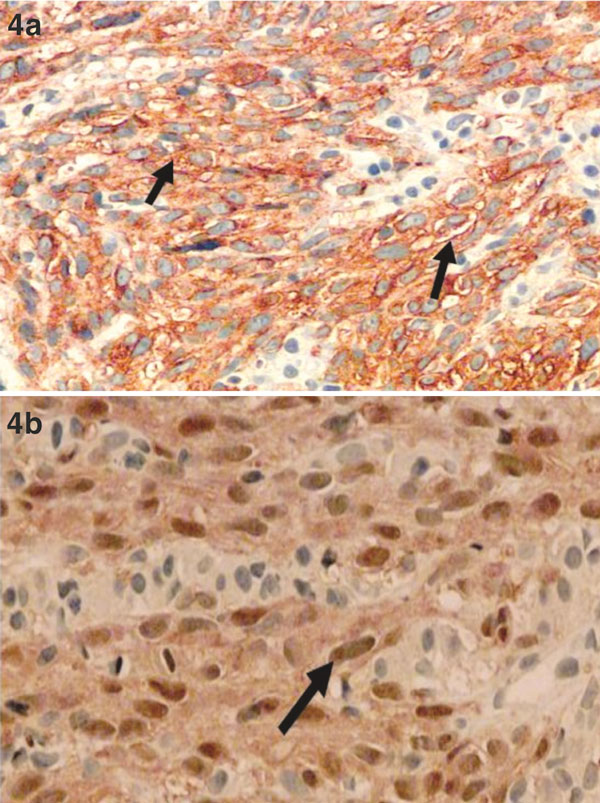

In December 2008 the patient underwent liver resection with the removal of all 7 lesions from liver. All resections were performed as wedge or atypical resections, operative blood loss was 500 ml. Histology confirmed 5 from 7 nodules as metastases of initial uveal melanoma (Figures 3, 4), all resected with clear margins (2 from 7 near the resection border). The post-operative period was uneventful, the patient could be discharged on post-operative day 8. Follow-up CT scans in september 2009 and september 2010 revealed physiological postoperative changes in the liver without detection of further metastases (Figure 5). At present, at 21 month after the removal of liver metastases, the patient is free of signs of recurrence. The patient's condition is excellent without complaints; liver function and its markers are within the physiological range.

Figure 3.

(a) Melanoma metastasis in liver tissue: epithelioid and spindled cell type melanoma cells on the left and across the fibrous septa on the right -- normal liver cell plates. HE × 100. (b) Melanoma metastasis in liver tissue: epithelioid and spindled cell type melanoma cells on the left and across the fibrous septa liver cell plates one could see a bile duct in the middle of the slide (black arrow). HE × 200. (c) Melanoma cells with nuclear grooves and pigmentation, melanophages (black arrows). HE × 400.

Figure 4.

(a) Melanoma cells are positive for HMB45 and S100 immunohistochemistry stains: membranous and cytoplasmic for HMB45 and (b) nucleus and cytoplasmic for S100 (blackarrow). HE × 200.

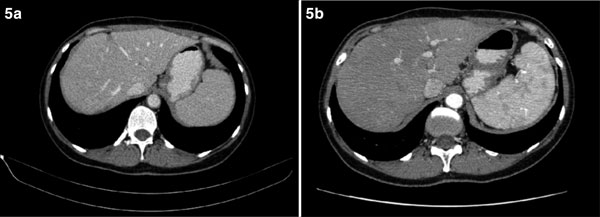

Figure 5.

(a) Contrast-enhanced CT image of the liver 9 and (b) 21 month after resection of the liver metastases shows only postsurgical lesions.

Discussion

We presented a patient with complex treatment for metastatic uveal melanoma. Following the diagnosis of metastasis in the kidney, a nephrectomy was performed, while liver resections of the metastases were not recommended, though initially discussed. The patient underwent systemic chemotherapy, but it proved to be ineffective. subsequent i/a chemotherapy (chemotherapeutic agents with interferon) yielded partial response, and the patient was interdisciplinary discussed as a candidate for definite surgery and successfully operated.

The choice of our treatment tactics was determined by isolated liver metastases and good functional status of the patient. The patient's prognostic factors played a significant role in the choice of treatment tactics and the prognosis. The patient's prognostic factors were good: age below 60 years (35 years at the time of diagnosis), female sex, long period until the presence of first metastases (11 years), and isolated metastases in the liver. It is noteworthy that the patient also had negative prognostic factors multiple liver metastases which resulted initially in the decision of not to perform the liver metastasectomy right away. It is noteworthy though, that changes in the clinical results, stable disease as well as progressive disease and regression, in metastatic patients should always be again presented and discussed interdisciplinarily, since further therapeutic options may always be discussed in an individual setting.

Scientific publications most frequently define the following negative prognostic factors for uveal melanoma: ciliary body involvement detected on histological examination, and up to 10 liver metastases [12,15]. other authors revealed that up to 4-5 liver metastases without signs of micrometastases, and radically performed resection of the liver metastases may result in a better prognosis for metastatic disease [3,6]. A French study investigated 3873 patients with uveal melanoma, in whom 798 patients developed liver metastases [3]. Furthermore, it was noted that time to diagnosis of liver metastases (less than 24 months after primary diagnosis), non-radical resection of liver metastases (R1-2), more than four liver metastases, and confirmed milliary metastases all are negatively associated with overall survival [3]. Therefore, a close follow-up in all uveal melanoma patients is recommended in order to detect possible metastases at the earliest possible time. This enables a possible surgical resection as well as possible systemic treatment aiming at complete regression. The same study recommends prevention in patients with diagnosed extensive uveal melanoma. This is liver MRI, which is especially recommended in patients who after eyeball enucleation are diagnosed with monosomy 3 (FIsH Fluorescent in situ hybridization) [3,16,17]. We do not do genetic test for uveal melanoma patients in Lithuania routinely.

When analyzing therapeutic techniques selected in our patient, it is important to note the importance of the removal of liver metastasis. The benefit of the resection of liver metastases has been confirmed by a number of clinical studies. The following factors determine the applicability of liver metastasis resection: the patient's good functional condition, absence of the signs of disease dissemination, and anatomical size of the tumor - 30-40% of liver parenchyma [12]. L. Kodjikian et al. analyzed 602 patients and indicated that the most effective treatment techniques were radical resection of liver metastases and intraarterial chemotherapy (with fotemustine or cisplatin), partial resection of the metastases with intraarterial chemotherapy is less effective, but the poorest results were obtained when administering best supportive care [12]. The experience of the Institut Curie (France) confirms these results: in cases of R0 liver metastasis resection, median survival (Ms) was 27 months, compared to the overall post-operative MS of 14 months [3]. According to other authors, median overall survival was 25 months in R0 liver metastasis resection, 16 months in R2 resection, and 11 months in systemic chemotherapy or best supportive care [15]. In our case, the patient underwent the removal of all liver metastases visible on CT. At present, at 21 months after the removal of liver metastases, the patient is free of signs of recurrence. The relevant point in the analysis of the treatment options of UM liver metastases is that surgery is important in case of secondary liver metastases as well. In such cases one can also combine liver resection, chemoembolization, isolated liver perfusion, etc. [10]. There have also been vaccines tested following the resection of primary liver metastases to delay secondary metastases [10,18].

Due to anatomical peculiarities, when metastases are located only in liver, and when immediate R0 liver surgery is impossible, i/a chemotherapy, chemoembolization, or a combination of both can be applied. Due to size and multiple metastases in various liver segments as well as in the kidney, initial surgery was not chosen initially, but it was possible later. For this reason, nephrectomy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy were scheduled, followed by i/a chemotherapy (a combination of platinum-based chemotherapy agents and interferon) [19]. The patient did not tolerate i/a chemotherapy very well, as shown by severe increase in liver transaminases and severe thrombocytopenia. Literature provides extensive descriptions of direct in-trahepatic administration of chemotherapeutic agents as adjuvant therapy to surgery. Frequently the treatment is initiated with surgical removal of metastases [12,15], while in our patient the surgical approach was performed after i/a chemotherapy reducing the metastatic lesions (in size and number) and reevaluation of the patient.

Chemoembolization or i/a chemotherapy are effective techniques for the treatment of liver metastases since usually liver metastases are hypervascular. The reported response rate to chemoembolization is 36%, though no survival benefit compared to systemic chemotherapy is reported [15,20]. Agents most frequently used in chemoembolization and i/a chemotherapy are dacarbazine, cisplatin, fotemustine, or their combinations [12,15,21,22]. In our case, the patient underwent 6 courses of systemic chemotherapy with dacarbazine alone and therefore we selected a combination of several platinum-based agents for i/a chemotherapy.

The patient survived 14 years after initial diagnosis and 21 months since removal of liver metastases. Literature indicates that median overall survival in metastatic uveal melanoma is 14-15 months when applying a combination of surgery with or without i/a chemotherapy, and 11 months if surgery is contraindicated and chemotherapy alone is applied [3,15]. Median survival in metastatic uveal melanoma patients treated by applying HAI (hepatic arterial infusion) of cisplatin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine was 16 months [21]. When patients underwent transcatheter chemoembolization (TACE) of liver metastases with cisplatin, median time to progression is 8.5 months [22]; when applying TACE with fotemustine or cisplatin, median OS is 6 months. Currently, administration of i/a fortemustine as an adjuvant therapy in high-risk UM patients is being analyzed [23]. There is an ongoing EORTC (18021) clinical trial comparing the efficiency of i/a fotemustine vs systemic fotemustine [3]. Further studies are being conducted on the efficacy of the combinations of older chemotherapeutic agents (dacarbazine) with temozolomide, gemcitabine aiid thalidomide [2,24-26].

In our patient, successful results of metastatic uveal melanoma management were due to a timely application of a combination of several treatment methods and good prognostic factors of the patient. Though initial evaluation ruled out surgical removal of the liver metastases, reevaluation after several chemotherapeutical strategies lead to the surgical approach of resection. Therefore, reevaluation of patients with malignancies, even with systemic disease, should be performed in order to gain the best possible survival outcome for the individual patient.

References

- Bosch T, Kilic E, Paridaens D, Klein A. Genetics of Uveal Melanoma and Cutaneous Melanoma: Two of a Kind? Dermatology Research and Practice. 2010;71:7–19. doi: 10.1155/2010/360136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakalian S, Marshall JC, Logan P, Faingold D, Maloney S. et al. Molecular Pathways Mediating Liver Metastasis in Patients wiht Uveal Melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(9):951–956. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariani P, Piperno-Neumann S, Servois V, Berry MG, Dorval T, Plancher C. et al. Surgical management of liver metastases from uveal melanoma: 16 years experience at the Institut Curie. EJSO. 2009;35(9):1192–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietschel P, Panageas KS, Hanlon C, Patel A, Abramson DH, Chapman PB. Variates of survival in metastatic uveal melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8076–8080. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.6534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen OA. Malignant melanomas of the human uvea: 25-year follow-up of cases in Denmark, 1943-1952. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1982;60:161–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1982.tb08371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel S, Nir I, Hendler K, Lotem M, Eid A, Jurim O, Pe'er J. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009. pp. 1042–1046. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Diener-West M, Reynolds SM, Agugliaro DJ. et al. Development of metastatic disease after enrollment in the COMS trials for treatment of choroidal melanoma: Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group Report No 26. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(9):1639–1643. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.12.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Pokrzywniak A, Jöckel K-H, Bornfeld N, Sauerwein W, Stang A. Positive interaction between light iris color and ultraviolet radiation in relation to the risk of uveal melaoma: a case-control study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(2):340–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AD, De Potter P, Fijal BA, Shields CL, Shields JA, Elston RC. Lifetime prevalence of uveal melanoma in white patients with oculo(dermal) melanocytosis. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(1):195–198. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)92205-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama T, Mastrangelo MJ, Berd D, Nathan FE, Shields CL, Shields JA, Rosato EL, Rosato FE, Sato T. Protracted survival after resection of metastatic uveal melanoma. Cancer. 2000;89:1561–1568. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001001)89:7<1561::AID-CNCR21>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gragoudas ES, Egan KM, Seddon JM, Glynn RJ, Walsh SM, Finn SM. et al. Survival of patients with metastases from uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(9):383–390. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32285-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodjikian L, Grange JD, Baldo S, Baillif S, Garweg JG, Rivoire M. Prognostic factors of liver metastases from uveal melanoma. Graefe's Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;243:985–993. doi: 10.1007/s00417-005-1188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskelin S, Pyrhönen S, Hahka-Kemppinen M, Tuomaala S, Kivelä T. A prognostic model and staging for metastatic uveal melanoma. Cancer. 2003;97(2):465–475. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kath R, Hayungs J, Bornfeld N, Sauerwein W, Höffken K, Seeber S. Prognosis and treatment of disseminated uveal melanoma. Cancer. 1993;72(7):2219–2223. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931001)72:7<2219::AID-CNCR2820720725>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivoire M, Kodjikian L, Baldo S, Kaemmerlen P, Négrier S, Grange JD. Treatment of liver metastases from uveal melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12(6):422–428. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins L, Levy-Gabriel C, Lumbroso-Lerouic L, Sastre X, Dendale R, Couturier J, Piperno-Neumann S, Dorval T, Mariani P, Salmon R, Plancher C, Asselain B. Prognostic factors for malignant uveal melanoma. Retrospective study on 2241 patients and recent contribution of monosomy-3 research. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2006;29(7):741–749. doi: 10.1016/S0181-5512(06)73843-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onken MD, Worley LA, Ehlers JP, Harbour JW. Gene expression profiling in uveal melanoma reveals two molecular classes and predicts metastatic death. Cancer Res. 2004;64(20):7205–7209. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berd D, Maguire HC Jr, Schuchter LM, Hamilton R, Hauck WW, Sato T. et al. Autologous hapten-modified melanoma vaccine as postsurgical adjuvant treatment after resection of nodal metastases. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(9):2359–2370. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meric F, Patt YZ, Curley SA, Chase J, Roh MS, Vauthey JN, Ellis LM. Surgery after downstaging of unresectable hepatic tumors with intra-arterial chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7(7):490–495. doi: 10.1007/s10434-000-0490-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedikian AY, Legha SS, Mavligit G, Carrasco CH, Khorana S, Plager C, Papadopoulos N, Benjamin RS. Treatment of uveal melanoma metastatic to the liver: a review of the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience and prognostic factors. Cancer. 1995;76(9):1665–1670. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951101)76:9<1665::AID-CNCR2820760925>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melichar B, Voboril Z, Lojfk M, Krajina A. Liver metastases from uveal melanoma: clinical experience of hepatic arterial infusion of cisplatin, vinblastine and dacarbazine. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56(93):1157–1162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppert PE, Fierlbeck G, Pereira P, Schanz S, Duda SH, Wietholtz H, Rozeik C, Claussen CD. Transarterial chemoembolization of liver metastases in patients with uveal melanoma. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74(33):38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelter V, Schalenbourg A, Pampallona S, Peters S, Halkic N, Denys A, Goitein G, Zografos L, Leyvraz S. Adjuvant intraarterial hepatic fotemustine for higj-risk uveal melanoma patients. Melanoma Res. 2008;18(3):220–224. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32830317de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittel A, Schuster R, Bechrakis NE. et al. A twocohort phase II clinical trial of gemcitabine plus treosulfan in patients with metastatic uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res. [2005;15:447–451. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200510000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solti M, Berd D, Mastrangelo MJ, Sato T. A pilot study of low-dose thalidomide and interferon α-2b in patients with metastatic melanoma who failed prior treatment. Melanoma Res. 2007;17:225–231. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32823ed0d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedikian AY, Papadopoulos N, Plager C, Eton O, Ring S. Phase II evaluation of temozolomide in metastatic choroidal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2003;13:303–306. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200306000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]