SUMMARY

Background

Chronic use of NSAIDs is associated with GI toxicity that increases with age.

Aims

The GI safety and therapeutic efficacy of Ibuprofen chemically associated with phosphatidylcholine (PC) was evaluated in osteoarthritic (OA) patients.

Methods

A randomized, double-blind trial of 125 patients was performed. A dose of 2400 mg/day of ibuprofen or an equivalent dose of Ibuprofen-PC was administered for 6 weeks. GI safety was assessed by endoscopy. Efficacy was assessed by scores of analgesia and anti-inflammatory activity. Bioavailability of ibuprofen was pharmacokinetically assessed.

Results

Ibuprofen-PC and ibuprofen provided similar bioavailability/therapeutic efficacy. In the evaluable subjects a trend for improved GI safety in the Ibuprofen-PC group compared with ibuprofen was observed, that did not reach statistical significance. However, in patients >55 years of age, a statistically significant advantage for Ibuprofen-PC treatment vs ibuprofen in the prevention of NSAID-induced gut injury was observed with increases in both mean Lanza scores and the risk of developing > 2 erosions or an ulcer. Ibuprofen-PC was well tolerated with no major adverse events observed.

Conclusions

Ibuprofen-PC is an effective osteoarthritic agent with an improved GI safety profile compared to ibuprofen in older OA patients, who are most susceptible to NSAID-induced gastroduodenal injury.

Keywords: NSAID, ulcer, analgesia, ibuprofen, endoscopy, phosphatidylcholine

INTRODUCTION

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) are extensively used to treat patients with osteoarthritis. Chronic high dose use of NSAIDs is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. NSAID-induced GI toxicity has been estimated to annually result in approximately 107,000 hospitalisations and 16,500 deaths in the US alone (1). The prevalence of NSAID-induced gastroduodenal injury has been estimated to be 20–40% in chronic users with the predominant damage (>85%) occurring in the stomach. Approximately 2% of these patients with endoscopic ulcers may present with serious clinically relevant gastroduodenal ulcers and hemorrhage (2). With greater than 100 million NSAID prescriptions in 2004 in the US alone, the risk of NSAID-induced GI toxicity risk remains a serious issue (3).

The choice and use of NSAIDs and gastroprotective agents have been driven by effective pain and inflammation relief in the context of risk factors. Among various risk factors, age is an important driver of NSAID intolerance (2). Age (> 60 yrs) is associated with 5 times greater risk for NSAID-induced GI injury than observed in an age matched population, not chronically consuming NSAIDs (4). More recently, Hippisley-Cox et al (5) have confirmed that all NSAIDs, including COX-2 (cyclooxygenase-2) selective agents (coxibs), have an increased risk of GI toxicity that increases with age. Many osteoarthritic patients have multiple risk factors, making them more susceptible to NSAID-induced peptic ulcer disease over all compared to the general population. Therefore, there is a great unmet need for efficacious NSAIDs that can safely be used in OA patients, especially those of increased age, which as discussed previously, is an independent risk factor for NSAID-induced peptic ulcer disease (2, 5).

Various approaches have been used to decrease the risk of NSAID-induced GI toxicity such as the use of coxibs, and the combined use of traditional NSAIDs and gastroprotective or anti-secretory agents such as misoprostol or proton pump inhibitors (6–9). The recent withdrawal of multiple coxibs, due to concerns about their cardiovascular toxicity (10–11), demonstrates the need for additional NSAIDs with reduced GI toxicity.

Surface injury to the gastric mucosa also renders the tissue abnormally permeable to back-diffusion of luminal acid as originally described by Davenport for aspirin (12). NSAIDs have been demonstrated to disrupt the gastric mucosal barrier by a COX independent pathway that rapidly compromises the acid resistive properties of the tissue (13). As will be discussed in more detail later, we have obtained compelling pre-clinical evidence (14–16) and positive data from a short-term pilot clinical trial in healthy subjects (17) that pre-association of NSAIDs with phosphatidylcholine (PC) can protect the GI mucosa from the injurious action of ibuprofen and related NSAIDs. These observations served as the basis for the current clinical trial.

Ibuprofen-PC is an oil emulsion of ibuprofen and soy-derived PC that has been softgel encapsulated. In the present work, a Phase II trial was designed to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy and GI safety of Ibuprofen-PC versus ibuprofen at therapeutic doses to treat osteoarthritis. In a randomized, multi-centre, blinded clinical trial, equivalent doses of active ibuprofen (prescription Motrin®) and Ibuprofen-PC formulations were compared. The primary endpoint of this study was to compare the incidence and severity of Motrin® and Ibuprofen-PC induced endoscopically observable gastroduodenal erosions/ulcers using the Lanza scoring method (18). Secondary endpoints of the study were to assess and compare: the analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity of treatments using Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritic Criteria (WOMAC™) and a Visual Analog Scale (VAS); the bioavailability of ibuprofen by pharmacokinetic analyses; and the overall safety of the treatments based on physical examination, laboratory tests and the incidence rates of adverse events.

METHODS

Drugs

Ibuprofen-PC formulation in softgel encapsulated oil suspension was provided by PLx Pharma Inc., Houston, TX. The proprietary formulation contained 1:1 w/w of ibuprofen acid (BASF Corp., Mt. Olive, NJ) and Phosal 35SB (American Lecithin, Oxford, CT) together with small amounts of compendial excipients as required by the manufacturer (Cardinal Health, Somerset, NJ) for softgel encapsulation. Phosal 35SB contains ~35% w/w phosphatidylcholine (PC).

Subjects and Scoring

One hundred and twenty-five osteoarthritis patients requiring anti-inflammatory agents (age range 18–83) with minimal or no baseline evidence of damage to the gastric and duodenal mucosa as observed under baseline endoscopy were enrolled at six centres, whose respective Institution Review Boards had previously approved the outlined protocol. Informed Consent was obtained from each subject at enrollment. Endoscopic damage was assessed by using the Combined Lanza Endoscopic Scoring System prior to and after a 6 week course of 2400 mg/day of Motrin® or 2400 mg/day of active ibuprofen in Ibuprofen-PC. Lanza Score is a categorical score (0–4) of endoscopic upper GI erosions, ulcers and mucosal hemorrhage defined as follows: Score 0 = normal stomach and proximal duodenum; 1 = Mucosal hemorrhages only; 2 = one or two erosions; 3 = three to ten erosions; 4 = greater than ten erosions or an ulcer (18). Erosions were defined as flat white-based mucosal breaks of any size, and ulcers were defined as mucosal breaks of 3 mm or more demonstrating unequivocal depth. Minimal damage was defined as Lanza Score of 2 or less. Patients with mucosal damage of Grades 0, 1 and 2 were eligible for enrollment in the study.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Patients ≥ 18 years of age who had osteoarthritis of the knee and/or hip requiring NSAID therapy were included in the study. Subjects were excluded from the study if they had previous ulcer disease, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease within the prior 6 months, a baseline Lanza Score of >2, use of NSAIDs within 2 weeks of enrollment, use of MAO inhibitors or any pain medication other than over-the-counter (OTC) acetaminophen (paracetamol), the use of gastroprotective agents (including proton pump inhibitors and H2-receptor antagonists) within 3 days, or any other significant concomitant health problem other than osteoarthritis, notably GI problems including ulcers, frequent indigestion or heartburn (within the past 6 months). Females of child-bearing age unwilling to use adequate contraception for the duration of the study and pregnant or nursing females were not eligible. Patients with a hyper-sensitivity to lecithin, aspirin, ibuprofen or any other NSAID were also excluded from the study.

Study Design

The study objectives were to evaluate the GI safety, overall safety and efficacy of Ibuprofen-PC versus ibuprofen. The primary safety endpoint was change in gastroduodenal Lanza Scores over baseline within treatment groups. Other safety endpoints were: incidence of endoscopic gastroduodenal ulcers (with and without symptoms); adverse events; and changes in various clinical and laboratory assessments. The primary efficacy endpoint was change from baseline in the WOMAC subscale scores within the treatment groups. Other efficacy analyses included differences in the WOMAC scores between treatment groups and changes from baseline in the patients’ VAS assessments and the bioavailability of ibuprofen using several key pharmacokinetic parameters.

Patients with informed consent were randomized to treatment with prescription Motrin® or Ibuprofen-PC, 800 mg of active ingredient three times a day (2400 mg of ibuprofen/day). At pre-enrollment, all patients underwent a physical exam, laboratory evaluation of haematology, blood chemistry and, if relevant, a pregnancy test. The medical history and use of any concomitant medications were collected. Endoscopies were performed at baseline and after 6 weeks. Every two weeks on protocol, patients were evaluated for pain and inflammation using the WOMAC and VAS scores and, to monitor compliance, pill counts were assessed. Adverse events and the use of concomitant medications were monitored throughout the study.

Endoscopy

Baseline endoscopy was performed no more than 7 days before initiating the study medication and the findings were compared with the endoscopic score after 6 weeks on treatment. All endoscopists were blinded to the treatment group. To minimize subjective interpretation, all endoscopic images were also scored by a blinded central assessor (Frank L. Lanza, MD). Any conflicts were resolved through an adjudication process to determine a consensus score. A change of Lanza score of >2 over baseline was considered clinically significant. Using this criterion, patients would have to develop a Lanza score of 2 (1 or 2 erosions) if their gastroduodenal mucosa showed no evidence of injury, Lanza score of 0 (no erosions and/or no mucosal hemorrhages) at baseline; or alternatively developed 10 or more erosions and/or an ulcer if they had the maximal allowable Lanza score of 2 (1 or 2 erosions) at baseline.

Pain and Inflammation Assessment

The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis (WOMAC) Index is an extensively validated, self-administered questionnaire that is widely used to assess osteoarthritis-related disability of the knee or hip. The WOMAC assessment was performed on Day 0, and at follow-up visits on Weeks 2, 4, and 6.

To evaluate the relative change in pain and inflammation relief over baseline, Patient Global Assessment using a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was measured. Patients were asked to evaluate his/her overall assessment of treatment efficacy by making a mark on a visual analog scale. The scale ranged from “Great Worsening” on one end of the scale to “Great Improvement” on the other. The VAS assessment was performed at follow-up visits on Week 2, Week 4 and Week 6.

Bioavailability

On day 0 (baseline) and Week 4, patients were administered their randomised study treatment and blood samples were drawn at the following time points: 0 (pre-dose), 45, 60, 75, 90 and 120 minutes. Sera were prepared, coded and sent to MedTox Labs (St. Paul, MN) for ibuprofen analysis by HPLC.

Adverse Events

Drug-related adverse events were categorised into unlikely, possible, probable or definitely treatment related based on investigator decision using version 3.0 of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events of the National Institutes of Health (http://ctep.info.nih.gov). Patients were encouraged to report adverse events spontaneously or in response to general non-directed questioning. An adverse event was diagnosed as a symptomatic ulcer only if a clinically relevant ulcer (mucosal lesion > 3mm in diameter with depth) was observed under endoscopy at the 6 week time point and the patient complained of epigastric pain consistent with a diagnosis of having a peptic ulcer.

Statistical Analysis

In this study, three analysis populations were utilized: Intent to Treat (ITT), Evaluable for Efficacy and Evaluable for Gastrointestinal (GI) Toxicity. All patients who received at least one treatment were included in the ITT population. Inclusion in the two evaluable groups was dependent on study compliance (which was based upon the subjects’ following the pre-set requirement of both taking the test medication as directed and not taking prohibited medications).

The primary efficacy analysis consisted of the individual subscales of the WOMAC (pain, physical function, joint stiffness) and the total score compared with the findings at baseline. For each subscale and the total score, the percentage change from baseline was calculated by subtracting the score at each follow-up visit from the score at baseline, dividing by the baseline score and multiplying by 100.

For testing within each treatment group separately, the paired t-test was used to compare the percentage change from baseline in WOMAC scores at each follow-up visit. For secondary efficacy analyses, a manner similar to that used for the primary efficacy analyses was employed to investigate differences in the WOMAC between treatment groups. Differences between treatment groups were analysed using the t-test to determine if the percentage change from baseline in the WOMAC scores at each follow-up visit was significantly different between the two treatment groups.

For the VAS assessment, within each treatment group separately, a paired t-test was used to determine if the patient’s VAS assessment of treatment efficacy was statistically significantly different than zero. Differences between treatment groups were analyzed using the t-test to determine if the assessment of efficacy was significantly different between the two treatment groups.

All 125 patients were included in the analyses of adverse events and the changes in laboratory assessments, physical exams and vital signs. Analysis of Lanza scores was performed by calculating the raw change from baseline at Week 6. The data designated as the change in gastric or duodenal lesion score refers to the most severely affected area within a subject. The Lanza data failed to be normally distributed, thus non-parametric statistics were utilized. Within each treatment group separately, a signed-rank test was used to determine if the patient’s Lanza score was statistically significantly different at Week 6 compared to Day 0 (baseline). Differences between treatment groups were analysed using the rank-sum test to determine if the assessment of safety was significantly different between the two treatment groups.

Subgroup Analysis

Age is a known risk factor in NSAID-induced GI toxicity. Prognostic factor testing using ANOVA methods revealed a borderline statistically significant interaction between patient age and treatment in relation to the change in Lanza score (p-value = 0.0726, ANOVA). Upon determination that age and treatment had a significant interaction, two population cohorts of ≤55 and > 55 population were defined using the median age of the ITT population. Each cohort was independently evaluated for efficacy, pharmacokinetics, Lanza Score and adverse events.

RESULTS

Patient Disposition/Demographics

Patients were required to have a history of osteoarthritis requiring non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents. A total of 125 patients were enrolled in the study, and 108 patients completed the study. The demographics of the ITT population is detailed in Table 1. No significant difference in the ITT population based on age, gender, BMI, race or other factors listed in Table 1 was observed. The evaluable population for GI safety had similar demographics to the ITT population, the details of which have not been provided in the table for the sake of brevity. The reasons for study drop-out in the ibuprofen group (7/64) were as follows: 4–withdrew consent; 1–adverse event unrelated to treatment; 2–lost to follow-up. The reasons for drop-out in the Ibuprofen-PC group (10/61) were as follows: 4–withdrew consent; 1–adverse events unrelated to treatment; 3–non-compliant; 2–other (1–lost to follow-up, 1–withdrew due to diarrhoea, based upon the subject’s and not the investigator’s discretion). The drop-out rates between treatment groups were not statistically different. None of the patients were excluded from the Evaluable for GI toxicity population for having a high baseline Lanza score. The reasons for the exclusion from the Evaluable for GI toxicity population were limited to: lost to follow-up; refusal to perform the 6-week endoscopy; and failure to remain compliant with the study drug.

Table 1.

Subject Demographics by Treatment Group and Age

| Population | Overall | 55 and Under | Over 55 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Ibuprofen (n=64) | Ibuprofen-PC (n=61) | Ibuprofen (n=33) | Ibuprofen-PC (n=31) | Ibuprofen (n=31) | Ibuprofen-PC (n=30) | |

| Mean ± STD or N (%) | Mean ± STD or N (%) | Mean ± STD or N (%) | Mean ± STD or N (%) | Mean ± STD or N (%) | Mean ± STD or N (%) | |

| Intent to Treat | ||||||

| Mean Age (years) | 54.1 ± 12.6 | 54.2 ± 13.5 | 44.5 ± 9.0 | 44.1 ±10.2 | 64.3 ± 6.1 | 64.8 ± 6.7 |

| Age Range (years) | 27–74 | 18–83 | 27.0–55.0 | 18.0–55.0 | 56.0–74.0 | 56.0–83.0 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 27 (42.2) | 26 (42.6) | 13 (39.4) | 14 (45.2) | 14 (45.2) | 12 (40.0) |

| Female | 37 (57.8) | 35 (57.4) | 20 (60.6) | 17 (54.8) | 17 (54.8) | 18 (60.0) |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 27 (42.2) | 33 (54.1) | 10 (30.3) | 13 (41.9) | 17 (54.8) | 20 (66.7) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 26 (40.6) | 21 (34.4) | 14 (42.4) | 13 (41.9) | 12 (38.7) | 8 (26.7) |

| Black | 11 (17.2) | 6 (9.8) | 9 (27.3) | 4 (12.9) | 2 (6.5) | 2 (6.7) |

| Native Hawaiian or Islander | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| BMI at First Dose (kg/m2) | 31.2 ± 6.9 | 30.6 ± 6.9 | 32.8 ± 7.6 | 32.3 ± 7.7 | 29.5 ± 5.7 | 28.8 ± 5.7 |

| Reason for Termination | ||||||

| Completed Study | 57 (89.1) | 51 (83.6) | 31 (93.9) | 24 (77.4) | 26 (89.3) | 27 (90.0) |

| Subject Withdrawal | 4 (6.2) | 4 (6.6) | 1 (3.0) | 3 (9.7) | 3 (9.7) | 1 (3.3) |

| Unrelated Adverse Event | 1 (1.6) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Non-compliance | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.3) |

| Other | 2 (3.1) | 2 (3.3) | 1 (3.0) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.3) |

| Evaluable for GI Toxicity | (n=58) | (n=49) | (n=30) | (n=23) | (n=28) | (n=26) |

| Mean Age (years) | 54.1 ± 12.6 | 54.6 ± 13.6 | 44.6 ± 9.1 | 43.7 ± 11.1 | 64.3 ± 5.9 | 64.3 ± 6.0 |

Endoscopic Results

In the total evaluable population for GI toxicity, the mean as well as the percentage of patients that developed multiple gastroduodenal lesions or a lesion score of >2 in the ibuprofen and Ibuprofen-PC groups were not significantly different (Tables 2 and 3). The primary pre-planned analysis did not find a statistically significant difference in the increase in Lanza scores over baseline between the two treatment groups in the total evaluable population (mean ± SD were 1.6 ± 1.4 in the ibuprofen group vs 1.3 ± 1.4 in the Ibuprofen-PC group, p = 0.24). Although not statistically different, this trend favors the experimental treatment group. This trend justified further subgroup analysis of the data, which was performed on a post-hoc basis.

Table 2.

Mean and Median Change in Gastric or Duodenal Lesion Scoreα

| N | Mean Age ± STD | Age Range | Mean Change ± STD | Median Change | Rank Sum p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Evaluable | ||||||

| Ibuprofen | 58 | 54.1 ± 12.6 | 27–74 | 1.6 ± 1.4 | 2 | |

| Ibuprofen-PC | 49 | 54.6 ± 13.6 | 18–79 | 1.3 ± 1.4 | 1 | |

| Ibuprofen | ||||||

| 55 and Under | 30 | 44.6 ± 9.1 | 27–55 | 1.2 ± 1.4 | 1 | |

| Over 55 | 28 | 64.3 ± 5.9 | 56–74 | 2.0 ± 1.4 | 2 | 0.0353* |

| Ibuprofen-PC | ||||||

| 55 and Under | 23 | 43.7 ± 11.1 | 18–55 | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 1 | |

| Over 55 | 26 | 64.3 ± 6.0 | 56–79 | 1.2 ± 1.4 | 1 | 0.7643 |

Statistically significant (p-value <0.05) vs OA patients using the same study medication < 55 years of age;

the total evaluable population described here and the subsequent figures represents the Intention To Treat (ITT) population minus the drop-outs.

Table 3.

Percentage of Patients with a Change in Gastric or Duodenal Lesion Score of >2

| Change N (%) | <2 Change N (%) | >2 Fisher’s Exact Test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Evaluable | |||

| Ibuprofen | 40 (69.0) | 18 (31.0) | 0.2713 |

| Ibuprofen-PC | 39 (79.6) | 10 (20.4) | |

| 55 and under cohort | |||

| Ibuprofen | 24 (80.0) | 6 (20.0) | 0.5217 |

| Ibuprofen-PC | 16 (69.6) | 7 (30.4) | |

| Over 55 cohort | |||

| Ibuprofen | 16 (57.1) | 12 (42.9) | 0.0148* |

| Ibuprofen-PC | 23 (88.5) | 3 (11.5) | |

Statistically significant (p-value <0.05) comparing Ibuprofen vs Ibuprofen-PC in evaluable OA subjects > 55 years of age;

the total evaluable population described here represents the Intention To Treat (ITT) population minus the drop-outs.

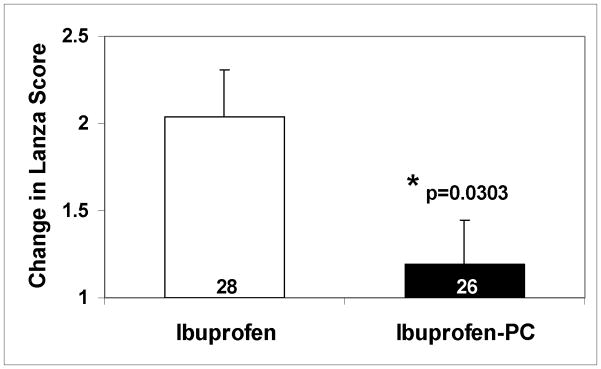

OA patients >55 years of age

Age is a known risk factor for NSAID-induced GI toxicity (19–20). To determine the effect of age on the change in Lanza Score, a prognostic factor analysis was performed. Using ANOVA methods, a borderline statistically significant interaction between treatment and age as a categorical variable was observed, split into two groups at the median age of 55, relative to changes in Lanza Scores (p-value = 0.0726, ANOVA). Using this criterion, two subsets (≤ 55 and >55 years of age) were analysed. The mean change in Lanza Score in patients older than the median age (55 years of age) was analyzed as a subset; a statistically significant advantage for Ibuprofen-PC treatment in the prevention of NSAID-induced gut injury was observed as depicted in Figure 1A. The results of the effect of age and the mean and median change in Lanza Score in the various subsets are summarized in Tables 2 & 3. The mean change in gastroduodenal lesion score in ibuprofen-treated subjects was significantly higher in the >55years group than in the ≤55 years group (Table 2, p-value = 0.0353, Rank-Sum). In contrast, no such age-dependent increase in gastroduodenal lesion score was discernible in OA patients treated with Ibuprofen-PC (p = 0.76, Rank-Sum).

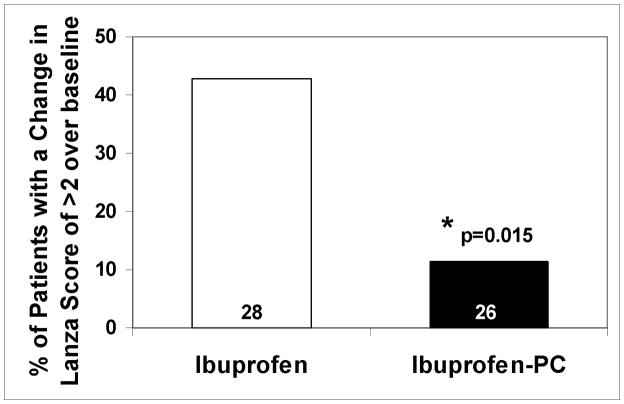

Figure 1.

Graphic depiction of the endoscopic findings in the clinically-relevant subgroup of OA patients >55 years of age. Ibuprofen at a dose of 2400 mg/day was associated with a statistically significant difference in: (A) the increase (mean ± SEM) in mean Lanza score over baseline; (B) the increase in the percentage of patients with multiple gastroduodenal erosions/ulcers (change in Lanza scores >2) in comparison with OA patients of comparable age taking an equivalent (NSAID) dose of Ibuprofen-PC over the 6-week study period. These results demonstrate that older OA patients taking ibuprofen were 3.7 times more likely to develop multiple gastroduodenal erosions/ulcers than those taking an equivalent (anti-arthritis) dose of Ibuprofen-PC.

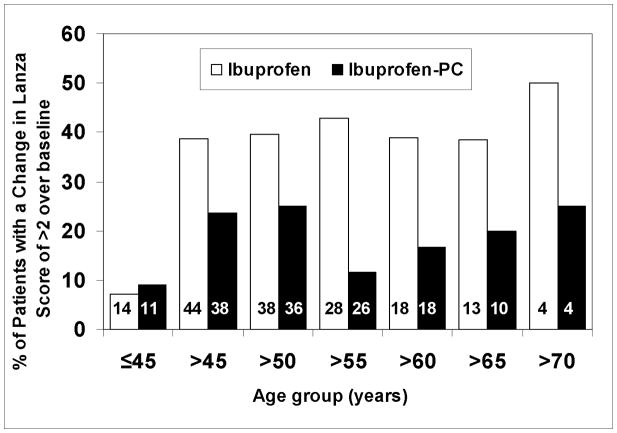

Within the ibuprofen-treated patients (Table 3), the relative risk of multiple gastroduodenal erosions, with an increase in Lanza score >2, in the cohort of patients >55 years was 2.15 times more likely (or a 114.5% increased risk) than patients ≤55 years, and is consistent with reports in the literature that with increasing age more gastroduodenal damage is observed with chronic NSAID exposure (2). Interestingly, within the Ibuprofen-PC treated patients (Table 3), the cohort of patients >55 had a risk ratio of 0.38 or a 62.0% decreased risk of developing multiple gastroduodenal erosions than patients ≤55 years. As depicted in Figure 1B, the percentage of patients who developed gastroduodenal lesion score of >2 was 42.9% and 11.5% in the ibuprofen and Ibuprofen-PC groups, respectively, in the >55 age cohort and were statistically significantly different (p-value = 0.0148, Fisher’s Exact). In this subset of patients over the age of 55 years, ibuprofen treated patients were 3.7 times more likely (or a 270% increased risk) to develop multiple gastroduodenal erosions than the Ibuprofen-PC treated patients in the cohort. This cohort had a mean age of 64 and was similar in all relevant demographics listed in Table 1. We have also compared the change in Lanza score of >2 using other age cut-offs, as depicted in Figure 2. This data supports the case that Ibuprofen consistently caused a greater percentage of subjects to sustain more severe gastroduodenal injury (Lanza score >2) than those treated with Ibuprofen-PC, in accordance to this endoscopic criterion in the age groups older than 45 years of age. Collectively, these data indicate that Ibuprofen-PC reduced the age-related increase in NSAID-induced gastroduodenal lesions.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the percentage of patients in the two treatment groups with multiple gastroduodenal erosions/ulcers (change in Lanza scores >2) using different age cut-offs. It can be appreciated that Ibuprofen consistently caused a greater percentage of subjects to sustain more severe gastroduodenal injury (Lanza score >2) than those treated with Ibuprofen-PC in subjects older than 45 years of age.

Additionally, one or more endoscopic ulcers were observed in 17/125 (13.6%) of the ITT population, with 12/64 in the ibuprofen-treated group (18.8%) and only 5/61 (8.2%) in the Ibuprofen-PC group at the study end. Ulcer symptoms were recorded in 4/12 subjects in the ibuprofen group (33%) with an endoscopic ulcer vs 1/5 (20%) subjects in the Ibuprofen-PC group with one or more endoscopic ulcers. The number of patients with an endoscopic ulcer without symptoms was 8/64 (12.5%) in the ibuprofen group and 4/61 (6.6%) in the Ibuprofen-PC group. These differences in ulcer incidence, however, did not reach statistical significance, presumably due to the small size of this pilot trial. Unlike the Lanza scores outlined above, no age-dependent increase in ulcer incidence (with or without symptoms) was observed in either treatment population.

Treatment-Related Adverse Events Other than GI Erosions/Ulcers

The percentage of first occurrence of adverse events (other than gastroduodenal erosions and ulcers) that were possibly, probably or definitely treatment related is summarized in Table 4. Only two serious adverse events were reported in the trial; both patients were in the Ibuprofen-PC group (2/61, 3.3%). These serious adverse events were considered unrelated to study treatment by the investigators. One serious adverse event was fracture of the left leg and the other was an episode of syncope, amnesia and dizziness associated with acute sinusitis. Both of these events required hospitalisation.

Table 4.

Treatment-Related Adverse Events, Other than Erosions & Ulcers (ITT Population)α

| Adverse Event | Ibuprofen (N=64) | Ibuprofen-PC (N=61) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| N | % | N | % | |

| General | ||||

| Abdominal Pain | 3 | 4.7 | 3 | 4.9 |

| Fatigue | 1 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Headache | 1 | 1.6 | 1 | 1.6 |

| Digestive | ||||

| Anorexia | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.6 |

| Diarrhoea | 1 | 1.6 | 6 | 9.8 |

| Dry mouth | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.6 |

| Dyspepsia | 4 | 6.3 | 9 | 14.8 |

| Flatulence | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.6 |

| Gastric reflux | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.6 |

| Nausea | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 6.6 |

| Nervous | ||||

| Dizziness | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.6 |

| Respiratory | ||||

| Pharyngitis | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.6 |

| Sinusitis | 1 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Skin and appendages | ||||

| Rash | 1 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

It should be noted that none of the adverse event incidence rates was determined to be statistically significant by treatment group.

The GI related adverse events other than gastroduodenal erosions and ulcers were: dyspepsia (6.3% ibuprofen vs. 14.8% Ibuprofen-PC) and diarrhoea (1.6% ibuprofen vs. 9.8% Ibuprofen-PC), neither of which showed significantly different rates between the two treatment groups. The noted Ibuprofen-PC associated diarrhoea and dyspepsia were transient and self resolved, with a median duration of 4.5 and 8.0 days, respectively. Other adverse events that were observed only in the ibuprofen group were: Helicobacter pylori-associated gastroenteritis (n=1); GI hemorrhage (n=1); and papulous gastropathy (n=1).

Hypertension, which occurred in only 1.6% of the patients taking ibuprofen and 3.3% of the patients taking Ibuprofen-PC, was the only cardiovascular event reported in more than one patient, and no serious cardiovascular adverse events were observed. Considering the recent attention to cardiovascular risk associated with COX-2 inhibitors, it is important to note that both ibuprofen and Ibuprofen-PC were not associated with serious cardiovascular adverse events in this study. These data are consistent with the better cardiovascular safety profile generally attributed to NSAIDs over Coxibs and the fact that this study was of relatively short duration (11).

None of the haematology or blood chemistry assessments showed any statistically significant differences between treatment groups and no trends were discernable. Analysis of various lipid indices also did not reveal any statistically significant differences between the treatment groups.

Physical examinations and vital sign determinations were performed to evaluate safety in the ITT population. No clinically significant abnormal findings were noted for either type of assessment.

Ibuprofen-PC and Ibuprofen had Similar Efficacy in Treating Osteoarthritis

Efficacy was evaluated using the WOMAC and VAS assessments for detection of improvement in osteoarthritis symptoms. As summarized in Table 5, with regards to the changes in WOMAC total scores in the Evaluable for Efficacy population of patients, both treatment groups showed statistically significant improvement over baseline at each study visit. These results were consistent with the subscales for pain, joint stiffness and physical function. Similar positive results were seen in the >55 years of age subset, where both Ibuprofen-PC and ibuprofen significantly decreased WOMAC scores of osteoarthritic patients (not shown). These data were also consistent with VAS assessment of overall improvement in physical functionality over baseline. Ibuprofen and Ibuprofen-PC provided statistically significant improvements over baseline at each study visit. At 6 weeks, ibuprofen treated patients had a (mean ± STD) VAS improvement score of 22.7 ± 20.3, and Ibuprofen-PC group showed a VAS improvement score of 24.4 ± 15.6, both of which were highly statistically significantly different (p<0.001) over baseline. Both treatment agents provided similar analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity based on VAS and WOMAC scores that were not significantly different.

Table 5.

Summary of Percentage Change from Baseline in WOMAC Total Score in All Patients Evaluable for Efficacy Population

| Variable | Visit | Treatment | N | Meana | STD | Paired T-test p-value | T-test p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Change in Total Score | Week 2 | Ibuprofen | 61 | −40.3 | 35.2 | <0.0001* | 0.4033 |

| Ibuprofen-PC | 49 | −35.0 | 30.0 | <0.0001* | |||

|

|

|||||||

| Week 4 | Ibuprofen | 56 | −45.5 | 40.0 | <0.0001* | 0.8945 | |

| Ibuprofen-PC | 52 | −44.6 | 32.1 | <0.0001* | |||

|

|

|||||||

| Week 6 | Ibuprofen | 57 | −52.0 | 37.3 | <0.0001* | 0.8911 | |

| Ibuprofen-PC | 49 | −53.0 | 33.7 | <0.0001* | |||

Statistically significant vs baseline (p-value <0.05).

A negative percentage change indicates improvement for that subscore.

T-tests were performed between the two treatment groups for each visit.

Ibuprofen-PC has Similar Bioavailability to Ibuprofen

Pharmacokinetic (PK) analyses revealed that the two study medications had equivalent ibuprofen bioavailability at baseline and Week 4, with regards to Cmax, tmax and AUC (see Table 6). Intergroup differences in these key PK parameters were minimal among the two treatment groups and were not statistically significantly different, though it appeared that Cmax was modestly increased and tmax decreased in the Ibuprofen-PC group vs ibuprofen. It however should be noted that the pre-dose and post-dose ibuprofen levels were consistently higher at Week 4 than baseline, presumably due to an accumulation of the NSAID in biological fluids over the study period.

Table 6.

Pharmacokinetics of Ibuprofen and Ibuprofen-PC After Initial Dose and Repeated Administration Over 4 Weeks in Evaluable Patients

| Treatment | PK Parameter | Day 0 | Week 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| N | Mean ± STD | N | Mean ± STD | |||

| Ibuprofen | Cmax (mg/L) | 64 | 53.0 ± 20.0 | 59 | 58.6 ± 19.3 | |

| Ibuprofen-PC | Cmax (mg/L) | 61 | 62.5 ± 24.8 | 54 | 71.0 ± 21.1 | |

|

| ||||||

| Ibuprofen | tmax (min) | 64 | 80.6 ± 27.5 | 59 | 81.7 ± 28.0 | |

| Ibuprofen-PC | tmax (min) | 61 | 76.7 ± 27.6 | 54 | 76.3 ± 25.1 | |

|

| ||||||

| Ibuprofen | AUC0-t (mg/L*min) | 64 | 4120 ± 1839 | 59 | 4663 ± 1835 | |

| Ibuprofen-PC | AUC0-t (mg/L*min) | 61 | 4583 ± 2187 | 54 | 5089 ± 1910 | |

DISCUSSION

The present study evaluated gastroduodenal mucosal injury and therapeutic efficacy of ibuprofen and Ibuprofen-PC at a dose of 2400 mg/day of active ingredient for 6 weeks in osteoarthritis (OA) patients. The rationale for this approach, which was briefly described earlier, is based upon evidence that: 1) the gastric mucosa of both laboratory animals and humans possess non-wettable, hydrophobic characteristics that are attributable to surface-active phospholipids, notably PC within or on the surface of the mucus gel layer (13, 14); 2) NSAIDs have a chemical affinity to associate with PC, and in doing so induce a rapid attenuation of the surface hydrophobic barrier properties of the stomach (13–16); and 3) NSAIDs pre-associated with either synthetic or natural (soy) PC were found to be less toxic to the GI tract of rodents and human volunteers evaluated in a 4-day cross-over pilot clinical trial (15, 17). Ibuprofen was selected as a representative NSAID to associate with PC in order to examine its GI safety in this longer (6 week) study, as it is commonly used by OA patients and is known to induce reproducible therapeutic efficacy and gastroduodenal injury when administered at an anti-arthritic dose of 2,400 mg/day (1–5).

In this study it was determined that in the total evaluable population of OA patients aged 18–81 years of age, Ibuprofen-PC was similar to ibuprofen with regards to both bioavailability and efficacy to treat arthritis symptoms, while reducing the NSAID’s ability to induce gastroduodenal erosions and ulcers; however in this total evaluable population, the GI-protective effect did not reach statistical significance. As anticipated, ibuprofen alone induced significant gastroduodenal injury comparable to previous observations (21). Interestingly, upon post-hoc analysis it was determined that Ibuprofen-PC was safer in patients >55 years of age (with a mean age of 64 years) who are most at risk of developing NSAID-induced gastroduodenal injury. In this clinically-relevant subgroup, Ibuprofen treated patients had significantly greater absolute change in Lanza scores and were 3.7 times more likely (or a 270% increased risk) to develop multiple gastroduodenal erosions (Lanza score > 2) than the Ibuprofen-PC treated patients. Although we did evaluate treatment differences using other age cut-offs as demonstrated in Figure 2, the >55 years comparison was used for statistical reasons, as it represented the median age of the study population, and meaningful statistical analyses of the older age groups could not be accomplished due to the small number of subjects in these subgroups.

Numerous pilot studies have used erosions as surrogate markers of ulcers that have been linked to life threatening GI perforation and hemorrhage. The rate of erosions of Ibuprofen-PC appears to be consistent with the rate of erosions found in trials using meloxicam, rofecoxib, celecoxib and the combination of naproxen/cimetidine (18, 21–23). As the latter agents have been shown to have lower ulcer rates than traditional NSAIDs, erosions may be an important surrogate marker of ulcers. In a more conservative approach, only the frequency of multiple erosions or a Lanza Score of >2 were compared. The reduction of such gastroduodenal lesions accurately predicted the GI safety of rofecoxib as assessed by the reduction in perforations, hemorrhage and other outcome measures, suggesting that improvement afforded by the PC formulation of ibuprofen may be clinically relevant and warrants further testing (6, 21). It should be noted that although performing post-hoc analyses on a subset of the study population is not ideal, we do believe that the rationale for evaluating the effects of our treatment on the cohort of subject >55years of age who are most characteristic of OA patients at risk of developing NSAID-induced GI adverse events, is sound. Clearly, the use of an endoscopic study using a Lanza scoring method as an index of GI toxicity of a test drug has limitations, and the definitive demonstration of the GI-safety of Ibuprofen-PC will have to await future clinical outcome studies performed over an extended dosing period (1–2 years) in a large population of OA subjects.

This improved safety of Ibuprofen-PC was observed at therapeutic doses for the treatment of osteoarthritis. When administered at a dose of 2400 mg/day of the NSAID for 6 weeks, ibuprofen provided clear anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity over baseline. As expected, the therapeutic effectiveness of Ibuprofen-PC was comparable to that of ibuprofen as assessed by both WOMAC and VAS scoring systems. These data are consistent with the results of pharmacokinetic analyses performed at baseline and at week 4. There was no indication of significant accumulation or a depot effect during chronic administration of Ibuprofen-PC over that of ibuprofen, although there was a suggestion of a small yet comparable accumulation of the NSAID in biological fluids in both patient populations during a period of chronic dosing.

Ibuprofen-PC was well tolerated with no marked changes in the incidence of adverse events, compared with ibuprofen. While there appears to be a trend that total evaluable OA patients taking Ibuprofen-PC had fewer symptomatic clinically diagnosed gastric ulcers than encountered in patients taking the equivalent dose of ibuprofen, as indicated above more comprehensive studies are warranted to validate these initial observations. An apparent increase in the rate of dyspepsia and diarrhoea was noted. Although this may be due to a general shift to milder (non-ulcer) GI symptoms in OA patients taking Ibuprofen-PC, the possibility of co-administering 2400 mg/day of NSAID-associated lecithin oil along with ibuprofen in the proprietary formulation, as a contributing factor, cannot be eliminated. The relatively low incidence of diarrhoea (<10%) with Ibuprofen-PC and it’s transient nature (duration of <5 days) and may not represent a major compliance issue for chronic administration of Ibuprofen-PC.

The mechanism of age related NSAID-induced GI toxicity is unknown. However, age associated decreases in surface hydrophobicity, prostaglandin levels and impaired healing may contribute to the deterioration of the barrier property of the mucosa. Interestingly, Hacklesberger et al observed an age related decrease in surface hydrophobicity in the antrum of the stomach, which is also the primary site of NSAID-induced ulcers (24).

PC is the major surfactant phospholipid that confers surface hydrophobic characteristics to the gastric mucosa. It is possible that with age, surface phospholipid levels decrease below a critical threshold and this reduction contributes to age related NSAID intolerance. Although the mechanism of the age-specific decrease in gastroduodenal erosions afforded by the Ibuprofen-PC formulation is unknown, this protection may be consistent with the proposed mechanism of PC mediated protection against NSAID-induced GI toxicity. Our working hypothesis is that ibuprofen, when administered as a PC-enriched lecithin oil, forms mixed micelles which prevent the NSAID from interacting with host phospholipids within or on the luminal surface of the mucus gel layer. Without barrier disruption, NSAID-induced acid back-diffusion into the mucosa would be reduced. Below a critical level of intrinsic surfactant phospholipids within or coating the mucus gel layer, the administration of NSAIDs chemically pre-associated with PC may be beneficial in mitigating NSAID-induced surface injury to the gastroduodenal mucosa and the subsequent development of erosions and ulcers. Irrespective of the mechanism, Ibuprofen-PC appears significantly safer than ibuprofen in osteoarthritic patients 55 years of age and older, who are most at risk of developing NSAID-induced gastroduodenal injury and hence this novel NSAID formulation warrants additional clinical testing.

Acknowledgments

The following persons and institutions participated in the clinical study: Frank L Lanza, MD, Houston Institute of Clinical Research, Houston, TX; Bhupinderjit S Anand, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX; Howard I Schwartz, MD, Miami Research Associates, Miami, FL; Michael Schwartz, MD, Jupiter Research Associates, Jupiter, FL; Garth Denyer, MD, Oaks Medical Center, Spring, TX; and Martin Caperton, MD, Sadler Clinic, Spring, TX. Synergos/InVentiv (Woodlands, TX) served as the Clinical Research Organization coordinating the six centers involved in the study, and performed the statistical analyses of the results presented.

The authors wish to thank Drs. Elizabeth Dial, Brendan Whittle and Mr. Jason Moore for their review of the manuscript and helpful suggestions to improve it.

Footnotes

STATEMENT OF INTERESTS:

Personal interests: Dr. Frank Lanza has served as a consultant to Merck & Company, Inc., and Procter & Gamble, received honoraria from TAP Pharmaceutical Products Inc, and AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, received research funding from Pfizer Inc, Merck& Company Inc, and PLx Pharma Inc., and has financial interests in Merck (stock held in IRA) and Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Lenard Lichtenberger has served as a consultant and received research funding from PLx Pharma Inc, owns stock in PLx Pharm Inc, and is the primary inventor of several patents owned by The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston over the composition and use of Ibuprofen-PC which have been licensed to PLx Pharm Inc. Dr. Bhupinderjit Anand has received research funding from Hoffmann LaRoche and Schering Plough. Dr. Upendra Marathi is an employee and owns stock in PLx Pharma Inc.

Funding interests: This study was funded in part by NIH grants R03 DK59403, P30DK 056338 and R42 DK063882, and by PLx Pharma Inc.

References

- 1.Singh G. Recent considerations in nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastropathy. Am J Med. 1998;105(1B):31S–38S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe MM, Lichtenstein DR, Singh G. Gastrointestinal toxicity of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1888–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906173402407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.IMS Heath. National Prescription Audit Plus™. 2004. Jan-Dec [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lanza FL. A guideline for the treatment and prevention of NSAID-induced ulcers. Amer J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:2037–2046. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Logan R. Risk of adverse gastrointestinal outcomes in patients taking cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors or conventional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: population based nested case-control analysis. BMJ. 2005;331:1310–1316. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7528.1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, et al. VIGOR Study Group. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. VIGOR Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1520–1528. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverstein FE, Faich G, Goldstein JL, et al. Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: the CLASS study: A randomized controlled trial. Celecoxib Long-term Arthritis Safety Study. JAMA. 2000;284:1247–1255. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.10.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverstein FE, Graham DY, Senior JR, et al. Misoprostol reduces serious gastrointestinal complications in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:241–249. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-4-199508150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan FK, Chung SC, Suen BY, et al. Preventing recurrent upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with Helicobacter pylori infection who are taking low-dose aspirin or naproxen. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:967–973. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103293441304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pham K, Hirschberg R. Global safety of coxibs and NSAIDs. Curr Top Med Chem. 2005;5:465–473. doi: 10.2174/1568026054201640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caldwell B, Aldington S, Weatherall M, Shirtcliffe P, Beasley R. Risk of cardiovascular events and celecoxib: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J R Soc Med. 2006;99:132–140. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.99.3.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davenport HW. Gastric mucosal injury by fatty and acetyl salicylic acid. Gastroenterology. 1964;46:245–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lichtenberger LM. Where is the evidence that cyclooxygenase inhibition is the primary cause of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced gastrointestinal injury: Topical injury revisited. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;61:631–637. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00576-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kao Y-CJ, Goddard PJ, Lichtenberger LM. Morphological effects of aspirin and prostaglandin on the canine gastric mucosal surface: analysis with a phospholipid cytochemical stain. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:592–606. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lichtenberger LM, Wang ZM, Romero JJ, et al. NSAIDs associate with zwitterionic phospholipids: Insight into the mechanism and reversal of NSAID-induced GI injury. Nature Med. 1995;1:154–158. doi: 10.1038/nm0295-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giraud MN, Motta C, Romero JJ, Bommelaer G, Lichtenberger LM. Interaction of indomethacin and naproxen with gastric surface-active phospholipids: a possible mechanism for the gastric toxicity of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;57:247–254. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anand BS, Romero JJ, Sanduja SK, et al. Phospholipid association reduces the gastric mucosal toxicity of aspirin in human subjects. Amer J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1818–1822. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lanza FL, Graham DY, Davis RE, Rack MF. Endoscopic comparison of cimetidine and sucralfate for prevention of naproxen-induced acute gastroduodenal injury: Effect of scoring method. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:1494–1499. doi: 10.1007/BF01540567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenwald DA. Aging, the gastrointestinal tract, and risk of acid-related disease. Am J Med. 2004;117 (Suppl 5A):8S–13S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pilotto A. Aging and upper gastrointestinal disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lanza FL, Rack MF, Simon TJ, et al. Specific inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 with MK-0966 is associated with less gastroduodenal damage than either aspirin or ibuprofen. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:761–767. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang DM, Young TH, Hsu CT, Kuo SY, Hsieh TC. Endoscopic comparison of the gastroduodenal safety and the effects on arachidonic acid products between meloxicam and piroxicam in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2001;20:104–113. doi: 10.1007/pl00011190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simon LS, Lanza FL, Lipsky PE, et al. Preliminary study of the safety and efficacy of SC-58635, a novel cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor: efficacy and safety in two placebo-controlled trials in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, and studies of gastrointestinal and platelet effects. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1591–602. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199809)41:9<1591::AID-ART9>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham DY. NSAID ulcers; prevalence and prevention. Mod Rheumatol. 2000;10:2–7. doi: 10.3109/s101650070031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hackelsberger A, Platzer U, Nilius M, et al. Age and Helicobacter pylori decrease gastric mucosal surface hydrophobicity independently. Gut. 1998;43:465–469. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.4.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]