Abstract

Background & Aims

Mathematical modeling of hepatitis C virus (HCV) kinetics indicated that the cellular immune response contribute to interferon (IFN)-induced clearance of HCV. We investigated a potential role of natural killer (NK) cells in this process.

Methods

Phenotype and function of blood and liver NK cells were studied during the first 12 weeks of treatment with pegylated IFN-alfa and ribavirin, the time period used to define the early virological response.

Results

Within hours of treatment initiation, NK cells of patients that had an early virological response increased expression of the activating receptors NKG2D, NKp30, and CD16; they decreased expression of NKG2C and 2B4, along with the inhibitory receptors SIGLEC7 and NKG2A, resulting in NK cell activation. NK cell cytotoxicity, measured by degranulation and TRAIL production, peaked after 24 h (P<.01), concomitant with an increase in alanine aminotransferase levels (P<.05), whereas IFN-g production decreased within 6 h and did not recover for more than 4 weeks (P<.05). NK cells from liver biopsies taken 6 h after treatment initiation had increased numbers of cytotoxic CD16+ NK cells (P<.05) and a trend towards increased production of TRAIL. Degranulation of peripheral blood NK cells correlated with the treatment-induced, first phase decreases in viral load (P<.05) and remained higher in early virological responders than in nonresponders for weeks.

Conclusions

IFN activates NK cells early after treatment is initiated. Their cytotoxic function, in particular, is strongly induced, which correlates to the virologic response. Therefore, NK cell activation indicates responsiveness to IFN-g–based treatment and indicates the involvement of the innate immune cells in viral clearance.

Keywords: liver disease, HCV treatment, response to therapy, cell death, ALT

Introduction

Current treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection consists of a 24 or 48-week course of pegylated interferon-alfa (IFN-α) and ribavirin. It is important to understand the mechanisms of interferon-induced HCV clearance because only about 50% of the treated patients achieve a sustained response and because interferon will remain an important component of new treatment regimens with direct antiviral agents 1. Based on mathematical modeling of serum HCV titers during treatment it has been proposed that an IFN-α-mediated block of HCV replication and virion release causes the first phase, i.e. 48h decline in serum HCV titer 2. This rapid reduction of viremia is followed by a slower, second phase decline, thought to represent the elimination of infected hepatocytes 2. Owing to IFN-α’s immunomodulatory activities, the elimination of HCV-infected hepatocytes is likely immune-mediated. However, the immune cells responsible for the elimination of infected hepatocytes have not been identified thus far.

Multiple studies have concluded that HCV-specific T cells do not contribute to treatment-induced HCV clearance (reviewed in 3). In fact, HCV-specific CD8+ T cell responses decline during IFN-based therapy and treatment outcome is neither associated with the strength nor quality of HCV-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses 3.

Several findings prompted us to study NK cells in the context of hepatitis C treatment. First, NK cells are the most prevalent lymphocyte subset in the liver constituting about 30% of intrahepatic lymphocytes 4. Second, the current treatment regimen for chronic hepatitis C includes IFN-α, a potent activator of NK cells 5. Third, the genotype for certain receptors regulating NK cell activity is associated with a higher likelihood of spontaneous and treatment-induced HCV clearance 6, 7.

NK cells are controlled by the integration of signals from activating and inhibitory cell surface receptors, which include killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs), lectin-like receptors (NKG2A-F) and natural cytotoxicity receptors (NKp30, NKp44 and NKp46). In the absence of inflammation or infection, NK cells receive mostly inhibitory signals. NK cell activation occurs when signaling through activating receptors overcomes inhibition. In addition, NK cells can get activated by inflammatory cytokines such as type I interferons (IFN-α and IFN-β) and IL-12 that are commonly released in response to virus infections 5.

In regards to effector functions, NK cells have traditionally been divided into different effector subsets based on expression of CD56 and CD16. CD56bright NK cells constitute about 10% of the peripheral blood NK cell population, do not express CD16 and are considered the main producers of cytokines and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) 8. TRAIL binds to the death receptors DR4 and DR5 on target cells and induces apoptosis. The more mature CD56dim NK cell subset makes up the remaining 90% of the NK cell population. These cells express high levels of CD16 and exert mostly cytotoxic effector functions by perforin/granzyme. However, the traditional division of NK cells in two main subsets with distinct functions has recently been challenged when CD56dim NK cells were found to produce large amounts of cytokines within the first 2-4h after activation 9, 10.

In HCV infection, NK cells have been shown to display an activated phenotype with increased expression of receptors such as NKG2C, NKp30, NKp44, NKp46 and CD122 11–13. Activation is enhanced in the liver as compared to the blood, and cytotoxic NK cell effector functions, as determined by degranulation and TRAIL production, correlate with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, a marker of liver injury 12. Increased TRAIL production was also observed in spontaneous hepatitis B flares, possibly due to endogenous IFN-α14, and during IFN-α-based therapy of chronic hepatitis C 15.

In the current study we performed a detailed analysis of changes in NK cell phenotype and function during interferon-based treatment of chronic hepatitis C and correlated the results with the virological response.

Materials and Methods

Study cohort

Peripheral blood NK cells were studied in patients with chronic hepatitis C (Suppl. Table 1). Twenty-two patients achieved an early virological response (EVR) with peginterferon (PegIFN) alfa-2a (180 µg/week s.c.) and weight-based ribavirin (RBV, 1000 mg for <75 kg bodyweight and 1200 mg for ≥75 kg bodyweight p.o daily for HCV genotypes 1 and 4; 800 mg p.o. daily for HCV genotypes 2 and 3). An EVR is defined as serum HCV RNA being either undetectable (< 15 IU/ml) or 2 log10 lower at week 12 than prior to treatment. Sampling time points were 4 weeks, 2 weeks and 0 h prior to treatment, and 6 h, 24 h, 48 h, 1 week, 2 weeks, 4 weeks and 12 weeks after initiation of treatment. One patient discontinued treatment after week 4 and was therefore only included in the correlation of NK cell and first phase virological response.

Fifteen patients with a history of nonresponse to standard PegIFN/RBV therapy (referred to as nonresponders) were studied in a PegIFN/RBV re-treatment study 16 to correlate NK cell responses with the first phase virological decline. These patients were studied 4 weeks and immediately (0 h) prior to re-treatment and 8 h, 24 h, 48 h, 1 week and 2 weeks after initiation of PegIFN/RBV re-treatment. They continued pegIFN/RBV treatment for a full treatment course, but S-adenosyl methionine was added after the initial 2 weeks 16 and NK cell responses were therefore not studied beyond the initial 2 weeks.

Intrahepatic NK cells were studied in 29 patients who were randomized to undergo liver biopsies either immediately prior to (n=19), or 6 h after (n=9) initiation of PegIFN/RBV therapy. Six and 4 of these patients, respectively, had been pretreated with RBV for 4 weeks and their intrahepatic NK cell phenotype did not differ from those who had not been pretreated (not shown). All subjects gave written informed consent for research testing under protocols approved by the NIDDK Institutional Review Board.

Lymphocyte isolation

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were separated from ACD-anticoagulated blood on Ficoll-Histopaque (Mediatech, Manassas, VA) density gradients and washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS; Mediatech). Cryopreserved and thawed PBMCs were used for the prospective study and fresh PBMCs were used for the cross-sectional study to compare peripheral blood and liver NK cells. Liver tissue was homogenized, washed with PBS and liver-infiltrating lymphocytes (LIL) were directly stained with the antibodies indicated below.

Viral kinetics

HCV RNA levels were measured using Cobas TaqMan real-time PCR (Roche Diagnostics, Palo Alto, CA), with a lower limit of detection of 15 IU/mL. The first phase virological response was defined as the decline in HCV RNA titer during the first 48 h of therapy.

NK cell analysis

NK cells were studied as previously described 12 using an LSRII using FacsDiva Version 6.1.3 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and FlowJo Version 8.8.2 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR) software.

(i) NK cell frequency and phenotype

All phenotyping panels included ethidium monoazide (EMA), anti-CD19-PeCy5 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and anti-CD14-PeCy5 (Serotec, Raleigh, NC) to exclude dead cells, B cells and monocytes, respectively, anti-CD56-PeCy7, anti-CD3-AlexaFluor700 and anti-CD16-PacificBlue (BD Biosciences) to identify NK cells. In addition, we used FITC-conjugated antibodies against CXCR3, CD122 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), CD69 (BD Biosciences), CD244 (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA), SIGLEC7 (Lifespan Biosciences, Seattle, WA), PE-conjugated antibodies against NKG2A, NKG2D, NKp44 (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA), TRAIL (BD Biosciences), CD300 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and APC-conjugated antibodies against CCR5 (BD Biosciences), NKp30, NKp46 (Miltenyi, Auburn, CA), NKG2C (R&D Systems), CD85j (ILT2) (eBiosciences). LIL were stained with anti-CXCR3-FITC, anti-TRAIL-PE, anti-CD16-PacificBlue and anti-CD69-APC (BD Biosciences) in addition to EMA and lineage-specific antibodies as described above.

(ii) NK cell degranulation

PBMCs were thawed and cultured overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2 in RPMI1640 with 10% fetal calf serum (Serum Source International, Charlotte, NC), 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES (Cellgro, Manassas, VA) without exogenous IL-2. The next day, PBMCs were counted and stimulated in the presence or absence of K562 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) to assess degranulat ion as described 12 but without additional cytokines.

(iii) Cytokine release

PBMCs were incubated with or without IL-12 (0.5 ng/ml; R&D Systems) and IL-15 (20 ng/ml R&D Systems) for 14 h, followed by addition of brefeldin A for 4 h and intracellular staining for IFN-γ12.

Alanine aminotransferase levels

Serum ALT levels were determined with a colorimetric assay (Teco Diagnostics, Anaheim, CA) and shown relative to the pretreatment (0 h) value.

Genotyping

DNA samples were genotyped for the IL28B rs12979860 polymorphism with a TaqMan SNP genotyping assay (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA, USA) and for KIR/HLA compound haplotypes as described 17.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism Version 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA) and JMP (SAS Inc. Cary, NC). The Mann-Whitney nonparametric two-sample rank test was used to compare liver NK cells, the Wilcoxon matched paired test to compare ALT values. Serial measures ANOVA was used to compare NK cells from responders and nonresponders throughout the treatment course. Changes in NK cell phenotype and function during treatment were analyzed by serial measures ANOVA. Because this test is based on the assumption of a linear model and does not reflect the specific pattern of marker expression (e.g. an early increase followed by a plateau or a decrease) we also used paired Student t-tests to compare individual treatment time points to the 0h value. Pearson correlation analysis was performed to study changes in NK cell degranulation in relation to viral kinetics. A two-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Changes in NK cell phenotype of EVR patients during PegIFN/RBV therapy

To study the effect of IFN-α-based therapy on NK cells we assessed the phenotype and function of this lymphocyte subset prospectively in the blood of patients with chronic HCV infection who received PegIFN/RBV therapy. To characterize optimal changes in NK cell phenotype and function we initially focused on the 22 patients who mounted an EVR.

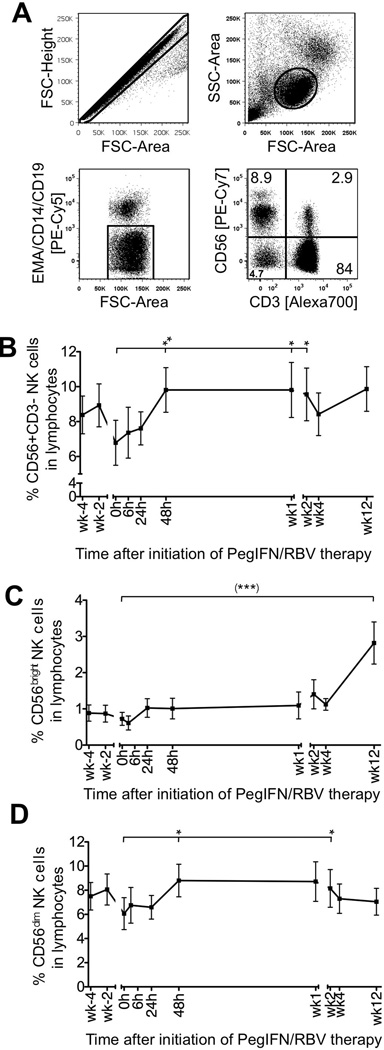

NK cells were identified as CD3-CD56+ cells by multicolor flow cytometry after gating on single cells (forward scatter–height versus forward scatter–area), lymphocytes (forward scatter versus side scatter), and exclusion of CD14+ monocytes, CD19+ B cells and EMA+ dead cells (Fig. 1A). As shown in figure 1B the frequency of NK cells in the blood lymphocyte population increased during the first 2 days of therapy (6.79%±1.29%, mean±SEM at 0 h compared to 9.81%±1.28% 48 h later, P<0.01) and was maintained at that level for 2 weeks. This was paralleled by an increase in CD56bright (Fig. 1C) and CD56dim cells (Fig. 1D). CD56bright cells increased further from week 2 (1.40±0.40%) to week 12 (2.18±0.58%), but CD56dim cells did not.

Figure 1. Frequency of NK cells and their subsets during PegIFN/RBV therapy.

(A) Gating strategy. (B–D) Frequency of CD56+CD3− NK cells (B) and their CD56bright (C) and CD56dim subsets (D) in PBMCs during PegIFN/RBV therapy. Mean ± SEM are shown (n=22 patients). h, hour; wk, week. (***) P<0.001 with repeated measures ANOVA; *P≤0.05, ** P<0.01 with paired Student t-test comparing the indicated individual time points to the 0 h time point.

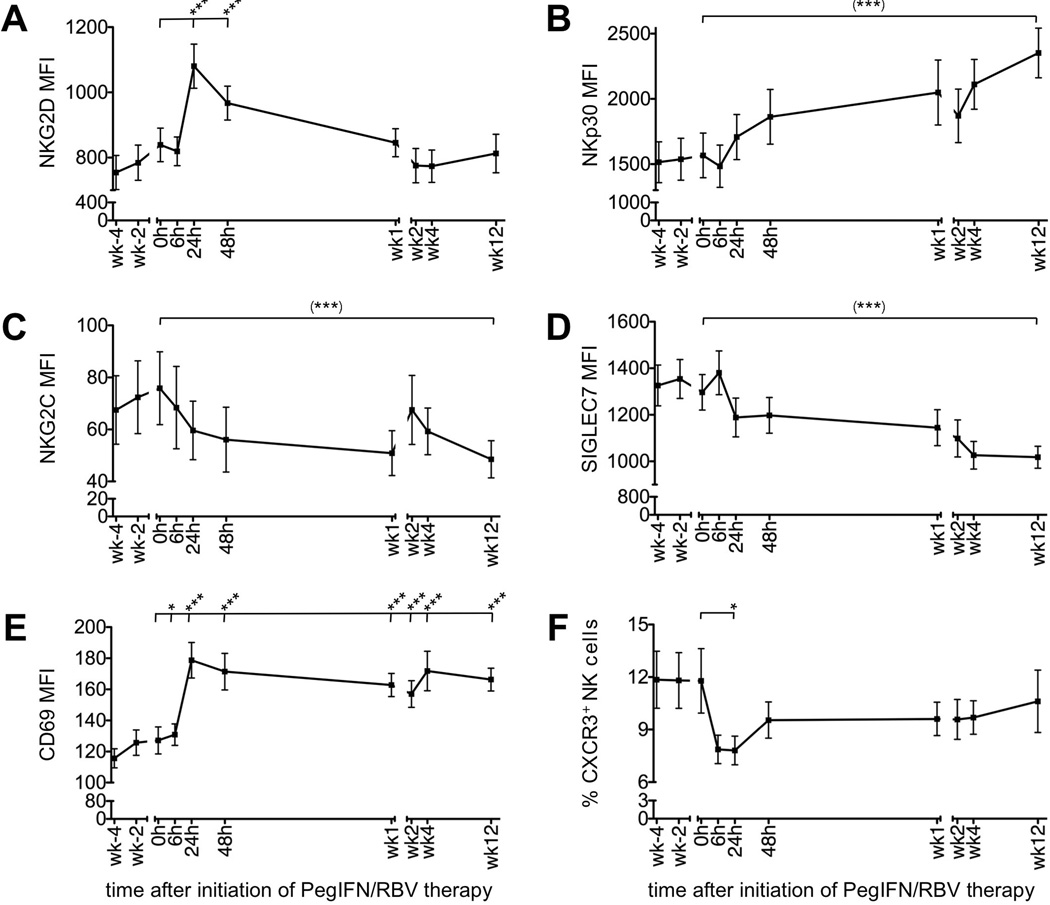

For a detailed NK phenotype analysis PBMCs were stained for activating and inhibitory NK cell receptors, activation markers and chemokine receptors (Suppl. Fig. 1). Figure 2 details significant changes in the bulk NK cell population during the first 12 weeks of therapy. For example, the expression level of the activating receptor NKG2D peaked as early as 24 h after initiation of therapy (MFI of 839±51 at 0 h; 1080±68 24 h later, P<0.001 Fig. 2A) and the expression level of NKp30 increased steadily until at least week 12 of therapy (MFI of 1567±171 at 0 h; 2352±190 at week 12, P<0.0001, Fig. 2B), and this observation was most pronounced for the CD56dim NK cell population (Suppl. Fig. 2B). NKp44 and NKp46 expression remained unaltered (not shown), 2B4 expression was slightly downregulated (MFI of 1019±48 at 0 h; 919±35 at week 1, P<0.01; not shown) and NKG2C expression decreased significantly (MFI of 76±14 at 0 h; 49±7 at week 12, P=0.0004, Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. Phenotype of peripheral blood NK cells during PegIFN/RBV therapy.

(A–E) MFI of NKG2D (A), NKp30 (B), NKG2C (C), SIGLEC7 (D) and CD69 expression (E) on CD56+CD3− NK cells. (F) Frequency of CXCR3+ cells in the CD56+CD3− NK cell population. Mean ± SEM are shown (n=22 patients). h, hour; wk, week. (***) P<0.001 with repeated measures ANOVA; *P≤0.05, *** P<0.001 with paired Student t-test comparing the indicated individual time points to the 0 h time point.

Within the group of inhibitory receptors, SIGLEC7 expression decreased significantly during the first 12 weeks of therapy (MFI of 1297±76 at 0 h; 1018±47 at week 12, P<0.0001, Fig. 2D) and this decrease was most pronounced in the CD56dim population (Suppl. Fig. 2). NKG2A expression was slightly reduced at the 6 h time point (MFI of 984±134 at 0 h, compared to 850±101 at 6 h, P=0.46), but elevated at week 12 of treatment (MFI of 1344±156, P=0.007, not shown) due to the increase in CD56bright NK cells (Fig. 1C). CD85j and CD300 expression remained unaltered (data not shown). Collectively, these data suggest a trend towards increased NK cell activation and less inhibition. Consistent with this interpretation, expression of the activation marker CD69 increased significantly as early as 24 h after initiation of therapy in the bulk NK cell population (Fig. 2E) and both the CD56bright and CD56dim subset (Suppl. Fig. 2) and increased expression was maintained throughout the observation period.

Finally, we analyzed expression of chemokine receptors associated with lymphocyte recruitment to the liver. Interestingly, the frequency of CXCR3+ (Fig. 2F) and CCR5+ NK cells (not shown) in the blood decreased significantly as early as 6 h after initiation of therapy (CXCR3+ NK cells 11.4%±1.8% at 0 h, 7.7%±0.8% at 24 h, P=0.034; CCR5+ NK cells 8.8%±0.8% at 0 h, 6.5%±0.6% at 6 h; P=0.001), which may indicate recruitment of chemokine receptor-positive NK cells from the blood to the site of infection.

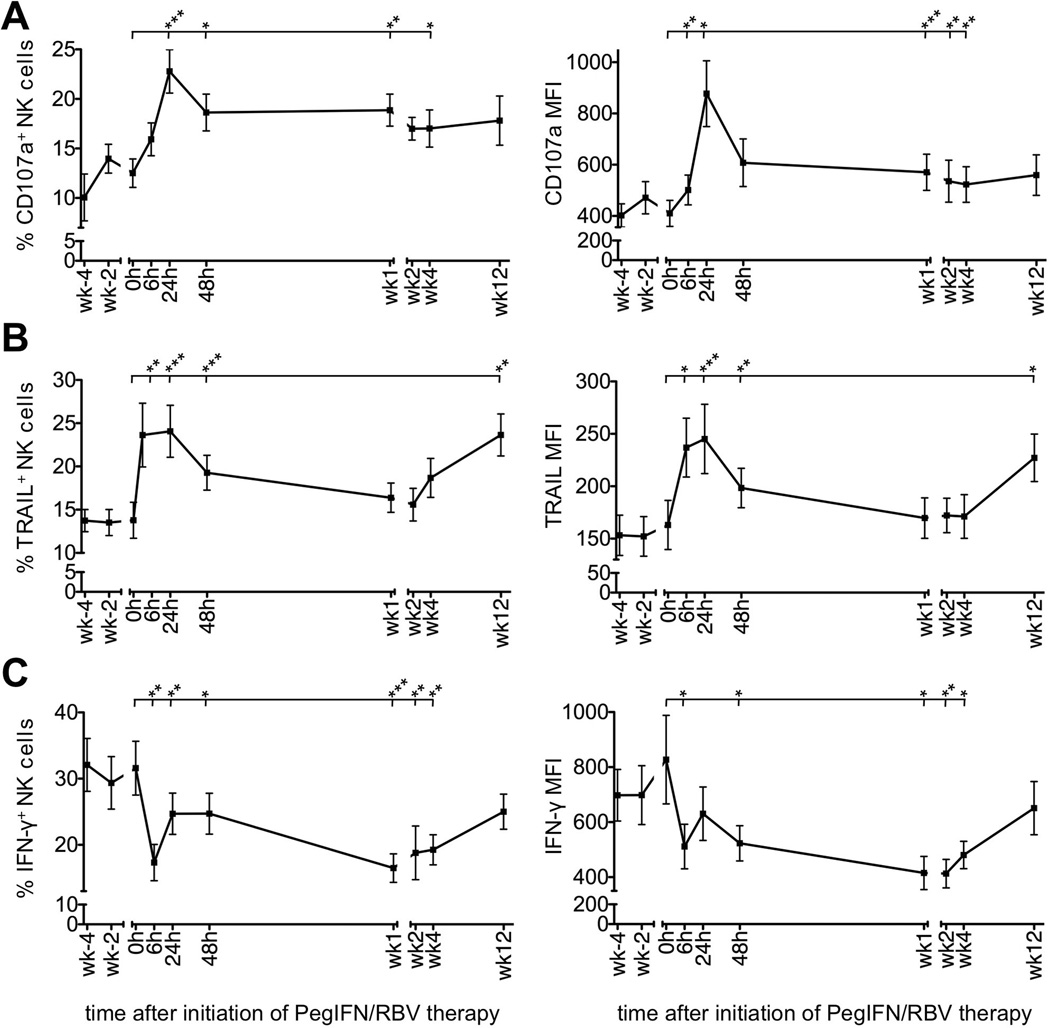

PegIFN/RBV therapy polarizes NK cell function towards increased degranulation and TRAIL production but decreased IFN-γ production

NK cells mediate anti-viral effects by killing infected cells and by producing antiviral and immunomodulatory cytokines such as IFN-γ. To assess changes in NK cell cytotoxicity during therapy we incubated PBMCs with the MHC-negative target K562 and measured degranulation by staining CD107a on the cell surface (Suppl. Fig. 1). A significant increase in both the frequency of CD107a+ NK cells and their CD107a expression level was observed within 24 h of treatment (CD107a+ NK cells 12.5%±1.4% at 0 h, 22.8%±2.2% at 24 h; MFI of 410±51 at 0 h, 877±128 at 24 h; Fig. 3A) and was maintained for at least 4 weeks. Consistent with these results ex vivo expression of TRAIL, a mediator of NK cell cytotoxicity, increased (TRAIL+ NK cells 13.8%±2.1% at 0 h, 24.1%±3.0% at 24 h; MFI of 163±23 at 0 h, 245±33 at 24 h, Fig. 3B). This was observed for both CD56dim and CD56bright NK cells (not shown).

Figure 3. PegIFN/RBV therapy polarizes NK cell function towards increased degranulation and TRAIL production and decreased IFN-γ production.

(A–C) Changes in NK cell CD107a (A), TRAIL (B) and IFN-γ expression (C) during PegIFN/RBV therapy. Mean ± SEM of NK cell frequency and MFI are shown in 21, 20 and 22 patients, respectively. Statistical analysis: paired Student t-test comparing the indicated individual time points to 0 h. h, hour; wk, week. *P≤0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001.

In contrast to NK cell cytotoxicity, IFN-γ production was suppressed as early as 6 h after initiation of therapy (IFN-γ+ NK cells 31.2%±3.9% at 0 h, 17.7%±2.7% at 6 h; MFI of 806±155 at 0 h, 511±81 at 6 h; Fig. 3C). Although the frequency of IFN-γ+ NK cells and their mean IFN-γ expression level had slightly recovered by 24 h and 48 h, it took at least 12 weeks for both parameters to reach pretreatment levels (Fig. 3C). The recovery of IFN-γ production from week 4 to week 12 of treatment paralleled an increase in the percentage of CD56bright cells.

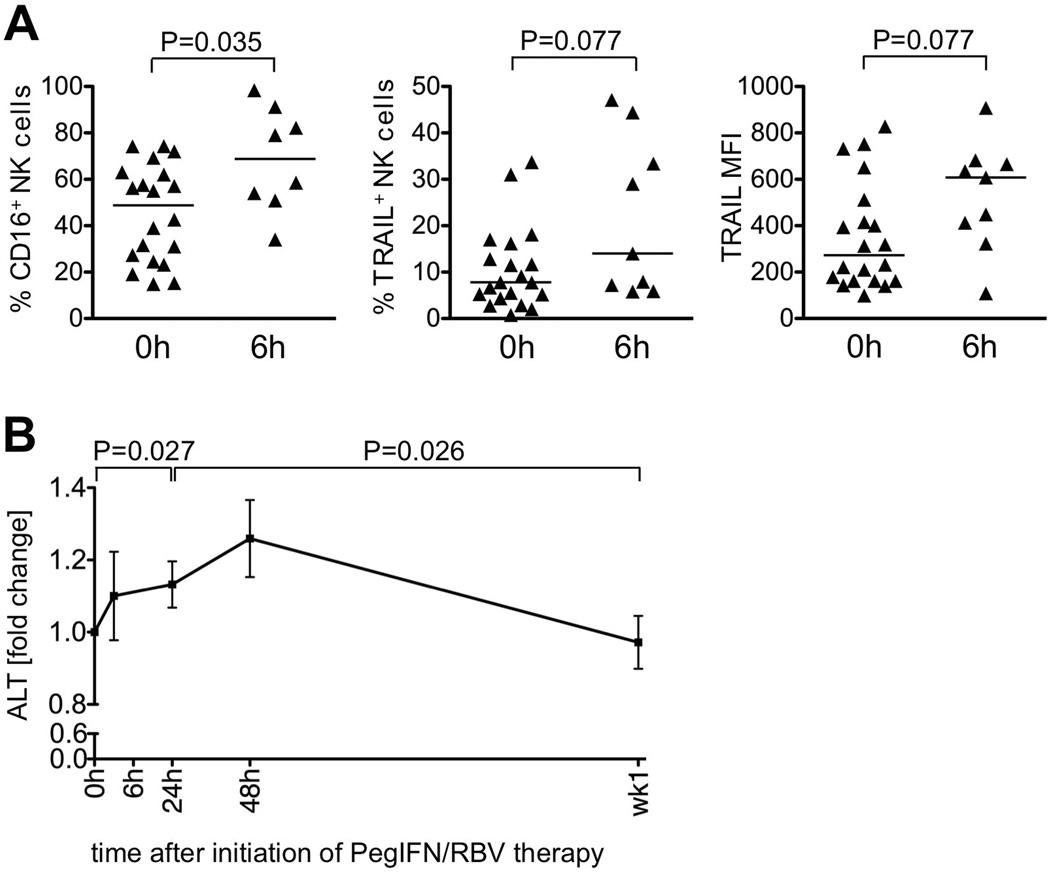

Increase of cytotoxic intrahepatic NK cells during the early phase of PegIFN/RBV therapy

The antiviral function of NK cells is exerted in the liver, the site of HCV replication. We therefore performed a cross-sectional analysis of intrahepatic NK cells in patients who were randomized to undergo liver biopsy either immediately prior to (0 h) or 6 h after initiation of PegIFN/RBV therapy. As shown in the left panel of figure 4A, the size of the intrahepatic CD16+ NK cell subset, the main mediators of cytotoxicity, increased 6 h after initiation of therapy compared to baseline. Likewise, the percentage of TRAIL-expressing NK cells (Fig. 4A middle panel) and the TRAIL expression level (MFI) increased (Fig. 4A, right panel). In contrast, TRAIL expression on T cells was only marginally increased at 6 h of treatment in liver and blood (data not shown).

Figure 4. Changes in the intrahepatic NK cell subset during the early phase of PegIFN/RBV therapy.

(A) The size of the CD16+ NK cell subset, the percentage of TRAIL-expressing NK cells and the TRAIL MFI in a cross-sectional analysis of patients who were randomized to undergo liver biopsies either immediately prior to (n=19), or 6 h after (n=9) initiation of PegIFN/RBV therapy. Lines indicate the median.

(B) Relative serum ALT levels during PegIFN/RBV therapy. Statistical analysis: Wilcoxon matched paired test comparing the individual time points to 0 h. Mean ± SEM are shown; h, hour; wk, week.

Collectively, the observed phenotypic and functional changes in circulating and intrahepatic NK cells within the first 6 h of therapy are consistent with an increase in cytotoxicity. As a clinical correlate of hepatocyte turnover we measured serum ALT levels. Indeed, serum ALT levels increased slightly within the first 24 h (P=0.027 compared to 0 h) and peaked at the 48 h time point (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that hepatocytes are dying during the first 48 h of treatment.

Degranulation of NK cells correlates with virological response during PegIFN/RBV therapy

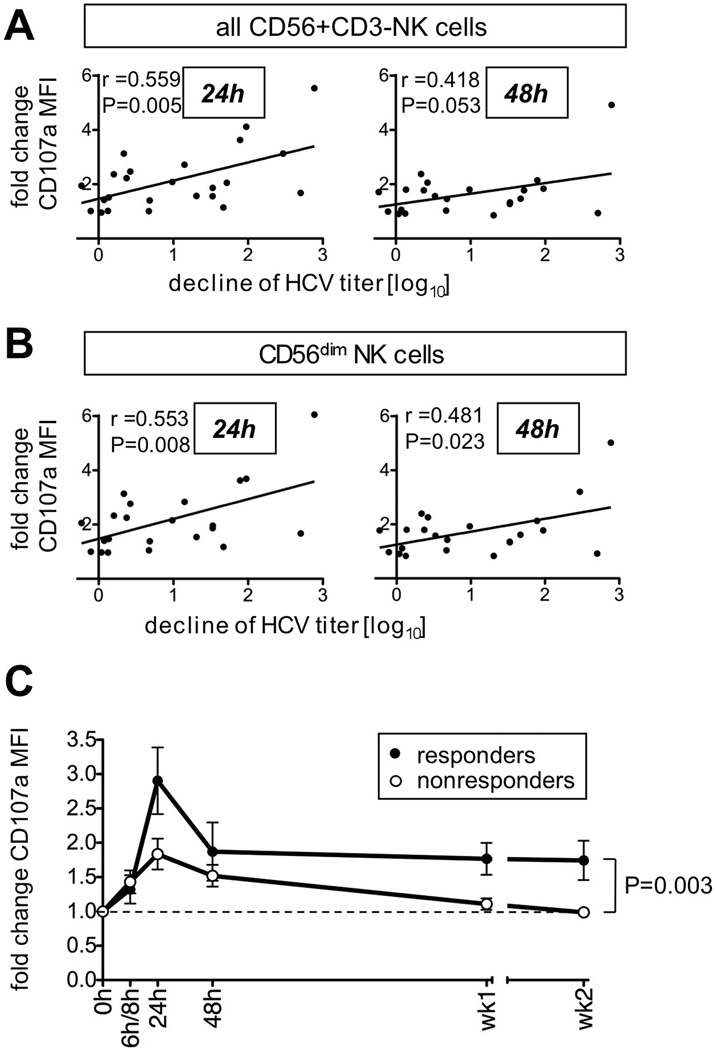

Finally, we investigated a possible relationship between the early NK cell response and the first phase virological response to treatment, which is predictive for a sustained virological response 18. For this purpose we included a group of nonresponders to previous PegIFN/RBV treatment and retreatment 16 that was studied for NK cell responses during the first 2 weeks of PegIFN/RBV re-treatment (Table 1). Interestingly, an early decrease in the frequency of NK cells that express the inhibitory markers NKG2A and SIGLEC7 correlated to the first phase virological response (Table 2, Suppl. Fig. 3). Along this line, induction of NK cell degranulation during the first 24 h (Fig. 5A left graph) and 48 h (Fig. 5A right graph) of therapy also correlated to the first phase virological response. These observations were more pronounced for the CD56dim NK subset (Fig. 5B), which is the more mature, cytotoxic NK cell population. They were preserved when the analysis was restricted to patients with the CC IL28B rs12979860 SNP, and NK cell function did not differ among patient subgroups with IL28B rs12979860 genotypes (not shown).

Table 1.

Epidemiological and clinical data of responder and nonresponder patients*

| responders (n=10) |

non-responders (n=15) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (m/f) | 6/4 | 10/5 |

| Age at start of treatment, median (IQR) years | 54.5 (33–64) | 53 (41–61) |

| Ethnicity (asian / african american / caucasian) | 2/4/4 | 0/2/13 |

| Body mass index, median (IQR) | 33.2 (21.2–40.4) | 27.9 (22.3–31.9) |

| IL-28B rs12979860 SNP (CC/CT/TT) | 6/2/1 | 1/7/3 |

| KIR genotype (2DL2 / 2DL3 / 2DL2, 2DL2 / 2DL3, 2DL3) | 5/10/0/5 | 11/12/3/4 |

| HLA genotype (C1 / C2 / C1C1 / C2C2) | 11/8/2/2 | 11/11/4/4 |

| HCV genotype 1 / genotype 4 | 9/1 | 15/0 |

| HCV RNA titer at start of treatment, | 2.8 × 106 | 2.3 × 106 |

| median (IQR) IU/mL | (13,600-1.5 × 107) | (0.5 × 106 −7.5 × 106) |

| ALT level at start of treatment, median (IQR) U/mL | 79 (29–386) | 58 (25–150) |

| Ishak Inflammatory Score, median (IQR) | 6.5 (4–13) | 7 (5–12) |

| Ishak Fibrosis Score median (IQR) | 1 (0–3) | 2 (0–6) |

as shown in figure 5C

Table 2. Correlation of changes in NK cell phenotype and first phase virological response.

The first phase virological response was correlated to relative changes in the frequency of NKG2A or SIGLEC7-expressing NK cells within the NK cell population and their respective expression level (MFI). Graphs are shown in Suppl. Fig. 3.

| Marker | Time point [h] | MFI | Percentage of NK cells | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson r | P value | Pearson r | P value | ||

| NKG2A | 6 | n.s. | −0.71 | <0.001 | |

| 24 | n.s. | −0.42 | 0.031 | ||

| 48 | n.s. | −0.41 | 0.049 | ||

| SIGLEC7 | 6 | n.s. | n.s. | ||

| 24 | −0.47 | 0.026 | −0.56 | 0.007 | |

| 48 | −0.49 | 0.027 | −0.34 | 0.011 | |

P≤0.05;

P<0.01;

P<0.001;

n.s.: not significant

Figure 5. Degranulation of peripheral blood NK cells correlates to treatment response.

(A–B) Correlation between the 24 h and 48 h change in the CD107a expression on either all blood NK cells (A) or their CD56dim subset (B) and the first phase virological response (log decline in HCV titer during the first 48 h of PegIFN/RBV therapy).

(C) Comparison between CD107a expression on CD56dim NK cells of responders (filled circles, n=10) and nonresponders (open circles, n=15). Mean ± SEM are shown; h, hour; wk, week. The p-value was calculated by ANOVA.

This association between changes in NK cell function and virological response prompted us to compare the kinetics of NK cell degranulation during the first 2 weeks of therapy in responders and nonresponders (Fig. 5C). Consistent with the correlation between NK cell degranulation and first phase virological response, NK cells of nonresponders displayed a significantly smaller increase in NK cell degranulation during the first 24 h of therapy than responders (Fig. 5C). Of note, the increase in NK cell degranulation was sustained in the responders for at least two weeks, whereas it returned to baseline in the nonresponder group by week 1 (p<0.003). Similar results were obtained when NK cells of patients with and without EVR were compared (Suppl. Fig. 4). Collectively, the results demonstrate a correlation between NK cell responsiveness, in particular markers of NK cell cytotoxicity, and treatment response.

Discussion

This study demonstrates a correlation between NK cell responsiveness, specifically the induction of the cytotoxic NK cell function and the first phase (48 h) virological response, as well as the early (12 week) virological response of IFN-α-based therapy.

Peak changes in NK cell phenotype were most pronounced within 6 h after initiation of therapy. In particular, the expression levels of NKp30, NKG2C, SIGLEC7, CD85j and CD69 changed significantly over the course of treatment. In contrast, changes in NKG2A and NKG2D expression were only observed within the first 48 h after interferon injection and lasted less than 1 week. Several observations link these phenotypic changes to the observed increase in NK cell cytotoxicity. For example, NKp30 is one of the natural cytotoxicity receptors and its expression correlates to cytotoxicity 19. NKp30 levels have been shown to be higher on NK cells from HCV-exposed individuals who remain aviremic than in those who become infected, which may indicate an antiviral effect 19. Likewise, expression of the activating receptor NKG2D has been directly correlated to NK cell cytotoxicity, and NKG2D ligands are upregulated in the HCV-infected liver 20. Finally, the observed decrease in expression of the inhibitory receptor NKG2A may indirectly enhance cytotoxic NK cell function because it diminishes signaling in response to HLA-E, which is overexpressed on HCV-infected cells due to stabilization by an endogenously processed HCVcore peptide 21, 22.

The cytotoxic NK cell phenotype was demonstrated by increased degranulation, a higher frequency of TRAIL-expressing NK cells and increased TRAIL expression on NK cells (Fig. 3). TRAIL is an important molecule in the context of hepatitis C because HCV enhances the susceptibility of primary human hepatocytes to TRAIL-mediated killing via increased expression of the death receptors DR4 and DR5 23. This was also demonstrated in vitro with NK cells killing HCV-infected hepatoma cells in a TRAIL-dependent manner 15. TRAIL expression was previously shown to increase during IFN-based therapy of hepatitis C, but its peak was observed at late time points, i.e. weeks 11–13 in that study. Furthermore, a statistical analysis of the treatment-induced NK cell response and the decline in viremia was not performed 15.

Here, we had the opportunity to study NK cell phenotype and function not only at early time points in the blood, but also in the liver. We observed an increase of cytotoxic, i.e. degranulating and TRAIL-expressing NK cells in the blood, which was most pronounced 24 h after treatment initiation (Fig. 3A and B). The significant increase in the size of the intrahepatic cytotoxic CD16+ NK cell subset and the trend of an increase in the percentage and MFI of intrahepatic TRAIL-expressing NK cells 6 h after treatment initiation support this notion (Fig. 4A). The increase in cytotoxic NK cells in the liver may have been caused by either activation of liver-resident NK cells or by recruitment of peripheral blood NK cells. The latter scenario is supported by the decrease in the population of CXCR3+ and CCR5+ NK cells in the blood (Fig. 2). Of note, the peaks of NK cell degranulation and TRAIL production coincided with a small, but significant ALT rise within the first 24 h of therapy. Although serum ALT levels are considered weak correlates of liver injury it should be noted that correlations between ALT levels and NK cell activity have been described in earlier studies on patients with chronic hepatitis C 12, 13, 24.

The observed increase in NK cell cytotoxicity and the decrease in IFN-γ production are also interesting in light of our earlier data on in vitro exposure of NK cells to IFN-α12, and a recent report that IFN-γ production by NK cells is lower in patients with chronic HCV infection than in patients who had successfully been treated 25. Thus, treatment with IFN-α appears to enhance an NK cell phenotype that is already established in chronic HCV infection 12, 13. Exposure to IFN-α may increase signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 1 expression and phosphorylation 26, which results in increased NK cell cytotoxicity and it decreases STAT4 phosphorylation, causing diminished IFN-γ production. A possible compensatory mechanism for the suppression of IFN-γ production might be the observed shift in the NK cell subset proportions towards an increase in the cytokine-producing CD56bright NK cell subset that we observed later during therapy, which is consistent with published literature (Fig. 1C) 15, 22, 25–27.

This study also shows that the immune mechanisms leading to viral clearance differ between spontaneous and treatment-induced resolution of the infection. It is well established that the endogenous type I interferon response does not induce HCV clearance during the natural course of infection (reviewed in 3). Additional immune components, e.g. IFN-γ producing T cells are required for spontaneous HCV clearance. This is consistent with published data that IFN-γ responses of T cells correlate with spontaneous HCV clearance 3.

In contrast, exogenous type I interferon that is used in the treatment protocols at high doses has a strong antiviral effect. NK cells may enhance this antiviral effect and/or may serve as biomarkers of the patients’ interferon responsiveness as suggested by the correlation between early induction of NK cell cytotoxicity and first phase virological response (Fig. 5). While this correlation is relatively weak (r=0.56 for 24h HCV titer decline, r=0.48 for 48h HCV titer decline) it is the earliest indicator of differential NK cell cytotoxicity in IFN-responders and nonresponders and is maintained for the subsequent weeks (Fig. 5C). IFN-γ production appears to be less important, which is consistent with reports that a treatment response is not associated with an increase in the IFN-γ response of HCV-specific T cells (reviewed in 3).

Treatment response is also influenced by genetic factors. While the treatment responder group in figure 5 had a higher percentage of individuals with the IL28B rs12979860 CC SNP (66%) than the nonresponder group (9%; p=0.016), NK cell phenotype and function did not differ among subgroups with different IL28B genotypes, and the correlation between NK cell response and first phase virological response was preserved when restricted to patients with IL28B CC rs12979860 SNP. This is consistent with the fact that lymphocytes do not respond to type III interferons (including IL28B) because they express a short splice variant of the receptor 28. A second genetic component of interest is the KIR/HLA compound haplotype (Table 1, Suppl. Table 1) but we found no difference between patient subgroups. A combined effect of KIR and IL28B in the context of IFN treatment is possible 29 but would require additional studies with a larger number of patients.

These results allow at least two interpretations. First, the NK cell response in the blood may serve as biomarker for interferon responsiveness and complement intrahepatic biomarkers such as the expression level of interferon-induced genes. Second, it is notable that the difference in NK cell responses between responders and nonresponders becomes even more apparent at later time points (Fig. 5C), which may reflect differences in 2nd phase viral decline. Thus, it is conceivable that NK cells become activated early during IFN-based therapy but that NK cell mediated clearance of HCV-infected cells may take longer to occur. Further follow-up is required to evaluate whether these early NK cell responses predict a sustained virological response. If NK cells contribute to virus elimination, targeted enhancement of NK cell function may prove a beneficial option to complement antiviral therapy 30.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Fuh-Mei Duh, Maureen Martin and Mary Carrington, NCI-Frederick for KIR and HLA analysis, and Dr. Xiongce Zhao, NIDDK for statistical advice and data analysis. This study was supported by the NIDDK, NIH intramural research program.

Financial Support: This study was supported by the NIDDK, NIH intramural research program.

Abbreviations

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- EVR

early virological response

- pegIFN

pegylated interferon-alfa

- RBV

ribavirin

- LIL

liver infiltrating lymphocytes

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PBS

phosphate buffer saline

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions: GA, BE, BR designed and analyzed the study. GA, BE, LH, LEH, RT performed experiments. YR, MN, JF, TL wrote the clinical protocol, provided clinical samples and data. All critiqued the manuscript.

Financial Disclosures and Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has any financial arrangements to disclose. No conflicts of interest exist for any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Golo Ahlenstiel, Email: goloahlenstiel@gmail.com.

Birgit Edlich, Email: birgit@edlich-online.com.

Leah J Hogdal, Email: leah.hogdal@gmail.com.

Yaron Rotman, Email: rotmany@niddk.nih.gov.

Mazen Noureddin, Email: noureddinm@niddk.nih.gov.

Jordan J Feld, Email: jordan.feld@uhn.on.ca.

Lauren E Holz, Email: holzle@niddk.nih.gov.

Rachel H Titerence, Email: rachel.titerence@gmail.com.

T Jake Liang, Email: JakeL@bdg10.niddk.nih.gov.

Barbara Rehermann, Email: Rehermann@nih.gov.

References

- 1.Ciesek S, Manns MP. Hepatitis in 2010: The dawn of a new era in HCV therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:69–71. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Layden TJ, Mika B, Wiley TE. Hepatitis C kinetics: mathematical modeling of viral response to therapy. Semin Liver Dis. 2000;20:173–183. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rehermann B. Hepatitis C virus versus innate and adaptive immune responses: a tale of coevolution and coexistence. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1745–1754. doi: 10.1172/JCI39133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norris S, Collins C, Doherty DG, Smith F, McEntee G, Traynor O, Nolan N, Hegarty J, O'Farrelly C. Resident human hepatic lymphocytes are phenotypically different from circulating lymphocytes. J Hepatol. 1998;28:84–90. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80206-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biron CA, Nguyen KB, Pien GC, Cousens LP, Salazar-Mather TP. Natural killer cells in antiviral defense: function and regulation by innate cytokines. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:189–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khakoo SI, Thio CL, Martin MP, Brooks CR, Gao X, Astemborski J, Cheng J, Goedert JJ, Vlahov D, Hilgartner M, Cox S, Little AM, Alexander GJ, Cramp ME, O'Brien SJ, Rosenberg WM, Thomas DL, Carrington M. HLA and NK cell inhibitory receptor genes in resolving hepatitis C virus infection. Science. 2004;305:872–874. doi: 10.1126/science.1097670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knapp S, Warshow U, Hegazy D, Brackenbury L, Guha IN, Fowell A, Little AM, Alexander GJ, Rosenberg WM, Cramp ME, Khakoo SI. Consistent beneficial effects of killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor 2DL3 and group 1 human leukocyte antigen-C following exposure to hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2010;51:1168–1175. doi: 10.1002/hep.23477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Turner SC, Chen KS, Ghaheri BA, Ghayur T, Carson WE, Caligiuri MA. Human natural killer cells: a unique innate immunoregulatory role for the CD56(bright) subset. Blood. 2001;97:3146–3151. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fauriat C, Long EO, Ljunggren HG, Bryceson YT. Regulation of human NK-cell cytokine and chemokine production by target cell recognition. Blood. 2010;115:2167–2176. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-238469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Maria A, Bozzano F, Cantoni C, Moretta L. Revisiting human natural killer cell subset function revealed cytolytic CD56(dim)CD16+ NK cells as rapid producers of abundant IFN-gamma on activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:728–732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012356108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Maria A, Fogli M, Mazza S, Basso M, Picciotto A, Costa P, Congia S, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Increased natural cytotoxicity receptor expression and relevant IL-10 production in NK cells from chronically infected viremic HCV patients. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:445–455. doi: 10.1002/eji.200635989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahlenstiel G, Titerence RH, Koh C, Edlich B, Feld JJ, Rotman Y, Ghany MG, Hoofnagle JH, Liang TJ, Heller T, Rehermann B. Natural killer cells are polarized toward cytotoxicity in chronic hepatitis C in an interferon-alfa-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:325–335. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliviero B, Varchetta S, Paudice E, Michelone G, Zaramella M, Mavilio D, De Filippi F, Bruno S, Mondelli MU. Natural killer cell functional dichotomy in chronic hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis C virus infections. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1151–1160. 1160, e1–e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunn C, Brunetto M, Reynolds G, Christophides T, Kennedy PT, Lampertico P, Das A, Lopes AR, Borrow P, Williams K, Humphreys E, Afford S, Adams DH, Bertoletti A, Maini MK. Cytokines induced during chronic hepatitis B virus infection promote a pathway for NK cell-mediated liver damage. J Exp Med. 2007;204:667–680. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stegmann KA, Bjorkstrom NK, Veber H, Ciesek S, Riese P, Wiegand J, Hadem J, Suneetha PV, Jaroszewicz J, Wang C, Schlaphoff V, Fytili P, Cornberg M, Manns MP, Geffers R, Pietschmann T, Guzman CA, Ljunggren HG, Wedemeyer H. Interferon-alpha-induced TRAIL on natural killer cells is associated with control of hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1885–1897. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feld JJ, Modi AA, El-Diwany R, Rotman Y, Thomas E, Ahlenstiel G, Titerence R, Koh C, Cherepanov V, Heller T, Ghany MG, Park Y, Hoofnagle JH, Liang TJ. S-Adenosyl Methionine Improves Early Viral Responses and Interferon-Stimulated Gene Induction in Hepatitis C Nonresponders. Gastroenterology. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahlenstiel G, Martin MP, Gao X, Carrington M, Rehermann B. Distinct KIR/HLA compound genotypes affect the kinetics of human antiviral natural killer cell responses. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1017–1026. doi: 10.1172/JCI32400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parruti G, Polilli E, Sozio F, Cento V, Pieri A, Di Masi F, Mercurio F, Tontodonati M, Mazzotta E, Ceccherini-Silberstein F, Manzoli L, Perno CF. Rapid prediction of sustained virological response in patients chronically infected with HCV by evaluation of RNA decay 48h after the start of treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin. Antiviral Res. 2010;88:124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golden-Mason L, Cox AL, Randall JA, Cheng L, Rosen HR. Increased natural killer cell cytotoxicity and NKp30 expression protects against hepatitis C virus infection in high-risk individuals and inhibits replication in vitro. Hepatology. 2010;52:1581–1589. doi: 10.1002/hep.23896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sene D, Levasseur F, Abel M, Lambert M, Camous X, Hernandez C, Pene V, Rosenberg AR, Jouvin-Marche E, Marche PN, Cacoub P, Caillat-Zucman S. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) evades NKG2D-dependent NK cell responses through NS5A-mediated imbalance of inflammatory cytokines. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001184. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nattermann J, Nisschalke HD, Hofmeister V, Ahlenstiel G, Zimmermann H, Leifeld H, Weiss EH, Sauerbruch T, Spengler U. The HLA-A2 restricted T cell epitope HCV core 35–44 stabilizes HLA-E expression and inhibits cytolysis mediated by natural killer cells. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:443–453. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62267-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrison RJ, Ettorre A, Little AM, Khakoo SI. Association of NKG2A with treatment for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;161:306–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04169.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lan L, Gorke S, Rau SJ, Zeisel MB, Hildt E, Himmelsbach K, Carvajal-Yepes M, Huber R, Wakita T, Schmitt-Graeff A, Royer C, Blum HE, Fischer R, Baumert TF. Hepatitis C virus infection sensitizes human hepatocytes to TRAIL-induced apoptosis in a caspase 9-dependent manner. J Immunol. 2008;181:4926–4935. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonorino P, Ramzan M, Camous X, Dufeu-Duchesne T, Thelu MA, Sturm N, Dariz A, Guillermet C, Pernollet M, Zarski JP, Marche PN, Leroy V, Jouvin-Marche E. Fine characterization of intrahepatic NK cells expressing natural killer receptors in chronic hepatitis B and C. J Hepatol. 51:458–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.05.030. 2--9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dessouki O, Kamiya Y, Nagahama H, Tanaka M, Suzu S, Sasaki Y, Okada S. Chronic hepatitis C viral infection reduces NK cell frequency and suppresses cytokine secretion: Reversion by anti-viral treatment. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;393:331–337. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyagi T, Takehara T, Nishio K, Shimizu S, Kohga K, Li W, Tatsumi T, Hiramatsu N, Kanto T, Hayashi N. Altered interferon-alpha-signaling in natural killer cells from patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2010;53:424–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee S, Watson MW, Flexman JP, Cheng W, Hammond T, Price P. Increased proportion of the CD56(bright) NK cell subset in patients chronically infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) receiving interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. J Med Virol. 2010;82:568–574. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Witte K, Gruetz G, Volk HD, Looman AC, Asadullah K, Sterry W, Sabat R, Wolk K. Despite IFN-lambda receptor expression, blood immune cells, but not keratinocytes or melanocytes, have an impaired response to type III interferons: implications for therapeutic applications of these cytokines. Genes Immun. 2009;10:702–714. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dring MM, Morrison MH, McSharry BP, Guinan KJ, Hagan R, O'Farrelly C, Gardiner CM. Innate immune genes synergize to predict increased risk of chronic disease in hepatitis C virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:5736–5741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016358108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vivier E, Raulet DH, Moretta A, Caligiuri MA, Zitvogel L, Lanier LL, Yokoyama WM, Ugolini S. Innate or Adaptive Immunity? The Example of Natural Killer Cells. Science. 2011;331:44–49. doi: 10.1126/science.1198687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.