Abstract

Although the quality and effectiveness of mental health treatments and services have improved greatly over the past 50 years, therapeutic revolutions in psychiatry have not yet been able to reduce stigma. Stigma is a risk factor leading to negative mental health outcomes. It is responsible for treatment seeking delays and reduces the likelihood that a mentally ill patient will receive adequate care. It is evident that delay due to stigma can have devastating consequences. This review will discuss the causes and consequences of stigma related to mental illness.

Keywords: Barriers, Compliance, Intervention, Psychosis, Schizophrenia, Stigma, Treatment

Introduction

Although the quality and effectiveness of mental health treatments and services have improved greatly over the past 50 years, therapeutic revolutions in psychiatry have not yet been able to reduce stigma. Stigma is universally experienced, isolates people and delays treatment of mental illness, which in turn causes great social and economic burden.

A study from India showed that the duration of untreated illness from first psychotic illness to neuroleptic treatment in schizophrenia was 796 weeks (Tirupati et al., 2004[57]).

And, lest some feel this is so only in India, let it be noted that this is the reality at many other places all over the world.

Individuals with mental illnesses are stigmatised. Many people who might benefit from these services do not obtain them, or do not fully adhere to treatment regimens once they have begun. Treatment adherence plays a vital role in psychiatric rehabilitation (Tsang et al., 2006[58]). Unfortunately, poor adherence to medication and psychosocial treatment is prevalent among individuals with schizophrenia, which increases their likelihood of relapse and re-hospitalisation (Swanson et al., 1997[53]; Tay, 2007[54]; McCann et al., 2008[30]).

If stigma is one factor that delays treatment seeking and continuation, then specific measures to reduce stigma in a variety of mental illnesses may prove to be of great value to achieve better outcomes. This will also allow for better patient integration into society as social barriers due to prejudice are reduced. However, integrating stigma coping strategies in treatment in routine clinical practice remains a challenge.

Continued stigma is likely to cause severe direct disability and indirect economic implications. Reducing stigma may represent a cost-effective way to reduce the risk of relapse and poor outcome occasioned by chronic exposure to stigmatising environments. In addition, significant gains in quality of life may result if all patients with schizophrenia routinely receive information about stigma and are taught to use simple strategies to increase resilience vis-à-vis adverse, stigmatising environments. Clearly, more work needs to be done to identify interventions that will deal with barriers to treatment and thereby enhance quality of life of individuals suffering from mental illnesses.

In this review we first discuss the presence and experience of stigma due to mental illness by patients and relatives, and the pathways through which stigma influences the lives of patients.

We propose and discuss client-centric interventions for dealing with stigma at an individual level (patient). We further argue that assessment of stigma needs to move to the clinics of mental health professionals.

What Causes Stigma?

Stigma was exacerbated by the 19th-century separation of the mental health treatment system from the mainstream of healthcare. However, stigma originates from multiple sources, which work in a synergistic manner and have serious implications on an individual's life. We believe it may originate from personal, social and family sources, and from the nature of the illness itself (Wig, 1997[61]). Several studies show that stigma usually arises from lack of awareness, lack of education, lack of perception, and the nature and complications of the mental illness, for example odd behaviours and violence (Arboleda-Florez, 2002[5]).

Stigma related to schizophrenia in India is particularly high (Thara et al., 2000[55]). Stigma and discrimination linked to schizophrenia was found to have a significant impact on the lives of these individuals from a study investigating patient's perceptions of stigma. It was reported that with respect to perceived causes of stigma, a strikingly large percentage of participants (97%) believed that stigma was caused by a lack of awareness about schizophrenia, followed by the nature of the illness itself (73%). Behavioural symptoms associated with schizophrenia were also thought to cause stigma, whereas drug-related complications were seen as playing a less influential role in stigma. Sixty nine percent of patients feel that stigma comes from attitudes from the general community, 46% from co-workers and 42% from family members (Shrivastava et al., 2011[46]).

Causes and consequences of stigma are often indistinguishable and lead to prejudices that influence attitudes, which in turn increase prejudices perpetually. In that context, self-stigma and perceived stigma both contribute significantly to consequences which include changes in familial and societal attitudes. Most of the impact of stigma can be explained by the concept of self-stigma and perceived stigma, where self-stigma is defined as areas of stigma, which can be categorized as personal, social, familial, medical, and treatments of illness. Perceived stigma, on the other hand, refers to how individuals perceive stigma which influences their coping style (Byrne, 2001[8]; Reader et al., 2008[40]). This is probably why consequences of stigma are individualized.

A major source of stigma is recognized as originating from public sources such as employers. In a large interview-based study, Loganathan and Murthy (2008[28]) attempted to identify the origins of stigma using specific questions and concluded that stigma and discrimination were mostly experienced during the acute phase of the illness because of socially unacceptable behaviour. These findings are consistent with those of Penn et al., 1994[35], who reported that knowledge of acute phase of psychosis induced greater stigma. Those individuals who had no previous contact perceived the mentally ill as dangerous and tended to avoid them. In general, knowledge of symptoms associated with the acute phase of schizophrenia was more responsible for stigma than the label of schizophrenia alone. Of interest was Dube's (1970[10]) report that it was socially unacceptable behaviour which was more responsible for stigma compared to supernatural influence. In contrast, more information about the target individual's post-treatment living arrangements (i.e., supervised care) reduced negative judgments.

Several studies have shown that public stereotypes and prejudice about mental illness have a deleterious impact on obtaining and keeping good jobs (Bordieri et al., 1986[6]; Link, 1982[26], 1987[27]; Wahl, 1999[60]) and leasing safe housing (Segal et al., 1980[45]; Wahl, 1999[60]). Stigma also arises due to prejudice in the criminal justice system. Criminalizing mental illness occurs when police, rather than the mental health system, responds to mental health crises, thereby contributing to the increasing prevalence of people with serious mental illness in jail. The growing intolerance to forensic issues of mental health, and human right movement in general, has led to harsher laws, and has hampered effective treatment planning for mentally ill offenders (Jemelka et al., 1989[17]).

Poverty and Stigma

Despite overall global socio-economic development and improved social capital large part of this planet continues to be deprived. Poverty is one of the determinants of mental illnesses and social exclusion perpetuates deprivation.

Millions of people living in the third world are still not ‘free’, “…denied elementary freedom and… imprisoned in one way or another by economic poverty, social deprivation, political tyranny, or cultural authoritarianism” (Singh and Singh, 2008[47]).

A review by Patel et al., 2003[34] of English-language journals published since 1990 and three global mental health reports identified 11 community directed studies on the association between poverty and common mental disorders in six low- and middle-income countries. Most studies showed an association between indicators of poverty and the risk of mental disorders, the most consistent association being with low levels of education. It is difficult to identify the mechanism behind this association. The possibility of increased stress from social factors associated with poverty or the impoverished nutritional state may be causal in part. A study by Jung (2008[18]) examined the association of perceived stigma and poverty in a study of 1139 respondents. Overall, perceived stigma of socio-economic status was associated negatively with life satisfaction and positively with psychological distress after controlling for other predictors. There are also ethnic variations, suggesting that among blacks, race stigma was not associated with life satisfaction and psychological distress as opposed to stigma of socio-economic status. Among whites, perceived stigma of socio-economic status was not related to life satisfaction and psychological distress (Jung, 2008[18]).

Stigma Across Psychiatric Diagnoses

Despite the fact that stigma is universal the question remains as to whether or not the nature and consequences of stigma are similar across all psychiatric illnesses. Interestingly, there is no clear evidence that perceived or self stigma varies across diagnosis as few studies have investigated this issue. In general stigma is reported to be associated with illness that manifests with behavioural disturbances or socially odd behaviour.

In one study two hundred university students completed scales measuring their beliefs about either depression or schizophrenia. Specifically they measured their perceptions of relevant social norms and their preferred level of social distance to someone with schizophrenia or depression. Measures of social desirability bias were also completed. The study highlighted that the proportion of variance in preferred social distance was approximately doubled when perceived norms were added to beliefs about illness in a regression equation. Perceived social norms are an important contributor to an individual's social distance to those with mental illness. Messages designed to influence perceived social norms might help reduce stigmatisation of the mentally ill (Norman et al., 2008[33]; Norman et al., 2010[32]).

The relationships of stigma to both depression and somatisation were studied in another study in South India to test the hypothesis that stigma is positively related to depressive symptoms and negatively related to somatoform symptoms in 80 psychiatric outpatients. The tendency to perceive and report distress in psychological or somatic terms is influenced by various social and cultural factors, including the degree of stigma associated with particular symptoms. This study with the Explanatory Model Interview Catalogue demonstrates how quantitative and qualitative methods can be effectively combined to examine key issues in cultural psychiatry (Raguram et al., 1998[38]).

Consequences of Stigma

A family whose son died was caring for his widow who happened to be schizophrenic.

Several treatment attempts were made to arrest the illness without success. Consequently, the daughter-in-law's behaviors were uncontrolled causing a number of problems. The patient's in-laws were unable to cope and finally sent her by train on a pilgrimage to Rishikesh in Uttarakhand state without the possibility of return. (Agarwal, 1998[3])

Consequences of stigma can be life threatening and humiliating. It can deprive an individual from basic needs, marginalize and deprive them, potentially leading to their death by self-neglect or suicide. More than 40% of countries have no mental health policy, and over 30% have no mental health programmes. Existing health plans frequently do not cover mental and behavioural disorders at the same level as other illnesses, creating significant economic difficulties for patients and their families. One of the identified reasons for low support for mental health is the stigma attached to mentally ill individuals (World Health Report, 2001[62]). Being mentally ill is still considered a shameful condition that causes the person or the family to lose face. In some cultures, to have a mentally ill relative could, by association, damage the possibilities of advancement of other family members, to an extent where it might harm the marriage prospects of a young daughter or sister.

It is important to understand that the nature, determinants and consequences of stigma vary across culture and region. For instance, according to a study by Murthy (2005[31]), urban respondents in large centres try to hide their illness hoping to remain unnoticed, whereas rural respondents in smaller regions experience greater ridicule, shame and discrimination, as anonymity is more difficult. Also, Jadhav et al. (2007[16]) reported that rural Indians showed significantly higher stigma scores, especially those patients with a manual occupation. Urban Indians showed a strong link between stigma and not wishing to work with a mentally ill individual, whereas no such link existed for rural Indians. A study by Switaj et al. (2009[52]), reported reduced life satisfaction as a key aspect of the subjective experience of stigma. This cross-sectional study assessed the extent of stigma experienced by patients with schizophrenia to establish its clinical and socio-demographic predictors. The experience of stigmatisation was common among respondents who most frequently reported having concealed their illness (86%), witnessed others saying offensive things about the mentally ill (69%), were worried about being viewed unfavourably (63%) and treated as less competent (59%). Higher levels of stigma were related to lower subjective quality of life and younger age of illness onset. No significant associations were found between stigma and symptoms or level of social functioning.

Several studies have shown that patients feel rejection from family members. People with mental illness experience stigma during the course of their illness and treatment, and it is an important predictor for the relapse of symptoms and non-compliance to treatment. Despite experiencing stigma, one study showed that the majority experienced stigma in the form of lowered self-esteem (69%), which may be the result of their knowledge of the prejudices held by society, or from specific events. In this study many individuals also reported being ignored because of their illness, and overhearing offensive comments about mental illness (46%) (Adhikari et al., 2008[2]).

A 40 year old man who was treated for schizophrenia managed to find work. While going to the doctor he was seen by other patients who made him feel uncomfortable and ashamed. However, medications could only be dispensed from a doctor's clinic forcing him to continue the same routine that he found so humiliating. Nevertheless, he managed to circumvent the clinic by getting his medication from a local medical shop. This practice continued for three to four years. Unfortunately, he developed obvious tremors of the right hand that were visible to his coworkers. They then began to make fun of him, equating his condition to that of an old man. Specifically, they would tease him by saying he had Parkinson's disease. Consequently, he found it very difficult to manage serving tea in the office and as a result lost his job. (Principal Author's experience in practice).

Stigmatisation of the mentally ill leads to the selective isolation of people, whom society considers either physically flawed or behaviourally odd (Rinnerthaler et al., 200668); Martin et al., 2000[29]). Stigmatisation also deprives individuals with mental illnesses their full measure of human dignity and the opportunity to participate in society (Lauber et al., 2004[23]). Consequently, the discrimination resulting from stigma leads to compromised social support and opportunities for treatment by individuals and institutions (Martin et al., 2000[29]; Thornton et al, 1996[56]). Negative attitudes exist not only amongst the members of society but also amongst health professionals (Read et al., 199966). Stigmatization represents a chronic negative interaction with the environment that most people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia face on a regular basis.

The question that arises is why do people with mental health problems fail to engage in treatment (Goff et al., 2010[13]; Franz et al., 2010[12]; AbuMadini et al., 2002[1])? Many among the general public assume that persons with psychotic disorders are unpredictable and incapable of being managed, even by the best efforts of the health care system, and therefore are considered a threat to the social order and to public safety (Kelly, 2005[20]; Appelbaum et al., 2000[4]). Society encourages and reinforces stigmatization through a host of mechanisms, e.g. public print and film media. In a Nigerian study, the most common descriptions reported were derogatory terms (33%). This was followed by abnormal appearance and behaviour (29.6%); physical illness and disability (13.6%), negative emotional states (6.8%), and language and communication difficulties (3.4%). The results suggest that, similar to findings elsewhere, stigmatization of mental illness is highly prevalent among Nigerian children (Ronzoni et al., 2010[42]). Similarly, a Chinese study from Hong Kong examined the experience of stigma associated with psychiatric treatment for schizophrenia. In focus groups patients described stigma experiences related to clinic visits and the side effects of antipsychotic medications. Results showed that patients with schizophrenia were more likely to anticipate stigma, conceal illness, and default on clinic visits, than patients with diabetes. Medication-induced stigma occurred in 48% of patients with schizophrenia. It brought about the unwelcome disclosure of illness, workplace difficulties, family rejection and treatment non-adherence. Adverse experiences during hospitalization were also reported by 44% of patients with schizophrenia (Lee et al., 2006[24]).

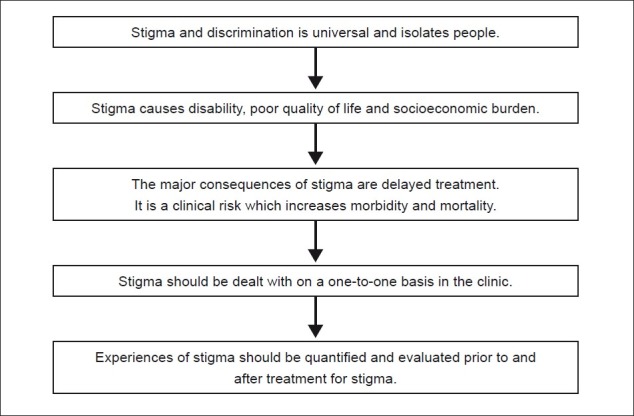

The consequences of psychiatric stigma are fairly consistent across communities. They include negative labelling, discrimination, treatment avoidance, such menacing societal responses as ostracism and exclusion, and even violence and suicide. The original impact of stigma leads to discrimination which further increases discrimination, forming a vicious cycle [Figure 1]. In non-Western communities, and in developing countries, psychiatric stigma is particularly severe. It is possibly due to ignorance and poor availability of care (Lee, 2002[25]). The origin of psychiatric stigma is complex but research on the subject has frequently focussed on negative public attitudes (Schulze et al., 2003[44]; Stuart et al., 2001[51]). Mental illness is usually concealable. People who hold negative attitudes may not demonstrate discriminatory behaviour toward people who suffer from mental illness (Pinel, 1999[36]). Common effects of stigma are low self-esteem and discrimination in family and work settings. Providing care and treatment are identified as the most common method of combating stigma.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of paper

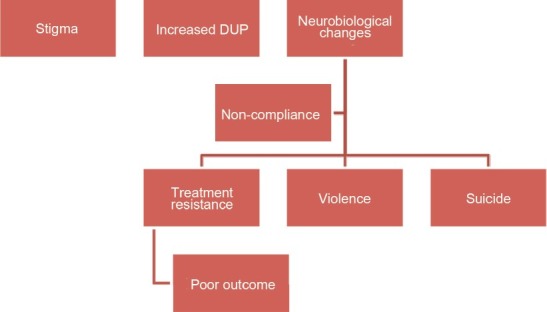

Stigma: A Clinical Risk

Stigma is a risk factor leading to negative mental health outcomes. This is particularly true in schizophrenia and related psychosis. It is responsible for treatment seeking delays and reduces the likelihood that a mentally ill patient will adhere to treatment, which inadvertently increases the probability of violent behaviours and suicide attempts [Figure 2]. These displays understandably exacerbate the problem of social isolation (Martin et al., 2000[29]). Stigma can prolong the duration of untreated illness and in turn perpetuate the neurotoxic effects of psychosis, leading to profound disability [Figure 1].

Figure 2.

This shows the consequences of stigma and neurobiological changes for outcome.

Research shows that early intervention in psychosis is not only protective but has the potential to arrest, or at least delay, deterioration and relapse. It also facilitates good outcome and quality of life. Thus, an important goal for ensuring effective intervention as early as possible is identifying and reducing stigma. Unfortunately, the clinical impact of stigma remains a low priority in research (King et al., 2007[21]; Carpenter, 2009[9]). One of the key requirements for success of early intervention programmes is to formulate anti-stigma measures. The lack of awareness alone is not responsible for keeping patients away from treatment: it is the fear of being labelled as mentally ill. Families know that mental illness is an ‘illness′, but prejudice and shame interfere not only in seeking treatment but also in its continuation (Sirey et al., 2001a[48]; Sirey et al., 2001b[49]; Gray, 2002[14]).

A 45 year old female schizophrenic was living with her brother and his wife since her parents were no longer alive; she had no other relatives, and no financial resources or outside social support. Her condition was such that it was not possible to leave her alone at home because of her predisposition to aggression and rage. She also had a comorbid personality disorder, which would manifest during her aggressive episodes. To make matters worse, her brother and his wife beat her regularly. Out of frustration, she attempted suicide four times. She was later placed in a long-term rehabilitation centre with financial support from a charitable organization. (Principal author's experience in practice).

Undoubtedly, stigma remains a potential ‘risk factor’ for mental illness. It is therefore important to address the issue of stigma at the individual patient level to achieve high retention rates in the programme. The response to reducing stigma is frustratingly lacking due to a number of reasons:

The medical or genetic explanations of serious mental illness implementing biology reinforce stigma, because of the public perception that little can be done about mental illnesses (Martin et al., 2000[29]; Gray, 2002[14]; Read, 1999[39]).

There is a tendency among professionals to assume that mental health literacy will automatically improve with increasing advancements in research, leading to stigma reduction. However, this kind of a direct correlation does not exist and presents limitations concerning more innovative experiments on topics other than that of “possible increase in the risk for the patient”(Lauber, 2004[23]).

Care providers have shown that treatment adherence for stigmatised persons with mental health problems is compromised. This is in part because of misinterpretations of the biological factors in mental disorders, which in turn dampens their hopes that medical treatment could be helpful. Perhaps this is why these patients pursue non-scientific practices such as ‘faith based healing’ (Gray, 2002[14]).

Contradictory opinions have been expressed for early intervention in relation to stigma. It is well documented that dealing with stigma can facilitate early intervention and that early intervention can in turn reduce stigma (Filaković et al ., 2007[11]). Separate from stigmatisation, there is the possibility that early psychopharmacological interventions using antipsychotics may have an effect on the developing brain (Carpenter, 2009[12]). It is not surprising then that ethical questions are raised when medicating and labelling adolescents (Filaković et al ., 2007[11]). These examples and concerns suggest that treatment centres may, in spite of themselves, promote stigma. If this is true, professionals may be perpetrators of prejudice. All of the above are significant barriers that may prevent proper care and make it difficult to bring assessment of stigma into the clinic (Large et al., 2011[22]).

Experiences of mental illness stigma, prejudice, and discrimination can be classified into three possible dimensions: 1) perceived stigma (how the individual believes they are viewed by society); 2) experienced stigma (instances of discrimination) and; 3) self-stigma (internalisation of public stigma) (Brohan et al., 2010[7]). Measures used to assess stigma can also be classified into the above categories, and one study reported that in the past ten years of stigma research, 79% of them used a measure of perceived stigma, 46% measures of experienced stigma, and 33% measures of self-stigma (Brohan et al., 2010[7]).

Several dimensions of mental illness have been reported to be directly related to stigma. A study by Staring et al. (2009[50]) demonstrated that the associations between insight into one's illness and depression, low quality of life, and negative self-esteem were moderated by stigma. Patients who had good insight and who also did not perceive much stigmatization appeared to do best on use of various outcome parameters, while those with poor insight were found to have problems with service engagement and medication compliance. On the other hand, patients with good insight accompanied by stigmatising beliefs were at the highest risk of negative self-esteem, low quality of life, and depressed mood (Staring et al., 2009[50]) This research suggests that attempts to increase patients’ insight into their illness is not enough as perceptions of stigma must also be addressed.

The stigma of being mentally ill and the need for treatment or hospitalisation are serious psychological strains (Karow, 2006[19]). The adverse effects of these social, economic and societal factors, along with the social stigma of mental illness, constitute a form of ‘structural violence’ that impairs access to psychiatric and social services, and amplifies the effects of schizophrenia in the lives of sufferers (Kelly, 2005[20]). The most common patient-reported barriers are the stigma associated with taking medications, adverse drug reactions, forgetfulness, and lack of social support (Hudson et al., 2004[15]; Goff et al., 2010[13]). Psycho-educational programs have been proposed to reduce the social stigma and societal intolerance to mental patients. Active family involvement improves compliance and might reduce re-hospitalisation rates. Stigma also increases the number and duration of hospitalisations in long-term stay facilities (AbuMadini et al., 2002[1]). Also, stigma is correlated with beliefs about mental illness. A study by Pyne et al. (2001[37]) found that younger age, fewer depressive symptoms, lower perceived medication efficacy, greater satisfaction with current mental health, and less concern about mental illness stigma, were associated with not believing one was mentally ill (Pyne et al., 2001[37]).

There is enough evidence to suggest that stigma is a clinical condition; it is related to the phenomenology and symptom constellation of an illness. However, it remains poorly understood, investigated, and treated. To address the issue of stigma in the treatment setting is necessary and likely to offer the best possible anti-stigma program at an individual level. In order to achieve this goal, it needs to be demonstrated whether or not mental illness stigma can be quantified, and whether such quantification can help clinicians in dealing with stigma.

Concluding Remarks [See also Figure 1: Flowchart of Paper]

It is clear that stigma leads to negative outcomes for those with mental illnesses. Specifically, it means because of it, the mentally ill avoid seeking treatment because they fear being discovered and in turn shunned from society. Consequently, they increase their duration of untreated illness (DUI), continue to experience debilitating symptoms and as a result face the very stigma they were attempting to avoid in the first place [Figure 1].

In increasing their DUI they reduce their chances of managing their illness successfully. We must implement ways of managing stigma or more realistically the perception of the stigmatising events in order to increase the probability of seeking treatment (See part two in this paper).

Take home message

Stigma is universal.

Stigma causes discrimination and isolates people.

Stigma is especially felt by those with mental illnesses.

Stigma is poorly understood and needs to be investigated further.

Stigma increases duration of untreated illness.

Stigma needs to be addresses for individual clients.

Questions that this Paper Raises

What are the clinical consequences of stigma?

Can stigma lead to increased duration of illness?

Does stigma have an impact of quality of life?

How is socio-economic status associated with stigma?

Would dealing with stigma on an individual basis be beneficial?

About the Author

Amresh Shrivastava, MD, MRCPsych, trained at KEM hospital in Mumbai. He worked as a consultant psychiatrist and was a Founding Director of PRERANA Charitable Trust for Suicide prevention in Mumbai, India He is Secretary of the Psychoendocrinology section of the “World Psychiatric Association” and works in the field of International mental health. Dr. Shrivastava's teaching and research interest are related to suicide behaviour and schizophrenia, particularly early psychosis, at-risk candidates and outcome measures. Currently he is the Physician Lead, Early Intervention Program, Regional Mental Health Care, St.Thomas; Associate Professor of psychiatry, The University of Western Ontario; and Associate Scientist, Lawson Health Research Centre, London, Ontario, Canada

About the Author

Megan Johnston, MA, is currently a PhD Candidate in Psychology at the University of Toronto in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Her primary research interests involve parental and socialization influences on moral development and antisocial and prosocial behaviour in adolescence. She is also affiliated with Regional Mental Health Care - St. Thomas, Ontario, Canada, where her research focuses on the social and clinical outcomes of schizophrenia and suicide risk assessment and prevention

About the Author

Yves Bureau, PhD, earned a degree in neuroscience (1991), an MSc in biology (1994) and a PhD in the area of experimental psychology (2001). He completed two post- doctoral fellowships, one at Merck Frosst Canada and Company in Kirkland Québec specializing in Neuropharmacology (2002), and the other at the Lawson Health Research Institute in London, Ontario, specializing in Neuroimaging (2004). He is presently a professor in the psychology and the medical biophysics departments at The University of Western Ontario. He is also an associate scientist at the Lawson Health Research Institute and the director of Inferential Statistics for the Imaging division. Currently his research interests are in the areas of behavioural neuroscience and psychiatry

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared

Declaration

This is our original unpublished work, not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

CITATION: Shrivastava A, Johnston M, Bureau Y. Stigma of Mental Illness-1: Clinical Reflections. Mens Sana Monogr 2012; 10: 70-84.

References

- 1.AbuMadini MS, Rahim SI. Psychiatric admission in a general hospital: Patients profile and patterns of service utilization over a decade. Saudi Med J. 2002;23:44–50. PMID: 11938363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adhikari SR, Pradhan SN, Sharma SC. Experiencing stigma: Nepalese perspectives. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2008;6:458–65. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v6i4.1736. PMID: 19483426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal AK. The forgotten millions. Indian J Psychiatry. 1998;40:103–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appelbaum PS, Robbins PC, Monahan J. Violence and delusions: Data from the MacArthur violence risk assessment study. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:566–72. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.566. PMID: 10739415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arboleda-Florez J. What causes stigma? World Psychiatry. 2002;1:25–6. PMID: 16946812. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bordieri J, Drehmer D. Hiring decisions for disabled workers: Looking at the cause. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1986;16:197–208. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brohan E, Slade M, Clement S, Thornicroft G. Experiences of mental illness stigma, prejudice and discrimination: A review of measures. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:80. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-80. PMID: 20338040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrne P. Psychiatric stigma. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:281–4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carpenter WT. Anticipating DSM-V: Should psychosis risk become a diagnostic class? Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:894–908. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp071. PMID: 19633215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dube KC. A study of prevalence and biosocial variables in mental illness in a rural and urban community in Uttar Pradesh, India. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1970;46:327–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1970.tb02124.x. PMID: 5502780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filaković P, Degmecić D, Koić E, Benić D. Ethics of the early intervention in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Danub. 2007;19:209–15. PMID: 17914322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franz L, Carter T, Leiner AS, Bergner E, Thompson NJ, Compton MT. Stigma and treatment delay in first-episode psychosis: A grounded theory study. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2010;4:47–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2009.00155.x. PMID: 20199480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goff DC, Hill M, Freudenreich O. Strategies for improving treatment adherence in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:20–6. doi: 10.4088/JCP.9096su1cc.04. PMID: 21190649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray A. Stigma in psychiatry. J R Soc Med. 2002;95:72–6. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.95.2.72. PMID: 11823548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hudson TJ, Owen RR, Thrush CR, Han X, Pyne JM, Thapa P, Sullivan G. A pilot study of barriers to medication adherence in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:211–16. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0211. PMID: 18312040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jadhav S, Littlewood R, Ryder AG, Chakraborty A, Jain S, Barua M. Stigmatization of severe mental illness in India: Against the simple industrialization hypothesis. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:189–94. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.37320. PMID: 20661385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jemelka R, Trupin E, Chiles JA. The mentally ill in prisons: a review. Hosp Commun Psychiatry. 1989;40:481–91. doi: 10.1176/ps.40.5.481. PMID: 2656483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung H. Stigma of disadvantaged socio-economic status and its effect on life satisfaction and psychological distress. SSWR. 2008. [accessed on 2011 Oct 30]. Available from: http://sswr.confex.com/sswr/2008/techprogram/P9124.HTM .

- 19.Karow A, Pajonk FG. Insight and quality of life in schizophrenia: Recent findings and treatment implications. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19:637–41. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000245754.21621.c9. PMID: 17012945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly BD. Structural violence and schizophrenia. Soc Sc Med. 2005;61:721–30. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.020. PMID: 15899329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King M, Dinos S, Shaw J, Watson R, Stevens S, Passetti F, et al. The stigma scale: Development of a standardized measure of the stigma of mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:248–54. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.024638. PMID: 17329746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Large MM, Ryan CJ, Singh SP, Paton MB, Nielssen OB. The predictive value of risk categorization in schizophrenia. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2011;19:25–33. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2011.549770. PMID: 21250894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lauber C, Nordt C, Falcato L, Rossler W. Factors influencing social distance towards people with mental illness. Community Ment Health J. 2004;40:265–74. doi: 10.1023/b:comh.0000026999.87728.2d. PMID: 15259631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee S, Chiu MY, Tsang A, Chui H, Kleinman A. Stigmatizing experience and structural discrimination associated with the treatment of schizophrenia in Hong Kong. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:1685–96. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.016. PMID: 16174547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee S. Socio-cultural and global health perspectives for the development of future psychiatric diagnostic systems. Psychopathology. 2002;35:152–7. doi: 10.1159/000065136. PMID: 12145501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Link BG. Mental patient status, work, and income: An examination of the effects of a psychiatric label. Am Sociol Rev. 1982;47:202–15. PMID: 7091929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: An assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. Am Sociol Rev. 1987;52:96–112. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loganathan S, Murthy SR. Experiences of stigma and discrimination endured by people suffering from schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50:39–46. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.39758. PMID: 19771306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin JK, Pescosolido BA, Tuch SA. Of fear and loathing: The role of “disturbing behavior,” labels, and causal attribution in shaping public attitudes toward people with mental illness. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41:208–23. [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCann TV, Boardman G, Clark E, Lu S. Risk profiles for non-adherence to antipsychotic medications. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2008;15:622–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01277.x. PMID: 18803735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murthy SR. Perspectives on the stigma of mental illness. In: Okasha A, Stefanis CN, editors. Stigma of mental illness in the third world. Geneva: World Psychiatric Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norman RM, Windell D, Manchanda R. Examining differences in the stigma of depression and schizophrenia. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2010 Nov 18; doi: 10.1177/0020764010387062. epub ahead of print. PMID: 21088035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norman RM, Sorrentino RM, Windell D, Manchanda R. The role of perceived norms in the stigmatization of mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43:851–9. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0375-4. PMID: 18575793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patel V, Kleinman A. Poverty and common mental disorders in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:609–15. PMID: 14576893. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Penn DL, Guynan K, Daily T. Dispelling the stigma of schizophrenia: What sort of information is best? Schizophr Bull. 1994;20:567–75. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.3.567. PMID: 7973472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinel EC. Stigma consciousness: The psychological legacy of social stereotypes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;76:114–28. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.1.114. PMID: 9972557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pyne JM, Bean D, Sullivan G. Characteristics of patients with schizophrenia who do not believe they are mentally ill. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189:146–53. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200103000-00002. PMID: 11277350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raguram R, Weiss MG, Channabasavanna SM, Devins GM. Stigma, depression, and somatization in South India. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:115–26. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.8.1043. PMID: 8678173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Read A, Law J. The relationship of causal beliefs and contact with users of mental health services to attitudes to the ‘mentally ill. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1999;45:216–29. doi: 10.1177/002076409904500309. PMID: 10576088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reader GD, Pryor JB. Dual psychological processes underlying public stigma and the implications for reducing stigma. Mens Sana Monogr. 2008;6:175–86. doi: 10.4103/0973-1229.36546. PMID: 22013358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rinnerthaler M, Mueller J, Weichbold V, Wenning GK, Poewe W. Social stigmatization in patients with cranial and cervical dystonia. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1636–40. doi: 10.1002/mds.21049. PMID: 16856133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ronzoni P, Dogra N, Omigbodun O, Bella T, Atitola O. Stigmatization of mental illness among Nigerian school children. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2010;56:507–14. doi: 10.1177/0020764009341230. PMID: 19651693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sartorius N, Gaebel W, Cleveland HR, Stuart H, Akiyama T, Arboleda-Flórez J, et al. WPA guidance on how to combat stigmatization of psychiatry and psychiatrists. World Psychiatry. 2010;9(3):131–44. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00296.x. PMID: 20975855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schulze B, Angermeyer MC. Subjective experiences of stigma: A focus group study of schizophrenic patients, their relatives and mental health professionals. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:299–312. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00028-x. PMID: 12473315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Segal S, Baumohl J, Moyles E. Neighbourhood types and community reaction to the mentally ill: a paradox of intensity. J Health Soc Behav. 1980;21:345–59. PMID: 7204928. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shrivastava A, Johnston ME, Thakar M, Shrivastava S, Sarkhel G, Sunita I, et al. Origin and impact of stigma and discrimination in schizophrenia-patients’ perception: Mumbai study. Stigma Research Action. 2011;1:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh AR, Singh SA. Disease of poverty and lifestyle, well-being and human development. Mens Sana Monogr. 2008;6:187–225. doi: 10.4103/0973-1229.40567. PMID: 22013359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, Perlick DA, Raue P, Friedman SJ, et al. Perceived stigma as a predictor of treatment discontinuation in young and older outpatients with depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:479–81. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.479. PMID: 11229992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, Perlick DA, Friedman JS, Meyer BS. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: Perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1615–20. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1615. PMID: 11726752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Staring AB, Van der Gaag M, Van den Berge M, Duivenvoorden HJ, Mulder CL. Stigma moderates the associations of insight with depressed mood, low self-esteem, and low quality of life in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Res. 2009;115:363–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.06.015. PMID: 19616414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stuart H, Arboleda-Flórez J. Community attitudes toward people with schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46:245–52. doi: 10.1177/070674370104600304. PMID: 11320678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Switaj P, Wciórka J, Smolarska-Switaj J, Grygiel P. Extent and predictors of stigma experienced by patients with schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24:513–20. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.06.003. PMID: 19699063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Elbogen EB, Van Dorn RA. Reducing violence risk in persons with schizophrenia: Olanzapine versus risperidone. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1666–73. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1212. PMID: 15641872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tay SE. Compliance therapy: An intervention to improve inpatients’ attitudes toward treatment. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2007;45:29–37. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20070601-09. PMID: 17601158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thara R, Srinivasan TN. How stigmatizing is schizophrenia in India? Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2000;46:135–41. doi: 10.1177/002076400004600206. PMID: 10950361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thornton JA, Wahl OF. Impact of a newspaper article on attitudes toward mental illness. J Commun Psychol. 1996;24:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tirupati NS, Rangaswamy T, Raman P. Duration of untreated psychosis and treatment outcome in schizophrenia patients untreated for many years. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38:339–43. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01361.x. PMID: 15144511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsang HW, Fung KM, Corrigan PW. Psychosocial treatment compliance scale for people with psychotic disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:561–9. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01839.x. PMID: 16756581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Waggoner RW, Waggoner RW., Jr Psychiatry's image, issues, and responsibility. Psychiatr Hosp. 1983;14:34–8. PMID: 10258440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wahl OF. Mental health consumers’ experience of stigma. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:467–78. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033394. PMID: 10478782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wig NN. Stigma against mental illness. Indian J Psychiatry. 1997;39:187–9. PMID: 21584072. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.World Health Report. Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]