Abstract

cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) is a multifunctional protein. Whether PKG plays a role in ischemia-reperfusion-induced kidney injury (IRI) is unknown. In this study, using an in vivo mouse model of renal IRI, we determined the effect of renal IRI on kidney PKG-I levels and also evaluated whether overexpression of PKG-I attenuates renal IRI. Our studies demonstrated that PKG-I levels (mRNA and protein) were significantly decreased in the kidney from mice undergoing renal IRI. Moreover, PKG-I transgenic mice had less renal IRI, showing improved renal function and less tubular damage compared with their wild-type littermates. Transgenic mice in the renal IRI group had decreased tubular cell apoptosis accompanied by decreased caspase 3 levels/activity and increased Bcl-2 and Bag-1 levels. In addition, transgenic mice undergoing renal IRI demonstrated reduced macrophage infiltration into the kidney and reduced production of inflammatory cytokines. In vitro studies showed that peritoneal macrophages isolated from transgenic mice had decreased migration compared with control macrophages. Taken together, these results suggest that PKG-I protects against renal IRI, at least in part through inhibiting inflammatory cell infiltration into the kidney, reducing kidney inflammation, and inhibiting tubular cell apoptosis.

Keywords: apoptosis inflammation, macrophage

ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury is a major cause of acute renal failure with high morbidity and mortality in patients in shock, renal transplantation, and other clinical settings. Currently, there are still no pharmacological agents available to prevent/treat this severe syndrome. Renal IR injury is a very complex process that involves a variety of pathophysiological mechanisms. Renal IR injury is initiated by the cellular depletion of energy substrates such as ATP during the ischemic phase. The proximal tubule is the major target of IR-induced injury (29). Following reperfusion, a complex series of events occur including generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, generation of proinflammatory cytokines, alteration of microvascular activity, inflammation, and eventually tubular cell death (3). Morphological changes of kidney IR injury include effacement and loss of proximal tubule brush border, proximal tubular dilation and distal tubular casts, necrosis, and apoptosis of proximal tubular cells (6, 17, 39). In addition, rapid accumulation of massive neutrophils and monocyte/macrophages, and fewer leucocytes in the interstitium of injured kidney is another feature of renal IR injury (3, 22, 25).

The role of nitric oxide (NO) in renal IR injury has been extensively investigated (8, 26, 28, 34, 41, 46, 50). However, the involvement of the NO downstream signaling pathway, cGMP and cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG), in renal IR injury has not been investigated. PKG is a serine/threonine kinase consisting of a regulatory and a catalytic domain within one polypeptide chain (48). In mammalian cells, two genes encoding PKG have been identified, type I and type II (18). Type I is alternatively spliced at the first exon to encode two isoforms, Iα and Iβ. These enzymes contain identical catalytic domains (2, 38). PKG-I is expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells, cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, mesangial cells, renal tubular cells, macrophages, and other cell types (9). Recent studies demonstrated the protective effect of the cGMP/PKG signaling pathway on IR injury in the heart as well as in cardiomyocytes through several mechanisms such as regulation of mitochondria KATP channels or enhanced phosphorylation of Akt, ERK, and glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3β (5, 11, 13) . However, whether PKG displays a protective effect on kidney IR injury is unknown.

In this study, we determined how renal IR injury affects PKG-I levels in the kidney and further determined whether overexpression of PKG-I in the kidney and other tissues attenuates renal IR injury by using PKG-I transgenic mice generated by our laboratory (33). We assessed the renal function and structural changes in transgenic mice and wild-type littermates undergoing renal IR injury. In addition, inflammatory cell infiltration into kidney in vivo and macrophage migration in vitro were investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals and protocol.

PKG-I transgenic mice were generated by our laboratory previously (33). Eight-week-old male PKG-I transgenic mice and sex- and age-matched wild-type littermates were used in the studies. All these mice were on a B6C3H background and were cared for in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. There were four groups of animals: 1) transgenic mice, sham; 2) transgenic mice, IR; 3) wild-type littermates, sham; and 4) wild-type littermates, IR. Each group contained 10 mice. For studies involving inhibitors (Sigma), MEK1 inhibitor PD98059 (10 mg/kg), GSK-3β inhibitor SB216763 (10 mg/kg), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor wortmannin (0.75 mg/kg) were administered to PKG-I transgenic mice (ip) 30 min before renal IR injury. To perform renal IR injury, mice were anesthetized and subjected to bilateral flank incisions. Then, the right kidney was cut and the left renal pedicle was clamped for 45 min as described previously (35). Surgical wounds were closed, and the mice were returned to cages for 24 h. After 24 h of reperfusion, the mice were euthanized. Blood was collected, and the kidneys were harvested for various analyses. All protocols were approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the University of Kentucky Animal Care Committee.

Kidney microdissection.

Kidney microdissection was performed as described previously by Wakamatsu et al. (44). Briefly, the mice were anesthetized and perfused with cold Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS). Then, the kidney was excised, sliced, and digested in HBSS containing 1 mg/ml type I collagenase and 10 mM RNase inhibitor. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, the slices were washed in HBSS and microdissected under a stereomicroscope. The glomeruli, proximal tubules, and distal tubules plus collecting ducts were isolated and collected to determine the alteration of PKG mRNA and protein levels by real-time PCR or immmunoblotting, respectively.

Renal function, histology, immunohistochemical staining, and terminal transferase dUTP nick-end labeling assay.

Plasma creatinine concentrations were determined using a kit from Pierce (Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

For histology, kidneys were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Histological changes including loss of brush border, tubular dilation, cast formation, and cell lysis were evaluated. Kidney damages were examined in a blind manner and scored as follows: 1, <25% damage; 2, 25–50% damage; 3. 50–75% damage; and 4. >75% damage.

For kidney section staining, formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded renal tissues were cut into 4- to 5-μm sections. Sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in graded mixtures of ethanol/water. The slides were stained with anti-F4/80 antibody (Serotech) or anti-active caspase 3 antibody (Cell Signaling) using the VECTASTAIN Elite ABC system (Vector Labs) following the instruction manual. The color was developed with 2,3-diaminobenzidine.

A terminal transferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay was used to analyze apoptosis in kidney sections using In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit Fluorescein (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) and performed according to the protocol manual. After staining, mounting media containing 4,6-diamidino-phenylindole was applied to slides. The slides were examined by fluorescence microscopy.

Caspase 3 activity assay.

Kidneys were homogenized and briefly centrifuged. The supernatants were collected, and caspase 3 activity in the supernatants (∼200 μg protein/sample) was measured using a Caspase 3 Colorimetric Assay Kit (catalog no. K106, BioVision Research Products, Mountain View, CA) following the manufacturer's protocol.

Real-time PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from kidney tissue using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and treated with DNaseI (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). The treated RNA was cleaned up using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Two micrograms of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis with a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR analyses were performed using a SYBR Green PCR Master Mix kit with a MyiQ Real-time PCR Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad). PCR conditions were 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. All reactions were performed in triplicate in a final volume of 25 μl. Dissociation curves were run to detect nonspecific amplification, and we confirmed that single products were amplified in each reaction. The quantities of each test gene and internal control 18S RNA were then determined from the standard curve using MyiQ system software, and mRNA expression levels of test genes were normalized to 18S RNA levels. The primer sequences are shown in Table 1.

Table 1:

Sequences of primers used in the study

| Gene | Sense (5′-3′) | Antisense (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| 18S RNA | AG AGTCGG CAT CGT TTA TGG TC | CGA AAG CAT TTG CCA AGA AT |

| IL-6 | CTG CAA GAG ACT TCC ATC CAG TT | GAA GTA GGG AAG GCC GTG G |

| TNF-α | AGC CGA TGG GTT GTA CCT | TGA GTT GGT CCC CCT TCT |

| MCP-1 | CAG CCA GAT GCA GTT AAC GC | GCC TAC TCA TTG GGA TCA TCT TG |

| IL-1β | TGG AGA GTG TGG ATC CCA AGC AAT | GT CCT GAC CAC TGT TGT TTC CCA |

| CCR2 | AGA GAG CTG CAG CAA AAA GG | GGA AAG AGG CAG TTG CAA AG |

| PKG-Iα | AAA CTC CAC AAA TGC CAG TCG GTG | TTT AGT GAA CTT CCG GAA CGC CTG |

| PKG-Iβ | TAC AGT ATG CGC TCC AGG AGA AGA | TCA CCG AGC GAT ACT TGT CCA GTT |

| PAI-1 | GCG TGT CAG CTC GTC TAC AG | GTA CTG CGG ATG CCA TCT TT |

MCP, monocyte chemoattractant protein; PKG, cGMP-dependent protein kinase; PAI, plasminogen activator inhibitor.

In addition, 1 μg total RNA was used for the cDNA synthesis using a First Strand cDNA kit (Qiagen). The mouse apoptosis PCR array was performed using the RT2 Profiler Real-Time PCR Array System (Qiagen). After running in a real-time PCR machine, the raw data were collected and loaded onto the Qiagen website and analyzed online.

Immunoblot analysis and ELISA.

Mice from experimental groups were euthanized, and their kidneys were collected and homogenized. Kidney homogenates were subjected to SDS-PAGE gel under reducing condition and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking, the membrane was incubated with anti-PKG-I antibody (Stressgene), anti-Bcl-2, anti-Bag1, anti-p-ERK, or anti-total ERK (Cell Signaling) at 4°C overnight. After washing, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson Labs). The reaction was visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Pierce). Immunoblots were analyzed by scanning densitometry and quantified by Quantity One gel Analysis software (Bio-Rad). In addition, protein levels of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-1 in the kidney homogenates were determined by ELISA using kits purchased from eBiosciences (San Diego, CA) for IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 and from Innovative Research (Novi, MI) for PAI-1.

Flow cytometry analysis.

Kidney tissues were cut into small pieces and incubated with digestion buffer containing 10 μg/ml collagenase type 1A (Sigma) in D-PBS buffer for 15 min at 37°C with occasional shaking. The digested kidney tissue was then passed through different sizes of cell strainer (100 and 70 μm) and briefly centrifuged at 2,000 rpm at room temperature. The cell pellet was collected. For detection of neutrophils: the cell pellet was suspended in sorting buffer containing 1% FBS in D-PBS buffer. About 106 kidney cells were incubated with rat anti-mouse neutrophil Ab (catalog no. CL8993AP, Cedarlane, Burlington, ON) for 30 min at room temperature. After washing, cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG for 30 min at room temperature. The labeled cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. For detection of macrophages from the pool of kidney mononuclear cells, kidney mononuclear cells were isolated from kidneys using the method as described previously (1). Briefly, the cell pellet was suspended in 36% Percoll (Sigma), slowly loaded onto 72% Percoll, and centrifuged at 1,000 g for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were taken from the Percoll interface, washed for two times with sorting buffer containing 1% FBS in D-PBS buffer, and incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-CD11b antibody (1:50, BD Pharmingen) for 30 min at room temperature. The labeled cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using the Flow Cytometry Service Facility at the University of Kentucky.

Macrophage migration assays.

Macrophage migration assays were performed using a 24-well Transwell plate (8-um pore size; Costar, Corning, NY). Peritoneal macrophages were isolated from male PKG transgenic mice and wild-type littermate controls using the methods as described previously (31). Peritoneal macrophages at a density of 1 × 10 6 cells were loaded into the upper chambers, and the lower chamber was filled with either DMEM with 0.2% BSA or DMEM with 0.2% BSA and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1; 50 ng/ml) and incubated at 37°C for 5 h. Media was removed from the upper chamber. Cells in the bottom chamber were then fixed in methanol and stained with Giemsa solution (Dade Behring, Marburg. Germany). Cell counts were performed by two different observers who were blinded to the study design. Migration was expressed as the number of cells per field.

Statistical analysis.

All data are expressed as means ± SE. ANOVA was used to analyze variations within the group. Student's t-tests were used to compare variations between groups. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

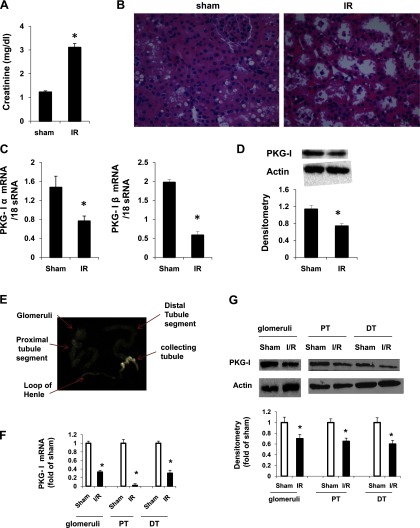

Renal IR injury downregulates kidney PKG-I levels.

To determine the effect of IR injury on kidney PKG-I levels, control mice underwent renal ischemia (45 min)-reperfusion (24 h) injury as described in materials and methods. This has been considered to be a moderate acute kidney failure animal model (15, 35). We demonstrated that mice from the IR group exhibited a significant increase in plasma creatinine levels compared with the sham group (Fig. 1A). In accordance with the renal functional analysis, renal histology revealed severe tubular damage including loss of brush border and vacuolation or necrosis in mice from the IR group (Fig. 1B). Together, these results demonstrated that mice from the IR group exhibited severe kidney damage. In this renal IR injury model, we found that expression of PKG-I (mRNA and protein levels) in the kidney was significantly decreased in the IR group compared with the sham group (Fig. 1, C and D). To further determine whether the IR-induced decrease in the levels of PKG-I is specific to proximal or distal tubules or both, we performed microdissection of proximal tubules from wild-type mice under sham surgery or IR injury. The glomeruli, proximal tubules, and distal tubules plus collecting ducts were isolated and collected to determine the alteration of PKG mRNA and protein levels by real-time PCR or immmunoblotting, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1, E–G, IR injury-induced PKG-I reduction (mRNA and protein levels) occurred in glomeruli, proximal tubules, and distal tubules.

Fig. 1.

cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG)-I levels (mRNA and protein) in the kidney were downregulated in a ischemia-reperfusion (IR)-induced kidney injury mouse model. A: plasma creatinine levels in wild-type control mice from sham or ischemia (45 min)-reperfusion (24 h)-induced kidney injury group. Values are means ± SE (n = 8). B: representative light micrographs of hematoxylin-eosin (HE)-stained kidney sections from sham and IR groups. Scale bar = 50 μm. Original magnification ×40. PKG-I mRNA levels (C) and protein levels (D) in the kidney were determined by real-time PCR and Western blotting, respectively, as described in materials and methods. E: microdissection was done to isolate glomeruli, proximal tubules (PT), and distal tubules (DT) from the kidneys. Real-time PCR (F) or immunoblotting (G) was performed to determine PKG-I levels in these segments. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. sham group.

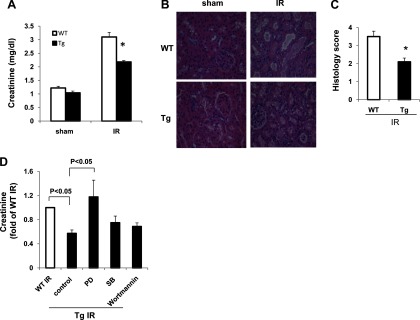

PKG-I transgenic mice have reduced IR injury.

The above results demonstrated that endogenous PKG-I levels in the kidney were downregulated in renal IR injury. In the following studies, we used PKG-I transgenic mice generated by our laboratory previously (33) to determine whether overexpression of PKG-I prevents/attenuates renal IR injury. In PKG transgenic mice, constitutively active PKG-I was overexpressed in the kidney as well as in other tissues (33). Transgenic mice and wild-type control littermates underwent renal IR injury (45-min ischemia/24-h reperfusion). Renal function and histology were examined. As shown in Fig. 2A, plasma creatinine levels were significantly reduced in transgenic mice from the IR group compared with wild-type controls. Consistently, renal histology revealed significantly less tubular damage in transgenic mice after ischemic injury (Fig. 2, B and C). In this study, a PKG-I knockout mouse was not used due to its very limited lifespan (∼4 wk) (20).

Fig. 2.

PKG-I transgenic (Tg) mice had decreased plasma creatinine levels and renal tubular damage in a renal IR injury model. A: plasma creatinine levels in wild-type (WT) mice or PKG-I Tg mice from sham or ischemia (45 min)-reperfusion (24 h)-induced kidney injury group. Values are means ± SE (n = 5). B: representative light micrographs of HE-stained kidney sections from 4 groups of mice. Scale bar = 50 μm. Original magnification ×40. C: histology scores for IR group from WT or Tg mice were determined as described in materials and methods. Values are means ± SE (n = 5). *P < 0.05 vs. WT IR group. D: PKG-I Tg mice were treated with or without PD98059 (10 mg/kg), SB216763 (10 mg/kg), or wortmannin (0.75 mg/kg) for 30 min before IR injury was performed. After ischemia (45 min)-reperfusion (24 h) injury, plasma creatinine levels were measured.

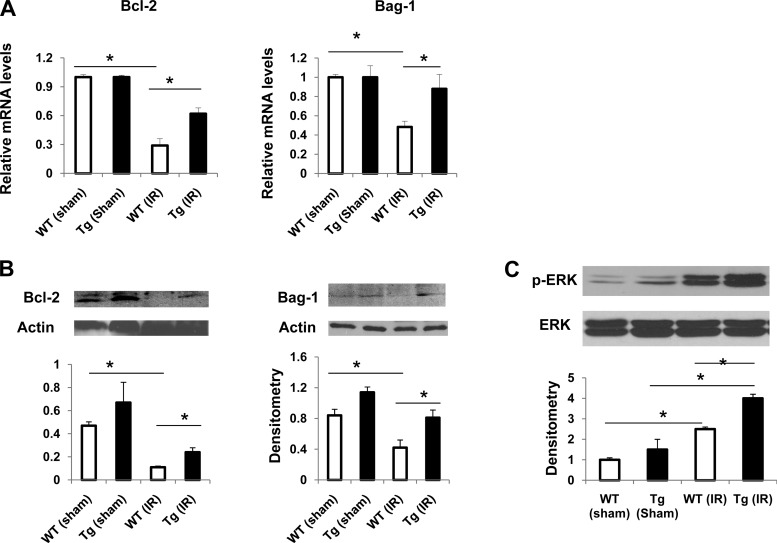

Several PKG-associated downstream targets have been demonstrated in the kidney or heart, such as ERK, GSK-3β, and PI3K/Akt (10–13). To determine which PKG-associated downstream targets might play a role in the protection in our PKG-I transgenic mice under IR injury, MEK1 inhibitor PD98059 (10 mg/kg), GSK-3β inhibitor SB216763 (10 mg/kg), and PI3K inhibitor wortmannin (0.75 mg/kg) were administered to PKG-I transgenic mice (ip) 30 min before IR injury. The results demonstrated that administration of the PD compound abolished the protective effect of overexpression of PKG-I on kidney IR injury. However, the GSK-3β inhibitor or PI3K inhibitor had no effect (Fig. 2D). These data suggest that protection of PKG-I transgenic mice under IR injury is mediated by the ERK pathway. Consistent with this result, phospho-ERK levels were increased in the IR-injured kidneys from PKG-I transgenic mice compared with wild-type mice (see Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Expression of Bcl-2, Bag-1, and p-ERK in the kidneys from sham or IR groups of mice. Expression of antiapoptotic genes (Bcl-2 and Bag-1) in kidney from 4 groups of mice was analyzed by real-time PCR (A) and immunoblotting (B). Values are means ± SE (n = 3). C: protein levels of p-ERK and total ERK in kidneys from 4 groups of mice were determined by immunoblotting. Immunoblots were analyzed by scanning densitometry and quantified by Quantity One gel Analysis software. Representative immunoblots are shown. Values are means ± SE (n = 4). *P < 0.05.

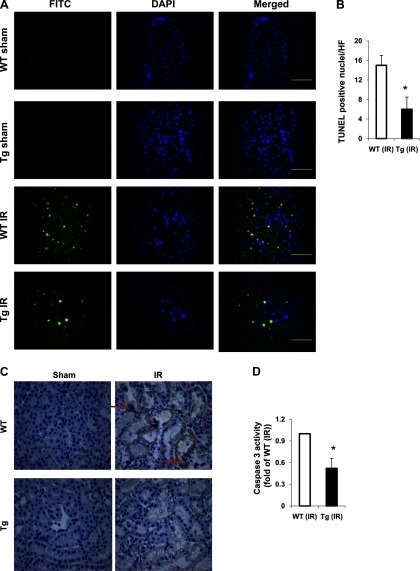

In addition to acute necrotic damage, tubular apoptosis contributes to the development of ischemic acute kidney injury (17). To determine whether there is an alteration in tubular apoptosis in transgenic mice in the above IR injury model, we examined renal tissues by TUNEL assay. In kidneys from both sham groups, apoptotic cells were rare. However, in kidneys from the IR group, apoptotic cells were significantly increased in wild-type mice compared with transgenic mice (Fig. 3, A and B). Consistently, active caspase 3 staining (Fig. 3C) or caspase 3 activity was significantly reduced in transgenic mice from the IR group compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 3D). Moreover, we determined the expression of antiapoptotic, proapoptotic, or survival proteins in the kidney. We found that expression (mRNA and protein levels) of antiapoptotic genes Bcl-2 and Bag-1 was significantly decreased in wilt-type (IR) kidneys, which was inhibited in transgenic mice (Fig. 4, A and B). The expression of Bax in the kidney (in cytosol or mitochondria) was similar between wild-type and transgenic mice (data not shown). In addition, IR injury increased p-ERK levels in the kidneys from both wild-type and transgenic mice. However, p-ERK levels were increased to a greater extent in transgenic mice (IR) than in wild-type mice (IR) (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these results demonstrated that PKG-I transgenic mice have reduced tubular apoptosis in renal IR injury partially through upregulation of antiapoptotic or survival signaling molecules in the kidney.

Fig. 3.

PKG-I transgenic mice had reduced tubular cell apoptosis and decreased caspase 3 levels and activity in the kidney in a renal IR injury model. A: a terminal transferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay was used to analyze apoptosis in kidney sections from 4 groups of mice using an In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit Fluorescein from Roche as described in materials and methods. Representative fluorescence micrographs are shown. Apoptotic cells are labeled as green. Cell nuclei were stained with 4,6-diamidino-phenylindole (DAPI) and shown as blue. Scale bars = 100 μm. Original magnification ×40. B: TUNEL-positive nuclei were calculated. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). C: representative light micrographs of active caspase 3 immunostaining in kidney sections from 4 groups of mice. The positive staining is shown as brown (indicated by arrows). Original magnification ×40. D: caspase 3 activity in the kidneys from 4 groups of mice were analyzed. Values are means ± SE (n = 5). *P < 0.05 vs. WT IR group.

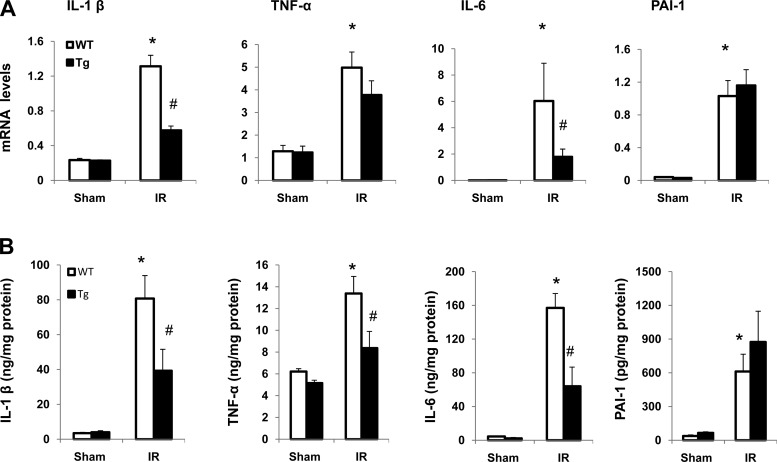

PKG-I transgenic mice have reduced expression of renal cytokines in a renal IR injury model.

Accumulating evidence suggests that an inflammatory response plays a role in ischemic acute kidney injury (17). To determine the effect of overexpression of PKG-I on local inflammation in renal IR injury, the mRNA (Fig. 5A) and protein levels (Fig. 5B) of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and PAI-1 were examined. The results demonstrated that IR significantly increased expression of all of these four cytokines in the kidney from both wild-type and transgenic mice compared with their sham groups. However, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α protein levels were significantly reduced in the transgenic mice IR group compared with the wild-type IR group, suggesting that PKG-I represses IR injury-induced local kidney inflammation.

Fig. 5.

Expression of inflammatory cytokines in the kidney from sham or IR groups of mice A: expression of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-1 in the kidney was determined by real-time PCR as described in materials and methods. B: protein levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and PAI-1 in the kidney were determined by ELISA. Values are means ± SE (n = 6). *P < 0.05 vs. WT sham group. #P < 0.05 vs. WT IR group.

PKG-I transgenic mice have reduced macrophage infiltration into the kidney in a renal IR injury model.

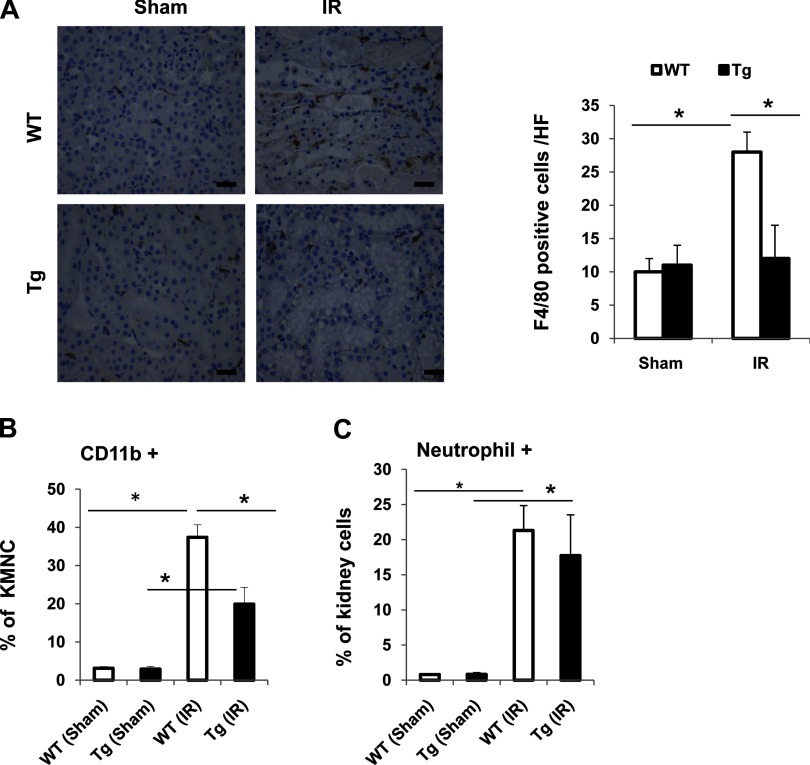

To determine the mechanism of a reduced inflammatory response in kidneys from transgenic mice after IR, we investigated the accumulation of neutrophils and macrophages in the injured kidneys. First, macrophage infiltration into the kidney was determined by immunohistochemical staining renal tissues with the macrophage marker anti-F4/80 antibody or by flow cytometry analysis using an anti-CD11b antibody, another murine macrophage marker. Second, neutrophil infiltration was determined by flow cytometry analysis. As shown in Fig. 6A, there was no significant difference of F4/80-positive cells in the sham group between wild-type mice and transgenic mice. However, in the IR group, F4/80-positive cells were significantly increased in wild-type mice compared with transgenic mice. Consistently, CD11b-positive macrophages were significantly decreased in transgenic IR kidneys compared with wild-type IR kidneys as demonstrated by flow cytometry (Fig. 6B). Neutrophil infiltration in the kidney was similarly increased in IR mice from both wild-type and transgenic groups (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, we examined the expression of MCP-1 and its cognate receptor CCR2 in the kidneys from sham or IR groups. IR similarly increased renal MCP-1 expression in both wild-type and transgenic mice (data not shown). Kidney CCR2 levels were not altered by IR and were similar in the sham and IR groups for both wild-type and transgenic mice (data not shown). Together, these data suggest that PKG transgenic mice have reduced IR injury-induced microphage infiltration into the kidney possibly through a MCP-1-independent mechanism.

Fig. 6.

Macrophage infiltration into kidney was decreased in Tg mice undergoing IR-induced kidney injury. A: kidney sections from 4 groups of mice were stained with anti-F4/80 antibody. The positive staining is shown as brown. Representative light micrographs are shown. Scale bars = 50 μm. Original magnification ×40. F4/80-positive cells were also calculated. Values are means ± SE (n = 5). *P < 0.05. Isolated kidney mononuclear cells (KMNC) from 4 groups of mice were stained with anti-CD11b antibody (B), or kidney cells isolated from 4 groups of mice were stained with anti-neutrophil antibody (C) and analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentage of CD11b+ cells within KMNCs or neutrophil+ cells within the whole kidney cell populations was calculated. Values are means ± SE (n = 3). *P < 0.05.

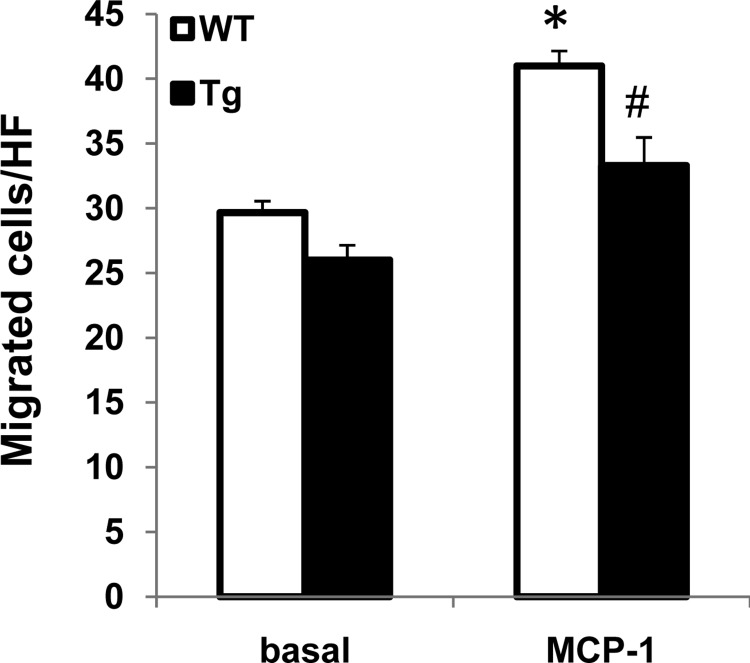

Peritoneal macrophages isolated from PKG transgenic mice show decreased migration.

To further determine the effect PKG-I on macrophage function, peritoneal macrophages were isolated from wild-type and PKG-I transgenic mice and underwent migration to the known macrophage chemoattractant (MCP-1; 50 ng/ml) in vitro. The results demonstrated that peritoneal macrophages isolated from transgenic mice had decreased ability to migrate toward MCP-1 (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Macrophages from Tg mice had decreased migration. Basal or monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1; 50 ng/ml)-stimulated peritoneal macrophage migration was determined as described in materials and methods. Values are means ± SE (n = 5). *P < 0.05 vs. WT (basal). #P < 0.05 vs. WT (MCP-1).

DISCUSSION

In this study, the role of PKG-I in renal IR injury was investigated. Using an acute kidney injury mouse model, we first demonstrated that IR injury downregulated PKG-I levels in the kidney. Moreover, overexpression of PKG-I attenuated renal IR injury, which was accompanied by reduced tubular cell apoptosis partially due to increased expression of antiapoptotic genes (Bcl-2 and Bag-1) or increased levels of phosphorylated ERK. Inhibitor studies further support the involvement of an ERK pathway in PKG-I-mediated renal IR protection. Additionally, decreased accumulation of macrophages and reduced expression of proinflammatory cytokines in the injured kidneys were demonstrated in PKG-I transgenic mice, which is consistent with the observed decreased mobility of macrophages from transgenic mice. Together, these results suggest that PKG-I has a protective effect on renal IR injury partially through inhibiting tubular cell apoptosis and suppressing kidney inflammation.

PKG is a downstream signaling mediator of NO and cGMP. It is a serine/threonine kinase, consisting of a regulatory and a catalytic domain. Binding of cGMP by the regulatory domain leads to activation of the catalytic domain and increases PKG activity (48). PKG levels/activity have been shown to be modulated in many disease conditions. For example, PKG expression is downregulated in diabetes or cancer (7, 16, 21). Our previous studies demonstrated that the NO and cGMP levels were decreased in kidney mesangial cells under high-glucose conditions, resulting in decreased PKG kinase activity (45, 48). In vascular smooth muscle cells, glucose decreases PKG mRNA and protein levels through PKC-dependent activation of NAD(P)H oxidase-derived superoxide production (30). In the current studies, we found that mRNA and protein levels of PKG-I in the kidney were also downregulated in IR-induced kidney injury. The increased production of reactive oxygen species or inflammatory cytokines under IR conditions may contribute to the decreased PKG levels in IR kidneys (4, 32). The cellular and molecular mechanisms of renal IR injury induced downregulation of PKG-I expression in the kidney need to be further investigated.

In this study, we demonstrated that overexpression of PKG-I attenuates IR-induced kidney injury. One mechanism is possibly due to decreased apoptosis and necrosis in tubular cells in PKG transgenic mice. It is known that apoptosis is one of the important mechanisms of cell death from renal IR injury in renal tubular cells in vitro as well as in the kidneys. We observed a significant increase in antiapoptotic genes including Bcl-2 and Bag-1 levels (mRNA and protein) and a decrease in caspase 3 levels/activity in the kidneys from transgenic mice. Bcl-2 is a membrane protein that blocks a step in a pathway leading to cell apoptosis (43). BAG1 (or Bcl-2-associated athanogene 1) was identified by Takayama et al. in 1995 and has been described as a multifunctional protein able to delay cell death (42). BAG1 interacts with Bcl-2 and enhances the antiapoptotic effects of Bcl-2 (42). Therefore, PKG-I-mediated upregulation of both Bcl-2 and BAG1 in the kidney may greatly contribute to the decreased renal IR injury-induced tubular cell apoptosis in PKG-I transgenic mice. Consistently, the number of TUNEL-positive cells was significantly decreased in the kidney tubular cells from transgenic mice, suggesting the antiapoptotic effect of PKG on renal IR injury. This antiapoptotic effect of PKG has also been revealed in neural cells and in vascular smooth muscle cells (23, 49). In addition to regulating the expression of antiapoptotic genes, other mechanisms may also contribute to the antiapoptotic effect of PKG on renal IR, such as PKG-mediated direct phosphorylation of NF-κB proteins (19, 24) or PKG-mediated opening of mitochondria KATP channels and decreases in calcium influx (36). Recently, the survival signaling such as ERK or Akt has been shown to be phosphorylated by PKG in cardiomyocytes and plays a role in PKG-induced cytoprotection (13). Consistent with these reports, we found that the levels of phosphorylated ERK in the kidney were increased to a greater extent in the IR group of transgenic mice than in wild-type mice. In vivo inhibitor studies further support the involvement of the ERK pathway in PKG-I-mediated renal IR protection. Together, our data suggest that PKG upregulates antiapoptotic genes and increases the phosphorylation of ERK in the kidney. Both of these effects contribute to the antiapoptotic effect of PKG in kidney tubular cells under kidney IR injury.

In addition to acute tubular necrosis/apoptosis, accumulating evidence supports the role of an innate immune response and inflammation in the pathogenesis of renal IR injury. Renal IR injury is associated with the rapid accumulation of a massive number of neutrophils and monocyte/macrophages in the interstitium of injured kidney (3, 22, 25, 27). Animal studies have shown that macrophage depletion in the mouse or rat attenuates renal IR injury, while adoptive macrophage transfer into these animals reconstitutes renal IR injury (14, 22), supporting the important role of macrophages in renal IR injury. Whether PKG has an effect on an innate immune response and kidney inflammation in renal IR injury is not known. In this study, we demonstrated that PKG-I transgenic mice had decreased macrophage accumulation in the injured kidney. This is partially due to decreased macrophage recruitment, since the decreased in vitro macrophage migration was observed in PKG transgenic mice. Furthermore, similar levels of a known macrophage chemoattractant, MCP-1, or receptor CCR2 were identified between transgenic mice and wild-type mice under IR injury conditions. This suggests that PKG inhibits macrophage migration by a MCP-1-independent mechanism, possibly through a Rho GTPase-mediated mechanism (37, 40). Consistent with the decreased macrophage accumulation in injured kidneys from transgenic mice, the expression of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-6 in the kidney was significantly decreased. Although studies have shown that PKG regulates neutrophil functions such as chemotaxis and granule secretion (47), in this study transgenic and wild-type mice had similar levels of infiltrated neutrophils in the injured kidneys. Taken together, our results suggest that PKG regulates macrophage chemotaxis, leading to decreased macrophage accumulation in the kidney and suppressed kidney inflammation under IR conditions, resulting in attenuated kidney IR injury.

There is a limitation of the current study. By using PKG-I global transgenic mice, our studies suggest that PKG may have a direct effect on both tubular cells and macrophages, contributing to its protective effect on renal IR injury. To demonstrate the effect of tubular cell PKG on renal IR injury, tissue-specific transgenic or knockout mice may be needed. In addition, macrophage depletion and an adoptive transfer approach may help to define the specific effect of macrophage PKG on renal IR injury. Our future studies will define the above-mentioned cell type-specific effect of PKG on renal IR injury.

In summary, PKG transgenic mice and wild-type controls were subjected to IR injury in a single-kidney model which mimics the kidney transplant setting. We found that PKG levels in the kidney were downregulated in IR-induced kidney injury in wild-type mice. PKG-I transgenic mice developed less IR-induced kidney injury, which was associated with significantly decreased macrophage infiltration into the kidney, decreased kidney inflammation, and tubular cell apoptosis. The results of this study are relevant to the field of kidney transplantation and may lead to the development of novel therapies to prevent the development of renal IR injury.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK-081555 (to S. Wang), award P20RR021954 from the National Center for Research Resources (to S. Wang), a Carl W. Gottschalk Research Scholar Grant from the American Society of Nephrology (to S. Wang), the Interdisciplinary Cardiovascular Training Program (T32 HL072743-A to K. Clemons), and the 973 program-2011CB503902 (to J.-M. Cao).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: Y.L., X.T., H.M., and K.C. performed experiments; Y.L. and S.W. analyzed data; Y.L., X.T., H.M., K.C., J.-M.C., and S.W. approved final version of manuscript; X.T. and S.W. prepared figures; J.-M.C. and S.W. edited and revised manuscript; S.W. provided conception and design of research; S.W. interpreted results of experiments; S.W. drafted manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ascon DB, Lopez-Briones S, Liu M, Ascon M, Savransky V, Colvin RB, Soloski MJ, Rabb H. Phenotypic and functional characterization of kidney-infiltrating lymphocytes in renal ischemia reperfusion injury. J Immunol 177: 3380–3387, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boerth NJ, Dey NB, Cornwell TL, Lincoln TM. Cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase regulates vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype. J Vasc Res 34: 245–259., 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bonventre JV, Weinberg JM. Recent advances in the pathophysiology of ischemic acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 2199–2210, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Browner NC, Sellak H, Lincoln TM. Downregulation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase expression by inflammatory cytokines in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287: C88–C96, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burley DS, Ferdinandy P, Baxter GF. Cyclic GMP and protein kinase-G in myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion: opportunities and obstacles for survival signaling. Br J Pharmacol 152: 855–869, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Castaneda MP, Swiatecka-Urban A, Mitsnefes MM, Feuerstein D, Kaskel FJ, Tellis V, Devarajan P. Activation of mitochondrial apoptotic pathways in human renal allografts after ischemia reperfusion injury. Transplantation 76: 50–54, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang S, Hypolite JA, Velez M, Changolkar A, Wein AJ, Chacko S, DiSanto ME. Downregulation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase-1 activity in the corpus cavernosum smooth muscle of diabetic rabbits. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R950–R960, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chatterjee PK. Novel pharmacological approaches to the treatment of renal ischemia-reperfusion injury: a comprehensive review. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 376: 1–43, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coffey MJ, Phare SM, Luo M, Peters-Golden M. Guanylyl cyclase and protein kinase G mediate nitric oxide suppression of 5-lipoxygenase metabolism in rat alveolar macrophages. Biochim Biophys Acta 1781: 299–305, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen MV, Yang XM, Liu Y, Solenkova NV, Downey JM. Cardioprotective PKG-independent NO signaling at reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H2028–H2036, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Das A, Salloum FN, Xi L, Rao YJ, Kukreja RC. ERK phosphorylation mediates sildenafil-induced myocardial protection against ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H1236–H1243, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Das A, Smolenski A, Lohmann SM, Kukreja RC. Cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase Ialpha attenuates necrosis and apoptosis following ischemia/reoxygenation in adult cardiomyocyte. J Biol Chem 281: 38644–38652, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Das A, Xi L, Kukreja RC. Protein kinase G-dependent cardioprotective mechanism of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition involves phosphorylation of ERK and GSK3beta. J Biol Chem 283: 29572–29585, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Day YJ, Huang L, Ye H, Linden J, Okusa MD. Renal ischemia-reperfusion injury and adenosine 2A receptor-mediated tissue protection: role of macrophages. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F722–F731, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Greef KE, Ysebaert DK, Dauwe S, Persy V, Vercauteren SR, Mey D, De Broe ME. Anti-B7–1 blocks mononuclear cell adherence in vasa recta after ischemia. Kidney Int 60: 1415–1427, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deguchi A, Thompson WJ, Weinstein IB. Activation of protein kinase G is sufficient to induce apoptosis and inhibit cell migration in colon cancer cells. Cancer Res 64: 3966–3973, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Devarajan P. Update on mechanisms of ischemic acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1503–1520, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Francis SH, Corbin JD. Structure and function of cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinases. Annu Rev Physiol 56: 237–272., 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. He B, Weber GF. Phosphorylation of NF-kappaB proteins by cyclic GMP-dependent kinase. A noncanonical pathway to NF-kappaB activation. Eur J Biochem 270: 2174–2185., 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hofmann F, Feil R, Kleppisch T, Schlossmann J. Function of cGMP-dependent protein kinases as revealed by gene deletion. Physiol Rev 86: 1–23, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jacob A, Smolenski A, Lohmann SM, Begum N. MKP-1 expression and stabilization and cGK Ialpha prevent diabetes-associated abnormalities in VSMC migration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287: C1077–C1086, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jo SK, Sung SA, Cho WY, Go KJ, Kim HK. Macrophages contribute to the initiation of ischaemic acute renal failure in rats. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 1231–1239, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Johlfs MG, Fiscus RR. Protein kinase G type-Ialpha phosphorylates the apoptosis-regulating protein Bad at serine 155 and protects against apoptosis in N1E-115 cells. Neurochem Int 56: 546–553, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kaltschmidt B, Kaltschmidt C, Hofmann TG, Hehner SP, Droge W, Schmitz ML. The pro- or anti-apoptotic function of NF-kappaB is determined by the nature of the apoptotic stimulus. Eur J Biochem 267: 3828–3835, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kinsey GR, Li L, Okusa MD. Inflammation in acute kidney injury. Nephron Exp Nephrol 109: e102–e107, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kwon O, Hong SM, Ramesh G. Diminished NO generation by injured endothelium and loss of macula densa nNOS may contribute to sustained acute kidney injury after ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F25–F33, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee S, Huen S, Nishio H, Nishio S, Lee HK, Choi BS, Ruhrberg C, Cantley LG. Distinct macrophage phenotypes contribute to kidney injury and repair. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 317–326, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lieberthal W. Biology of ischemic and toxic renal tubular cell injury: role of nitric oxide and the inflammatory response. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 7: 289–295, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lieberthal W, Nigam SK. Acute renal failure. I. Relative importance of proximal vs. distal tubular injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 275: F623–F631, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu S, Ma X, Gong M, Shi L, Lincoln T, Wang S. Glucose down-regulation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase I expression in vascular smooth muscle cells involves NAD(P)H oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med 42: 852–863, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moran JM, Buller RM, McHowat J, Turk J, Wohltmann M, Gross RW, Corbett JA. Genetic and pharmacologic evidence that calcium-independent phospholipase A2beta regulates virus-induced inducible nitric-oxide synthase expression by macrophages. J Biol Chem 280: 28162–28168, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mortensen J, Shames B, Johnson CP, Nilakantan V. MnTMPyP, a superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetic, decreases inflammatory indices in ischemic acute kidney injury. Inflamm Res 60: 299–307, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nikolic DM, Li Y, Liu S, Wang S. Overexpression of constitutively active PKG-I protects female, but not male mice from diet-induced obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 19: 784–791, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Noiri E, Nakao A, Uchida K, Tsukahara H, Ohno M, Fujita T, Brodsky S, Goligorsky MS. Oxidative and nitrosative stress in acute renal ischemia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F948–F957, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Persy VP, Verhulst A, Ysebaert DK, De Greef KE, De Broe ME. Reduced postischemic macrophage infiltration and interstitial fibrosis in osteopontin knockout mice. Kidney Int 63: 543–553, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Qin Q, Yang XM, Cui L, Critz SD, Cohen MV, Browner NC, Lincoln TM, Downey JM. Exogenous NO triggers preconditioning via a cGMP- and mitoKATP-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H712–H718, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ridley AJ. Regulation of macrophage adhesion and migration by Rho GTP-binding proteins. J Microsc 231: 518–523, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ruth P. Cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinases: understanding in vivo functions by gene targeting. Pharmacol Ther 82: 355–372., 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Safirstein RL. Acute renal failure: from renal physiology to the renal transcriptome. Kidney Int Suppl 91: S62–S66, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sawada N, Itoh H, Miyashita K, Tsujimoto H, Sone M, Yamahara K, Arany ZP, Hofmann F, Nakao K. Cyclic GMP kinase and RhoA Ser188 phosphorylation integrate pro- and antifibrotic signals in blood vessels. Mol Cell Biol 29: 6018–6032, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schneider R, Raff U, Vornberger N, Schmidt M, Freund R, Reber M, Schramm L, Gambaryan S, Wanner C, Schmidt HH, Galle J. l-Arginine counteracts nitric oxide deficiency and improves the recovery phase of ischemic acute renal failure in rats. Kidney Int 64: 216–225, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Takayama S, Sato T, Krajewski S, Kochel K, Irie S, Millan JA, Reed JC. Cloning and functional analysis of BAG-1: a novel Bcl-2-binding protein with anti-cell death activity. Cell 80: 279–284, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tsujimoto Y. Cell death regulation by the Bcl-2 protein family in the mitochondria. J Cell Physiol 195: 158–167, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wakamatsu S, Nonoguchi H, Ikebe M, Machida K, Izumi Y, Memetimin H, Nakayama Y, Nakanishi T, Kohda Y, Tomita K. Vasopressin and hyperosmolality regulate NKCC1 expression in rat OMCD. Hypertens Res 32: 481–487, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang S, Shiva S, Poczatek MH, Darley-Usmar V, Murphy-Ullrich JE. Nitric oxide and cGMP-dependent protein kinase regulation of glucose-mediated thrombospondin 1-dependent transforming growth factor-beta activation in mesangial cells. J Biol Chem 277: 9880–9888., 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Weight SC, Furness PN, Nicholson ML. Nitric oxide generation is increased in experimental renal warm ischaemia-reperfusion injury. Br J Surg 85: 1663–1668, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Werner CG, Godfrey V, Arnold RR, Featherstone GL, Bender D, Schlossmann J, Schiemann M, Hofmann F, Pryzwansky KB. Neutrophil dysfunction in guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate-dependent protein kinase I-deficient mice. J Immunol 175: 1919–1929, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wernet W, Flockerzi V, Hofmann F. The cDNA of the two isoforms of bovine cGMP-dependent protein kinase. FEBS Lett 251: 191–196., 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wong JC, Fiscus RR. Protein kinase G activity prevents pathological-level nitric oxide-induced apoptosis and promotes DNA synthesis/cell proliferation in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc Pathol 19: e221–e231, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yu L, Gengaro PE, Niederberger M, Burke TJ, Schrier RW. Nitric oxide: a mediator in rat tubular hypoxia/reoxygenation injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 1691–1695, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]