Abstract

Cancer chemotherapeutic agents often have a narrow therapeutic index that challenges the maintenance of a safe and effective dose. Consistent plasma concentrations of a drug can be obtained by using a timed-release prodrug strategy. We reasoned that a ribonucleoside 3′-phosphate could serve as a pro-moiety that also increases the hydrophilicity of a cancer chemotherapeutic agent. Herein, we report an efficient route for the synthesis of the prodrug uridine 3′-(4-hydroxytamoxifen phosphate) (UpHT). UpHT demonstrates timed-released activation kinetics with a half-life of approximately 4 h at the approximate plasma concentration of human pancreatic ribonuclease (RNase 1). MCF-7 breast cancer cells treated with UpHT showed decreased proliferation upon coincubation with RNase 1, consistent with the release of the active drug—4-hydroxytamoxifen. These data demonstrate the utility of a human plasma enzyme as a useful activator of a prodrug.

Keywords: human pancreatic ribonuclease, 4-hydroxytamoxifen, pharmacokinetics, plasma, tamoxifen, timed-release

Many drug candidates have demonstrable therapeutic potential in vitro but fail in vivo because of poor pharmacokinetic behavior.1,2 The dosing of chemotherapeutic agents for cancer, in particular, is made difficult by narrow therapeutic indices.3,4 Following parenteral administration of a drug, there is a spike in drug plasma concentration, followed by a slow decline in concentration as the drug is eliminated or metabolized, complicating maintenance of the drug at a beneficial concentration.3,5 Timed-release prodrug technology provides one potential means to overcome this problem. A pro-moiety renders the drug inactive until liberation by an enzyme-catalyzed or nonenzymatic process. Ideally, such timed release modulates near-toxic peaks or near-ineffective troughs in the concentration of active drug in plasma.1,3,5−7 Although many pro-moieties exist,1−7 few provide timed release in plasma.

We sought a pro-moiety that would not only inactivate the parent drug but also be released during catalysis by an endogenous plasma enzyme. Fulfilling these criteria is difficult, as few enzymes have adequate plasma concentrations and many that do have high specificity for a native substrate. Human pancreatic ribonuclease (RNase 1;8 EC 3.1.27.5) is an exception. Contrary to its name, RNase 1 is expressed in tissues other than pancreas9 and circulates in human plasma at a concentration of ∼0.4 mg/L.10,10b Moreover, like its renowned homologue bovine pancreatic ribonuclease (RNase A11,12), RNase 1 catalyzes the cleavage of RNA by a transphosphorylation reaction13−15 and has little specificity for its leaving group.16−20 This promiscuity is the basis for the tumor-targeted activation of a phenolic nitrogen mustard from a ribonucleoside 3′-phosphate prodrug using an antibody–RNase 1 variant in an antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy (ADEPT) strategy.20

Because of the promiscuous activity of ribonucleases, we reasoned that a chemotherapeutic drug condensed with a ribonucleoside 3′-phosphate pro-moiety would be released upon catalysis by RNase 1. We were aware that the use of a ribonucleoside 3′-phosphate as a pro-moiety would be facilitated by extant, highly optimized phosphoramidite chemistry,21,22 making the prodrug readily accessible on a laboratory or industrial scale. A pendant ribonucleoside 3′-phosphate could render inactive a small-molecule drug by hindering the interaction with its target. The hydrophilicity of a ribonucleoside 3′-phosphate could impart improved pharmacokinetics to hydrophobic drugs.23 Additionally, small molecules with anionic groups are endowed with reduced rates of cytosolic uptake and glomerular filtration.24−31

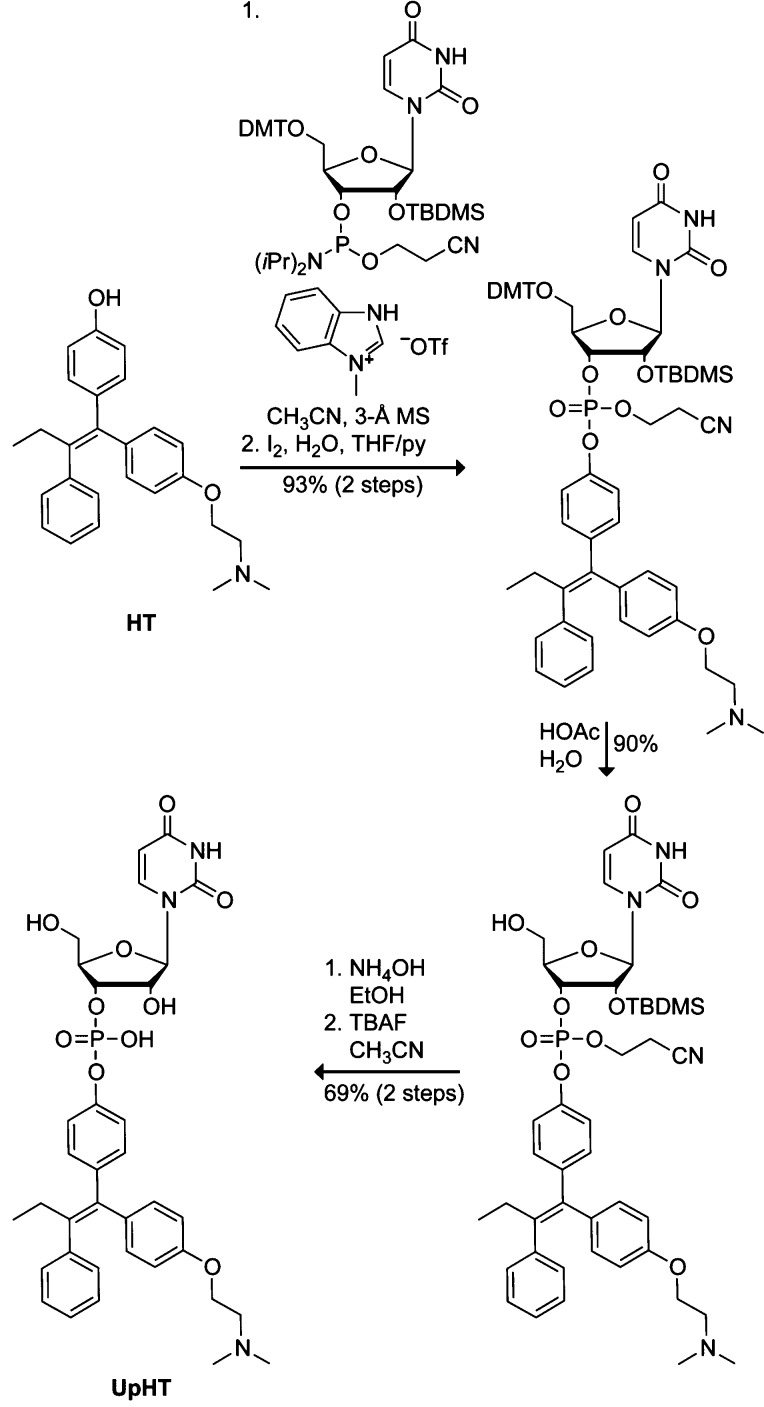

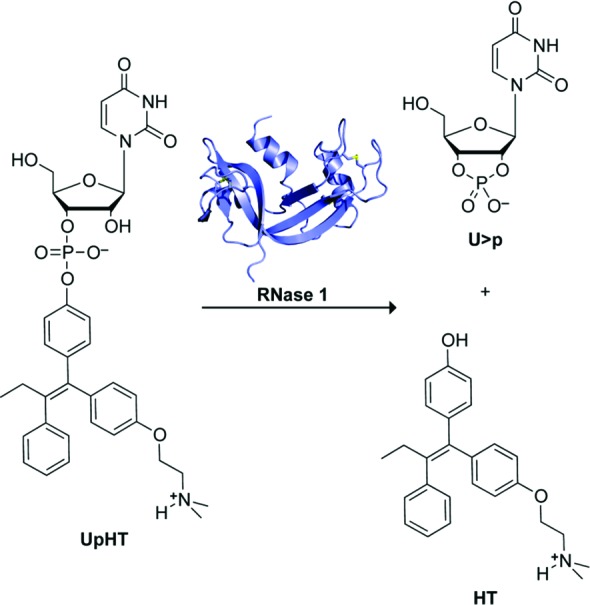

For our proof-of-concept studies, we chose the model parent drug 4-hydroxytamoxifen (HT). HT is the activated form of tamoxifen (oxidized by cytochrome P450 enzymes32) and is significantly more potent than tamoxifen as an antiproliferative agent against breast cancer cells.33 Tamoxifen acts as an antiestrogen and is one of the most commonly used hormonal drugs for the prevention and treatment of breast cancer.34,35 Unfortunately, tamoxifen can have off-target effects and is linked to an increased risk (2–3%) of endometrial carcinoma and pulmonary embolism.36 Presumably, these side effects could be attenuated by delivering tamoxifen at a consistent, low dose.37−41 Tamoxifen-encapsulated liposomes have been developed for this purpose,41 but liposomal delivery has, in general, demonstrated only modest efficacy in the clinic.42 Hence, we elected to attach HT to uridine 3′-phosphate and analyze the activation of this model prodrug by RNase 1 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scheme showing the cleavage of prodrug UpHT by RNase 1 to yield uridine 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate (U>p) and HT.

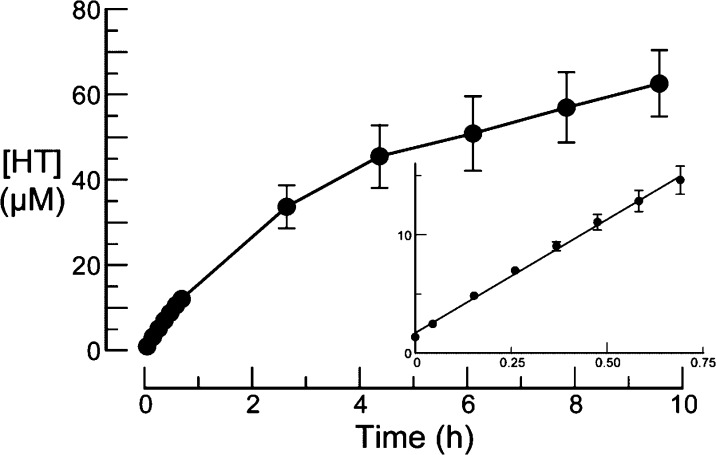

Uridine 3′-(4-hydroxytamoxifen phosphate) (UpHT) was synthesized in five steps from commercially available HT (≥70% Z isomer, which is the more active form43,44) and uridine phosphoramidite (Scheme 1). Briefly, HT was coupled to uridine phosphoramidite by using N-methylbenzimidazolium triflate as a catalyst.45 The coupled product was oxidized with iodine and deprotected stepwise. The final product was purified by reverse-phase HPLC on C18 resin to provide UpHT in an overall yield of 58%.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of UpHT.

We expected the uridine 3′-phosphate moiety of UpHT to endow the prodrug with greater hydrophilicity than the parent drug, which could improve pharmacokinetic behavior. To investigate this issue, we calculated the partition (log P) and distribution (log D) coefficients of UpHT and HT.46 The calculated log P and log D values of UpHT were indeed significantly lower than those of the parent drug HT (Table 1), indicative of increased hydrophilicity.

Table 1. Calculated Partition and Distribution Coefficients of HT and UpHT46.

| coefficient | HT | UpHT |

|---|---|---|

| log P (nonionized) | 6.05 | 3.88 |

| log P (ionized) | 2.55 | –2.00 |

| log D (pH = 7.4) | 4.66 | 0.12 |

| log D (pH = pIa) | 5.69 | –1.79 |

HT, pI = 9.01; UpHT, pI = 5.00.

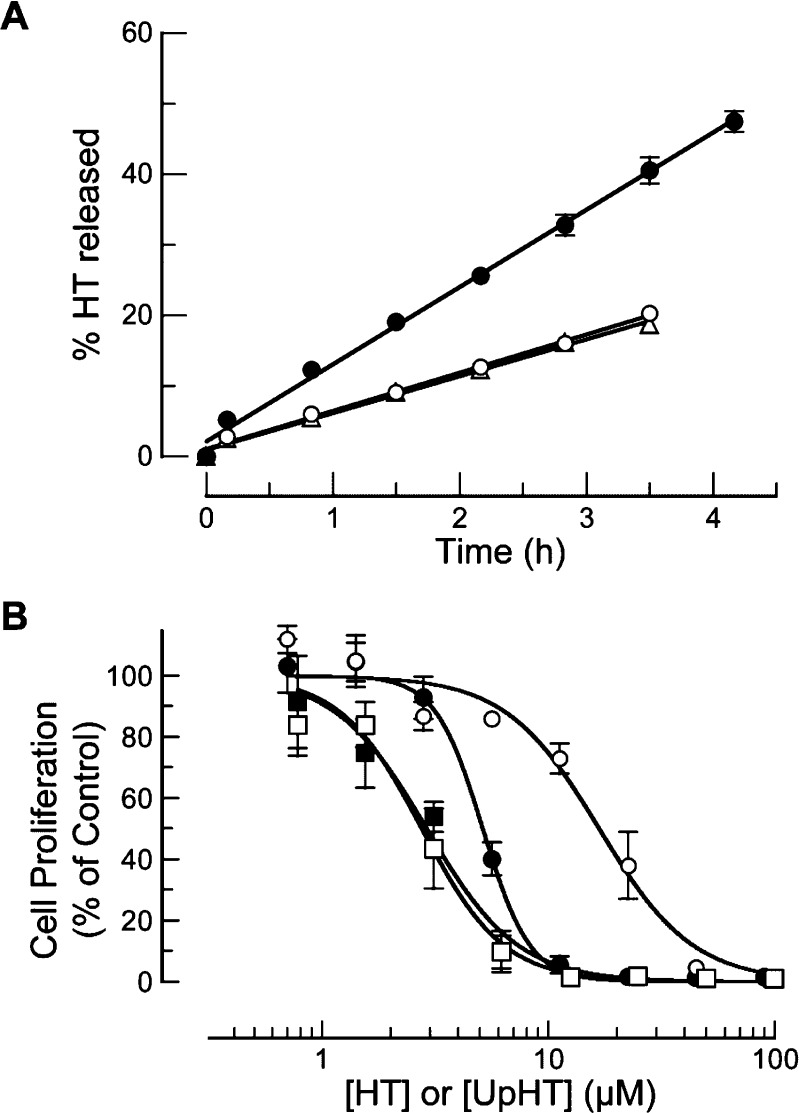

To be the basis for an effective timed-release prodrug strategy, the pro-moiety needs to be released by the activating enzyme over time. Hence, we assessed the RNase 1-catalyzed rate of HT-release from UpHT. To do so, RNase 1 (final concentration: ∼0.15 μg/mL) was added to 0.10 M 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES)–NaOH buffer, pH 6.0, containing NaCl (0.10 M) and UpHT (0.090 mM).47−49 The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C, and aliquots were withdrawn at known times and assayed for HT by HPLC. Under these conditions, which are typical for assays of ribonucleolytic activity,11,47 HT was released with a half-life of ∼4 h (Figure 2). Importantly, UpHT was stable in the absence of RNase 1; after 11 h at 37 °C, <6% of UpHT had degraded to HT.

Figure 2.

Progress curve for the release of HT from UpHT (0.090 mM) by RNase 1 (∼0.15 μg/mL) in 0.10 M MES–NaOH buffer, pH 6.0, containing NaCl (0.10 M) at 37 °C. Inset: t < 1 h.

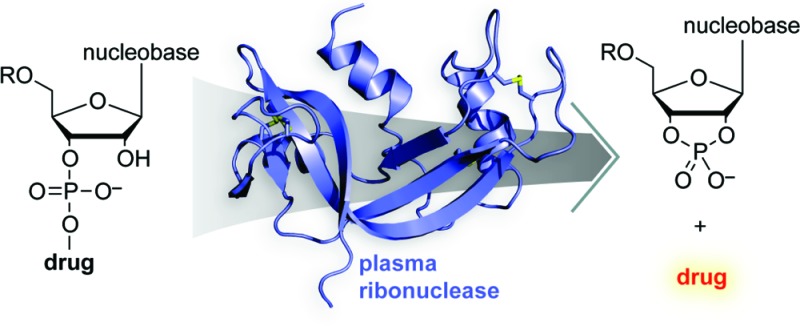

To assess the unmasking of UpHT under more physiological conditions, HT release from UpHT was monitored in cell culture medium (Figure 3A). In medium without added ribonucleases, HT was released with a half-life of ∼9 h. To validate that UpHT is inherently unstable at pH 7.4 (as opposed to the medium containing contaminating ribonucleases), the stability of UpHT was assessed in ribonuclease-free 0.10 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing NaCl (0.10 M). Again, the half-life was ∼9 h. The instability of UpHT at pH 7.4 is consistent with HT being a good leaving group, as its hydroxyl group has pKa ∼9.3.46 By comparison, the P–O5′ bond in RNA has a half-life of 4 years.51

Figure 3.

Stability of UpHT and effect of UpHT on the proliferation of MCF-7 cells. All data points are the means (±SEs) of separate experiments carried out in triplicate. (A) Progress curves for the release of HT from UpHT (40 μM) at 37 °C in ribonuclease-free 0.10 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing NaCl (0.10 M) (△; t1/2 = 9.4 h) and serum-free50 medium in the absence (○; t1/2 = 9.0 h) and presence (●; t1/2 = 4.4 h) of RNase 1 (0.4 μg/mL). (B) Proliferation of MCF-7 cells in serum-free50 medium, monitored by the incorporation of [methyl-3H]thymidine into cellular DNA. UpHT in the absence (○; IC50 = 16.7 ± 0.8 μM) and presence (●; IC50 = 5.2 ± 0.2 μM) of RNase 1 (6.2 μg/mL). HT in the absence (□; IC50 = 2.7 ± 0.1 μM) and presence (■; IC50 = 2.7 ± 0.4 μM) of RNase 1.

To demonstrate the efficacy of UpHT in cellulo, we monitored its effect on the proliferation of MCF-7 breast cancer cells, which are known to be vulnerable to HT.33 UpHT was made more antiproliferative by the presence of added RNase 1 (Figure 3B), indicating that UpHT is a ribonuclease-activatable prodrug. Thus, we have demonstrated proof-of-concept for a prodrug strategy that employs a human plasma enzyme to release a cancer chemotherapeutic agent in a timed-release manner (Figure 1).

In addition to the attributes evident in UpHT, the RNase 1/ribonucleoside 3′-phosphate prodrug system has versatile modularity. For example, the leaving group need not be an aryloxy group. Pancreatic-type ribonucleases catalyze the cleavage of P–O bonds to alkoxy groups, which could include a self-immolative linker to an amino group.4 RNase 1 is known to cleave RNA faster after pyrimidine than purine nucleobases.52 Hence, cytidine- and uridine-masked drugs are likely to be activated more rapidly than adenosine- and guanosine-masked drugs. In addition, synergistic drugs could be conjugated to different ribonucleoside 3′-phosphates to achieve simultaneous release of drugs at desired concentrations. These same effects could be used to optimize simultaneous plasma concentrations of chemoprotective drugs and chemotherapeutic drugs. The pharmacokinetics of the drug could be tuned further by modification of the ribose 5′-hydroxyl group. For instance, this hydroxyl group could be PEGylated to enhance serum half-life, extended with additional nucleoside 3′-phosphates to increase hydrophilicity, or alkylated with the intent of increasing hydrophobicity.53,53b

Finally, we note that nucleoside 3′-phosphate pro-moieties could impart selective activation of chemotherapeutic agents near tumor sites. Although RNase 1 was employed herein due to its abundance in plasma,8,9,54,55 RNase 1 homologues might also activate prodrugs like UpHT in situ.8 One such homologue is eosinophil-derived neurotoxin (RNase 2), which is carried and released by eosinophils.8 These cells are known to accumulate and degranulate at tumor sites.56−58 We anticipate that, akin to prodrug monotherapy (PMT) in which prodrugs are activated by endogenous enzymes found in abundance near tumors,59 a prodrug strategy reliant on RNase 2 could be used to generate active drugs at adventitious sites. Studies to probe the versatility of the RNase 1/ribonucleoside 3′-phosphate prodrug system are underway in our laboratory.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge M. L. Hornung for early contributions to this work.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- HT

hydroxytamoxifen

- MES

2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid

- RNase 1

human pancreatic ribonuclease

- U>p

uridine 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate

- UpHT

uridine 3′-(4-hydroxytamoxifen phosphate)

Supporting Information Available

Analytical data and experimental protocols. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

∥ These authors contributed equally to this work.

This work was supported by Grant R01 CA073808 (NIH). N.A.M. was supported by the postdoctoral fellowship F32 GM096712 (NIH). M.J.P. was supported by Molecular and Cellular Pharmacology Training Grant T32 GM008688 (NIH) and predoctoral fellowship 09PRE2260125 (American Heart Association). This study made use of the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison, which is supported by NIH Grants P41RR02301 (BRTP/NCRR) and P41GM66326 (NIGMS). Additional equipment was purchased with funds from the University of Wisconsin, the NIH (RR02781, RR08438), the NSF (DMB-8415048, OIA-9977486, BIR-9214394), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Wang B.; Siahaan T.; Soltero R.. Drug Delivery: Principles and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rautio J.; Kumpulainen H.; Heimbach T.; Oliyai R.; Oh D.; Jarvinen T.; Savolainen J. Prodrugs: Design and clinical applications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2008, 7, 255–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennaro A. R.Remington: The Science and Practice of Pharmacy, 21st ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kratz F.; Muller I. A.; Ryppa C.; Warnecke A. Prodrug strategies in anticancer chemotherapy. ChemMedChem 2008, 3, 20–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer R. New methods of drug delivery. Science 1990, 249, 1527–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa B.; Mayer J. M.. Hydrolysis in Drug and Prodrug Metabolism: Chemistry, Biochemistry, and Enzymology; Wiley-VCH: Zürich, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. M.Drug Delivery Systems in Cancer Therapy; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sorrentino S. The eight human “canonical” ribonucleases: Molecular diversity, catalytic properties, and special biological actions of the enzyme proteins. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 2194–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su A. I.; Wiltshire T.; Batalov S.; Lapp H.; Ching K. A.; Block D.; Zhang J.; Soden R.; Hayakawa M.; Kreiman G.; Cooke M. P.; Walker J. R.; Hogenesch J. B. A gene atlas of the mouse and human protein-encoding transcriptomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004, 101, 6062–6067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The ribonucleolytic activity in serum is attributable to RNase 1. Its concentration there is 156 units/mL with 1 unit of activity arising from 2.6 ng of enzyme.Weickmann J. L.; Olson E. M.; Glitz D. G. Immunological assay of pancreatic ribonuclease in serum as an indicator of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 1984, 44, 1682–1687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Also seeLandré J. B. P.; Hewett P. W.; Olivot J.-M.; Friedl P.; Sachinidis A.; Moenner M. Human endothelial cells selectively express large amounts of pancreatic-type ribonuclease (RNase 1). J. Cell. Biochem. 2002, 86, 540–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raines R. T. Ribonuclease A.. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 1045–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuchillo C. M.; Nogués M. V.; Raines R. T. Bovine pancreatic ribonuclease: Fifty years of the first enzymatic reaction mechanism. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 7835–7841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham R.; Smith J. D. The structure of ribonucleic acids. 1. Cyclic nucleotides produced by ribonuclease and by alkaline hydrolysis. Biochem. J. 1952, 52, 552–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuchillo C. M.; Parés X.; Guasch A.; Barman T.; Travers F.; Nogués M. V. The role of 2′,3′-cyclic phosphodiesters in the bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A catalysed cleavage of RNA: Intermediates or products?. FEBS Lett. 1993, 333, 207–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. E.; Venegas F. D.; Raines R. T. Energetics of catalysis by ribonucleases: Fate of the 2′,3′-cyclic phosphodiester intermediate. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 7408–7414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis A. M.; Regan A. C.; Williams A. Experimental charge measurement at leaving oxygen in the bovine ribonuclease A catalyzed cyclization of uridine 3′-phosphate aryl esters. Biochemistry 1988, 27, 9042–9047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witmer M. R.; Falcomer C. M.; Weiner M. P.; Kay M. S.; Begley T. P.; Ganem B.; Scheraga H. A. U-3′-BCIP: A chromogenic substrate for the detection of RNase A in recombinant DNA expression systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991, 19, 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. E.; Raines R. T. Value of general acid–base catalysis to Ribonuclease A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 5467–5468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowell J. K.; Widlanski T. S.; Kutateladze T. G.; Raines R. T. Mechanism-based inactivation of ribonuclease A. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 6930–6936. [Google Scholar]

- Taylorson C. J.; Eggelte H. J.; Tarragona-Fiol A.; Rabin B. R.; Boyle F. T.; Hennam J. F.; Blakey D. C.; Marsham P. R.; Heaton D. W.; Davies D. H.; Slater A. M.; Hennequin L. F. A. Chemical compounds. U.S. Patent No. 5985281, 1999.

- Beaucage S. L.; Caruthers M. H. Deoxynucleoside phosphoramidites—A new class of key intermediates for deoxypolynucleotide synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981, 22, 1859–1862. [Google Scholar]

- Caruthers M. H. A brief review of DNA and RNA chemical synthesis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2011, 39, 575–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stella V. J.; Nti-Addae K. W. Prodrug strategies to overcome poor water solubility. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2007, 59, 677–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner C. R.; Iyer V. V.; McIntee E. J. Pronucleotides: Toward the in vivo delivery of antiviral and anticancer nucleotides. Med. Res. Rev. 2000, 20, 417–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micklefield J. Backbone modification of nucleic acids: Synthesis, structure and therapeutic applications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2001, 8, 1157–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz C. Prodrugs of biologically active phosphate esters. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003, 11, 885–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasi C.; Quelever G.; Burlet S.; Garino C.; Souard F.; Kraus J. L. New antiviral nucleoside prodrugs await application. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 1825–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venturoli D.; Rippe B. Ficoll and dextran vs. globular proteins as probes for testing glomerular permselectivity: Effects of molecular size, shape, charge, and deformability. Am. J. Physiol.-Renal 2005, 288, F605–F613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens D. E. 3rd; Peppas N. A. Opsonization, biodistribution, and pharmacokinetics of polymeric nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. 2006, 307, 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecker S. J.; Erion M. D. Prodrugs of phosphates and phosphonates. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 2328–2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandazhinskaya A.; Matyugina E.; Shirokova E. Anti-HIV therapy with AZT prodrugs: AZT phosphonate derivatives, current state and prospects. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2011, 6, 701–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desta Z.; Ward B. A.; Soukhova N. V.; Flockhart D. A. Comprehensive evaluation of tamoxifen sequential biotransformation by the human cytochrome P450 system in vitro: Prominent roles for CYP3A and CYP2D6. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 310, 1062–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coezy E.; Borgna J. L.; Rochefort H. Tamoxifen and metabolites in MCF7 cells: Correlation between binding to estrogen receptor and inhibition of cell growth. Cancer Res. 1982, 42, 317–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Regan R. M.; Jordan V. C. The evolution of tamoxifen therapy in breast cancer: Selective oestrogen-receptor modulators and downregulators. Lancet Oncol. 2002, 3, 207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powles T. J. Anti-oestrogenic chemoprevention of breast cancer-the need to progress. Eur. J. Cancer 2003, 39, 572–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B.; Costantino J. P.; Wickerham D. L.; Cecchini R. S.; Cronin W. M.; Robidoux A.; Bevers T. B.; Kavanah M. T.; Atkins J. N.; Margolese R. G.; Runowicz C. D.; James J. M.; Ford L. G.; Wolmark N. Tamoxifen for the prevention of breast cancer: Current status of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2005, 97, 1652–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman L.; Beelen M. L.; Gallee M. P.; Hollema H.; Benraadt J.; van Leeuwen F. E. Risk and prognosis of endometrial cancer after tamoxifen for breast cancer. Comprehensive cancer centres' ALERT group. Assessment of liver and endometrial cancer risk following tamoxifen. Lancet 2000, 356, 881–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decensi A.; Robertson C.; Viale G.; Pigatto F.; Johansson H.; Kisanga E. R.; Veronesi P.; Torrisi R.; Cazzaniga M.; Mora S.; Sandri M. T.; Pelosi G.; Luini A.; Goldhirsch A.; Lien E. A.; Veronesi U. A randomized trial of low-dose tamoxifen on breast cancer proliferation and blood estrogenic biomarkers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003, 95, 779–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitseva O.; Flockhart D. A.; Jin Y.; Varghese S.; Freedman J. E. The effects of tamoxifen and its metabolites on platelet function and release of reactive oxygen intermediates. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005, 312, 1144–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veronesi U.; Maisonneuve P.; Decensi A. Tamoxifen: An enduring star. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2007, 99, 258–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layek B.; Mukherjee B. Tamoxifen citrate encapsulated sustained release liposomes: Preparation and evaluation of physicochemical properties. Sci. Pharm. 2010, 78, 507–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen T. L.; Jensen S. S.; Jorgensen K. Advanced strategies in liposomal cancer therapy: Problems and prospects of active and tumor specific drug release. Prog. Lipid Res. 2005, 44, 68–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzenellenbogen J. A.; Carlson K. E.; Katzenellenbogen B. S. Facile geometric isomerization of phenolic non-steroidal estrogens and antiestrogens: Limitations to the interpretation of experiments characterizing the activity of individual isomers. J. Steroid Biochem. 1985, 22, 589–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C. S.; Langan-Fahey S. M.; McCague R.; Jordan V. C. Structure–function relationships of hydroxylated metabolites of tamoxifen that control the proliferation of estrogen-responsive T47D breast cancer cells in vitro. Mol. Pharmacol. 1990, 38, 737–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa Y.; Kawai R.; Hirata A.; Sugimoto J. I.; Kataoka M.; Sakakura A.; Hirose M.; Noyori R. Acid/azole complexes as highly effective promoters in the synthesis of DNA and RNA oligomers via the phosphoramidite method. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 8165–8176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calculator Plugins were used for structure property prediction and calculation. Marvin 5.4.1.1; ChemAxon: Budapest, Hungary, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kelemen B. R.; Klink T. A.; Behlke M. A.; Eubanks S. R.; Leland P. A.; Raines R. T. Hypersensitive substrate for ribonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 3696–3701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B. D.; Soellner M. B.; Raines R. T. Potent inhibition of ribonuclease A by oligo(vinylsulfonic acid). J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 20934–20938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. J.; McCoy J. G.; Bingman C. A.; Phillips G. N., Jr.; Raines R. T.; Phillips G. N. Inhibition of human pancreatic ribonuclease by the human ribonuclease inhibitor protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 368, 434–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serum contains both contaminating ribonucleases and albumin, which binds and thus sequesters HT.Bourassa P.; Dubeau S.; Maharvi G. M.; Fauq A. H.; Thomas T. J.; Tajmir-Riahi H. A. Binding of antitumor tamoxifen and its metabolites 4-hydroxytamoxifen and endoxifen to human serum albumin. Biochimie 2011, 93, 1089–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. E.; Kutateladze T. G.; Schuster M. C.; Venegas F. D.; Messmore J. M.; Raines R. T. Limits to catalysis by ribonuclease A. Bioorg. Chem. 1995, 23, 471–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrentino S.; Libonati M. Human pancreatic-type and nonpancreatic-type ribonucleases: A direct side-by-side comparison of their catalytic properties. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1994, 312, 340–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UpHT or its derivatives could provide exquisite control of gene expression in transgenic mice via the widely used Cre recombinase–estrogen receptor system.; Fell R.; Brocard J.; Mascrez B.; LeMeur M.; Metzger D.; Chambon P. Ligand-activated site-specific recombination in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996, 93, 10887–10890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S.; McMahon A. P. Efficient recombination in diverse tissues by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre: A tool for temporally regulated gene activiation/inactivation in the mouse. Dev. Biol. 2002, 244, 305–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weickmann J. L.; Olson E. M.; Glitz D. G. Immunological assay of pancreatic ribonuclease in serum as an indicator of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 1984, 44, 1682–1687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potenza N.; Salvatore V.; Migliozzi A.; Martone V.; Nobile V.; Russo A. Hybridase activity of human ribonuclease-1 revealed by a real-time fluorometric assay. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 2906–2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munitz A.; Levi-Schaffer F. Eosinophils: 'New' roles for 'old' cells. Allergy 2004, 59, 268–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormier S. A.; Taranova A. G.; Bedient C.; Nguyen T.; Protheroe C.; Pero R.; Dimina D.; Ochkur S. I.; O’Neill K.; Colbert D.; Lombari T. R.; Constant S.; McGarry M. P.; Lee J. J.; Lee N. A. Pivotal advance: Eosinophil infiltration of solid tumors is an early and persistent inflammatory host response. J. Leukocyte Biol. 2006, 79, 1131–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotfi R.; Lee J. J.; Lotze M. T. Eosinophilic granulocytes and damage-associated molecular pattern molecules (DAMPs): Role in the inflammatory response within tumors. J. Immunother. 2007, 30, 16–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosslet K.; Straub R.; Blumrich M.; Czech J.; Gerken M.; Sperker B.; Kroemer H. K.; Gesson J. P.; Koch M.; Monneret C. Elucidation of the mechanism enabling tumor selective prodrug monotherapy. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 1195–1201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.