Abstract

p66Shc, a longevity adaptor protein, is demonstrated as a key regulator of reactive oxygen species (ROS) metabolism involved in aging and cardiovascular diseases. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) stimulates endothelial cell (EC) migration and proliferation primarily through the VEGF receptor-2 (VEGFR2). We have shown that ROS derived from Rac1-dependent NADPH oxidase are involved in VEGFR2 autophosphorylation and angiogenic-related responses in ECs. However, a role of p66Shc in VEGF signaling and physiological responses in ECs is unknown. Here we show that VEGF promotes p66Shc phosphorylation at Ser36 through the JNK/ERK or PKC pathway as well as Rac1 binding to a nonphosphorylated form of p66Shc in ECs. Depletion of endogenous p66Shc with short interfering RNA inhibits VEGF-induced Rac1 activity and ROS production. Fractionation of caveolin-enriched lipid raft demonstrates that p66Shc plays a critical role in VEGFR2 phosphorylation in caveolae/lipid rafts as well as downstream p38MAP kinase activation. This in turn stimulates VEGF-induced EC migration, proliferation, and capillary-like tube formation. These studies uncover a novel role of p66Shc as a positive regulator for ROS-dependent VEGFR2 signaling linked to angiogenesis in ECs and suggest p66Shc as a potential therapeutic target for various angiogenesis-dependent diseases.

Keywords: reactive oxygen species, vascular endothelial growth factor

angiogenesis is involved in normal and postnatal development as well as reparative neovascularization that is associated with wound healing, ischemic heart and limb diseases, and chronic inflammatory diseases such as atherosclerosis. In endothelial cells (ECs), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) induces angiogenesis by stimulating EC migration and proliferation primarily through the autophosphorylation of VEGF receptor type-2 (VEGFR2, KDR/Flk1; VEGFR2-pY), which initially occurs in part in caveolae/lipid rafts (19, 23, 32). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) function as key signaling molecules to mediate various biological responses such as cell migration, proliferation, and gene expression (11, 15, 37, 47). We and others (7, 48) reported that ROS derived from NADPH oxidase play an important role in VEGFR2 signaling and angiogenic responses in ECs, as well as ischemia-induced neovascularization in vivo (9, 17, 42, 45). However, the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood.

The adaptor protein p66Shc is a life span determinant that integrates metabolic and longevity pathways and a key regulator for oxidative stress-mediated aging and cardiovascular diseases (3, 8, 10, 13, 26, 28, 29, 36). The Shc protein is expressed as three isoforms with relative molecular mass of 46, 52, and 66 kDa (34). They consist of a phosphotyrosine binding domain (PTB), a collagen homology domain (CH1), and a C-terminal Src homology 2 domain (SH2). In addition, p66Shc contains a unique N-terminal collagen homology domain (CH2) that includes a Ser36. p66Shc phosphorylation at Ser36 triggers a cascade of events leading to an increase in ROS production (8, 14, 26, 35). Mice lacking p66Shc display prolonged life span, reduced production of intracellular oxidants, and increased resistance to oxidative stress-induced apoptosis (26). Accordingly, the majority of studies using p66Shc−/− mice have defined the pathophysiological role of p66Shc in cardiovascular disease where ROS represent a substantial triggering component (3, 8, 10, 13, 28, 36). By contrast, recent report (27) using isolated p66Shc−/− T cells shows that p66Shc is required for the angiogenic response stimulated by hypoxia.

Here we test the hypothesis that p66Shc may be involved in ROS-dependent VEGF signaling linked to angiogenesis in ECs. The present study demonstrates that VEGF stimulation increases Ser36-phosphorylation of p66Shc in human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) at least in part through ERK, JNK, or PKC. We also found that VEGF promotes Rac1 association with a nonphosphorylated form of p66Shc and that p66Shc is involved in VEGF-induced Rac1 activation and ROS production, which promotes VEGFR2 autophosphorylation in caveolae/lipid rafts and p38MAPK activation. This in turn contributes to VEGF-induced angiogenic-related responses in ECs. These studies are the first to demonstrate the physiological function of p66Shc involved in VEGF-induced ROS production and VEGFR2-mediated redox signaling linked to angiogenesis in ECs.

METHODS

Materials.

Antibodies to VEGFR2, phosphotyrosine (pY99), and paxillin were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibody to phospho-Ser36-p66Shc was from Calbiochem. Antibodies to phospho-VEGFR2 (pY1175), phospho-p38MAPK, and phospho-ERK1/2 were from Cell Signaling. Anti-caveolin-1 and Shc antibodies were from BD Biosciences. Human recombinant VEGF165 was from R&D Systems. Oligofectamine and Opti-MEMI reduced-serum medium were from Invitrogen. Other materials were purchased from Sigma.

Cell culture.

HUVECs were grown in Endo-Gro (Millipore) containing 5% FBS.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

Growth-arrested HUVECs were stimulated with VEGF (20 ng/ml), and cells were lysed in lysis buffer at pH 7.4 (in mM: 50 HEPES, 5 EDTA, and 100 NaCl), 1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitors (10 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 mmol/l PMSF, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin), and phosphatase inhibitors (in mmol/l: 50 sodium fluoride, 1 sodium orthovanadate, and 10 sodium pyrophosphate). Cell lysates were used for immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting, as described previously (49).

H2O2 measurement.

HUVECs grown on glass coverslips were incubated with 20 μM 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, acetyl ester (CM-H2DCF-DA; Invitrogen) for 6 min at 37°C and then Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI was dropped on them. Cells were observed by confocal microscopy using the same exposure condition in each experiment. Relative DCF-DA fluorescence intensity with DAPI-positive cells was recorded and analyzed using Image J.

Sucrose gradient fractionation.

Caveolae/lipid rafts fractions were separated, as described previously (32, 38). Briefly, HUVECs (5.0 × 107 cells) were homogenized in a solution containing 0.5 M sodium carbonate (pH 11), 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and protease inhibitors. The homogenates were adjusted to 45% sucrose by addition of 90% sucrose in a buffer containing 25 mM MES (pH 6.5) and 0.15 M NaCl. A 5–35% discontinuous sucrose gradient was formed above and centrifuged at 39,000 rpm for 16–20 h in a Beckman SW-40Ti rotor. From the top of the tube, 13 fractions were collected, and an equal volume from each fraction was subjected to immunoblotting. To quantify the protein expression levels in caveolae/lipid rafts and noncaveolae/lipid rafts fractions, equal volume of fractions 4–5 were combined for caveolae/lipid rafts and fractions 9–13 were combined for noncaveolae/lipid rafts.

Short interfering RNA transfection.

HUVECs were grown to 40% confluence in 100-mm dishes and transfected with 10 nM control short intefering (si)RNA (from Ambion) and p66Shc siRNA (sense: 5′-GAAUGAGUCUCUGUCAUCGCU-3′ and antisense: 5′-CGAUGACAGAGACUCAUUCCG-3′ within the N;terminal CH2 domain, which is not found in p52 and p46 Shc) using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen), as described previously (52). Cells were used for experiments at 48 h after transfection.

Rac1 activity assay.

Rac1 activation was measured using a G-LISA Rac activation assay kit (Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, serum-starved HUVECs were stimulated with VEGF (20 ng/ml) for 5 min. Cell lysates were incubated on Rac-GTP affinity plates for 30 min at 4°C, and Rac1 activation was measured by luminometry.

Modified Boyden chamber migration assay.

Migration assays using a modified Boyden chamber method were conducted in 24-well Transwell chambers as described previously (49).

Wound scratch assay.

HUVEC were grown to confluence in sixwell plates, and a scratch was applied with a plastic pipette tip to mimic wound injury. After 24 h in a 37°C CO2 incubator in growth arrest medium containing 50 ng/ml VEGF, migrating cells were assessed by the closure of the wound area, as described previously (21, 52).

Cell proliferation assay.

HUVECs (105 cells) were seeded in sixwell plates, and cell number with and without VEGF in 0.2% FBS containing culture medium was determined by counting with a hemocytometer as described before (49, 52).

Capillary network formation assay.

HUVECs transfected with control siRNA or p66Shc siRNA were seeded on top of the thick growth factor-reduced Matrigel-coated wells (BD Biosciences) and incubated for 6 h at 37°C. Images were taken with a Nikon digital camera, and eight random fields per well were analyzed.

Statistical analysis.

Results are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical significance was assessed by Student's paired two-tailed t-test or ANOVA on untransformed data, followed by comparison of group averages by contrast analysis using the Super ANOVA statistical program (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA). A P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

VEGF increases Ser36 phosphorylation of p66Shc through ERK/JNK or PKC in ECs.

To address the role of p66Shc in VEGF signaling, we examined the effect of VEGF on Ser36 phosphorylation of p66Shc (pS36-p66Shc) in HUVECs. Figure 1A shows that VEGF increased pS36-p66Shc within 5 min, which peaked at 15 min and remained above baseline for up to 60 min. We examined the upstream pathways mediating pS36-p66Shc formation by VEGF. Figure 1B shows that the MEK inhibitor PD98059, the JNK inhibitor SP600125, or the protein kinase C inhibitor GF109203X, but not the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 or the p38MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580, significantly inhibited VEGF-induced p66Shc phosphorylation. These results suggest that VEGF increases pS36-p66Shc at least in part through ERK/JNK or PKC in ECs.

Fig. 1.

VEGF increases Ser36 phosphorylation of p66Shc through ERK, JNK, or PKC in endothelial cells (ECs). A: human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) were stimulated with VEGF (20 ng/ml) for indicated minutes, and lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Shc antibody (Ab) or normal IgG (negative control) and immunoblotted (IB) with anti-phospho-Ser36-p66Shc (pS36-p66Shc) Ab or Shc Ab. (n = 3). Bottom: averaged data, expressed as fold change over basal (means ± SE). *P < 0.05 vs. control. B: HUVECs were pretreated with 20 μM LY294002 (LY), 10 μM SB203580 (SB), 20 μM PD98059 (PD), 20 μM SP600125 (SP), or 10 μM GF109203X (GF) for 30 min and stimulated with VEGF (20 ng/ml) for 15 min. Lysates were measured for pS36-p66Shc (n = 5). *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle +VEGF.

VEGF increases ROS production through p66Shc that associates with Rac1 and regulates its activation in ECs.

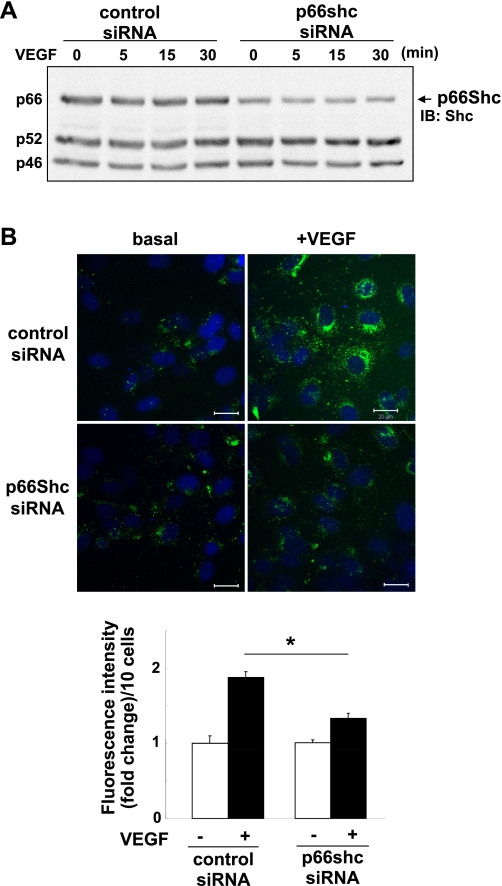

We next examined whether p66Shc is involved in VEGF-induced ROS production using DCF-DA that mainly detects intracellular H2O2 (32). Figure 2A shows that p66Shc siRNA selectively knocked down endogenous p66Shc protein expression without affecting the expression of p52Shc or p46Shc protein in HUVECs. Under this condition, p66Shc siRNA significantly inhibited VEGF-induced ROS production measured at 5 min (Fig. 2B) or 30 min (not shown). We confirmed that pretreatment of ECs with polyethylene glycol-catalase before loading DCF-DA abolished the basal and VEGF-induced fluorescence signals, as reported previously (32).

Fig. 2.

p66Shc is involved in VEGF-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in ECs. A: Western blots analysis for p66Shc in HUVECs after p66Shc short interfering (si)RNA treatment for 48 h. Lysates were immunoblotted with anti-total Shc Ab, and the bands of p66Shc are shown at 66 kDa. B, top: dichlorofluorescein (DCF) fluorescence with DAPI staining was measured by confocal microscopy in HUVECs transfected with control or p66Shc siRNAs with or without 20 ng/ml VEGF simulation for 5 min. B, bottom: averaged data of DCF fluorescence intensity (fold change)/10 cells (n = 3). *P < 0.05.

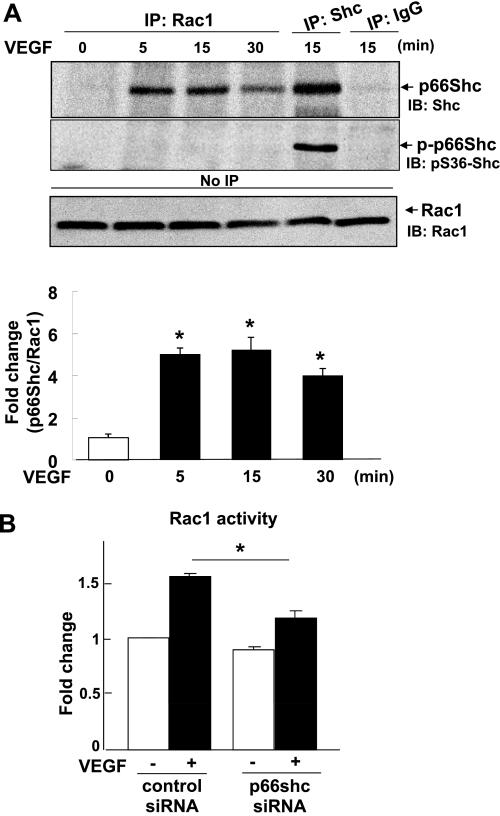

Since we previously demonstrated that VEGF-induced ROS production is dependent on Rac1, a cytosolic component of NADPH oxidase, we examined whether p66Shc binds to Rac1 and/or involved in VEGF-induced Rac1 activation. Figure 3A using coimmunoprecipitation analysis shows that VEGF stimulation increased association of Rac1 with p66Shc within 5 min, which continued above basal levels for ≥30 min. Rac1 immunoprecipitates failed to bind to pS36-p66Shc, indicating that Rac1 binds to nonphosphorylated form of p66Shc. Figure 3B shows that VEGF-induced Rac1 activation was significantly inhibited by p66Shc siRNA. These results suggest that VEGF promotes p66Shc association with Rac1, which may be required for activation of Rac1 and subsequent ROS production in ECs.

Fig. 3.

VEGF stimulates p66Shc association with Rac1 and its activation through p66Shc in ECs. A: HUVECs were stimulated with VEGF (20 ng/ml) for indicated minutes. Cell lysates were IP with anti-Rac1 or Shc Abs or normal IgG, and IB with anti-Shc or pS36-p66Shc Abs. Lysates without IP (No IP) were IB with anti-Rac1 Ab. A, bottom: averaged data for fold change in p66Shc-Rac1 association, expressed as -fold change over basal. *P < 0.05. B: Rac1 activities were measured in HUVECs transfected with control or p66Shc siRNAs with or without 20 ng/ml VEGF stimulation for 5 min (n = 3). *P < 0.05.

p66Shc is involved in VEGF-induced VEGFR2 autophosphorylation in caveolae/lipid rafts and p38MAP kinase activation in ECs.

Since we previously demonstrated that ROS mediate VEGF-induced VEGFR2-pY, we next examined the role of p66Shc in VEGF signaling. Figure 4A shows that knockdown of p66Shc with siRNA significantly inhibited VEGF-induced VEGFR2-pY without affecting basal phosphorylation or total VEGFR2 protein expression. We next examined the role of p66Shc in major VEGFR2 downstream signaling events such as p38MAPK and ERK1/2 activation, which are key mediators of VEGF-induced EC migration and proliferation, respectively (24, 40). Figure 4B shows that p66Shc siRNA markedly inhibited VEGF-induced phosphorylation of p38MAPK without affecting ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

Fig. 4.

p66Shc is involved in VEGF-induced VEGFR2 autophosphorylation and p38MAPK activation in ECs. HUVECs were transfected with control or p66Shc siRNAs. A: cells were stimulated with VEGF (20 ng/ml) for 5 min, and lysates were IP with anti-VEGFR2 Ab and IB with anti-phospho-tyrosine (pTyr) Ab. Same lysates were IB with anti-VEGFR2 or Shc Abs (n = 4) *P < 0.05. B: cells were stimulated with VEGF for indicated minutes and lysates were IB with phospho-p38MAPK or phospho-ERK1/2 or p66Shc expression. *P < 0.05.

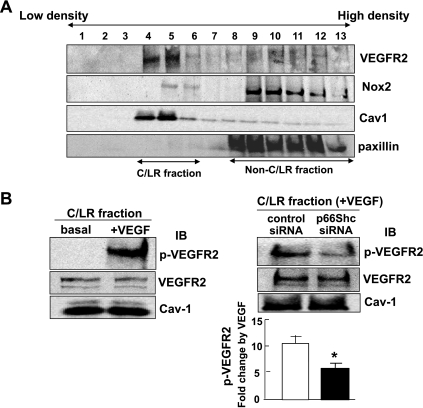

Since initial VEGFR2-pY increase occurs in part in caveolae/lipid rafts (19, 23, 32) where a fraction of NADPH oxidase is activated (25, 46, 47, 53, 55), we next examined the role of p66Shc in this localized VEGFR2 activation. Sucrose gradient fractionation confirmed that VEGFR2 and Nox2 were localized in caveolin-1-enriched, caveolae/lipid raft fractions 4–6 (Fig. 5A). Under this condition, VEGF stimulation rapidly increased VEGFR2-pY in caveolae/lipid rafts, which was significantly inhibited by p66Shc by siRNA (Fig. 5B). A parallel experiment confirmed that p66Shc siRNA specifically knocked down endogenous p66Shc protein expression in total lysates (not shown). These results suggest that p66Shc is involved in VEGFR2 autophosphorylation in caveolae/lipid rafts in ECs.

Fig. 5.

p66Shc is involved in VEGF-induced VEGFR2 autophosphorylation in caveolae/lipid rafts in ECs. A: sucrose gradient centrifugation was performed to isolate caveolae/lipid rafts (C/LR), equal volume of each fraction from top to bottom was IB with anti-VEGFR2, Nox2, caveolin-1, and paxillin (marker for non-C/LR) Abs. C/LR fraction were appeared in fractions 4–6. B, left: HUVECs were stimulated with or without VEGF (20 ng/ml) for 5 min, and followed by C/LR fractionation. Equal amounts of proteins from C/LR fraction were IB with anti-VEGFR2-pY1175, total VEGFR2, and caveolin-1 Abs (n = 3). B, right: HUVECs transfected with control or p66Shc siRNAs were stimulated with VEGF (20 ng/ml) for 5 min, and the C/LR fraction were IB with anti-VEGFR2-pY1175, total VEGFR2, and caveolin-1 Abs. B, bottom: averaged data, expressed as VEGF-induced fold change over basal in control siRNA-treated groups (means ± SE). *P < 0.05.

p66Shc is involved in VEGF-induced angiogenic related responses in ECs.

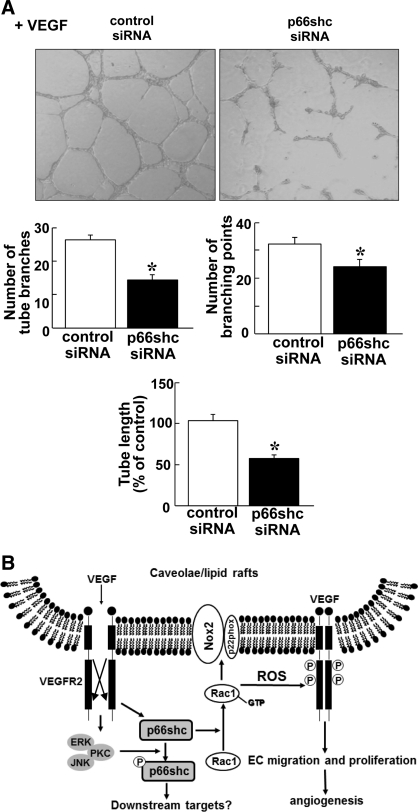

To determine the functional significance of p66Shc in VEGF signaling, we examined the role of p66Shc in VEGF-induced EC migration and proliferation. Wound scratch assay (Fig. 6A) and modified Boyden chamber assay (Fig. 6B) show that depletion of p66Shc with siRNA significantly inhibited VEGF-induced directional EC migration. We also found that VEGF-induced EC proliferation was also significantly inhibited by p66Shc siRNA (Fig. 6C). To determine the functional consequence of p66Shc-mediated EC migration and proliferation, we examined the role of p66Shc in VEGF-induced capillary network formation on Matrigel. Figure 7A shows that depletion of p66Shc significantly reduced the number of capillary tube branches, branching sprouts as well as tube length, suggesting that endogenous p66Shc plays an important role in VEGF-induced angiogenic responses in ECs.

Fig. 6.

p66Shc is involved in VEGF-induced cell migration in ECs. HUVECs transfected with control or p66Shc siRNAs were used for measurement of EC migration using modified Boyden chamber assay (A) or wound scratch assay (B) as well as EC proliferation (C). A: cell migration stimulated with VEGF for 6 h was measured using modified Boyden chamber method. Bar graph represents averaged data, expressed as cell number counted per 10 fields (x 200) and fold change over that in unstimulated cells (control). *P < 0.05. B: confluent monolayer of HUVECs were wound scratched in the presence of VEGF (20 ng/ml) to stimulate the EC migration toward the wound area. Images were captured immediately (0 h) and 24 h after the wound scratch. C: cells were cultured in 0.2% FBS containing medium with or without 20 ng/ml VEGF for 48 h and the cell number was measured. *P < 0.05, for the fold increase induced by VEGF vs. vehicle alone (n = 3).

Fig. 7.

Role of p66Shc in capillary-like network formation in ECs and proposed model. A: HUVECs were seeded on Matrigel-coated plates in culture media containing VEGF for 6 h. Eight random fields per well were imaged, and representative pictures are shown (top). Averaged numbers of capillary tube branches, branching points, and tube length per field are shown (bottom; n = 3). P < 0.05. B: proposed model for novel role of p66Shc in ROS-dependent VEGFR2 signaling and angiogenesis in ECs. VEGF stimulation promotes pS36-pp66Shc formation through ERK/JNK/PKC as well as association of nonphosphorylated form of p66Shc with Rac1, a component of Nox2 NADPH oxidase in ECs. p66Shc is involved in VEGF-induced Rac1 activation and ROS production, thereby promoting VEGFR2 activation in caveolae/lipid rafts, which in turn stimulates angiogenic responses in ECs.

DISCUSSION

Accumulating evidence reveals that p66Shc is a key regulator for various oxidative stress-dependent pathologies such as aging and cardiovascular diseases (3, 8, 10, 13, 26, 28, 29, 36). We (49) demonstrated that ROS derived from Rac1-dependent NADPH oxidase are involved in VEGFR2 autophosphorylation and angiogenic-related responses in ECs. However, a role of p66Shc in VEGF signaling and physiological responses in ECs is unknown. The present study demonstrates that VEGF stimulation increases pS36-p66Shc at least in part through ERK/JNK or PKC pathway as well as p66Shc association with Rac1, a component of NADPH oxidase in ECs. Moreover, depletion of p66Shc with siRNA blocks VEGF-induced Rac1 activation and ROS production, thereby inhibiting VEGFR2-pY in caveolae/lipid rafts as well as p38MAPK activation. Functionally, p66Shc siRNA inhibits VEGF-induced EC migration, proliferation, and capillary tube formation. These findings suggest that p66Shc functions as a positive regulator for ROS-dependent VEGFR2 signaling linked to angiogenesis in ECs (Fig. 7B).

p66Shc is shown to be phosphorylated at Ser36 by oxidative stress and insulin, EGF, endothelin-1 (5, 12, 20, 31), or angiotensin II (39) in various systems other than ECs. To our knowledge, the present study provides the first evidence that a key angiogenesis growth factor, VEGF, stimulates Ser36 phosphorylation of p66Shc. In response to stress factors, p66Shc is phosphorylated at Ser36 in N-terminal CH2 domain, which is not found in p46Shc and p52Shc, leading to H2O2 generation (14, 35). The upstream kinases responsible for pS36-p66Shc formation have been reported in other systems, including PKCβ (14), PKCδ (16), ERK (18), or JNK (1). Consistent with previous reports, we found that inhibitors for MEK, JNK, or PKC, but not for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase or p38MAPK, significantly reduce VEGF-induced pS36-p66Shc formation in ECs. Since Ser36 in p66Shc lies in the MAPK consensus phosphorylation motif, ERK or JNK may be the kinases that phosphorylate p66Shc. We confirmed that VEGF increases ERK and JNK phosphorylation within 5 min (unpublished observations). Thus our results suggest that VEGF increases pS36-p66Shc at least in part through ERK/JNK or PKC pathway in ECs. Detailed analysis of relationships among ERK, JNK, and PKC and identification of the subtypes of PKC involved in VEGF-induced pS36-p66Shc formation are the subjects of future studies.

We and others (48) reported that VEGF stimulation of ECs rapidly increases ROS by activation of Rac1-dependent NADPH oxidase. In this study, we show that VEGF stimulation rapidly promotes Rac1 association with nonphosphorylated form of p66Shc and that depletion of p66Shc with siRNA inhibits VEGF-induced Rac1 activation and ROS production. Given that Rac1 is a component of NADPH oxidase in ECs (2), these results suggest that p66Shc is at least involved in VEGF-induced ROS production via regulating Rac1-NADPH oxidase pathway. Consistent with our results, p66Shc is shown to mediate Rac1 activation through regulating a Rac-GEF (guanine nucleotide-exchange factor) such as son of sevenless 1 (Sos1; Ref. 22) or β-Pix (5). Tomilov et al. (43) recently demonstrate that O2− production by NADPH oxidase from macrophage is decreased in p66Shc−/− mice. Of note, S36-p66Shc phosphorylation has been shown to be involved in mitochondrial ROS production (8, 14, 26, 35), and most recent study (51) shows that VEGF stimulation increases mitochondrial ROS production in ECs. Thus one may speculate that p66Shc binding to Rac1 is required for VEGF-induced NADPH oxidase activation, while pS36-p66Shc is involved in mitochondrial ROS production in ECs. This point is currently under investigation.

Since ROS are highly diffusible molecules, localized ROS signal is important for efficient and specific activation of redox signaling events (6, 41, 47). VEGF-induced ROS are involved in activation of VEGFR2 (48), which occurs in part at caveolae/lipid rafts (19, 23, 32). In this study, we demonstrate that p66Shc siRNA significantly inhibits VEGF-induced increase in VEGFR2-pY in total lysates and caveolin-enriched lipid rafts where a fraction of Nox2 is found. Given that NADPH oxidase is activated in part at lipid rafts in ECs (25, 47, 53, 55), our result suggests that thep66Shc-mediated increase in ROS through NADPH oxidase promotes VEGFR2-pY in these specialized signaling domains. The mechanisms by which ROS mediate VEGFR2 phosphorylation remain unclear. Evidence suggests that reversible oxidative inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) by ROS is an important mechanism through which ROS increase tyrosine phosphorylation-mediated growth factor signaling (11, 37, 44). Consistent with this notion, we (32) previously demonstrated that extracellular H2O2 generated by extracellular superoxide dismutase localized at caveolae/lipid rafts facilitates an increase in VEGFR2-pY via oxidative inactivation of PTPs DEP-1/PTP1B. Furthermore, Guo et al. (16) reported that the α1-adrenergic receptor promotes p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation in caveolae via a ROS-dependent manner in cardiac myocytes. However, VEGF does not induce tyrosine phosphorylation of p66Shc in HUVECs (unpublished observations). These results suggest that VEGF-stimulated p66Shc/Rac1/ROS pathways may induce oxidative inactivation of PTPs localized at caveolae/lipid rafts, thereby promoting VEGFR2 activation.

We also examined the role of p66Shc in key VEGFR2 downstream signaling kinases involved in angiogenesis including p38MAPK and ERK1/2, which mainly mediate EC migration and proliferation, respectively. Knockdown of p66Shc significantly inhibits phosphorylation of p38MAPK but not ERK1/2, by VEGF. This in turn reduces VEGF-induced EC migration, proliferation, and capillary network formation, a key component of angiogenesis in ECs. Consistent with our data, a previous report (50) shows that p66Shc is involved in androgen-induced prostate cancer cell proliferation. The lack of p66Shc siRNA effect on VEGF-induced ERK activation suggests that other p66Shc downstream targets linked to EC proliferation than ERK1/2 may exist. Akt and/or forkhead related transcription factors FOXO3a/FKHRL1 (5, 16, 18, 30) or mammalian target of rapamycin-S6 kinase (33) will be additional possible targets of p66Shc in VEGF signaling.

Previous studies (3, 4, 8, 10, 14, 26, 28, 35, 36) using p66Shc knockout or knockdown approaches implicate a pathological role of p66Shc in mediating apoptosis and endothelial dysfunction involved in oxidative stress-associated aging and cardiovascular diseases. Indeed, p66Shc activation has been shown to induce oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction, while p66Shc inhibition exhibits vasoprotective effects (3, 13). By contrast, our findings suggest a physiological function of p66Shc in angiogenic signaling in ECs. Consistent with our data, Zaccagnini et al. (54) reported that p66Shc−/− mice subjected to ischemia/reperfusion show a more decreased capillary density in skeletal muscles than wild-type mice. Naldini et al. (27) showed that hypoxia-induced angiogenic response is impaired in p66Shc−/− T cells. Given that p66Shc−/− mice are not embryonic lethal, these results suggest that p66Shc is involved in postnatal angiogenesis in response to injury but not developmental angiogenesis. An opposite role of p66Shc may be due to the fact that intracellular ROS act as a double-edged sword depending on their concentration. In other words, a low concentration of ROS is required for biological responses such as cell migration, while excess an amount of ROS produced in pathological conditions induce apoptosis or cytotoxic effects. Both cases may be mediated through p66Shc. Thus, under the condition in which VEGF increases ROS that act as signaling molecules in VEGFR2 signaling, p66Shc functions as a positive regulator for angiogenic-related responses in ECs.

In summary, we demonstrate that VEGF stimulation promotes pS36-pp66Shc formation at least in part through the ERK/JNK or PKC pathway as well as association of a nonphosphorylated form of p66Shc with Rac1 in ECs. We also found that p66Shc is involved in VEGF-induced Rac1 activation and ROS production, thereby promoting VEGFR2 activation in caveolae/lipid rafts, which in turn stimulates angiogenic responses in ECs (Fig. 7B). These findings suggest that p66Shc is a key positive regulator of VEGF-induced ROS production and VEGFR2-mediated redox signaling linked to angiogenesis in ECs. Our study should provide insight into p66Shc as a potential therapeutic target for various angiogenesis-dependent diseases.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01-HL-077524 and HL-077524-S1 (to M. Ushio-Fukai) and HL-070187 (to T. Fukai), American Heart Association National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements Innovative Research Grant 0970336N (to M. Ushio-Fukai), and Uehara Memorial Foundation and Naito Foundation (to J. Oshikawa).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: J.O., S.-J.K., C.C., G.-F.C., T.F., and M.U.-F. conception and design of research; J.O., S.-J.K., E.F., C.C., G.-F.C., R.D.M., F.K., and I.L. performed experiments; J.O., S.-J.K., E.F., C.C., G.-F.C., R.D.M., F.K., and I.L. analyzed data; J.O., S.-J.K., C.C., G.-F.C., F.K., I.L., T.F., and M.U.-F. interpreted results of experiments; J.O., S.-J.K., E.F., G.-F.C., and M.U.-F. prepared figures; J.O. and M.U.-F. drafted manuscript; J.O., S.-J.K., G.-F.C., T.F., and M.U.-F. edited and revised manuscript; J.O., S.-J.K., E.F., C.C., G.-F.C., R.D.M., F.K., I.L., T.F., and M.U.-F. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Arany I, Faisal A, Nagamine Y, Safirstein RL. p66Shc inhibits pro-survival epidermal growth factor receptor/ERK signaling during severe oxidative stress in mouse renal proximal tubule cells. J Biol Chem 283: 6110–6117, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Babior BM. The NADPH oxidase of endothelial cells. IUBMB Life 50: 267–269, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Camici GG, Schiavoni M, Francia P, Bachschmid M, Martin-Padura I, Hersberger M, Tanner FC, Pelicci P, Volpe M, Anversa P, Luscher TF, Cosentino F. Genetic deletion of p66(Shc) adaptor protein prevents hyperglycemia-induced endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 5217–5222, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carpi A, Menabo R, Kaludercic N, Pelicci P, Di Lisa F, Giorgio M. The cardioprotective effects elicited by p66(Shc) ablation demonstrate the crucial role of mitochondrial ROS formation in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biochim Biophys Acta 1787: 774–780, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chahdi A, Sorokin A. Endothelin-1 couples betaPix to p66Shc: role of betaPix in cell proliferation through FOXO3a phosphorylation and p27kip1 down-regulation independently of Akt. Mol Biol Cell 19: 2609–2619, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen K, Craige SE, Keaney JF., Jr Downstream targets and intracellular compartmentalization in Nox signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 2467–2480, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Colavitti R, Pani G, Bedogni B, Anzevino R, Borrello S, Waltenberger J, Galeotti T. Reactive oxygen species as downstream mediators of angiogenic signaling by vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2/KDR. J Biol Chem 277: 3101–3108, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cosentino F, Francia P, Camici GG, Pelicci PG, Luscher TF, Volpe M. Final common molecular pathways of aging and cardiovascular disease: role of the p66Shc protein. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28: 622–628, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ebrahimian TG, Heymes C, You D, Blanc-Brude O, Mees B, Waeckel L, Duriez M, Vilar J, Brandes RP, Levy BI, Shah AM, Silvestre JS. NADPH oxidase-derived overproduction of reactive oxygen species impairs postischemic neovascularization in mice with type 1 diabetes. Am J Pathol 169: 719–728, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fadini GP, Ceolotto G, Pagnin E, de Kreutzenberg S, Avogaro A. At the crossroads of longevity and metabolism: the metabolic syndrome and life span determinant pathways. Aging Cell 10: 10–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Finkel T. Signal transduction by reactive oxygen species in non-phagocytic cells. J Leukoc Biol 65: 337–340, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Foschi M, Franchi F, Han J, La Villa G, Sorokin A. Endothelin-1 induces serine phosphorylation of the adaptor protein p66Shc and its association with 14–3-3 protein in glomerular mesangial cells. J Biol Chem 276: 26640–26647, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Francia P, delli Gatti C, Bachschmid M, Martin-Padura I, Savoia C, Migliaccio E, Pelicci PG, Schiavoni M, Luscher TF, Volpe M, Cosentino F. Deletion of p66shc gene protects against age-related endothelial dysfunction. Circulation 110: 2889–2895, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Giorgio M, Migliaccio E, Orsini F, Paolucci D, Moroni M, Contursi C, Pelliccia G, Luzi L, Minucci S, Marcaccio M, Pinton P, Rizzuto R, Bernardi P, Paolucci F, Pelicci PG. Electron transfer between cytochrome c and p66Shc generates reactive oxygen species that trigger mitochondrial apoptosis. Cell 122: 221–233, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Griendling KK, Sorescu D, Ushio-Fukai M. NAD(P)H oxidase: role in cardiovascular biology and disease. Circ Res 86: 494–501, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guo J, Gertsberg Z, Ozgen N, Steinberg SF. p66Shc links alpha1-adrenergic receptors to a reactive oxygen species-dependent AKT-FOXO3A phosphorylation pathway in cardiomyocytes. Circ Res 104: 660–669, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Haddad P, Dussault S, Groleau J, Turgeon J, Michaud SE, Menard C, Perez G, Maingrette F, Rivard A. Nox2-containing NADPH oxidase deficiency confers protection from hindlimb ischemia in conditions of increased oxidative stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 29: 1522–1528, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hu Y, Wang X, Zeng L, Cai DY, Sabapathy K, Goff SP, Firpo EJ, Li B. ERK phosphorylates p66shcA on Ser36 and subsequently regulates p27kip1 expression via the Akt-FOXO3a pathway: implication of p27kip1 in cell response to oxidative stress. Mol Biol Cell 16: 3705–3718, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ikeda S, Ushio-Fukai M, Zuo L, Tojo T, Dikalov S, Patrushev NA, Alexander RW. Novel role of ARF6 in vascular endothelial growth factor-induced signaling and angiogenesis. Circ Res 96: 467–475, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kao AW, Waters SB, Okada S, Pessin JE. Insulin stimulates the phosphorylation of the 66- and 52-kilodalton Shc isoforms by distinct pathways. Endocrinology 138: 2474–2480, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kaplan N, Urao N, Furuta E, Kim SJ, Razvi M, Nakamura Y, McKinney RD, Poole LB, Fukai T, Ushio-Fukai M. Localized cysteine sulfenic acid formation by vascular endothelial growth factor: role in endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis. Free Radic Res 45: 1124–1135, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Khanday FA, Santhanam L, Kasuno K, Yamamori T, Naqvi A, Dericco J, Bugayenko A, Mattagajasingh I, Disanza A, Scita G, Irani K. Sos-mediated activation of rac1 by p66shc. J Cell Biol 172: 817–822, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Labrecque L, Royal I, Surprenant DS, Patterson C, Gingras D, Beliveau R. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 activity by caveolin-1 and plasma membrane cholesterol. Mol Biol Cell 14: 334–347, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lamalice L, Houle F, Jourdan G, Huot J. Phosphorylation of tyrosine 1214 on VEGFR2 is required for VEGF-induced activation of Cdc42 upstream of SAPK2/p38. Oncogene 23: 434–445, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li PL, Gulbins E. Lipid rafts and redox signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal 9: 1411–1415, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Migliaccio E, Giorgio M, Mele S, Pelicci G, Reboldi P, Pandolfi PP, Lanfrancone L, Pelicci PG. The p66shc adaptor protein controls oxidative stress response and life span in mammals. Nature 402: 309–313, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Naldini A, Morena E, Pucci A, Pellegrini M, Baldari CT, Pelicci PG, Presta M, Ribatti D, Carraro F. The adaptor protein p66Shc is a positive regulator in the angiogenic response induced by hypoxic T cells. J Leukoc Biol 87: 365–369, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Napoli C, Martin-Padura I, de Nigris F, Giorgio M, Mansueto G, Somma P, Condorelli M, Sica G, De Rosa G, Pelicci P. Deletion of the p66Shc longevity gene reduces systemic and tissue oxidative stress, vascular cell apoptosis, and early atherogenesis in mice fed a high-fat diet. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 2112–2116, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nemoto S, Combs CA, French S, Ahn BH, Fergusson MM, Balaban RS, Finkel T. The mammalian longevity-associated gene product p66shc regulates mitochondrial metabolism. J Biol Chem 281: 10555–10560, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nemoto S, Finkel T. Redox regulation of forkhead proteins through a p66shc-dependent signaling pathway. Science 295: 2450–2452, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Okada S, Kao AW, Ceresa BP, Blaikie P, Margolis B, Pessin JE. The 66-kDa Shc isoform is a negative regulator of the epidermal growth factor-stimulated mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Biol Chem 272: 28042–28049, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Oshikawa J, Urao N, Kim HW, Kaplan N, Razvi M, McKinney R, Poole LB, Fukai T, Ushio-Fukai M. Extracellular SOD-derived H2O2 promotes VEGF signaling in caveolae/lipid rafts and postischemic angiogenesis in mice. PLos One 5: e10189, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pani G. P66SHC and ageing: ROS and TOR? Aging (Albany, NY) 2: 514–518, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pelicci G, Lanfrancone L, Grignani F, McGlade J, Cavallo F, Forni G, Nicoletti I, Grignani F, Pawson T, Pelicci PG. A novel transforming protein (SHC) with an SH2 domain is implicated in mitogenic signal transduction. Cell 70: 93–104, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pinton P, Rimessi A, Marchi S, Orsini F, Migliaccio E, Giorgio M, Contursi C, Minucci S, Mantovani F, Wieckowski MR, Del Sal G, Pelicci PG, Rizzuto R. Protein kinase C beta and prolyl isomerase 1 regulate mitochondrial effects of the life-span determinant p66Shc. Science 315: 659–663, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ranieri SC, Fusco S, Panieri E, Labate V, Mele M, Tesori V, Ferrara AM, Maulucci G, De Spirito M, Martorana GE, Galeotti T, Pani G. Mammalian life-span determinant p66shcA mediates obesity-induced insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 13420–13425, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rhee SG, Bae YS, Lee SR, Kwon J. Hydrogen peroxide: a key messenger that modulates protein phosphorylation through cysteine oxidation. Sci STKE 2000: PE1, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Song KS, Li S, Okamoto T, Quilliam LA, Sargiacomo M, Lisanti MP. Co-purification and direct interaction of Ras with caveolin, an integral membrane protein of caveolae microdomains. Detergent-free purification of caveolae microdomains. J Biol Chem 271: 9690–9697, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sun L, Xiao L, Nie J, Liu FY, Ling GH, Zhu XJ, Tang WB, Chen WC, Xia YC, Zhan M, Ma MM, Peng YM, Liu H, Liu YH, Kanwar YS. p66Shc mediates high-glucose and angiotensin II-induced oxidative stress renal tubular injury via mitochondrial-dependent apoptotic pathway. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F1014–F1025, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Takahashi T, Yamaguchi S, Chida K, Shibuya M. A single autophosphorylation site on KDR/Flk-1 is essential for VEGF-A-dependent activation of PLC-gamma and DNA synthesis in vascular endothelial cells. EMBO J 20: 2768–2778, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Terada LS. Specificity in reactive oxidant signaling: think globally, act locally. J Cell Biol 174: 615–623, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tojo T, Ushio-Fukai M, Yamaoka-Tojo M, Ikeda S, Patrushev NA, Alexander RW. Role of gp91phox (Nox2)-containing NAD(P)H oxidase in angiogenesis in response to hindlimb ischemia. Circulation 111: 2347–2355, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tomilov AA, Bicocca V, Schoenfeld RA, Giorgio M, Migliaccio E, Ramsey JJ, Hagopian K, Pelicci PG, Cortopassi GA. Decreased superoxide production in macrophages of long-lived p66Shc knock-out mice. J Biol Chem 285: 1153–1165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tonks NK. Redox redux: revisiting PTPs and the control of cell signaling. Cell 121: 667–670, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Urao N, Inomata H, Razvi M, Kim HW, Wary K, McKinney R, Fukai T, Ushio-Fukai M. Role of nox2-based NADPH oxidase in bone marrow and progenitor cell function involved in neovascularization induced by hindlimb ischemia. Circ Res 103: 212–220, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ushio-Fukai M. Compartmentalization of redox signaling through NADPH oxidase-derived ROS. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 1289–1299, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ushio-Fukai M. Localizing NADPH oxidase-derived ROS. Sci STKE 2006: re8, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ushio-Fukai M. VEGF signaling through NADPH oxidase-derived ROS. Antioxid Redox Signal 9: 731–739, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ushio-Fukai M, Tang Y, Fukai T, Dikalov SI, Ma Y, Fujimoto M, Quinn MT, Pagano PJ, Johnson C, Alexander RW. Novel role of gp91(phox)-containing NAD(P)H oxidase in vascular endothelial growth factor-induced signaling and angiogenesis. Circ Res 91: 1160–1167, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Veeramani S, Yuan TC, Lin FF, Lin MF. Mitochondrial redox signaling by p66Shc is involved in regulating androgenic growth stimulation of human prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 27: 5057–5068, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang Y, Zang QS, Liu Z, Wu Q, Maass D, Dulan G, Shaul PW, Melito L, Frantz DE, Kilgore JA, Williams NS, Terada LS, Nwariaku FE. Regulation of VEGF induced endothelial cell migration by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 301: C695–C704, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yamaoka-Tojo M, Ushio-Fukai M, Hilenski L, Dikalov SI, Chen YE, Tojo T, Fukai T, Fujimoto M, Patrushev NA, Wang N, Kontos CD, Bloom GS, Alexander RW. IQGAP1, a novel vascular endothelial growth factor receptor binding protein, is involved in reactive oxygen species-dependent endothelial migration and proliferation. Circ Res 95: 276–283, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yang B, Oo TN, Rizzo V. Lipid rafts mediate H2O2 prosurvival effects in cultured endothelial cells. FASEB J 20: 1501–1503, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zaccagnini G, Martelli F, Fasanaro P, Magenta A, Gaetano C, Di Carlo A, Biglioli P, Giorgio M, Martin-Padura I, Pelicci PG, Capogrossi MC. p66ShcA modulates tissue response to hindlimb ischemia. Circulation 109: 2917–2923, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhang AY, Yi F, Zhang G, Gulbins E, Li PL. Lipid raft clustering and redox signaling platform formation in coronary arterial endothelial cells. Hypertension 47: 74–80, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]