Abstract

Chronic hypertension induces cardiac remodeling, including left ventricular hypertrophy and fibrosis, through a combination of both hemodynamic and humoral factors. In previous studies, we showed that the heptapeptide ANG-(1–7) prevented mitogen-stimulated growth of cardiac myocytes in vitro, through a reduction in the activity of the MAPKs ERK1 and ERK2. In this study, saline- or ANG II-infused rats were treated with ANG-(1–7) to determine whether the heptapeptide reduces myocyte hypertrophy in vivo and to identify the signaling pathways involved in the process. ANG II infusion into normotensive rats elevated systolic blood pressure >50 mmHg, in association with increased myocyte cross-sectional area, ventricular atrial natriuretic peptide mRNA, and ventricular brain natriuretric peptide mRNA. Although infusion with ANG-(1–7) had no effect on the ANG II-stimulated elevation in blood pressure, the heptapeptide hormone significantly reduced the ANG II-mediated increase in myocyte cross-sectional area, interstitial fibrosis, and natriuretic peptide mRNAs. ANG II increased phospho-ERK1 and phospho-ERK2, whereas cotreatment with ANG-(1–7) reduced the phosphorylation of both MAPKs. Neither ANG II nor ANG-(1–7) altered the ERK1/2 MAPK kinase MEK1/2. However, ANG-(1–7) infusion, with or without ANG II, increased the MAPK phosphatase dual-specificity phosphatase (DUSP)-1; in contrast, treatment with ANG II had no effect on DUSP-1, suggesting that ANG-(1–7) upregulates DUSP-1 to reduce ANG II-stimulated ERK activation. These results indicate that ANG-(1–7) attenuates cardiac remodeling associated with a chronic elevation in blood pressure and upregulation of a MAPK phosphatase and may be cardioprotective in patients with hypertension.

Keywords: cardiac hypertrophy, mitogen-activated protein kinases

the renin-angiotensin system plays a critical role in the regulation of blood pressure. ANG II is a potent vasoconstrictor, stimulates thirst, and increases aldosterone release, and inhibition of its production or effect with the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or ANG II receptor (ANG II type 1 receptor) antagonists reduces mean arterial pressure (11). In addition to these systemic actions, ANG II exerts direct trophic actions within the heart, stimulating both cardiac myocyte hypertrophy and fibroblast proliferation and contributing to pathological cardiac remodeling in hypertension.

ANG-(1–7) is an endogenous peptide hormone that produces unique physiological responses that are often opposite to the effects of ANG II. In addition to participating in the antihypertensive responses to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition or ANG II type 1 receptor blockade (25, 26), the heptapeptide reduces vascular growth in vitro and in vivo (14, 39, 42). ANG-(1–7) has been identified in the venous effluent from the canine coronary sinus (37) and was produced from ANG I and ANG II in the interstitial fluid collected from microdialysis probes placed in canine left ventricles (LVs) (44), demonstrating that the heptapeptide hormone can be generated directly in the heart. Intense ANG-(1–7) immunoreactivity was identified in rat hearts after coronary artery occlusion, primarily in association with myocytes and in regions surrounding the ischemic zone, suggesting a role for the heptapeptide in cardiac remodeling (2). Subsequent studies have revealed a cardioprotective role for ANG-(1–7), as the heptapeptide reduced the incidence and duration of reperfusion arrhythmias (12, 13), improved postischemic cardiac function of transgenic rats with elevated ANG-(1–7) due to expression of an ANG-(1–7)-producing fusion protein (38), and activated cardiac Na+-ATPase to hyperpolarize heart cells and reestablish impulse conduction after ischemia-reperfusion (8). These studies suggest that ANG-(1–7) plays a role in the regulation of cardiac function.

ANG-(1–7) also reduced the growth of cardiomyocytes. Loot and colleagues (28) demonstrated that an 8-wk infusion of ANG-(1–7) after coronary artery ligation prevented the deterioration of cardiac function with an associated decrease in myocyte cross-sectional area (CSA). The heptapeptide attenuated cardiac hypertrophy after ANG II infusion into normotensive rats, in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats, spontaneously hypertensive rats, or fructose-fed rats or in transgenic mice containing an ANG-(1–7)-fusion protein (18, 20, 21, 30, 33, 36). Previous findings from our laboratory have demonstrated that cultured cardiac myocytes contain the ANG-(1–7) Mas receptor, which mediates the heptapeptide-induced reduction in mitogen-stimulated leucine incorporation into newly synthesized protein. The decrease in myocyte protein synthesis was associated with an ANG-(1–7)-mediated reduction in the activity of the MAPKs ERK1 and ERK2, and these effects were blocked by either an ANG-(1–7) receptor antagonist or antisense oligonucleotides to the Mas receptor (43). In the present study, normotensive Sprague-Dawley rats were infused with ANG II to induce cardiac remodeling and coinfused with ANG-(1–7) to identify the molecular mechanism for the ANG-(1–7)-mediated reduction in cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 270–300 g were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Raleigh, NC). All animals were housed in standard shoebox cages and maintained on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle with free access to standard rat chow and water. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Wake Forest University.

Materials.

ANG II and ANG-(1–7) were obtained from Bachem California (Torrance, CA). Phospho-specific antibodies against ERK1/2 and antibodies against MEK1/2 and ERK2 were obtained from Cell Signaling (Cambridge, MA); an antibody against dual-specificity phosphatase [DUSP-1; also called MAPK phosphatase (MKP)-1] was obtained from Upstate (Lake Placid, NY). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated.

ANG II infusion model.

Hypertension and cardiac remodeling were induced by a chronic subcutaneous infusion of ANG II (24 μg·kg−1·h−1 or 400 ng·kg−1·min−1) delivered for 4 wk by osmotic minipump (model 2ML4, Alzet, Cupertino, CA). Pumps were implanted subcutaneously on the back of the rats between the shoulder blades while animals were anesthetized with 3% isofluorane. Osmotic minipumps contained either 0.9% saline, ANG II (24 μg·kg−1·h−1), ANG-(1–7) (24 μg·kg−1·h−1), or a combination of ANG-(1–7) and ANG II (both at a concentration of 24 μg·kg−1·h−1). Animals were allowed to recover for 2 days before blood pressure was measured. Each treatment group included six rats, and no rodents died during the experimental treatment.

Indirect blood pressure.

Indirect blood pressure was recorded weekly by tail-cuff plesthymography. Each rat was warmed by a 200-W heating lamp for 5 min before restraint in a heated metal box to which the animal was previously conditioned during a period of 3–5 days. A sensor assembly with a photodiode and integrated circuit was used to detect blood flow through the tail. The light-emitting diode (LED) assembly contained a bright red LED for illuminating the tail to detect blood pulse. The specimen platform electronics incorporated a 12-bit analog-to-digital converter with a signal resolution of ±2,048 values for each sample (model SC100, Hatteras Instruments, Cary, NC). At least three to five separate measurements of blood pressure were averaged from each animal on the day of the recording. All pressures were recorded at the same time of day by the same individual.

Cardiac remodeling.

Hearts were removed by blunt dissection; the atria were separated from the ventricles and discarded, and the heart ventricles [including both the LV and right ventricle (RV) as well as the interventricular septum] were weighed. A section of LV tissue from each rat was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA and protein isolation; an adjacent cross section (including both the LV and RV as well as the interventricular septum) was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin for cell morphology or with collagen-specific picrosirius red (Direct Red 80, Sigma Chemical) for the detection of fibrosis. Myocyte CSA was determined at a magnification of ×400 using Simple PCI software. Quantification of myocyte CSA was carried out by two individuals who were blinded to the treatments. Each observer traced the borders of ∼20 cardiac myocytes in 5–6 separate images from different (nonoverlapping) regions of the LV free wall. The results from each animal were averaged for statistical analysis. The percentage of interstitial fibrosis in the LV was determined by morphometry of picrosirius red-stained sections at a magnification of ×200 using Photoshop 7.0 image analysis. The percentage of the collagen fraction was calculated as the sum of picrosirius red-stained connective tissue (excluding perivascular collagen areas) in the entire section divided by the total connective tissue and muscle area, expressed as a percentage. All samples were analyzed by two individuals who were blinded to the treatments. Each observer examined a minimum of five separate images from different (nonoverlapping) regions of the LV free wall. The results for each animal were averaged for statistical analysis.

Immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 5-μm-thick sections of the LV of each rat using polyclonal antibodies against phospho-ERK1/2 (1:75 dilution, Cell Signaling Technologies, Cambridge, MA) or DUSP1 (MKP-1; 1:400 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). The antibodies were used independently to detect immunoreactivity by an alkaline phosphatase method, with a biotinylated anti-rabbit secondary antibody as the linking reagent and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (BioGenex, San Ramon, CA) for labeling. The Vector Red chromogen (Vector, Burlingame, CA) was diluted in 50 mmol/l Tris·HCl (pH 8.2) and applied to slides for 5 min. Negative controls included sections incubated with nonimmune serum rather than the primary antibody. Photomicrographs of the resultant immunoreactive staining were obtained with light microscopy using a Leica DM 4000 microscope (Leica Microsystems, Bannockburn, IL) and photographed with a QImaging Retiga 1300R camera (QImaging, Surey, BC, Canada). Selected sections were photographed without the knowledge of treatment group at a magnification of ×400 in a 0.3-mm2 field using Simple PCI (version 6.0) computer-assisted imaging software.

RNA isolation and real-time RT-PCR.

RNA was isolated from the LV of each rat heart using TRIzol reagent (GIBCO Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as directed by the manufacturer. The RNA was incubated with RQ1 DNase (Promega, Madison, WI) to eliminate any residual DNA that would amplify during PCR. RNA concentration and integrity were assessed with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer with an RNA 6000 Nano LabChip (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). Approximately 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed using avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing deoxyribonucleotides, random hexamers, and RNase inhibitor in the RT buffer. The RT reaction product was heated at 95°C to terminate the reaction. For real-time PCR, 2 μl of the resultant cDNA were added to TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP)-specific, brain natriuretic peptide (BNP)-specific, MEK1/2-specific, and DUSP-1 (MKP-1)-specific primer/probe sets, and amplification was performed on the ABI 7000 Sequence Detection System. The mixtures were heated at 50°C for 2 min and at 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. All reactions were performed in triplicate, and 18S rRNA, amplified using the TaqMan rRNA control kit (Applied Biosystems), served as an internal control. The results were quantified as Ct values, where Ct is defined as the threshold cycle of PCR at which the amplified product is first detected, and the values were expressed as the ratio of the target to control using the 2−ΔΔCt method, as described by Applied Biosystems (User Bulletin No. 2 online).

Western blot hybridization.

Tissue from the LV (1–2 mm2 in size) was sonicated in Triton X-100 lysis buffer with protease inhibitors [100 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, and 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.4) containing 0.01 mM NaVO4, 0.1 mM PMSF, and 0.6 μM leupeptin]. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 5 min. Protein concentration was measured by a modification of the Lowry method (29). Solubilized proteins (25 μg/well) from saline-, ANG II-, ANG-(1–7)-, and ANG II + ANG-(1–7)-treated animals were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinyl membranes (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ). Nonspecific binding was blocked by 5% Blotto (5% dry milk and 0.1% Triton X-100) in Tris-buffered saline [50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.4) and 50 mM NaCl]. Membranes were incubated with a phospho-ERK1/2 antibody (1:1,000), a MEK1/2 antibody (1:1,000), or a DUSP-1 (MKP-1) antibody (1:1,000) followed by a goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:1,000, Amersham Pharmacia) coupled to horseradish peroxidase. Chemiluminescence reagents were added to visualize the immunoreactive bands, which were quantified by densitometry. An antibody to β-actin (Sigma Chemical) or ERK2 served as the loading control.

Statistics.

All data are presented as means ± SE. Statistical differences were evaluated by ANOVA followed by Dunnett's or Bonferroni's post hoc test. The criterion for statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Reduction in ANG II-induced cardiac remodeling by treatment with ANG-(1–7).

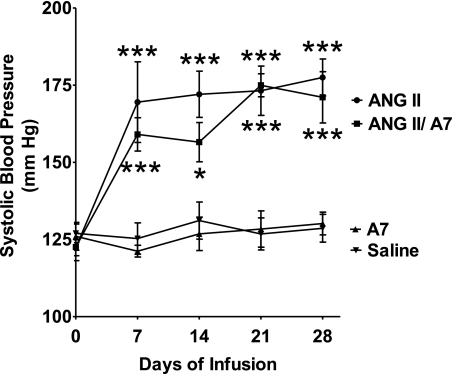

Rats were treated with saline or ANG II (24 μg·kg−1·h−1) for 28 days using a subcutaneously implanted osmotic minipump to increase blood pressure and induce cardiac myocyte remodeling. An additional group of rats was coinfused with ANG II and a similar dose of ANG-(1–7) to determine the effect of the heptapeptide on the changes mediated by ANG II. A fourth group of rats was treated with ANG-(1–7) alone, at the same dose, to determine direct effects of the heptapeptide. There were no differences in systolic blood pressures between the four groups of rats before the initiation of treatment. Chronic infusion of ANG II caused a significant increase in systolic blood pressure, which was not changed by the coinfusion of ANG-(1–7), as shown in Fig. 1. The marked increase in systolic blood pressure by ANG II infusion, in the presence or absence of ANG-(1–7), was observed 1 wk after the initiation of the study and remained elevated throughout the study. Infusion of ANG-(1–7) alone had no effect on systolic blood pressure compared with saline-infused animals.

Fig. 1.

Effects of ANG peptides on systolic blood pressure. Tail-cuff blood pressure was determined weekly in rats treated with saline, ANG II, ANG-(1–7) (A7), or a combination of ANG II and A7, as shown. Values are means ± SE; n = 6. *P < 0.05 compared with saline treatment; ***P < 0.001 compared with saline treatment.

The LV and RV were weighed; heart wet weight was recorded and normalized to body mass to determine the presence of cardiac hypertrophy. Initial body weights were not different between the four treatment groups and averaged 275 ± 7.3 g (n = 24). After treatment, body weight was increased in all four groups compared with their initial weight but tended to be lower in rats treated with ANG II, as shown in Table 1; however, the differences were not statistically different with any of the treatments (P = 0.07). Additionally, ventricular weights were similar among all groups. In animals infused with ANG II, the calculated heart weight-to-body weight ratio was significantly higher than in saline-infused controls, and a similar effect was observed in animals coinfused with ANG II and ANG-(1–7), as shown in Table 1. However, the calculated heart weight-to-body weight ratio in animals infused with ANG-(1–7) alone was not different from control animals. These data show that ANG II infusion increased the heart weight-to-body weight ratio, mainly due to the decrease in body weight. Coinfusion with ANG-(1–7) did not prevent this increase in the ratio, nor did the heptapeptide hormone alter the trend for lower body weight.

Table 1.

General characteristics after ANG peptide treatment

| Treatment | Body Weight, g | Ventricle Weight, mg | Ventricle Weight/Body Weight, mg/g |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saline | 418.3 ± 18.1 | 1201 ± 66 | 3.04 ± 0.19 |

| ANG II | 357.3 ± 28.0 | 1290 ± 84 | 3.64 ± 0.13* |

| ANG II/ANG-(1–7) | 374.3 ± 17.6 | 1359 ± 54 | 3.65 ± 0.15* |

| ANG-(1–7) | 421.4 ± 9.3 | 1097 ± 29 | 2.61 ± 0.06 |

Values are means ± SE; n = 6 animals/group.

P < 0.05 compared with saline treatment.

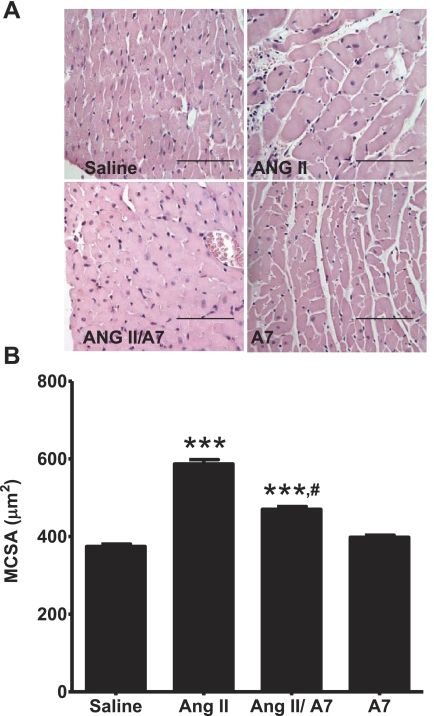

Cross sections of LVs were examined at a magnification of ×400 to assess mean CSA (MCSA). Infusion with ANG II increased the average myocyte MCSA by 57.2% compared with myocytes from saline-treated animals (P < 0.001). Coinfusion with ANG-(1–7) significantly attenuated the ANG II-mediated increase in MCSA, to 25.5% of the saline control (P < 0.001), as shown in Fig. 2. In contrast, the MCSA of myocytes from the LV of rats infused with ANG-(1–7) alone was not different than those infused with saline.

Fig. 2.

Effect of ANG peptides on myocyte mean cross-sectional area (MCSA). A: hemotoxylin-eosin-stained sections were used to evaluate myocyte MCSA in rats treated with saline, ANG II, A7, or a combination of ANG II and A7, as shown. Magnification: ×400. Bars = 100 μm. B: MCSA was determined using the Simple PCI program in 6 rats/group (100–140 myocytes/rat). ***P < 0.001 compared with rats infused with saline; #P < 0.001, rats treated with combined ANG II and A7 treatment compared with rats treated with ANG II alone.

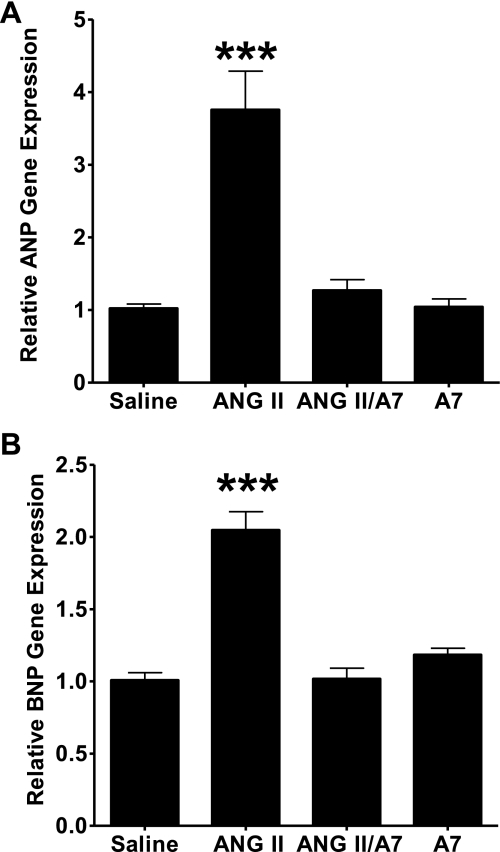

ANP and BNP mRNAs, as markers of LV hypertrophy, were quantified by real-time RT-PCR to further demonstrate the role of ANG peptides in cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling. Infusion of ANG II markedly increased ANP relative gene expression compared with hearts of animals infused with saline, as shown in Fig. 3A. Cardiac BNP mRNA was similarly increased by the infusion with ANG II, as shown in Fig. 3B. Concomitant treatment with ANG-(1–7) significantly attenuated the increase in both ANP and BNP mRNA compared with infusion with ANG II alone. Treatment with ANG-(1–7) alone had no significant effect on relative ANP or BNP mRNA in vivo compared with expression in rats infused with saline.

Fig. 3.

ANG peptides alter atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) in rat hearts. Total RNA was isolated from the left ventricles of rats treated with saline, ANG II, A7, or a combination of ANG II and A7, as shown, and subjected to real-time RT-PCR for ANP (A) and BNP (B). Amplification curves were normalized to 18S rRNA. All signals are relative to control, which was set to 1. Results are means ± SE; n = 6. ***P < 0.001 compared with hearts of rats treated with saline.

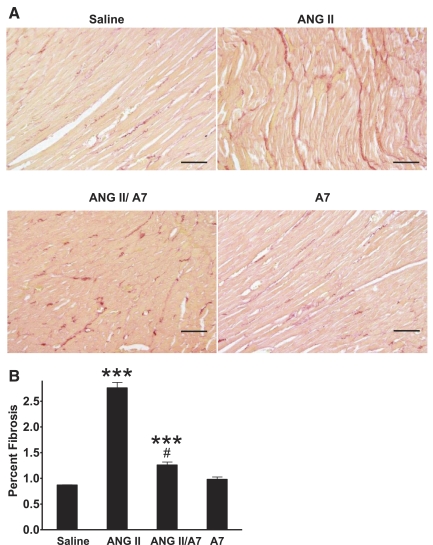

ANG-(1–7) reduces ANG II-mediated cardiac fibrosis.

Picrosirius red-stained LV cross sections were examined at a magnification of ×200 to assess cardiac fibrosis. As shown in Fig. 4, chronic infusion of ANG II caused a marked increase in interstitial fibrosis compared with saline-infused animals. The increase in interstitial fibrosis with ANG II infusion was significantly attenuated by the coadministration of ANG-(1–7). The degree of interstitial fibrosis in the group treated with ANG-(1–7) alone was not different from the saline-infused group. These results demonstrate that ANG-(1–7) attenuates the increase in interstitial fibrosis in response to ANG II and suggests that treatment with the heptapeptide reduced collagen deposition.

Fig. 4.

Effect of ANG peptides on ventricular interstitial fibrosis. Interstitial fibrosis was assessed in picrosirius red-stained sections from rats infused with saline, ANG II, A7, or a combination of ANG II and A7. A: representative images of interstitial fibrosis. Magnification: ×200. Bars = 100 μm. B: quantified data. Values are means ± SE from all animals; n = 6. ***P < 0.001 compared with saline treatment; #P < 0.001 compared with ANG II treatment.

ANG-(1–7) upregulates DUSP-1 in association with a decrease in ANG II-mediated phosphorylation of ERK1/2.

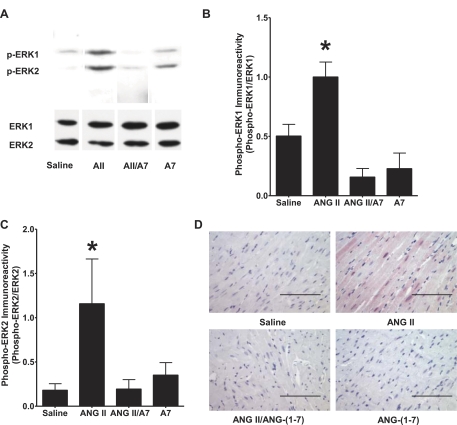

Activation of MAPK ERK1/2, through agonist-mediated stimulation of MEK1/2, is a major signaling pathway induced by ANG II to regulate gene transcription in cardiac myocytes (1, 34). Treatment of rats with ANG II significantly increased the phosphorylation of ERK1 and ERK2 in the LV compared with saline-infused animals, as shown in Fig. 5, A–C. In contrast, the coadministration of ANG-(1–7) and ANG II resulted in a marked decrease in ERK1/2 phosphorylation compared with ANG II alone. Cardiac phospho-ERK1/2 in rats infused with ANG-(1–7) alone was not different from saline-infused animals. Phospho-ERK1/2 immunoreactivity was also visualized in LV myocytes of rats treated with ANG II, ANG-(1–7), or both peptide hormones. As shown in Fig. 5D, significant immunoreactivity was observed in the myocytes of hearts from ANG II-treated rats, whereas minimal immunoreactivity was found in myocytes from sham rats, rats treated with ANG-(1–7), or rats administered both ANG II and ANG-(1–7), in agreement with the results of Western blot hybridization.

Fig. 5.

Effect of ANG peptides on ERK1/2 MAPK activity in rat hearts. Phosphorylated (p-)ERK1 and p-ERK2 were measured in homogenates of the rat left ventricle by Western blot hybridization or by immunohistochemistry using phospho-specific ERK1/2 antibodies. A: representative Western blots. B: p-ERK1 immunoreactivity. C: p-ERK2 immunoreactivity. Unphosphorylated ERK1 or ERK2 was used as a loading control. Data are presented as p-ERK1 or p-ERK2 relative immunoreactivity to total ERK1 or ERK2, respectively. n = 4. *P < 0.05 compared with protein isolated from the left ventricles of rats treated with saline. D: representative images of the left ventricles of rats treated with saline, ANG II, A7, or a combination of ANG II and A7 stained with an antibody to p-ERK1/2. Magnification: ×400. Bars = 100 μm.

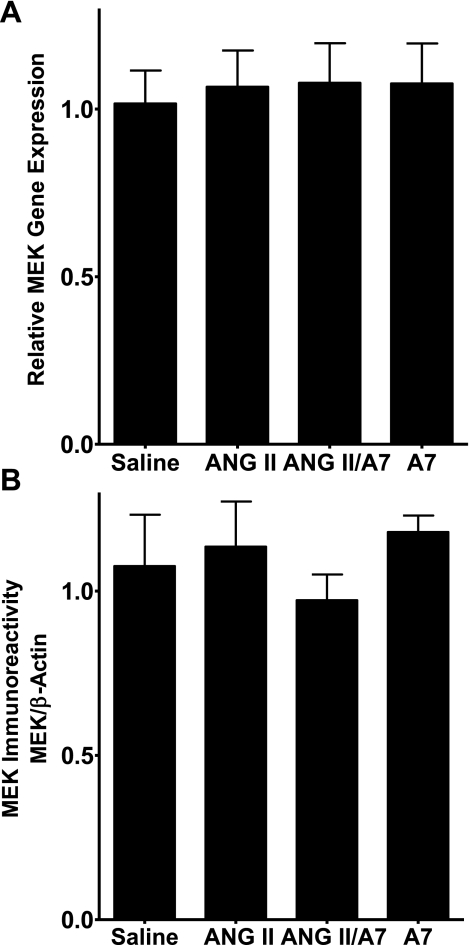

ERK1 and ERK2 are phosphorylated and activated by the MAPK kinases MEK1 and MEK2. Total MEK1/2 mRNA and protein in the LVs of rats infused with saline or ANG peptides were measured by real-time RT-PCR and Western blot hybridization, respectively, to determine whether the reduction in ERK1/2 activity was due to a decrease in MEK. None of the treatments significantly altered the relative gene expression of MEK1/2, as shown in Fig. 6A. Similarly, neither ANG II nor ANG-(1–7) administration altered the amount of immunoreactive MEK1/2, as shown in Fig. 6B.

Fig. 6.

ANG peptides do not alter MEK1/2 gene or protein expression in the rat heart. A: total RNA was isolated from the left ventricles of rats treated with saline, ANG II, A7, or a combination of ANG II and A7, as shown, and MEK1/2 mRNA was measured by real-time RT-PCR. Amplification curves were normalized to 18S rRNA. All signals are relative to control, which was set to 1. B: protein was isolated from the left ventricles of rats treated with saline, ANG II, A7, or a combination of ANG II and A7, as shown, and MEK1/2 protein was measured by Western blot hybridization using a specific MEK1/2 antibody. The relative density of each protein sample was compared with the density of β-actin, which was used as a loading control. Results are means ± SE; n = 6.

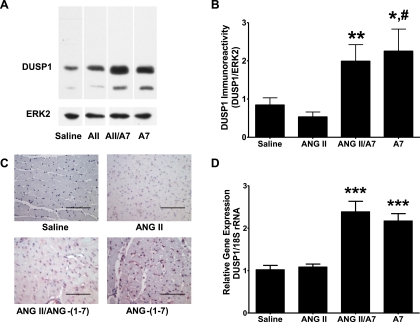

Since ERK1 and ERK2 are activated by phosphorylation on both tyrosine and threonine residues, their activities are inactivated by dephosphorylation by protein phosphatases, either a tyrosine-specific phosphatase and a serine/threonine-specific phosphatase or one of the family of DUSPs (32). DUSP-1, also known as MKP-1, is expressed in the heart, where the enzyme inactivates ERK1 and ERK2 (5). DUSP-1 in the LVs of rats treated with saline or ANG peptides was quantified by Western blot hybridization to determine whether ANG-(1–7) upregulates DUSP-1 to reduce ERK1/2 activity. Treatment of rats with ANG-(1–7) significantly increased DUSP-1 immunoreactivity in the heart compared with animals treated with saline, as shown in Fig. 7, A and B. A similar increase in DUSP-1 immunoreactivity was observed in rats coinfused with ANG II and ANG-(1–7) compared with ANG II alone; the DUSP-1 concentration in the hearts from ANG II-infused rats was not statistically different from the levels found in cardiac tissue from saline-infused control animals. Since phospho-ERK1 and phospho-ERK2 are substrates for DUSP-1, the ANG-(1–7)-mediated reduction in immunoreactive phospho-ERK1/2, as shown in Fig. 4, is an assessment of increased phosphatase activity after ANG-(1–7) treatment. DUSP-1 immunoreactivity was also increased within the nucleus of striated muscle cells in the hearts of rats administered ANG-(1–7), in the presence or absence of ANG II, as shown in Fig. 7C. In contrast, little immunoreactive product was visible in the hearts of rats treated with saline or ANG II alone, in agreement with the quantitative results of Western blot hybridization. DUSP-1 mRNA was quantified in homogenates from the ventricles of rats treated with saline or ANG peptides by real-time RT-PCR. DUSP-1 mRNA was significantly increased in the ventricles of rats treated with ANG-(1–7), in the presence or absence of ANG II, compared with saline-treated rats (P < 0.001), as shown in Fig. 7D; in contrast, there were no differences in DUSP-1 in the ventricles from rats treated with ANG II compared with saline-treated rats.

Fig. 7.

A7 upregulates dual-specifity phosphatase (DUSP)-1 in rat hearts. DUSP-1 protein was analyzed by Western blot hybridization and immunohistochemistry using antibodies specific for DUSP-1, and DUSP-1 mRNA was analyzed by real-time RT-PCR in the left ventricles of rats treated with saline, ANG II (AII), A7, or a combination of ANG II and A7. A: representative Western blots. The ∼40-kDa immunoreactive band was quantified as DUSP-1; the lower molecular weight band may represent a degradation production of DUSP-1 but was not used in the quantification. B: quantitative DUSP-1 immunoreactivity of the Western blot hybridization. Total ERK2 antibody was used as a loading control. Data are presented as DUSP-1 relative density to total ERK2 relative density. n = 4. *P < 0.05 compared with protein isolated from the left ventricles of rats treated with saline; **P < 0.05 compared with protein isolated from the left ventricles of rats treated with ANG II; #P < 0.01 compared with protein isolated from the left ventricles of rats treated with ANG II. C: representative images of sections from the left ventricles of rats treated with saline, ANG II, A7, or a combination of ANG II and A7 stained with an antibody to DUSP-1. Magnification: × 400. Bars = 100 μm. D: DUSP-1 mRNA was analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. Data are presented as relative gene expression. n = 6. ***P < 0.001 compared with mRNA isolated from the left ventricles of rats treated with saline.

DISCUSSION

A 4-wk infusion of ANG II into normotensive Sprague-Dawley rats elevated blood pressure and caused cardiac myocyte hypertrophy, as demonstrated by a significant increase in the MCSA of cardiomyocytes and an upregulation of the mRNA for the hypertrophic markers ANP and BNP. In contrast, coinfusion with the heptapeptide ANG-(1–7) significantly reduced the ANG II-induced increase in myocyte size and prevented the increase in natriuretic peptide mRNA levels. These results suggest that ANG-(1–7) inhibits the stimulated growth of cardiac myocytes in vivo, in agreement with previous studies showing that the heptapeptide reduced the serum-stimulated growth of cultured neonatal cardiac myocytes (43) and decreased myocyte CSA in the LV of rats treated with the heptapeptide for 8 wk after coronary artery ligation (28). Although ANG-(1–7) reduced the ANG II-mediated increase in MCSA and fibrosis, the increase in ventricular weight by ANG II was not decreased by the coadministration of ANG-(1–7). This difference may reflect a lack of effect of ANG-(1–7) on the increase in salt and water retention by ANG II, which would elevate the interstitial fluid in the heart. Additionally, there was no effect of ANG-(1–7) infusion on the ANG II-mediated increase in the heart weight-to-body weight ratio; however, the trend for a lower body weight in ANG II-infused animals, often observed in this model of hypertension (6, 10), may obscure a reduction in the heart weight-to-body weight ratio by ANG-(1–7) coinfusion. The observed decrease in cardiac myocyte CSA by coinfusion with ANG-(1–7) and ANG II, along with a reduction in the markers of cardiac hypertrophy (ANP and BNP), demonstrates that ANG-(1–7) reduces cardiac myocyte hypertrophy in vivo.

ANG II increased blood pressure by >50 mmHg after 4 wk of peptide infusion, whereas infusion with ANG-(1–7) alone had no effect on blood pressure. Furthermore, coadministration of ANG-(1–7) with ANG II did not reduce the ANG II-induced increase in blood pressure. This suggests that the ANG-(1–7)-mediated attenuation of cardiac hypertrophy results from a humoral, rather than a hemodynamic, etiology. Previous studies have shown that infusion of ANG II significantly increases systolic blood pressure (20, 30), whereas coinfusion of ANG-(1–7) with ANG II did not alter the increase in blood pressure in normotensive rat strains (3, 20). This demonstrates that the reduction in cardiac hypertrophy observed in Sprague-Dawley rats coinfused with ANG II and ANG-(1–7) was pressure independent and was due to direct effects of the heptapeptide on the myocardium.

ANG II treatment increased the expression of the hypertrophic markers ANP and BNP in association with an increase in myocyte CSA. In contrast, infusion of ANG-(1–7) significantly reduced myocyte CSA and both ANP and BNP in rats coinfused with ANG II. The reduction in cardiac myocyte size correlates with previous studies showing that ANG-(1–7) administration reduces cardiac myocyte cell growth in vivo (20, 21, 28) and in vitro (43). In addition to serving as a marker of cardiac hypertrophy, ANP may act as a negative regulator of LV hypertrophy, since it is an early response gene upregulated in the hypertrophied heart and inhibits the growth of cardiac myocytes (23). Conditioned media from ANG II-stimulated cardiac fibroblasts significantly induced ANP gene expression in cardiac myocytes in vitro; however, pretreatment of cardiac fibroblasts with ANG-(1–7) significantly attenuated the ANG II-stimulated hypertrophic response (24). Collectively, these studies support the hypothesis that ANG-(1–7) protects the heart from cardiac myocyte hypertrophy and reduces both ANP and BNP.

Cardiac fibrosis is a major component of hypertensive heart disease and interferes with the normal function and structure of the myocardium. In the model of ANG II-dependent hypertension used in the present study, we observed substantial increases in interstitial fibrosis with chronic ANG II infusion. In contrast, coinfusion with ANG-(1–7) significantly attenuated collagen deposition in the interstitial space, suggesting that the heptapeptide hormone reduces the ANG II-induced increase in cardiac remodeling by attenuating the activity of cardiac fibroblasts. This is in agreement with previous studies (20, 30) showing that systemic infusion of ANG-(1–7) or direct delivery of ANG-(1–7) into the heart using an ANG-(1–7)-fusion protein reduced interstitial fibrosis in various models of hypertension. Collectively, these results demonstrate that ANG-(1–7) inhibits fibrosis to attenuate cardiac remodeling.

Treatment of rats with ANG II caused a significant increase in the phosphorylation and activation of the MAPKs ERK1 and ERK2 compared with rats treated with saline. MAPKs have been implicated in the cellular growth of many cells, including cardiac myocytes (5, 43). ANG II induces cardiac hypertrophy, and its effects involve the activation of the ERK1/2 MAPK pathway. In isolated cardiac myocytes, ANG II increases phospho-ERK1/2 (1, 43). In contrast, the ANG peptides had no effect on total MEK1/2, indicating that the decrease in phospho-ERK is not due to downregulation of the MAPK kinases that phosphorylate and activate ERK1/2. Although ANG-(1–7) alone had no effect on the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, coinfusion of the heptapeptide with ANG II significantly reduced the ANG II-stimulated increase in phospho-ERK1/2. We have previously reported that ANG-(1–7) inhibits mitogen stimulation of ERK1 and ERK2 in isolated vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) (41) and in cultured neonatal cardiac myocytes (43). Since phosphorylation and activation of ERK1 and ERK2 promote the growth of cardiomyocytes, these results suggest that ANG-(1–7) plays a protective role in hypertensive cardiac remodeling by attenuating growth-promoting signaling pathways in the heart.

The ANG-(1–7)-mediated inhibition of MAPK signaling in VSMCs was prevented by pretreatment with either a serine/threonine or tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor, suggesting that ANG-(1–7) upregulates a protein phosphatase to inhibit ERK1/2 activity (15). In response to MAPK activation, MAPK phosphatases are transcriptionally induced to dephosphorylate and inactivate p38, JNK, and ERK MAPKs (22). DUSP-1, also known as MKP-1, is an important member of this family of phosphatases; in the heart, this enzyme, located in the nucleus, regulates the inactivation of nuclear ERK1 and ERK2 as well as p38 and JNK (4). DUSP-1 was increased in the LVs of rats treated with ANG-(1–7), alone or in the presence of ANG II, suggesting that ANG-(1–7) upregulates DUSP-1. This result suggests that the observed reduction in phospho-ERK1/2 was due to the elevation of DUSP-1 by ANG-(1–7). However, it is important to note that these MAPKs are substrates for other phosphatases, and further study is needed to determine whether DUSP-1 is solely responsible for the dephosphorylation after the administration of the heptapeptide hormone. In addition, DUSP-1 mRNA was increased in the ventricles of rats treated with ANG-(1–7), in the presence or absence of ANG II, indicating that the regulation of DUSP-1 occurred at transcription or mRNA stability. In cultured cardiac myocytes in which DUSP-1 was constitutively expressed, Bueno et al. (4) showed that phosphorylation and activation of p38, JNK, or ERK1/ERK2 were blocked and that catecholamine-induced cardiac hypertrophy was attenuated. In addition, transgenic mice with constitutive expression of physiological levels of DUSP-1 (MKP-1) in the heart showed no phosphorylation/activation of cardiac p38, JNK, or ERK1/ERK2, whereas hypertrophy in response to aortic banding or catecholamine infusion was attenuated, demonstrating that DUSPs, particularly DUSP-1, are important in counterbalancing regulatory MAPKs in the heart (4). These results are in agreement with our findings showing that ANG-(1–7) upregulates DUSP-1, which is associated with a reduction in MAPK activity and may contribute to the attenuation of cardiac myocyte hypertrophy in vivo.

ANG-(1–7) also activates other phosphatases, including both tyrosine phosphatases and the phosphoinositide phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN). Src homology 2-containing protein-tyrosine phosphatase (SHP)-1, was increased in ANG-(1–7)-stimulated proximal tubule cells (16) and in the heart of fructose-fed rats after administration of the heptapeptide (17). Phosphorylation of the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 was increased by ANG-(1–7) in human endothelial cells, and small interfering (si)RNA-mediated reduction of endothelial cell SHP-2 was associated with an increase in the phosphorylation of c-Src, demonstrating that SHP-2 dephosphorylates Src kinase (35). In transgenic mice that constitutively overexpress cardiac ANG-(1–7), SHP-2 was increased in the ventricles of the heart, in association with reduced cardiac hypertrophy and decreased phosphorylation of Src and p38 MAPK (30). Although ANG II treatment decreased SHP-2 activity in control mice, SHP-2 activity in response to ANG II infusion was not reduced in mice that overexpress cardiac ANG-(1–7), in agreement with the increase in SHP-2 immunoreactivity. In addition, PTEN, which dephosphorylates phosphoinositide-containing phospholipids to prevent membrane recruitment of Akt, was increased in rat neurons after ANG-(1–7) treatment (31). More recently, we (7) showed that ANG-(1–7) upregulated DUSP-1 in tumor-associated fibroblasts with an associated decrease in MAPK phosphorylation. These results suggest that the regulation of cellular phosphatases may be a primary mechanism whereby ANG-(1–7) mediates a variety of biological effects.

We showed that cardiac myocytes contain the Mas receptor and that the ANG-(1–7)-mediated decrease in the phosphorylation of ERK1 and ERK2 was blocked when the Mas receptor was reduced using siRNAs (43). However, the molecular mechanism by which ANG-(1–7) stimulation of the Mas receptor increases DUSP-1 is not clear. Dias-Peixoto et al. (9) showed that ANG-(1–7) increased the production of nitric oxide (NO) in isolated adult myocytes, in association with an increase in endothelial NO synthase and Akt signaling; the responses were blocked by a Mas receptor antagonist or using myocytes from Mas-deficient mice, indicating that the effects were mediated by the Mas receptor. In transgenic rats with a lifetime increase in circulating ANG-(1–7), the increase in cardiac hypertrophy (including elevations in heart weight, myocyte CSA, and hypertrophic genes) were blunted in association with an increase in neuronal NO synthase (19). In addition, ANG-(1–7) increased NO production in isolated myocytes, an effect that was blocked by the NO synthase inhibitor NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester or a guanylate cyclase inhibitor, suggesting that the effects of the heptapeptide are mediated by NO/cGMP. In VSMCs, the insulin-induced increase in DUSP-1 (MKP-1) was blocked by pretreatment with inhibitors of the NO/cGMP pathway in association with restoration of PDGF-stimulated migration,(27) suggesting that DUSP-1 expression is regulated by an increase in cGMP. The ANP-mediated increase in DUSP-1 (MKP-1) in glomerular mesangial cells was mimicked by 8-bromo-cGMP or sodium nitroprusside, suggesting that ANP increases DUSP-1 by activation of the NO/cGMP pathway (40). These results suggest that ANG-(1–7) may upregulate DUSP-1 in cardiac myocytes by stimulating NO production and the guanylate cyclase-mediated increase in cGMP. Alternatively, we (41) have shown that ANG-(1–7) increases cAMP in VSMCs and that attenuation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase blocked cell growth. These results suggest that ANG-(1–7) may upregulate DUSP-1 by the Mas-mediated activation of cGMP or cAMP and the associated cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinase.

In conclusion, we showed that ANG-(1–7) prevents cardiac remodeling in association with upregulation of DUSP-1 and inhibition of the ERK1/2 MAPK pathway. The protective effect of ANG-(1–7) was not accompanied by lower blood pressure, supporting the hypothesis that the actions of ANG-(1–7) are mediated through direct effects on cardiac myocytes. Although various intracellular signaling pathways are involved in the regulation of cardiac hypertrophy, activation of MAPKs and their inactivation by MAPK phosphatases are central pathways necessary for the initiation and maintenance of cardiac hypertrophy. Thus, MAPKs or MAPK phosphatases are ideal pharmacological targets to treat maladaptive cardiac myocyte hypertrophy of numerous origins. Collectively, these results suggest that ANG-(1–7) plays a cardioprotective role in hypertension and that strategies to increase ANG-(1–7) may be effective in the treatment of the hypertensive heart.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-51952. In addition, this work was supported, in part, by Unifi Incorporated (Greensboro, NC) and the Farley-Hudson Foundation (Jacksonville, NC).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: L.T.M., P.E.G., and E.A.T. conception and design of research; L.T.M. performed experiments; L.T.M., P.E.G., and E.A.T. analyzed data; L.T.M., P.E.G., and E.A.T. interpreted results of experiments; L.T.M., P.E.G., and E.A.T. prepared figures; L.T.M. drafted manuscript; L.T.M., P.E.G., and E.A.T. edited and revised manuscript; L.T.M., P.E.G., and E.A.T. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of L. Tenille Shields, Mark Landrum, and Robert Lanning.

Present address of L. T. McCollum: Mount Sinai School of Medicine, One Gustave L. Levy Place, New York, NY 10029.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aoki H, Richmond M, Izumo S, Sadoshima J. Specific role of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway in angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy in vitro. Biochem J 347: 275–284, 2000 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Averill DB, Ishiyama Y, Chappell MC, Ferrario CM. Cardiac angiotensin-(1–7) in ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 108: 2141–2146, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benter IF, Ferrario CM, Morris M, Diz DI. Antihypertensive actions of angiotensin-(1–7) in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 269: H313–H319, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bueno OF, De Windt LJ, Lim HW, Tymitz KM, Witt SA, Kimball TR, Molkentin JD. The dual-specificity phosphatase MKP-1 limits the cardiac hypertrophic response in vitro and in vivo. Circ Res 88: 88–96, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bueno OF, Molkentin JD. Involvement of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 in cardiac hypertrophy and cell death. Circ Res 91: 776–781, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cassis LA, Marshall DE, Fettinger MJ, Rosenbluth B, Lodder RA. Mechanisms contributing to angiotensin II regulation of body weight. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 274: E867–E876, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cook KL, Metheny-Barlow LJ, Tallant EA, Gallagher PE. Angiotensin-(1–7) reduces fibrosis in orthotopic breast tumors. Cancer Res 70: 8319–8328, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. De Mello WC. Angiotensin (1–7) re-establishes impulse conduction in cardiac muscle during ischaemia-reperfusion. The role of the sodium pump. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 5: 203–208, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dias-Peixoto MF, Santos RA, Gomes ER, Alves MN, Almeida PW, Greco L, Rosa M, Fauler B, Bader M, Alenina N, Guatimosim S. Molecular mechanisms involved in the angiotensin-(1–7)/Mas signaling pathway in cardiomyocytes. Hypertension 52: 542–548, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Diz DI, Baer PG, Nasjletti A. Angiotensin II-induced hypertension in the rat. Effects on the plasma concentration, renal excretion, and tissue release of prostaglandins. J Clin Invest 72: 466–477, 1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferrario CM, Chappell MC, Tallant EA, Brosnihan KB, Diz DI. Counterregulatory actions of angiotensin-(1–7). Hypertension 30: 535–541, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ferreira AJ, Santos RA, Almeida AP. Angiotensin-(1–7): cardioprotective effect in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. Hypertension 38: 665–668, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ferreira AJ, Santos RA, Almeida AP. Angiotensin-(1–7) improves the post-ischemic function in isolated perfused rat hearts. Braz J Med Biol Res 35: 1083–1090, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Freeman EJ, Chisolm GM, Ferrario CM, Tallant EA. Angiotensin-(1–7) inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell growth. Hypertension 28: 104–108, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gallagher PE, Ferrario CM, Tallant EA. MAP kinase/phosphatase pathway mediates the regulation of ACE2 by angiotensin peptides. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295: C1169–C1174, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gava E, Samad-Zadeh A, Zimpelmann J, Bahramifarid N, Kitten GT, Santos RA, Touyz RM, Burns KD. Angiotensin-(1–7) activates a tyrosine phosphatase and inhibits glucose-induced signalling in proximal tubular cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 1766–1773, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Giani JF, Mayer MA, Munoz MC, Silberman EA, Hocht C, Taira CA, Gironacci MM, Turyn D, Dominici FP. Chronic infusion of angiotensin-(1–7) improves insulin resistance and hypertension induced by a high-fructose diet in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296: E262–E271, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Giani JF, Munoz MC, Mayer MA, Veiras LC, Arranz C, Taira CA, Turyn D, Toblli JE, Dominici FP. Angiotensin-(1–7) improves cardiac remodeling and inhibits growth-promoting pathways in the heart of fructose-fed rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H1003–H1013, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gomes ER, Lara AA, Almeida PW, Guimaraes D, Resende RR, Campagnole-Santos MJ, Bader M, Santos RA, Guatimosim S. Angiotensin-(1–7) prevents cardiomyocyte pathological remodeling through a nitric oxide/guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate-dependent pathway. Hypertension 55: 153–160, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grobe JL, Mecca AP, Lingis M, Shenoy V, Bolton TA, Machado JM, Speth RC, Raizada MK, Katovich MJ. Prevention of angiotensin II-induced cardiac remodeling by angiotensin-(1–7). Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H736–H742, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grobe JL, Mecca AP, Mao H, Katovich MJ. Chronic angiotensin-(1–7) prevents cardiac fibrosis in DOCA-salt model of hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H2417–H2423, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haneda M, Sugimoto T, Kikkawa R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase: a negative regulator of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Eur J Pharmacol 365: 1–7, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hayashi D, Kudoh S, Shiojima I, Zou Y, Harada K, Shimoyama M, Imai Y, Monzen K, Yamazaki T, Yazaki Y, Nagai R, Komuro I. Atrial natriuretic peptide inhibits cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 322: 310–319, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Iwata M, Cowling RT, Gurantz D, Moore C, Zhang S, Yuan JX, Greenberg BH. Angiotensin-(1–7) binds to specific receptors on cardiac fibroblasts to initiate antifibrotic and antitrophic effects. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H2356–H2363, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Iyer SN, Chappell MC, Averill DB, Diz DI, Ferrario CM. Vasodepressor actions of angiotensin-(1–7) unmasked during combined treatment with lisinopril and losartan. Hypertension 31: 699–705, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Iyer SN, Ferrario CM, Chappell CM. Angiotensin-(1–7) contributes to the antihypertensive effects of blockade of the renin-angiotensin system. Hypertension 31: 356–361, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jacob A, Molkentin JD, Smolenski A, Lohmann SM, Begum N. Insulin inhibits PDGF-directed VSMC migration via NO/cGMP increase if MPK-1 and its inactivation of MAPKs. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 283: C704–C713, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Loot AE, Roks AJ, Henning RH, Tio RA, Suurmeijer AJ, Boomsma F, van Gilst WH. Angiotensin-(1–7) attenuates the development of heart failure after myocardial infarction in rats. Circulation 105: 1548–1550, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193: 265–275, 1951 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mercure C, Yogi A, Callera GE, Aranha AB, Bader M, Ferreira AJ, Santos RA, Walther T, Touyz RM, Reudelhuber TL. Angiotensin(1–7) blunts hypertensive cardiac remodeling by a direct effect on the heart. Circ Res 103: 1319–1326, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Modgil A, Zhang Q, Yao F, O'Rourke ST, Sun C. Angiotensin (1–7) attenuates the pressor response to angiotensin II via stimulation of PTEN in the RVLM of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 56: e132, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Owens DM, Keyse SM. Differential regulation of MAP kinase signaling by dual-specificity phosphatases. Oncogene 26: 3203–3213, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pei Z, Meng R, Li G, Yan G, Xu C, Zhuang Z, Ren J, Wu Z. Angiotensin-(1–7) ameliorates myocardial remodeling and interstitial fibrosis in spontaneous hypertension: role of MMPs/TIMPs. Toxicol Lett 199: 173–181, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sadoshima J, Qiu Z, Morgan JP, Izumo S. Angiotensin II and other hypertrophic stimuli mediated by G protein-coupled receptors activate tyrosine kinase, mitogen-activated protein kinase, and 90-kD S6 kinase in cardiac myocytes. The critical role of Ca2+-dependent signaling. Circ Res 76: 1–15, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sampaio WO, de Castro CH, Santos RAS, Schriffin EL, Touyz RM. Angiotensin-(1–7) counterregulates angiotensin II signaling in human endothelial cells. Hypertension 50: 1093–1098, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Santiago NM, Guimaraes PS, Sirvente RA, Oliveira LA, Irigoyen MC, Santos RA, Campagnole-Santos MJ. Lifetime overproduction of circulating angiotensin-(1–7) attenuates deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension-induced cardiac dysfunction and remodeling. Hypertension 55: 889–896, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Santos RA, Brum JM, Brosnihan KB, Ferrario CM. The renin-angiotensin system during acute myocardial ischemia in dogs. Hypertension 15: I121–I127, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Santos RA, Ferreira AJ, Nadu AP, Braga AN, de Almeida AP, Campagnole-Santos MJ, Baltatu O, Iliescu R, Reudelhuber TL, Bader M. Expression of an angiotensin-(1–7)-producing fusion protein produces cardioprotective effects in rats. Physiol Genomics 17: 292–299, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Strawn WB, Ferrario CM, Tallant EA. Angiotensin-(1–7) reduces smooth muscle growth after vascular injury. Hypertension 33: 207–211, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sugimoto T, Kikkawa R, Haneda M, Shigeta Y. Atrial natriuretic peptide inhibits endothelin-1-induced activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in cultured rat mesangial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 195: 72–78, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tallant EA, Clark MA. Molecular mechanisms of inhibition of vascular growth by angiotensin-(1–7). Hypertension 42: 574–579, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tallant EA, Diz DI, Ferrario CM. State-of-the-Art lecture. Antiproliferative actions of angiotensin-(1–7) in vascular smooth muscle. Hypertension 34: 950–957, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tallant EA, Ferrario CM, Gallagher PE. Angiotensin-(1–7) inhibits growth of cardiac myocytes through activation of the mas receptor. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H1560–H1566, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wei CC, Ferrario CM, Brosnihan KB, Farrell DM, Bradley WE, Jaffa AA, Dell'Italia LJ. Angiotensin peptides modulate bradykinin levels in the interstitium of the dog heart in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 300: 324–329, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]