Abstract

Oxidative damage and impaired cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyto) handling are associated with mitochondrial [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]mito) overload and depressed functional recovery after cardiac ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury. We hypothesized that hearts from old guinea pigs would demonstrate impaired [Ca2+]mito handling, poor functional recovery, and a more oxidized state after I/R injury compared with hearts from young guinea pigs. Hearts from young (∼4 wk) and old (>52 wk) guinea pigs were isolated and perfused with Krebs-Ringer solution (2.1 mM Ca2+ concentration at 37°C). Left ventricular pressure (LVP, mmHg) was measured with a balloon, and NADH, [Ca2+]mito (nM), and [Ca2+]cyto (nM) were measured by fluorescence with a fiber optic probe placed against the left ventricular free wall. After baseline (BL) measurements, hearts were subjected to 30 min global ischemia and 120 min reperfusion (REP). In old vs. young hearts we found: 1) percent infarct size was lower (27 ± 9 vs. 57 ± 2); 2) developed LVP (systolic-diastolic) was higher at 10 min (57 ± 11 vs. 29 ± 2) and 60 min (55 ± 10 vs. 32 ± 2) REP; 3) diastolic LVP was lower at 10 and 60 min REP (6 ± 3 vs. 29 ± 4 and 3 ± 3 vs. 21 ± 4 mmHg); 4) mean [Ca2+]cyto was higher during ischemia (837 ± 39 vs. 541 ± 39), but [Ca2+]mito was lower (545 ± 62 vs. 975 ± 38); 5) [Ca2+]mito was lower at 10 and 60 min REP (129 ± 2 vs. 293 ± 23 and 122 ± 2 vs. 234 ± 15); 6) reduced inotropic responses to dopamine and digoxin; and 7) NADH was elevated during ischemia in both groups and lower than BL during REP. Contrary to our stated hypotheses, old hearts showed reduced [Ca2+]mito, decreased infarction, and improved basal mechanical function after I/R injury compared with young hearts; no differences were noted in redox state due to age. In this model, aging-associated protection may be linked to limited [Ca2+]mito loading after I/R injury despite higher [Ca2+]cyto load during ischemia in old vs. young hearts.

Keywords: aging, cardiac calcium handling, guinea pigs, ischemia-reperfusion injury

today there are 35 million people over the age of 65 in the United States, and this number is predicted to double by the year 2030 (21). The aging heart is characterized by alterations in both structure and function. The incidence and prevalence of coronary artery disease, hypertension, congestive heart failure, and stroke increases proportionately with age (22). The complex mechanisms of aging in the heart are not clear, but recent evidence strongly suggests that the aging process in heart muscle is due, in large part, to accumulated oxidative damage (3). Because mitochondria are a primary source of oxygen free radicals, aging-induced impairment of mitochondrial bioenergetics (23) has been implicated as a major factor in depressing cardiac function with aging.

Studies in rodent models have shown that cardiac aging is associated with prolonged cardiac contraction, prolonged cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyto) transients, changes in myosin isoform expression, and depressed β-adrenergic contractile response (16, 17, 20, 36). Previous work in atrial muscle from aged rats suggests that they are more susceptible to digoxin-induced cardiotoxicity; however, inotropic efficacy before the onset of toxicity was not affected by age (19). Other studies have shown greater cardiac damage after ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury in hearts isolated from old Fisher 344 rats compared with those from young rats (24). It has also been reported that older guinea pig, rat, and mouse hearts are less sensitive to cardioprotective strategies such as ischemic or anesthetic preconditioning compared with younger hearts (5, 7, 31, 33, 34). Other reports indicate that aging exacerbates apoptosis (25) and cardiac damage after ischemia (18); however, not all studies have observed increased infarct size in aged rats (32, 34).

The guinea pig heart model is more relevant to the clinical situation in humans because, unlike rat or mouse heart models, guinea pig hearts share the following similarities with human hearts: 1) the plateau of the cardiac action potential is longer, 2) cardiac contraction is primarily dependent on Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, and 3) the predominant slow V3 myosin isoform predominates (11). It remains unknown if cardiac function, cardiac mitochondrial bioenergetics, or drug responses are altered more or less in hearts from young vs. old guinea pigs after I/R injury.

In this study, we examined the effects of I/R injury and inotropic interventions to differentially alter [Ca2+]cyto and mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]mito) handling in hearts from young and old guinea pigs. We hypothesized that 1) aging-induced impaired [Ca2+]cyto and [Ca2+]mito handling results in greater ischemic damage and poorer return of function after I/R injury in old vs. young guinea pig isolated hearts, and 2) older hearts are less sensitive to inotropic stimulation than are young hearts.

METHODS

Isolated heart preparation.

The investigation conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals from the National Institutes of Health (NIH No. 85–23, revised 1996). Prior approval was obtained from the Medical College of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Intact, beating hearts from young (∼4 wk, n = 37) and old (>52 wk, n = 37) guinea pigs were prepared by the Langendorff method and perfused with Krebs-Ringer (KR) solution as previously described by us in detail (1, 2, 9, 10, 35, 37, 38). Specifically, 10 mg/kg of ketamine and 5 ml/kg of 1,000 U/ml of heparin were injected intraperitoneally into albino English short-haired guinea pigs 15 min before the animals were decapitated when unresponsive to noxious stimulation. After thoracotomy, the inferior and superior venae cavae were ligated, and the aorta was cannulated distal to the aortic valve. Each heart was immediately perfused via the aortic root with a cold oxygenated, modified KR solution (equilibrated with 97% O2 and 3% CO2) at an aortic root perfusion pressure of 55 mmHg and was then rapidly excised. The KR perfusate (pH 7.39 ± 0.01, Po2 560 ± 10 mmHg) was filtered (5 μm pore size) in-line and had the following calculated composition (in mM, nonionized): 138 Na+, 4.5 K+, 1.2 Mg2+, 2.5 Ca2+, 134 Cl−, 15 HCO3−, 1.2 H2PO4−, 11.5 glucose, 2 pyruvate, 16 mannitol, 0.05 EDTA, 0.1 probenecid, and 5 U/l insulin. Perfusate and bath temperatures were maintained at 37.2 ± 0.1°C using a thermostatically controlled water circulator.

Left ventricular pressure (LVP) was measured isovolumetrically with a transducer connected to a thin, saline-filled latex balloon inserted in the LV through the mitral valve from a cut in the left atrium. Balloon volume was initially adjusted to a diastolic LVP of 0 mmHg so that any subsequent increase in diastolic LVP reflected an increase in left ventricular (LV) wall stiffness or diastolic contracture. Because older guinea pig hearts were significantly larger than hearts of younger guinea pigs (4.0 ± 0.5 vs. 1.6 ± 0.5 g), two different balloon sizes were used to measure LVP. Pairs of bipolar electrodes were placed in the right atrial appendage and right ventricular apex to monitor heart rate. Coronary flow (aortic inflow) was measured by an ultrasonic flowmeter (Transonic T106X) placed directly in the aortic inflow line, as described previously (1, 2, 9, 10, 35, 37, 38), and perfusion pressure was maintained at 55 mmHg.

Measurement of [Ca2+]cyto, NADH, and [Ca2+]mito.

Experiments were carried out in a light-blocking Faraday cage. The heart was partially immobilized by hanging it from the aortic cannula, the pulmonary artery catheter, and the LV balloon catheter. The heart was immersed continuously in the KR bath at 37°C. The distal end of a trifurcated fiber silica fiber optic cable (optical surface area 3.85 mm2) was placed gently against the LV epicardial surface through a hole in the bath. A rubber O ring was placed over the fiber optic tip to seal the hole, and netting was applied around the heart for optimal contact with the fiber optic tip. This maneuver did not affect LVP. Background autofluorescence (AF) was determined for each heart after initial perfusion and stabilization at 37°C.

Indo 1-AM (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO), a Ca2+ indicator, was freshly dissolved in 1 ml of dimethyl sulfoxide containing 16% (wt/vol) Pluronic I-127 (Sigma Chemical) and diluted to 165 ml with modified KR solution. Each heart was then loaded with indo-1 AM for 30 min with the recirculated KR solution at a final indo-1 AM concentration of 6 μM. Loading was stopped when the fluorescence intensity at 405 nm (F405) increased by ∼10-fold. Probenecid (100 μM) was present in the perfusate to retard cell leakage of indo-1. Residual interstitial indo-1 AM was washed out by perfusing the heart with normal KR perfusate for another 20 min. We have reported that loading and washout of indo-1 reduces LVP up to 25%; this effect is due to the vehicle and to cytosolic Ca2+ buffering by indo-1 (35).

F405 and fluorescence emission at 460 nm (F460) were recorded using a modified luminescence spectrophotometer (PTI spectrofluorometer, London, Ontario, Canada). The LV region of the heart was excited with light from a xenon arc lamp, and the light was filtered through a 350-nm monochromator with a bandwidth of 16 nm. The beam was focused on the ingoing fibers of the optic bundle. The arc lamp shutter was opened only for 2.5-s recording intervals to prevent photobleaching. Emission fluorescence was collected by fibers of the remaining two limbs of the cable and filtered by square interference filters (Chroma Technology, Bellows Falls, VT) at 405 and 460 nm. Time control studies have shown that developed LVP remains stable for hearts in both age groups, and, although F405 and F460 decline over time, the F405-to-F460 ratio remains stable, indicating no change in effective measured Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]) in both young and old hearts (data not shown). The F405-to-F460 ratio was converted to [Ca2+]cyto after corrections to account for the noncytosolic fraction as described previously (1, 8, 29, 30).

Tissue AF is an accepted method to measure NADH in isolated hearts. Although AF could also arise from unknown intracellular constituents or cytosolic NADH, the majority comes from the mitochondrial compartment (6, 29, 30). This technique for measuring tissue NADH AF uses the same excitation and emission wavelengths as those used to measure [Ca2+] except that the heart is only loaded with vehicle solution only and not the indo-1 AM dye. After excitation at 350 nm, the emission ratio F460/F405 is interpreted as a relative measure of NADH.

Experimental protocol.

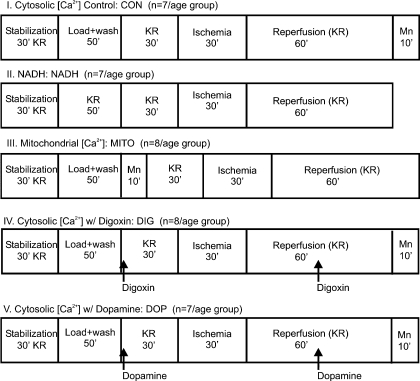

There were five experimental groups comprising young and old guinea pigs of either sex (Fig. 1). Table 1 provides the vital statistics of each of the age groups. Young guinea pigs were <4 wk old, whereas the old guinea pigs were comprised of retired breeders who were >52 wk old. The young guinea pigs were significantly smaller and had lower heart weights than the old guinea pigs.

Fig. 1.

The study consisted of 5 experimental protocol groups as shown. Each protocol consisted of an approximately equal number of randomly assigned old and young guinea pigs, males and females. Protocols I, II, and III were used to address hypothesis 1, and protocols I, IV, and V were used to address hypothesis 2. Each protocol started with a 30-min stabilization period. In protocols to measure Ca2+, the stabilization period was followed by a 50-min dye loading and washout period (baseline, BL). In the protocol to measure mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]mito), MnCl2 was infused after dye washout for 10 min to quench the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyto) fraction; in the protocol to measure [Ca2+]cyto, this procedure was done at the end of the protocol. After a 30-min period of perfusion with Krebs-Ringer (KR) solution, all hearts were subjected to 30 min global ischemia followed by 120 min reperfusion. [Ca2+], Ca2+ concentration.

Table 1.

Guinea pig characteristics

| Young | Old | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, wk | ∼4 | >52 (retired breeders) |

| Body wt, g | 298 ± 64 | 1,164 ± 86* |

| Heart wt, g | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 0.5* |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 269 ± 6 | 213 ± 6* |

Values are means ± SE.

P < 0.05, old vs. young.

Young and old guinea pigs were randomly assigned to one of the five experimental groups as shown in Fig. 1; the order of experiments was randomized. After a 30-min stabilization period, hearts were loaded with indo-1 AM dissolved in the vehicle, or only the vehicle. This was followed by a 20-min washout period. In the [Ca2+]mito measurement group, protocol III, hearts were perfused with MnCl2 for 10 min after dye washout to quench [Ca2+]cyto. A baseline (BL) recording was made at the end of the washout period. Next, hearts were perfused with KR for 30 min followed by a 30-min global no-flow ischemia and a 120-min reperfusion (REP) period. In two groups, protocols IV and V, hearts were perfused either with 1 μM digoxin or 5 μM dopamine (drug concentrations at their 50% effective dose) for 2 min before and after 30 min of global ischemia. At the end of each experiment to measure [Ca2+]cyto, protocols I, IV, and V, 100 μM MnCl2 was perfused for 10 min to quench cytosolic indo 1 Ca2+ transients to calculate and correct for the noncytosolic Ca2+ contribution (mostly mitochondrial). At the end of every experiment (120 min REP), hearts were removed, and atria were discarded. Ventricles were cut into thin transverse sections of ∼3 mm thickness and immersed in 1% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride to measure infarct size by differential staining (1).

Protocols I, II, and III (Fig. 1) were used to address our first hypothesis that old hearts would exhibit greater functional damage and poorer Ca2+ handling compared with young hearts during I/R injury. Protocols I, IV, and V (Fig. 1) addressed our second hypothesis that old hearts would be less sensitive to inotropic stimulation before and after I/R injury than young hearts. Each experiment lasted 270 min except when NADH was assessed, since these hearts were not exposed to MnCl2; consequently, the NADH experiments were 260 min in duration.

Data collection and presentation.

All analog signals were digitized (PowerLab 16/30; AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO) and recorded at 200 Hz (Chart & Scope version 5.3) on Power Macintosh G4 computers for later analysis using customized software developed in MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Seattle, WA). The following indexes were calculated: developed LVP (mmHg) (systolic − diastolic LVP); diastolic LVP; mean [Ca2+]cyto (nM); [Ca2+]mito (nM); NADH (afu); coronary flow (ml·min−1·g−1); and ventricular infarct size (% by weight). Except for infarct size, results for functional data are reported for up to 60 min REP because there were no further changes between 60 and 120 min REP.

Statistical analysis.

All indexes were expressed as means ± SE and were compared between age groups and within each age group at BL, at 30 min ischemia, and at 10 and 60 min REP. Differences among indexes were determined by two-way ANOVA for repeated measures (MINITAB Statistical Software Release 13.3); when F-tests were significant, the Student-Newman-Keul's post hoc was used to compare means. Mean values were considered significantly different at P < 0.05 (2-tailed).

RESULTS

Table 1 compares BL characteristics of young and old guinea pigs of equal numbers of males and females. Young animals (∼4 wk old) were smaller in size with smaller hearts than old animals (>52 wk old). Spontaneous resting heart rate was higher in young hearts than in old hearts.

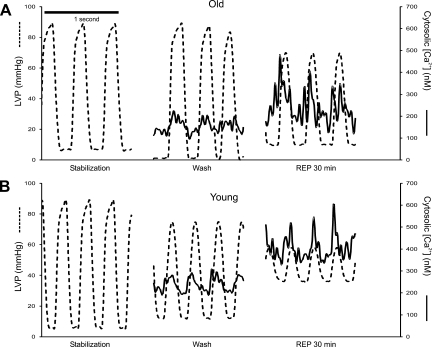

Figure 2 shows simultaneously obtained representative LVP and [Ca2+]cyto transients after stabilization, and before and after I/R injury in old and young hearts. Note the higher systolic and lower diastolic LVP and mean [Ca2+]cyto during REP in the old vs. young hearts.

Fig. 2.

Representative tracings of [Ca2+]cyto (axis on right, solid line) and left ventricle pressure (LVP) time series (axis on left, dashed line) over 1 s in old (A) and young (B) hearts during stabilization, 30 min before ischemia, and 30 min after reperfusion (REP). Note that, during reperfusion after ischemia, there was an increase in systolic and diastolic [Ca2+]cyto in both young and old hearts but that the old hearts showed better functional recovery than young hearts.

Effect of age on cytosolic Ca2+ handling and contractile function.

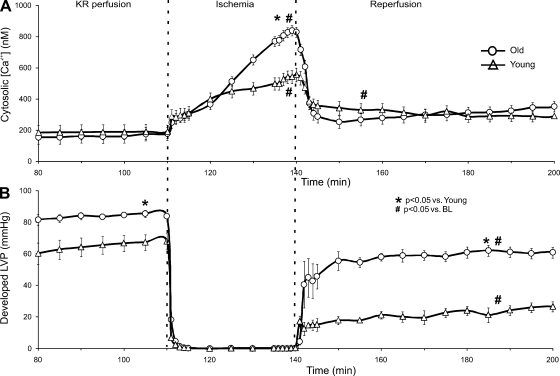

Mean [Ca2+]cyto and developed (phasic) LVP were measured at intervals throughout the protocol (Fig. 3). Mean [Ca2+]cyto was similar in young and old hearts after dye washout. During ischemia, [Ca2+]cyto increased more in old hearts than in young hearts. [Ca2+]cyto was significantly higher during REP compared with preischemic levels for both groups. However, there was no difference in mean [Ca2+]cyto between young and old hearts throughout REP. Developed LVP was similar before dye loading and washout for young and old hearts, but indo-1 loading and washout resulted in a lower developed LVP in young vs. old hearts. After I/R injury, all hearts demonstrated significantly reduced developed LVP compared with BL (after dye washout); however, this was more pronounced in young than in old hearts, even if normalized to BL. At REP 10 and REP 60 min, old hearts exhibited lower diastolic LVP compared with young hearts (6 ± 3 vs. 29 ± 4 and 3 ± 3 vs. 21 ± 4 mmHg).

Fig. 3.

Average [Ca2+]cyto (A) and simultaneously recorded developed LVP (B) for young and old hearts. Data are shown from 80 min into the experiment after dye loading and washout. After the stabilization period, no differences were noted between old and young hearts in developed LVP (85.2 ± 2.0 vs. 85.6 ± 1.7 mmHg; data not shown). The negative inotropic effects of indo-1 AM loading were greater in young hearts compared with old hearts as noted from the lower developed LVP after dye washout. Average [Ca2+]cyto was lower in old hearts than in young hearts at REP 10 min but not at REP 60 min. Developed LVP was higher in old hearts than in young hearts at REP 10 min and at REP 60 min.

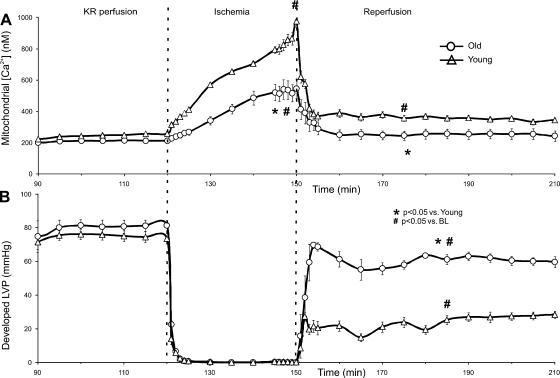

Effect of age on mitochondrial Ca2+ handling and contractile function.

Developed LVP was higher on REP in old vs. young hearts as also shown in Fig. 3. Young hearts demonstrated substantially greater [Ca2+]mito loading than old hearts throughout I/R (Fig. 4). Furthermore, [Ca2+]mito remained higher during REP than preischemic levels in young but not old hearts. So, despite old hearts demonstrating a larger increase in [Ca2+]cyto during I/R compared with young hearts, [Ca2+]mito loading was considerably lower in old vs. young hearts after I/R injury. This suggests that old hearts resist an increase in [Ca2+]mito when challenged by I/R injury. Any indo-1-bound Ca2+ in infarcted tissue (nonviable cells) should be washed away during REP; although the total Ca2+ signal may decrease, the bound/unbound ratiometric technique reflects the viable cell content of both cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+.

Fig. 4.

Average [Ca2+]mito (A) and simultaneously recorded developed LVP (B) from young and old hearts before, during, and after ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury. Old hearts exhibited less [Ca2+]mito loading during ischemia than young hearts. Old hearts also exhibited less [Ca2+]mito loading after 60 min REP compared with young hearts. Before ischemia, no differences were observed in developed LVP between old and young hearts. However, throughout REP, developed LVP in young hearts was lower than that observed in old hearts.

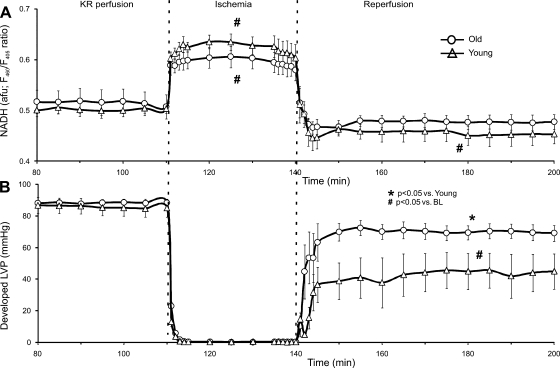

Effect of age on redox state and contractile function.

NADH levels increased during ischemia and dropped below preischemic levels during REP in both young and old hearts (Fig. 5). However, no differences in NADH were noted before, during, or after ischemia between young and old hearts. There was no difference in developed LVP between young and old hearts before ischemia in the NADH group. However, after I/R injury, old hearts demonstrated higher values of developed LVP compared with young hearts. This finding indicates that the indo-1-induced drop in developed LVP before ischemia, as noted in Fig. 3, while differently affecting young vs. old hearts, did not contribute to the better functional return on REP in old compared with young hearts. Additionally, the developed LVP data shown collected during measurement of [Ca2+]mito (Fig. 4) also demonstrates that, after the cytosolic fraction of indo-1 was quenched with MnCl2 before ischemia, there were no differences in developed LVP between old and young hearts.

Fig. 5.

Average NADH autofluorescence (A) and simultaneously recorded developed LVP (B) for young and old hearts. No differences were noted in developed LVP or redox state between young and old hearts during BL. Both young and old hearts showed increased NADH during ischemia that fell to below BL levels during REP. However, old hearts exhibited better return of developed LVP throughout REP compared with young hearts. F480/F405, ratio of fluorescence emission at 460 vs. 405 nm.

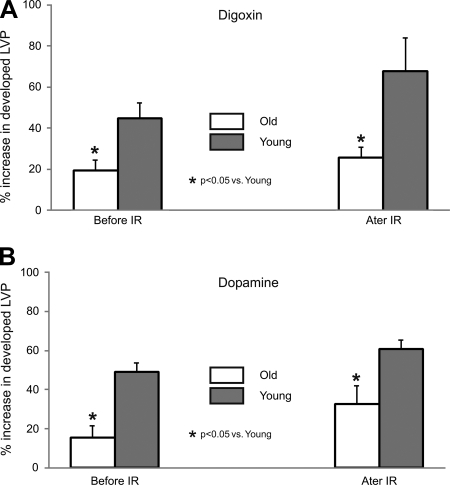

Effect of age on inotropic responses.

Percentage changes in mean developed LVP and [Ca2+]cyto in young and old hearts with inotropic agents, digoxin (Fig. 6A) or dopamine (Fig. 6B), given both before and after ischemia were measured (Fig. 6). Both drugs were administered via bolus injections, and their effects had completely washed out before the onset of ischemia as has been reported earlier (10, 28). Old hearts showed reduced sensitivity to inotropic intervention with a lesser increase in developed LVP despite a higher increase in mean [Ca2+]cyto before and after I/R injury compared with young hearts. Mean developed LVP before and after perfusion of digoxin (Fig. 6A) or dopamine (Fig. 6B) shows that old hearts exhibit a blunted drug-induced increase in developed LVP than young hearts but a higher developed LVP after I/R injury.

Fig. 6.

Percentage increase in developed LVP for old and young hearts exposed to digoxin (A) and dopamine (B) before (compared with BL) and after (compared with REP 30) I/R injury. Both young and old hearts exhibited an increase in developed LVP when exposed to these positive inotropic drugs before and after I/R injury; however, older hearts displayed a blunted response compared with younger hearts.

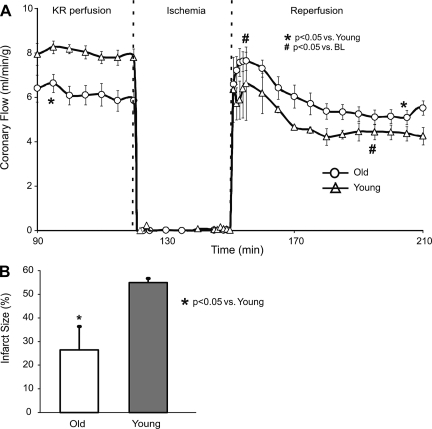

Effect of age on coronary flow and infarct size.

Coronary flow was normalized to heart weight and expressed as milliliters per minute per gram. Old hearts had lower coronary flow per gram before ischemia compared with young hearts (Fig. 7A). After ischemia, coronary flow per gram decreased in young hearts compared with preischemic levels. After ischemia, coronary flow per gram in old hearts increased acutely (reactive hyperemia) but returned to their preischemic levels after 60 min of REP. Overall, on REP, old hearts had a higher coronary flow per gram than young hearts. Infarct size was greater in young hearts than in old hearts (Fig. 7B). In the global ischemia model, the area of infarction is more LV mesomyocardial rather than subendocardial and localized as in a regional model. Together, the coronary flow per gram and infarct size data indicate that old guinea pig hearts recover from ischemia with less myocardial and vascular damage than do young guinea pig hearts.

Fig. 7.

Tissue perfusion results from young and old hearts during, before, and after I/R injury. The coronary flow data were derived from hearts assigned to the experimental group following protocol III to measure [Ca2+]mito. The higher coronary flow per weight (A) suggests that old hearts had better-preserved vascular function than young hearts. Old hearts had a smaller mean infarct size (B) (%ventricular wt) than young hearts after 30 min global ischemia and 120 min REP.

DISCUSSION

The aging heart undergoes extensive structural and functional remodeling that includes changes in coronary vascular and myocardial structure that might contribute to the increased occurrence of cardiovascular diseases seen in the elderly population. Coronary arterial walls become thicker, even in the absence of atherosclerosis, and less compliant; functional changes include altered regulation of vascular tone and responses to vasoactive substances (21). Cardiac structural remodeling consists of increased LV wall thickness and left atrial size related to increased myocyte size; functional changes include a reduced threshold for cell Ca2+ overload, decreased contractility, increased plasma levels of catecholamines, decreased response to adrenergic receptor stimulation, and decreased heart rate variability (3, 16, 23, 36). With aging, isometric myocardial contraction duration is also prolonged, indicating a less compliant myocardium (14). Senescent hearts also demonstrate reduced sensitivity to cardioprotective strategies like ischemic and anesthetic preconditioning (31, 34). However, previous studies have been conducted almost exclusively in mice and with the National Institute of Aging Fischer 344 rat model, which is the model of choice because the rats are bred specifically for research on senescence.

Overall, our study in young and old guinea pig intact hearts show that, contrary to our initial hypotheses, 1) old hearts exhibit better functional return, reduced [Ca2+]mito loading during ischemia and REP (despite a higher [Ca2+]cyto loading), and less infarct size than young hearts, and 2) old hearts demonstrate a reduced sensitivity to inotropic intervention before or after ischemia compared with young hearts compared with other reports (20, 22). Much of the mechanical dysfunction in the young hearts after I/R injury is due to reduced diastolic relaxation (high diastolic LVP); this may be related to the greater [Ca2+]cyto during early REP (Fig. 3). The greater degree of infarction in the young vs. old hearts is not likely due to the lower vasodilatory capacity of the young hearts because hearts of both age groups were reperfused at the same constant coronary pressure.

Aging and Ca2+ loading.

Studies in rats have shown that aging results in an increase in the number and activity of individual L-type Ca2+ channels in the sarcolemma that may lead to an increase in Ca2+ influx into the cytosolic space (36). Prolongation of the Ca2+ transient may also be related to a reduction in active Ca2+ uptake by the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) and/or impaired sarcolemmal Na+/Ca2+ exchange. However, no differences in Ca2+ transient durations or amplitudes in isolated cardiac myocytes were noted between young and old Fischer 344 × Brown Norway F1 hybrid rats (5). Previous models of aging have not furnished information on how hearts from old vs. young animals respond to pathophysiological conditions such as I/R injury and inotropic intervention or how compartmental Ca2+ flux is altered during ischemic injury. Sniecinski and Liu (34) reported that young and old Fischer 344 rats show an increase in intracellular Ca2+, measured using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, when exposed to ischemic insult; however, they were unable to independently assess the cytosolic from the mitochondrial Ca2+ component in their study.

Our results were unexpected in that hearts from old guinea pigs exhibited greater [Ca2+]cyto loading during mid to late ischemia and late REP than young hearts, but they paradoxically exhibited less [Ca2+]mito loading during ischemia and during REP. Moreover, this reduction in [Ca2+]mito loading was associated with better contractile recovery after ischemia and less tissue damage compared with young hearts. These interesting results imply that, in our guinea pig model, old hearts are less susceptible to Ca2+ uptake in the mitochondrial matrix or more capable of Ca2+ extrusion into the cytosolic space.

Aging and altered mitochondrial bioenergetics.

Studies have implicated accumulation of oxidative damage as being directly linked to the aging process (3, 23). In fact, aging appears to decrease mitochondrial respiratory efficiency, which may be a key link to impaired recovery after I/R injury (33). Aerobic oxidation of NADH is significantly decreased in aged rats, which suggests a defect at complex I (NADH quinone oxidoreductase) (23). Other studies suggest that aging alters function at other respiratory complexes (i.e., II-IV) (7). The free radical theory of aging and the mitochondrial DNA theory of aging both implicate mitochondria as producers and targets of reactive oxygen species (ROS) as a basis for altered mitochondrial and thus myocardial function with aging. The theories postulate that random somatic mutations of mitochondrial DNA induced by ROS are responsible for the energy decline associated with senescence (23). Dysfunction at complex I is favored in the mitochondrial DNA theory of aging because seven mitochondrial genes encode for complex I compared with one to three for each of the other respiratory complexes (23).

Our results indicate that, at least in our model, a greater increase in [Ca2+]cyto loading in old vs. young hearts during ischemia does not necessarily lead to a greater increase in [Ca2+]mito loading. The less [Ca2+]mito loading in old hearts compared with young hearts throughout ischemia and REP could imply that there is reduced Ca2+ uptake by the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter and/or enhanced Ca2+ efflux by the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger with aging. Additionally, there was no difference between NADH levels in old and young hearts during I/R, suggesting mitochondria were just as reduced (charged) in old as in young hearts. Future experiments are needed to understand this mechanism of reduced [Ca2+]mito loading in the face of higher [Ca2+]cyto loading, and particularly if there are age-related differences in [Ca2+]mito uptake or extrusion mechanisms.

Aging and extent of I/R injury.

Previous studies have indicated not only that old rat hearts are more susceptible to I/R injury than are young rat hearts but also, unlike their young counterparts, that old hearts do not benefit from cardioprotection afforded by ischemic preconditioning (24, 31, 34). On the other hand, Sniecinski and Liu (34) found that old Fischer 344 rats had smaller cardiac infarct size than young rats after I/R injury. Our results in guinea pig hearts demonstrate that old hearts, subjected to the same duration of global ischemic insult as young hearts, exhibited improved return of function as measured by coronary flow (normalized to heart weight), developed LVP (contractility), diastolic LVP (relaxation), as well as infarct size compared with young hearts. We suggest that life stresses in older guinea pigs better trigger preconditioning or adaptive-type mechanisms that offer a better measure of cardioprotection compared with rats. This may explain, in part, why old hearts responded better to I/R injury and may also explain why, in previous studies, old rat hearts showed no response to ischemic or anesthetic preconditioning (27, 34).

Aging and responsiveness to inotropic drugs.

Jiang et al. (16) reported that aged rats were less sensitive to β-adrenergic stimulation by isoproterenol than young rats. This reduction in contractility was characterized by reduced inotropic and lusitropic effects. This age-related reduction in contractile response to β-adrenergic stimulation was accompanied by attenuated tissue cAMP levels and phosphorylation of phospholamban in the SR and troponin I in the myofibrils. Ferrara et al. (12, 13) have also reported that isolated cardiac myocytes from aged guinea pigs demonstrated a depressed response to isoproterenol compared with those from young guinea pigs. Digoxin, a Na+-K+-ATPase pump inhibitor, remains one of the most commonly used therapeutic drugs to treat congestive heart failure patients, who are mostly elderly and are reported to have a lower tolerance to digoxin-induced cardiotoxicity. Indeed, the reserve capacity of the Na+ pump is reduced in aged ventricular muscle, which might explain the increased sensitivity to cardiac glycosides (19). Dopamine, a hormone that acts on dopaminergic and other adrenergic receptors, is another drug used to stimulate cardiac function.

Our results showed that digoxin or dopamine bolus administration before I/R injury resulted in increases in [Ca2+]cyto and developed LVP in both young and old hearts. The rise in developed LVP was blunted in old hearts compared with young hearts, suggesting age-related loss of inotropic sensitivity. However, the absolute numbers confirm our observations from the control group showing old hearts exhibited better recovery from I/R injury than young hearts. Further assessment of age-related changes in the Ca2+-contraction relationship, mitochondrial bioenergetics, and protein expression during inotropic interventions before and after I/R injury may help to explain how the cardiac myocyte's response to stress is altered with age in different species.

Limitations of the study.

The average life span of a confined, laboratory guinea pig is 7–9 yr. There is a linear relationship between guinea pig age and body weight for the first 12 mo; however, after that, body weight remains relatively constant (4). Guinea pigs younger than 4 wk old had a mean body weight of 298 ± 64 g and were classified as being young. Because laboratory guinea pigs are not bred after 52 wk of age, they do not survive to an older age. Guinea pigs obtained as retired breeders (>52 wk old) had a mean body weight of 1,164 ± 86 g and were classified as being old. Because of the changes in weight/volume with aging, and other factors, it would be more appropriate to study hearts of different ages but of the same average weight. Such a study might be to compare I/R injury in hearts from 1-yr vs. 8-yr-old guinea pigs; unfortunately, this was not possible. Although we did not gender distinguish our animals, there is evidence to suggest that gender plays a role in recovery from ischemia (15). The isolated, perfused heart model used for this study may not totally reflect changes in protection against I/R injury as a function of age in in vivo hearts. Clinically, global cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation or cardiopulmonary arrest, with subsequent resuscitation (REP), does not occur as frequently as regional ischemia and REP because of coronary vessel obstruction or spasm. It is possible there may be some differences in age-induced cardiac function and damage in a global model vs. a regional model. Unfortunately, the measurements of [Ca2+] and NADH require the selected model to establish the relationships between [Ca2+]cyto and cardiac function and between NADH and [Ca2+]mito. The measure of noncytosolic [Ca2+] using the Mn2+ quenching technique may overestimate [Ca2+]mito because [Ca2+] in other organelles is also registered (26).

In summary, our isolated heart model demonstrates that old guinea pig hearts exhibit better functional return and reduced [Ca2+]mito, despite enhanced [Ca2+]cyto, during ischemia and REP but show reduced sensitivity to inotropic intervention before or after ischemia compared with young hearts. Although the guinea pigs we used were not specifically bred for aging studies, they nevertheless provide a representative summary of results for comparison against clinical correlates using a nonstandard aging model. Although old and young hearts exhibited significant difference in body and heart weight, even the functional indexes normalized to account for size, like coronary flow and percent infarcted tissue, clearly showed that old hearts were better preserved than young hearts after the same duration of global ischemia and REP in all three groups of studies using different fluorescent markers. Aging-associated protection does not appear to be related to redox state or to [Ca2+]cyto, but it may be linked to a better protection against elevated [Ca2+]mito. Clearly, additional studies are warranted to determine if and how attenuation of [Ca2+]mito loading protects old hearts against I/R injury and to explore differences in contractile protein expression and cross-bridge kinetics by which to evaluate if these mechanisms are better protected after I/R injury in old vs. young hearts. Other studies may be directed to investigate differences, if any, between recovery from global vs. regional I/R injury. Moreover, real-time online measurement of ROS in this model will help to better explore age-related differences in the link between oxidative stress and [Ca2+]mito uptake and recovery during I/R injury.

GRANTS

This research was supported in part by grants from the American Heart Association (AHA) 0735325N to S. S. Rhodes, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) HL-089514, AHA 0855940G, Veterans Affairs Merit 8204-05P to D. F. Stowe, and NHLBI HL-095122 to A. K. S. Camara.

DISCLOSURES

The authors assert no conflict of interest in carrying out this research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Anita Tredeau and Steve Contney for capable assistance with this work.

REFERENCES

- 1. An JZ, Varadarajan SG, Camara AKS, Chen Q, Novalija E, Gross GJ, Stowe DF. Blocking Na+/H+ exchange reduces [Na+]i and [Ca2+]i load after ischemia and improves function in intact hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H2398–H2409, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. An JZ, Varadarajan SG, Novalija E, Stowe DF. Ischemic and anesthetic preconditioning reduces cytosolic [Ca2+] and improves Ca2+ responses in intact hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H1508–H1523, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beckman KB, Ames BN. The free radical theory of aging matures. Physiol Rev 78: 547–81, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bendele AM, Hulman JF. Effects of body weight restriction on the development and progression of spontaneous osteoarthritis in guinea pigs. Arthritis Rheum 34: 1180–1184, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boengler K, Schulz R, Heusch G. Loss of cardioprotection with ageing. Cardiovasc Res 83: 247–261, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brandes R, Maier LS, Bers DM. Regulation of mitochondrial [NADH] by cytosolic [Ca2+] and work in trabeculae from hypertrophic and normal rat hearts. Circ Res 82: 1189–1198, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Camara AK, Lesnefsky EJ, Stowe DF. Potential therapeutic benefits of strategies directed to mitochondria. Antioxid Redox Signal 13: 279–347, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Camara AKS, Chen Q, An JZ, Novalija E, Riess ML, Rhodes SS, Stowe DF. Comparison of hyperkalemic cardioplegia with altered [CaCl2] and [MgCl2] on [Ca2+]i transients and function after warm global ischemia in isolated hearts. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 45: 1–13, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen Q, Camara AKS, An JZ, Riess ML, Novalija E, Stowe DF. Cardiac preconditioning with 4 h, 17°C ischemia reduces [Ca2+]i load and damage in part via KATP channel opening. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H1961–H1969, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen Q, Camara AKS, Rhodes SS, Riess ML, Novalija E, Stowe DF. Cardiotonic drugs differentially alter cytosolic [Ca2+] to left ventricular relationships before and after ischemia in isolated guinea pig hearts. Cardiovasc Res 59: 912–925, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fabiato A, Fabiato F. Calcium-induced release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of skinned cells from adult human, dog, cat, rabbit, rat, and frog hearts and from fetal and new-born rat ventricles. Ann NY Acad Sci 307: 491–522, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ferrara N, Bohm M, Zolk O, O'Gara P, Harding SE. The role of Gi-proteins and beta-adrenoceptors in the age-related decline of contraction in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 29: 439–448, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ferrara N, O'Gara P, Wynne DG, Brown LA, del Monte F, Poole-Wilson PA, Harding SE. Decreased contractile responses to isoproterenol in isolated cardiac myocytes from aging guinea-pigs. J Mol Cell Cardiol 27: 1141–1150, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fitzsimons DP, Patel JR, Moss RL. Aging-dependent depression in the kinetics of force development in rat skinned myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 276: H1511–H1519, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gabel SA, Walker VR, London RE, Steenbergen C, Korach KS, Murphy E. Estrogen receptor beta mediates gender differences in ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol 38: 289–297, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jiang MT, Moffat MP, Narayanan N. Age-related alterations in the phosphorylation of sarcoplasmic reticulum and myofibrillar proteins and diminished contractile response to isoproterenol in intact rat ventricle. Circ Res 72: 102–111, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Josephson IR, Guia A, Stern MD, Lakatta EG. Alterations in properties of L-type Ca channels in aging rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 34: 297–308, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jugdutt BI, Jelani A, Palaniyappan A, Idikio H, Uweira RE, Menon V, Jugdutt CE. Aging-related early changes in markers of ventricular and matrix remodeling after reperfused ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in the canine model: effect of early therapy with an angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker. Circulation 122: 341–351, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kennedy RH, Seifen E. Aging: ouabain-sensitive 86Rb+ uptake rate and responsiveness to digoxin in rat left atrial muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 248: 104–110, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lakatta EG. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises. Part III. Cellular and molecular clues to heart and arterial aging. Circulation 107: 490–497, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises. Part I. Aging arteries: a “set up” for vascular disease. Circulation 107: 139–146, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises. Part II. The aging heart in health: links to heart disease. Circulation 107: 346–354, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lenaz G, D'Aurelio M, Merlo Pich M, Genova ML, Ventura B, Bovina C, Formiggini G, Parenti Castelli G. Mitochondrial bioenergetics in aging. Biochim Biophys Acta 1459: 397–404, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lesnefsky EJ, Gallo DS, Ye J, Whittingham TS, Lust WD. Aging increases ischemia-reperfusion injury in the isolated, buffer-perfused heart. J Lab Clin Med 124: 843–851, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu M, Zhang P, Chen M, Zhang W, Yu L, Yang XC, Fan Q. Aging might increase myocardial ischemia/reperfusion-induced apoptosis in humans and rats. Age 200: 1–12, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miyata H, Silverman HS, Sollott SJ, Lakatta EG, Stern MD, Hansford RG. Measurement of mitochondrial free Ca2+ concentration in living single rat cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 261: H1123–H1134, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nguyen LT, Rebecchi MJ, Moore LC, Glass PSA, Brink PR, Liu L. Attenuation of isoflurane-induced preconditioning and reactive oxygen species production in the senescent rat heart (Abstract). Anesthesia Analgesia 107: 776, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rhodes SS, Ropella KM, Camara AKS, Chen Q, Riess ML, Stowe DF. How inotropic drugs alter dynamic and static indices of cyclic myoplasmic [Ca2+] to contractility relationships in intact hearts. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 42: 539–553, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Riess ML, Camara AK, Chen Q, Novalija E, Rhodes SS, Stowe DF. Altered NADH and improved function by anesthetic and ischemic preconditioning in guinea pig intact hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H53–H60, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Riess ML, Camara AK, Novalija E, Chen Q, Rhodes SS, Stowe DF. Anesthetic preconditioning attenuates mitochondrial Ca2+ overload during ischemia in Guinea pig intact hearts: reversal by 5- hydroxydecanoic acid. Anesth Analg 95: 1540–1546, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Riess ML, Camara AK, Rhodes SS, McCormick J, Jiang MT, Stowe DF. Increasing heart size and age attenuate anesthetic preconditioning in guinea pig isolated hearts. Anesth Analg 101: 1572–1576, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schulman D, Latchman DS, Yellon DM. Effect of aging on the ability of preconditioning to protect rat hearts from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H1630–H1636, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shim YH. Cardioprotection and ageing. Korean J Anesthesiol 58: 223–230, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sniecinski R, Liu H. Reduced efficacy of volatile anesthetic preconditioning with advanced age in isolated rat myocardium. Anesthesiology 100: 589–597, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stowe DF, Varadarajan SG, An JZ, Smart SC. Reduced cytosolic Ca2+ loading and improved cardiac function after cardioplegic cold storage of guinea pig isolated hearts. Circulation 102: 1172–1177, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. van der Velden J, Moorman AF, Stienen GJ. Age-dependent changes in myosin composition correlate with enhanced economy of contraction in guinea-pig hearts. J Physiol 507: 497–510, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Varadarajan SG, An JZ, Novalija E, Smart SC, Stowe DF. Changes in [Na+]i, compartmental [Ca2+], and NADH with dysfunction after global ischemia in intact hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H280–H293, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Varadarajan SG, An JZ, Novalija E, Stowe DF. Sevoflurane before or after ischemia improves contractile and metabolic function while reducing myoplasmic Ca2+ loading in intact hearts. Anesthesiology 96: 125–133, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]