Abstract

We describe an unintentional significant overdose of darunavir in a treatment-experienced adolescent with decreased darunavir susceptibility and prior treatment failure on darunavir therapy. Minimal toxicity and improved virologic suppression observed with an overdose have prompted consideration of the continued use of higher than recommended dose. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluations justified the individualized use of high-dose darunavir, which resulted in virologic suppression, improved CD4 count and resolution of toxicity.

Keywords: Darunavir, Adolescent, Pharmacokinetics, Safety, HIV

CLINICIAN

The patient, a 12-year old African boy with perinatally acquired HIV infection CDC category C3, had been on antiretroviral therapy (ART) since 6 months of age. His history included failure to thrive, bacterial lymphadenitis and skin infection, recurrent bacterial pneumonia, and neutropenia requiring chronic filgrastim therapy. His family reported excellent adherence to ART, and the pharmacy records confirmed consistent refills of all medications.

Due to recurrent virologic failure, ART had been changed five times during early childhood, and included various combinations of reverse transcriptase (RT) inhibitors (didanosine, stavudine, abacavir, zidovudine, lamivudine, nevirapine) and boosted protease inhibitors (PIs) (amprenavir, atazanavir, tipranavir). At 9 years of age he enrolled in the TMC-114 (Tibotec, Inc.) study and was started on lamivudine, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, enfuvirtide, darunavir (TMC-114), and ritonavir. Genotype Trugene® (at 8 years of age) and virtual phenotype Phenosense™ (at study entry) demonstrated resistance to RT inhibitors and minimal to reduced response to PIs with multiple RT (M41L, K65R, 68G, K70R, V75I, 103wt/N, F116Y, V118I, Q151M, Y181C, G190A, T215Y, 215C/Y) and PI (L10I, K20R, L33F, M36I, K43T, M46I, I54V, I62V, L63P, A71V, T74P, V82T, I84V) mutations. Phenosense™ showed decreased susceptibility to darunavir/ritonavir with a 7.4-fold increased IC50 (biological cut off=3.4; clinical cutoff =96.9).

At the time of study entry, viral load (VL) was 397,000 copies/mL and CD4 was 5.4% (122 cells/mm3). The patient reported good medication adherence except to enfuvirtide, and he initially experienced a significant drop in VL to 60 copies/mL after 12 months, and a CD4 rise to 22% (567 cells/mm3) after 18 months of therapy. However, by the end of the study after nearly 3 years on darunavir, his VL had steadily rebounded to 20,000 copies/mL and CD4 had declined to 16.5% (399 cells/mm3).

During the study the patient was receiving initially 300 mg (2×150 mg tablets) darunavir plus 50 mg (0.6 mL of 80 mg/1 mL liquid) ritonavir followed by 375 mg (2×150 mg tablets and 1×75 mg tablet) darunavir plus 100 mg (1×100 mg tablet) ritonavir twice daily. At the age of 11 years the dose was increased to 450 mg (3×150 mg tablets) darunavir plus 100 mg ritonavir (1×100 mg tablet) twice daily. Upon completion of the study, his darunavir/ritonavir supplier was transferred from the hospital-based research pharmacy to the community pharmacy. Three months later, the new pharmacy discovered that since the transfer of prescription they have been dispensing 600 mg darunavir tablets to the patient instead of the prescribed 150 mg tablets. The actual dose of darunavir taken by the patient, therefore, was 1800 mg (four times the prescribed dose) plus 100 mg ritonavir twice daily. The patient was seen in clinic one month after study completion and had a viral load of 10,200 copies/mL and normal routine laboratory results (no CD4 counts performed). The patient had received the 1800 mg darunavir dose twice daily for a total of 14 weeks. Immediately upon discovery of this dispensing error, the family was contacted by the clinician and interviewed about child’s health. There were no reports of significant illnesses or bodily changes. Since the family only had 600 mg tablets in the household, the patient’s darunavir dose was decreased to 1×600mg tablet twice daily.

TDM CONSULTANT

Darunavir has been approved for use in treatment-experienced HIV-infected pediatric patients >6 years old since 2009 and became approved for use in younger children >3 years of age in December 2011.1–3 Darunavir is administered in combination with ritonavir, a first generation PI used as a PK enhancer of darunavir and other PIs through inhibition of the cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) that serves as a main metabolic pathway for darunavir and other PIs. Data on the use of darunavir in children are limited. Darunavir boosted with ritonavir has been studied in combination with other antiretroviral agents in 2 Phase II pediatric trials.3, 4 TMC114-C212, in which 80 antiretroviral treatment-experienced HIV-1-infected pediatric subjects 6 to less than 18 years of age and weighing at least 20 kg were included and TMC114-C228, in which 21 antiretroviral treatment-experienced HIV-1 infected pediatric subjects 3 to less than 6 years of age and weighing at least 10 kg were included.3, 4 Dose recommendations from the two studies were based on similar darunavir plasma exposures in children compared to adults, and similar virologic response rates and safety profile in children compared to adults. In particular, there is paucity of data on the response to therapy with partially sensitive HIV and any therapeutic dose adjustment to meet suggested therapeutic targets in adults. Scaling the darunavir dose to the lowest possible dose available in the patient was driven primarily by safety concerns, though it appears there was no history of significant clinical symptoms reported by the family. Prolonged high exposure to darunavir (substrate of the CYP3A4) with the unchanged booster ritonavir dose could have induced the CYP3A4 metabolism and clearance of the drug and therefore could now create suboptimal exposure with 600 mg darunavir twice daily. Equally, the capacity of darunavir to inhibit CYP34A could have led to the decreased metabolism of the drug and could provide high exposure with the standard of care darunavir dose. I would recommend conducting a pharmacokinetic (PK) evaluation in the patient during the clinic visit when feasible.

CLINICIAN

The patient was seen in clinic five days later. He was asymptomatic, had a normal physical exam with a VL of 72 copies/mL and CD4 of 22% (630 cells/mm3). Other laboratory results were normal except for a mild elevation of fasting total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol (Grade 2 DAIDS Grading of the Pediatric Adverse Events5: 247 mg/dL and 160 mg/dL, respectively). The patient had a therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) sample (single blood draw after unobserved dose with reported time of the intake) with 600 mg darunavir/100 mg ritonavir dose obtained during the visit in clinic.

TDM CONSULTANT

Prolonged exposure to a very high darunavir dose in the case did not produce any significant clinical toxicity except for the mild elevation in lipids. Pediatric darunavir study TMC114-C212 has reported overall low frequency of clinical and laboratory adverse events which included vomiting (13%), diarrhea (11%), abdominal pain (10%), headache (9%), rash (5%), nausea (4%) and fatigue (3%).3, 4 Grade 3 or 4 (DAIDS Grading of the Pediatric Adverse Events)5 laboratory abnormalities included elevated ALT (Grade 3: 3%; Grade 4: 1%) and AST (Grade 3: 1%), increase in pancreatic amylase (Grade 3: 4%, Grade 4: 1%) and lipase (Grade 3: 1%), and increase in total cholesterol (Grade 3: 1%) and LDL (Grade 3: 3%).3, 4 A more recent, smaller pediatric study TMC114-C228 reported similar frequency of clinical adverse events with diarrhea (19%), vomiting (14%) and rash (10%), and no Grade 3 or 4 laboratory abnormalities.3 Since the turnaround time for the TDM result is usually within a few days or a couple of weeks depending on the availability of the assay and the need to shipment, I would recommend continuing 600 mg dose twice daily pending the TDM results. I would even consider empirically increasing the dose to 1200 mg darunavir with 100 mg ritonavir in order to retain high darunavir exposure, which has proved to be beneficial to the virologic suppression, and to decrease the mild lipidemia most likely associated with high darunavir exposure. I would also recommend repeating clinical, laboratory and TDM evaluation in 4 weeks after reaching the steady state with a new dose. When possible multiple sample PK study with an observed dose should be performed.

CLINICIAN

Pending the TDM results, the patient’s dose was increased to 2×600 mg darunavir tablets (1200 mg dose) with 100 mg ritonavir twice daily. The increase of the dose was done based on the lack of toxicity and improved clinical outcome. Four weeks later patient had repeat clinical and TDM evaluations. At this visit, his fasting cholesterol had normalized, while VL continued to be low at 356 copies/mL. During this visit 4 PK samples were obtained: just prior to an observed dose in clinic (12 hours after the previous unobserved dose with reported time of the intake), and 1, 2, and 4 hours after the observed dose.

TDM CONSULTANT

By the time of the second TDM evaluation the results of the first PK study became available. During the first PK evaluation a single blood sample for measurement of darunavir concentration was obtained 8.5 hours after an unobserved dose at home, 5 days after starting the 600 mg dose. Darunavir was measured using a CLIA approved validated HPLC assay developed as a modification of the published assay from PREDIZISTA study.6 The lower limit of quantification was 92 ng/mL. The measured concentration was 3967 ng/mL, and compared to the mean adult steady-state 12-hour trough of >3500 ng/mL,3 the patient’s estimated 12-hour trough was judged likely to be low, especially considering the reduced viral susceptibility to darunavir. The continued use of the higher (1200 mg) darunavir dose therefore appeared to be well justified. The improvement of the lipidemia was most likely due to the decreased darunavir exposure, while the therapeutic success of the increased darunavir dose was preserved maintaining the HIV RNA viral load below 400 copies/mL.

CLINICIAN

After 24 months of high-dose darunavir, including 3 months with triple-dose and 21 months with double-dose darunavir, the patient remains asymptomatic with normal growth and development. No significant changes were made to his antiretroviral regimen except the change of formulation for lamivudine (from 135 mg liquid to 150 mg tablet) and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate dose (from 150 mg to 300 mg) 5 months and 12 months after start of double-dose darunavir, respectively. No new therapeutic agents were introduced into his care. The patient maintains normal lipids, liver enzymes, creatinine, and lipase. His chronic neutropenia resolved and filgrastim was discontinued after 16 months on antiretroviral therapy with 1200 mg darunavir dose. His VL has been continuously <400 copies/mL, and his CD4 count >15% (>350 cells/mm3).

TDM CONSULTANT

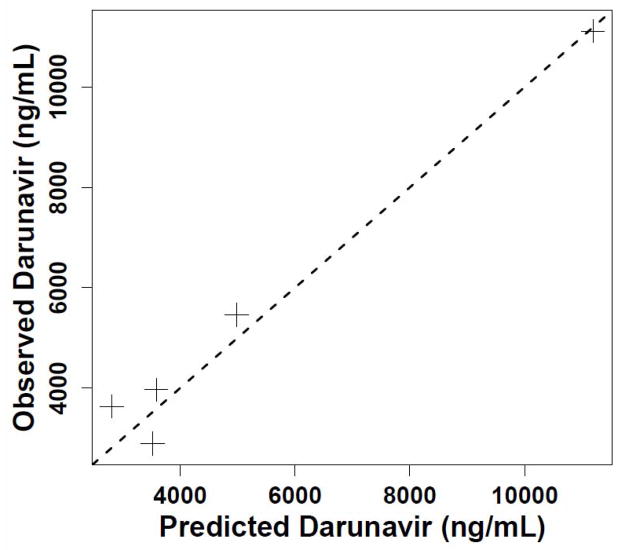

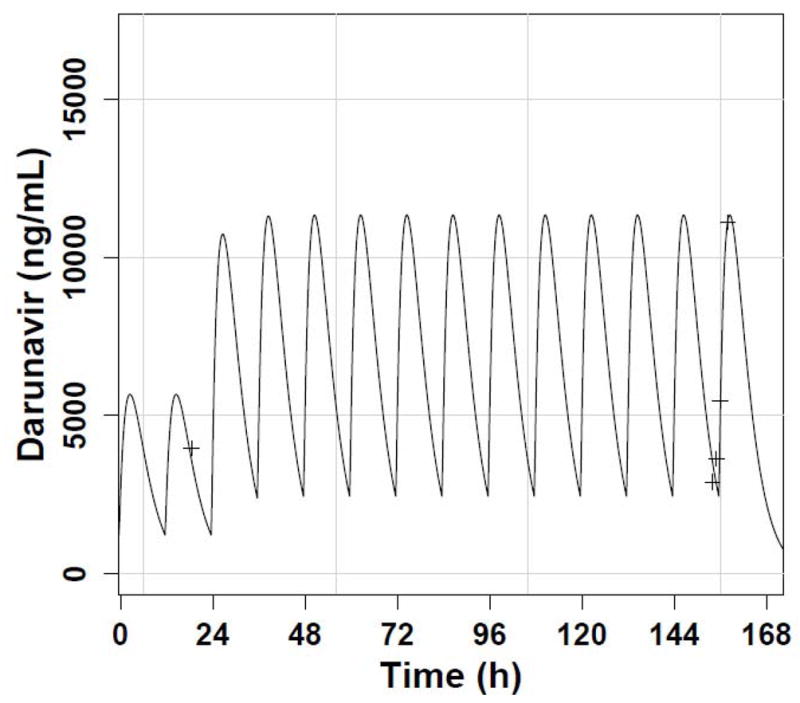

Using the Non-Parametric Adaptive Grid (NPAG) module of the Pmetrics (formerly MM-USCPACK) population modeling package (http://www.lapk.org) for R (http://www.R-project.org), we separately fitted all the patient’s darunavir and ritonavir dosing and concentration data obtained in the clinic, each drug to its own one-compartment model with linear absorption after a delay and clearance. In addition, we requested and obtained the patient’s individual PK summary (not the raw concentration data) from the TMC-114 study (courtesy of Dr. Thomas Kakuda, Tibotec, Inc.). We used a population approach, which can estimate values of PK parameters in one patient just as in a group of subjects,7 because we aimed to fit all the data available from sampling in the clinic. This would not have been possible with a non-compartmental approach, given the sparseness of the samples. Moreover, because we were estimating parameter values in a single individual, it was not possible to estimate standard errors for the PK parameters. A single apparent darunavir clearance estimate of 0.4 L/kg/h (Table 1) fitted all the concentrations with an observed vs. predicted slope of 0.96 and R2 of 0.97 (perfect is 1.0 in both cases), as shown in Figure 1. This apparent clearance was 1.5-fold higher at age 11–12 than it had been at age 9, and 3-fold higher than the mean adult apparent clearance. Pmetrics estimated the AUC0–12 for each darunavir and ritonavir dosing regimen by integration, as also shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic values of darunavir in the patient (chronological order) compared with adult parameters.

| Patient PK | Adult PK3,14 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PK method | Non-compartmental§ | Population§§ | |||

| DRV Dose (mg) | 300 | 1800 | 600 | 1200 | 600 |

| RTV Dose (mg) | 50 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Age (yrs) | 9 | 11 | 12 | 12 | >18 yrs |

| Weight(kg) | 24.2 | 34.0 | 33.7 | 34.7 | >40 kg |

| Height (cm) | 124.5 | 140.6 | 141.5 | 142.1 | N/A |

| DRV AUC0–12 (mg*h/mL) | 43.1 | 129.8 | 43.3 | 86.6 | 61.7 (33.9–106.5)§§§ |

| RTV AUC0–12 (mg*h/mL) | 2.1 | 8.2 | 6.115 | ||

| DRV Ctrough (ng/mL) | 2580 | 3670 | 1223 | 2447 | 3539 (1255–7368) |

| DRV CL/F (L/h/kg) | 0.28 | 0.41 | 0.139a (0.080–0.253) | ||

| DRV GIQcng/mL/3 | 860c | 1223.3c | 407.7c | 815.7c | 2150d |

PK - pharmacokinetics; DRV- darunavir; AUC0–12 – area under concentration-to-time curve; Ctrough – plasma trough concentration; CL/F- clearance; GIQ- genotypic inhibitory quotient.

TMC-114 study intense 12 hour PK data at week 2 was courtesy of Dr. Thomas Kakuda, Tibotec, Inc.

As described in the text

Range of values in parentheses

Assuming weight is 70kg

GIQ (genotypic inhibitory quotient) = Ctrough/number of DRV mutations

Patient GIQ= Ctrough/number of patient DRV mutations (L33F, I54V, I84V=3) from the genotype Trugene® resistance testing obtained prior to the study entry

Adult GIQ reference from the literature 14

Figure 1.

(A) Predicted darunavir time concentration profile with twice daily dosing (solid line) and observed concentrations with 600 mg dosing (smaller peaks) and 1200 mg dosing (higher peaks). The time between sampling events has been compressed for plotting clarity; (B) Observed vs. predicted darunavir concentration plot, with a dashed reference line of slope 1.

Individualized dosing of darunavir that was twice the usual adult dose resulted in improved virologic, immunologic and clinical outcomes in our adolescent patient with decreased susceptibility to darunavir. His tolerance of this high dose of darunavir has been excellent, with an even higher darunavir dose (1800 mg) with unintentional overdose during 14 weeks producing only mild (Grade 2) elevation of cholesterol.

While adolescents are identified as a separate study cohort when investigating the PK and pharmacodynamics (PD) of antiretroviral agents in children, the data on the effect of growth and development on the PK/PD of antiretroviral drugs, and particularly newer agents such a darunavir, are limited.8 Equally limited is our understanding of the developmental changes during pre-puberty and puberty on drug disposition and elimination.9 In our patient we found a significant increase in darunavir apparent clearance between 9 and 12 years of age. This was certainly not explained by a decrease in ritonavir exposure, since his ritonavir dose and AUC0–12 both increased, as shown in Table 1. During this period the patient crossed the Tanner stages from I to II and showed the significant acceleration in his physical growth that typically precedes the onset of puberty. Since puberty is characterized by an increase in growth velocity and significant changes in body composition such as changes distribution of fat and muscular mass, hormonal changes, changes in renal excretion and possible changes in enzymatic capacity of CYP450 system,10–12 it is feasible to speculate that these changes could be responsible for the observed increase in drug elimination rates.

Dosing of darunavir in pediatric patients between 6 and 18 years of age is based on the weight of the patient without consideration of his/her developmental stage. We have shown that premature introduction of lower adult doses can lead to sub-therapeutic concentrations and virologic failure, with the potential for accelerated resistance. The increased darunavir apparent clearance in our case resulted in significant decrease in darunavir exposure between 9 and 12 years of age with the standard darunavir dose. This explains the higher darunavir dose required to reach a trough concentration above the suggested target of 2200 ng/mL for wild-type virus.13 Despite the good virologic response, the genotypic inhibitory quotient (GIQ) with standard and higher doses remained below the suggested threshold of 2150 (Table).14 However, in our patient, a GIQ of 400 was associated with virologic rebound, while >800 was sufficient to maintain suppression. We do acknowledge that the darunavir mutations used in the calculations of GIQ were obtained prior to the study entry. Due to the low VL of HIV at the time obtaining the new genotype study was not practical.

The appropriate dosing of antiretroviral medications in adolescents is complex and depends on multiple factors, including developmental changes throughout puberty. While only a single patient, this report highlights the importance of individualized antiretroviral therapy and a concentration-targeted approach to dosing of antiretroviral drugs in adolescent population. The effect of developmental changes on darunavir PK and the potential need for increased darunavir doses in some children and adolescents need to be more thoroughly evaluated, especially during all phases of drug development.

Acknowledgments

Funding support: The authors were supported by the National Institutes of Health Public Health Service grants from National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease K23AI076106 (MN), National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering R01 EB005803 (MN), National Institute of General Medical Sciences R01 GM068968 (MN), Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development K23 1K23HD060452 (NR), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease U01 AI 68632 (EC) and 1U54HD071600-01 (EC).

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the patient and the family who participated in the clinical pharmacokinetic evaluation and gave us permission to use the clinical and pharmacokinetic data for the case presentation.

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of HIV-Infected Children. [Accessed November 11, 2011.];Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Pediatric HIV Infection. 2011 Aug 11;:1–268. Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/PediatricGuidelines.pdf.

- 2.Neely M, Kovacs A. Managing treatment-experienced pediatric and adolescent HIV patients: role of darunavir. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2009;5(3):595–615. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s4595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [Accessed January 2, 2012.];Prezista - US Package Insert. Available at: http://www.prezista.com.

- 4.Blanche S, Bologna R, Cahn P, Rugina S, Flynn P, Fortuny C, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety and efficacy of darunavir/ritonavir in treatment-experienced children and adolescents. AIDS. 2009;23(15):2005–2013. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328330abaa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Division of AIDS (DAIDS) [Accessed January 2, 2012.];Table for Grading the Severity of Adult and Pediatric Adverse Events. Available at: http://www.niaid.nih.gov/LabsAndResources/resources/DMIDClinRsrch/pages/toxtables.aspx.

- 6.Pellegrin I, Wittkop L, Joubert LM, Neau D, Bollens D, Bonarek M, et al. Virological response to darunavir/ritonavir-based regimens in antiretroviral-experienced patients (PREDIZISTA study) Antivir Ther. 2008;13(2):271–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neely M, Jelliffe R. Practical therapeutic drug management in HIV-infected patients: use of population pharmacokinetic models supplemented by individualized Bayesian dose optimization. J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;48(9):1081–1091. doi: 10.1177/0091270008321789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neely MN, Rakhmanina NY. Pharmacokinetic optimization of antiretroviral therapy in children and adolescents. Clin Pharmacokinet. 50(3):143–189. doi: 10.2165/11539260-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rakhmanina NY, Capparelli EV, van den Anker JN. Personalized therapeutics: HIV treatment in adolescents. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84(6):734–740. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linday LA, Drayer DE, Khan MA, Cicalese C, Reidenberg MM. Pubertal changes in net renal tubular secretion of digoxin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1984;35(4):438–446. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1984.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lambert GH, Schoeller DA, Kotake AN, Flores C, Hay D. The effect of age, gender, and sexual maturation on the caffeine breath test. Dev Pharmacol Ther. 1986;9(6):375–388. doi: 10.1159/000457262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hein K. Developmental pharmacology in adolescence. The inauguration of a new field. J Adolesc Health Care. 1987;8(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(87)90241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sekar V, Vanden Abeele C, Van Baelen B, Vis P, Lavreys L, de Pauw M, et al. Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Analyses of Once-daily Darunavir in the ARTEMIS Study. 9th Intenational Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV Therapy; New Orleans, LA, USA. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez de Requena D, Bonora S, Cometto C, Magnani G, D’Avolio A, Milia M, et al. Effect of Darunavir (DRV) genotypic inhibitory quotient (gIQ) on the virological response to DRV-containing salvage regimens at 24 weeks. 9th Intenational Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV Therapy; New Orleans, LA, USA. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scholler-Gyure M, Kakuda TN, Sekar V, Woodfall B, De Smedt G, Lefebvre E, et al. Pharmacokinetics of darunavir/ritonavir and TMC125 alone and coadministered in HIV-negative volunteers. Antivir Ther. 2007;12(5):789–796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]