Abstract

Objectives

To describe the network of collaboration among agencies that serve children with complex chronic conditions (CCC) and identify gaps in the network.

Methods

We surveyed representatives from agencies that serve children with CCC in Forsyth County, North Carolina about their agencies’ existing and desired collaborations with other agencies in the network. We used Social Network Analytical methods to describe gaps in the network. Mean out- and in-degree centrality (number of collaborative ties extending from or directed towards an agency) and density (ratio of extant ties to all possible ties) were measured.

Results

In this network with 3,658 possible collaborative ties, care-coordination agencies and pediatric practices reported the highest existing collaborations with other agencies (out-degree centrality: 32 and 30 respectively). Pediatric practices reported strong ties with subspecialty clinics (density: 73%), but weak ties with family support services (density: 3%). Pediatric practices and subspecialty clinics (in-degree: 26) received the highest collaborative ties from other agencies. Support services and durable medical equipment companies reported low ties with other agencies (out-degree: 7 and 10 respectively). Nursing agencies reported the highest desired collaborations (out-degree: 18). Support services, pediatric practices and care-coordination programs had the highest in-degree centrality (7, 6 and 6 respectively) for desired collaborations. Nursing agencies and support services had the greatest gaps in collaboration.

Conclusions

Although collaboration exists among agencies serving children with CCC, there are many gaps in the network. Future studies should explore barriers and facilitators to inter-agency collaborations and whether increased collaboration in the network improves patient-level outcomes.

Keywords: children, special needs, collaboration, health services research

INTRODUCTION

Of the estimated 9.3 million children in the United States with special health care needs,1,2 a subgroup of children have greater medical complexity.3 In this paper we use the term children with complex chronic conditions (CCC)4 to describe these children who are also referred to as medically complex children,5 children with medical complexity6 or medically fragile children7. Children with CCC are living longer because of advances in technology8 and account for substantial health-care utilization among children.7,9–11 These children receive care from multiple medical, educational and social service providers through various agencies for a prolonged period of time.

Developing systems of coordinated care for children with special needs in communities is a Healthy People 2020 Objective. 12 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), in a recent White Paper, described the concept of a "medical neighborhood” consisting of the patient’s medical home, specialists and community agencies. 13 The AHRQ recommends a high-functioning medical neighborhood to be critical to our health-care system. Very little information exists on how agencies within the medical neighborhood of children with CCC collaborate with one another to provide care for this population.

We used a novel methodology called Social Network Analysis (SNA) to study the collaborative relationships that exist among agencies that serve children with CCC. SNA methodology has long been used to study relationships between organizations,14–16 but only recently has been applied to health services research.17 Especially when it comes to understanding complex relationships that exist within the medical neighborhood of children with CCC, SNA adds considerable value over traditional approaches that consider only the individual parts of the system. 14,15 The objectives of this study are to describe existing collaboration between agencies that constitute the medical neighborhood of children with CCC and identify “gaps” in the network.

METHODS

The Institutional Review Board of Wake Forest University Health Sciences approved this study. This study was conducted in Forsyth County located in central North Carolina. In 2010, the population of Forsyth County was 350,670.18 Winston-Salem is the largest city in Forsyth County accounting for two thirds of its population. Racial and ethnic minorities constitute 38% of the population of Forsyth County. There are 2 major hospital systems in Forsyth County. The community’s children’s hospital (Brenner Children’s Hospital) is part of the Wake Forest Health System.

Network Specification

The first step in SNA methodology is to identify all members of a network or potential actors. In this case agencies serving children with CCC in Forsyth County are the actors. We defined children with complex chronic conditions as children who are medically fragile, dependent on technology, or have a life-limiting condition. We defined agency as community agencies; pediatric practices; and departments, clinics and special programs within an organization. We generated a preliminary list of agencies in Forsyth County that serve children with CCC from: (1) existing community resource guides, (2) membership rosters of 2 community coalitions, (3) a resource list prepared by the State Title V Agency, and (4) a list of individual and interdisciplinary clinics in the community’s children’s hospital.

Next, we conducted a focus group with members of a community coalition. Coalition members are representatives of agencies serving children with CCC. Ten out of 18 members participated in the focus group facilitated by one of the authors (SG), who is an experienced focus group moderator. Based on the participants’ recommendations, agencies were added to and removed from the preliminary list. Third, an interviewer experienced in qualitative methods (SG) interviewed 8 social workers in the academic medical center and 2 social workers in the community about their knowledge of local agencies. Agencies in the list were added and removed as a result of these interviews. Finally, the research team restricted the study to agencies that meet all the three of the following criteria:

Serve all of Forsyth County

-

Focus on children with CCC and/or their families, defined by:

Agency has special services in place for children with CCC or tailors services for them, or

Agency specifically addresses children with CCC as part of their programmatic goals, or

Children with CCC make up a large portion of the agency’s clientele (10% or more)

Provide ongoing care to children with CCC and/or their families.

As have other researchers, we treated different programs within a large organization as separate agencies if the programs provided a distinct set of services using non-overlapping staff. 15,19 For example, different subspecialty clinics within the local children’s hospital were treated as distinct agencies. However when a subspecialty clinic had multiple programs for children with CCC under the same administrative structure, we grouped those programs together into one entity. All primary care pediatric practices in Forsyth County were included except the pediatric residents’ clinic that is part of the children’s hospital. The final list included 63 agencies (Appendix).

Identification of Key Informants

The study participants were key informants (agency representatives) in the agencies. We contacted each of the agencies to identify appropriate key informants. For each agency, we identified 2 types of key informants: Key Informant A was defined as the person who knows the most about the agency - typically the lead physician in the case of a medical practice or clinic, or the director in the case of a program. Key Informant B was defined as the person in the agency who collaborates the most with other agencies or departments. All agencies had at least one Key Informant A. In 35 agencies, Key Informants A and B were the same. In some agencies, there were multiple Key Informant A or B. If an agency had more than 3 key informants, only 3 were included. We identified 96 key informants representing 63 agencies.

Survey

We conducted a survey of all key informants in October 2010 using Network Genie, an online data-collection tool developed specifically for social network data.20 The link to the survey was emailed to participants. A reminder was sent to non-responders 2 weeks after the first survey. A second reminder was sent to non-responders 5 weeks after the first reminder. Participants received $25 incentives for participating in the study.

The survey had one general question inquiring about collaboration with other agencies followed by 4 follow-up questions about the nature of the relationships that did exist (serving as a resource, receiving resource, making referrals and receiving referrals). “Resource” was defined as care-related information or advice or consultation on how to serve a client or family. We also inquired about agencies’ interest in collaborating with other agencies in the future. Agency-level information obtained included: agency type, duration of existence, number of children served each week, number of staff members in the agency providing direct care to children, and the proportion of children with CCC served by the agency.

Multiple Respondents

Some agencies had multiple respondents (key informants). In determining whether the agency had collaborative relationships, we concluded that a relationship was in place if any informant reported it. This strategy is similar to that used previously by others.15 For questions about duration of existence, number of staff, number of children served and proportion of clientele that are children with CCC, we chose the median value among the multiple respondents.

Agency Attributes

Agencies in the network (Appendix) were classified into 7 types as follows: 28 (44%) subspecialty clinics of the children’s hospital, 7 (11%) nursing agencies, 3 (5%) Durable Medical Equipment (DME) companies, 6 (10%) educational programs, 5 (8%) care coordination programs, 4 (6%) family support services, and 10 (16%) primary-care pediatric practices. Nursing agencies included 4 agencies that provide skilled or private-duty nursing, one long-term care facility and one hospice agency.

Other agency attributes were categorized as follows: type of funding (private non-profit, private for-profit and public); duration of existence (≤ 10 or ≥11 years); number of staff (≤ 20 and ≥21); number of children served in a week (≤50 or ≥51); and proportion of clientele that are children with CCC (≤ 10 and ≥ 11).

Network Variables

For the current study, we used 2 network questions, one that inquired about existing collaboration and the second that inquired about desired collaboration. For existing collaboration, we asked:

“In the past year, with which of the following agencies has your agency collaborated in providing services for children with complex chronic conditions? By collaboration, we mean any relationship that involves exchanging information, sharing resources, and/or coordinating services for the benefit of children with complex chronic conditions.”

For desired collaborations, we asked:

“With which of these agencies would you like to collaborate more in order to effectively provide services for children with complex chronic conditions?”

Respondents were provided a list of all the actors in the network from which to select their responses to these questions.

Network Data

We created network matrices (63×63) for each of the two network questions. Presence of a relationship was coded as ‘1’ and absence of relationship as ‘0’. To calculate network measures between and within the agency types, we partitioned (blocked) the 2 network matrices by the agency types and created 7×7 block matrices. In order to measure only desired additional collaborations, for the second network question, we deleted any existing relationships identified by agencies in the first question.

Network Description and Network Measures

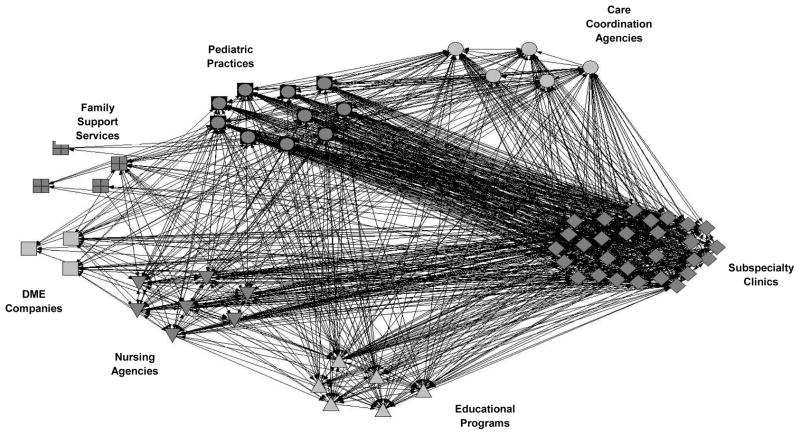

We constructed a visual representation of the existing collaboration network (Figure 1).17 The agencies (actors) are depicted in different shapes. The connection from an actor to other actors in the network is called the arc (represented as arrows). The direction of the arrows represents the direction of the collaboration. A tie is any relationship between actors in the network – either to or from an actor to other actors in the network. In other words, arcs represent the relationship between 2 actors and the direction of the relationship, but ties represent any relationship irrespective of the direction of the relationship.

Figure 1.

Existing Collaborations between Agencies Serving Children with Complex Chronic Conditions

We calculated the mean out-degree centrality and in-degree centrality for the 7 agency types. Out-degree centrality is the connectivity of an actor within the network measured by the number of reported arcs from an actor to other actors in the network. In-degree centrality is the number of arcs to the actor from other actors in the network. Degree centrality is expressed as a whole number and could range from 0 (no collaboration) to 62 (collaboration with all other agencies in the network).

We used density to measure the strength of collaborations in the network as a whole, and between and within the 7 agency types. Density is the proportion of actual ties between actors to the total number of possible ties. Density ranges from 0% to 100%. A higher density indicates greater relationship. Density of existing collaboration was the proportion of existing collaborations to all possible collaborations in the network. Density of desired collaboration was the proportion of desired collaborations to collaborations that are possible but do not currently exist. We defined “ideal” collaborations as the sum of existing collaborative ties and desired collaborative ties. We computed “gap” scores as the percentage of the ideal collaborative ties that do not currently exist.

Data Analysis

For description of agency attributes, we used Stata Intercooled Version 10. We used UCINET 6, statistical software specifically designed to analyze SNA data, for descriptive statistics network analysis. 21 We calculated summary statistics for the whole network and the blocked matrices. We used the NetDraw option for visual representation of the data.

RESULTS

Of the 96 eligible participants, 80 (83%) responded to the survey. Seventy-seven (80%) completed the entire survey. Of the 63 agencies, we received responses from at least one key informant in 59 agencies (94%). Agencies that did not respond include one each of subspecialty clinics, pediatric practices, DME companies and educational programs.

Agency Characteristics

Of the agencies in the network, 18 (28%) were private for-profit, 35 (56%) were private nonprofit and 10 (16%) were government agencies. A majority of the agencies existed for ≥ 11 years (76%), had ≤ 20 staff (75%), served ≤ 50 children a week (53%) and had ≥ 11% CCC clientele (59%).

Existing Collaborations

In the existing collaboration network (Figure 1), the actors (agencies) are represented as different shapes, and grouped into 7 categories based on the types of services they provide. This allows a more direct inspection of how much the agencies collaborate with others of the same type, as well as across type.

One of the first patterns to note in Figure 1 is that this network is characterized by relatively high levels of collaboration. With 63 agencies in the network, there are a total of 3906 (63×62) possible ties where collaboration might occur. Because we were unable to collect data from representatives of 4 of the agencies, we could not assess a subset of these ties, 248 to be exact. Of the 3658 ties where collaboration could be assessed, the respondents reported 1380 collaborative relationships, or 38% of the possible ties. This percentage corresponds to the density of the network.

Again referring to Figure 1, some portions of the network are denser than others. For example, the connections between pediatric practices and subspecialty clinics are especially dense, implying that primary care and specialty care are highly linked in this community. There is also strong collaboration among the various specialty clinics. Also, whereas pediatric practices are highly linked to specialty clinics, there is relatively weak collaboration between pediatric practices and either support services or DME companies. Likewise, collaborative ties to and from DME companies and nursing agencies are very sparse.

The centrality measures in Table 1 provide a quantitative assessment of the degree to which the different agencies are connected to the rest of the network. Out-degree centrality reflects each agency’s own report of how much they collaborate with others, while in-degree centrality reflects other agencies’ reports of collaboration. Care coordination agencies and pediatric practices had the highest mean out-degree centrality (32.0 and 30.3 respectively), meaning that they identified the most numbers of agencies in the network as collaborators. Family support services had the least out-degree collaboration (mean out-degree centrality: 6.8). Pediatric practices (26.1), subspecialty clinics (25.5) and schools (21.3) were the 3 agency types to have the highest mean in-degree centrality meaning that they were most often identified by other agencies as collaborators. Family support services had the least in-degree centrality (5.3).

Table 1.

Existing and Desired Collaborations between Agencies (Mean Out-Degree and In-Degree Centrality*)

| Existing Collaborations | Desired Additional Collaborations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Out-Degree | In-Degree | Out-Degree | In-Degree | |

| Pediatric Practices | 30.3 | 26.1 | 1.3 | 6.1 |

| Subspecialty clinics | 24.4 | 25.5 | 2.9 | 3.4 |

| Care-Coordination Programs | 32.0 | 18.6 | 3.8 | 5.6 |

| Nursing Agencies | 18.9 | 17.6 | 18.0 | 3.1 |

| DME Companies | 10.0 | 13.0 | 1.0 | 1.3 |

| Educational Programs | 21.6 | 21.3 | 1.0 | 5.2 |

| Support Services | 6.8 | 5.3 | 6.5 | 6.5 |

Out-degree centrality is the number of reported arcs from an actor to other actors in the network. In-degree centrality is the number of arcs to the actor from other actors in the network.

We next considered the degree of collaboration between and within the 7 agency types, defined by the respective density measure. These density measures are shown in Table 2. In line with the pattern previously noted in Figure 1, pediatric practices have high collaborations with subspecialty clinics (73%). However, their collaborations with DME companies (26%) and support services (3%) are low. Subspecialty clinics have good collaborations with pediatric practices (61%), but their collaborations with other subspecialists is lower (47%). Care coordination programs reported better collaborations than other agency types. They have high collaboration with pediatric practices (68%), schools (53%) and, nursing agencies (60%), but they are not well connected to DME companies (27%) or support services (20%). Nursing agencies are not well connected to other agency types (density ranged from 4% to 39%). Although educational programs are connected with other educational agencies, they are not connected well with other agency types. Family support services (8% to 21%) and DME companies (0% to 29%) have the lowest connection with other agencies types.

Table 2.

Density of Existing Collaborations between Agencies Serving Children with CCC

| Pediatric Practices | Subspecialty Clinics | Care Coordination Programs | Nursing Agencies | DME Companies | Educational Programs | Family Support Services | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatric Practices | 11% | 73% | 44% | 38% | 26% | 50% | 3% |

| Subspecialty Clinics | 61% | 47% | 25% | 26% | 20% | 28% | 9% |

| Care Coordination Programs | 68% | 49% | 60% | 60% | 27% | 53% | 20% |

| Nursing Agencies | 39% | 32% | 31% | 19% | 38% | 33% | 4% |

| DME Companies | 25% | 13% | 20% | 29% | 0% | 17% | 0% |

| Educational Programs | 32% | 33% | 40% | 31% | 20% | 76% | 15% |

| Family Support Services | 10% | 5% | 20% | 18% | 8% | 21% | 17% |

Gaps in the Network

The first set of analysis indicated that collaborative relationships exist for 38% of the possible ties, with much more collaboration occurring in some segments of the network than in others. This result raises the question of what the network should look like. The network studied here has a relatively high density score, but should it be even higher? To what extent are key collaborative relationships missing? To answer these questions, the survey asked respondents to indicate which agencies they desired to collaborate with. These data allowed us to identify the agencies’ own view of where there are gaps in the network.

The data on current collaboration indicated that collaboration did not exist for 2278 of the 3658 possible ties. The data on desired collaboration showed that agencies wanted to collaborate in 268 (12%) of the 2278 “unactualized” ties.

To identify where in the network new collaboration is most desired, we computed a second set of out-degree and in-degree centrality measures for each type of agency (Table 1). Nursing agencies had the highest desired out-degree centrality score (mean: 18.0), signifying the greatest desire to form new collaborations. Conversely, pediatric practices, educational programs and DME companies had the lowest desired out-degree centrality (1.3, 1.0, and 1.0 respectively), indicating little desire for additional collaborations. In-degree centrality scores indicate the degree to which other agencies desire to collaborate with a particular agency. Family support services (6.5), pediatric practices (6.1) and care coordination programs (5.6) were the agency types with which other agencies desired to collaborate.

To further characterize desired collaborative ties between and within agency types, we calculated density measures of desired additional collaborations (Table 3). Pediatric practices desired to collaborate with care coordination programs (20%) and support services (17%). Subspecialty clinics desired additional collaborations with pediatric practices (26%) and educational programs (14%). Interestingly, care coordination programs were interested in collaborating with other care coordination programs (50%). Nursing agencies had the highest desired collaboration of all agency types, ranging from 23% to 58%. Family support services desired to have additional collaborations with pediatric practices (25%). Other than nursing agencies, there was very little desire for agencies to collaborate with DME companies.

Table 3.

Desired Additional Collaborations between Agencies Serving Children with CCC

| Pediatric Practices | Subspecialty Clinics | Care Coordination Programs | Nursing Agencies | DME Companies | Educational Programs | Family Support Services | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatric Practices | 0% | 0% | 20% | 3% | 0% | 0% | 17% |

| Subspecialty Clinics | 26% | 3% | 10% | 6% | 2% | 14% | 6% |

| Care Coordination Programs | 0% | 15% | 50% | 14% | 0% | 7% | 6% |

| Nursing Agencies | 58% | 46% | 33% | 26% | 23% | 39% | 33% |

| DME Companies | 0% | 4% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Educational Programs | 0% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 17% | 18% |

| Family Support Services | 25% | 10% | 6% | 9% | 0% | 11% | 10% |

Finally, we measured “gaps” in the network, defined as instances where two agencies did not currently collaborate but desired to collaborate (Table 4). Nursing agencies had the greatest gaps in collaboration in the network ranging from 27% with DME companies to 89% with support services. Family support services reported no gaps in collaboration with DME companies (0%), but reported gaps in collaboration with all other agency types (29% to 69%). Most agency types in the network perceived gaps in collaboration with care coordination agencies and support services.

Table 4.

Gaps* in the Collaboration Network of Agencies Serving Children with CCC

| Pediatric Practices | Subspecialty Clinics | Care Coordination Programs | Nursing Agencies | DME Companies | Educational Programs | Family Support Services | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatric Practices | 0 % | 0 % | 20 % | 4 % | 0 % | 0 % | 86 % |

| Subspecialty Clinics | 14 % | 3 % | 23 % | 14 % | 6 % | 26 % | 38 % |

| Care Coordination Programs | 0 % | 14 % | 25 % | 9 % | 0 % | 6 % | 20 % |

| Nursing Agencies | 48 % | 49 % | 42 % | 53 % | 27 % | 44 % | 90 % |

| DME Companies | 0 % | 22 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % |

| Educational Programs | 0 % | 2 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 5 % | 50 % |

| Family Support Services | 69 % | 65 % | 20 % | 29 % | 0 % | 29 % | 33 % |

desired ties/sum of existing and desired ties

Gap ≥ 31%

Gap ≥ 31%

Gap 16 to 30%

Gap 16 to 30%

Gap ≤ 15%

Gap ≤ 15%

DISCUSSION

In this descriptive study of the medical neighborhood of children with CCC, we found that while a considerable amount of collaboration exists among agencies, there are many gaps in this collaboration network, especially between clinical programs and community programs such as nursing agencies and family support services. To quantify collaboration, we used social network analysis (SNA), a method that has, to our knowledge, not been used previously in health services research in studying the system of care for children with CCC.

To serve as a medical home for children with CCC, primary-care pediatric practices should function as a hub and collaborate with all other agencies serving children with CCC.22 According to the 2001 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs, while 54% of caregivers reported that their child’s physicians communicated with one another, only 37% said that these physicians communicated with other providers or agencies. 1 Our study shows that pediatric practices have high collaborative relationships to and from other agencies. However, these collaborations are primarily with subspecialty clinics, schools and with care-coordination agencies. Gupta et al. surveyed pediatricians and found that only 23% reported that someone in their practice contacts school to about child’s health needs.23 Our study shows better collaborative relationships of pediatricians with schools, but poor ties with other community-based programs such as family support services, nursing agencies and DME companies that are critical to the care of children with CCC. Future studies should evaluate whether improving pediatric practices’ collaborations with community-based agencies will improve receipt of support services for children with CCC.

Subspecialty clinics have good connections with other agencies, but their primary connections are with pediatric practices and other subspecialists. Stille et al, in a survey of parents, found that 38% of parents served as an intermediary in communication between primary-care physicians and specialist physicians. 24 As children with CCC receive care from multiple subspecialists, it is important for subspecialists to collaborate with one another in the care of children with CCC. However, in the region we studied, collaboration among subspecialists is moderate at best, and subspecialty clinics did not express a desire to connect with other agencies except pediatric practices.

We found that care coordination agencies identified many agencies in the network as their collaborators but were less likely to be identified as a collaborator by other agencies. The discrepancy might result from the indirect role that coordination agencies have and the relative lack of direct interaction with patients and families. Pediatric practices and nursing agencies indicated a desire for more collaboration with care-coordination agencies; if realized, these collaborations could improve care of children with CCC.

Nursing agencies and DME companies are important providers of care for children with CCC. It is concerning that there are gaps in connections between these community-based agencies and other agencies in the network. Of all agency types, nursing agencies have the largest gaps in collaboration. Nursing agencies also have high desire to connect with other agencies in the network especially with pediatric practices. Interventions should be developed that connect nursing agencies and DME companies to other agencies.

Our study has programmatic, policy and research implications. The low level of collaboration that we observed between pediatric practices and community programs might be addressed by efforts to familiarize pediatricians with those community programs that serve their patients. To this end, we have arranged for community agencies to staff an informational booth at an upcoming Continuing Medical Education event for primary care physicians in our region. Data from studies such as this study could be used to inform policy to improve care of children with CCC by directing resources specifically toward agencies that have the greatest gaps in collaboration. We observed significant variation in the collaborative ties across agencies that serve children, implying a potential for increasing such ties and a need for research on interventions that foster inter-agency collaboration, such as benchmarking and financial incentives. Existing variation in the extent of collaboration also provides an opportunity for observational studies of whether greater collaboration is associated with improved patient outcomes.

Our study demonstrates the usefulness of SNA to study and enhance pediatric systems of care. Although the use of SNA in pediatric studies is limited, SNA has been used to study the influence of social networks on adolescent health behavior, 25 to evaluate community programs for children at risk of violence 26 and to study collaboration among agencies working to prevent child abuse.27 Luke et al describe the study of organizational networks (study of health systems) as one of the three major applications of SNA in public health.28 SNA is a particularly useful tool for health services researchers interested in gaining insight into and evaluating systems of care for children.

Limitations

Our study is limited to a single county in North Carolina and hence the results may not be generalizable to the medical neighborhoods for children with CCC in other regions. Hence, our study needs to be replicated in other communities. Although we used multiple approaches to identify agencies in the network we studied, we may not have identified all agencies. On the other hand, the response rate was high among the agencies we surveyed, minimizing selection bias. Another possible limitation is that we relied on agencies’ self-reporting of collaborative relationships. Family perspective on collaboration between agencies could further help identify gaps in the network. Since we used collaborative relationship as a categorical variable (presence/absence of a relationship), we were not able to describe the extent or the quality of collaborations. It is possible that the number of ties is less predictive of patient outcomes than is the quality of the ties. Studies are needed to assess the optimal level of collaboration and the quality of collaborations. Finally, the measure we used to evaluate gaps in collaboration has not been previously validated.

CONCLUSIONS

We have mapped the agencies in the medical neighborhood of children with CCC and have identified gaps in collaboration in this network. Future studies should investigate barriers and facilitators of inter-agency collaborations and whether increased collaboration in the network improves patient-level outcomes.

What’s New.

This study describes existing and desired collaborations between agencies serving children with complex conditions. There are many gaps in this collaboration network, especially between clinical programs and community programs such as nursing agencies and family support services.

Abbreviations

- CCC

Complex Chronic Conditions

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- SNA

Social Network Analysis

- DME

Durable Medical Equipment

Appendix: Agency List

-

Primary-Care Pediatric Practices

Ford Simpson Lively Rice Pediatrics

Forsyth Pediatrics at Kernersville

Forsyth Pediatrics at Robinhood

Forsyth Pediatrics at Westgate

Kernersville Pediatrics

Twin City Pediatrics

Westgate Pediatrics

Winston East Pediatrics

Winston-Salem Health Care

Winston-Salem Pediatrics

-

Subspecialty Clinics (Brenner Children’s Hospital)

Cancer Survivor Clinic

Cleft Lip and Palate Clinic

Cystic Fibrosis Clinic

Developmental Pediatrics Clinic

Genetics Clinic

Hemophilia Clinic

HIV Clinic

Kids Eat Program (a multidisciplinary program for children with feeding disorders)

Muscular Disorders Clinic

Pediatric Cardiology Clinic

Pediatric Endocrinology Clinic

Pediatric Ear, Nose and Throat Clinic

Pediatric Gastroenterology Clinic

Pediatric Motility Disorders Clinic

Pediatric Nephrology Clinic

Pediatric Neurology Clinic

Pediatric Neurosurgery Clinic

Pediatric Oncology Clinic

Pediatric Ophthalmology Clinic

Pediatric Orthopedic Clinic

Pediatric Pulmonology Clinic

Pediatric Rheumatology Clinic

Pediatric Surgery Clinic

Pediatric Urology Clinic

Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery Clinic

Sickle Cell Clinic

Spasticity Clinic

Special Infant Care Clinic (a multidisciplinary clinic for premature infants)

-

Care Coordination Agencies

Community Alternatives Program – Children (Medicaid waiver program for medically fragile children in North Carolina)

Community Alternatives Program – Mental Retardation/Developmental Delay (Medicaid waiver program for children with mental retardation and developmental disabilities in North Carolina)

Child Development Service Agency (Early Intervention Services Program)

Northwest Community Care Network of North Carolina (Medicaid Managed Care Network)

Pediatric Palliative Care Program at Brenner Children’s Hospital

-

Nursing Agencies

Bayada Nurses (Home Health Agency)

Coram Inc. (Home Health Agency)

Maxim Health Care (Home Health Agency)

Metro Nursing (Home Health Agency)

Hospice & Palliative CareCenter

Horizons Residential Care

Pediatric Services of America (Home Health Agency)

-

Durable Medical Equipment Companies

Hometown Oxygen

Pediatric Specialists

United Seating and Mobility

-

Educational Programs

Exceptional Children’s Division of Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools (K-12 educational program for children with special needs)

Governor Morehead Preschool (a school for children with blindness)

Homebound Services of Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools (an educational program for children who are home bound)

Preschool Team of Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools (preschool program for children with special needs)

The Children’s Center for the Physically Disabled (a special school for children with disabilities)

The Special Children’s School (a special school for children with disabilities)

-

Family Support Services

Cancer Services, Inc. (family support for children and families with cancer)

Family Support Network of Greater Forsyth (family support agency for children with special needs)

Mended Little Hearts (family support for children and families with heart diseases)

Piedmont Health Services & Sickle Cell Agency (family support for children with sickle cell disease and hemophilia)

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Nageswaran, Ms. Golden, Dr. O’Shea, Dr. Easterling and Dr. Ip received salary support from the NIH for this project (R21HD061793; PI: Nageswaran). A part of this paper was presented in a poster session at the Annual Pediatric Academic Societies’ Meeting held at Denver, Colorado in May 2011.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McPherson M, Weissman G, Strickland BB, van Dyck PC, Blumberg SJ, Newacheck PW. Implementing community-based systems of services for children and youths with special health care needs: how well are we doing? Pediatrics. 2004 May;113(5 Suppl):1538–1544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. [Accessed 07/05/06];National Survey of Children’s Health, Data Resource Center on Child and Adolescent Health website. 2005 www.nschdata.org.

- 3.Kuo DZ, Cohen E, Agrawal R, Berry JG, Casey PH. A national profile of caregiver challenges among more medically complex children with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011 Nov;165(11):1020–1026. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington State, 1980–1997. Pediatrics. 2000 Jul;106(1 Pt 2):205–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srivastava R, Stone BL, Murphy NA. Hospitalist care of the medically complex child. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005 Aug;52(4):1165–1187. x. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, et al. Children with medical complexity: An emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics. 2011 Mar;127(3):529–538. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buescher PA, Whitmire JT, Brunssen S, Kluttz-Hile CE. Children who are medically fragile in North Carolina: using Medicaid data to estimate prevalence and medical care costs in 2004. Matern Child Health J. 2006 Sep;10(5):461–466. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feudtner C, Hays RM, Haynes G, Geyer JR, Neff JM, Koepsell TD. Deaths attributed to pediatric complex chronic conditions: national trends and implications for supportive care services. Pediatrics. 2001 Jun;107(6):E99. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.e99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA. 2011 Feb 16;305(7):682–690. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010 Oct;126(4):647–655. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neff JM, Sharp VL, Muldoon J, Graham J, Myers K. Profile of medical charges for children by health status group and severity level in a Washington State Health Plan. Health Serv Res. 2004 Feb;39(1):73–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00216.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. [Accessed 6/2/2011];Healthy People 2020 Objectives. http://healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/default.aspx.

- 13.Taylor E, Lake T, Nysenbaum J, Peterson G, Myers D. AHRQ Publication No 11-0064. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Jun, 2011. [Accessed 12/1/2011]. Coordinated Care in the Medical Neighborhood: Critical Components and Available Mechanisms. White Paper (Prepared by Mathematica Policy Research under Contract No. HHSA290200900019I TO2) http://pcmh.ahrq.gov/portal/server.pt/community/pcmh__home/1483/pcmh_home_v2. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott J, Tallia A, Crosson JC, et al. Social network analysis as an analytic tool for interaction patterns in primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2005 Sep-Oct;3(5):443–448. doi: 10.1370/afm.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwait J, Valente TW, Celentano DD. Interorganizational relationships among HIV/AIDS service organizations in Baltimore: a network analysis. J Urban Health. 2001 Sep;78(3):468–487. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, Cleary PD, Marsden PV. Factors affecting influential discussions among physicians: a social network analysis of a primary care practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Jun;22(6):794–798. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0190-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luke DA, Harris JK. Network analysis in public health: history, methods, and applications. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:69–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S. Census Bureau: State and County QuickFacts. Data derived from Population Estimates, American Community Survey, Census of Population and Housing, State and County Housing Unit Estimates, County Business Patterns, Nonemployer Statistics, Economic Census, Survey of Business Owners, Building Permits, Consolidated Federal Funds Report. [Accessed 2/8/2012]; http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/37000.html.

- 19.Friedman SR, Reynolds J, Quan MA, Call S, Crusto CA, Kaufman JS. Measuring changes in interagency collaboration: an examination of the Bridgeport Safe Start Initiative. Eval Program Plann. 2007 Aug;30(3):294–306. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Network Genie. 2011 https://secure.networkgenie.com/

- 21. [Accessed August 25th, 2008];UCINET 6: Social Network Software. 2008 http://www.analytictech.com/ucinet/ucinet.htm.

- 22.Care coordination in the medical home: Integrating health and related systems of care for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2005 Nov;116(5):1238–1244. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta VB, O’Connor KG, Quezada-Gomez C. Care coordination services in pediatric practices. Pediatrics. 2004 May;113(5 Suppl):1517–1521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stille CJ, Primack WA, McLaughlin TJ, Wasserman RC. Parents as information intermediaries between primary care and specialty physicians. Pediatrics. 2007 Dec;120(6):1238–1246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mundt MP. The impact of peer social networks on adolescent alcohol use initiation. Academic pediatrics. 2011 Sep-Oct;11(5):414–421. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedman SR, Reynolds J, Quan MA, Call S, Crusto CA, Kaufman JS. Measuring changes in interagency collaboration: an examination of the Bridgeport Safe Start Initiative. Evaluation and program planning. 2007 Aug;30(3):294–306. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mulroy EA. Building a neighborhood network: interorganizational collaboration to prevent child abuse and neglect. Soc Work. 1997 May;42(3):255–264. doi: 10.1093/sw/42.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luke DA, Harris JK. Network analysis in public health: history, methods, and applications. Annual review of public health. 2007;28:69–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]