Abstract

USG has been used for the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. Scarring and incomplete decompression are the main causes for persistence or recurrence of symptoms. We performed a retrospective study to assess the role of ultrasound in failed carpal tunnel decompression. Of 422 USG studies of the wrist performed at our center over the last 5 years, 14 were for failed carpal tunnel decompression. Scarring was noted in three patients, incomplete decompression in two patients, synovitis in one patient, and an anomalous muscle belly in one patient. No abnormality was detected in seven patients. We present a pictorial review of USG findings in failed carpal tunnel decompression.

Keywords: Carpal tunnel decompression, failed, ultrasound

Introduction

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is the most common peripheral entrapment neuropathy, with an incidence of 0.1%-1%.[1–3] Surgical carpal tunnel decompression is quite effective and remains the preferred modality of treatment in the management of symptomatic carpal tunnel syndrome.[4] The recurrence rate following surgical carpal tunnel decompression varies from 0% to 19%.[5]

The causes of recurrence include fibrosis, tenosynovitis, and incomplete release of the flexor retinaculum.[5–8] Accessory muscle belly and tumor have also been reported as causes of recurrent CTS.[7,9]

A thorough clinical examination should be performed to look for any synchronous pathologies or mimics.[6,10] Imaging of the wrist enables analysis of the wrist for possible causes of recurrence. Various modalities have been used to diagnose recurrence, including USG, electromyography and MRI.[11,12] USG has become the first-line investigation for failed carpal tunnel decompression.[13–15] It is a dynamic, cost-effective, and simple way to assess the carpal tunnel [Figure 1]. We present a pictorial review of the sonographic appearances in cases of failed carpal tunnel decompression.

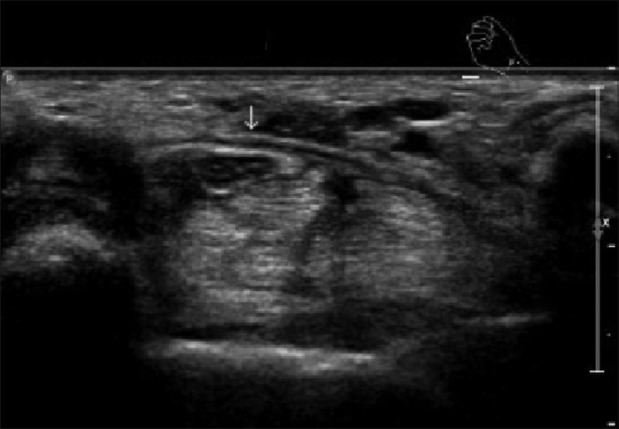

Figure 1.

A 44-year-old female with symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome. Transverse USG shows the transverse carpal ligament (arrow) superficial to a normal median nerve

Materials and Methods

We had 14 patients, of 422 USGs of the wrist performed over the last 5 years, who came with recurrence of carpal tunnel syndrome. The mean age of this cohort was 54 years (range: 35-81 years) All examinations were performed by a musculoskeletal radiologist.

A dynamic examination of the wrist was performed using a linear-array 17.5-MHz transducer on a Philips iU-22 (Philips Medical Systems, DA Best, The Netherlands). The wrist was initially scanned in the neutral position, both in sagittal and axial planes. A dynamic examination looking for movement of the median nerve was also performed in both planes. In those patients with lack of free movement of the median nerve in the carpal tunnel, an attempt was made to identify the site and extent of adhesion/fibrosis. The flexor tendons within the carpal tunnel were analyzed for the presence of an accessory muscle belly and tenosynovitis. Color and power Doppler were used to identify tenosynovitis more effectively. The flexor retinaculum was examined for adequacy of decompression. Persistent visualization of the flexor retinaculum after decompression, associated with flattening of the median nerve and reduced transverse subluxation, was considered as inadequate or incomplete decompression.

Results

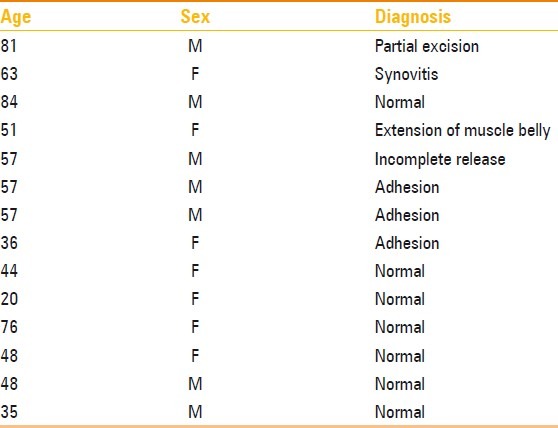

We found adhesion with scarring in three cases [Figure 2], exudative tenosynovitis within the carpal tunnel and proximal synovial bulge in one patient [Figure 3], inadequate decompression of the flexor retinaculum in two patients [Figures 4 and 5], and an anomalous muscle belly of the flexor digitorum superficialis tendon causing compression of the median nerve in one patient [Figure 6]. No cause was identified in 50% of the patients [Table 1].

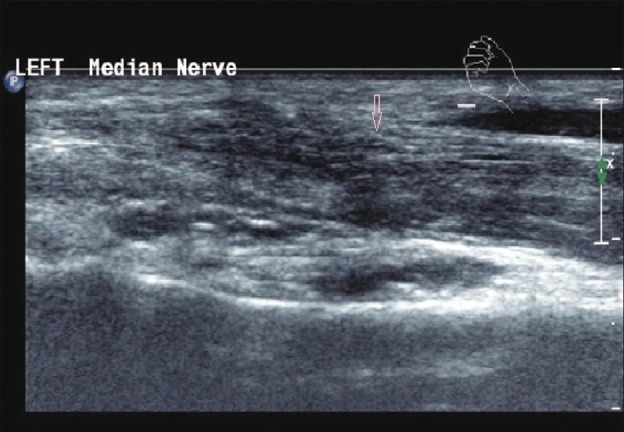

Figure 2.

A 36–year-old male with symptoms of CTS. Transverse USG shows scar tissue (arrow) at the site of decompression

Figure 3.

A 63-year-old female with symptoms of CTS. Longitudinal USG shows proximal synovial bulge (arrow) with hypoechoic exudative tenosynovitis

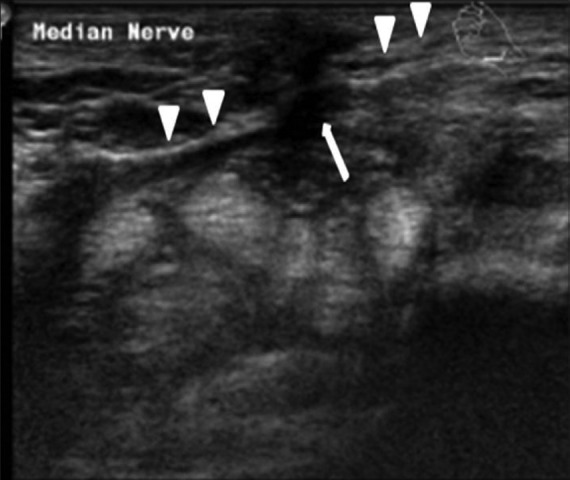

Figure 4.

A 57-year-old male with symptoms of CTS. Transverse USG shows scar tissue at the site of surgery (arrow) and incomplete division of the flexor retinaculum (arrowheads)

Figure 5.

57 year male with symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome. Transverse sonogram showing reformed flexor retinaculum (pink arrow) and flattened median nerve (blue arrow)

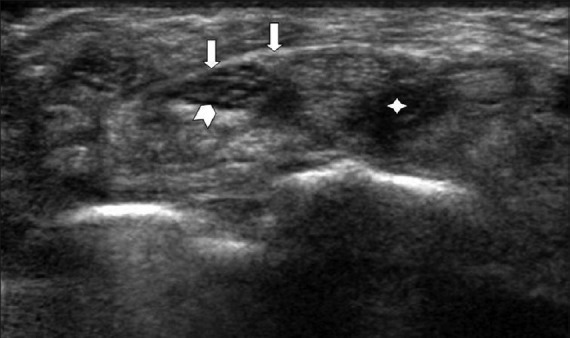

Figure 6.

A 54–year-old female with symptoms of CTS. Transverse USG shows reformed flexor retinaculum (arrow), median nerve (arrow head), and the muscle belly of the flexor digitorum profundus (star)

Table 1.

List of patients who had ultrasound for failed carpal tunnel decompression

Discussion

The recurrence rate following surgical decompression (open or endoscopic release) varies from 0% to 6%.[16]

Fibrosis accounts for the majority of cases of recurrence (up to 60%). Fibrosis that is superficial to the median nerve (superficial fibrosis) and the fibrosis that is deep to the median nerve (deep fibrosis) may both be associated with tethering of the nerve to the scar.[11] Dynamic USG with dorsiflexion and volar flexion of the wrist enables the radiologist to assess the median nerve in the sagittal plane. Transverse subluxation of the median nerve can also be assessed with flexion and extension of the fingers while scanning. Normally, one can appreciate free movement of the nerve within the carpal tunnel. The presence of fibrosis tethers the nerve to the scar or deeper structures, hampering the free gliding of the nerve. USG helps to guide the surgeon by identifying the site and the extent of fibrosis and demonstrating the tethering/adhesions.

Tenosynovitis of the flexor tendons is also one of the causes for recurrence of symptoms after carpal tunnel release. USG can demonstrate swollen and edematous flexor tendons with synovial prominence within the carpal tunnel. Hypervascularity is demonstrated on power and color Doppler study. USG helps to manage these patients without surgical intervention.

USG also quizzes the flexor tendons and enables one to detect accessory muscles. Schon et al. have described an anomalous muscle belly of the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) causing carpal tunnel syndrome.[9] Extrinsic compression of the nerve due to tumor, cyst, or ganglion can also be identified by ultrasound.

In conclusion, radiologists should acquaint themselves with the common USG findings in these cases as these findings can accurately guide the surgeon during re-exploration and help in resolution of the symptoms with as low morbidity as possible.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Ho PC. Carpal tunnel syndrome. Hong Kong Med J. 2007;13:340–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordstrom DL, Vierkant RA, DeStefano F, Layde PM. Risk factors for carpal tunnel syndrome in a general population. Occup Environ Med. 1997;54:734–40. doi: 10.1136/oem.54.10.734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamolz LP, Schrögendorfer KF, Rab M, Girsch W, Gruber H, Frey M. The precision of ultrasound imaging and its relevance for carpal tunnel syndrome. Surg Radiol Anat. 2001;23:117–21. doi: 10.1007/s00276-001-0117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerritsen AA, de Krom MC, Struijs MA, Scholten RJ, de Vet HC, Bouter LM. Conservative treatment options for carpal tunnel syndrome: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Neurol. 2002;249:272–80. doi: 10.1007/s004150200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Botte MJ, von Schroeder HP, Abrams RA, Gellman H. Recurrent carpal tunnel syndrome. Hand Clin. 1996;12:731–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steyers CM. Recurrent carpal tunnel syndrome. Hand Clin. 2002;18:339–45. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0712(01)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stutz N, Gohritz A, van Schoonhoven J, Lanz U. Revision surgery after carpal tunnel release: Analysis of the pathology in 200 cases during a 2 year period. J Hand Surg Br. 2006;31:68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frick A, Baumeister RG. [Re-intervention after carpal tunnel release] Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2006;38:312–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schon R, Kraus E, Boller O, Kampe A. Anomalous muscle belly of the flexor digitorum superficialis associated with carpal tunnel syndrome: Case report. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:969–70. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199211000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchberger W, Judmaier W, Birbamer G, Lener M, Schmidauer C. Carpal tunnel syndrome: Diagnosis with high resolution sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:793–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.159.4.1529845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campagna R, Pessis R, Feydy A, Guerini H, Le Viet D, Corlobé P, et al. MRI assessment of recurrent carpal tunnel syndrome after open surgical release of the median nerve. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:644–50. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong KC, Hung LK, Ho PC, Wong JM. Carpal tunnel release. A prospective randomised study of endoscopic versus limited open methods. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:863–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinilla I, Martín-Hervás C, Sordo G, Santiago S. The usefulness of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2008;33:435–9. doi: 10.1177/1753193408090396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iannicelli E, Almberger M, Chianta GA, Salvini V, Rossi G, Monacelli G, et al. High resolution ultrasonography in the diagnosis of the carpal tunnel syndrome. Radiol Med. 2005;110:623–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keleş I, Karagülle Kendi AT, Aydin G, Zöğ SG, Orkun S. Diagnostic precision of ultrasonography in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84:443–50. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000163715.11645.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ya’ish F, Power DM. Carpal Tunnel Release: Endoscopic or open? Internet J Hand Surg. 2007:1. [Google Scholar]