Abstract

Objective:

To describe intensive care unit (ICU) facilities in Sri Lanka; to describe the pattern of admissions, case-mix and mortality; compare patient outcome against the various types of ICUs; and determine the adequacy and standards of training received by medical and nursing staff.

Materials and Methods:

Observational study of multidisciplinary (general) and adult speciality ICUs in government sector hospitals.

Results:

Hospitals studied had 1 ICU bed per 100 hospital beds. Each bed catered to 70-90 patients over a year. Death rates were comparable in each level of hospital/ICU despite differences in resource allocation. Fifty to 60% of patients had their original problems related to medicine, while only 35% - 45% were surgical. Thirty two percent of medical patients and 15% of surgical patients died. More than 90% of ICUs had a multi-monitor for each bed. Seventy seven percent of ICUs had one or more ventilators for each bed. Arterial blood gas (ABG) facilities were available in 83% of ICUs. There were serious inadequacies in the availability of facilities of 24 hour physiotherapy (available only in 36.7%), 24 hour in hospital Ultra Sonography (22.4%), electrolyte analyser in ICU (54.2%), haemodialysis / continuous renal replacement therapy (HD/CRRT) (41.7%), and Echocardiography. Medical Officers’ training was anaesthetics dominated as opposed to a multidisciplinary training. There was a severe shortage of critical care trained nurses.

Conclusions:

Only limited evolution has taken place in intensive care over the past 5 years. The reasons for higher death rates in medical patients should be investigated further. Moving towards a multidisciplinary approach for training and provision of care for ICU patients is recommended.

Keywords: Critical care medicine, intensive care medicine, multidisciplinary approach

INTRODUCTION

Critical care medicine has evolved on the principle that patients with serious illness are better managed when grouped to a separate area, and treated by a dedicated team of healthcare providers. The earliest recorded instance of this was in 1854, when Florence Nightingale separated the critically wounded soldiers of the Crimean war into a separate area in the hospital, resulting in a reduction of mortality from 40% to 2%.[1,2] In 1926, Walter Dandy managed postoperative neurosurgical patients in a 3 bed critical care setup in Boston. Peter Saber established the concept of advanced life support and managed the critically ill in an intensive care environment in 1950. In 1953, Bjorn Ibsen established the first intensive care unit (ICU) in Copenhagen during the polio epidemic. The United States of America (USA) popularised their initial ICUs in the late 1950s.[2] Over the years, intensive care has shifted from open ICUs, where physicians and anaesthetists with other commitments provide care to patients in a segregated area of the hospital, to ‘closed’ ICUs, with dedicated specialist doctors and nurses with focussed critical care training (known as intensivists). Critical care medicine has two fundamental components in the provision of care: vital organ support and root cause identification and treatment. Traditionally, anaesthetists have been trained to provide vital organ support, based on their skills in intubation and familiarity with respiratory and haemodynamic support, while physicians/paediatricians have provided root cause identification and management. In the developed countries, this model has moved towards a model of having dedicated trained intensive care specialists, a merger of the required skills of these separate specialists. Most countries in the developed world and many in the developing world have dedicated intensive care training programs, producing intensivists to man the ICUs.

In Sri Lanka, the National Hospital of Sri Lanka (formerly Colombo General Hospital) had the first ICUs in Sri Lanka. The Recovery Unit for post-surgical patients was started in the late 1960s, and was soon followed by the Medical ICU. The Sri Lanka Society of Critical Care and Emergency Medicine was formed in 2002. In 2008, the Post Graduate Institute of Medicine introduced the Post Graduate Diploma in Critical Care Medicine, which was the first formal attempt to establish critical care training in the country.[3] So far intensive care units have been managed by anaesthetists, physicians, paediatricians and other specialists with varying degrees of intensive care training obtained overseas.

In 2003/04, Goonasekara et al., audited the Intensive Care Services of Sri Lanka.[1] In this audit, 49 ICUs in the government sector hospitals were studied, and it was shown that 57.1% of them were in the Teaching Hospitals. Nearly a half (51%) of the ICUs were ‘General’ type ICUs which accepted patients from multiple areas of specialities requiring a multidisciplinary approach for their management. A ventilator: Bed ratio of 1:1 or more was seen only in 57%. Goonasekara et al., concluded that the standards and management strategies practiced in these ICUs varied widely, and suggested that the inability to host closed-type ICUs in the country was a reflection of the non-availability of sufficient numbers of medical and nursing specialists in intensive care.

In this paper, we attempt to determine where Sri Lanka stands in the chain of Evolution of Critical Care in the world. We attempt to describe ICU facilities in Sri Lanka; i.e., to describe admissions, case-mix and mortality, to compare patient outcome against the various types of ICUs, and to determine the adequacy and standards of training received by ICU medical staff.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a cross-sectional observational study of all adult intensive care units in state sector hospitals in Sri Lanka. A list of ICUs was prepared based on information obtained from Ministry of Health. All government sector ICUs, i.e., multidisciplinary, adult surgical, adult medical, and obstetrical and gynaecological critical care services were included. Three ICUs of the government hospitals did not consent to take part in the study. Private sector ICUs were not included due to administrative reasons. All paediatric, paediatric sub-speciality and neonatal ICUs were also excluded. Data was obtained from total of 51 ICUs.

A structured questionnaire was administered over the telephone to obtain the relevant information. A sister or a senior nurse, and a medical officer, working in the particular ICU took part in information giving. Where relevant information was not readily available, another interview was scheduled after 2 weeks. Information gathered included bed numbers, admissions and deaths during the year 2008, availability of facilities and staff characteristics, and in particular, training acquired by the medical staff. We analysed our data using Microsoft Excel 2007™

RESULTS

Types of ICUs, turnover and outcome

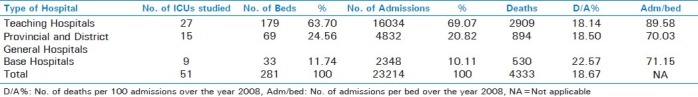

We classified the ICUs according to the type of hospitals where they were situated in Table 1. Nearly 64% of the ICU beds were located in the teaching hospitals. Teaching hospitals had a high turnover (i.e., admissions/bed): 90 admissions per bed per year. All hospital categories had comparable death rates (deaths/admissions %) despite the fact that resource allocation was likely to be different. On average, teaching hospitals had 8 ICU beds per 1000 hospital beds, while Provincial General Hospitals (PGH)/ District General Hospitals (DGH) and Base hospitals had around 10/1000. This is well below the international norm of 10-40 ICU beds per 1000 hospital beds. The average bed strength, taking all ICUs into consideration, was 5 per ICU.

Table 1.

Beds, admissions and deaths in the Intensive Care Units according to type of hospital in ths study

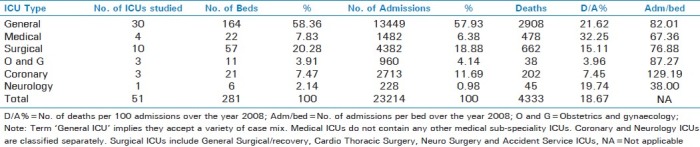

Table 2 classifies the ICUs according to type or designation. Fifty eight percent of the beds were in General ICUs, and accommodated 58% of admissions. ‘Admission/bed’ may reflect the duration taken for recovery rather than bed occupancy; this was lowest in neurology ICUs, and also low in medical ICUs.

Table 2.

Beds, admissions, and deaths classification according to type of Intensive Care Units in the study

There is a high turnover in coronary beds. The low death rate seen in Coronary ICUs may be due to the fact that since the two coronary ICUs in the National Hospital Colombo (NHSL) do not have adequate ventilator facilities (only one ventilator available for 16 coronary beds), their patients needing ventilators (and thus being more critically ill) are transferred to other ICUs in the NHSL complex, thus understating coronary deaths.

There was a significant difference in the death rates in medical and surgical ICUs (32% vs. 15%). General ICUs had a death rate of 21.6%. When this death rate was split and weighted according to the case mix of general ICUs (approx. 50% medical vs. 35% surgical admissions), the death rates of medical and surgical patients in general ICUs were similar to their counterparts in respective designated ICUs.

Case-mix in ICUs

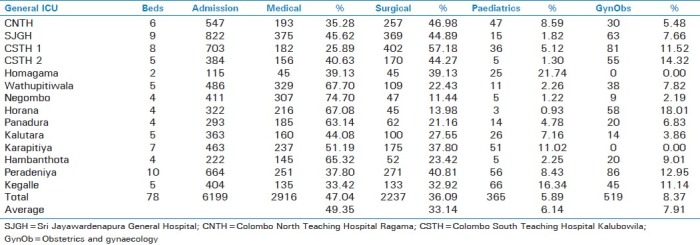

Out of the 30 General ICUs we studied, only 14 had their admissions classified. We analysed the admissions of these 14 ICUs according to the speciality under which they were admitted. Here, medical admissions include all medical sub-specialities and surgical admissions include all surgical sub-specialities [Table 3].

Table 3.

Admission Analysis of General Intensive Care Units according to the referring speciality

Overall, approximately 50% admissions were for medical problems and 35% were surgical. Medical and paediatric comprised 55%, while surgical and Obstetrics and gynaecology (OandG) comprised 45%. Both Medical and Surgical admission distributions were bi-modal, depicting the differences in teaching hospitals and peripheral hospital ICUs. Peripheral hospitals had higher medical admission rates and lower surgical admission rates (modes: 65% and 25% respectively), compared with teaching hospital ICUs which had higher surgical and lower medical admission rates (modes: 45% and 35% respectively). All the General ICUs had comparable Paediatric and OandG admissions, which were less than 25%.

Staffing

All general and surgical ICUs were headed by a consultant anaesthetist. This group comprised of 39 ICUs. Six medical ICUs and 4 medical sub-speciality ICUs were headed either by a consultant physician, or a consultant in the relevant sub-speciality. The lead role was uncertain in 2 ICUs. All the consultant anaesthetists who did rounds in ICUs, also shared work with operating theatres. There were 427 Medical Officers (MOs) manning these ICUs. Out of them only 256 were designated as ‘MO-ICU’ dedicating themselves only to the ICU. The rest of 171 shared work in anaesthesiology (operating theatre) and ICU.

The training that the ICU MOs received was inconsistent. Most of those who were designated as ‘MO/ICU’ had received 3 – 6 weeks of training in endotracheal intubation and Intensive care in general. Only a few had had the privilege of having their training in a teaching hospital. The place and duration of the training varied enormously depending on the service requirement of the station they were appointed to. Those who were sharing work in Anaesthesiology and ICU had a more specified training in anaesthesiology for 6 months, which included an inconsistent duration of 0-4 weeks of ICU training.

Almost none had received any special training in paediatrics, cardiology, renal therapy or other organ support therapy (except ventilation). The prevailing general ICU training only minimally covered a systematic multidisciplinary training. After the initial training they received, none had received any further systematic in-service training, other than the voluntarily particiaption in occasionally held workshops. The Sister or the nurse-in-charge of the ICUs were minimally trained and ICU trained sisters had received special training in only in 16 (29%) of the 55 ICUs studied. This is one of the key factors in categorising the level of an ICU. The critical care trained: total nursing staff ratio varied widely amongst the ICUs.

Available facilities

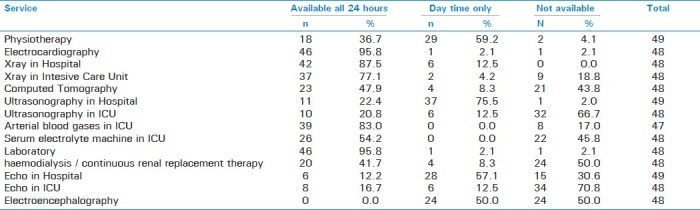

More than 90% of the ICU beds were equipped with a multifunction monitor. Eighteen ICUs (77.4%) had equal to or more than 1:1 ventilator: bed ratio. We gathered data on the availability of allied health services from 49 ICUs [Table 4]. We observed serious inadequacies in the availability of facilities for 24 hour physiotherapy (36.7%), 24 hour in-hospital ultrasound scanning (22.4%), serum electrolyte measurement in ICU (54.2%), HD/CRRT (41.7%), and echocardiography. Whilst several ICUs had recently acquired serum electrolyte and ABG machines, these were unable to measure the chloride and lactate levels.

Table 4.

Availability of allied services in the Intensive Care Units

Limitations

This study has not described the paediatric, neonatal and private sector hospital ICUs. Only a few ICUs had maintained the records of rejected admission requests. None had kept the records of patients who were transferred to other hospitals in need of intensive care due to non-availability of beds in their own ICU. An analysis on the rejected/failed to accommodate requests would have illustrated the ICU care seeking patterns. Many general ICUs had not classified their admissions according to the patient referring speciality.

The majority of the hospitals did not have an inter-department analysis of local purchase, expenses, resource allocation etc, the presence of which would have highlighted the burden of Intensive care on resources.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Modern critical care is not limited to post operative care or mechanical ventilation. It is a separate speciality and although some period of training in an ICU is valuable to all specialities, it can no longer be regarded as a part of anaesthesia, medicine, surgery or any other discipline.[4] The Australasian and European experiences have favoured the development of general/multidisciplinary ICUs.[5] Thus with the exception of dialysis units, coronary care units and the neonatal care units, critically ill patients are admitted to the multidisciplinary ICU or the Paediatric ICU as appropriate.[4]

A hospital needs 1-4 ICU beds per 100 hospital beds.[4] A general ICU with 6-10 beds is an optimal ICU, when standards and cost effectiveness are considered.[5] The ICU should be able to accept at least 95% of all emergency requests.[5–7] While multi monitoring, nursing and ventilatory support facilities are essential on 1:1 basis, an in house laboratory with the capabilities of analysing blood gases, glucose, electrolytes, haemoglobin, lactate and clotting profile is deemed optimal.[4] Around the clock support of the departments of physiotherapy, radiology, pathology, cardiology, microbiology and pharmacy cannot be undervalued.

ICUs of level 2 or 3 (in the local context, these are the ICUs of District General and Teaching hospitals) must have at least one specialist exclusively rostered to the unit at all times. This specialist should have a significant or full time commitment to the ICU ahead of clinical commitments elsewhere.[4,5] The minimum number of fixed consultant sessions per week should be ten.[5] A qualified medical officer must be available in house around the clock.[5,7]

In any hospital setting, the ICU is held responsible for a significant proportion of the hospital's expenses in terms of financial, physical and human resources. In many occasions, ICU becomes the department that makes the most expensive local purchases. A few studies have made attempts to analyse the costs involved in ICUs of Sri Lanka.[8] However, there are hardly any studies which have tried to audit the cost effectiveness of this expenditure.

It is in this context, many countries have adopted regulations and recommendations to maintain the standards in a cost effective manner. While a qualified Consultant Intensivist takes a lead role, intermediate level training and certification is provided to the general medical officers involved in critical care services. Some countries go further and provide specialised certification for nursing in critical care (eg. American Society of Critical Care Nurses).[9]

It was revealed in our study that the total number of ICU beds in this country has not increased significantly during the past five years. The depicted rise in ICU beds of provincial general hospital (PGH)/ district general hospital (DGH) hospital category is due to the status elevation of some of the Base Hospitals into PGH/DGH status. The mortality ratios of the ICUs of different types of hospitals were comparable, but the teaching hospital ICUs had a higher bed turnover.

Some of the allied facilities have improved, especially in the numbers of nursing, ventilators, multi monitors, ABG and serum electrolyte (SE) machines. Many authorities recommend 24 hour access to radiology, physiotherapy, laboratory and pharmacy departments.[5–7] However, serious lacking yet prevails in certain allied services especially, physiotherapy.

It is recommended that a post registration ICU qualified sister be in charge of the nursing care in at least level II and above ICUs. Only 16 (38.1%) such sisters were available in 42 level II and above ICUs studied. All ICUs in the country were managed by consultants who are have their own speciality work load such as anaesthesia, involving a considerable workload in operating theatres and/or physicians managing busy wards and clinics. Even though it is recommended, Sri Lankan hospitals have no dedicated specialists to serve and effectively manage the enormous amount of finances, physical resources and the clinical problems of the ICU. The majority of the clinical problems encountered in ICUs have had their origins in the fields of medicine or medical sub specialities. Current medical staff training is not geared to cater the case mix patterns. Anaesthesiology-dominated training must be changed over to a more systematic training with multidisciplinary input and approach. In this regard, we applaud the Post Graduate Institute of Medicine of Sri Lanka, (PGIM's) introduction of PG Diploma in Critical Care Medicine, which has addressed the issue to a certain extent. We criticise the recent decision taken by the Ministry of Health to stop appointing designated MO/ICUs, but to appoint MO/anaesthesia cum ICU, which has lead to inappropriate training, wastage of resources and skill, and created administrative problems in having combined rosters for ICU and Operating Theatre.

It is reasonable to infer that in our set up, around a third of medical patients and one sixth of surgical patients would die, irrespective of the type of ICU in which they were managed, or by the speciality of the consultant by whom they were managed. This itself shows that a multi-disciplinary approach is required especially for medical ICUs as well as general ICUs, which contain mostly medical problems. The reasons for higher death rates in medical patients have to be investigated further.

When compared with the 2004 analysis of Gunasekara et al.,[1] hardly any evolution has occurred in the areas of bed numbers, staffing, staff training and availability of allied facilities. Physical resources have improved in the areas of availability of ventilators, multifunction monitors and other devices of intensive care.

In conclusion, we strongly recommend that concerned authorities – namely the Ministry of Health and the Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, with the support of the relevant Colleges and the Government Medical Officers Association should promote the emergence of critical care specialists or ‘Intensivists’ in Sri Lanka. This will fulfil a long felt need and will definitely improve the quality of care received by critically ill patients in this country.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank all the Medical Officers, Sisters in charge, and nurses of the ICUs who provided valuable information. We also wish to thank Professor CDA Gunasekara, Dr. K H Sellahewa, and Dr. A Munasinghe for their guidance.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yatawatte AB, Wanniarachchi CR, Goonasekara CD. An audit of the state sector Intensive Care Services of Sri Lanka. Ceylon Med J. 2004;42:51–4. doi: 10.4038/cmj.v49i2.3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.History: In Intensive Care Medicine. [Last accessed on 2011 Jun 13]. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intensive_Care_Medicine .

- 3.Sheriff R. Critical care, Who cares (Editorial) SLMA News. 2009;10:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawker F. Design and organisation of Intensive Care Units. In: Bersten AD, Soni N, editors. Oh's Intensive Care Manual. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Limited; 2009. pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 5.“Standards for Intensive Care Units. Policy Document 1997; Intensive Care Society (UK) Accessed 8th February 2012 from http://www.ics.ac.uk/intensive_care_professional/standards_and_guidelines/standards_for_intensive_care_2007. ” .

- 6.2003. Minimum Standards for Intensive Care Units, Policy Document IC-1; Joint Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine, Melbourne.

- 7.2006. Minimum Standards for Intensive Care Units in the Government Hospitals of Sri Lanka; Society of Critical Care and Emergency Medicine.

- 8.Dassanayaka JH. MSc (Community Medicine) dissertation, Post graduate Institute of Medicine. Colombo: 2008. Cost per patient day in the Intensive care unit, and cost awareness among medical and nursing officers at the Base Hospital, Horana. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Certification, Education, Clinical Practice. In American Association of Critical Care Nurses. [Last accessed on 2011 Jun 13]. Available from: http://www.aacn.org .