Abstract

A 56-year-old female, recently (3 months) diagnosed with chronic kidney disease (CKD), on maintenance dialysis through jugular hemodialysis lines with a preexisting nonfunctional mature AV fistula made at diagnosis of CKD, presented to the hospital for a peritoneal dialysis line. The recently inserted indwelling dialysis catheter in left internal jugular vein had no flow on hemodialysis as was the right-sided catheter which was removed a day before insertion of the left-sided line. The left-sided line was removed and a femoral hemodialysis line was cannulated for maintenance hemodialysis, and the next day, a peritoneal catheter was inserted in the operation theater. However, 3 days later, there was progressive painful swelling of the left hand and redness with minimal numbness. The radial artery pulsations were felt. There was also massive edema of forearm, arm and shoulder region on the left side. Doppler indicated a steal phenomena due to a hyperfunctioning AV fistula for which a fistula closure was done. Absence of relief of edema prompted a further computed tomography (CT) angiogram (since it was not possible to evaluate the more proximal venous segments due to edema and presence of clavicle). Ct angiogram revealed central vein thrombosis for which catheter-directed thrombolysis and venoplasty was done resulting in complete resolution of signs and symptoms. Upper extremity DVT (UEDVT) is a very less studied topic as compared to lower extremity DVT and the diagnostic and therapeutic modalities still have substantial areas that need to be studied. We present a review of the present literature including incidences, diagnostic and therapeutic modalities for this entity. Data Sources: MEDLINE, MICROMEDEX, The Cochrane database of Systematic Reviews from 1950 through March 2011.

Keywords: AV fistula, catheter thrombolysis, unilateral upper limb edema, upper extremity deep vein thrombosis

INTRODUCTION

Up to 10% of all deep vein thrombosis (DVT) are related to upper extremity, occurring at an incidence of about 3 per 100,000 in the general population.[1–3]

However, this figure is probably an underestimation of the actual problem as a large number of upper extremity deep vein thrombosis (UEDVT) goes undetected since the problem is generally asymptomatic, especially in patients who have repeated central vein cannulations or indwelling lines and port.

The incidence of UEDVT is much less than that of the lower extremity DVT possibly because:

fewer, smaller valves are present in the veins of the upper extremity,[4]

bedridden patients generally have less cessation of arm movements as compared to leg movements,

less hydrostatic pressure in the arms, and

increased fibrinolytic activity that has been seen in the endothelium of the upper arm as compared to the lower arm.[5,6]

Absence of a similar soleal network of veins may also contribute to the lesser incidence of UEDVT.

The incidence of thrombosis in the upper extremity is seen maximally in the subclavian vein (18–67%), followed by axillary (5–25%) and the brachial (4–11%),[7–9] with marked predilection for the left side, probably as a result of anatomical reasons as explained elegantly by Stephen et al., in 1979.[10]

Usually, UEDVT generally occurs in more than one segment of the veins at a time. Prevalence and incidence rates also seem to denote that larger the catheter inserted, higher the chances of a DVT indicating that the peripherally inserted central lines probably have a reduced incidence of UEDVT.[11]

CLASSIFICATION

There are many types of classifications suggested by various authors. Coon and Willis classifed UEDVT into two divisions:

traumatic which may be internal (like central venous cannulation or external (like fracture, stress) and

spontaneous (like cancer or idiopathic).[2]

Others have classified it as primary (idiopathic, thoracic outlet syndrome, Paget–Schroetter syndrome) and secondary (catheter, cancer or surgery associated).[12] For the purpose of this review, thoracic outlet syndrome and similar forms of primary DVT are not considered and emphasis is laid on secondary forms of DVT.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The classical presentation of UEDVT is the presence of arm discomfort, edema, discoloration, pain, and dilated venous collaterals. The level of suspicion increases in the presence of risk factors like presence of indwelling catheters and vigorous arm exercise.

COMPLICATIONS

The main complication remains mortality, recurrent thromboembolism and the worrisome post-thrombotic syndrome. The mortality rate ranges from 10 to 50%, related mainly to the underlying malignancy, and fatal pulmonary embolism also sometimes contributes to the overall mortality.[13,14]

Pulmonary embolism complicates UEDVT in 36% of cases and seems to be more common with carriers of central venous catheters.[15,16]

DIAGNOSIS AND INVESTIGATIONS

The clinical and diagnostic work up of DVT of the lower extremities is established. However, the same cannot be said about UEDVT.

Contrast venography is the reference standard for the diagnosis of UEDVT.

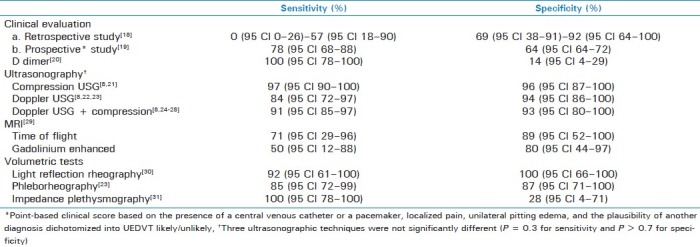

An elegant systematic review of 17 papers by Di Nisio et al.[17] sheds some light on the diagnostic values of various methods to diagnose UEDVT.

The highlights of the study are tabulated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic modalities

The above available evidence does seem to suggest, as reiterated by Di Nisio et al., that ultrasonography (USG) is probably the first choice for investigating UEDVT, and venography is resorted to only in the context of a disparity between USG and clinical findings, though it is very important to note that most of the studies are of relatively small size and poor quality, laying major doubt on the accuracy of the tests.

It is also not known whether recurrent thrombosis risk prediction models which use a combination of the above-mentioned clinical and diagnostic tests (like the Vienna prediction model) as developed and validated for lower limb DVT can be applicable to the cohort of UEDVT.[32,33]

MANAGEMENT

The paucity of large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and studies places optimal management of UEDVT as one of the most controversial areas of therapy, with the options being

physical measures (surgical thrombectomy, mechanical therapy),

anticoagulant, and

thrombolytics.

Surgical thrombectomy

Open surgical iliofemoral thrombectomy was one of the approved therapies in the management of acute DVT of the lower limbs. Presently, this approach is reserved for those who have contraindications to pharmacological therapies. The Fogarty balloon thrombectomy catheters have predominantly facilitated this approach.

In a comparison between surgical thrombectomy and anticoagulation alone, post-thrombotic symptoms of leg edema, venous claudication, varicose veins were more frequent in the anticoagulation group (42% vs. 7%; P < 0.005)[34] with greater than twofold patency rates in the thrombectomy group (76% vs. 35%; P < 0.025) as compared to the anticoagulation group, as demonstrated by venography with higher degree of valvular incompetence in the anticoagulant group. Thus, it does seem that surgical thrombectomy has an important role in the management of acute DVT of the lower limb. Whether the same holds good for UEDVT is not known at the moment as similar studies in UEDVT are not available.

Anticoagulant therapy

Level I evidence from RCTs has established the efficacy and safety of treatment of DVT with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH).[34–37] The safety, predictable antithrombotic efficacy, ease of dosing, and absence of the immune-mediated, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia favors use of LMWH over heparin except in conditions where the predictability of dose effect is reduced as in renal failure. Heparin is thus continued till warfarin therapeutic International Normalized Ratio (INR) is achieved. Based on level I and II evidence, the usual dose of warfarin is 5–10 mg on the first day and 5 mg daily thereafter.[38,39] Cohort studies with low recurrence rates indicate that the optimum duration of anticoagulation is for a period of 3–6 months;[41,42] however, the evidence for this at best is moderate as there are no controlled studies which have established the optimum duration.

However, in those patients who present with massive DVT clinically, i.e. massively swollen limb, acrocyanosis, severe pain, or worse, ischemia, this form of therapy (i.e. anticoagulant alone) may be an inferior form of therapy as such patients are more than twice as likely to develop extension of thrombosis as patients with less extensive DVT (11.2% vs. 5.3%),[40] warranting the use of multimodal therapy.

Thrombolysis

Administration of thrombolytics in order to dissolve the clot could be done by two methods:

Systemic

Local (catheter-directed thrombolysis or CDT)

Systemic thrombolysis

Systemic thrombolysis for fully obstructed segments of veins with DVT does not have as much therapeutic efficacy as that seen in coronary thrombolysis, primarily because of inefficient diffusion of the thrombolytic agent in the large venous thrombi matrix coupled with low flow conditions,[43–46] which is reinforced in a study where complete (50–100%) thrombus dissolution occurred in approximately 50% of venous segments with nonobstructive thrombi but in only 10% of fully obstructed segments.[46,47]

This approach, as compared to anticoagulation alone, is also associated with a very high risk of bleeding related complications,[48–50] which thus has paved the way for catheter directed thrombolysis.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis

This involves passage of a catheter to the thrombus bed and instillation of small continuous doses of fibrinolytic agent into the thrombus in anticipation of resolution of the clot.

A 3-point scale has been proposed to define outcomes of therapy for DVT, with grades 2 and 3 signifying at least 50% luminal patency post lysis. This is classified as a satisfactory therapeutic outcome. Grade 1is classified as <50% lysis or unsatisfactory outcome.[51]

Favorable patency rates were observed when CDT was compared with anticoagulation and compression stockings as per the recent follow-up result of the CaVenT study conducted in Norway.[52]

Immediate grade 2 to 3 lysis was observed in 40% of patients post procedure and the 6-month patency rates were almost double when compared to anticoagulation alone, with an absolute risk reduction of 28% (95% CI 9.7–46.7%; P < 0.004). The above trial, though done in lower limb DVT, does indicate superior clot lysis in the acute setting with CDT, with better long-term venous patency rates in comparison with anticoagulation alone.

Other ongoing trials, namely the ATTRACT and the UK-RCT, are awaited.

Relation to timing of intervention

The effectiveness of the CDT may also depend on the timing as it is known that freshly formed thrombi are more amenable to thrombolysis as compared to organized thrombosis. Several small studies like the one done by Vik et al.[53–56] have indicated that early therapy (within 10–14 days) gives superior results in UEDVT.

Relation to quantity of clot removed

The prognosis also seems to depend significantly on the quantity of clot removed. The degree of clot lysis directly correlates with long-term outcome as shown by Grewal and coworkers in their paper which depicts the relation between quantity of clot lysed and the relation with post-thrombotic morbidity.[57]

Safety

CDT is also a safe procedure as proved by Kim et al. in their study, where CDT was used to treat 202 limbs in 178 patients (75 limbs in 61 cancer patients and 127 limbs in 117 patients without cancer), in which 3 cancer patients (4.9%) and 4 non-cancer patients (3.4%) experienced major bleeding during CDT (P = 0.6924). Pulmonary embolism occurred in 1.6% (1 of 61) of cancer patients and in 1.7% (2 of 117) of patients without cancer (P = 0.9999) during CDT.[58]

At this point it is important to note that the large trials of DVT like the CaVenT, ATTRACT, etc., are carried out in cohorts of patients with lower limb DVT.

In the absence of large-scale RCTs in upper limb DVT, it is still not clear whether extrapolation of results from the trials in lower limb DVT can be applied to UEDVT, though it logically appears to stand good.

With respect to the above modality of treatment (i.e., CDT), current guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) suggest that CDT should be used in those with life expectancy of more than 1 year, good functional status, extensive iliofemoral thrombosis, and presenting soon after (less than 14 days) the onset of symptoms (level 2B evidence). The guidelines also advocate the use of venous angioplasty and stenting in the presence of reversible causes of thrombosis and discuss the efficacy of dual therapy with pharmacomechanical therapy (PMT).[51]

Thus, international treatment guidelines now recognize the importance of thrombus removal to reduce post-thrombotic morbidity when treating patients with extensive acute DVT.

Mechanical devices

Two basic forms of motorized mechanical devices exist:

rotational and

hydrodynamic.

The rotational devices have a potential for injuring the endothelium of the veins and are known to embolize resultant small particles into the pulmonary circulation.[59–61] New rotational devices with guards to circumvent the above problem are available; however, clinical data on the same are sparse.

Hydrodynamic devices may probably cause less damage to venous endothelium as compared to the rotational devices. This, however, needs to be confirmed with a large clinical trial. A small study has reported approximately greater than 50% clot extraction in approximately 59% of the total, leading to symptomatic improvement in almost 82% of cases.[62]

Multimodal therapy

Motorized mechanical devices are generally used in conjunction with pharmacological thrombolysis and hence called as pharmacomechanical therapy (PMT) and this form of therapy seems to be superior when compared to any one used singly.

In a study comparing treatment outcomes, CDT or PMT was performed in 46 (47%) and 52 (53%) procedures respectively. In the CDT group, complete and partial thrombus removal was accomplished in 32 (70%) and 14 (30%) cases, respectively. In the PMT cohort, complete and partial thrombus removal was accomplished in 39 (75%) and 13 (25%) cases, respectively. Patency rate at 1 year remained nonsignificant between both the groups; however, significant reductions in the intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital lengths of stay were noted in the PMT group (0.6 and 4.6 days, respectively) when compared to the CDT group (2.4 and 8.4 days, respectively).[63]

Culprit lesions can be identified in certain patients with post-intervention angiography, which can usually be treated with percutaneous plasty and stenting procedures. Long-term patency rates of these procedures seem to be reasonably high; however, the data on this seem to be very less.[64–66]

CONCLUSIONS

High index of suspicion with prompt objective diagnosis, especially in patients with clinical features and central venous catheters, is important to diagnose the serious entity of UEDVT.

Till further studies are done, it seems safe to treat patients of asymptomatic mild UEDVT with anticoagulation alone and patients of severe or extensive UEDVT with PMT, depending upon the availability of expertise, without delay beyond 10–14 days. The recommendation in this review thus conforms to the recent ACCP guidelines published in this regard.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Joffe HV, Kucher N, Tapson VF, Goldhaber SZ. Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) FREE Steering Committee. Upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis: A prospective registry of 592 patients. Circulation. 2004;110:1605–11. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000142289.94369.D7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coon WW, Willis PW., 3rd Thrombosis of axillary and subclavian veins. Arch Surg. 1967;94:657–63. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1967.01330110073010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horattas MC, Wright DJ, Fenton AH, Evans DM, Oddi MA, Kamienski RW, et al. Changing concepts of deep venous thrombosis of the upper extremity-report of a series and review of the literature. Surgery. 1988;104:561–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gross CM, editor. Gray's anatomy, Anatomy of the Human Body. 28th American ed. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1966. p. 730. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pandolfi M, Robertson B, Isacson S, Nilsson IM. Fibrinolytic activity of human veins in arms and legs. Thromb Diath Haemorrh. 1968;20:247–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson BR, Pandolfi M, Nilsson IM. Response of local fibrinolytic activity to venous occlusion of arms and legs in healthy volunteers. Acta Chir Scand. 1972;138:437–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill SL, Berry RE. Subclavian vein thrombosis: A continuing challenge. Surgery. 1990;108:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prandoni P, Polistena P, Bernardi E, Coga A, Casara D, Verlato F, et al. Upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis. Risk factors, diagnosis, and complications. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marinella MA, Kathula SK, Markert RJ. Spectrum of upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis in a community teaching hospital. Heart Lung. 2000;29:113–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prescott SM, Tikoff G. Deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremity: A reappraisal. Circulation. 1979;59:350–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.59.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grove JR, Pevec WC. Venous thrombosis related to peripherally inserted central catheters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11:837–40. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61797-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sajid MS, Ahmed N, Desai M, Baker D, Hamilton G. Upper limb deep vein thrombosis: A literature review to streamline the protocol for management. Acta Haematol. 2007;118:10–8. doi: 10.1159/000101700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prandoni P, Bernardi E, Marchiori A, Lensing AW, Prins MH, Villaltta S, et al. The long-term clinical course of acute deep vein thrombosis of the arm: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2004;329:484–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38167.684444.3A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baarslag HJ, Koopman MM, Hutten BA, Linthorst Homan MW, Buller HR, Reekers JA, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with suspected deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremity: Survival, risk factors and post-thrombotic syndrome. Eur J Intern Med. 2004;15:503–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Becker DM, Philbrick JT, Walker FB., 4th Axillary and subclavian venous thrombosis. Prognosis and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1934–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hingorani A, Ascher E, Markevich N, Yorkovich W, Schutzer R, Mutyala M, et al. Risk factors for mortality in patients with upper extremity and internal jugular deep venous thrombosis. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:476–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Nisio M, van Sluis GL, Bossuyt PM, Buller HR, Porreca E, Rutjes AW. Accuracy of diagnostic tests for clinically suspected upper extremity deep vein thrombosis: A systematic review. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:684–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanley JM, McGrath RS, Freeman MB, Stevens SL, Goldman MH. Predictability of symptoms of upper extremity deep venous thrombosis in patients with central venous catheters with color duplex imaging. J Vasc Tech. 1994;18:71–3. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Constans J, Salmi LR, Sevestre-Pietri MA, Perusat S, Nguon M, Degeilh M, et al. A clinical prediction score for upper extremity deep venous thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99:202–7. doi: 10.1160/TH07-08-0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merminod T, Pellicciotta S, Bounameaux H. Limited usefulness of D-dimer in suspected deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremities. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2006;17:225–6. doi: 10.1097/01.mbc.0000220248.04789.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sullivan ED, Peter DJ, Cranley JJ. Real-time B-mode venous ultrasound. J Vasc Surg. 1984;1:465–71. doi: 10.1067/mva.1984.avs0010465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel MC, Berman LH, Moss HA, McPherson SJ. Subclavian and internal jugular veins at Doppler US: Abnormal cardiac pulsatility and respiratory phasicity as a predictor of complete central occlusion. Radiology. 1999;211:579–83. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.2.r99ma08579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Falk RL, Smith DF. Thrombosis of upper extremity thoracic inlet veins: Diagnosis with duplex Doppler sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:677–82. doi: 10.2214/ajr.149.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sottiurai VS, Towner K, McDonnell AE, Zarins CK. Diagnosis of upper extremity deep venous thrombosis using noninvasive technique. Surgery. 1982;91:582–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haire WD, Lynch TG, Lund GB, Lieberman RP, Edney JA. Limitations of resonance magnetic imaging and ultrasound-directed (duplex) scanning in the diagnosis of subclavian vein thrombosis. J Vasc Surg. 1991;13:391–7. doi: 10.1067/mva.1991.25130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knudson GJ, Wiedmeyer DA, Erickson SJ, Foley WD, Lawson TL, Mewissen MW, et al. Color Doppler sonographic imaging in the assessment of upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;154:399–403. doi: 10.2214/ajr.154.2.2136963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baxter GM, Kincaid W, Jeffrey RF, Millar GM, Porteous C, Morley P. Comparison of colour Doppler ultrasound with venography in the diagnosis of axillary and subclavian vein thrombosis. Br J Radiol. 1991;64:777–81. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-64-765-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baarslag HJ, van Beek EJ, Koopman MM, Reekers JA. Prospective study of color duplex ultrasonography compared with contrast venography in patients suspected of having deep venous thrombosis of the upper extremities. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:865–72. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-12-200206180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baarslag HJ, Van Beek EJ, Reekers JA. Magnetic resonance venography in consecutive patients with suspected deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremity: Initial experience. Acta Radiol. 2004;45:38–43. doi: 10.1080/02841850410003428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mukherjee D, Andersen CA, Sado AS, Bertoglio MC. Use of light reflection rheography for diagnosis of axillary or subclavian venous thrombosis. Am J Surg. 1991;161:651–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(91)91249-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patwardhan NA, Anderson FA, Cutler BS, Wheeler HB. Noninvasive detection of axillary and subclavian venous thrombosis by impedance plethysmography. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1983;24:250–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodger MA, Kahn SR, Wells PS, Anderson DA, Chagnon I, Le Gal G, et al. Identifying unprovoked thromboembolism patients at low risk for recurrence who can discontinue anticoagulant therapy. CMAJ. 2008;179:417–26. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eichinger S, Heinze G, Jandeck LM, Kyrle PA. Risk assessment of recurrence in patients with unprovoked deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism: The Vienna prediction model. Circulation. 2010;121:1630–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.925214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plate G, Einarsson E, Ohlin P, Jensen R, Qvarfordt P, Eklof B. Thrombectomy with temporary arteriovenous fistula: The treatment of choice in acute iliofemoral venous thrombosis. J Vasc Surg. 1984;1:867–76. doi: 10.1067/mva.1984.avs0010867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koopman MM, Prandoni P, Piovella F, Ockelford PA, Brandjes DP, van der Meer J, et al. Treatment of venous thrombosis with intravenous unfractionated heparin administered in the hospital as compared with subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin administered at home. The Tasman Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:682–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levine M, Gent M, Hirsh J, Leclerc J, Anderson D, Weitz J, et al. A comparison of low-molecular-weight heparin administered primarily at home with unfractionated heparin administered in the hospital for proximal deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:677–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Low-molecular-weight heparin in the treatment of patients with venous thromboembolism. The Columbus Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:657–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709043371001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kovacs MJ, Rodger M, Anderson DR, Morrow B, Kells G, Kovacs J, et al. Comparison of 10-mg and 5-mg warfarin initiation nomograms together with low-molecular-weight heparin for outpatient treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:714–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-9-200305060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harrison L, Johnston M, Massicotte MP, Crowther M, Moffat K, Hirsh J. Comparison of 5-mg and 10-mg loading doses in initiation of warfarin therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:133–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-2-199701150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martinelli I, Battaglioli T, Bucciarelli P, Passamonti SM, Mannucci PM. Risk factors and recurrence rate of primary deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremities. Circulation. 2004;110:566–70. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000137123.55051.9B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Savage KJ, Wells PS, Schulz V, Goudie D, Morrow B, Cruickshank M, et al. Outpatient use of low molecular weight heparin (Dalteparin) for the treatment of deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremity. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:1008–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Douketis JD, Crowther MA, Foster GA, Ginsberg JS. Does the location of thrombosis determine the risk of disease recurrence in patients with proximal deep vein thrombosis? Am J Med. 2001;110:515–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00661-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown WD, Goldhaber SZ. How to select patients with deep vein thrombosis for tpa0 therapy. Chest. 1989;95(Suppl 5):276S–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.95.5_supplement.276s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blinc A, Kennedy SD, Bryant RG, Marder VJ, Francis CW. Flow through clots determines the rate and pattern of fibrinolysis. Thromb Haemost. 1994;71:230–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blinc A, Francis CW. Transport processes in fibrinolysis and fibrinolytic therapy. Thromb Haemost. 1996;76:481–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meyerovitz MF, Polak JF, Goldhaber SZ. Short-term response to thrombolytic therapy in deep venous thrombosis: Predictive value of venographic appearance. Radiology. 1992;184:345–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.184.2.1620826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ott P, Eldrup E, Oxholm P, Vestergard A, Knudsen JB. Streptokinase therapy in the routine management of deep venous thrombosis in the lower extremities. A retrospective study of phlebographic results and therapeutic complications. Acta Med Scand. 1986;219:295–300. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1986.tb03314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldhaber SZ, Buring JE, Lipnick RJ, Hennekens CH. Pooled analyses of randomized trials of streptokinase and heparin in phlebographically documented acute deep venous thrombosis. Am J Med. 1984;76:393–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90656-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bounameaux H, Banga JD, Bluhmki E, Coccheri S, Fiessinger JN, Haarmann W, et al. Double-blind, randomized comparison of systemic continuous infusion of 0.25 versus 0.50 mg/kg/24 h of alteplase over 3 to 7 days for treatment of deep venous thrombosis in heparinized patients: Results of the European Thrombolysis with rt-PA in Venous Thrombosis (ETTT) trial. Thromb Haemost. 1992;67:306–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Francis CW, Totterman S. Magnetic resonance imaging of deep vein thrombi correlates with response to thrombolytic therapy. Thromb Haemost. 1995;73:386–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Protack CD, Bakken AM, Patel N, Saad WE, Waldman DL, Davies MG. Long-term outcomes of catheter directed thrombolysis for lower extremity deep venous thrombosis without prophylactic inferior vena cava filter placement. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:992–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Enden T, Klow NE, Sandvik L, Slagsvold CE, Ghanima W, Hafsahl G, et al. CaVenT study group. Catheter-directed thrombolysis vs. anticoagulant therapy alone in deep vein thrombosis: Results of an open randomized, controlled trial reporting on short-term patency. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:1268–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vik A, Holme PA, Singh K, Dorenberg E, Nordhus KC, Kumar S, et al. Catheter-directed thrombolysis for treatment of deep venous thrombosis in the upper extremities. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;32:980–7. doi: 10.1007/s00270-009-9655-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Segal JB, Streiff MB, Hofmann LV, Thornton K, Bass EB. Management of venous thromboembolism: A systematic review for a practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:211–22. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-3-200702060-00150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meissner MH. Thrombolytic therapy for acute deep vein thrombosis and the venous registry. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2002;3(Suppl 2):s53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mewissen MW. Catheter-directed thrombolysis for lower extremity deep vein thrombosis. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;4:111–4. doi: 10.1016/s1089-2516(01)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grewal NK, Martinez JT, Andrews L, Camerota AJ. Quantity of clot lysed after catheter-directed thrombolysis for iliofemoral deep venous thrombosis correlates with post thrombotic morbidity. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:1209–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim HS, Preece SR, Black JH, Pham LD, Streiff MB. Safety of catheter-directed thrombolysis for deep venous thrombosis in cancer patients. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:388–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Delomez M, Beregi JP, Willoteaux S, Bauchart JJ, d’othee B Janne, Asseman P, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy in patients with deep venous thrombosis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2001;24:42–8. doi: 10.1007/s002700001658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith GJ, Molan MP, Fitt G, Brooks DM. Mechanical thrombectomy in acute venous thrombosis using an Amplatz thrombectomy device. Australas Radiol. 1999;43:456–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1673.1999.00711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tadavarthy SM, Murray PD, Inampudi S, Nazarian GK, Amplatz K. Mechanical thrombectomy with the Amplatz device: Human experience. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1994;5:715–24. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(94)71590-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kasirajan K, Gray B, Ouriel K. Percutaneous AngioJet thrombectomy in the management of extensive deep venous thrombosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:179–85. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61823-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lin PH, Zhou W, Dardik A, Mussa F, Kougias P, Hedayati N, et al. Catheter-direct thrombolysis versus pharmacomechanical thrombectomy for treatment of symptomatic lower extremity deep venous thrombosis. Am J Surg. 2006;192:782–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ferris EJ, Lim WN, Smith PL, Casali R. May-Thurner syndrome. Radiology. 1983;147:29–31. doi: 10.1148/radiology.147.1.6828755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patel NH, Stookey KR, Ketcham DB, Cragg AH. Endovascular management of acute extensive iliofemoral deep venous thrombosis caused by May-Thurner syndrome. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11:1297–302. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lamont JP, Pearl GJ, Patetsios P, Warner MT, Gable DR, Garett W, et al. Prospective evaluation of endoluminal venous stents in the treatment of the May-Thurner syndrome. Ann Vasc Surg. 2002;16:61–4. doi: 10.1007/s10016-001-0143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]