Abstract

The role of music in intensive care medicine is still unclear. However, it is well known that music may not only improve quality of life but also effect changes in heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV). Reactions to music are considered subjective, but studies suggest that cardio/cerebrovascular variables are influenced under different circumstances. It has been shown that cerebral flow was significantly lower when listening to “Va pensioero” from Verdi's “Nabucco” (70.4+3.3 cm/s) compared to “Libiam nei lieti calici” from Verdi's “La Traviata” (70.2+3.1 cm/s) (P<0,02) or Bach's Cantata No. 169 “Gott soll allein mein Herze haben” (70.9+2.9 cm/s) (P<0,02). There was no significant influence on cerebral flow in Beethoven's Ninth Symphony during rest (67.6+3.3 cm/s) or music (69.4+3.1 cm/s). It was reported that relaxing music plays an important role in intensive care medicine. Music significantly decreases the level of anxiety for patients in a preoperative setting (STAI-X-1 score 34) to a greater extent even than orally administered midazolam (STAI-X-1 score 36) (P<0.001). In addition, the score was better after surgery in the music group (STAI-X-1 score 30) compared to midazolam (STAI-X-1 score 34) (P<0.001). Higher effectiveness and absence of apparent adverse effects make relaxing, preoperative music a useful alternative to midazolam. In addition, there is sufficient practical evidence of stress reduction suggesting that a proposed regimen of listening to music while resting in bed after open-heart surgery is important in clinical use. After 30 min of bed rest, there was a significant difference in cortisol levels between the music (484.4 mmol/l) and the non-music group (618.8 mmol/l) (P<0.02). Vocal and orchestral music produces significantly better correlations between cardiovascular and respiratory signals in contrast to uniform emphasis (P<0.05). The most benefit on health in intensive care medicine patients is visible in classical (Bach, Mozart or Italian composers) music and meditation music, whereas heavy metal music or techno are not only ineffective but possibly dangerous and can lead to stress and/or life-threatening arrhythmias, particularly in intensive care medicine patients.

Keywords: Bach, classic music, intensive care medicine, music performance, music perception, music therapy, mozart

INTRODUCTION

It has been reported that music showed consistent physiological responses with different styles in most subjects, in whom responses were related to tempo and were associated with faster breathing.[1–3] The responses were qualitatively similar in musicians and nonmusicians and apparently were not influenced by musical preferences although musicians did respond more. In recent years, music has been increasingly used as a therapeutic tool in the treatment of different diseases and in intensive care medicine.[4–6] However, the physiological basis of music therapy is not well understood even in normal subjects. The purpose of the present manuscript is to summarize the different effects of music on physiological parameters and to describe what kind of music is helpful in intensive care medicine patients and what kind of music is probably dangerous for them.

EFFECTS OF MUSIC ON HEALTH

It is well known that music can evoke emotional responses that improve quality of life but by the same token they can also induce stress and aggressiveness.[7] Music may enhance positive or calming emotions and play an important role in the “making of health” throughout human history through its use in rituals and religious services. Music improves concentration but has different neurophysiological aspects, the effectiveness of which is governed by individual preferences. The role of music correlates with music profiles and continuous “mirroring” of music profiles appears to be present in all subjects, regardless of musical training, practice, or personal taste, even in the absence of accompanying emotions. The ability of music to increase physical work activity has been documented for 2,800 years. In Ancient Greece, the kithara (κıθάρα – a harp-like instrument held on the lap) and flute music was played during the Olympic Games with the goal of improving sporting activities. It has been shown that this led to better athletic performances (improvement about 15%). In addition, the effect of music is not only well known on exercise training but music therapy is increasingly used in different disciplines, from neurological disease to intensive care and palliative medicine.[8] However, many questions remain unanswered: Does music make (only) happy and/or will improve health? What are the mechanisms of music? Is it possible to regard music as a “drug” for treatment? What effects does music have on cardiovascular, respiratory, or brain-area systems? Is there an “ideal” music for everybody?

BRAIN AND MUSIC

The human brain is divided into two hemispheres, and the right hemisphere has been traditionally identified as the seat of music appreciation. However, no one has found a “musical center” there, or anywhere else. Studies of musical understanding in people who have damage to either hemisphere, as well as brain scans of people taken while listening to music, have reveal that music perception emerges from the interplay of activity in both sides of the brain.[3] Some brain circuits respond specifically to music; but, as you would expect, parts of these circuits participate in other forms of sound processing. For example, the region of the brain dedicated to perfect pitch is also involved in speech perception. Music and other sounds entering the ears travel to the auditory cortex, assemblages of cells just above both ears. The right side of the cortex is crucial for perceiving pitch as well as certain aspects of melody, harmony, timbre, and rhythm.[2] The left side of the brain in most people excels at processing rapid changes in frequency and intensity, both in music and words. Both left and right sides are necessary for complete perception of rhythm. The frontal cortex of the brain, where working memories are stored, also plays a role in rhythm and melody perception. Other areas of the brain deal with emotion and pleasure. The power of music to affect memory is quite intriguing. Mozart's music and baroque music, with a 60 beats per minute beat pattern, activate the left and right brain. The simultaneous left and right brain action maximizes learning and retention of information. The information being studied activates the left brain while the music activates the right brain. Also, activities which engage both sides of the brain at the same time, such as playing an instrument or singing, cause the brain to become more capable of processing information

HEART AND MUSIC

Cardiovascular diseases are present in many intensive care medicine patients, particularly patients with an acute myocardial infarction and/or life threatening ventricular tachyarrhythmias. In addition there are intensive care medicine patients prior to or after cardiac surgery. Therefore, music may play an important role in patients with underlying heart disease. Recently, interest has developed in the cardiovascular, respiratory, and neurophysiological effects of listening to music, including the brain areas involved, which appear to be similar to those involved in arousal. Bernardi et al.[9] studied 24 young, healthy subjects (12 chorists and 12 nonmusician control subjects) who listened in random order to music with vocal (Puccini's “Turandot”) or orchestral (Beethoven's Ninth Symphony adagio) progressive crescendos, more uniform emphasis (Bach's Cantata BWV 169 “Gott soll allein mein Herz haben”), 10-second period rhythmic phrases (Verdi's arias “Va pensiero” and “Libiam nei lieti calci”) or silence while heart rate, respiration, blood pressure, middle cerebral artery flow velocity, and skin vasomotion were recorded. Vocal and orchestral crescendos produced significant correlations between cardiovascular or respiratory signals and musical profile, particularly skin vasoconstriction and blood pressures, proportional to crescendo, in contrast to uniform emphasis, which induced skin vasodilation and reduction in blood pressure (P<0.05). Correlations were significant both in individual and group-averaged signals (P<0.05). Phrases at 10-s intervals by Verdi entrained the cardiovascular autonomic variables. It is important to note that no qualitative differences were observed in recorded measurements between musicians and non-musicians.[9] In this study cerebral flow was significantly lower when listening to “Va pensioero” (70.4+3.3 cm/s) compared to “Libiam nei lieti calici (70.2+3.1 cm/s) (P<0,02) or Bach (70.9+2.9 cm/s) (P<0,02). There was no significant influence on cerebral flow in Beethoven's Ninth Symphony during rest (67.6+3.3 cm/s) or music (69.4+3.1 cm/s). Grewe et al.[10] observed that some subjects occasionally experienced the sensation of chills during sudden crescendi, together with cardiovascular changes. It has been shown in other studies by Yoshie et al.[11] and Nakahara et al.[12] that music will have beneficial effects on heart rate, heart rate variability, and anxiety levels in not only skilled pianists but also non-musicians during both performance of and listening to music. The findings of these studies suggest, though, that musical performance has a greater effect on emotion-related modulation in cardiac autonomic nerve activity than musical perception.[13,14] Other studies reported significant decreases in heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory volume, oxygen saturation, catecholamines, cortisol, and basal state when listening to music compared to controls.[1]

CARDIAC SURGERY AND MUSIC

There are many patients in intensive care units prior to and after cardiac surgery. Therefore, it is of interest whether music has beneficial effects in these patients or not. Recently, several studies have analyzed the effect of music prior to and after cardiac surgery and during rehabilitation.[3,4] The influence of music was studied prior to bypass grafting or valve replacement in 372 patients wherein a portion of the group received midazolam (0.05-0.1 mg/kg) according to the STAI-X-1 anxiety score.[14] Of the 372 total patients, there were 177 patients who had music prior to surgery and 195 patients who received midazolam. There were significant differences in the anxiety scores prior to and after surgery between both groups: In the “music group” prior to and after surgery the score was 34 and 36, respectively, whereas the score was 30 and 34 in the midazolam group (P<0.001). Nilsson et al.[15] analyzed 40 patients who underwent bypass grafting or aortic valve replacement and in these patients oxytocin, heart rate, blood pressure, PaO2 and oxygen saturation SaO2 were studied in two groups: One group had music, the other group served as controls. As pointed out by the authors there were significantly better values of oxytocin (increased) and PaO2 (increased) in the music group compared to controls (P<0.05). No significant differences were observed regarding heart rate, blood pressure, and SaO2. In another study, Nilsson et al.[16] analyzed the follow-up of 58 patients after cardiac surgery. These patients underwent musical therapy (30 min music exposure one day after surgery) compared to controls. Evaluation of cortisol, heart rate, ventilation, blood pressure, SaO2, pain, and anxiety indices was performed. There were significantly lower cortisol levels in the music group (484.4 mmol/l) compared to patients without music (618.8 mmol/l) (P<0.02). There were no significant differences in heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, and oxygen saturation between both groups. Similar effects have been reported by Antonietti in patients who underwent rehabilitation after surgery.[17]

INTENSIVE CARE AND MUSIC

Music plays an important role in intensive care medicine.[18] It is well known that soft and not loud sounds have beneficial effects on patients while treated in intensive care medicine and will reduce pain and stress significantly. Soft, silent, or quiet classical or mediation music is associated with the reduced need for sedative drugs and reduced perception of pain. Despite the well-known effects of music in intensive care medicine this kind of “therapy” is observed rarely in daily practice. In addition to this, there are many psychological effects: Music from the youth of the patient will lead to improved mood, concentration, and motivation, all of which are essential for the intensive care patient.[3,4] There are spectacular effects of music in geriatric patients while in intensive care units: Music from the youth and music from “better days” will lead to improved mood, motivation, increased vitality, and will also encourage social contacts. This is important in patients with depressive syndromes. Chan et al.[13] performed a randomized study in 47 people under the age of 65 who underwent music therapy compared to 24 controls. In the music group, there were statistically significant decreases in depression scores (P<0.001), blood pressure (P<0.001), and heart rate (P<0.001) after 1 month (P<0.001). The implication of this observation is that music can be an effective intervention for older and/or patients suffering depressive syndromes. We all know that the terminal patient presents a unique situation, particularly in intensive care medicine. It has been reported that these patients will continue hearing although some other organ functions have been lost.[5] Therefore, music plays an important role in this situation and music from the patient's youth has the most impact.[19,20] This music might prove to be the last source of aesthetic enjoyment and simple happiness for the dying patient. Therefore, these observations support the important role of music in intensive care medicine.

CHOOSING APPROPRIATE MUSIC FOR THE INTENSIVE CARE PATIENT

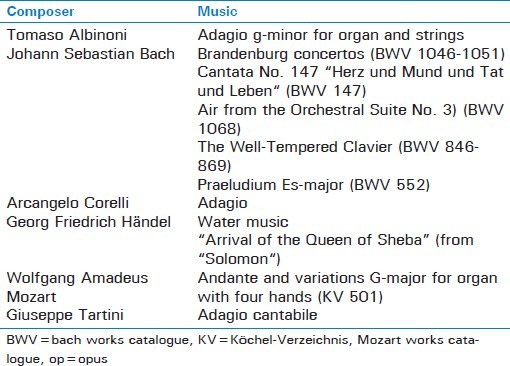

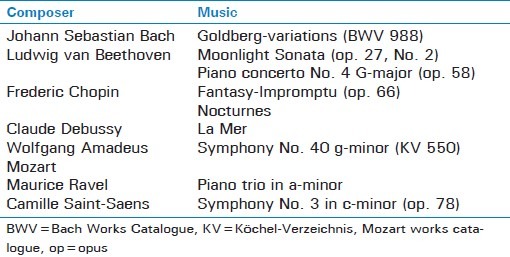

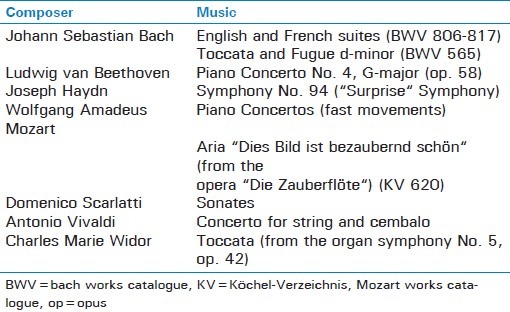

The most beneficial music for the health of a patient is classical music, which holds an important role in music therapy.[3,4] It has been shown that music composed by Bach, Mozart, and Italian composers is the most powerful in “treating” patients It is possible to select the “ideal” therapy for cardiovascular disturbances, recreation, and refreshment of the immune system, improvement of concentration and help with depression [Tables 1–3]. Patients who would receive the most benefit from classical music include those with anxiety, depressive syndromes, cardiovascular disturbances, and those suffering from pain, stress, or sleep disturbances. Many of them were treated on intensive care units’ Popular music is an “eye-opener.” This music incorporates harmonic melodies that will lead to buoyant spirit, good mood leading to lift in mood, increased motivation, and general stimulation. Meditation music has sedative effects. Sounds are slow and rhythms few. This music has beneficial effects in intensive care units and patients who were treated there. Heavy metal and techno are ineffective or even dangerous in intensive care medicine. This music encourages rage, disappointment, and aggressive behavior while causing both heart rate and blood pressure to increase. This music should not be used in intensive care medicine. Hip Hop and Rap are less frequently effective due to the sounds, but can often have effect due to their words – the important element of which is the rhyme structure. Jazz appeals to all senses, but a high degree of concentration is necessary when listening to Jazz. There are few studies of the effect of Jazz on health; due to all observations Jazz is not acceptable for the intensive care patient. Schlager music are songs to sing alone with, have simple structures but frequently have “earworm-character”. This kind of music is inappropriate for influencing health and inappropriate for intensive care medicine.[4]

Table 1.

Effect of classic music in cardiovascular disturbances

Table 3.

Effect of classic music on recreation and refreshment of the immune system

Table 2.

Effect of classical music on improvement of concentration and help with depression

CONCLUSIONS

Music is a combination of frequency, beat, density, tone, rhythm, repetition, loudness, and lyrics. Music influences our emotions because it takes the place of and extends our languages. Research conducted over the past 10 years has demonstrated that persistent negative emotional experiences or an obsession and preoccupation with negative emotional states can increase one's likelihood of acquiring the common cold, other viral infections, yeast infestations, hypersensitivities, heart attacks, high blood pressure, and other diseases. For better personal health, we can then choose “healthful” music and learn to let ourselves benefit from it. The most benefit from music on health and therefore on the intensive care patient is seen in classical and in mediation music, whereas heavy metal or techno are ineffective or even dangerous. There are many composers that effectively improve health, particularly Bach, Mozart, or Italian composers. Various studies suggested that this music has significant effects on the cardiovascular system and influences significantly heart rate, heart rate variability, and blood pressure as well. This kind of music is effective and can be utilized as an effective intervention in patients with cardiovascular disturbances, pain, and in intensive care medicine.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kemper KJ, Danhauer SC. Music as therapy. South Med J. 2005;98:282–8. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000154773.11986.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilkins MK, Morre ML. Music intervention in the intensive care unit: A complementary therapy to improve patient outcomes. Evid Based Nurs. 2004;7:103–4. doi: 10.1136/ebn.7.4.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trappe HJ. The effects of music on the cardiovascular system and cardiovascular health. Heart. 2010;96:1868–71. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.209858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshie M, Kudo K, Ohtsuki T. Motor/autonomic stress responses in a competitive piano performance. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2009;1169:368–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mansky PJ, Wallerstedt DB. Complementary medicine in palliative care and cancer management. Cancer J. 2006;12:425–31. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200609000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Forsblom A, Soinila S, Mikkonen M, et al. Music listening enhances cognitive recovery and mood after middle cerebral artery stroke. Brain. 2008;131:866–76. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krout RE. Music therapy with imminently dying hospice patients and their families: Facilitating release near the time of death. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2003;20:129–34. doi: 10.1177/104990910302000211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mramor KM. Music therapy with persons who are indigent and terminally ill. J palliative Care. 2001;17:182–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernardi L, Porta C, Casucci G, Balsamo R, Bernardi NF, Fogari R, et al. Dynamic interactions between musical, cardiovascular, and cerebral rhythms in humans. Circulation. 2009;30(119):3171–80. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.108.806174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grewe O, Nagel F, Kopiez R, Altenmüller E. How does music arouse “chills”? Investigating strong emotions, combining psychological, physiological, and psychoacoustical methods. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1060:446–9. doi: 10.1196/annals.1360.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshie M, Kudo K, Murakoshi T, Ohtsuki T. Music performance anxiety in skilled pianists: Effects of social-evalutive performance situation on subjective, autonomic, and electromyographic reactions. Exp Brain Res. 2009;199:117–26. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1979-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakahara H, Furuya S, Obata S, Masuko T, Kinoshita H. Emotion-related changes in heart rate and its variability during performance and perception of music. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2009;1169:359–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan MF, Chan EA, Mok E, Kwan Tse FY. Effect of music on depression levels and physiological responses in community-based older adults. Int J Health Nurse. 2009;18:285–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2009.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bringman H, Giesecke K, Thörne A, Bringman S. Relaxing music as pre-medication before surgery: A randomised controlled trial. Acta Anaestesiol Scand. 2009;53:759–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.01969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nilsson U. The effect of music intervention in stress response to cardiac surgery in a randomized clinical trial. Heart Lung. 2009;38:201–7. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nilsson U. Soothing music can increase oxytocin levels during bed rest after open-heart surgery: A randomized control trial. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:2153–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antonietti A. Why is music effective in rehabilitation? Stud Health Technol Inform. 2009;145:179–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan MF, Chung YF, Chung SW, Lee OK. Investigating the physiological responses of patients listening to music in the intensive care unit. J Clinical Nurs. 2009;18:1250–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silverman MJ. The effect of single-session psychoeducational music therapy on verbalizations and perceptions in psychiatric patients. J Music Therapy. 2009;46:105–131. doi: 10.1093/jmt/46.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freeman L, Caserta M, Lund D, Rossa S, Dowdy A, Partenheimer A. Music thanatology: Prescriptive harp music as palliative care for the dying patient. Am J of Hosp Palliat Care. 2006;23:100–4. doi: 10.1177/104990910602300206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]