Abstract

Background and Aim:

Maxillofacial trauma is frequently encountered in the Accident and Emergency department of hospitals either as an isolated injury or as a part of multiple injuries to the head, neck, chest, and abdomen. This study aimed to assess retrospectively the profile of maxillofacial injuries in patients reporting to a tertiary care hospital in East Delhi.

Materials and Methods:

The study was conducted in the Department of Dentistry, UCMS and GTB Hospital, Delhi. Dental case record sheets of 1000 medicolegal cases reporting to the hospital emergency were scrutinized and various demographic and epidemiologic factors, including the patient's age and gender, time and day of reporting, and the etiology and nature of injury were recorded.

Results:

The peak incidence of maxillofacial injury was observed in the age group of 21–30 years, with males outnumbering females in all age groups. Maximum number of trauma cases reported in late evening hours, especially on weekends. Interpersonal assault was the primary etiological factor followed by road traffic accidents. Soft tissue injuries were very common and maxillofacial fractures, when present, were most frequently observed in the mandible followed by the midface.

Conclusion:

The changing trend of the etiology of maxillofacial injuries in East Delhi necessitates strict legislation against violence and education in alcohol abuse. Periodic review of driving skills and stricter implementation of traffic rules in this area is a must to minimize the physical, psychological, and emotional distress associated with maxillofacial trauma.

Keywords: Interpersonal assault, maxillofacial trauma, retrospective analysis

INTRODUCTION

The human face often constitutes the first point of contact in various human interactions and is frequently the preferred target for blows in assault cases. Maxillofacial trauma is thus a common presentation in Accident and Emergency departments of hospitals either as an isolated injury or as a part of multiple injuries to the head, neck, chest, and abdomen. These injuries may cause serious functional, psychological, physical, and cosmetic disabilities.

The etiology of maxillofacial trauma varies from one geographical region to another and even within the same region depending on the prevailing socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental factors. The severity of injury may vary from simple soft tissue lacerations to more complicated fractures of the maxillofacial skeleton. Patients may also possess other associated injuries and often need to be treated with the active participation of the neurosurgeon, ophthalmologist, or the orthopedic surgeon.

The aim of the present study was to assess retrospectively the profile of maxillofacial injuries among patients reporting to a tertiary care hospital in East Delhi. Clearer insight into the etiologic, epidemiologic, and demographic factors related to maxillofacial trauma would help prepare more reliable preventive and health care measures for such cases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted in the Department of Dentistry, University College of Medical Sciences and Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, Delhi, India. This hospital is the main referral government hospital in East Delhi and caters to all kinds of referred emergency cases. The basis of the study was the data obtained from dental case record sheets of 1000 medico legal cases who reported to the hospital emergency during the period from March 2008 till February 2009. Following due clearance from a departmentally instituted ethical committee, the case sheets were thoroughly scrutinized and various demographic, epidemiologic, and pathologic factors, such as the patient's age and gender, the time of reporting, day of reporting, etiology of injury, and the nature of injury, were recorded in specially designed proformas. The data obtained were statistically analyzed and following preliminary inspection and content analysis, the data were interpreted using percentages wherever necessary.

RESULTS

Demographic profile

Age distribution

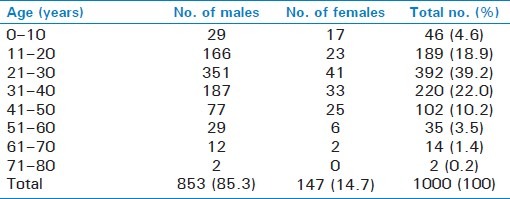

The age of the patients ranged from 1.5 to 78 years with a mean age of 37.4 years. Among these, the majority of cases (>60.0%) were in the second or third decade of their life, with a peak incidence of maxillofacial trauma observed in the age group of 21–30 years. A decreasing trend was seen with age proceeding to both the extremes [Table 1].

Table 1.

Age and gender distribution of patients

Gender distribution

There was male preponderance in the sample with an overall male:female ratio of 5.8:1. Males comprised more than 85.0% of the patients and outnumbered females in each of the age groups [Table 1].

Time of reporting

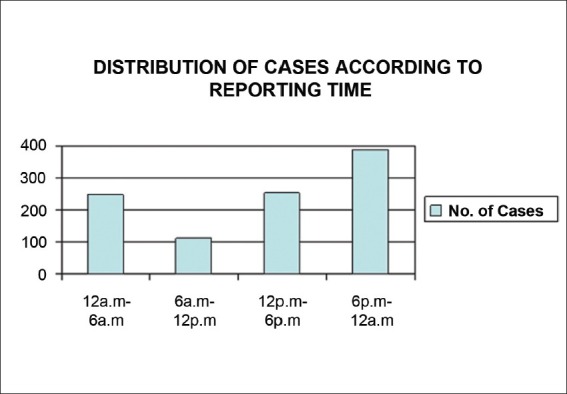

The greatest incidence of maxillofacial trauma was observed in the evening hours between 6 pm and 12 am. The proportion of cases reporting between 12 am and 6 am and between 12 pm and 6 pm was relatively similar, with the least number of cases reporting in the morning (6 am–12 pm) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Graph showing the number of cases reporting at different times of the day

Day of reporting

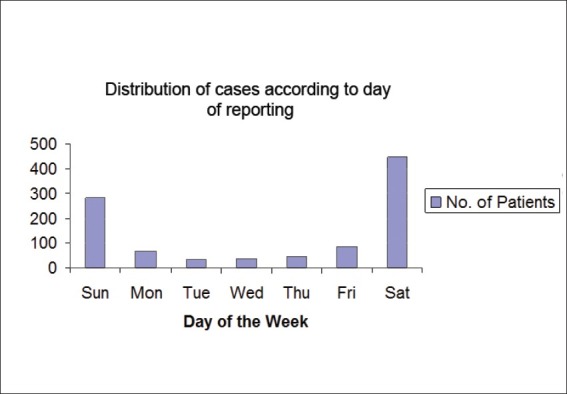

Greatest number of maxillofacial injuries were reported on Saturdays (44.7%) followed by Sundays (28.3%) and Fridays (8.7%). On other days of the week, the relative incidence of maxillofacial trauma was much lesser, with only 6.8% on the injuries reported on Mondays, 3.4% on Tuesdays, 3.6% on Wednesdays, and 4.5 % of maxillofacial trauma cases reported on Thursdays [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Graph showing the number of cases reporting on different days of the week

Etiology of injury

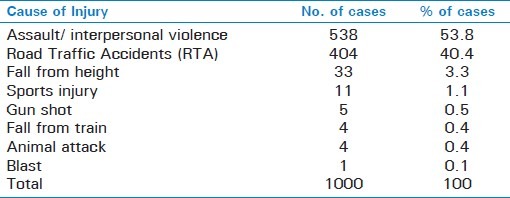

Interpersonal assault was found to be the primary etiologic factor, accounting for approximately 54.0% of the injuries, followed by Road Traffic Accident (40.0%). Other causative factors included falls from height, sport-related injuries, gunshots, animal attacks, and fall from train. One of the patients was a blast victim [Table 2].

Table 2.

No. of injuries caused by various etiological factors

Nature of injury

Analysis of the dental record sheets revealed that patients presented with varying types of maxillofacial injuries. Soft tissue injury was the most frequent injury and was observed in 84.0% of the cases. Contusions (43.2%) and abrasions (38.6%) were the most frequent types of injuries followed by lacerations (18.2%). The lower lip was the most frequent site of trauma followed by the upper lip, gingiva, buccal mucosa, palate, and tongue.

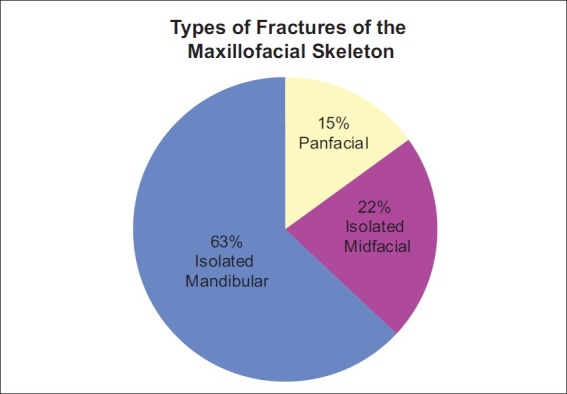

22.5% of patients demonstrated associated dentoalveolar fractures (tooth fracture and/or avulsion) and another 18.0% demonstrated bony fractures. Among patients with maxillofacial skeletal fractures, the mandible was the most frequently fractured bone (in 63.0% cases) followed by the midface (22.0%), while the remaining 15.0% cases demonstrated panfacial fractures [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Pie diagram showing the different types of maxillofacial fractures

DISCUSSION

The effectiveness of various preventive and educational programs with respect to maxillofacial trauma may be reflected through continuing audit of the pattern of such trauma in different parts of the world. Considerable variation has been reported in the profile of facial injuries with respect to the geographical location, socioeconomic status, and cultural background. The present study was conducted to retrospectively assess the profile of maxillofacial trauma in East Delhi and various epidemiologic factors, including the patient's demographic profile, the time and day of reporting, etiology of injury, and the type of maxillofacial injury were assessed.

The pattern of age distribution in maxillofacial injuries demonstrated that people of all ages were affected; the peak incidence was, however, observed in the age group of 21–30 years. This finding is in accordance with a number of previous studies in India[1,2] as well as other parts of the world.[3,4] The third decade is perhaps the most active period of life in which people tend to remain outdoors in search of their livelihood and are thus more vulnerable to vehicular accidents, falls, and assault-related injuries. Individuals in the extremes of life were found to be least affected and most of the injuries (75.7%) were observed in persons of working age group (21–60 years).

The gender distribution revealed a male preponderance in all the age groups as has been reported in other studies. The male:female ratio in our sample (5.8:1) was, however, higher than what has been reported by Ugboko et al.,[4] Jerius,[5] and El-Sheikh et al.,[6] and other authors. This is most likely due to the fact that in the lower socioeconomic group, which constitutes the bulk of the patients reporting to this particular hospital, men are often the primary bread winners of the family and tend to remain outdoors for a large period of time, thus making them susceptible to trauma in general and maxillofacial trauma in particular. Also, females drive less frequently and are thus less likely to be involved in vehicular accidents. They are also less vulnerable to sport-related injuries and to falls and violence related to alcohol consumption. Most of the male patients in the study were young adults who are often injured away from home, whereas female victims are more likely to be assaulted in their homes by someone whom they know.[7]

The greatest incidence of maxillofacial trauma (38.0%) was observed in the evening hours between 6 pm and 12 am. This finding is in accordance with those of Veeresha et al.,[8] and may be attributed to the substantial increase in traffic after the office hours, when people are returning home, and to a tendency to consume alcohol in the evenings. The proportion of cases reporting between 2 am and 6 am and between 12 pm and 6 pm was similar, with the least number of cases reporting in the morning (6 am–12 pm).

An analysis of the day of reporting revealed that the maximum number of facial injuries occurred on Saturdays followed by Sundays. The incidence of maxillofacial trauma on other days of the week was much lesser. A similar increase in assault-related head injuries on weekends has been reported by Shephard et al.,[9] and also by Gilthorpe et al.,[10] and is believed to be associated with increased alcohol consumption and late night partying on these days. Greater incidence of trauma in this region on weekends may also be accredited to the fact that this hospital is situated close to the main highway (GT Road) and on weekends, the traffic restrictions imposed on heavy vehicles are lifted, thus increasing the chances of road traffic accidents. Stricter governance of vehicular traffic in this area, particularly on weekends is thus of prime importance.

The etiology of maxillofacial injuries is known to vary from one geographical region to another. In developing countries, such as ours, road traffic accident is generally believed to be the most common cause of facial trauma[11] and this has been confirmed by some of the previous studies.[2,12,13] In the present study, however, interpersonal assault was found to be the most common etiology behind maxillofacial injuries. Our contradictory finding signifies the changing trend of etiology of maxillofacial trauma in East Delhi and may be attributed to the fact that this hospital is largely attended by the relatively poor immigrant population from across the state border. Two factors have been consistently associated with facial injury due to alleged assaults, namely alcohol and unemployment.[14,15] Unemployment and the associated frustration and rage, particularly in youth of lower socioeconomic group, leads them to consume alcohol and they frequently end up in arguments and brawls, leading to violence. Clearly, the face is the preferred “target” for blows during an assault.

Road Traffic Accident constituted the second most common causative factor. It has been reported that in automobile accidents, the facial area is the most frequently injured region,[16] with 20%–60% of all persons involved in automobile collisions having some sort of facial fracture. Delhi, being a metropolitan city, has witnessed vast infrastructural growth in the recent past with a rapid increase in the vehicular traffic and a steady rise in the immigrant population. Vehicular accidents in this part of Delhi may be accredited to the nonsegregation of slow and fast moving traffic in this region, overloaded buses, and the proximity to national highway.

Other etiologic factors reported in this study include falls from height and sport-related injuries (both of which were more common in children) and animal attacks, gunshots, and blasts. It is common for people in this part of the country to sleep on rooftops, especially during the summer months. A large proportion of the fall victims were children who had fallen from height while playing or flying kites on flat rooftops .

The most common type of maxillofacial injury was found to be soft tissue trauma . This finding is in accordance with that of Gassner et al.,[17] who demonstrated a very high frequency of soft tissue injuries in their comprehensive review of cranio-maxillofacial trauma and also with those of Le et al.,[18] who reported that soft tissue injuries were the most common type of injuries in cases reporting with domestic violence. The fact that the most common etiologic factor in the present study was interpersonal assault may contribute to the high incidence of soft tissue injuries, which has been reported here. Similar results have also been reported by Rana et al.[19] in adults and by Okoje[20] in pediatric patients.

Facial contusions and abrasions were the most frequent types of soft tissue injuries followed by lacerations. Previous studies on maxillofacial injuries associated with interpersonal violence have reported contusions and abrasions to be a frequent occurrence,[18,21] while lacerations have been reported more frequently in severe trauma episodes resulting from traffic accidents and gun shot injuries.[20]

Lacerations when present, were most frequently observed extraorally on the lower and upper lips and intraorally on the gingival mucosa followed by buccal mucosa, palate, and tongue, a finding which is in accordance with those of Gassner et al.[17]

The incidence of dentoalveolar trauma and associated tooth fractures or avulsion was also significant. Among bony fractures, the mandible was the most frequently fractured bone. This finding is in accordance with those of Lida et al.[22] in Japan, Motamedi[23] in Iran, and of Erol et al.[24] in Turkey. The high incidence of isolated mandibular fractures in studies all across the world may be attributed to the prominence of the lower jaw and to its exposed anatomical position on the face. The mandibular condyle is a relatively weak anatomic area, which often gets fractured following a blow to the chin as the force of the blow is transferred through the mandibular body onto the condyle. Also, the abrupt change in direction in the region of the angle of the mandible (from a relatively thicker body to a comparably thin ramus) also increases the chances of mandibular fracture following facial trauma. The midfacial skeleton was another frequent site of fracture in this study. Le et al.[18] believe that the midfacial skeleton, especially the nasal bone stands a high risk of fracture following trauma due to its relative structural weakness and prominent location on the face.

Various epidemiologic and demographic characteristics of facial injuries have been highlighted in this study. This is perhaps the first study in East Delhi which assesses the profile of maxillofacial trauma in this region. More elaborate prospective surveys may further corroborate the findings of our study and help prepare more reliable preventive and health care measures against maxillofacial trauma.

CONCLUSION

The maxillofacial skeleton is especially prone to traumatic injuries. The changing trend of etiology of maxillofacial injuries in East Delhi, particularly the alarming increase in assault, necessitates strict legislation against violence by prohibiting easy access to dangerous weapons and by education in alcohol abuse. Provision of pedestrian friendly paths, segregation of heavy and light motor vehicles and strict governance of traffic by authorities, especially during late evening hours and on weekends is a must to minimize the physical, psychological, and emotional distress associated with trauma in general and maxillofacial trauma in particular. The high incidence of maxillofacial injuries also has implication for the establishment of dedicated maxillofacial units in district general hospitals and in regional or supraregional trauma units.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Subhashraj K, Nandakumar N, Ravichandran C. Review of maxillofacial injuries in Chennai, India: A study of 2748 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;45:637–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandra-Shekhar BR, Reddy CV. A five- year retrospective statistical analysis of maxillofacial injuries in patients admitted and treated at two hospitals of Mysore city. Indian J Dent Res. 2008;19:304–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.44532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zargar M, Khaji A, Karbakhsh M, Zarei MR. Epidemiology study of facial injuries during 13 months of trauma registry in Tehran. Indian J Med Sci. 2004;58:109–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ugboko VI, Odusanya SA, Fagade OO. Maxillofacial fractures in a semi-urban Nigerian teaching hospital. A review of 442 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;27:286–9. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80616-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jerius MY. The etiology and patterns of maxillofacial injuries at a military hospital in Jordan. Middle East J Fam Med. 2008;6:31–3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Sheikh MH, Bhoyar SC, Emsalam RA. Mandibular fractures in Benghazi Libya: A retrospective analysis. J Indian Dent Assoc. 1992;63:367–70. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zachariades N, Koumoura F, Konsolaki-Agouridaki E. Facial trauma in women resulting from violence by men. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:1250–3. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90476-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veeresha KL, Shankararadhya MR. Analysis of fractured mandible and fractured middle third of the face in road traffic accidents. J Indian Dent Assoc. 1987;59:150–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shepherd JP, Al-Kotany MY, Subadan C, Scully C. Assault and facial soft tissue injuries. Br J Plast Surg. 1987;40:614–9. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(87)90157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilthorpe MS, Wilson RC, Moles DR, Bedi S. Variations in admissions to hospital for head injury and assault to the head Part 1: Age and gender. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;37:294–300. doi: 10.1054/bjom.1998.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown RD, Cowpe JG. Patterns of maxillofacial trauma in two different cultures. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1985;30:299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subhashraj K, Ravichandran C. A 4-year retrospective study of mandibular fractures in a South Indian city. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:77–80. doi: 10.1097/scs.0b013e318069005d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sawhney P, Ahuja RB. Faciomaxillary fractures in North India: A statistical analysis and review of management. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;26:430–4. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(88)90097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Telfer MR, Jones GM, Shepherd JP. Trends in the aetiology of maxillofacial fractures in the United Kingdom (1977-1987) Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;29:250–5. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(91)90192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magennis P, Shepherd J, Hutchison I, Brown A. Trends of facial injuries: Increasing violence more than compensates for decreasing road trauma. Br Med J. 1998;316:325–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huelke DF, Compton CP. Facial injuries in automobile crashes. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983;41:241–4. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(83)90266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gassner R, Tuli T, Hachl O, Rudisch A, Ulmer H. Craniomaxillofacial trauma: A 10 year review of 9,543 cases with 21,067 injuries. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2003;31:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(02)00168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le BT, Dierks EJ, Ueeck AU, Homer LD, Potter BF. Maxillofacial injuries associated with domestic violence. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:1277–83. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.27490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rana ZA, Khoso NA, Arshad O, Siddiqi KM. An Assessment of maxillofacial injuries: A 5-year study of 2112 patients. Ann Pak Inst Med Sci. 2010;6:113–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okoje VN, Alonge TO, Oluteye OA, Denloye OO. Changing pattern of pediatric maxillofacial injuries at the accident and emergency department of the University Teaching Hospital, Ibadan: A four-year experience. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2010;25:68–71. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x0000769x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saddki N, Suhaimi AA, Daud R. Maxillofacial injuries associated with intimate partner violence in women. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:268–73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lida S, Kogo M, Sugiura T, Mima T, Matsuya T. Retrospective analysis of 1502 patients with facial fractures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;30:286–90. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2001.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motamedi MH. An assessment of maxillofacial fractures: A 5- year study of 237 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:61–4. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erol B, Tanrikulu R, Gorgun B. Maxillofacial fractures. Analysis of demographic distribution and treatment in 2901 patients (25 year experience) J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2004;32:308–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]