Abstract

Context:

Skin changes in pregnancy can be categorized as 1) physiological/hormonal, 2) alterations in pre-existing skin diseases, or 3) represent development of new dermatoses, some of which may be pregnancy specific.

Case Report

We describe a 19 years old female at 27 weeks gestation who presented with a rash on the face and breast, with intense pruritis. Hematoxylin and eosin demonstrated Scabies mites within the epidermis, with an intense perivascular infiltrate of lymphohistiocytic cells around the superficial dermal blood vessels. By direct immunofluorescence (DIF), human fibrinogen was also detected in the perivascular areas. DIF also revealed deposits of human IgG and complement C5-9/MAC deposits in the sweat glands, as well as in nerves surrounding the sweat glands subjacent to the mites. Overexpression of ezrin and junctional adhesion molecule antibodies close to the scabies infection sites were also seen.

Conclusion:

Given that the hallmark of clinical scabies is intense pruritus and that very limited information is available regarding the pathophysiology of this symptom, we suggest that the itching sensation may be exacerbated by nerves and eccrine sweat glands in close proximity to the sites of infection.

Keywords: Scabies, nerves, sweat glands, complement C5-9/MAC, junctional adhesion molecule (JAM-1), ezrin, glial fibrillary acidic protein

Introduction

Some of the most challenging diagnoses in a dermatology practice include the dermatoses of pregnancy. Pregnancy-specific skin dermatoses include a heterogeneous group of skin eruptions[1]. Some of the most common diseases in this group include 1) the atopic eruption of pregnancy (includes eczema of pregnancy, prurigo of pregnancy and pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy), 2) pemphigoid gestationis (herpes gestationis), 3) intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, 4) impetigo herpetiformis, 5) viral exanthema, 6) pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP) and 7) scabies mite infections[1]. Atopic eruption of pregnancy is the most common of these disorders[1].

In a pregnant female with any dermatosis, a search for scabies mites is indicated if the history and physical examination findings are suggestive. In many dermatoses of pregnancy, skin biopsies for hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) examination and for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) are warranted. DIF results classically differentiate PUPPP from herpes gestations. Specifically, direct immunofluorescence studies are classically negative in PUPPP. In contradistinction, a herpes gestation is a rare autoimmune blistering disease, characterized by linear deposits of Complement/C3 along the basement membrane zone. PUPPP is a benign dermatosis that usually arises late in the third trimester of an initial pregnancy. The entity has been previously reported under other monikers, including 1) toxemic rash of pregnancy, 2) toxemic erythema of pregnancy, and 3) late-onset prurigo of pregnancy[1]. Currently, the appellation polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP) is utilized extensively in Great Britain, while PUPPP is typically used in the United States. Following atopic eruption of pregnancy, which presents earlier in gestation, PUPPP is the second most common dermatosis of pregnancy[1]. PUPPP occurs in 1 out of 160-240 initial pregnancies.

Human scabies is caused by an infestation of the skin by the human scabies mite (Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis)[2]. Scabies is a very contagious skin condition, and afflicts 300 million people worldwide. Scabies has been a scourge among human beings for thousands of years, including worldwide epidemics during warfare, famine and overcrowding[2]. The most common symptoms of scabies are a papular skin rash, and intense pruritis. The scabies mite is spread by direct, prolonged skin-to-skin contact with a person who has scabies, as well as by direct contact with contaminated fomites.

Case Report

We describe a case of scabies infection in a 19 year old Caucasia female at 27 weeks gestation that presented complaining of a two month history of a rash on the breast, face and abdomen with intense itching. No systemic symptoms were described. The physical examination demonstrated an erythematous, papular rash in these areas. No vesicles or bullae were seen. Skin biopsies were obtained for hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) histologic examination, as well as for direct immunofluorescence (DIF). Following the biopsy procedures, 60 mg of prednisone was administered intramuscularly to address the intense itching; all other clinical prenatal tests were normal. Following clinical clearance, no recurrence of the primary rash was appreciated. In addition, no post-scabies eczema was detected.

Routine H & E staining was performed; DIF of four micron thick skin cryosections was also performed, with multiple fluorescein isothiocyanate ( FITC)-conjugated secondary antibodies. We utilized the following antibodies of rabbit origin: 1) anti-human IgG, 2) anti-human IgA, 3) anti-human IgM, 4) anti-human fibrinogen, 5) anti-human albumin, and 6) anti-human C5-9 (membrane attack complex of complement (MAC)), all from Dako (Carpinteria, California, USA). We also utilized 7) anti-human Complement/C1q (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, Alabama, USA). To colocalize the immune response of the patients with neural structures, we stained for 8) anti-human glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), conjugated with Cy3 (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri, USA). We also utilized 9) anti-ezrin and 10) anti-junctional adhesion molecule (JAM-1; also known as platelet adhesion molecule, or CD321 antigen) monoclonal antibodies at 1:50 dilutions (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, California, USA); the secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor® 647-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibodies . The slides were then counterstained with 4’, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Dapi) (Pierce, Rockford, Illinois, USA).

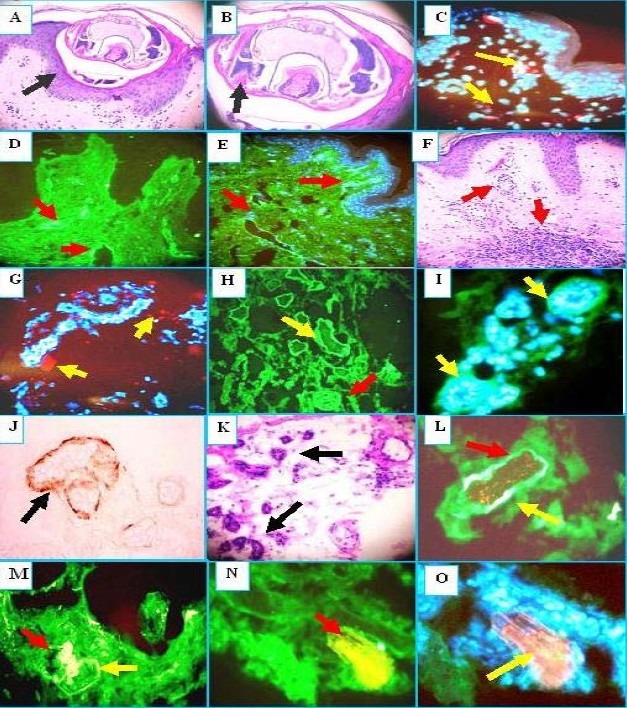

Note H&E sections of Sarcoptes scabei mites, located immediately beneath the stratum corneum of the epidermis (Fig. 1a and b, black arrows) Spongiosis was observed within the epidermal stratum spinosum. A florid, superficial and deep, perivascular dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, eosinophils and neutrophils was present (Fig. 1f, red arrows). Some inflammation and necrosis of some of the eccrine sweat glands was also detected (Fig. 1k, black arrows). Fig. 1 also displays our DIF and IHC results.

Fig. 1.

H & E (a, b, f, k): see Results section for description. DIF (c, d, e, g,h ,i, l, m, n, o). Note that nuclei are counterstained with 4’, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Dapi) on (c, e, g, and o) (blue stain). c. We found some overexpression of ezrin in the epidermal area close where the mite was found in the epidermis (red dot staining) (yellow arrows). d. and e. Positive staining of the superficial and intermediate vessels with antibody to human fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugated fibrinogen (green staining) (red arrows).g we found some overexpression of junctional adhesion molecule (JAM-1) around the inflamed vessels close to the scabies infection site (red dot staining) (yellow arrows). h, i, and l, Note positive staining to the eccrine sweat glands utilizing anti-human FITC conjugated IgG antibody (green staining) (yellow arrows). j Positive immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining to the sweat glands using Complement/C5b-99/MAC) (brown staining) (black arrow). m, n Note autoreactivity to a nerve utilizing the FITC conjugated human albumin antibody (green stain) yellow arrow that colocalize with ppg.9.5 neural marker (yellowish staining) (red arrows. In n, higher magnification. In o, we present the same area as in m and n, but we utilize a Texas red conjugated antibody to human glial fibrillary acidic protein and a FITC conjugated human fibrinogen antibody to confirm the neural nature of this structure. The overlapping of red and green stain shows like a bright pinkish (yellow arrow). The nerve was also located in proximity to the mite.

Discussion

Most skin eruptions of pregnancy resolve postpartum, and require only symptomatic treatment. In our diagnostic process, we rejected incorrect diagnoses utilizing the clinical history, and by our pathology H&E, DIF and IHC studies.

Scabies occurs worldwide, and affects people of all races and social classes. Scabies can spread rapidly under crowded conditions where close body contact is frequent. Institutions such as nursing homes, extended care facilities, child care facilities and prisons are often sites of scabies outbreaks. The microscopic scabies mite burrows into the upper layers of the skin, where it lives and lays its eggs[2]. The scabies mite is almost always transmitted by direct, prolonged, skin-to-skin contact with a person who already is infested. An infested person can spread scabies even if he or she has no symptoms. Humans are the sole source of human scabies infestation; animals do not spread human scabies[1–5].

Selected immunocompromised, elderly, disabled and/or debilitated persons are at risk for a severe form of scabies titled crusted, or Norwegian, scabies[2]. Persons with crusted scabies have thick crusts of skin that contain large numbers of scabies mites and eggs. The mites in crusted (Norwegian) scabies are not more virulent than in non-crusted scabies; however, they are much more numerous (up to 2 million per patient)[2]. Because these patients are infested with such large numbers of mites, persons with crusted (Norwegian) scabies are very contagious to other persons. In addition to spreading scabies through brief, direct skin-to-skin contact, persons with crusted scabies can readily transmit scabies indirectly by shedding mites that contaminate fomites such as clothing, bedding, and furniture[1–5]. Individuals with crusted scabies should receive quick and aggressive medical treatment for their infestation to prevent spread of the disease scabies.

The etiologic agent of scabies is Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis, in the arthropod class Arachnida, subclass Acari, family Sarcoptidae[2]. The mites burrow into the upper layer of the epidermis, but never below the stratum corneum. The burrows appear as tiny, raised, serpentine lines that are grayish or skin-colored and can be a centimeter or more in length. Other variants of scabies mites may cause infestations in other mammals, such as domestic cats, dogs, pigs, and horses[1–5]. Human scabies mites often are found between the fingers and on the wrists[2].

The clinical diagnosis of a scabies infestation is typically based upon the appearance and distribution of the skin rash, and the presence of burrows[2]. Whenever possible, the diagnosis of scabies should be confirmed by identifying the mite, mite eggs or fecal matter (scybala). The mite can be removed from the end of its burrow utilizing the tip of a needle; alternatively, a skin scraping may be performed to evaluate the specimen for these findings. However, a person can still be infested even if mites, eggs, or scybala cannot be found; fewer then 10-15 mites may be present on an infested person who is otherwise healthy[2].

Reviewing the literature, few articles have been published in regard to the pathophysiology of the pruritis in scabies, or addressing the host immune response. Most pruritis pathophysiology studies have been performed in animals. Specifically, some authors have identified antigens of the IgG subclass by immunoblotting (IB) of selected S. scabiei mite extracts[3,4]. IgG-binding proteins were detected with individual sera from 30 hypersensitive and 21 chronically infected pigs. Seven protein bands with molecular weights ranging from 36 to greater than 220 kilodaltons bound strongly with the IgG antibodies. A statistically significant difference exists in the antigenic recognition spectra between hypersensitive and chronically infected pigs; the authors demonstrated such a difference in their data[4]. In Norwegian scabies, a study revealed that skin-homing cytotoxic T cells contribute to an imbalanced inflammatory response in the dermis of several scabies patients. The authors suggested that these T cell findings (in combination with a lack of significant B cell immunologic response) may contribute to the failure of the skin immune system to mount an effective host response, thus resulting in uncontrolled growth of the parasite in the Norwegian clinical presentation[5]. In classic scabies, some authors have reported downregulation of the dermal endothelial immune response, in conjunction with proinflammatory cytokines, histamine and/or lipid-derived mediators[6]. Significantly, few scabies studies have been performed utilizing DIF. One of the few DIF studies of scabies lesions revealed IgM, IgA, C3, and fibrin present in the cornified layer of the epidermis, at the dermal/epidermal junction, and in association with papillary dermal vessels; the authors concluded that their findings support a humoral immune response, specifically secondary to scabetic infestation[5–7]. We detected some overexpression of dermal ezrin proteins; in our case, these proteins represent a family of adaptor proteins likely linking endothelial cell transmembrane proteins to surrounding dermal cells and/or matrix, close to the scabies infection site. The significance of this finding is unknown. We also detected some overexpression of JAM-1 in the vessels in proximity to the mite infestation sites. Junctional adhesion molecule (JAM-1) is present in the tight junctional architecture between adjacent endothelial cells. The significance of this finding is also currently unknown; we could not find any data in the medical literature regarding its significance. Since few studies have documented DIF findings in scabies, we propose that direct immunofluorescence be utilized to investigate additional cases. Further investigation in this area may lead to a more complete understanding of the pathophysiology of the disorder, and allow insights into new therapeutic modalities.

Acknowledgement

Jonathan S. Jones, HT and Lynn Nabers, HT, HTL (ASCP) for excellent technical assistance at Georgia Dermatopathology Associates.

References

- 1.Sachdeva S. The dermatoses of pregnancy. Indian J Dermatol. 2008;53:103–105. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.43203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Link/URL: Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Information about scabies for the public. [Acceded December 16, 2009]. http://www.cdc.gov/scabies/

- 3.Hengge UR, Currie BJ, Jäger G, Lupi O, Schwartz RA. Scabies: a ubiquitous neglected skin disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:769–779. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70654-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rambozzi L, Menzano A, Molinar Min AR, Rossi L. Immunoblot analysis of IgG antibody response to Sarcoptes scabiei in swine. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2007;115:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walton SF, Beroukas D, Roberts-Thomson P, Currie BJ. New insights into disease pathogenesis in crusted (Norwegian) scabies: the skin immune response in crusted scabies. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1247–1255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elder BL, Arlian LG, Morgan MS. Modulation of human dermal microvascular endothelial cells by Sarcoptes scabiei in combination with proinflammatory cytokines, histamine, and lipid-derived biologic mediators. Cytokine. 2009;47:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoefling KK, Schroeter AL. Dermatoimmunopathology of scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:237–240. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(80)80184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]