Abstract

Aims:

The effects of oral administration of nutmeg commonly used as spice in various dishes, as components of teas and soft drinks or mixed in milk and alcohol on the kidneys of adult Wistar rats were carefully studied.

Material and Methods:

Rats of both sexes (n = 24), with average weight of 220g were randomly assigned into two treatments (A & B) of (n=16) and Control (c) (n=8) groups. The rats in the treatment groups (A & B) received 0.1g (500mg/kg body weight) and 0.2g (1000mg/kg body weight) of nutmeg thoroughly mixed with the feeds respectively on a daily basis for forty-two days. The control group (c) received equal amount of feeds daily without nutmeg added for forty-two days. The growers’ mash feeds was obtained from Edo Feeds and Flour Mill Limited, Ewu, Edo state, Nigeria and the rats were given water liberally. The rats were sacrificed by cervical dislocation on the forty-third day of the experiment. The kidneys were carefully dissected out and quickly fixed in 10% buffered formaldehyde for routine histological study after hematoxylin and eosin method.

Result:

The histological findings in the treated sections of the kidneys showed distortion of the renal cortical structures, vacuolations appearing in the stroma and some degree of cellular necrosis, with degenerative and atrophic changes when compared to the control group.

Conclusion:

These findings indicate that oral administration of nutmeg may have some deleterious effects on the kidneys of adult Wistar rats at higher doses and by extension may affect its excretory and other metabolic functions. It is recommended that caution should therefore be advocated in the intake of this product and further studies be carried out to examine these findings.

Keywords: Nutmeg, histological effect, kidneys, degenerative changes, vacuolations and Wistar rats

Introduction

The Nutmeg plant, Myristica fragrans Houtt, is a member of the small primitive family called Myristicaceae, taxonomically placed between the Annonaceae and Lauraceae[1]. At Present, Myristicaceae is considered as a member of Magnotiales or its taxonomical equivalents[2,3]. Nutmeg has long been known for its psychoactive properties (producing anxiety/fear, Hallucination), from as early as 16th century writings to current internet based site[4,5,6].

Nutmeg is widely accepted as a flavouring agent, and was used in higher doses (500mg/kg) as aphrodisiac and psychoactive agent in male rat[7,8]. Nutmeg and its Oleoresin are used in the preparation of meat products, soaps, sauces, baked foods, confectioneries, puddings, seasoning of meat and vegetables, to flavor milk dishes and punches. Powdered nutmeg is rarely administered alone, but enters into the composition of numerous medicines such as aromatic adjuncts. Medicinally, nutmeg is known to be a stimulant and has carminative properties[9,10]. In pregnancy and lactation, traditionally Nutmeg has been used as an abortificient; though this has largely been discounted, but it remains a persistent cause of nutmeg intoxication in women[11]. The active ingredient in nutmeg is called Myristicine and is a naturally occurring insecticide and acaricide with possible neurotoxic effects on dopaminergic neurons and a monoamine oxide[12,13]. Cytotoxic and apotoxic effects of Myristicine have been reported such that cell viability was reduced by exposure to Myristicine in a dose dependent manner[13].

Olaleye et al. reported that the phytochemical constituent of nutmeg includes alkaloids, saponins, anthraquinones, cardiac glycosides, flavonoids and phlobatanins, while tannins were absent in the aqueous extract. The phytate content was reported to be 564.11 mg/100 g while the antioxidant indices of 100 mg/100 g, 44% and 0.6 were obtained for the ascorbic acid value, free radical scavenging activity and reducing power, respectively[14].

The Kidney is a paired organ located in the posterior abdominal wall, whose functions include removal of waste products from the blood and regulation of the amount of fluid and electrolytes balance in the body. As in humans, the majority of drugs administered are eliminated by a combination of hepatic metabolism and renal excretion[15]. The kidney also plays a major role in drug metabolism, but its major importance to drugs is still its excretory functions. It would therefore be worthwhile to examine the effects of Nutmeg on the kidneys of adult Wistar rat thereby either corroborating previous work done by other researchers[14], or disproving the toxic effects of nutmeg in this organ, with a view to advising the consumers on the inherent dangers of excessive consumption of the spice/aphrodisiac.

Materials and Methods

This study was given approval for the methodology and other ethical issues concerning the work by the University of Benin Research Ethics Committee.

Animals

Twenty-four adult Wistar rats of both sexes with average weight of 220g were randomly assigned into three groups: A, B and C of (n=8) in each group. Group A and B served as treatment groups (n=16) while group C (n=8) served as the control. The rats were obtained and maintained in the Animal Holding of the Department of Anatomy, School of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Benin, Edo State, Nigeria. The animals were fed with growers’ mash obtained from Edo Feeds and Flour Mill Limited, Ewu, Edo State, Nigeria and given water liberally. The Nutmeg seeds were obtained from New Benin Market, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria. They were dried and graded into powder at the Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Benin, Benin City, Nigeria.

Nutmeg Administration

The rats in the treatment groups (A & B) were given 0.1g (500mg/kg body weight) and 0.2g (1000mg/kg body weight) of nutmeg thoroughly mixed with the feeds respectively on a daily basis for forty-two days (6 weeks). The control group (c) received equal amount of feeds without Nutmeg added for the same period.

Histological Study

Blood samples were collected and analyzed for blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine (Scr) by using the commercial kits[16] on the forty- third day of the experiment. After bleeding, the rats were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and the abdominal cavity was opened up using a pair of forceps to expose the kidneys which were quickly dissected out and fixed in 10% formal saline for routine histological techniques. The tissues were dehydrated in an ascending grade of alcohol (ethanol), cleared in xylene and embedded in paraffin wax. Serial sections of 7 microns thick were obtained using a rotatory microtome. The deparaffinized sections were stained routinely with hematoxylin and eosin[17]. Photomicrographs of the desired sections were made for further observations.

Statistical Analysis

The results are expressed as mean±SD. Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance. Sequential differences among means were calculated at the level of P< 0.05, using Turkey contrast analysis as needed.

Result

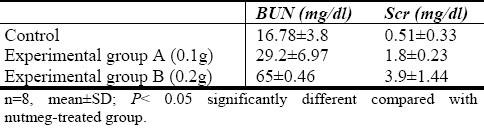

The result of this experiment revealed that nutmeg consumption caused significant (P<0.05) increase in functional nephrotoxicity indicators such as BUN and Scr in nutmeg-treated rats compared with control (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of long time consumption of nutmeg (0.1g and 0.2g) on BUN and Scr concentration

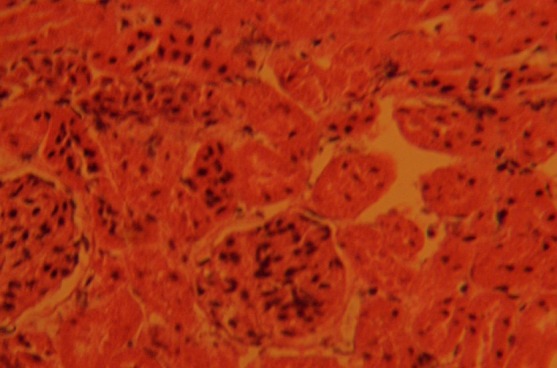

The control sections of the kidneys showed normal histological features. The section indicated a detailed cortical parenchyma and the renal corpuscles appeared as dense rounded structures with the glomerulus surrounded by a narrow Bowman's spaces (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Control section of kidney; this shows cortical parenchyma to consist of dense rounded structures, the glomeruli (G), surrounded by narrow Bowman's capsular spaces (BCS). H&E (Mag. ×400).

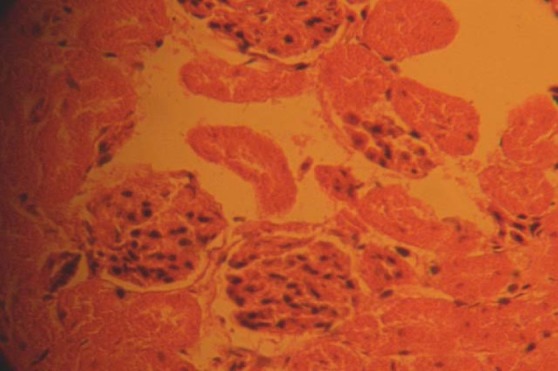

The kidneys of the animals in group A treated with 0.1g/day of nutmeg revealed some level of cyto-architectural distortion of the cortical structures as compared to the control (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

Photomicrograph of treatment section of the kidney of rats that received 0.1g of nutmeg revealing some level of cyto-architectural distortion (CAD). H&E (Mag. ×400).

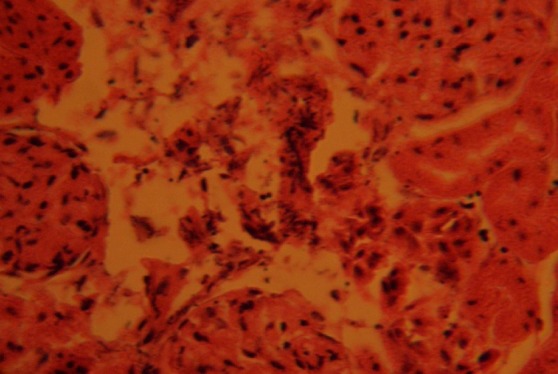

The kidney sections of animals in group B treated with 0.2g/day of nutmeg revealed marked distortion of cyto-architecture of the renal cortical structures, and degenerative and atrophic changes. There were vacuolations appearing in the stroma. The renal corpuscles were less identified and the Bowman's spaces were sparsely distributed as compared to the control group (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Treatment section of the kidney of rats that received 0.2g of nutmeg, revealing some level of cyto-architectural distortion (CAD), degenerative and atrophic changes (ADC), and vacuolations (V) appearing in the stroma. H&E (Mag. ×400).

Discussion

The results (H & E) reactions revealed that chronic consumption of nutmeg caused varying degree of cyto-architectural distortion and reduction in the number of renal corpuscle in the treated groups compared to the control group. There were several diffuse degeneration and necrosis of the tubular epithelial cells in the kidneys of the treated animals. The degenerative and atrophic changes where observed more in the kidneys of rats that received the higher dose (0.2g) of nutmeg.

It may be inferred from the present results that higher doses of nutmeg consumption may have resulted in degenerative and atrophic changes observed in the renal corpuscle. The possible deduction from these results is that secondary metabolites, which are largely responsible for therapeutic or pharmacological activities of medicinal plants[18], may also account for their toxicity when the dosage is abused.

The actual mechanism by which nutmeg induced cellular degeneration observed in this experiment needs further investigation. The necrosis observed is probably due to the high concentration of nutmeg on the kidney. Pathological or accidental cell death is regarded as necrotic and could result from extrinsic insults to the cell as osmotic thermal, toxic and traumatic effect[19]. Physiological cell death is regarded as apoptotic and organized programmed cell death (PCD) that is mediated by active and intrinsic mechanisms. The process of cellular necrosis involves disruption of membranes, as well as structural and functional integrity. Cellular necrosis is not induced by stimuli intrinsic to the cells as in programmed cell death (PCD), but by an abrupt environmental perturbation and departure from the normal physiological conditions[19].

In cellular necrosis, the rate of progression depends on the severity of the environmental insults: the greater the severity of the insult, the more rapid the progression of cellular injury. The principle holds true for toxicological insult to the brain and other organs[20]. It may be inferred from the present study that prolonged administration and higher doses of nutmeg resulted in increased toxic effect on the kidney. Our results are in agreement with previous studies[14] that indicated nutmeg to be toxic to the kidneys when abused.

Conclusion

The results obtained in this study revealed that Nutmeg consumption could affect the histology of the kidney of adult Wistar rat; causing disruptions and distortions of the cyto-architecture of the kidneys. This resulted in the cellular necrosis, and sparsely distribution of the Bowman's spaces. These results suggest that the functions of the kidney may have been adversely affected. It is recommended that caution should therefore be advocated in the intake of this product and further studies be carried out to examine these findings.

References

- 1.Joseph J. The Nutmeg, its Botany, Agronomy, Production, Composition and Uses. 1980;2:61–67. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cronquist A. New York: A textbook: Columbia University press; 1983. An integrated system of classification of flowering plants. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahlgren R. General aspect of angiosperm evolution and macrosystematics. Nordic J Bot. 1983;3:119–149. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner N, Frank OS, Knight E. Chronic Nutmeg Pschosis. 1993;86:179–180. doi: 10.1177/014107689308600326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly BD, Gavin BE, Clarke M, Lane A, Larkin C. Nutmeg and Psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2003;60:85–96. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forrester MB. Nutmeg Intoxication in Texas, 1998 - 2004. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2005;24:563–566. doi: 10.1191/0960327105ht567oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tajuddin S, Ahmad S, Latif A, Qasmi IA. Aphodisiac Activity of 50% Ethanol extract of myristica fragrans Houtt (Nutmeg) and Syzygium aromaticum (L) Merr and Perry (Clove) in male mice: A Comparative study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2003;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tajuddin S, Ahmad S, Latif A, Qasmi IA, Amin KM. An Experimental Study of Sexual Function Improving Effect of Myristica fragrans Houtt. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2005;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lagouri V, Boskou D. Screening for Antioxidant Activity of Essential Oils obtained from spices. In: Charalambous G, editor. food flavors: Generation, analysis and process influence. Amsterdam, Elsevier: 1995. pp. 869–79. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madsen HL, Bertelsen G. Spices as antioxidants. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1996;6:271–277. [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Milto L, Frey RJ. Nutmeg. In: Longe J.L, editor. Gale Encyclopedia of Alternative Medicine. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Detroit, ML: Thomson Gale; 2005. pp. 1461–1463. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Truitt EB, Duritz G, Ebersberger EM. Evidence of Mondamine Oxidase Inhibition by Myristicin and Nutmeg. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1963;112:647–650. doi: 10.3181/00379727-112-28128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee BK, Kim JH, Jung JW. Myristicin-induced Neurotoxicity in Human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH Cells. Toxicol Lett. 2005;157:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olaleye MT, Akinmoladun AC, Akindahunsi AA. Antioxidant properties of Myristica fragrans (Houtt) and its effect on selected organs of albino rats. AJB. 2006;5(13):1274–1278. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katzung BG. Appleton and Lange. 7th ed. Stamford CT: 1998. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology; pp. 372–375. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McClatchey KD. London: Williams & Wilkins; 1994. Clinical Laboratory Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drury RAB, Wallington EA, Cameron R. 4th ed. U.S.A: Oxford University Press NY; 1967. Carleton's Histological Techniques; pp. 279–280. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perry LM. Oxford University Press NY; 1980. Medicinal plants of East and South East Asia, MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farber JL, Chein KR, Mittnacht S. The pathogenesis of irreversible cell injury in ischemia. Am J Pathol. 1981;102:271–281. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martins LJ, Al-Abdulla NA, Kirsh JR, Sieber FE, Portera-Cailliau C. Neurodegeneration in excitotoxicity, global cerebral ischaemia and target.Deprivation: A perspective on the contributions of apoptosis and necrosis. Brain Res Bull. 1998;46(4):281–309. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]