Abstract

Background:

The effect of monosodium glutamate used as food additive on the fallopian tubes of adult Wistar rat was investigated.

Material and Methods:

Adult female Wistar rats (n=24) of average weight of 230g were randomly assigned into three groups A, B and C in each group (n=8). The treatment groups (A & B) were given 0.04mg/kg and 0.08mg/kg of monosodium glutamate thoroughly mixed with the growers’ mash, respectively on a daily basis. The control group (C) received equal amount of feeds (Growers’ mash) without monosodium glutamate added for fourteen days. The growers’ mash was obtained from Edo Feeds and Flour Mill Ltd, Ewu, Edo State and the rats were given water liberally. The rats were sacrificed on day fifteen of the experiment. The fallopian tubes were carefully dissected out and quickly fixed in 10% buffered formaldehyde for routine histological procedures.

Result:

The histological findings in the treated groups showed evidence of cellular hypertrophy, degenerative and atrophic changes, and lysed red blood cells in lumen with the group that received 0.08mg/kg of monosodium glutamate more severe.

Conclusion:

MSG may have some deleterious effects on the fallopian tubes of adult female Wistar rats at higher doses and by extension may contribute to the causes of female infertility. It is recommended that further studies aimed at corroborating these findings be carried out.

Keywords: Monosodium glutamate, Histological effect, fallopian tubes, Degenerative changes, vacuolations, Wistar rats

Introduction

Various environmental chemicals, industrial pollutants and food additives have been implicated as causing harmful effects[1]. Most food additives act either as preservatives, or enhancer of palatability. One such food additive is Monosodium glutamate (MSG) and it is sold in most open market stalls and stores in Nigeria as “Ajinomoto” marketed by West African Seasoning Company Limited.

The safety of MSG's usage has generated much controversy locally and globally[2]. In Nigeria, most communities and individuals often use MSG as a bleaching agent for the removal of stains from clothes. There is a growing apprehension that its bleaching properties could be harmful or injurious to the body, or worse still inducing terminal diseases in consumers when ingested as a flavour enhancer in food. Despite evidence of negative consumer response to MSG, reputable international organizations and nutritionist have continued to endorse MSG, reiterating that it has no adverse reactions in humans. Notably of such is the Directorate and Regulatory Affairs of Food and Drug Administration and Control (FDA&C) in Nigeria, now NAFDAC has also expressed the view that MSG is not injurious to health[3].

MSG improves the palatability of meals and thus influences the appetite centre positively with it resultant increase in body weight[4,5,6]. Though MSG improves taste stimulation and enhances appetite, reports indicate that it is toxic to human and experimental animals[7]. MSG has a toxic effect on the testis by causing a significant oligozoospermia and increase abnormal sperm morphology in a dose-dependent fashion in male Wistar rats[8]. It has been implicated in male infertility by causing testicular hemorrhage, degeneration and alteration of sperm cell population and morphology[9]. It has been reported that MSG has neurotoxic effects resulting in brain cell damage[10], retinal degeneration, endocrine disorder and some pathological conditions such as addiction, stroke, epilepsy, brain trauma, neuropathic pain, schizophrenia, anxiety, depression, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis[11]. It cannot be stated that MSG is the cause of such varied conditions as epilepsy and Alzheimer's disease, although there may be concerns of its involvement in its etiology.

The Fallopian tubes are paired, tubular, seromuscular organs whose course runs medially from the cornua of the uterus toward the ovary laterally at the upper margins of the broad ligaments between the round and utero ovarian ligaments[12]. Millions of tiny hair-like cilia which beats in waves hundreds of times a second catching the egg at ovulation and moving it through the tube to the uterine cavity, line the fimbria and interior of the fallopian tubes. Other cells in the tube's inner lining or endothelium nourish the egg and lubricate its path during its stay inside the fallopian tube.[13].

The tubal wall consists of three layers: the internal mucosa (endosalpinx), the intermediate muscular layer (myosalpinx), and the outer serosa, which is continuous with the peritoneum of the broad ligament and uterus, the upper margin of which is the mesosalpinx. The endosalpinx is thrown into longitudinal folds, called primary folds, increasing in number toward the fimbria and lined by columnar epithelium of three types: ciliated, secretory, and peg cells. In the ampullary and infundibular sections, secondary folds of the tubal mucosa also exist, markedly increasing the surface areas of these segments of the tube. The myosalpinx actually consists of an inner circular and an outer longitudinal layer to which a third layer is added in the interstitial portion of the tube. The serosa of the tube is composed of an epithelial layer histologically indistinguishable from peritoneum elsewhere in the abdominal cavity[13].

This work was carried out to investigate some probable histological effects of MSG on the fallopian tubes and its likely involvement in female infertility in Nigeria.

About 15% cases of female infertility, investigation will show no abnormality. In these cases abnormalities are likely to be present but not detected by current methods[14].

Materials and Methods

This study was given approval for the methodology and other ethical issues concerning the work by the University of Benin Research ethics committee.

Twenty four, (24) adult female Wistar rats with average weight of 230g were randomly assigned into three groups A, B and C of (n=8) in each group. Groups A and B (n=16) serves as treatment groups while Group C (n=8) was the control. The rats were obtained and maintained in the Animal Holdings of the Department of Anatomy, School of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Benin, Benin city, Nigeria. They were fed with growers’ mash obtained from Edo feed and flour mill limited, Ewu, Edo state, and were given water liberally.

The rats gained maximum acclimatization before actual commencement of the experiment. The monosodium glutamate (3g/sachet containing 99+% of MSG) was obtained from Kersmond grocery stores, Uselu, Benin City.

Monosodium Glutamate Administration: The rats in the treatment groups (A and B) were given 0.04mg/kg and 0.08mg/kg of MSG thoroughly mixed with the growers’ mash, respectively on a daily basis. The control group (C) received equal amount of feeds (growers’ mash) without MSG added for fourteen days.

The rats were sacrificed on the fifteenth day of the experiment. The fallopian tubes were quickly dissected and fixed in 10% buffered formaldehyde for 24 hours and embedded in paraffin wax for routine histological techniques.

The 0.04mg/kg and 0.08mg/kg MSG doses were chosen and extrapolated in this experiment based on the indiscriminate use here in Nigeria due to its palatability, and previous work done with this additive[15,16]. The two doses were thoroughly mixed with fixed amount of feeds (550g) in each group, daily.

Histological Study: The fallopian tube tissues were dehydrated in an ascending grade of alcohol (ethanol), cleared in xylene and embedded in paraffin wax. Serial sections of 7 microns thick were obtained using a rotatory microtome. The deparaffinised sections were stained routinely with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) method[17]. Ph otomicrographs of the desired results were obtained using digital research photographic microscope in the University of Benin research laboratory.

Results

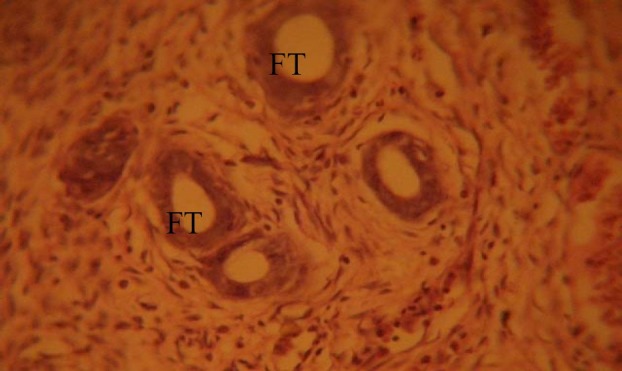

The fallopian tubes (FT) of the control group showed normal histological features, illustrating a well defined tubal wall which consists of three layers: the internal mucosa (endosalpinx), the intermediate muscular layer (myosalpinx), and the outer serosa (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Control section of the fallopian tubes (FT), H&E. (Mag. ×400). FT: fallopian tube.

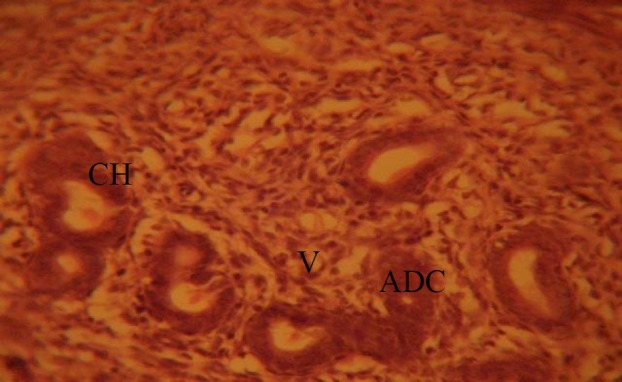

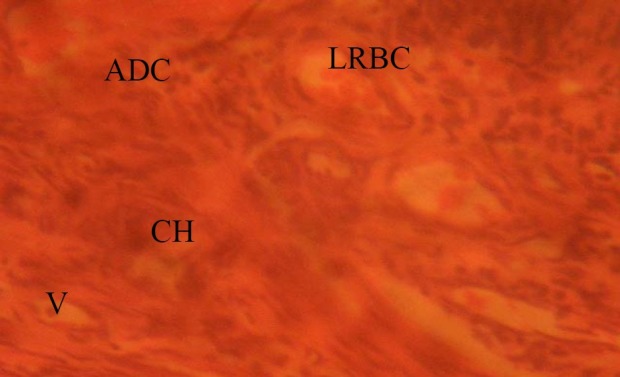

The fallopian tubes of the treated groups showed some cellular hypertrophy (CH) of the columnar epithelium, distortion of the basement membrane separating the endosalpinx from the myosalpinx. There were degenerative and atrophic changes (ADC) observed in some parts; these were more pronounced in those that received 0.08mg/kg of MSG. There were marked vacuolations (V) and lysed red blood cells (LRBC), (0.08mg/kg treated rats) appearing in the stroma cells (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2.

Treatment section of the fallopian tubes that received 0.04mg/kg MSG. H&E (Mag. ×400). ADC: atrophic and degenerative changes; CH: cellular hypertrophy; V: vacuolation.

Fig. 3.

Treatment section of fallopian tubes (0.08mg/kg MSG); H&E (Mag. ×400). ADC: atrophic and degenerative changes; V: vacuolation; CH: cellular hypertrophy; LRBC: lysed red blood cells.

Discussion

The results of the hematoxylin and eosin staining (H & E) reactions showed some cellular hypertrophy of the columnar epithelium, distortion of the basement membrane separating the endosalpinx from the myosalpinx. Degenerative and atrophic changes were observed in some parts; these were more pronounced in those that received 0.08mg/kg of MSG. There were marked vacuolations and lysed red blood cells (0.08mg/kg treated rats) appearing in the stroma cells.

The increase in cellular hypertrophy of the columnar epithelium in the treatment groups as reported in this study may have been as a result of cellular proliferation caused by the improved intake of food which MSG influences[4,5,6]. The vacuolations observed in the stroma of the fallopian tubes in this experiment may be due to MSG interference. Degenerative and atrophic changes and lysed red blood cell which were observed were more pronounced in the groups treated with higher dose (0.08mg/kg) of MSG.

As a result of the distortion and disruption in the lumen of the fallopian tubes, the ciliary action and other functions of the fallopian tubes may have been highly affected as a result of probable toxic effect of MSG. It may be inferred from the present results that higher dose and prolonged administration of MSG resulted in degenerative and atrophic changes observed in the fallopian tubes. The actual mechanism by which MSG induced cellular degeneration observed in this experiment needs further investigation.

Degenerative changes have been reported to result in cell death, which is of two types, namely apoptotic and necrotic cell death. These two types differ morphologically and biochemically[18]. Pathological or accidental cell death is regarded as necrotic and could result from extrinsic insults to the cell such as osmotic, thermal, toxic and traumatic effects[19]. In this experiment MSG could have acted as toxins to the epithelial cells of the fallopian tubes. The process of cellular necrosis involves disruption of membrane's structural and functional integrity which was also a landmark of this experiment.

Cell death in response to toxins occurs as a controlled event involving a genetic programme in which caspase enzymes are activated[20].

Conclusion

The results obtained in this study following the administration of 0.04mg/kg and 0.08mg/kg per day of MSG to adult Wistar rats caused some cellular hypertrophy of the columnar epithelium, distortion of the basement membrane separating the endosalpinx from the myosalpinx. Degenerative and atrophic changes, which were more pronounced in those that received 0.08mg/kg of MSG. There were marked vacuolations and lysed red blood cell appearing in the stroma cell.

It is recommended that further studies be carried out to corroborate these findings.

References

- 1.Moore KL. Chap 8. 2nd Ed. Philadelphia: Developing Humans W.B. Saunders Co. Ltd; 2003. Congenital malformations due to environmental factors; pp. 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biodun D, Biodun A. A spice or poison? Is monosodium glutamate safe for human consumption? National Concord Newspaper. 1993;4:5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okwuraiwe PE. The role of food and Drug Administration and control (FDA&C) in ensuring the safety of food and food ingredients: A symposium held at Sheraton Hotel, Lagos. 1992 Sep 1st;:6–15. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogers PP, Blundell JE. Umani and appetite: Effects of monosodium glutamate on hunger and food intake in human subjects. Physiol Behav. 1990;48(6):801–804. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwase M, Yamamoto M, Iino K, Ichikawa K, Shinohara N, Yoshinari F. Obesity induced by neonatal monosodium glutamate treatment in spontaneously hypertensive rats: an animal model of multiple risk factors’. Hypertens Res. 1998;43:62–28. doi: 10.1291/hypres.21.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gobatto CA, Mello MA, Souza CT, Ribeiro IA. The monosodium glutamate (MSG) obese rat as a model for the study of exercise in obesity. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol. 2002;(2):116–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belluardo M, Mudo G, Bindoni M. Effect of early destruction of the mouse arcuate nucleus by MSG on age dependent natural killer activity: Brain Res. 1990;534:225–333. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90132-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Onakewhor JUE, Oforofuo IAO, Singh SP. Chronic administration of Monosodium glutamate Induces Oligozoospermia and glycogen accumulation in Wister rat testes. Africa J Reprod Health. 1998;2(2):190–197. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oforofuo IAO, Onakewhor JUE, Idaewor PE. The effect of chronic admin of MSG on the histology of the Adult Wister rat testes. Biosc Resch Comms. 1997;9(2):6–15. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eweka AO, Adjene JO. Histological studies of the effects of monosodium Glutamate on the medial geniculate body of adult Wister rat. Electron J Biomed. 2007;22:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samuels A. The Toxicity/Safety of MSG: A study in suppression of information. Acctabil Resch. 1999;6(4):259–310. doi: 10.1080/08989629908573933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hershlag A, Diamond MP, DeCherney AH. Tubal physiology: An appraisal. J Gynecol Surg. 1989;(5):2–25. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berger G. Tubal reversal ligation: Chapel Hill Tubal reversal center. (Accessed December 6, 2009, at http://www.tubal-reversal.net/fallopian-tubes. ) [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Society for Reproductive Medicine; (FAQ) 2006. (Accessed December 6, 2009, at http://www.asrm.org/Patients/faqs.html. )

- 15.Eweka AO, Om’Iniabohs FAE. Histological studies of the effects of monosodium glutamate on the small intestine of adult Wistar rat. Electron J Biomed. 2007;2:14–18. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eweka AO, Om’Iniabohs F.A.E, Adjene J.O. Histological studies of the effects of monosodium glutamate on the stomach of adult Wistar rats. Ann Biomed Sci. 2007;6:45–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drury RAB, Wallington EA, Cameron R. Carleton's Histological Techniques. 4th ed. NY. USA: Oxford University Press; 1967. pp. 279–280. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wyllie AH. Nature. Vol. 284. London: 1980. Glucocorticoid-induced thymocyte apoptosis is associated with endogenous endonuclease activation; pp. 555–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farber JL, Chein KR, Mittnacht S. The pathogenesis of irreversible cell injury in ischemia. Am J Pathol. 1981;102:271–281. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waters CM, Walkinshaw G, Moser B, Mitchell IJ. Death of neurons in the neonatal rodent globus pallidus occurs as a mechanism of apoptosis. Neuroscience. 1994;63:881–894. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]