Abstract

Background:

Wall shear stress is thought to play a critical role in the local development of atherosclerotic plaque and to affect plaque vulnerability. However, current models and hypotheses do not fully explain the link between wall shear stress and local plaque development. We aimed to investigate the relation between wall shear stress and local plaque development in surgically induced common carotid artery stenoses of hypercholesterolemic minipigs.

Materials, Methods and Results:

We created a surgically induced stenosis of the common carotid artery in 10 minipigs using a perivascular collar. We documented the flow and shear stress changes by ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, and computational fluid dynamics. Carotid plaques were documented by microscopy. Atherosclerotic lesions, in both pre-stenotic and post-stenotic segments, were associated with thrombus in the stenosed segment. In patent carotid arteries, atherosclerotic lesions were found in the post-stenotic segments only. Atherosclerotic lesions developed where low and oscillatory shear stress were present simultaneously, whereas low or oscillatory shear stress alone did not lead to lesion formation.

Conclusions:

Low and oscillatory shear stress in combination promoted plaque development, including plaques with necrotic cores that are the key and dangerous characteristic of vulnerable plaques.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, carotid artery, magnetic resonance imaging, vulnerable plaque, wall shear stress

INTRODUCTION

Vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques with a necrotic core may rupture and cause thrombosis.[1] This is the main mechanism underlying coronary and carotid thrombosis.[2–4] Low or oscillatory wall shear stress is thought to play a critical role in the development of atherosclerosis and may also affect plaque vulnerability.[5,6] In experimental models, surgically induced stenosis of the common carotid artery is used to disturb common carotid blood flow thereby changing wall shear stress. In hypercholesterolemic mice and pigs, this can induce atherosclerotic plaques with morphology similar to human vulnerable plaques in the common carotid artery that is otherwise spared for atherosclerosis, even in hypercholesterolemic animals.[6–13]

Previously, conclusions on the effects of low and oscillatory shear stress have been made in the murine carotid stenosis model.[6] Wall shear stress was estimated based on Doppler ultrasound blood flow measurement and a theoretical model of the anatomy. It was concluded that low-shear stress proximal to the stenosis led to formation of lesions with a vulnerable phenotype and that oscillatory shear stress distal to the stenosis led to formation of lesions with a stable phenotype. This does not explain why plaque usually develops immediately proximal to the stenosis and not in the entire pre-stenotic segment, although this has the same low flow and shear stress, or why the left anterior descending artery and the carotid artery are more prone to atherosclerosis than the femoral artery,[14,15] although wall shear stress is lower in the femoral artery than in the left anterior descending artery and the carotid artery.[16] Also, severe stenosis is associated with post-stenotic dilatation. With the same volumetric flow proximal and distal to the stenosis, post-stenotic dilatation should be associated with lower linear flow velocity and hence wall shear stress distal to the stenosis compared to proximal to the stenosis.

To address some of these unresolved questions, we aimed to investigate the relation between wall shear stress and local plaque development in surgically induced common carotid artery stenoses of hypercholesterolemic minipigs. Minipigs are closer to human size and thereby a more detailed assessment of carotid flow and anatomy is possible. We assessed carotid artery blood flow and anatomy with magnetic resonance imaging and performed a detailed description of local wall shear stress with computational fluid dynamics. Local development of atherosclerotic lesions was assessed by microscopic examination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Danish Animal Experiments Inspectorate.

Minipigs and protocol

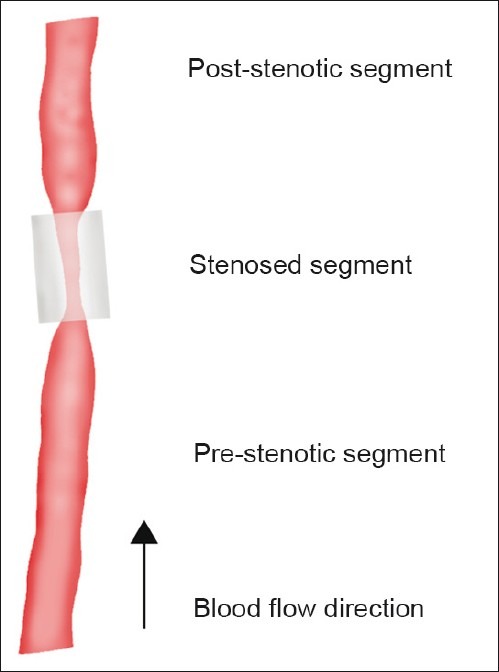

Ten male castrated minipigs, with familial hypercholesterolemia due to a low-density lipoprotein receptor mutation,[17–19] were fed an atherogenic diet for 18 weeks. After 4 weeks on the atherogenic diet, surgical stenosis of one carotid artery was induced by placement of a silicone collar, with an inner diameter of 2 mm, around the carotid artery. The intention was to create common carotid artery stenoses that reduced the common carotid artery blood flow by approximately 75%. The collar was made from a silicone tube slit open longitudinally. This allowed its placement around the artery. In place, the tube was closed with two ligatures to form the stenosing collar. The collar then divided the common carotid artery into three segments: A pre-stenotic segment, a stenosed segment, and a post-stenotic segment [Figure 1]. Carotid blood flow was measured perioperatively in the proximal segment before and after the placement of the collar with a transit time flow probe.[20] To reduce the risk of clotting and thrombosis, the minipigs received unfractioned heparin in relation to the procedures and aspirin (150 mg daily) after the procedures.

Figure 1.

Common carotid artery collar model. Surgical stenosis was induced by placement of a silicone collar (inner diameter 2 mm, length 1 cm) around the carotid artery. The collar divided the common carotid artery into three segments: A pre-stenotic segment, a stenosed segment, and post-stenotic segment

During the study, the minipigs were weighed and blood samples were drawn after 2 weeks, 4 weeks, 14 weeks and 18 weeks on the atherogenic diet and analyzed for plasma cholesterol.

Carotid ultrasound

Carotid ultrasound was performed on sedated minipigs (azaperone and midazolam) 12 weeks after the surgery. Color Doppler and spectral Doppler investigation was performed (GE LOGIQ 9, GE Healthcare, Brøndby, Denmark) with a 4 MHz multi frequency curved array or a 10 MHz multifrequency linear transducer depending on the depth. Spectral Doppler data were collected twice in the proximal and stenosed segments. Flow volume was determined by software in the ultrasound device using mean flow velocity and artery diameter. Mean value of two measurements was used. The stenosis degree was determined by the peak flow velocity ratio between the stenosed segment and the proximal segment.[21] The highest peak flow value of the two measurements was used.

MRI and wall shear stress assessment

MRI was performed on seven of the minipigs immediately before termination of the study. During the scan, the minipigs were sedated with a continuous propofol infusion. From stacks of 45 MR images of each carotid artery, manual segmentations were performed using ScanIP (Simpleware Ltd., Exeter, UK) generating three-dimensional models of the carotid arteries. The models were further processed using ScanFE (Simpleware) in order to create a mesh for use with computational fluid dynamics. The mesh was imported into the Finite Element software Comsol Multiphysics 3.4 (COMSOL inc., Stockholm, Sweden). In Comsol Multiphysics, the inlet boundary conditions were applied to the models as time-dependent velocities. Velocity data were obtained from the MRI phase contrast flow measurement generating 20 measure points (time steps) during a heart phase of the average cross-sectional velocity of the carotid artery. The outlet boundary condition was a pressure condition with a value of 0.

Blood was simulated as being a homogenous Newtonian fluid with a density of 1030 kg/m and a viscosity of 3.6·10-3Pa·s. In all simulations, velocities at the wall boundaries were set to zero, the so-called “no slip” condition. Arterial compliance was considered negligible and was not included. Numerical time dependent simulations of blood flow within the carotid arteries were performed employing the generalized isothermal Navier-Stokes equation formulated as conservation of mass and momentum in Comsol Multiphysics. Wall shear stress data were derived from time-dependent simulations by calculating the viscous stress tensor τ and visualized using the postprocessing tools in Comsol. In addition, visualization of the blood flow streamlines were also performed using the Comsol Interface. From the time-dependent simulations, wall shear stress data were derived for each time step in the simulation. These data were further processed using Matlab R2007b (MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts, U.S.) to visualize the location and magnitude of oscillatory wall shear stress.

Angiography

Conventional angiography was performed immediately before termination. Stenosis length and luminal diameters in the proximal, stenosed and distal segments, and angiographic stenosis degree ([1-stenosis diameter/proximal diameter]·100) and distal dilatation (distal diameter/proximal diameter-1) was calculated.

Microscopic examination

The carotid arteries were excised and pressure fixed with 4% formaldehyde at 100 mmHg for 1 h and subsequently immersion fixed for 6–12 h. The arteries were sectioned at 4-mm intervals, paraffin embedded, and sectioned for microscopic examination. Hematoxylin and eosin and trichrome-elastin stains were produced on all sections. To support interpretations based on these staining methods, picrosirius red (collagen) and von Kossa staining in addition to immunohistochemistry for smooth muscle cells (Anti-Smooth Muscle Actin, DAKO M0851), macrophages (Anti-Lysozyme 12, DAKO A0099[22]), and endothelium (Biotinylated Griffonia Simplicifolia Lectin I, Vector Laboratories B-1105, Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) were performed on selected sections.

Digital photomicrographs were obtained and measurements on areas and thicknesses were performed in Image J. Intimal areas were measured on digital images of all sections outside the stenosed segments. In the section with the largest intimal area, the intimal lesion was graded. In the stenosis, the most advanced intimal lesion was also graded.

Statistical analysis

Categorical values are presented as counts (frequencies) and numerical values as means (standard deviations). Comparisons of numerical values were performed with the Kruskal-Wallis test (Stata/IC 10.1 for Windows, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

One minipig died during follow-up in relation to blood sampling.

Feeding, body weights, and plasma analyses

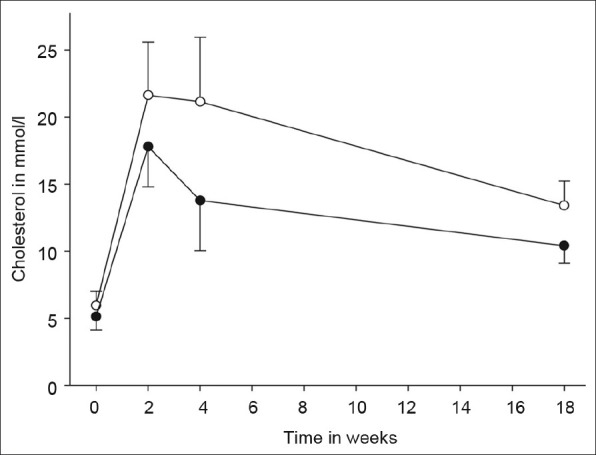

All but one minipig (84 kg) weighed between 30 kg and 50 kg at the end of the study. Mean plasma total cholesterol was 6.0 mmol/L (0.3 mmol/L) on standard diet at baseline and peaked at 21.6 mmol/L (1.3 mmol/L) on the atherogenic diet, and the rise in total cholesterol was mainly caused by a rise in the low-density lipoprotein fraction [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Time course of cholesterol levels. Total (open circles) and low-density lipoprotein (filled circles) cholesterol levels over the course of the study. Error bars represent standard deviations

Carotid flow and angiography

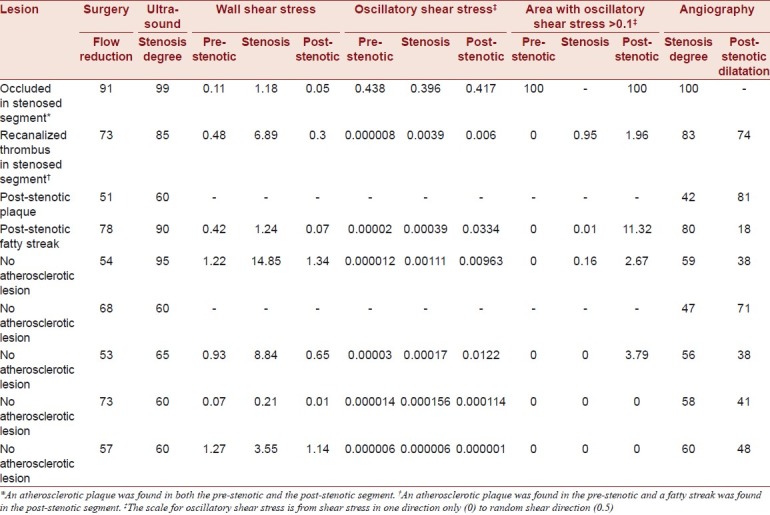

The data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Individual flow and shear stress in nine hypercholesterolemic minipigs with surgically induced carotid stenosis

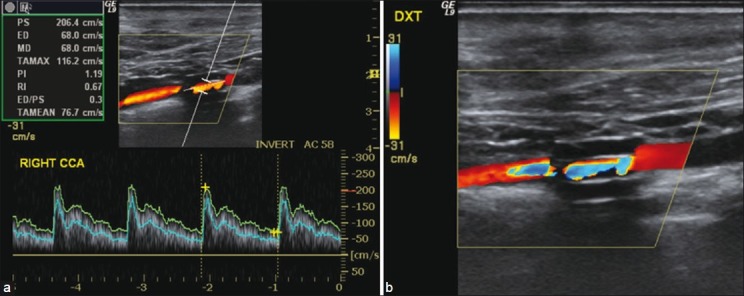

One carotid artery was occluded and not included in the calculated means. Collar placement reduced perioperative transit time carotid blood flow by 66% (15%). By ultrasound [Figure 3], the stenoses degree was 75% (17%) and the peak systolic flow velocity in the stenoses was 222 cm/s (91 cm/s). Evaluated with MRI, the stenoses reduced flow by 70% (29%).

Figure 3.

Ultrasound stenosis evaluation in a surgically stenosed carotid artery of a hypercholesterolemic minipig. (a) Peak systolic velocity (PS) 206 cm/s in the stenosed segment. (b) Color Doppler showing the proximal segment (right), the stenosed segment, and the distal segment with turbulence (left). The collar material has low echogenicity and the collar is clearly visible around the stenosed segment

One stenosed segment was occluded and not included in the calculated means. On MRI, the cross-sectional areas were reduced by 61% (13%) in the stenosed segment compared to the proximal segment. On conventional angiography, the stenosis length was 11 mm (1 mm), the diameter stenosis degree was 61% (14%), and the distal dilatation degree was 51% (22%).

Wall shear stress

The data are presented in Table 1 and summarized in Table 2. An example is shown in Figure 4.

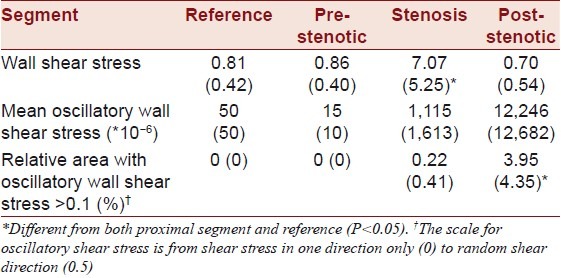

Table 2.

Summarized wall shear stress and oscillatory wall shear stress in patent carotid arteries

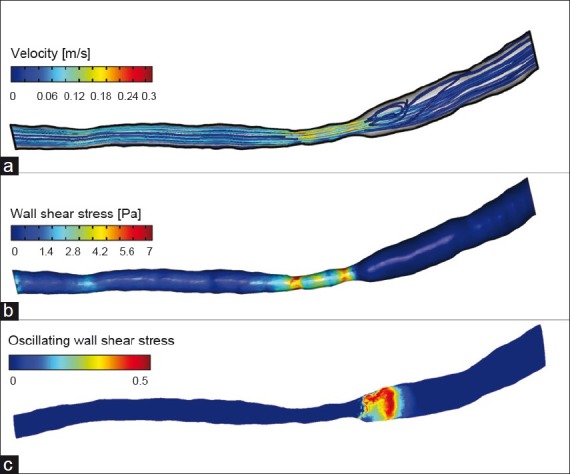

Figure 4.

Magnetic resonance imaging stenosis evaluation in a surgically stenosed carotid artery of a hypercholesterolemic minipig. (a) Flow velocity (b) Wall shear stress. (c) Oscillatory wall shear stress; the scale for oscillatory shear stress is from shear stress in one direction only (0) to random shear direction (0.5). This minipig had distal segment oscillatory wall shear stress with corresponding lesion development

Wall shear stress in the three carotid segments was compared to a control segment in the contralateral carotid artery. Among the three carotid segments, wall shear stress was highest in the stenosed segment and it tended to be higher in the pre-stenotic segment than in the post-stenotic segment. Oscillatory shear stress was found mainly in the stenotic and post-stenotic segments and was more pronounced in the post-stenotic segments.

Microscopic examination

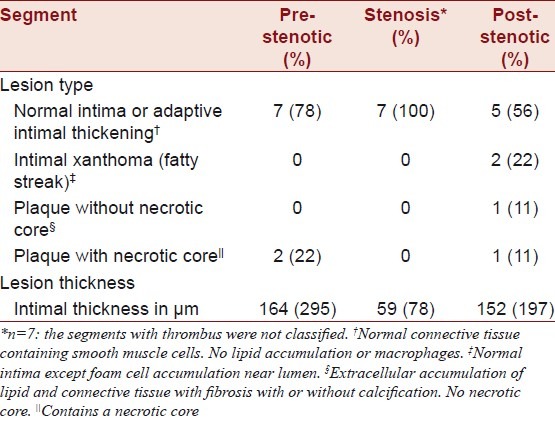

The data are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Lesion type and thickness in carotid artery segments

Microscopic examination revealed that the cause of the occlusion seen in one pig was thrombosis. The thrombus was organized, indicating that it had occurred at the time of collar placement. In another of the stenosed segments, microscopic examination revealed a recanalized thrombus. This thrombus had probably also formed immediately after the surgical procedure and subsequently recanalized [Figure 5]. In both these minipigs, the lumen was patent in the pre-stenotic and post-stenotic segments. In the carotid with the occluded stenotic segment, a plaque with a necrotic core was found both in the pre-stenotic and post-stenotic segments. One centimeter into the pre-stenotic segment, the plaque was 432 μm in maximal thickness and occupied 33% of the area within the internal elastic lamina. One centimeter into the post-stenotic segment, the plaque was 463 μm in maximal thickness and occupied 35% of the area within the internal elastic laminae. In the carotid with the recanalized thrombus, there was a plaque with a necrotic core 0.5 cm into the pre-stenotic segment that was 798 μm in thickness and occupied 55% of the area within the internal elastic lamina. In the post-stenotic segment, there was intimal xanthoma (fatty streak) of 351-μm thickness that occupied 6% of the area within the internal elastic lamina.

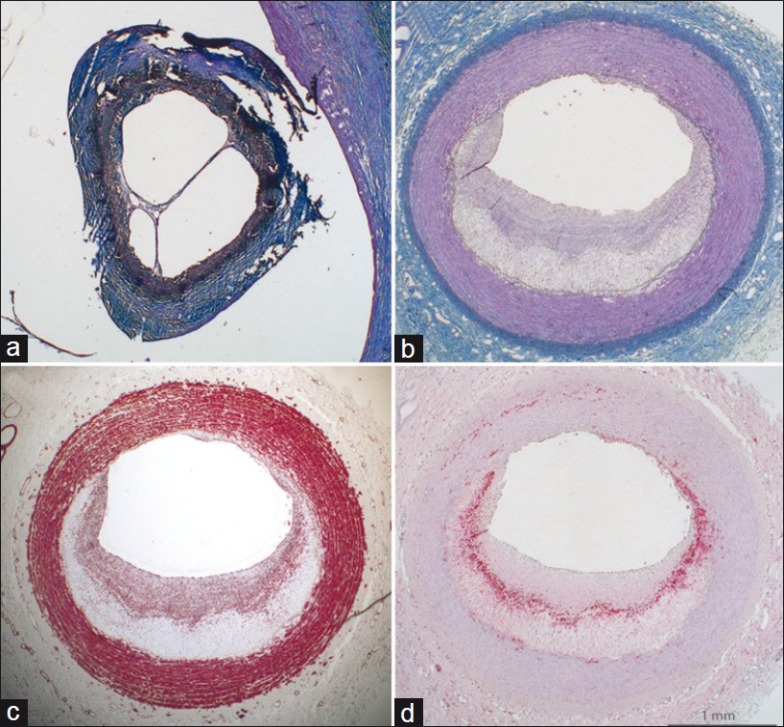

Figure 5.

Microscopic examination of a carotid artery stenosis model in hypercholesterolemic minipigs. (a) The stenosed segments with signs of previous thrombosis. (b), (c) and (d). The plaque proximal to the stenosis. Panels a and b are trichrome-elastin stains (collagen blue, smooth muscle cells red, elastin black). (c) Smooth muscle cell actin stain with smooth muscle cells in the fibrous cap covering the necrotic core (asterisk). (d) Macrophage stain with macrophages at the necrotic core border. The scale bar counts for all panels

In the remaining seven minipigs, the stenosed segments showed no signs of thrombus. In these seven minipigs, the pre-stenotic segments had normal intima or adaptive intimal thickening. In the post-stenotic segments, two had atherosclerotic lesions. One had a 414-μm thick plaque without a necrotic core and one had intimal xanthoma (fatty streak). The remaining five minipigs had normal intima or adaptive intimal thickening in their post-stenotic segments.

Relation between atherosclerotic lesions and angiography, blood flow and shear stress

On MRI, the carotid with the occluded stenotic segment had very low flow and wall shear stress in the pre-stenotic and post-stenotic segments. However, oscillatory wall shear stress was very high (>0.41 in both segments) and there were lesions in both segments.

In the carotid with recanalized thrombus, angiography showed a high stenosis degree (83%) and pronounced post-stenotic dilatation (74%). The wall shear stress was lower in the in post-stenotic segment than in the pre-stenotic segment, and there was more oscillatory shear stress in the post-stenotic segment. There were atherosclerotic lesions in both segments, but a larger more advanced lesion was found in the pre-stenotic segment.

One of the two minipigs with atherosclerosis in the post-stenotic segment did not undergo MRI. Angiographically, this minipig had the largest degree of post-stenotic dilatation indicating that low and oscillatory shear stress may have been present in the post-stenotic segment. The other of the two minipigs with atherosclerosis in the post-stenotic segment, had low wall shear stress and a high degree of oscillatory shear stress observed in the patent carotid arteries in its post-stenotic segment. Notably, the post-stenotic wall shear stress was only one-sixth of the wall shear stress in the pre-stenotic segment in this minipig.

DISCUSSION

In common carotid arteries of hypercholesterolemic minipigs, we evaluated the effects of blood flow and wall shear stress on local development of atherosclerotic plaques, including plaques with necrotic cores that are the key and dangerous characteristic of vulnerable plaques. Atherosclerotic lesions were found in both pre-stenotic and post-stenotic segments of an occluded carotid and a carotid with recanalized thrombus. In patent carotid arteries, two post-stenotic segments had atherosclerotic lesions, whereas no pre-stenotic segments had atherosclerotic lesions.

The relation between local plaque development and angiography, blood flow and shear stress

It has previously been reported that hypercholesterolemic mice and pigs develop atherosclerotic lesions in response to perivascular collar placement.[6–13] In such studies, stenosis evaluation with flow measurements and angiography is not consistently performed. For the first time, we assessed carotid artery flow and geometry with MRI and described local wall shear stress with computational fluid dynamics on this basis. With this detailed description of wall shear stress, we were able to make two interesting observations that at least partially contradict common assumptions.

Firstly, it is often emphasized that the pre-stenotic segment has low endothelial shear stress and this is used to substantiate that low shear stress promotes plaque development and a vulnerable plaque phenotype.[6] However, we found that endothelial shear stress tended to be even lower in the post-stenotic segment than in the pre-stenotic segment. This is in agreement with the observed post-stenotic dilatation. With the same volumetric flow in the pre-stenotic and post-stenotic segments, linear blood flow velocities and endothelial shear stress should be lower in a dilated post-stenotic segment. Also, we found that the low post-stenotic shear stress was often associated with a high degree of oscillatory stress. Hence post-stenotic lesion development seemed as much linked to a high degree of oscillatory stress as to a low magnitude of wall shear stress.

Secondly, it is often concluded that low shear stress promotes atherosclerotic lesion formation.[5,6] In the present study, we found lesions at locations with the combination of low wall shear stress and oscillatory stress. However, we observed both pre-stenotic and post-stenotic segments without lesions despite the presence low shear stress. These segments were without oscillatory stress. We also observed areas with oscillatory stress and high wall shear stress. These areas, likewise, had not developed lesions. This indicates a combined pro-atherogenic effect of low wall shear stress and a high degree of oscillatory stress that at least exceeds that of low wall shear stress or oscillatory stress alone. The described dependency on oscillatory stress for atherosclerotic lesion development may explain, at least in part, why plaques are found close to the stenosis and not distant from the stenosis, even though the same low shear stress prevails here.

Thrombosis may interfere with interpretation

In stenoses with thrombosis or recanalized thrombosis, interpretation of not only flow, shear and imaging but also of the microscopic examination is more complicated. When a thrombus forms in the stenosed segment, the thrombus may extend into the pre-stenotic and post-stenotic segments. Months later, a reorganized and endothelialized thrombus may be difficult to discern from a plaque as it can contain the same components, i.e., fibrous tissue, macrophage foam cells, smooth muscle cells, extracellular lipid, red blood cells or their remnants and calcifications.[23,24] Strands of tissue taking off from the plaque into the lumen, and maybe even connecting with the opposite wall as a septum crossing the lumen, should raise the suspicion of reorganized thrombus.

Also, when a thrombus occludes the stenosed segment but the pre-stenotic and post-stenotic segments remain patent as described here, there is no bulk flow in the artery and the blood flow more resembles waves washing on a beach. This leads to a low and oscillatory shear pattern as our results demonstrate. If the occlusion of the stenosed segment is not recognized and patency is re- established by recanalization, this may lead to biased conclusions. In this study, we identified an occlusion by imaging and confirmed this finding by microscopic examination, whereas the recanalized thrombus was only identified by microscopic examination of sections from the stenosed segment.

Thrombosis may give rise to local lesion development through temporary or permanent occlusion leading to marked alterations of flow and shear stress, or by reorganization of thrombus. In mice, complete flow cessation induced by carotid ligation leads to lesion formation beneath an intact endothelium and without thrombosis. The underlying mechanisms are being studied.[25–28] In humans, the contribution of thrombus to the volume of existing plaques and its organization is well-described.[23,24]

Limitations

This study was of a relatively short duration, and a higher number of lesions and more advanced lesions may have developed over a longer study period. Although flow changes were measured perioperatively, it would be preferable to study the minipigs also with ultrasound and MRI earlier to further elucidate the effects of flow on lesion development in this model. The number of minipigs included in this study was limited, so although the study contains some interesting findings that can generate ideas and hypothesis regarding wall shear stress and atherosclerotic plaque development, it did not have the power to test or prove hypotheses.

A number of assumptions used in computational fluid dynamics introduce limitations to the interpretation of the link between shear stress and lesion development. E.g., we used the common assumption that arterial compliance could be neglected. However, arterial deformation by the pulse wave, especially as it suddenly meets a severe stenosis, may have effects on atherogenesis. These could also be part of the explanation for the observation that lesions preferentially form close to a surgically induced stenosis.

CONCLUSION

In hypercholesterolemic minipigs, we induced common carotid blood flow changes with a perivascular collar and describe effects of common carotid blood flow and wall shear stress on the development of atherosclerotic lesions. Atherosclerotic lesions were found in both pre-stenotic and post-stenotic segments of a thrombosed carotid and a carotid with recanalized thrombosis. In patent carotid arteries, atherosclerotic lesions were found in the post-stenotic segments only, and development of atherosclerotic lesion development seemed dependent on the simultaneous presence of both low and oscillatory shear stress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Birgitte Kildevæld Sahl, Lisa Maria Røge, and Dorte Wilhardt Jørgensen for their expert technical assistance in preparation of the histology.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Falk E, Shah PK, Fuster V. Coronary plaque disruption. Circulation. 1995;92:657–71. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falk E. Pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:C7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thim T, Hagensen MK, Bentzon JF, Falk E. From vulnerable plaque to atherothrombosis. J Intern Med. 2008;263:506–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spagnoli LG, Mauriello A, Sangiorgi G, Fratoni S, Bonanno E, Schwartz RS, et al. Extracranial thrombotically active carotid plaque as a risk factor for ischemic stroke. JAMA. 2004;292:1845–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.15.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatzizisis YS, Jonas M, Coskun AU, Beigel R, Stone BV, Maynard C, et al. Prediction of the localization of high-risk coronary atherosclerotic plaques on the basis of low endothelial shear stress: An intravascular ultrasound and histopathology natural history study. Circulation. 2008;117:993–1002. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.695254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng C, Tempel D, van HR, van der BA, Grosveld F, Daemen MJ, et al. Atherosclerotic lesion size and vulnerability are determined by patterns of fluid shear stress. Circulation. 2006;113:2744–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.590018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von der Thusen JH, van Berkel TJ, Biessen EA. Induction of rapid atherogenesis by perivascular carotid collar placement in apolipoprotein E-deficient and low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Circulation. 2001;103:1164–70. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.8.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bentzon JF, Weile C, Sondergaard CS, Hindkjaer J, Kassem M, Falk E. Smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis originate from the local vessel wall and not circulating progenitor cells in ApoE knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2696–702. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000247243.48542.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bentzon JF, Sondergaard CS, Kassem M, Falk E. Smooth muscle cells healing atherosclerotic plaque disruptions are of local, not blood, origin in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Circulation. 2007;116:2053–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.722355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishii A, Vinuela F, Murayama Y, Yuki I, Nien YL, Yeh DT, et al. Swine model of carotid artery atherosclerosis: Experimental induction by surgical partial ligation and dietary hypercholesterolemia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:1893–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi ZS, Feng L, He X, Ishii A, Goldstine J, Vinters HV, et al. Vulnerable plaque in a Swine model of carotid atherosclerosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:469–72. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reitman JS, Mahley RW, Fry DL. Yucatan miniature swine as a model for diet-induced atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 1982;43:119–32. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(82)90104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerrity RG, Natarajan R, Nadler JL, Kimsey T. Diabetes-induced accelerated atherosclerosis in swine. Diabetes. 2001;50:1654–65. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.7.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalager S, Paaske WP, Kristensen IB, Laurberg JM, Falk E. Artery-related differences in atherosclerosis expression: Implications for atherogenesis and dynamics in intima-media thickness. Stroke. 2007;38:2698–705. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.486480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalager S, Falk E, Kristensen IB, Paaske WP. Plaque in superficial femoral arteries indicates generalized atherosclerosis and vulnerability to coronary death: An autopsy study. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng C, Helderman F, Tempel D, Segers D, Hierck B, Poelmann R, et al. Large variations in absolute wall shear stress levels within one species and between species. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195:225–35. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thim T. Human-like atherosclerosis in minipigs: A new model for detection and treatment of vulnerable plaques. Dan Med Bull. 2010;57:B4161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thim T, Hagensen MK, Drouet L, Bal dit SC, Bonneau M, Granada JF, et al. Familial hypercholesterolaemic downsized pig with human-like coronary atherosclerosis: A model for preclinical studies. EuroIntervention. 2010;6:261–8. doi: 10.4244/EIJV6I2A42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thim T, Hagensen MK, Wallace-Bradley D, Granada JF, Kaluza GL, Drouet L, et al. Unreliable assessment of necrotic core by virtual histology intravascular ultrasound in porcine coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:384–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.919357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laustsen J, Pedersen EM, Terp K, Steinbruchel D, Kure HH, Paulsen PK, et al. Validation of a new transit time ultrasound flowmeter in man. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996;12:91–6. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(96)80282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicolaides AN, Shifrin EG, Bradbury A, Dhanjil S, Griffin M, Belcaro G, et al. Angiographic and duplex grading of internal carotid stenosis: Can we overcome the confusion? J Endovasc Surg. 1996;3:158–65. doi: 10.1177/152660289600300207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Falk E, Fallon JT, Mailhac A, Fernandez-Ortiz A, Meyer BJ, Weng D, et al. Muramidase: A useful monocyte/macrophage immunocytochemical marker in swine, of special interest in experimental cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Pathol. 1994;3:183–9. doi: 10.1016/1054-8807(94)90028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mann J, Davies MJ. Mechanisms of progression in native coronary artery disease: Role of healed plaque disruption. Heart. 1999;82:265–8. doi: 10.1136/hrt.82.3.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burke AP, Kolodgie FD, Farb A, Weber DK, Malcom GT, Smialek J, et al. Healed plaque ruptures and sudden coronary death: Evidence that subclinical rupture has a role in plaque progression. Circulation. 2001;103:934–40. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.7.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar A, Lindner V. Remodeling with neointima formation in the mouse carotid artery after cessation of blood flow. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:2238–44. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.10.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi ET, Khan MF, Leidenfrost JE, Collins ET, Boc KP, Villa BR, et al. Beta3-integrin mediates smooth muscle cell accumulation in neointima after carotid ligation in mice. Circulation. 2004;109:1564–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121733.68724.FF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moura R, Tjwa M, Vandervoort P, Cludts K, Hoylaerts MF. Thrombospondin-1 activates medial smooth muscle cells and triggers neointima formation upon mouse carotid artery ligation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2163–9. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.151282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sommerville LJ, Kelemen SE, Autieri MV. Increased smooth muscle cell activation and neointima formation in response to injury in AIF-1 transgenic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:47–53. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.156794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]