Abstract

In India, under the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program (RNTCP), the percentage of smear-positive re-treatment cases is high. The causes of re-treatment include relapse of the disease after successful completion of treatment, treatment failure, and default in treatment. RNTCP does not follow up the patients for any period of time after successful completion of treatment to determine whether they relapse. Given the high cost of treatment for each patient under RNTCP and the potential for spread of disease from these patients, it is crucial for the success of the program and control of the disease in the country to find out more about the reasons behind this. T0 o conduct a systematic review of literature and determine evidence regarding recurrence of TB after its successful treatment with standard short course chemotherapy under DOTS guidelines. T0 en databases were searched including Medline, Cochrane database, Embase and others and reference lists of articles. 255 papers resulted from these searches. Seven studies were finally included in the review after applying the inclusion, exclusion and quality assessment criteria. R0 elapse rate is high (almost 10%) in India which is higher than international studies. Majority of relapse cases present soon after completion of treatment (first six months). Risk factors for relapse included drug irregularity, initial drug resistance, smoking and alcoholism Sex and weight were not risk factors in India. The outcome of relapse cases put on treatment is positive but less effective than new cases. There are sound arguments and sketchy evidence that DOTS Category 2 treatment may not be adequate for retreatment patients.

KEY WORDS: Directly observed therapy, India, relapse, Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

In India, under the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program (RNTCP), the percentage of smear-positive re-treatment cases out of all smear-positive cases is 24%.[1] The causes of re-treatment include relapse, failure, and default in treatment. RNTCP does not follow up the patients for any period of time after successful completion of treatment to determine whether they relapse. Given the high cost of treatment for each patient under RNTCP and the potential for spread of disease from these patients, it is crucial for the success of program and control of the disease in the country to find out more about the reasons behind this.

Strong evidence regarding the usefulness of Directly Observed Treatment Short course (DOTS) with respect to relapse would, ideally, need a well-designed randomized controlled trial. But this is considered unethical by some authors given the positive experience from it in practice settings.[2] Thus, an attempt is being made in this paper to find out more about these aspects of the tuberculosis (TB) control program in India by reviewing the existing evidence from published studies by the method of a systematic review.

Due to the fact that India has the maximum number of cases and highest burden of TB of any country in the world, accounting for one-fifth of global incidence, an effective TB control program in India is essential to, and will have global implications in, the international TB control effort. The neglected state of health in the country, the deficiencies in the system, the sheer variety of providers, and the number of patients make India an appropriate setting for this study. The high recurrence rates encountered in clinical practice along with the relative lack of published research prompted the author to embark on this study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The research question was “Do TB patients who have successfully completed treatment on DOTS-based guidelines have lower relapse rates than those on non-DOTS-based treatments.” This was broken down into these objectives:

To conduct a systematic review of literature and determine the strength and sufficiency of evidence regarding recurrence/relapse of TB after successful treatment with standard 6-month treatment regimen

To discuss other factors that influence re-treatment under RNTCP in India

To identify key aspects of further research in this area.

The definitions used in this study are from the RNTCP. Relapse is defined as a TB patient who was declared cured or treatment completed by a physician, but who reports back to the health service and is now found to be sputum smear positive. Failure, by definition, is any TB patient who is smear positive at 5 months or more after starting treatment. Failure also includes a patient who was treated with Category III regimen but who becomes smear positive during treatment. And treatment after default is a TB patient who received anti-tuberculosis treatment for 1 month or more from any source and returns to treatment after having defaulted, i.e., not taken anti-TB drugs consecutively for 2 months or more, and is found to be sputum smear positive.

Ethics approval of this study was not required as it was a secondary research, but an ethics declaration was made.

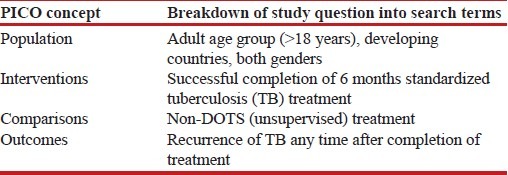

An initial scoping search was conducted in Ovid-MEDLINE database. Use of study questions was made for guidance in identification of search terms. Scoping search was intended to get an idea of the standard and quantity of available studies on this topic. Use of scoping search was also made for identification of appropriate search terms for the main search. The Population Intervention Comparator Outcome (PICO) concept was made use of in dividing the study question into its four constituent components [Table 1].

Table 1.

Detailed breakdown of PICO components for this study

The preliminary search was too broad with a huge number of results. With the intention of not missing out on any potentially relevant articles, search terms were enlisted for each study question (and its subparts) by using a combination of both Medical Subject Headings terms and keywords. These search terms were utilized in searching the Ovid-MEDLINE database. Word truncation was also made use of to improve sensitivity and avoid missing important papers.

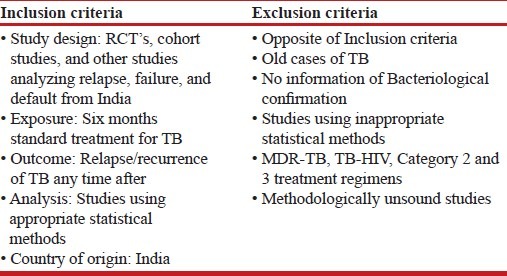

As no restrictions were used in the initial scoping search, this resulted in numerous articles. Consequently, during later searches, restriction terms based on inclusion and exclusion criteria were added to limit the number of results [Table 2]. Some publication types not considered suitable for this review included economic evaluations, medical record reviews, editorials, and journal letters.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Search strategy

A large number of electronic databases were searched to ensure that relevant articles are identified and included in this systematic review. This was attempted in order to not miss any potentially relevant article. These included Ovid-MEDLINE, The Cochrane library, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Social sciences citation index, ASSIA, ERIC, Embase, and sociological abstracts.

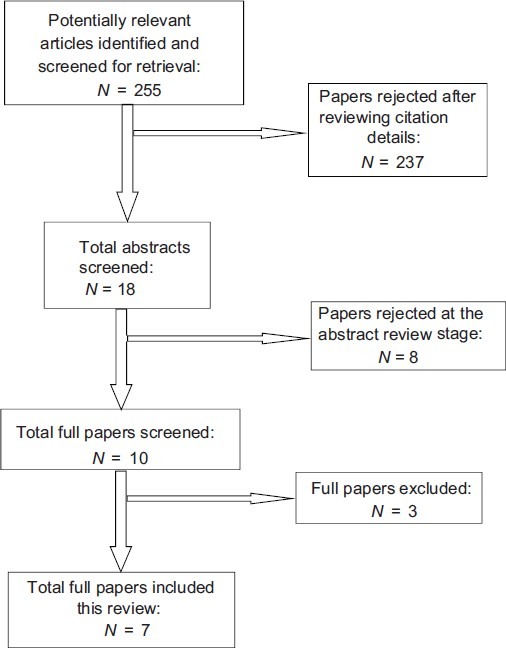

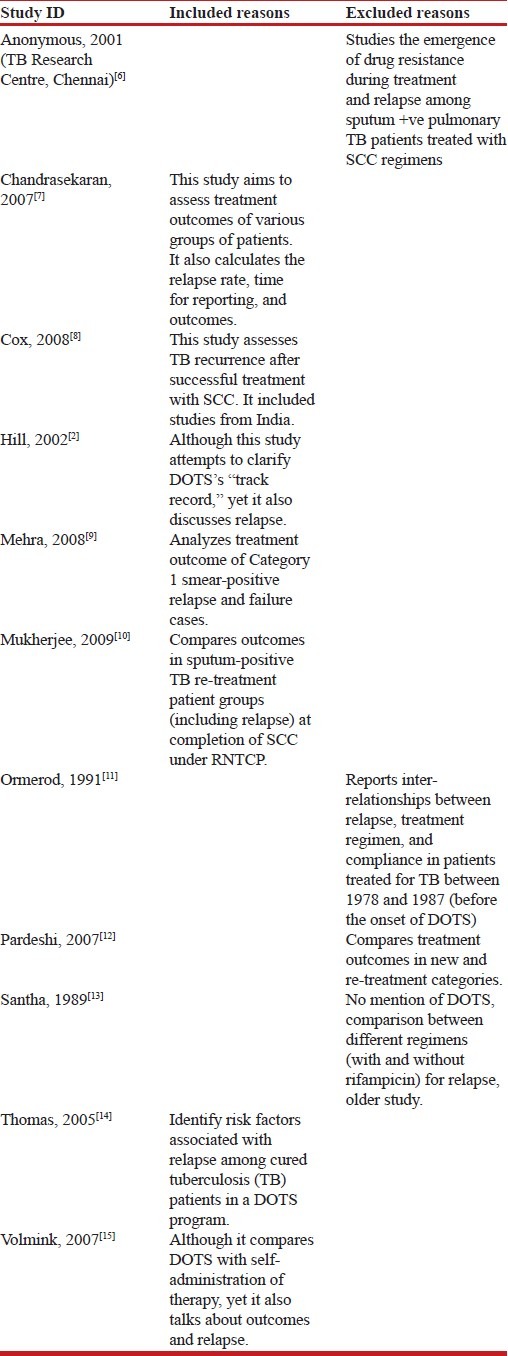

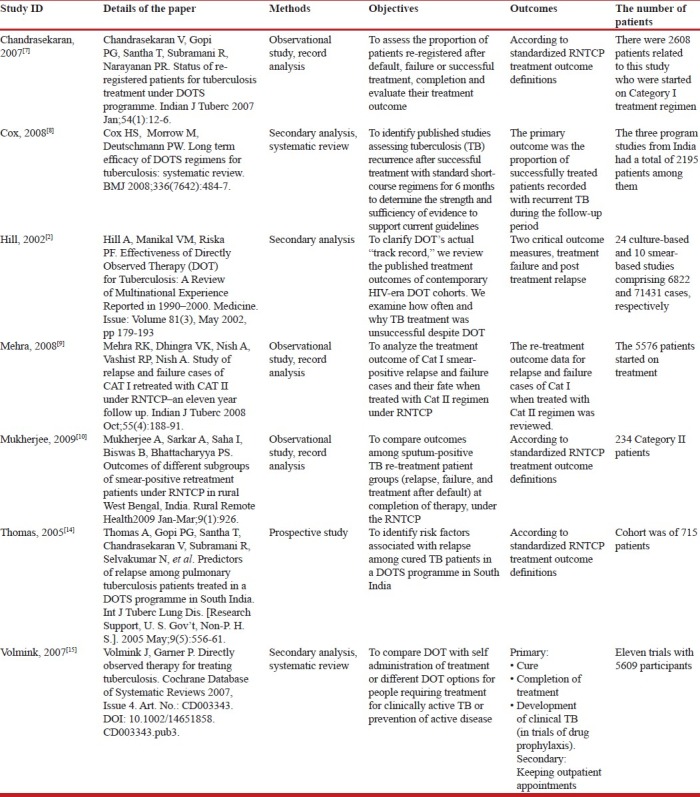

An estimate was made that the relevant articles could be there in both medical and sociological databases. Thus, the chosen databases reflect an attempt to cover both medical (clinical, nursing) and sociological sources of research. Grey literature search and hand searching was not done due to time and feasibility constraints. This was assumed not to have a bearing on the process of study selection as good quality studies are published in indexed journals, which are available online. The process of identification of relevant publications is highlighted in Figure 1. Reasons for inclusion and exclusion of studies are listed in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Process of identification of relevant publications

Table 3.

Reasons for included and excluded studies

Data extraction

For quality appraisal purposes in this review, a checklist from CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Program) was employed. For this study, if the retrieved studies corresponded with these two questions, they were considered as potentially relevant.

An attempt was made to minimize this bias by developing a data extraction form before the searches were done [Table 4]. A sample of this form was made while drawing the study protocol.

Table 4.

Data extraction form

RESULTS

The findings of included studies are discussed here. A narrative synthesis instead of meta-analysis has been attempted. Reasons for not performing meta-analysis were twofold firstly, due to the considerable heterogeneity of data, it was not possible to combine them statistically, and secondly, that majority were observational studies in this review where statistical combination of data is usually not a prominent component.

Use of terminology and methodology

Although under DOTS there are standard definitions of various treatment categories and outcomes, yet the use of these definitions and terms was inconsistent in different studies. As an example: Thomas 2005 used a more stringent definition of relapse than what is used in RNTCP, but he considers that definition to be less stringent than what is used in randomized controlled trials (RCTs). He defines a relapse case as a patient cured under DOTS who has two sputum samples positive for acid fast bacilli by smear, culture, or combination of both. This has a direct bearing on his results because the rate varies, 12.3% according to his definition and 10% according to RNTCP definition.

There were also different types of studies included in this review including prospective, program-based observational studies, literature, and systematic reviews. These studies were from different settings, which varied between the north–south and rural–urban parts of the country. While some studies were prospective, the majority were from program conditions. Only those studies from reviews were included which had been done in India. However, considering that India is a huge country, these are considerable variations among the studies, e.g.: Mehra,[9] is from a predominantly urban area in North India (Gulabi Bagh Chest Clinic, Delhi) while Chandrasekaran 2006 is from a rural area in South India (Tiruvallur, Tamil Nadu). This may have a bearing on results as the Category 1 relapse cases started on Category 2 in the former are 9% while in the latter are 6.5%.

The observation period for relapse also varied in different studies. While Thomas[14] followed up his patients for 18 months, other studies (Mehra,[9] Mukherjee 2009,[10] and Chandrasekaran 2006) do only not specify a clear follow up period but rather that the data analyzed was from a time frame of 11, 6.5, and 5.5 years, respectively.

Anti-TB treatment under the RNTCP is given intermittently thrice weekly but those seeking the treatment for the same condition outside the program are more likely to have received a non-intermittent therapy. Although the bulk of evidence supports RNTCP that intermittent therapy is as good as regular treatment, yet there is also some conflicting evidence that this may not be the case.[3,4] It is not clear in some of the studies whether the treatment given is intermittent or not. It was assumed that all studies under RNTCP were using intermittent therapy. Some studies (Cox,[8] Hill[2]) have included all types of therapies, both intermittent and daily. Thus, possible difference between intermittent and daily regimens may be very important, however, they are very poorly documented.

Diagnosis was smear and also culture based. While most of studies (Mehra,[8] Mukherjee[10] and Chandrasekaran 2006) used sputum smear microscopy for diagnosis, some (Cox[8] and Thomas[14]) also used sputum culture along with smear microscopy for diagnosis. Hill 2002 separated the two into different groups and analyzed them separately.

In some of the studies, it has not been made clear about the differences between relapse and re-infection. Attempts were not made to diagnose re-infection, and this re-infection may be misinterpreted as a failure to eradicate the initial strain. There is a likelihood of this re-infection having falsely increased the apparent relapse rate, especially in high prevalence settings and HIV-positive people.

Summary of study findings

In the seven studies, three were reviews (Cox,[8] Hill,[2] Volmink[15]), one was a prospective study (Thomas[14]), and the rest three (Chandrasekaran 2006, Mehra,[9] Mukherjee[10]) were record-based studies under program conditions of RNTCP. These seven included studies will be discussed in the following section under two headings–relapse and other findings.

Relapse

As mentioned in the introduction, re-treatment cases constitute about 24% of all cases in RNTCP. These include relapse, failure, and treatment after default. Given the high human and drug cost of treatment of each patient (especially in the re-treatment group), more information and subsequent reduction of patients in this group is critical to the success of TB control activities. And as the patients in RNTCP are not followed up after treatment for any length of time, there is very less information about relapse. There seems to be no trend from year to year that the proportion of re-treatment cases becomes reduced as DOTS has now been consolidated.[1]

The relapse rate was high in almost all the studies. Only Thomas[14] actively followed up the patients and found the relapse rate to be 12.3% using his stricter definition, while the rate was 10% using the RNTCP definition. Other researchers (Chandrasekaran 2006, Mehra[9]) reported only those patients who had presented themselves (passively) and their relapse rates were 6.5% and 9%, respectively. Cox[8] also found relapse rates of more than 10% in two studies from India.

There were differences in relapse rates for national and international studies. Compared to around 10% relapse rates in studies from India, the international studies showed an average relapse rate of 3.6 and in 21 culture-based and 3.2 and 3.3% in two smear-based studies (Hill[2]). Cox[8] also found considerable variations in recurrence rates from 0 to 14% in studies from around the world.

Risk factors for relapse included drug irregularity, initial drug resistance, smoking, and alcoholism; age, sex, and weight had no influence (Thomas[14]). Cox[8] also listed potential contributors to recurrent TB as shorter total duration of treatment (particularly rifampicin), poor adherence during treatment (mainly during intensive phase), use of fewer than three drugs in intensive phase, greater disease severity and cavitation, high bacterial load, smoking, being male, the presence of concomitant disease, being underweight, and infection with HIV.

The time of presentation of relapse also varied. But the majority (68.5%) of relapse occurred in the first year and 50% of total relapses were in the first 6 months of completion of treatment (Mehra[9]). Thomas[14] also found that 91.9% of the 62 relapses were within the first year and 77.4% were within the first 6 months. The period of observation in these two studies was different (11 years and 1.5 years, respectively), but it is obvious that the majority of relapses occur within the first year of successful completion of treatment. Similarly, Chandrasekaran 2006 found 91% of his patients were re-registered within 2 years and median interval between declaring the treatment outcome and re-start of treatment was 212 days (approximately 7 months) for relapse patients.

The outcome of relapse patients who were put on therapy was positive in the majority of cases. Mehra[9] and Mukherjee[10] report 76.4% and 76.35%, respectively, of their relapse patients put on therapy as having a positive outcome (cured or treatment completed). But this was not the case for other categories of re-treatment regimen (failure and default), which had worse treatment outcomes (discussed later). Even so, the outcome of re-treatment of relapse cases is poorer than Category 1 patient outcome.

Volmink[15] argues that DOTS is not recommended for re-treatment patients, as re-treatment patients assigned to DOTS group had a worse treatment outcome than those in self-administration of treatment group. However, the sample size of the concerned study is too small to be conclusive.

Other findings

On comparison of DOTS and non-DOTS based treatment of TB, Volmink[15] concludes that there is no statistically significant difference between the two treatment groups in terms of cure or treatment completion. Hill[2] also admits that superiority of DOTS over unsupervised therapy for routine TB care has not yet been shown in an evidence-based fashion. But most authorities are convinced that DOTS improves treatment effectiveness, drug resistance rates, and overall TB control. His contention is that it is not better only in suboptimal settings, indicating that the program quality must be strong for it to yield its optimal benefits. There might also be an issue of publication bias in favor of DOTS.

Of the new smear-positive patients registered under Category 1, the default and failure rates were 12% and 5%, respectively, in the study by Chandrasekaran 2006 and 16% and 4%, respectively, in the study by Thomas[14]. Mehra[9] recorded a failure rate of 3.4%. The distribution of default and failure cases in Category 2 patients was 22% and 14%, respectively, in the study by Mukherjee.[10] Hill,[2] in his review of studies from around the world, calculated an average failure rate (un-weighted mean±SD) to be 2.4%±2.2% for 21 culture-based studies and 2.5%±1.7% for nine smear-based studies. The combined rate of failure plus default was 11.1%±6.7% (n=20) and 10.0%±7.5% (n=9) in culture- and smear-based studies, respectively. These findings are comparable to findings from India.

The re-treatment outcomes for default and failure cases were not as good as relapse. Mukherjee[10] found 55.88% and 53.85% cases have a favorable outcome on re-treatment in the two categories, respectively. Similarly, Mehra[9] also found that only 48.8% cases of treatment failure on restarting therapy had a favorable outcome. These results are similar to RNTCP treatment cohorts.

Information about drug susceptibility was not given in most of the studies. Low drug resistance patterns in the country suggest its minimal role in causing unfavorable outcomes. However, the role and impact of isoniazid resistance (which is increasing over time[5]) may be significant, as the continuation phase of four months is reduced to effective mono-therapy in these cases. Drug resistance was found to be present in 20% cases of relapse by Thomas.[14]

DISCUSSION

Strengths and limitations

Although TB is a focus of many international activities and a number of national and international organizations are working on its control, yet the results of this systematic review study show that there is a shortage of evidence related to the effectiveness of DOTS versus self-administered treatment as such and also a lack of precise knowledge about the extent of relapse under program conditions in India. There are only seven relevant publications, which were found for this systematic review study. The number of relapse cases is registered in the statistics of the RNTCP of India. Yet, there is no proper routine follow-up of TB patients after end of treatment that will allow a precise idea of the size of the relapse problem.

This is one reason why there is a lack of publications, which investigate this topic. Initial scoping searches revealed a number of publications on TB, but on closer inspection most of them could not fulfill the inclusion criteria and were not included.

Changes in definition of relapse by RNTCP in 2005 also made it difficult to compare old and new studies. The earlier definition recognized that relapses could only occur after cure while the later definition noted that they could happen after successful treatment completion also. Despite these different definitions, the author has attempted to analyze using one standard definition.

Compared to other studies outside India, it is obvious that the choice in India of intermittent regimen may play an important role in the creation of relapse cases compared to daily regimens in many other countries. The issue of choice between an intermittent and a daily treatment regimen has been a subject of much deliberation. It seems likely that a daily regimen might have lower relapse rates compared to an intermittent regimen. However, only proper well-designed prospective randomized studies may answer this query.

Some characteristics of the Indian health system also might have played a part in determining relapse rates. Vast majority of treatment providers are in the private sector. There is a choice of providers for the patient and he is free to discontinue and start treatment from whichever provider he likes, based on his perception of getting benefit for treatment. Also, there are financial incentives for providers from pharmaceutical companies for prescribing various drugs, which sometimes are at odds with ethical principles. Thus, patients can be over treated or started with intensive phase again when they switch providers. This previous treatment history is also poorly documented and may be a source of bias. It has been recorded that patients turn up at RNTCP after shopping for a number of providers in the private sector. It might be happening that many TB re-patients (e.g., those coming from the private sector and now opting for treatment in the public sector) may see an advantage in not reporting previous treatment, in order to escape with a lighter 6-month instead of a more punishing 8-month treatment regimen.

There is also a striking absence of good qualitative studies that are at variance to register-based studies may cast light over the preferences, adherence, and felt problems of the clients of the RNTCP. Without understanding the wishes and the problems seen from the patients, it may be difficult to modify a strategy so strongly advocated by the WHO and many other international organizations working with TB.

Systematic reviews of public health interventions are in themselves methodologically challenging due to use of non-standard terminology and extensive heterogeneity. This was the reason for performing a narrative synthesis instead of meta-analysis in this review. There is a strong likelihood of bias in observational studies.

Some other limitations were that the reviewers looked for evidence only in India. If evidence from other countries were also included, international comparisons would have been very interesting to observe. However, with some 1.2 million TB patients being treated in India annually in the public sector under the RNTCP, India accounts for roughly 20% of the global TB burden. Thus, this study represents a large proportion of TB patients and consequently the findings would have an impact on this great number of patients. There is a possibility that some papers have been missed. Also, there are smaller journals, which are not indexed (at all or in major international electronic databases) and articles in these journals are likely to be missed. Conference proceedings also could not be searched for this review.

Implications for future research and clinical practice

Lack of a common framework for data collection and analysis is an indicator for the need of performing more studies so that the differences can be better understood and methodologies evolved. This would make the comparisons for public health interventions easier. The importance of relapse and its implications in successful implementation of any TB control program using the DOTS strategy should be a point of concern for further research and should be accorded due attention in program documentation and research. As discussed in the section above, the choice in India of intermittent regimen may play an important but unknown role in the creation of relapse cases compared to daily regimens in many other countries. However, only a proper, well-designed, prospective, randomized study may answer this question. Treatment preferences and patient behavior in a complex multi-provider healthcare system like India can be better understood by qualitative studies supplementing the proposed randomized studies. International comparisons might prove to be useful for governments for making changes in existing strategies. Role of HIV, Multi Drug Resistant (MDR) TB, re-infection with a different strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and outcomes in the pediatric age group also need to be investigated for relapse.

CONCLUSIONS

Relapse rate is high (almost 10%) in almost all the studies from India. It is higher than those found in international studies. The risk factors for relapse include drug irregularity, initial drug resistance, smoking, and alcoholism. Sex and weight have been found to be significant in international studies but not in India. Majority of relapses presented in the first year after completion of treatment, and the bulk of it occurs in the first 6 months itself. The outcome of relapse patients put on treatment is positive in terms of cure in the majority of cases but clearly less effective then the results of DOTS for new TB cases never treated before. And there are sound arguments and some sketchy evidence that DOTS Category 2 treatment may not be adequate for re-treatment patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author is grateful for the support offered to him by School of Public Health, University of Copenhagen, and also the School of Health and Related Research, University of Sheffield.

Dr. Alan A J O’Rourke from ScHARR in the University of Sheffield and Dr. Sören Thybo in the Department of Infectious Diseases, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, and the University of Copenhagen.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Directorate General of Health Services. New Delhi: MOHFW GoI; 2009. Central TB Division, TB India 2009 RNTCP status report, in TB India. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill AR, Manikal VM, Riska PF. Effectiveness of directly observed therapy (DOT) for tuberculosis: A review of multinational experience reported in 1990-2000. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002;81:179–93. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mwandumba HC, Squire SB. Fully intermittent dosing with drugs for treating tuberculosis in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(4):CD000970. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang KC, Leung CC, Yew WW, Ho SC, Tam CM, et al. A nested case-control study on treatment-related risk factors for early relapse of tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1124–30. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200407-905OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuberculosis Research Centre (ICMR), Chennai. Trends in initial drug resistance over three decades in a rural community in south India. Indian J Tuberc. 2003;50:75–86. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anonymous, Low rate of emergence of drug resistance in sputum positive patients treated with short course chemotherapy. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5:40–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandrasekaran V, Gopi PG, Santha T, Subramani R, Narayanan PR. Status of re-registered patients for tuberculosis treatment under DOTS programme. Indian J Tuberc. 2007;54:12–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox HS, Morrow M, Deutschmann PW. Long term efficacy of DOTS regimens for tuberculosis: Systematic review. Br Med J. 2008;336:484–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39463.640787.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehra RK, Dhingra VK, Nish A, Vashist RP. Study of relapse and failure cases of CAT I retreated with CAT II under RNTCP–an eleven year follow up. Indian J Tuberc. 2008;55:188–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukherjee A, Sarkar A, Saha I, Biswas B, Bhattacharyya PS. Outcomes of different subgroups of smear-positive retreatment patients under RNTCP in rural West Bengal, India. Rural Remote Health. 2009;9:926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ormerod LP, Prescott RJ. Inter-relations between relapses, drug regimens and compliance with treatment in tuberculosis. Respir Med. 1991;85:239–42. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(06)80087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pardeshi GS, Deshmukh D. A comparison of treatment outcome in re-treatment versus new smear positive cases of tuberculosis under RNTCP. Indian J Public Health. 2007;51:237–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santha T, Nazareth O, Krishnamurthy MS, Balasubramanian R, Vijayan VK, Janardhanam B, et al. Treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis with short course chemotherapy in south India–5-year follow up. Tubercle. 1989;70:229–34. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(89)90016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas A, Gopi PG, Santha T, Chandrasekaran V, Subramani R, Selvakumar N, et al. Predictors of relapse among pulmonary tuberculosis patients treated in a DOTS programme in South India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:556–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volmink J, Garner P. Directly observed therapy for treating tuberculosis (Cochrane Review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2:1465–858. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003343.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]