Abstract

Background. Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia in the elderly population. Growing evidence supports that AD patients are at high risk for hip fracture, but the issue remains questionable. The purpose of the present study is to perform a meta-analysis to explore the association between AD and risk of hip fracture. Considering that bone mineral density (BMD) acts as a strong predictor of bone fracture, we also studied the hip BMD in AD patients. Methods. We searched all publications in Medline, SciVerse Scopus, and Cochrane Library published up to January 2012 about the association between AD and hip fracture or hip BMD. Results. There are 9 studies included in the meta-analysis. The results indicate that AD patients are at higher risk for hip fracture (OR and 95% CI fixed: ES = 2.58, 95% CI = [2.03, 3.14]; dichotomous data: summary OR = 1.80, 95% CI = [1.54, 2.11]) than healthy controls. Further meta-analysis showed that AD patients have a lower hip BMD (summary SMD = −1.12, 95% CI = [−1.34, −0.90]) than healthy controls. Conclusions. It was found that in comparison with healthy controls AD patients are at higher risk for hip fracture and have lower hip BMD.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia among the elderly, and its prevalence is expected to rise steadily as the aging population swells [1, 2]. AD patients are at high risk for fractures, particularly of the hip fracture [3, 4]. Hip fracture is a major cause of disability among older people and is associated with more deaths and medical costs relative to all other osteoporosis-related fractures combined [5]. In recent years, there is a growing evidence supporting that patients affected by AD have high incidence of hip fracture [6–8]. We aim to perform a meta-analysis to provide a comprehensive conclusion on the association between AD and risk of hip fracture. Since bone mineral density (BMD) acts as a strong predictor of bone fractures [9], hip BMD levels in AD patients were also investigated to verify the risk of hip fracture in AD patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Information Retrieval

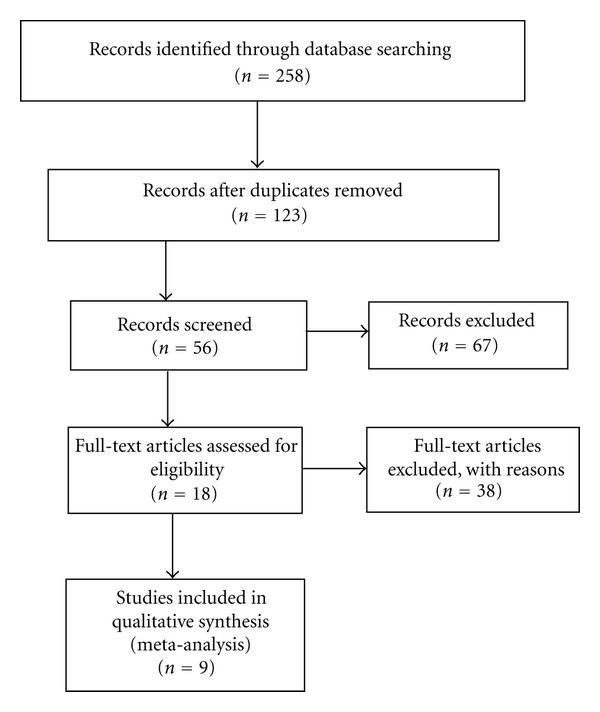

With the following terms: “(Alzheimer's disease and hip fracture) or (Alzheimer's disease and bone mineral density)”, a literature search was conducted in the Medline, Cochrane Library, and SciVerse Scopus databases up to January 2012. The conference proceedings and reference lists from retrieved articles were also reviewed in search of other relevant reports. We used two sets of parameters to analyze the association between AD and risk of hip fracture. The first set of parameters include the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) fixed, and the second set of parameters include the numbers of AD patients, healthy controls, and fracture patients. As to BMD, we needed the numbers of AD patients and healthy controls, the BMD mean, and standard deviation values for both patient and healthy control groups. BMD (mm Al) was measured at the right second metacarpal using a computer-linked X-ray densitometer (CXD) (Teijin, Tokyo, Japan) [10]. In total, 9 studies were finally included in the present meta-analysis (Figure 1), among which, 3 studies (OR and 95% CI fixed) [11–13] and 4 studies (dichotomous data) [11, 12, 14, 15] reported risk of hip fracture in AD patients, and 4 studies [16–19] studied the hip BMD in AD patients.

Figure 1.

Selection of studies for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using the Stata 12.0 statistical software. We used the parameters from each study about 95% CI, OR, the standardized mean difference (SMD), and the effect size (ES). The heterogeneity was evaluated via the I-square test and Chi-square. If the P value was greater than 0.10 and the I2 value was less than 50%, the study was considered not to report significant differences.

3. Results

3.1. Association between AD and Risk of Hip Fracture

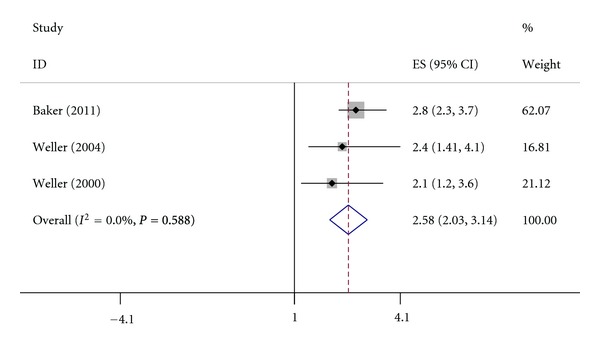

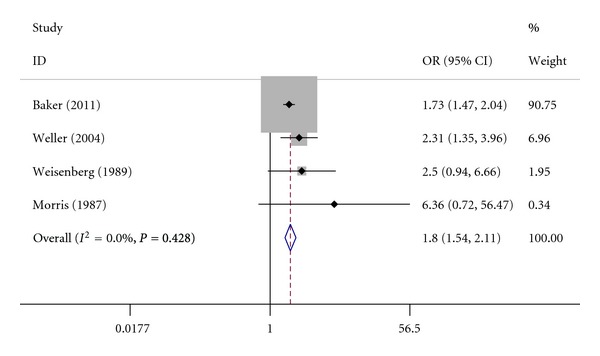

There are 3 studies showing OR and 95% CI fixed and 4 studies showing dichotomous data which met the eligibility criteria. Table 1 shows the first author, year of publication, OR, 95% CI, patient weight, ES, and 95% CI of each study. Table 2 shows the first author, year of publication, number of AD cases and controls, number of hip fracture patients, patient weight, OR, and 95% CI of each study. The country, percentage of women patients, and average patient age of each study were also shown in Table 3. The results of the meta-analysis are shown in Figures 2 and 3, which indicate that AD patients are at higher risk for hip fracture (OR and 95% CI fixed: ES = 2.58, 95% CI = [2.03, 3.14]; dichotomous data: summary OR = 1.80, 95% CI = [1.54, 2.11]) and heterogeneity is not found among these studies (OR and 95% CI fixed: P = 0.588, I2 = 0.0%; dichotomous data: P = 0.428, I2 = 0.0%).

Table 1.

Summary of the studies of the association between AD and hip fracture (OR and 95% CI fixed).

Table 2.

Summary of the studies of the association between AD and hip fracture (dichotomous data).

Table 3.

Country, gender, and mean age of the references included in the meta-analysis of AD and hip fracture.

Figure 2.

Pooled estimate of ES and 95% CI of AD and hip fracture (used OR and 95% CI fixed). ES is represented by squares, whose sizes are proportional to the sample size of the relative study. The whiskers represent the 95% CI. The diamond represents the pooled estimate based on the random effects model, with the centre representing the point estimate and the width the associated 95% CI.

Figure 3.

Pooled estimate of OR and 95% CI of AD and hip fracture (used dichotomous data). OR is represented by squares, whose sizes are proportional to the sample size of the relative study. The whiskers represent the 95% CI. The diamond represents the pooled estimate based on the random effects model, with the centre representing the point estimate and the width the associated 95% CI.

3.2. Association between AD and Hip BMD

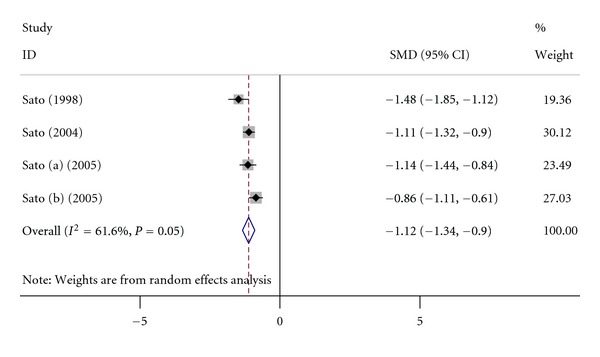

There are 4 studies (including 551 AD patients and 540 controls) reporting the hip BMD level in AD which met the eligibility criteria. Summary of these studies is given in Table 4. The meta-analysis results in Figure 4 indicate that AD patients have a lower hip BMD than healthy controls (summary SMD = −1.12, 95% CI = [−1.34, −0.90]).

Table 4.

Summary of the studies of the association between AD and hip BMD.

| References | N | BMD (mmAl) | Weight (%) | SMD | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | Control | AD | Control | ||||

| [16] | 46 | 140 | 1.738 ± 0.303 | 2.047 ± 0.167 | 19.36 | −1.48 | [−1.85, −1.12] |

| [17] | 205 | 200 | 2.124 ± 0.405 | 2.550 ± 0.360 | 30.12 | −1.11 | [−1.32, −0.90] |

| [18] | 100 | 100 | 1.669 ± 0.324 | 2.000 ± 0.250 | 23.49 | −1.14 | [−1.44, −0.84] |

| [19] | 200 | 100 | 1.885 ± 0.305 | 2.130 ± 0.240 | 27.03 | −0.86 | [−1.11, −0.61] |

Figure 4.

Pooled estimate of SMD and 95% CI of AD and hip BMD (mmAl). SMD is represented by squares, whose sizes are proportional to the sample size of the relative study. The whiskers represent the 95% CI. The diamond represents the pooled estimate based on the random effects model, with the centre representing the point estimate and the width the associated 95% CI.

4. Discussion

As a progressive neurodegenerative disease, the symptoms of AD include progressive loss of memory and cognitive function and apraxia [20]. Hip fracture is associated with considerable disability and loss of independence [21–23]. Recent accumulating studies indicated that both hip fracture and AD patients exhibit many similar conditions such as lower weight, lower vitamin D levels, lower gastrointestinal absorption of calcium, and higher parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels [24–28]. Some studies proposed that AD patients are at high risk for hip fracture [6–8]. This meta-analysis aims to provide a comprehensive evaluation on the association between AD and risk of hip fracture based on the available published references. The results (OR and 95% CI fixed: ES = 2.58, 95% CI = [2.03, 3.14]; dichotomous data: summary OR = 1.80, 95% CI = [1.54, 2.11]) suggest that AD patients are at higher risk for hip fracture. Moreover, it was found that AD patients have a lower hip BMD, a predictor of fracture, than healthy controls (summary SMD = −1.12, 95% CI = [−1.34, −0.90]).

Multiple factors may help to understand the association between AD and risk of hip fracture. It has been widely reported that in comparison with healthy controls AD patients have lower levels of 25(OH)D and calcium [29, 30]. Vitamin D status is an important factor of skeletal integrity, and inadequate serum 25(OH)D level is associated with muscle weakness and increased incidences of falls and fractures [31]. Lower levels of vitamin D and calcium can also induce compensatory hyperparathyroidism, which may further contribute to a reduction in BMD [32]. Thus, it can be inferred that vitamin D and calcium deficiency may be an important factor. In addition, parathyroid hormone (PTH) may act as another important factor. Elevated PTH concentrations are associated with cognitive decline and may increase tissue aluminum loads which is a factor in the pathogenesis of AD [33, 34]. Meanwhile, it has been found that the high intact bone Gla protein and pyridinoline cross-linked carboxyterminal telopeptide of type I collagen with PTH induce compensatory hyperparathyroidism to increase bone turnover to raise the risk of fracture [17].

The present meta-analysis has some limitations. First, many factors including anti-AD drugs, exposure to sunlight, and food intake which may influence the AD progression are not considered in the meta-analysis. Second, the number of studies included in the present study is relatively small. Third, we did not consider AD severity, which can vary the prevalence of hip fracture.

5. Conclusions

To summarize, the meta-analysis indicates that AD patients are at high risk for hip fracture and have lower hip BMD than healthy controls. More efforts are warranted to elucidate the mechanisms underlying these associations.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant nos. 30800184 and 30700113).

References

- 1.Reiman EM, McKhann GM, Albert MS, Sperling RA, Petersen RC, Blacker D. Alzheimer's disease: implications of the updated diagnostic and research criteria. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2011;72(9):1190–1196. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10087co1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballard C, Gauthier S, Corbett A, Brayne C, Aarsland D, Jones E. Alzheimer's disease. The Lancet. 2011;377(9770):1019–1031. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hussain. A, Barer D. Fracture risk in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1995;43(4):p. 454. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb05824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchner DM, Larson EB. Falls and fractures in patients with Alzheimer-type dementia. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1987;257(11):1492–1495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnell O, Gullberg B, Allander E, et al. The apparent incidence of hip fracture in Europe: a study of national register sources. Osteoporosis International. 1992;2(6):298–302. doi: 10.1007/BF01623186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melton LJ, III, Beard CM, Kokmen E, Atkinson EJ, O’Fallon WM. Fracture risk in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1994;42(6):614–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rapp K. People with Alzheimer's disease are at increased risk of hip fracture and of mortality after hip fracture. Evidence-Based Nursing. 2011;14(3):78–79. doi: 10.1136/ebn1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanna B, Roffe E. Prevention of hip fracture in elderly women with Alzheimer disease. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(10):1144–1145. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1144-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camarda R, Camarda C, Monastero R, et al. Movements execution in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Behavioural Neurology. 2007;18(3):135–142. doi: 10.1155/2007/845914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsumoto C, Kushida K, Yamazaki K, Imose K, Inoue T. Metacarpal bone mass in normal and osteoporotic Japanese women using computed X-ray densitometry. Calcified Tissue International. 1994;55(5):324–329. doi: 10.1007/BF00299308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker NL, Cook MN, Arrighi HM, Bullock R. Hip fracture risk and subsequent mortality among Alzheimer’s disease patients in the United Kingdom, 1988–2007. Age and Ageing. 2011;40(1):49–54. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weller I, Schatzker J. Hip fractures and Alzheimer’s disease in elderly institutionalized Canadians. Annals of Epidemiology. 2004;14(5):319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weller II. The relation between hip fracture and Alzheimer's disease in the canadian national population health survey health institutions data, 1994-1995. A cross-sectional study. Annals of Epidemiology. 2000;10(7):p. 461. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weisenberg LB, Gaines J. The increased rate of fractures of the hip and spine in Alzheimer’s patients. Western Journal of Medicine. 1989;151(2):p. 206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris JC, Rubin EH, Morris EJ, Mandel SA. Senile dementia of the Alzheimer’s type: an important risk factor for serious falls. Journals of Gerontology. 1987;42(4):412–417. doi: 10.1093/geronj/42.4.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sato Y, Asoh T, Oizumi K. High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and reduced bone mass in elderly women with Alzheimer’s disease. Bone. 1998;23(6):555–557. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato Y, Kanoko T, Satoh K, Iwamoto J. Risk factors for hip fracture among elderly patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2004;223(2):107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato Y, Honda Y, Hayashida N, Iwamoto J, Kanoko T, Satoh K. Vitamin K deficiency and osteopenia in elderly women with Alzheimer’s disease. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2005;86(3):576–581. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato Y, Kanoko T, Satoh K, Iwamoto J. Menatetrenone and vitamin D2 with calcium supplements prevent nonvertebral fracture in elderly women with Alzheimer’s disease. Bone. 2005;36(1):61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Camarda R, Camarda C, Monastero R, et al. Movements execution in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Behavioural Neurology. 2007;18(3):135–142. doi: 10.1155/2007/845914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanis J, Johnell O, Gullberg B, et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in men from southern europe: the MEDOS study. Osteoporosis International. 1999;9(1):45–54. doi: 10.1007/s001980050115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munger RG, Cerhan JR, Chiu BCH. Prospective study of dietary protein intake and risk of hip fracture in postmenopausal women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1999;69(1):147–152. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richmond J, Aharonoff GB, Zuckerman JD, Koval KJ. Mortality risk after hip fracture. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 2003;17(1):53–56. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200301000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guyonnet S, Nourhashemi F, Reyes-Ortega G, et al. Weight loss in Alzheimer’s disease. Revue de Medecine Interne. 1997;18(10):776–785. doi: 10.1016/s0248-8663(97)89967-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ensrud KE, Cauley J, Lipschutz R, Cummings SR. Weight change and fractures in older women. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1997;157(8):857–863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winograd CH, Jacobson DH, Butterfield GE, et al. Nutritional intake in patients with senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 1991;5(3):173–180. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199100530-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White H, Pieper C, Schmader K, Fillenbaum G. Weight change in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1996;44(3):265–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langlois JA, Harris T, Looker AC, Madans J. Weight change between age 50 years and old age is associated with risk of hip fracture in white women aged 67 years and older. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1996;156(9):989–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pogge E. Vitamin D and Alzheimer’s disease: is there a link? Consultant Pharmacist. 2010;25(7):440–450. doi: 10.4140/TCP.n.2010.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oudshoorn C, Mattace-Raso FUS, Van Der Velde N, Colin EM, Van Der Cammen TJM. Higher serum vitamin D3 levels are associated with better cognitive test performance in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2008;25(6):539–543. doi: 10.1159/000134382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van den Bergh JPW, Bours SPG, van Geel TACM, Geusens PP. Optimal use of vitamin D when treating osteoporosis. Current Osteoporosis Reports. 2011;9(1):36–42. doi: 10.1007/s11914-010-0041-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sato Y, Iwamoto J, Kanoko T, Satoh K. Amelioration of osteoporosis and hypovitaminosis D by sunlight exposure in hospitalized, elderly women with Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2005;20(8):1327–1333. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Björkman MP, Sorva AJ, Tilvis RS. Does elevated parathyroid hormone concentration predict cognitive decline in older people? Aging. 2010;22(2):164–169. doi: 10.1007/BF03324791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shore D, Wills MR, Savory J, Wyatt RJ. Serum parathyroid hormone concentrations in senile dementia (Alzheimer’s disease) Journals of Gerontology. 1980;35(5):656–662. doi: 10.1093/geronj/35.5.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]