Abstract

Talon cusp is a relatively uncommon developmental anomaly characterized by cusp-like projections, usually presenting on palatal/lingual surface of the anterior teeth. This cusp resembles an eagle's talon, and hence the name. Normal enamel and dentin covers the cusp, which may or may not contain an extension of pulp. Presence of this anomalous cusp on the facial surface of an anterior tooth is a rare finding and very few cases have been reported in the literature. In most instances, such cusps are associated with clinical problems such as poor esthetics and caries susceptibility. Management of such cases requires a comprehensive knowledge of the clinical entity as well as the problems associated with it. This case report presents a facial talon cusp on the maxillary left central incisor of a 10 year old boy, which was conservatively treated. Vitality of the affected tooth was maintained and followed up for a period of 1 year.

Keywords: Central incisor, composite veneer, facial talon cusp, fluoride varnish, gradual reduction, selective grinding

Introduction

Development of tooth is a complex process, being divided into 6 morphologic stages and 5 physiologic processes. Any aberration in these stages/processes can result in unique manifestations. Disturbances during morphodifferentiation can result in anomalies like talon cusps, mulberry molars and peg laterals.[1] Talon cusp is an anomalous cusp like structure composed of normal enamel and dentin, and containing varying extension of pulpal tissue. It is named so, as its shape resembles an eagle's talon.[2]

Talon cusp was first recognized by Mitchell[3] in 1892, and described as a prominent accessory cusp like structure on the lingual surface of a maxillary central incisor. Schulze[4] referred to the anomaly as a very high accessory cusp, which may connect with the incisal edge to produce a ‘T’ shaped, or if more cervical, a ‘Y’ shaped crown contour. Stojanowski et al.[5] in 2010 mentioned about the oldest of all talon cusps mentioned in the literature. This archaeological report belonged to the age of “ca. 9500 bp” in the republic of Niger and was about a facial talon cusp on the permanent mandibular canine of an adult male.

Hattab et al.[6] classified talon cusps according to their extent from the cementoenamel junction towards the incisal edge, into 3 types: Type 1 - Talon, Type 2 - Semi talon and Type 3 - Trace talon. This classification grades the anomalous cusp from the most extreme to the slightest form. However, Mayes[7] in 2007 categorized facial talon cusps into 3 stages, starting from the slightest to most extreme forms as follows:

Stage 1 – The slightest form, consisting of slightly raised triangle on the labial surface of an incisor extending the length of the crown, but not reaching the cementoenamel junction or the incisal edge;

Stage 2 – The moderate form, consisting of a raised triangle on the labial surface of an incisor that extends the length of the crown, does not reach the cement enamel junction, but does reach the incisal edge, and can be observed clearly and palpated easily at this stage;

Stage 3 – The most extreme form, consisting of a free form cusp extending from the cementoenamel junction to the incisal edge on the labial surface of an incisor.

Talon cusps occurs with a frequency of 0.04 – 10%, and permanent dentition has been involved 3 times more often than the primary dentition.[8] It has predilection for the maxillary over the mandibular teeth, and males are found to be more commonly affected than females.[9] Normally, talon cusp is seen on the palatal or lingual surfaces of the maxillary or mandibular anterior teeth, and very few cases have been reported about the talon cusps found on the facial tooth surfaces.[9] This paper reports a case of a facial talon cusp on the permanent maxillary left central incisor, which was conservatively treated and followed up for a period of 1 year.

Case Report

A 10 year old boy reported to the department of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry with a chief complaint of an abnormally appearing upper front tooth. His medical and family history was non-contributory. Intraoral examination revealed the presence of an accessory cusp on the facial aspect of the permanent maxillary left central incisor, extending from cementoenamel junction towards the incisal edge (stage 3).[7] The accessory cusp was separated from rest of the crown by a non-carious developmental groove [Figure 1]. An intra-oral periapical (IOPA) radiograph revealed a ‘V’ shaped radio-opaque structure superimposed on the image of the maxillary left central incisor. The extent of radiolucency of the pulp tissue into the cusp could be determined radiographically [Figure 2]. Patient's esthetics was compromised due to the presence of facial talon cusp. Hence, it was decided to carry out selective cuspal grinding, followed by composite veneer placement. The treatment was carried out gradually over a period of 9 months to allow sufficient time for formation of reparative dentin and avoid pulpal exposure. Patient was recalled at every 45 days interval and cuspal reduction was done using a pear shaped bur, followed by fluoride varnish application. By the end of 9 months, the cusp was almost completely eliminated without causing pulpal exposure [Figure 3]. Direct composite veneer was placed for better esthetics [Figure 4]. Patient had been followed up over a period of 1 year; and, the tooth was found to be completely asymptomatic with vitality intact at each follow up. The follow-up IOPA radiograph showed healthy periapical tissues with the treated tooth and continued root formation of the maxillary left lateral incisor [Figure 5]. The patient was then referred to the department of Orthodontics for the correction of buccally erupting permanent canines.

Figure 1.

Intraoral view showing facial talon cusp on maxillary left central incisor and showing that the accessory cusp was separated from rest of the crown by a non-carious developmental groove

Figure 2.

Preoperative intra oral periapical radiograph of 21, showing a ‘V’ shaped radio-opaque structure superimposed on the image of the maxillary left central incisor

Figure 3.

Talons cusp of 21 of the patient in the case report seen to be completely eliminated without pulp exposure, and showing reparative dentin formation

Figure 4.

Direct composite veneer placed on the maxillary left central incisor

Figure 5.

Follow-up intra oral periapical radiograph of 21 showing healthy periapical tissues with the treated tooth and continued root formation of the maxillary left lateral incisor

Discussion

Etiology for the formation of the talon cusp is unknown. However, it has been suggested that, it may be due to the combination of genetic and environmental factors and hyperactivity of the dental lamina early in odontogenesis.[10] Developmentally, talon cusp may be formed due to the outer folding of the inner enamel epithelial cells, and transient focal hyperplasia of the peripheral cells of the mesenchymal dental papilla.[8,9] Although talon cusp has not been reported as an integral part of any specific syndrome/anomaly, it appears to be more prevalent in patients with Sturge-Weber syndrome, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, Mohr syndrome, Ellis-van Creveld syndrome, Berardinelli-Seip syndrome, incontinentia pigmenti achromians or patients with cleft lip and palate.[2,8,11–15] Such an association was not seen in the presented case. Talon cusp usually occurs on the palatal or lingual surfaces of the anterior teeth, with very few cases reported on the facial tooth surface.[9] Table 1 and 2 summarize the cases of facial talon cusps reported in the literature. In contrast to the palatal talon cusp, the facial talon cusp shows higher prevalence in females. Including the present report, there were 21 clinical cases reported, having exclusive facial talon cusps, out of which 19 were in the permanent dentition and 2 in the primary dentition. Only few cases of facial talon cusps reported in the literature received complete treatment. Case reported by McNamara et al.[19] received extraction of permanent mandibular left central incisor, followed by orthodontic treatment. Another case reported by de Sousa et al.[22] was treated by root canal therapy and esthetic restoration for the permanent maxillary right central incisor. Two cases reported by Glavina et al.[28] received conservative management for facial talon cusp on permanent maxillary left central incisors, by gradual cuspal grinding and composite restorations. The case reported in this paper received successful conservative treatment for permanent maxillary left central incisor, maintaining the vitality of the dental pulp and was followed up for a period of 1 year.

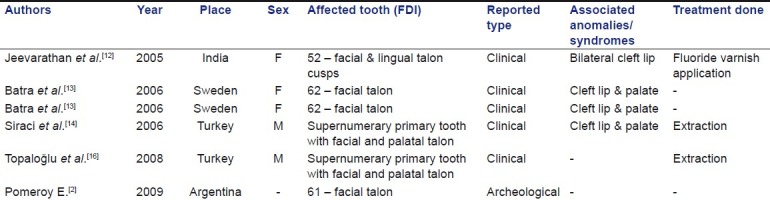

Table 1.

Reported cases of primary teeth with facial talon cusps seen in literature review

Table 2.

Reported cases of permanent teeth with facial talon cusps seen in literature review

A case reported by Abbott et al.[20] had a facial and palatal talon cusps on permanent maxillary left central incisor and was treated by cuspal reduction with endodontic treatment and orthodontic correction. Another case reported by Cubukcu et al.[29] had a geminated permanent maxillary right central incisor with facial and palatal talon cusp, which was extracted, followed by orthodontic correction and prosthetic rehabilitation. The junctional site of the talon cusp with the dental surface frequently allows plaque accumulation, leading to caries formation and pulpal inflammation or periodontal disease.[9] However, small cusps are asymptomatic and need no treatment, and large and prominent cusp as reported in the present case may result in compromised esthetics, soft tissue irritation and accidental cusp fracture, hence necessitating proper treatment.[9] In the present case, patient was willing for the treatment and wanted the affected tooth to appear like the adjacent unaffected one. The treatment plan was outlined in stages due to its severity, consisting of gradual reduction of the cusp in order to preserve the pulp vitality, as the vitality of the pulp-dentin complex plays an important role in the maintenance of a functional dentition.[33] The daily rate of reparative dentin formation after operative procedures varies with time. In humans, the average daily reparative dentin formation has been reported to be 2.8 μm for primary and 1.5 μm for permanent teeth.[34] The uniqueness about the present case is that, a large stage 3 talon cusp was managed conservatively by selective cuspal grinding and fluoride varnish application to reduce the dentinal sensitivity. The selective reduction of the talon cusp was carried out at an interval of 45 days each, over a period of 9 months. This allowed sufficient time for formation of the reparative dentin. Patient did not report sensitivity or any other pathology. Further, the case has been followed up successfully over a period of 1 year, without any post operative complications.

Conclusion

The present case report outlines the conservative management of stage 3 talon cusp. It is recommended to always begin with conservative treatment modality giving the tooth sufficient time to recover and respond by reparative dentin formation, so that pulp vitality can be maintained and invasive intervention can be avoided. Early diagnosis and treatment is recommended to avoid complications and to maintain healthy pulpal and periodontal status.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Bhussry BR, Sharawy Md. Development and growth of teeth. In: Bhaskar SN, editor. Orban's Oral histology and embryology. 11th ed. Missouri: Mosby (an imprint of Elsevier); 2004. pp. 28–48. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pomeroy E. Labial talon cusps: A South American archaeological case in the deciduous dentition and review of a rare trait. Br Dent J. 2009;206:277–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell WH. Case report. Dent Cosmos. 1892;34:1036. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulz C. Developmental abnormalities of the teeth and jaws. In: Gorlin RJ, Goldman HM, editors. Thoma's oral pathology. 6th ed. St Louis: MO: C. V. Mosby Co; 1970. pp. 96–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stojanowski CM, Johnson KM. Labial canine talon cusp from the Early Holocene site of Gobero, central Sahara Desert, Niger. Int J Osteoarchaeol. 2011;21:391–406. DOI:10.1002/oa.1144. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hattab FN, Yassin OM, Al-Nimrin KS. Talon cusp in permanent dentition associated with other dental anomalies: review of literature and report of seven cases. J Dent Child. 1996;63:368–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayes AT. Labial talon cusp: A case study of pre-European-contact American Indians. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:515–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tulunoglu Ö, Cankala D, Özdemir RC. Talon's cusp: Report of four unusual cases. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2007;25:52–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.31993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shashikiran ND, Babaji P, Reddy VV. Double facial and lingual trace talon csups: A case report. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2005;23:89–91. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.16449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sumer AP, Zengin AZ. An unusual presentation of talon cusp: a case report. Br Dent J. 2005;199:429–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Llena-Puy MC, Forner-Navarro L. An unusual morphological anomaly in an incisor crown. Anterior dens invaginatus. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2005;10:13–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeevarathan J, Deepti A, Muthu MS, Sivakumar N, Soujanya K. Labial and lingual talon cusps of a primary lateral incisor: A case report. Pediatr Dent. 2005;27:303–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Batra P, Enocson L, Hagberg C. Facial talon cusp in primary maxillary lateral incisor: A report of two unusual cases. Acta Odontol Scand. 2006;64:74–8. doi: 10.1080/00016350500443347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siraci E, Gungor H Cem, Taner B, Cehreli ZC. Buccal and palatal talon cusps with pulp extensions on a supernumerary primary tooth. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2006;35:469–72. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/64715224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsutsumi T, Oguchi H. Labial talon cusp in a child with incontinentia pigmenti achromians: Case report. Pediatr Dent. 1991;13:236–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Topaloğlu Ak A, Eden E, Ertuğrul F, Sütekin E. Supernumerary primary tooth with facial and palatal talon cusps: A case report. J Dent Child (Chic) 2008;75:309–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulze C. Anomalien und Mißbildungen der menschlichen Zähne. Berlin: Quintessenz Verlags-GmbH; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jowharji N, Noonan RG, Tylka JA. An unusual case of dental anomaly. A “facial” talon cusp. J Dent Child. 1992;59:156–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNamara T, Haeussler AM, Keane J. Facial talon cusp. Int J Pediatr Dent. 1997;7:259–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.1997.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abbott PV. Labial and palatal “talon cusps” on the same tooth: A case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85:726–30. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner CG. Another talon cusp: What does it mean? Dent Anthropol. 1998;12:10–2. [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Sousa SM, Tavano SM, Bramante CM. Unusual case of bilateral talon cusp associated with dens invaginatus. Int Endod J. 1999;32:494–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.1999.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mckaig SJ, Shaw L. Dens evaginatus on the labial surface of a central incisor; a case report. Dent Update. 2001;28:210–2. doi: 10.12968/denu.2001.28.4.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee C, Burnett SE, Turner CG. Examination of the rare labial talon cusp on human anterior teeth. Dent Anthropol. 2003;16:81–3. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patil R, Singh S, Reddy VV Subba. Labial Talon Cusp on Permanent Central Incisor: A Case Report. J Indian Soc Pedo Prev Dent. 2004;22:30–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunn WJ. Unusual case of labial and lingual talon cusps. Mil Med. 2004;169:108–10. doi: 10.7205/milmed.169.2.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oredugba FA. Mandibular facial talon cusp: case report. BMC Oral Health. 2005;5:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glavina D, Škrinjarić T. Labial talon cusp on maxillary central incisors: A rare developmental dental anomaly. Coll Anthropol. 2005;29:227–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cubukcu CE, Sonmez A, Gultekin V. Labial and palatal talon cusps on geminated tooth associated with dental root shape abnormality: A case report. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2006;31:21–4. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.31.1.a5101676k6714351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma MS. Facial talon cusp: A case report. Int Poster J Dent Oral Med. 2006;8:314. Poster. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ekambaram M, Yiu CK, King NM. An unusual case of double teeth with facial and lingual talon cusps. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:e63–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hegde KV, Poonacha KS, Sujan SG. Bilateral labial talon cusps on permanent maxillary central incisors: Report of a rare case. Acta Stomatol Croat. 2010;44:120–2. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nanci A. Tencate's Oral histology, development, structure and function. 6th ed. Canada: Mosby Publication; 2003. pp. 192–239. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seltzer S, Bender IB. In: Seltzer's The Dental Pulp, Biologic considerations in dental procedure. 3rd ed. First Indian ed. Chennai: All India Publishers and Distributors; 2000. Restorative and age changes of the dental pulp; pp. 324–48. [Google Scholar]