Abstract

Aim:

The aim of present study is to investigate the various psychological effects on children due to dental treatment.

Materials and Methods:

One hundred and eighty school going children, age range between six and twelve years, were recruited into the study and divided into two groups (Group I included six to nine-year-olds and Group II included nine-to-twelve year olds). Only those children were included who underwent a certain dental treatment seven days prior to the investigation. Each child was asked a preformed set of questions. The child was allowed to explain and answer in his own way, rather than only in yes or no. The answers were recorded. After interviewing, the child was asked either to draw a picture or to write an essay related to his experience regarding the dentist and dental treatment.

Results:

A majority of the children (92.22%) had a positive perception. The number of children having negative and neutral perceptions was comparatively much less. Younger children (Group I) had a more negative experience than the older children (Group II). Only one-fourth of the children complained of some pretreatment fear (23.83%); 72.09% of the children did not have any pain during dental treatment and a majority of children (80.23%) remembered their dental treatment.

Conclusion:

A majority of children had a positive perception of their dental treatment and the children in the younger age group had more negative perceptions than the children in the older age group.

Keywords: Children, dental treatment, perception, psychological effects

Introduction

In dental practice, it is experienced that most of the children do not cooperate during dental procedures. Sometimes it becomes very difficult to manage a child in a dental clinic. These difficulties of management are not only related to the technical procedures of treatment, but also with the different emotional upsets of the child. The most common emotional upsets exhibited during dental treatment are anxiety and fear, which may originate from a previous traumatic experience in the dental office or during hospitalization for other purposes.[1]

In this view, the present study was aimed at investigating the psychological effects on children (age range-six to twelve years) after dental treatment, through a questionnaire, drawings, and essays.

Materials and Methods

One hundred and eighty school going children (age range — six to twelve years) were selected from the Department of Pedodontics and Preventive Dentistry, NIMS Dental College, Jaipur. The entire sample was divided equally into two groups: Group I included ninety children between six and nine years of age and Group II included ninety children between nine and twelve years of age. There was no discrimination with respect to their sex or socioeconomic status. Only those children who underwent a certain dental treatment seven days prior to investigation were included in the study. The time for investigation was ascertained to be between eight and fourteen days after the dental treatment. This was done to obtain stable impressions about the dental treatment, from the children.

The following criteria were used for selecting children, to avoid inherent personal error during investigation:

Children treated by the investigator were discarded from the study

The personality and nature of the dentist who treated the child was not known to the present investigator

The behavior of the child during the entire treatment was also unknown to the investigator

The type of treatment received by the child was also unknown to the investigator

To assess the psychological effects of dental treatment, each child was interviewed by the investigator in a separate room, where only the child and investigator were present. Sufficient time was allowed to develop a rapport with the child. During the interview, a child who clinically appeared to be less than average for his level of intelligence, was subjected to the Stanford- Binet Intelligence Test.[2] Only one child was found to have subnormal I.Q. (less than 80).

The identification data, education, income of the parents, and address were noted on a proforma. A note was made of the general appearance and behavior of the child during the interview; specially his mood, level of cooperation, attention, speech, and language. Each child was then asked to answer a preformed set of questions (adopted from the study by Klein, 1967).[3] The questions were as follows:

Have you visited a dentist?

Why did you visit a dentist?

Could you tell me something about the dentist and draw me a picture or write an essay?

Were you afraid to go to the dentist?

Do you remember the treatment you received?

Did it hurt?

Do you like the dentist?

The child was allowed to explain and answer in his own way and time, rather than only in ‘yes’ or ‘no’. The answers were recorded.

After the interview, the child was asked either to draw a picture or to write an essay related to his experience with the dentist and the dental treatment. Children falling in Group I were asked to draw a picture on a drawing sheet, related to their dental experience, as it was thought that they might not be able to write down their feelings very well, and they were asked to describe it.

In Group II, the children were asked to write an essay on a topic, ‘A visit to the dentist’. The child was given an option to write either in English or in Hindi.

Observations and Results

The dental treatment perceptions were rated positive, neutral or negative, on the basis of questions 3, 6, and 7 in all children (because these questions were considered to be most important in the evaluation of the child's perception about the dental treatment. The rest of the questions were considered to be supportive in nature) and the drawings and essays in group I and II, respectively.

Ratings of questions 3, 6, and 7

Question No. 3: Could you tell me something about the dentist and draw me a picture or write an essay?

Positive: The dentist and / or the dental situation liked by the subject. When other characteristics of the dentist, such as kind, nice, gentle, handsome, were also described, the categorization was further supported

Neutral: No opinion was given for good or bad

Negative: The situation or the dentist described as definitely bad

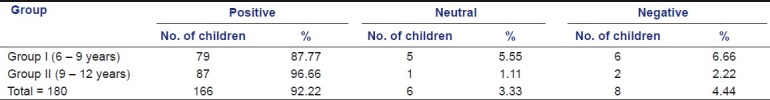

Majority of the children (92.22%) had a positive perception. Younger children (Group I) had a more negative experience than the older children (Group II) (6.66 and 2.22%), respectively. [Table 1]

Table 1.

Subject's perception of the dental treatment

For the purpose of clarity, the data of the positive and neutral groups were pooled because the number of subjects in the neutral group was very small (six). Thus, the total number of subjects in the combined positive and neutral groups becomes 172.

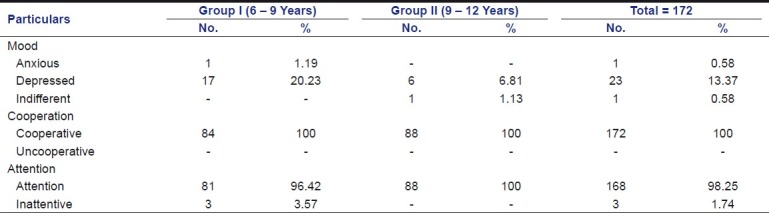

Table 2 shows that disturbances in mood had been relatively more common in the younger group than in the older group. Depression was the predominant disturbance. Anxiety and indifferent mood were seen only in one child each. All children were cooperative. Only few children (1.7%) showed inattention and belonged to the younger age group.

Table 2.

Mood, level of cooperation, and attention of the children in relation to their perceptions (Combined group)

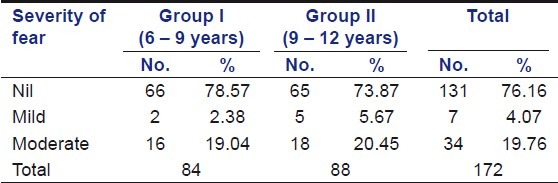

A large number of children had no pretreatment fear (76.16%). Approximately one-fourth of the children complained of some pretreatment fear (23.83%). Of which, 19.76% had moderate fear.

Question No. 6: Did it hurt?

Positive and neutral: Little or no pain

Negative: Complained of marked pain

In the combined group 72.09% of the children did not have any pain during dental treatment, and 27.90% complained of mild-to-moderate pain. There was no significant difference between the two groups. [Table 3].

Table 3.

Pretreatment fear in the combined group

A majority of children remembered their dental treatments (80.23%), which were restoration of teeth including pulp therapy and crowns, extractions, and space maintainers. The younger group children were more apt to forget their treatment than those in the older group. All the children in the negative group remembered their dental treatment, which was extraction in each case.

Question No. 7: Do you like the dentist?

Positive: A definite yes

Neutral: No answer given / No opinion

Negative: A definite No, or the dentist described as bad

Ratings of drawings

Positive

Relevant to the dental treatment situation or the dentist or self

Emotions of the subject and / or of others shown, as of happiness

A number of items of the treatment situation are depicted in bright colors

Neutral

Irrelevant

No definite emotion of either happiness or sadness shown

Only few items of the dental situation

Negative

Definite emotion of unhappiness of the subject

A potentially painful or fearful item like syringe and needle shown

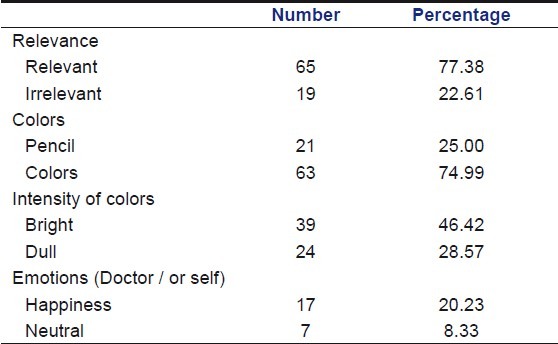

A large number of children made relevant and colorful drawings (77.38%). Nearly half of the children used bright colors; 28.57% drew the dentist and themselves in their pictures; and 20.23% showed a definite emotion of happiness.

Irrelevant themes were very diverse and ranged from house (neither of doctor nor of self, seven subjects) to pilot and church (one each). Other things (22.67%) were fruits, flowers, ducks, birds, television, airplane, almirah, joker, calendar, dustbin, fan, ball, boy, umbrella, clouds, well, and a design of a saree border.

Among other important theme in the drawings was equipment. The most common items were mouth-mirror, probe, and dental chair (19, 9, 8 subjects, respectively). Next in order were light, bucket, chip blower, dental unit, and instrument tray. Forceps, toothbrush, toothpaste, impression tray, and injection ampules, were the other things shown. Four children depicted teeth in their drawings.

Most of the children (five) in the negative group drew relevant pictures. A pencil was preferred over colors. Three children depicted themselves and one child depicted both the dentist and self. All children showed themselves as unhappy or crying. One child, who drew the dentist, had shown him to be big and smiling and himself diminutive and crying.

Ratings of essays

Positive

Treatment situation and / or dentist described as good

Relief from ailment or any other benefit indicated

Hospital building and personnel described as good

Ambition of becoming a dentist expressed

Neutral

No opinion regarding the dentist or the treatment situation

Negative

Dentist and other situations described as definitely bad

Too much pain

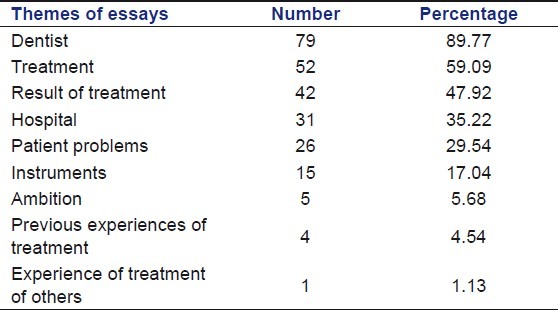

Dentists figured very prominently in the essay themes (89.77%). Treatment procedures and their results were the next common contents (59.09 and 47.72%, respectively). Nearly one-third of the children described the hospital (35.22%). This was closely followed by their own problems (29.54%); 17.04% were also able to add instruments in their essays. Five children expressed their ambition of becoming dentists.

The overall rating of the perception of a dental treatment situation was given on the basis of the following criteria.

Question Nos. 3 and 7 were considered more important in the perception categorization. For example, if a child was rated positive on one or both of these questions and his drawings or essays were neutral, the total perception was rated as positive.

If, in the above circumstances, either question No.3 and / or 7 were rated negative, then the overall perception was rated as negative.

If question Nos. 3 and 7 were rated neutral and drawings or essays were rated either as positive or negative, the overall perception was rated as positive or negative, respectively.

If a rating of positive or negative in any one of the questions 3 or 7, drawing or essay were positive or negative, while the rest were neutral, the overall perception was rated as positive or negative, respectively.

Question No.6 was only a supportive criterion.

Discussion

The current, existing measures of dental fear are numerous. Past classifications were based on the type of tools, such as, psychometric scales, behavioral rating scales, physiological and hormonal measures, and projection techniques.[4]

Several investigations have measured children's physiological reactions to dental settings and used heart rate, pulse rate, skin conductance, muscle tension, blood pressure, palmer sweating, and decreased salivary secretion, as indirect measures of dental fear.[5] This in itself could affect the results, because the equipment could provoke anxiety.[6] The measurement of free cortisol in saliva has been found to be a reliable method of measuring stress and fear in children.[7]

Psychometric questionnaires directly measuring dental fear and designed to be filled out by patients, helped to overcome some of the problems identified with the tools discussed herein, and were used in present study.

The first finding to emerge from the present study was that out of a total of 180 children, a majority had a positive perception of the dental treatment situation [92.2%, Table 1]. Only 3.33 and 4.44% had a neutral and negative perception, respectively [Table 1], indicating that dental treatment did not always present a psychologically traumatic experience. This finding was in accordance with the findings of Croxton[8] and Rosenzweig and Addelston.[9] Oppenheim and Frankl also found that 82% of the 95 children were good patients.[10] In contrast, Klein reported a much higher percentage for negative experience (52.23%) in his study of 111 children, with age between three and six years.[3]

The younger group of children had a more negative perception than the older age group of children [6.6 and 2.2%, respectively, Table 1], which could be because of the fact that younger children could not comply satisfactorily. A similar finding was reported by Ober-Bell,[11] Klein,[3] and Oppenheim and Frankl.[10]

Klein[3] found unusual behavior or emotional changes only in children having a negative experience. In our sample, disturbances of mood were found even in children having a positive and neutral experience. Depression was the most common disturbance of mood [13.37%, Table 2] and this could not be explained in terms of perceptions in this group. In both the combined and the negative perception groups, the younger group of children had more disturbances than the older group.

All children in our sample were found to be cooperative, irrespective of their perceptions of the dental treatment [Table 2]. Inattention was rare in the combined group [1.74%, Table 2]. Children with negative perception were more inattentive. In both the combined and negative perception groups, the younger group children were more inattentive. These findings were understandable in terms of the children's perception and their relative level of maturity.

Although fear in connection with dental treatment has been described by a number of workers (Ober-Bell,[11] Coriat,[12] Fisher,[13] Teuscher,[14] Rosengarten,[15] 1961; Finn[16]), very few of them have specified pretreatment fear, which is an important factor affecting the perception of the child. In the present study, in the combined group, a large number (76.16%) of children had no pretreatment fear [Table 3]. Approximately one-fourth of the children (23.8%) had mild-to-moderate fear. In the negative perception group, all the children, except one, had pretreatment fear of moderate intensity.

Pain is an important consideration, while considering the psychological effects of dental treatment. Pain during dental treatment is supposed to be due to the emergence of repressed hostility of the patient toward the dentist (Lefer).[17] It follows that those who experience greater pain during their dental treatment also have a negative perception of it. In the negative perception group all children, excepting one, had experienced pain. In the combined group, 72.09% of the children did not complain of any pain; 27.90% children in this group did complain of mild-to-moderate pain, and yet their perception of the treatment situation was predominantly positive. This suggested that pain was perhaps not an essential criterion for negative perception, as one would think, seeing the pain experienced by the children of the negative group [Table 4].

Table 4.

Pain experienced during dental treatment in the combined group

A majority of children remembered their dental treatment (80.23%). Children in the younger group were more apt to forget their treatment than those in the older group. All children in the younger group with negative perception remembered their treatment, which was extraction in each case.

Projection techniques are of special interest, as they suggest a way of revealing unconscious or hidden emotions. They enable information to be obtained about a child's feelings and thoughts about dental care, which may be difficult to obtain through other methods. The technique includes, for example, the child's interpretation of picture stories, the child's drawing of a person or the child being asked to tell a story about something or someone. These measures are used commonly in clinical child psychology. The frequent form of use of this technique has been letting a child draw a picture.[5]

Klein[3] contended that a child who had a negative experience will draw pictures that are not relevant to the dental treatment situation. In his study, 30% of the nursery school children made fearful animals, which were symbolic of fearful dental treatment / dentist. In contrast, in the present study all children in the negative perception group, except one, drew relevant pictures. The themes in their pictures were injection syringe and needle, a potentially painful and fearful object, and drawings of self and dentist (needle phobia in children is described by Ayer[18]). All children depicted themselves as unhappy or crying and they preferred pencil over colors. However, in the combined group, 77.38% drew relevant pictures, while 22.61% drew irrelevant ones [Table 5]. The themes were very diverse and included fruits, flowers, a duck, a bird, television, airplane, almirah, joker, dustbin, pilot, church, a well, and a pattern of a saree border. It could be because these pictures were easy to draw or were the things they could draw the best. They preferred bright colors.

Table 5.

Analysis of the drawings of the combined group

As expected, in the combined and negative perception groups, the children in the older group could describe their feelings fairly well. In the combined group, the dentist figured prominently [89.77%, Table 6] in the essay themes. Treatment procedures and their results, hospitals, and instruments were the other themes. Five children expressed their ambition to become dentists. In the negative perception group, the essays (two subjects) were brief.

Table 6.

Themes in the essays of the combined group

Although from the results of this study, the negative perception group and the combined group are not mutually comparable, a child who has negative perceptions about a dental treatment is more likely to be a young child, a child with moderate pretreatment fear and pain during dental treatment[19] or a child who has a mood disturbance and perhaps inattention at the time of investigation. In the present study, negative perceptions were found to be less, perhaps because we are culturally more accepting. Anything disagreeable or unpleasant done by or linked with authority figures, like a doctor, is less likely to be perceived and expressed as negative.

A majority of the children had a positive perception of the dental treatment situation. This could be due to the effect of age (six-to-twelve years).[20] Ober-Bell observed that with increasing maturity, a positive perception of the dental treatment situation increases.[11]

Conclusion

The following conclusions were drawn from the present study:

A majority of the children had a positive perception of their dental treatment

Only few children had neutral and negative perceptions, in both age groups

The children from the younger age group had more negative perceptions than the children from the older age group

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Brill WA. The effect of restorative treatment on children's behavior at the first recall visit in a private pediatric dental practice. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2002;26:389–94. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.26.4.r1543673rx055355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terman LM, Merrill MA. Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale: Manual for the Third Revision Form L-M, London-Toronto-Willington. Sydney: George G. Harrap and Co. Ltd; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein H. Psychological effects of dental treatment on children of different ages. J. Dent Child. 1967;34:30–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Folayan MO, Kolawole KA. A clinical appraisal of the use of tools for assessing dental fear in children. Afr J Oral Health. 2004;1:54–63. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irwan M, Hauger RL. Development aspects of psychoneuroimmunology in child and adolescent psychiatry. In: Lewis M, editor. A comprehensive textbook. Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins; 1991. pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klingberg G. Dental fear and behavior management problems in children. Swed Dent J Suppl. 1995;103:71–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell JR, Martino G, Meredith KE, Schwartz GT, Siani MM, Morrow FD. Vascular diseases risk factors, urinary free cortisol and health histories in older adults. Biol Psychol. 1993;35:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(93)90090-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Croxton WL. Child behavior and the dental experience. J Dent Child. 1967;34:212–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenzweig S, Addelston HK. Children's attitude towards dentists and dentistry. J Dent Child. 1968;35:129–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oppenheim MN, Frankl SN. A behavioral analysis of the preschool child when introduced to dentistry by the dentist or hygienist. J Dent Child. 1971;38:317–325. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ober-Bell J. Psychological aspects of dental treatment of children, Madison. Experiment. Educ J. 1943;13:71–86. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coriat SH. Dental anxiety: Fear of going to the dentist. Psychoan Rev. 1946;33:365–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher CG. Theoretical aspect of fear. J Dent Child. 1951;22:38–40. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teuscher GW. The application of psychology in Pedodontics. Dent Clin North Am. 1961;6:533–538. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosengarten M. Behavior of the preschool child at the initial dental visit. J Dent Res. 1961;41:673–4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finn SB. Clinical Pedodontics. 4th ed. Philadelphia, London and Toronto: W.B. Saunders Co; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefer L. Psychiatry and Dentistry. In: Freedman AM, Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, editors. In comprehensive Text Book of Psychiatry. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. Baltimore: The Williams and Wilkins Co; 1975. pp. 1765–1773. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ayer WA. Use of visual imagery in needle phobic children. J Dent Child. 1973;40:41–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arnup K, Broberg AG, Berggren U, Bodin L. Treatment out-come in subgroups of uncooperative child patients: An exploratory study. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2003;13:304–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2003.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baier K, Milgrom P, Russell S, Mancl L, Yoshida T. Children's fear and behavior in private pediatric dentistry practices. Pediatr Dent. 2004;26:316–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]