Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Patient satisfaction is increasingly regarded as an important aspect of measuring treatment success in individuals with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

OBJECTIVE:

To review how satisfied patients with GERD are with their medication, and to analyze the usefulness of patient satisfaction as a clinical end point by comparing it with symptom improvement.

METHODS:

Systematic searches of the PubMed and EMBASE databases identified clinical trials and patient surveys published between 1966 and 2009.

RESULTS:

Twelve trials reported that 56% to 100% of patients were ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with proton pump inhibitor (PPI) treatment for GERD. Patient satisfaction levels were higher for PPIs than other GERD medications in two trials. The sample-size-weighted average proportion of patients ‘satisfied’ with their PPI after four weeks of treatment in trials was 93% (95% CI 87% to 99%), with 73% (95% CI 62% to 83%) being ‘very satisfied’. In four surveys, the average proportion of patients ‘satisfied’ with their PPI treatment was 82% (95% CI 73% to 90%) and 62% (95% CI 48% to 75%) were ‘very satisfied’. Seven trials found a positive association between patient satisfaction and symptom improvement, and two surveys between satisfaction and improved health-related quality of life. Three trials found that continuous treatment yielded higher rates of satisfaction than on-demand therapy.

CONCLUSIONS:

More than one-half of patients were satisfied with their PPI medication in trials, and more patients were satisfied with PPIs than other medication types. An association between patient satisfaction and symptom resolution was found, suggesting that patient satisfaction is a useful end point for evaluating GERD treatment success.

Keywords: GERD, Medication, Patient-reported outcome, Satisfaction, Therapy

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

La satisfaction des patients est de plus en plus perçue comme un aspect de la mesure de réussite du traitement chez les personnes ayant un reflux gastro-œsophagien (RGO).

OBJECTIF :

Analyser la satisfaction des patients ayant un RGO envers leur médicament ainsi que l’utilité de la satisfaction des patients à titre de paramètre clinique par rapport à la diminution des symptômes.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Grâce à des recherches systématiques dans les bases de données PubMedet EMBASE, les chercheurs ont repéré des essais cliniques et des enquêtes auprès de patients, publiés entre 1966 et 2009.

RÉSULTATS :

Douze essais ont indiqué que de 56 % à 100 % des patients étaient « satisfaits » ou « très satisfaits » du traitement du RGO à l’aide d’inhibiteurs de la pompe à protons (IPP). Dans deux essais, les taux de satisfaction étaient plus élevés envers les IPP qu’envers les autres médicaments contre le RGO. La moyenne des patients « satisfaits » de leur IPP après quatre semaine de traitement dans le cadre des essais, redressée selon la dimension de l’échantillon, s’élevait à 93 % (95 % IC 87 % à 99 %), 73 % (95 % IC 62 % à 83 %) étant « très satisfaits ». Dans quatre enquêtes, la proportion moyenne de patients « satisfaits » par leur traitement aux IPP correspondait à 82 % (95 % IC 73 % à 90 %), tandis que 62 % (95 % IC 48 % à 75 %) étaient « très satisfaits ». Sept essais ont établi une association positive entre la satisfaction des patients et la diminution des symptômes, et deux essais, entre la satisfaction et une amélioration de la qualité de vie liée à la santé. Trois essais ont établi qu’un traitement continu suscitait de plus forts taux de satisfaction qu’un traitement sur demande.

CONCLUSIONS:

Plus de la moitié des patients étaient satisfaits de leur médicament par IPP lors des essais, et plus de patients étaient satisfaits des IPP que des autres types de traitement. L’association avec la satisfaction des patients est un paramètre utile pour évaluer le succès du traitement du RGO.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), characterized by troublesome heartburn and/or acid regurgitation (1), is a chronic disease that has a substantial impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (2,3). The patient’s perspective on treatment outcome is increasingly being regarded as an important aspect of measuring the success of treatment for GERD in both clinical practice and research (4).

At an international workshop on symptom evaluation in reflux disease, 93% (26 of 28) of participants agreed on the need for increased emphasis on patient satisfaction as an outcome in treatment trials (5). Furthermore, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently issued guidelines supporting the use of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials (6). It is likely that the FDA guidance will translate into policy in the near future, although there is agreement that HRQoL and patient satisfaction should not be a primary outcome measure in clinical trials (7).

Although an increasing number of studies are measuring patient satisfaction with GERD treatment, there has been no systematic review of the evidence to determine whether patient satisfaction is of use as an outcome measure and in differentiating treatments. The aims of the present systematic review were first to assess how satisfied GERD patients are with their medications and, second, to analyze the value of patient satisfaction as an end point, by comparing it with another measure of treatment success, symptom improvement.

METHODS

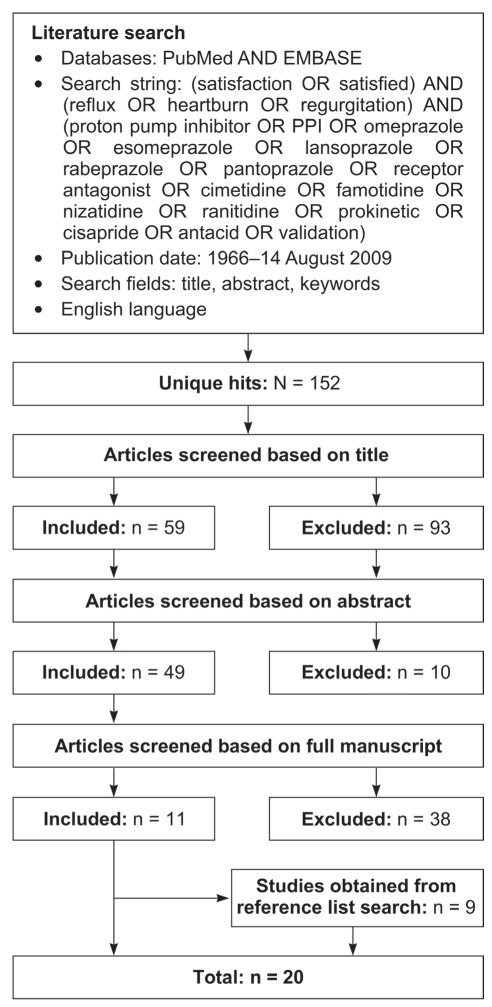

PubMed and EMBASE were systematically searched to identify articles published in English between January 1966 and August 14, 2009, using the search strategy detailed in Figure 1. As additional sources of data, the reference lists of selected review articles were also searched.

Figure 1).

Literature search strategy

Study selection

Data were obtained from clinical trials (randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and open-label studies, including those using on-demand treatments) in which patient-reported satisfaction was an outcome. Population-based surveys that included assessment of the proportion of individuals with GERD who were satisfied with their treatment were also selected. The medications searched for included proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), histamine type 2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs), antacids and prokinetics (Figure 1).

Ten clinical trials were excluded for the following reasons: five because the percentage of patients satisfied with treatment or a mean satisfaction score from a questionnaire were not reported; two trials because therapy was used in conjunction with surgery; one trial because satisfaction was not patient-reported; one trial because the data were reported only in the congress abstract and not in the full article; and one trial because the study focused on satisfaction after switching medication. Four patient surveys were excluded because the percentage of patients satisfied with treatment were not reported; one survey was excluded because it focused mainly on switching medication.

The following data were collected from the full-text articles describing the selected studies: study design, participant details (including whether endoscopy had been performed), sample size, details of medication, definition of satisfaction, satisfaction rating scale, and the proportion of satisfied patients or mean satisfaction score.

Definition of satisfaction

Two levels of satisfaction were assessed. Patients were considered to be very satisfied if they reported being ‘extremely satisfied’, ‘totally satisfied’, ‘completely satisfied’, ‘very satisfied’, ‘good’, ‘very good’ or ‘excellent’. Patients were considered to be satisfied if they had reported being ‘very satisfied’ (thus ‘satisfied’ incorporates ‘very satisfied’), ‘satisfied’, ‘quite satisfied’, ‘moderately satisfied’, ‘slightly satisfied’ or ‘somewhat satisfied’, or gave a ‘positive response’ or ‘yes’ when asked if they were satisfied.

Analysis

Data from five, double-blind RCTs and three open-label trials that reported satisfaction after four weeks of treatment were pooled to calculate the average proportion of patients who were satisfied (weighted according to sample size) with different PPIs. Satisfaction with continuous PPI therapy was compared with satisfaction with on-demand PPI therapy. When trials also involved treatment with an H2RA, this was also analyzed, as were satisfaction scores according to the presence of reflux esophagitis. The relationships between patient satisfaction, reflux symptom relief (improvement) and resolution (complete absence of symptoms), and changes in HRQoL were examined. In addition, data from each of the surveys that met the inclusion criteria were also compared, and the data from four surveys were pooled to calculate the average proportion of patients satisfied with PPI treatment.

RESULTS

Overall, the searches identified 152 articles published between January 1966 and August 2009 (Figure 1). After screening the title, abstract or full text, 11 relevant articles remained, and an additional nine studies were obtained from citation lists. Thus, a total of 20 articles that reported patient satisfaction with GERD medication were included in the present review.

Patient satisfaction with treatment

Clinical trials:

Satisfaction with treatment was an end point in 14 clinical trials involving patients with GERD. Of these, 12 articles reported the proportion of patients who were ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with treatment (Table 1). One-half of the studies (8–13) started with PPI treatment given on an open-label basis, followed by randomization to on-demand or continuous treatment for patients who had achieved symptom control (defined as the complete absence of symptoms in the previous seven days or mild symptoms on a maximum of one day in the previous seven days) in the open-label arm of the study. One study followed the open-label arm with randomization to on-demand or intermittent treatment (14). One study began with a four-week or eight-week RCT, before progressing to an open-label regimen (15); three studies were only RCTs (16–18); and one trial was exclusively open label (19). Two studies reported head-to-head comparisons of satisfaction with different PPIs (ie, studies that used different PPIs in a single, randomized, parallel-group trial) (9,15).

TABLE 1.

Articles reporting treatment satisfaction as an outcome in clinical trials of medications for GERD

| Author (ref) | Study design | Baseline symptoms | RE | Treatment | Length of treatment | Scale |

Defined as |

Satisfied*,% | Very satisfied, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Satisfied’ | ‘Very satisfied’ | |||||||||

| Bate et al (17) | Randomized, double-blind | Heartburn predominant symptom ≥2 days/week | Present (up to grade 3)† or absent | Omeprazole 20 mg once daily (n=112) | 4 weeks | 6-point scale | 1–3 | 1–2 | 94 | 56 |

| Cimetidine 400 mg 4 times per day (n=109) | 4 weeks | 79 | 33 | |||||||

| Lind et al (16) | Randomized, double-blind | Heartburn predominant symptom ≥2 days/week | Absent | Omeprazole 20 mg once daily (n=205) | 4 weeks | Response | Responded as satisfied | – | 66 | – |

| Omeprazole 10 mg once daily (n=199) | 4 weeks | 57 | – | |||||||

| Placebo (n=105) | 4 weeks | 31 | – | |||||||

| Mulder et al (15) | Part 1: Randomized, double-blind |

Symptomatic | Present (grade 1–4)‡ | Omeprazole 20 mg once daily (n=151) | 4 weeks | Positive response | Positive answer | – | 79 | – |

| 8 weeks | 89 | |||||||||

| Lansoprazole 30 mg once daily (n=154) | 4 weeks | 76 | – | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 86 | – | ||||||||

| Pantoprazole 40 mg once daily (n=156) | 4 weeks | 79 | – | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 91 | |||||||||

| Part 2: Open-label |

Patients satisfied from part 1 after 4 or 8 weeks | Omeprazole 20 mg once daily (n=370) | 3 months | 87 | – | |||||

| Patients satisfied from part 1 after 12 weeks | Omeprazole 40 mg once daily (n=21) | 3 months | 81 | – | ||||||

| Engels et al (8) | Part 1: Open-label |

Moderate heartburn ≥3 days/week | Present (LA grade A or B) or absent | Esomeprazole 40 mg once daily (n=1170) | 2 weeks | Not specified | Responded as satisfied | – | 90 | – |

| 4 weeks | 92 | – | ||||||||

| 8 weeks | 93 | – | ||||||||

| Part 2: Randomized, single-blind |

Patients relieved of symptoms in part 1 | Esomeprazole 20 mg once daily continuously (n=528) | 3 months | 90 | – | |||||

| Esomeprazole 40 mg on-demand (n=524) | 3 months | 88 | – | |||||||

| Tsai et al (9) | Part 1: Open-label |

Heartburn predominant symptom ≥ 4 days/week | Absent | Esomeprazole 20 mg once daily (n=774) | 2 weeks | 7-point scale | 1–4 | 1–2 | – | – |

| 4 weeks | ||||||||||

| Part 2: Randomized, single-blind |

Patients relieved of symptoms in part 1 | Esomeprazole 20 mg on-demand (n=311) | 4 weeks | 93 | – | |||||

| 3 months | 93 | |||||||||

| 6 months | 92 | |||||||||

| Lansoprazole 15 mg once daily (n=311) | 4 weeks | 88 | – | |||||||

| 3 months | 88 | |||||||||

| 6 months | 89 | |||||||||

| Meineche-Schmidt et al (14) | Part 1: Open-label |

Heartburn predominant symptom (with or without acid regurgitation) ≥3 days/week | Not specified | Esomeprazole 40 mg once daily (n=1583) | 4 weeks | 7-point scale | 1–4 | 1–2 | – | – |

| Part 2: Randomized | Patients relieved of symptoms in part 1 | Esomeprazole 20 mg on-demand (n=453) | 6 months | 96 | 80 | |||||

| Esomeprazole 40 mg intermittent 2 weeks (n=449) | 6 months | 96 | 74 | |||||||

| Esomeprazole 40 mg intermittent 4 weeks (n=445) | 6 months | 97 | 84 | |||||||

| Pace et al (10) | Part 1: Open-label |

Symptoms of GERD | Absent or mild | Esomeprazole 40 mg once daily (n=5502) | 4 weeks | 7-point scale | 1–4 | 1–2 | 96 | 64 |

| Part 2: Randomized, double-blind |

Patients with mild symptoms or relieved of symptoms in part 1 | Esomeprazole 20 mg continuously (n=2628) | 6 months | – | 65 | |||||

| Esomeprazole 20 mg on-demand (n=2637) | 6 months | – | 60 | |||||||

| Degl’ Innocenti et al (19) | Open-label | Diagnosed moderate-to-severe GERD, symptomatic ≥3 months | Present or absent | Esomeprazole 40 mg once daily (n=217) | 4 weeks | 7-point scale | 1–3 | 1–2 | 90 | 75 |

| Cibor et al (13) | Part 1: Open-label |

Mild reflux symptoms ≥3 months | Absent | Lansoprazole 30 mg daily (n=65) | 4 weeks | 4-point scale | – | 0 | – | – |

| Part 2: Randomized |

Patients relieved of symptoms in part 1 | Lansoprazole 30 mg on-demand (n=20) | 3 months | – | 90 | |||||

| 6 months | 90 | |||||||||

| 12 months | 90 | |||||||||

| Lansoprazole 15 mg once daily (n=20) | 3 months | – | 100 | |||||||

| 6 months | 95 | |||||||||

| 12 months | 95 | |||||||||

| Lansoprazole 30 mg in 4-week courses during a relapse (n=20) | 3 months | – | 90 | |||||||

| 6 months | 85 | |||||||||

| 12 months | 85 | |||||||||

| Hansen et al (12) | Part 1: Open-label |

Heartburn predominant symptom (with or without acid regurgitation) ≥3 days/week | Present or absent | Esomeprazole 40 mg once daily (n=1902) | 4 weeks | 7-point scale | 1–4 | 1–2 | – | 93 |

| Part 2: Randomized |

Patients relieved of symptoms in part 1 | Esomeprazole 20 mg once daily continuously (n=658) | 6 months | – | 82 | |||||

| Esomeprazole 20 mg on-demand (n=634) | 6 months | 75 | ||||||||

| Ranitidine 150 mg twice daily continuously (n=610) | 6 months | – – |

34 | |||||||

| Beyer-dorffer et al (11) | Part 1: Open-label |

Heartburn predominant symptom for >6 months and ≥4 days/week | Absent | Esomeprazole 20 mg once daily (n=877) | 4 weeks | 5-point scale | 1–3 | – | – | – |

| Part 2: Randomized, open-label |

Patients relieved of symptoms in part 1 | Esomeprazole 20 mg once daily continuously (n=297) | 6 months | 86 | – | |||||

| Esomeprazole 20 mg on-demand (n=301) | 6 months | 82 | – | |||||||

| Eggleston et al (18) | Randomized, double-blind | Symptoms of GERD | Not specified | Rabeprazole 20 mg once daily (n=1392) | 4 weeks | 5-point scale | 1–2§ | 1–2§ | – | 78 |

| Esomeprazole 40 mg once daily | 4 weeks | – | 82 | |||||||

| Esomeprazole 20 mg once daily | 4 weeks | – | 78 | |||||||

Includes patients who were very or completely satisfied;

Grade 0 = Normal, 1 = No macroscopic erosions, 2 = Isolated erosions, 3 = Confluent erosions, 4 = Frank benign ulcer (unspecified classification system);

Modified Savary-Miller classification: grade 1 = Linear erosions; 2 = Confluent erosions; 3 = Longitudinal, confluent or circumferential erosions that bleed easily; 4a = Ulceration(s) in mucosal transition zone, 4b = With the presence of stricture but without erosions or ulcerations;

Study reports satisfaction as combined ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’. GERD Gastroesophageal reflux disease; LA Los Angeles; RE Reflux esophagitis; ref Reference

Patient satisfaction scales had between four and seven ordered response categories, except for three studies (8,15,16) that used a ‘positive response’ or a ‘yes’ answer to record patient satisfaction. An additional two studies described the degree of satisfaction in terms of mean scores obtained from a questionnaire (20,21).

All 12 articles that reported the proportion of patients satisfied with treatment assessed satisfaction with PPI therapy. Collectively, 57% to 97% of patients were ‘satisfied’, and 56% to 100% were ‘very satisfied’. In the only two articles reporting satisfaction with H2RA treatment (12,17), 79% of patients were ‘satisfied’, but only 33% to 34% were ‘very satisfied’.

Three studies reported head-to-head comparisons of satisfaction with different PPIs. In the acute phase of the trial reported by Tsai et al (9) patients received esomeprazole 20 mg once daily for two or four weeks. Asymptomatic patients then entered the maintenance phase comparing esomeprazole 20 mg on-demand (n=311) with lansoprazole 15 mg continuous daily treatment (n=311) for six months. After one month, significantly more patients were satisfied with esomeprazole on-demand treatment than continuous lansoprazole treatment (93% versus 88% [P=0.02]). Although the numerical difference of 5% in the proportion of satisfied patients between the two regimens was small, it was statistically significant and translated into a difference between the two PPIs in the time to discontinuation from the maintenance phase because of unwillingness to continue. By six months, significantly more patients were unwilling to continue with continuous lansoprazole treatment than with esomeprazole on-demand treatment (13% versus 6% [P=0.001]) (9).

The second study also had two parts: the first compared treatment with continuous omeprazole 20 mg, lansoprazole 30 mg and pantoprazole 40 mg. Patient satisfaction at four weeks was 79% for omeprazole and pantoprazole, and was 76% in the lansoprazole group (no statistically significant differences among the treatment groups) (15).

In the third trial (18), patient satisfaction at four weeks with rabeprazole and esomeprazole (both 20 mg once daily) was 78%. Although satisfaction with esomeprazole 40 mg once daily was numerically higher (82%), the difference was not significant (P=0.209).

In the pooled analysis of trials reporting satisfaction after four weeks, the average proportion of patients satisfied with their PPI treatment, weighted according to sample size, was 93% (95% CI 87% to 99%). Overall, 73% (95% CI 62% to 83%) of patients were ‘very satisfied’. The average level of satisfaction from three trials with omeprazole 20 mg once daily was 77% (95% CI 61% to 93%) (15–17); from two trials with lansoprazole at 15 mg once daily (9) and 30 mg once daily (15) was 84% (95% CI 72% to 95%); from one trial with pantoprazole 40 mg once daily was 79% (15); and from four trials with esomeprazole was 95% (95% CI 92% to 98%) (8–10,19). However, the studies had varied designs, and only the trial by Mulder et al (15) reported any head-to-head comparisons of the different PPIs; therefore, it was not possible to determine from the pooled data whether there were clinically important differences among the PPIs for the satisfaction end point.

The proportion of patients with reflux esophagitis varied among studies and, in three trials, none of the participants underwent endoscopy (Table 1) (12,14,19). It was not possible to correlate levels of satisfaction with healing of reflux esophagitis because the studies did not provide satisfaction values stratified according to these individual subgroups.

In one study, patient satisfaction with treatment effectiveness was the primary outcome of the maintenance phase (8). Patients with and without reflux esophagitis were treated with continuous esomeprazole 40 mg once daily for two, four or eight weeks. Following this, patients were randomly assigned to esomeprazole 40 mg once daily on-demand or continuous esomeprazole 20 mg once daily for three months. The proportion of patients satisfied with maintenance treatment was similar between patients with reflux esophagitis and those without (88% versus 90%) (8).

Three of the four studies that directly compared long-term (three to six months) continuous treatment with on-demand therapy found that continuous treatment yielded significantly higher rates of satisfaction (Table 1) (8,10,12). Pace et al (10) reported lower levels of patient satisfaction than the other two studies, although these studies varied in methodology: Engels et al (8) reported the proportion of patients who were ‘satisfied’; and Pace et al (10) and Hansen et al (12) reported the proportion of patients who were ‘satisfied’ and ‘very satisfied’. In addition, Engels et al (8) and Pace et al (10) included only patients with mild reflux esophagitis and those without, whereas Hansen et al (12) did not perform endoscopy; therefore, their study may have included patients with moderate and severe reflux esophagitis. In contrast, a fourth trial, which was performed exclusively on patients without reflux esophagitis (11), showed no significant difference between treatment groups in terms of the rate of satisfaction with treatment at six months (on-demand 82% versus continuous therapy 86%).

Surveys:

Eight studies used surveys to assess treatment satisfaction in patients with GERD. The patient satisfaction scales used in three studies had five categories (22–24), and one study had 11 categories (25). Four studies used a dichotomous response – a positive or negative response to being ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ (26–29).

Two studies compared patient satisfaction with prescription medication and over-the-counter (OTC) medication, and reported that patients with GERD were more satisfied with prescription medications than with OTC treatments (27,29). The prescription drugs reported by Bretagne et al (29) were PPIs (69%); antacids/alginates (46%); prokinetics (16%); and H2RAs (5.7%), but the OTC drugs were not specified. The study by Shaker et al (27) did not specify the types of prescription or OTC medication used.

Four surveys specifically reported levels of patient satisfaction with PPIs (22–25). On average, weighted according to sample size, 82% (95% CI 73% to 90%) of patients were ‘satisfied’ and 62% (95% CI 48% to 75%) were ‘very satisfied’ with PPI treatment. The highest level of satisfaction was achieved with PPI treatment compared with H2RAs and prokinetics (Table 2). This was illustrated by the largest survey (n=11,064), which was performed in the United States by Crawley and Schmitt (22). They found that 82% of patients were ‘satisfied’ with their PPI treatment and 58% were ‘very satisfied’. The proportions of ‘satisfied’ and ‘very satisfied’ patients were lower for H2RAs (77% versus 46%, respectively) and prokinetics (73% versus 42%, respectively).

TABLE 2.

Surveys reporting patient satisfaction with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) medications

| Author (reference) | Study population |

Population, n |

Scale |

Defined as |

Treatment | Satisfied, % | Very or completely satisfied, % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | With symptoms | Receiving treatment | ‘Satisfied’ | ‘Very satisfied’ | ||||||

| Crawey and Schmidt (22) | Individuals with chronic heartburn | 11,064 | 11,064 | 11,064 | 5-point scale (totally satisfied to totally unsatisfied) | 1–2 | 1 | PPI | 82 | 58 |

| H2RA | 77 | 46 | ||||||||

| Prokinetics | 73 | 42 | ||||||||

| Louis et al (26) | General population | 2000 | 568 | 335 | – | Responded as satisfied | – | Antacids (44%) | 93* | – |

| H2RAs (7.8%) prokinetics (7.6%) | ||||||||||

| PPIs (6.3%) | ||||||||||

| Robinson et al (25) | Individuals taking PPIs | 400 | 400 | 400 | 11-point scale (extremely satisfied | – | 0 | PPI | – | 59 |

| Shaker et al (27) | Individuals with at least weekly heartburn | 1000 | 791 (nighttime heartburn) | 553 (of those with nighttime heartburn) | – | – | Responded as completely satisfied | Prescription (details of specific medication not reported) OTC | – | 42 |

| – | 29 | |||||||||

| Bommelaer et al (28) | Primary care patients | 8459 | 8459 | 8459 | – | Responded as satisfied | – | PPI (98%) | 81* | – |

| Prokinetics (4%), Antacids/alginates (5%) | ||||||||||

| Bretagne et al (29) | General population | 8000 | 419 | 331 | – | Responded as completely or moderately satisfied | Responded as completely satisfied | Prescription (69% PPI, 46% antacid/alginates, 16% prokinetics and 5.7% H2RAs) or OTC | 97 | 67 |

| Dorval et al (23) | Primary care patients | 5326 | 5326 | 5326 | 5-point scale | – | Good or excellent | PPI | 72 | – |

| Chey et al (24) | GERD or reflux esophagitis diagnosis using prescription PPIs | 1347 | 1347 | 617 | 5-point scale | 1–2 | 1 | Prescription PPI; 42% supplemented PPIs with OTC or other prescription GERD medication | 73 | 38 |

Reported as an overall proportion for all treatment groups combined. H2RA Histamine type 2 receptor antagonist; OTC Over the counter; PPI Proton pump inhibitor

Relationship between patient satisfaction, symptom resolution and HRQoL

Twelve studies reported on the relationship between patient satisfaction and either symptom resolution or HRQoL. Two articles described validation studies of two different, GERD-specific, treatment satisfaction questionnaires, and showed a significant correlation between increased satisfaction, symptom resolution and improved HRQoL (30,31). The first study used the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire-GERD (TSQ-G) to assess 198 patients with GERD (30). The satisfaction subscale of the TSQ-G showed significant correlations with scores obtained on the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale and Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia questionnaire (QOLRAD) (r=0.26 to r=0.66 [all P<0.0001]). The second performed an Internet-based survey of 2511 individuals taking PPIs or H2RAs to validate the GERD Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (G-TSQ) (31). There were slight but significant correlations between G-TSQ scores and the presence of reflux symptoms (r=0.25 to r=0.43).

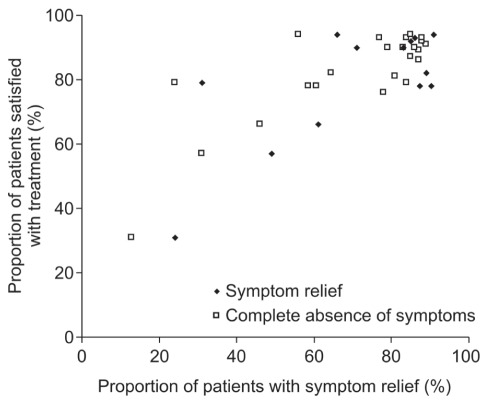

Satisfaction with improvement in reflux symptoms was compared in seven of the clinical trials reporting the percentage of patients satisfied with treatment, as shown in Figure 2. Five of these seven trials reported treatment satisfaction compared with both complete symptom resolution and symptom relief (8,9,16–18). The other two trials (12,15) reported only the complete absence of symptoms compared with satisfaction. Thus, Figure 2 depicts 15 treatment groups for symptom relief and 24 treatment groups for symptom resolution. A correlation between patient satisfaction and symptom relief is indicated at the aggregated study level (8,9,12,15–18). Overall, the proportion of satisfied patients increased as the proportion of patients with symptom relief increased. In most of the treatment groups analyzed (12 of 15), the proportion of patients satisfied with their treatment was higher than the proportion who experienced symptom relief by an average (weighted according to sample size) of 11% (95% CI 2.4% to 18.9%). Similarly, in most of the treatment groups analyzed (20 of 24), the proportion of patients satisfied with their treatment was higher than the proportion who experienced complete symptom resolution by an average (weighted according to sample size) of 10.6% (95% CI 2.2% to 19.0%).

Figure 2).

Comparison of treatment satisfaction with the resolution and relief of symptoms (data from references 8,9,12,15–18)

Two studies assessed the relationship between satisfaction and a range of other quality of life factors. Degl’Innocenti et al (19) performed a multiple linear regression analysis to assess the determinants of patient satisfaction with treatment. Higher baseline vitality scores in the QOLRAD, greater severity of heartburn at baseline and greater change in QOLRAD vitality score were associated with higher levels of satisfaction (all P<0.001).

Bretagne et al (29) compared satisfaction in patients with frequent or occasional reflux symptoms (heartburn and/or regurgitation) at baseline and found a negative correlation between the frequency of reflux symptoms and the degree of satisfaction. Compared with individuals with occasional reflux symptoms, significantly fewer patients with frequent reflux symptoms were completely satisfied with prescription treatments (75% versus 64% [P<0.001]), which were primarily PPIs (69% of patients with frequent symptoms versus 37% for occasional symptoms) and/or antacids/alginates (46% versus 55%), and less often H2RAs (6% versus 11%) or prokinetics (16% versus 15%).

DISCUSSION

Although the treatment of GERD has three main goals – symptom control, the healing of reflux esophagitis and the prevention of complications – symptom control may be the most important from the patient’s perspective. Long-term management is often required to sustain symptom control, which may be continuous maintenance treatment (daily dosing of acid suppressive therapy) or on-demand therapy (with medication taken only on the days that symptoms occur, until the symptoms subside). There is convincing evidence in the literature that PPIs are superior to H2RAs for symptom control and healing of reflux esophagitis (32). PPIs are also effective when given daily or on-demand in patients with GERD without reflux esophagitis and in those with uninvestigated GERD (33).

Patient satisfaction with treatment is a valuable outcome because it is a major determinant of the patient’s willingness to continue taking the required medication. It is influenced by many factors, including treatment regimen, general well-being of the patient, the bedside manner of the physician, and the quality of communication between the patient and their physician (34). The present review has identified an association between overall symptom relief and patient satisfaction, and between patient satisfaction and improvement in HRQoL. Similar associations between treatment satisfaction, treatment efficacy and HRQoL have been observed in other chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus (35) and osteoarthritis (36).

The correlation between HRQoL and satisfaction is a notable finding of the present review because patient satisfaction can be determined by posing a single question, unlike multidimensional instruments designed to understand treatment effects on HRQoL. Although HRQoL instruments are valuable secondary outcome measures in clinical trials, they are time consuming to administer and, hence, not practical in everyday practice. Instead of using an HRQoL questionnaire, perhaps a single question about satisfaction could be used in addition to questions about the control of specific symptoms.

The present systematic review demonstrates that the highest levels of patient satisfaction with GERD treatment are observed for PPIs compared with other GERD medications. Both of the RCTs that compared PPIs with H2RAs (12,17) showed superior levels of satisfaction with PPIs. No RCTs compared PPIs with prokinetic agents, although the survey data showed that satisfaction levels for PPIs were higher than both H2RAs and prokinetics. This is in agreement with trial efficacy data comparing PPIs, H2RAs and prokinetics reviewed by others (37,38). Thus, this suggests that higher patient satisfaction correlates with the greater acid control provided by PPIs than by other medications.

The data support the concept that when patients achieve complete or near complete control of their GERD symptoms, their satisfaction with treatment is high. Although PPIs were shown to decrease the frequency and severity of heartburn, only one trial specifically investigated whether there was a correlation between patient satisfaction after treatment and the severity of heartburn at baseline (19). This study did indeed find that these two factors were correlated. In addition, one survey documented a negative correlation between satisfaction and the frequency of heartburn and/or regurgitation at baseline (29). However, some patients experienced residual symptoms while on treatment. Moreover, data from several RCTs suggest that symptom control and patient satisfaction are lower with on-demand therapy than with continuous maintenance therapy, suggesting that satisfaction with PPI therapy is reduced in the presence of residual symptoms. This would be a justification for adjusting patient medication, for example, by increasing the dose of PPIs (39,40). Partial response to PPIs may also indicate that factors other than acid reflux are contributing to symptoms. These include functional dyspepsia (41), weakly alkaline or weakly acidic reflux (42–44), esophageal hypersensitivity or a combination of these factors (45).

Although surveys can be less reliable sources of data than RCTs, they provide insight into the patient’s perspective of treatment in real-life clinical practice. In surveys, the proportion of patients ‘satisfied’ with PPIs tended to be lower than that reported in trials. This difference suggests that patients with a partial response to PPI treatment are more common in unselected populations than in clinical trials. Adherence may also play a role because trials strongly encourage adherence through intensive follow-up – unlike real-life practice. Adherence has been shown to be related to satisfaction in the management of diabetes mellitus, in which lower adherence (eg, difficulty attending follow-up or taking medications [P<0.001]) was associated with lower treatment satisfaction (46).

The relationship between patient satisfaction and the clinical end point of symptom resolution was also analyzed. A correlation between satisfaction and symptom control and resolution was documented, although the proportion of satisfied patients was approximately 10% higher than either end point. A recent workshop on the study design of GERD trials (7) recommended that the absence or near complete relief of previously troublesome symptoms be used to measure treatment efficacy. The data support that patient satisfaction is also of use in assessing the effectiveness of treatment. One interpretation may be that patients can be satisfied despite the persistence of some symptoms, although this was not analyzed in any detail. Interestingly, the same workshop (7) recommended that a validated measure of patient satisfaction should be considered as a primary outcome measure in on-demand studies.

Although high levels of satisfaction with PPIs were reported in many trials, in some cases, a substantial proportion of patients were ‘not very satisfied’ with their treatment. In real-life clinical practice, as illustrated by the surveys reviewed in the present article, more than one-half of patients were less than completely satisfied with their prescription treatment, and up to one-half of patients who were prescribed PPIs used concomitant OTC remedies to control break through symptoms. This suggests that there is still an unmet need for effective treatment in some patients, which requires further study.

A detailed exploration of the relationship between heartburn scores and patient satisfaction among the studies was limited because no trials specifically stratified patient satisfaction according to this variable. Similarly, symptom relief from PPIs has been demonstrated to be highly predictive of reflux esophagitis healing (47); however, correlations between healing and satisfaction could not be performed in the present review because the proportions of patients satisfied after treatment were not described separately for different grades of esophagitis at baseline.

Most of the included studies did not use validated treatment satisfaction questionnaires, although the face validity of many of the instruments used was high. Validated questionnaires to measure patient satisfaction with GERD treatment are now available (30,31), and use of these in future studies of GERD treatment would enable comparison among studies and further pooling of data for meta-analysis.

The present review had several limitations. The studies used inconsistent thresholds for the severity of GERD symptoms at baseline, although most studies used a baseline severity of at least two to four episodes of heartburn per week. There was also variation among studies in the methods used to measure patient satisfaction. Hence, these differences among studies are described in the review and the data were interpreted with this caveat in mind. In addition, the methods used to measure satisfaction in the studies are likely to result in substantial acquiescent response bias (tendency of individuals to agree with questions), particularly in older respondents, those with less education and those in poorer health (48). The use of attitude response scales (such as ‘very satisfied’ to ‘very dissatisfied’) skews individual responses to satisfaction questions and inflates reliability estimates (48). Patients could also interpret the word ‘satisfaction’ variably, reducing the comparability of the results. A study by Vakil et al (49) indicated that symptom questionnaires using continuous rather than binary variables were easier for patients to understand. It was suggested that terms should be more descriptive, for example, ‘satisfactory relief’ could be replaced with ‘at least partial relief’. Hence, as used in three of the studies (8,15,16), a ‘positive response’ to assess levels of satisfaction may have been less clear to the patients than the use of rating scales. Future studies that use multi-item scales that include balanced positively and negatively worded items may increase score variability and reliability in satisfaction research because they are subject to less acquiescent response bias than studies using attitude response scales (48).

The FDA has recently finalized guidance for the development of instruments measuring patient-reported outcomes for use in clinical trials to support label claims (6). The guidelines emphasize the importance of patient input and incorporating patient feedback in the development of questionnaires and reflect the increasing prominence of assessing the patient experience with treatment. Furthermore, compared with patients, physicians tend to overestimate the benefit of PPI treatment in GERD (50). Thus, assessing patient satisfaction with treatment should enable a more comprehensive understanding of disease and treatment response than the traditional reliance on objective disease markers, particularly in patients with GERD without reflux esophagitis because the response to treatment is the main outcome measure.

Insight into patient satisfaction may be particularly valuable when the primary outcomes of clinical trials are similar for two treatments. The present systematic review has shown that patient satisfaction correlates with symptom resolution, a primary outcome of clinical trials, and with HRQoL, a secondary measurement of therapeutic success. It would be of great interest for future studies to report how patient satisfaction relates to other clinical end points, such as patient satisfaction individually reported according to the healing of reflux esophagitis, prevention of relapse and adverse effects, in additon to more studies examining satisfaction and changes in individual symptoms such as heartburn frequency and severity.

CONCLUSION.

The patient’s evaluation of their treatment is becoming increasingly important to medical care, particularly for the management of chronic disease. Future research, with a focus on uniformity in the measurement of satisfaction, and further investigation into the relationship between satisfaction and other clinical end points, could contribute to improved patient care and long-term treatment success.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: This study was funded in full by AstraZeneca R&D, Mölndal, Sweden. Dr Sander Veldhuyzen van Zanten has received research support or speakers honoraria from, and/or served on advisory boards for Abbott, AstraZeneca, Janssen-Ortho, Nycomed and Takeda. Dr Catherine Henderson and Dr Nesta Hughes are employees of Oxford PharmaGenesis Ltd.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vakil N, Veldhuyzen van Zanten S, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) – a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, et al. Gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms and health-related quality of life in the adult general population – the Kalixanda study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1725–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irvine EJ. Quality of life assessment in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut. 2004;53(Suppl 4):iv35–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.034314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talley NJ, Wiklund I. Patient reported outcomes in gastroesophageal reflux disease: An overview of available measures. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:21–33. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-0613-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dent J, Armstrong D, Delaney DC, Moayyedi P, Talley NJ, Vakil N. Symptom evaluation in reflux disease: Proceedings of a workshop held in Marrakech, Morocco. Gut. 2004;53(Suppl 4):iv1–65. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.034272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Guidance for Industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims. 2009. < www.ispor.org/workpaper/FDA%20PRO%20Guidance.pdf> (Accessed on May 13, 2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Dent J, Kahrilas PJ, Vakil N, et al. Clinical trial design in adult reflux disease – a methodological workshop. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:107–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engels L, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Dekkers C, et al. Esomeprazole continuous versus on demand maintenance therapy in 1052 gastro-oesophageal reflux patients: Similar satisfaction but superior quality of life for once daily treatment. Gut. 2003;52(Suppl VI):A130. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai HH, Chapman R, Shepherd A, et al. Esomeprazole 20 mg on-demand is more acceptable to patients than continuous lansoprazole 15 mg in the long-term maintenance of endoscopy-negative gastro-oesophageal reflux patients: The COMMAND Study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:657–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pace F, Negrini C, Wiklund I, Rossi C, Savarino V. Quality of life in acute and maintenance treatment of non-erosive and mild erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:349–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bayerdorffer E, Bigard MA, Weiss W, et al. On-demand versus continuous treatment with esomeprazole 20 mg daily in non-erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: An international, randomised, multicentre study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (In press) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen AN, Bergheim R, Fagertun H, Lund H, Wiklund I, Moum B. Long-term management of patients with symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease – a Norwegian randomised prospective study comparing the effects of esomeprazole and ranitidine treatment strategies on health-related quality of life in a general practitioners setting. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:15–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2006.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cibor D, Ciecko-Michalska I, Owczarek D, Szczepanek M. Optimal maintenance therapy in patients with non-erosive reflux disease reporting mild reflux symptoms – a pilot study. Adv Med Sci. 2006;51:336–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meineche-Schmidt V, Hauschildt Juhl H, Ostergaard JE, Luckow A, Hvenegaard A. Costs and efficacy of three different esomeprazole treatment strategies for long-term management of gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms in primary care. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:907–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulder CJ, Westerveld BD, Smit JM, et al. A double-blind, randomized comparison of omeprazole multiple unit pellet system (MUPS) 20 mg, lansoprazole 30 mg and pantoprazole 40 mg in symptomatic reflux oesophagitis followed by 3 months of omeprazole MUPS maintenance treatment: A Dutch multicentre trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:649–56. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200206000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lind T, Havelund T, Carlsson R, et al. Heartburn without oesophagitis: Efficacy of omeprazole therapy and features determining therapeutic response. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:974–9. doi: 10.3109/00365529709011212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bate CM, Green JR, Axon AT, et al. Omeprazole is more effective than cimetidine for the relief of all grades of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-associated heartburn, irrespective of the presence or absence of endoscopic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:755–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eggleston A, Katelaris PH, Nandurkar S, Thorpe P, Holtmann G. Clinical trial: The treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in primary care – prospective randomized comparison of rabeprazole 20 mg with esomeprazole 20 and 40 mg. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:967–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Degl’ Innocenti A, Guyatt GH, Wiklund I, et al. The influence of demographic factors and health-related quality of life on treatment satisfaction in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease treated with esomeprazole. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:4. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathias SD, Colwell HH, Miller DP, et al. Health-related quality-of-life and quality-days incrementally gained in symptomatic nonerosive GERD patients treated with lansoprazole or ranitidine. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:2416–23. doi: 10.1023/a:1012363501101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ponce J, Arguello L, Bastida G, Ponce M, Ortiz V, Garrigues V. On-demand therapy with rabeprazole in nonerosive and erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease in clinical practice: Effectiveness, health-related quality of life, and patient satisfaction. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:931–6. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000034551.39324.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crawley JA, Schmitt CM. How satisfied are chronic heartburn sufferers with their prescription medications? Results of the patient unmet needs survey. J Clin Outcomes Manage. 2000;7:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dorval E, Rey J, Barthelemy P, Caekaert A, Soufflet C. Assessment of satisfaction following the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux by proton pump inhibitors in primary care: The REFLEX physician-patient agreement study. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(4 Suppl 2):T1019. (Abst). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chey WD, Mody RR, Wu EQ, et al. Treatment patterns and symptom control in patients with GERD: US community-based survey. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:1869–78. doi: 10.1185/03007990903035745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robinson M, Shaw K. Proton pump inhibitor attitudes and usage: A patient survey. Pharm Ther J. 2002;27:202–6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Louis E, DeLooze D, Deprez P, et al. Heartburn in Belgium: Prevalence, impact on daily life, and utilization of medical resources. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:279–84. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200203000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaker R, Castell DO, Schoenfeld PS, Spechler SJ. Nighttime heartburn is an under-appreciated clinical problem that impacts sleep and daytime function: The results of a Gallup survey conducted on behalf of the American Gastroenterological Association. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1487–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bommelaer G, Caekaert A, Barthelemy P. Management of gastro-oesophageal reflux in primary care at the time of diagnosis. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(4 Suppl 2):A382. (Abst). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bretagne JF, Honnorat C, Richard-Molard B, Caekaert A, Barthelemy P. Comparative study of characteristics and disease management between subjects with frequent and occasional gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:607–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coyne KS, Wiklund I, Schmier J, Halling K, Degl’ Innocenti A, Revicki D. Development and validation of a disease-specific treatment satisfaction questionnaire for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:907–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shikiar R, Flood E, Siddique R, Howell J, Dodd SL. Development and validation of the gastroesophageal reflux disease treatment satisfaction questionnaire. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:2025–33. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-3002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chiba N, De Gara CJ, Wilkinson JM, Hunt RH. Speed of healing and symptom relief in grade II to IV gastroesophageal reflux disease: A meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1798–810. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9178669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pace F, Tonini M, Pallotta S, Molteni P, Porro GB. Systematic review: Maintenance treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease with proton pump inhibitors taken ‘on-demand’. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:195–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bytzer P. What makes individuals with gastroesophageal reflux disease dissatisfied with their treatment? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:816–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weaver M, Patrick DL, Markson LE, Martin D, Frederic I, Berger M. Issues in the measurement of satisfaction with treatment. Am J Manag Care. 1997;3:579–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altman RD, Rosen JE, Bloch DA, Hatoum HT, Korner P. A double-blind, randomized, saline-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of EUFLEXXA for treatment of painful osteoarthritis of the knee, with an open-label safety extension (the FLEXX trial) Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009;39:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Pinxteren B, Numans ME, Bonis PA, Lau J. Short-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists and prokinetics for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-like symptoms and endoscopy negative reflux disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD002095. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002095.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donnellan C, Sharma N, Preston C, Moayyedi P. Medical treatments for the maintenance therapy of reflux oesophagitis and endoscopic negative reflux disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(4):CD003245. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003245.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bajbouj M, Becker V, Phillip V, Wilhelm D, Schmid RM, Meining A. High-dose esomeprazole for treatment of symptomatic refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease – a prospective pH-metry/impedance-controlled study. Digestion. 2009;80:112–8. doi: 10.1159/000221146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bate CM, Booth SN, Crowe JP, Hepworth-Jones B, Taylor MD, Richardson PD. Does 40 mg omeprazole daily offer additional benefit over 20 mg daily in patients requiring more than 4 weeks of treatment for symptomatic reflux oesophagitis? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1993;7:501–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1993.tb00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kusano M, Shimoyama Y, Kawamura O, et al. Proton pump inhibitors improve acid-related dyspepsia in gastroesophageal reflux disease patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1673–7. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9674-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mainie I, Tutuian R, Shay S, et al. Acid and non-acid reflux in patients with persistent symptoms despite acid suppressive therapy: A multicentre study using combined ambulatory impedance-pH monitoring. Gut. 2006;55:1398–402. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.087668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weigt J, Monkemuller K, Peitz U, Malfertheiner P. Multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH-metry for investigation of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis. 2007;25:179–82. doi: 10.1159/000103881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zerbib F, Roman S, Ropert A, et al. Esophageal pH-impedance monitoring and symptom analysis in GERD: A study in patients off and on therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1956–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fass R, Sifrim D. Management of heartburn not responding to proton pump inhibitors. Gut. 2009;58:295–309. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.145581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Biderman A, Noff E, Harris SB, Friedman N, Levy A. Treatment satisfaction of diabetic patients: What are the contributing factors? Fam Pract. 2009;26:102–8. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmp007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gillessen A, Beil W, Modlin IM, Gatz G, Hole U. 40 mg pantoprazole and 40 mg esomeprazole are equivalent in the healing of esophageal lesions and relief from gastroesophageal reflux disease-related symptoms. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:332–40. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200404000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Revicki DA. Patient assessment of treatment satisfaction: Methods and practical issues. Gut. 2004;53(Suppl 4):iv40–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.034322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Chang L, et al. Comprehension and awareness of symptoms in women with dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:1147–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fallone CA, Guyatt G, Armstrong D, et al. How well do physicians assess patient symptom severity and health related quality of life (HRQL) in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)? Gut. 2004;53(Suppl 6):A100. [Google Scholar]