Abstract

Major noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) share common behavioral risk factors and deep-rooted social determinants. India needs to address its growing NCD burden through health promoting partnerships, policies, and programs. High-level political commitment, inter-sectoral coordination, and community mobilization are important in developing a successful, national, multi-sectoral program for the prevention and control of NCDs. The World Health Organization's “Action Plan for a Global Strategy for Prevention and Control of NCDs” calls for a comprehensive plan involving a whole-of-Government approach. Inter-sectoral coordination will need to start at the planning stage and continue to the implementation, evaluation of interventions, and enactment of public policies. An efficient multi-sectoral mechanism is also crucial at the stage of monitoring, evaluating enforcement of policies, and analyzing impact of multi-sectoral initiatives on reducing NCD burden in the country. This paper presents a critical appraisal of social determinants influencing NCDs, in the Indian context, and how multi-sectoral action can effectively address such challenges through mainstreaming health promotion into national health and development programs. India, with its wide socio-cultural, economic, and geographical diversities, poses several unique challenges in addressing NCDs. On the other hand, the jurisdiction States have over health, presents multiple opportunities to address health from the local perspective, while working on the national framework around multi-sectoral aspects of NCDs.

Keywords: Health promotion, mainstreaming, multi-sectoral partnerships, noncommunicable diseases, social determinants of NCDs

NCD Burden in India

In the past few decades, India has undergone rapid epidemiologic, demographic, nutritional and economic transitions, which have brought about the “dual burden” of diseases. While India is witnessing declining trends in morbidity and mortality from communicable diseases, there has been a gradual increase in the prevalence of chronic noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), such as cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cancers, injuries, and mental health disorders. India currently accounts for about 17% of the world population(1) and contributes to about fifth of the world's share of diseases and an equal proportion of nutritional deficiencies, diabetes, and CVDs among all NCDs.(2) Projections suggest that NCDs in India would rise from 3.78 million in 1990s to 7.63 million in 2020.(3) In 2005, NCDs accounted for 53% of the total deaths (10.3 million) and 44% (291 million) of the disability adjusted life years (DALYs) lost in India.(4) It is expected that CVD-attributable deaths will reach 4 million by 2030.(5,6) Evidence suggests that NCDs disproportionately impact people at younger ages(7,8) and are increasingly afflicting the poorer segments of the Indian population.(9,10) It imposes huge social and economic costs, impeding not only health improvements but also economic progress and social development of the country.(11)

Risk Factors Associated with NCDs

Compared to infectious diseases, the causes of NCDs are complex in nature as these diseases have multi-factorial causation. Several risk factors are associated with the incidence of NCDs including physical environment, biological, behavioral and socio-economic (local, national, global) factors. Individual risk factors (non-modifiable) including age, sex and genetics and behavioral risk factors (modifiable) such as alcohol consumption, tobacco use, lack of physical activity and unhealthy foods contribute to the development of NCDs.(12) The major NCDs are preventable as they are primarily caused by modifiable behavioral risk factors. Other risk factors associated with NCDs are referred to as “social determinants” pertaining to economic and social causes.

Social Determinants Associated with NCDs

Rising population and socio-economic transition in the country have led to rapid urbanization and unplanned expansion of cities, as more and more people are migrating from rural areas to urban centers in search of better livelihood opportunities. “This has placed increased demand on urban infrastructure, services and public places, leading to upsurge in disease burden through increased susceptibility to risks for NCDs”.(13) Following these changes in the socio-economic environment of individuals, risk factors for NCDs have become widespread.(14) Market liberalization and agricultural subsidies have made unhealthy products easily available at reduced prices, which are causing negative health outcomes.(15)

Some of the behavioral risk factors of NCDs are closely interlinked to poverty, low education, poor diet, inequitable access to health services, and gender disparity. Diabetes (particularly type 2) was previously seen as a disease of affluence, which now seem misleading, as approximately 70% of the world's diabetic people live in low and middle income countries, with high prevalence in world's poorest cities, where access to health care and social support is either not available, or is very limited.(16) Low intake of fruits and vegetables and lower levels of physical activity coupled with unhealthy food consumption is now being witnessed among the urban poor in India.(17) Tobacco, seen as the single largest preventable risk factor,(18,19) disproportionately affects the poor and the less educated.(20) The inequities in vulnerability and exposure to tobacco use (social, psychological, health status, exposure to tobacco through advertising, lack of cessation services) is clearly evident, and often leads to prolongation of tobacco use among the adolescents and adults from poor socio-economic backgrounds.(21) In the case of mental disorders, the risk is determined by an interface of genetic, biological, social, psychological factors. Increased rates of depression are associated with NCDs, and socio-economically disadvantaged groups bear uneven burden of negative health outcomes, with poor access to mental health services.(22) Evidence gathered so far indicates higher burden of alcohol-attributable disease among people of lower socio-economic sections, despite lesser overall consumptions levels, as health outcomes depend not only on the amount but also on the type and quality of alcohol consumed.(23)

High NCD mortality in India, which is attributed among other reasons to a weak health system, leads to high and many a times catastrophic out-of-pocket expenditure on health.(18) For a country like India, which is facing scarce resources, prevention of diseases, particularly NCDs that are expensive to treat, is the most cost-effective strategy.(2) India spent nearly INR 846 billion out of pocket on health care expenses in the year 2004, amounting to 3.3% of India's Gross domestic product (GDP) for that year. This marked a substantial increase from INR 315 billion spent out of pocket on health care in the year 1995-96 (about 2.9% of India's GDP in the year 1995-96).(11) Out of this, a total out of pocket health expenditure on NCDs including heart diseases, hypertension, respiratory diseases, orthopedic problems, kidney diseases, neurological disorders, cancer, accidents, and injuries was INR 99.61 billion in 1995-1996, which has increased to INR 400.31 billion in 2004. Access to basic health care in itself is a challenge in India and contributes to health inequalities as this is mainly influenced by wider social determinants of health and infrastructural support.(24) Thus, combating NCDs requires effectively addressing these social determinants of health, through comprehensive action focusing on prevention and control of NCDs.

Multi-sectoral Action for NCD Prevention and Control

Given that inequities in NCDs manifest themselves in the form of differential health consequences, due to varied exposure, social stratification, and differential vulnerability, action is needed from health as well as allied sectors.(25) This may require structural and policy level interventions, which address issues that lie outside the health domain, but have a strong bearing on achieving positive health outcomes for the communities. Thus, aligning the NCD effort with the health and development agenda at all levels will help address these challenges. Addressing challenges through creation and utilization of opportunities for collaboration in health and exploring innovative ways of working together to achieve accelerated response to NCDs by achievement of health and development goals form the basis of multi-sectoral partnerships.

For instance, the mid-day meal scheme of the Ministry of Human Resource Development (Education) can be effectively utilized to provide healthy food to 120 million children in underprivileged sections of the society.(26) This will not only ensure nutrition for healthy growth (physical and cognitive), but will also help in forming healthy food habits. National Schemes like the ‘Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act’ under the Ministry of Rural Development aims to enhance the livelihood security of people in rural areas, can be strengthened to address the social determinants of rural health.(27)

Thus, innovative partnerships whereby every sector of relevance reviews and reforms with a goal to reduce the risk factors that predisposes the public to the NCDs and their socio-economic after effects, through a spectrum of interventions ranging from health promotion, to providing affordable medication, access to quality health care to rehabilitation of the survivors is critical.

Whole-of-Government approach to the development of a “National Multi-sectoral Framework for the Prevention and Control of NCDs” is recommended under the WHO 2008-2013 Action Plan for the Global Strategy for prevention and control of NCDs.(28) Inter-sectoral coordination will need to start at the planning stage and continue to the implementation, evaluation of interventions and enactment of public policies. An efficient multi-sectoral mechanism is also crucial at the stage of monitoring, evaluating enforcement of policies, and analyzing impact of multi-sectoral initiatives on reducing NCD burden in the country.

More recently, the “Delhi Call for Action on Partnerships for Health” adopted at the “Partners for Health in South-East Asia Conference,” in March 2011 in New Delhi calls for a commitment to create, revitalize and sustain partnerships through aligned and integrated action in consonance with national development priorities.(18) Multi-sectoral action requires partnerships within Government and with non-Government stakeholders. Multi-sectoral policies can be addressed through partnerships within health sector and with other departments within Government and Inter-Governmental organizations.(29) Community is core to any health intervention, and is an important partner in delivering interventions, such as spreading health messages, advocacy for better access to information and services and ground level monitoring of the efforts.(18) Other stakeholders include the private sector and foundations, NGOs and civil society, UN organizations, and the media. Mainstreaming requires NCDs to be included in the agendas of Heads of States and Governments, so that health is viewed as a worthwhile investment and not merely as expenditure. In the present context, adopting an integrated approach to prevention and control of NCDs will require piggybacking on existing systems instead of creating parallel systems. This will ensure resource sharing for priority interventions, and will avoid burdening the health systems any further.

International Experiences in Multi-sectoral Partnerships to Combat NCDs

Finland's community-based CVD prevention project (North Karelia Project)(30)

It is a well-published model that successfully lowered risk factors associated with CVD at the population level, utilizing a multi-sectoral approach. This comprehensive intervention involved community health education and empowerment, improved health services delivery, prevention efforts in multiple settings (schools, workplaces), media partnership, with greater involvement of civil society and the private sector. Health promoting public health policies too had a critical role in this success through regulating food labeling, tobacco regulations, and shifting agricultural subsidies to encourage low-fat alternatives.

Singapore's health promotion board

Established in 2001, coordinates national health promotion efforts and disease management programs to reduce NCDs, by engaging multiple sectors.(31) It adopts a settings based approach for health promotion activities to prevent NCDs, complemented by screening and treatment of those with clinical diseases. Public education through media, food labeling, and tobacco control policies has facilitated adoption and practice of healthy choices by communities.(32) The National Health Commission (NHC) in Thailand is a cross-sectoral mechanism that is chaired by the Prime Minister and comprises of three broad sectors-government, academia and civil society-to emphasize health promotion and support development of Healthy Public Policies (HPP).(18)

National Experiences of Multi-sectoral Partnerships

Multi-sectoral mechanisms for the implementation of tobacco control laws

Tobacco control provides a good example for the need and the potential impact of multi-sectoral action in NCD prevention and control. Effective tobacco control involves not only addressing it at the individual level (preventing use by individuals, helping users to quit) but also leveraging multi-sectoral approaches to address production, trade, taxation, and implementation of tobacco control laws. The implementation of the international tobacco control treaty, Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), requires and obligates the participation of sectors beyond health in achieving its goals. In India, an “Inter-ministerial Task Force for Tobacco Control” exists, under the aegis of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) that has participants from ministries including: Labour, Commerce, Information and Broadcasting, Agriculture, Ministry of Rural Development, Department of Revenue, Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion, Food Standards and Safety Authority of India; Drug Controller General of India and civil society members among others. A Steering Committee that facilitates the enforcement of tobacco advertising ban exists at National, State, and District levels. This Committee at the center includes members representing Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Ministry of Law and Justice and NGO members from multi-disciplinary backgrounds.

Multi-sectoral project for HIV/AIDS prevention

The Red Ribbon Express project of National AIDS Control Organization presents one successful model of partnership comprising of Government (Ministries of Railways, Social Welfare, AIDS Control Organization) and Non-Governmental stakeholders (Rajiv Gandhi Foundation), intergovernmental bodies (UNAIDS and UNICEF), engaging national programs such as National Rural Health Mission and local governments (Panchayati Raj) to address a communicable disease.(33) The project drew on the strengths of its partners such as the Railways for mobility, Information and Broadcasting for publicity and UNICEF for communication strategy, thus proving cost-effective and resourceful.

Multi-sectoral Coordination Mechanism

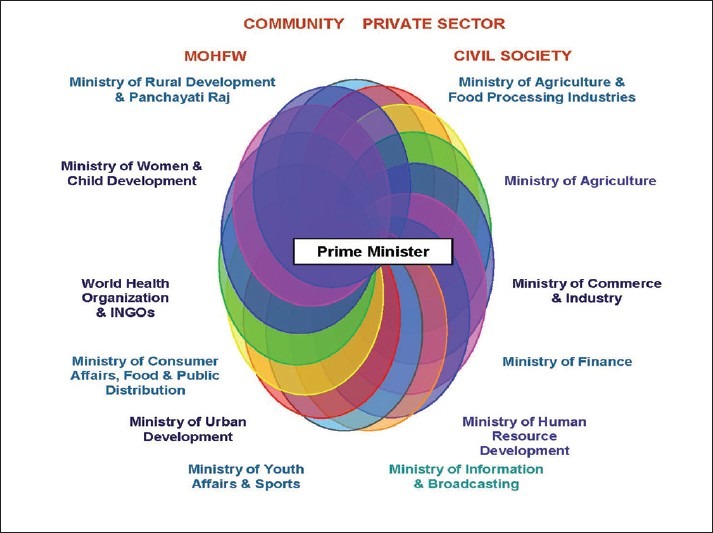

A comprehensive multi-sectoral action on NCDs in India requires a partnership approach that combines action of all relevant stakeholders. Thus a “Whole of Government” or “Health in all Government policies” approach to influence public health policy is required, by engaging multiple government ministries such as Health, Finance (Excise and Taxes), Home, Education, Agriculture, Civil Supplies, Food Processing, Urban and Rural Development, Transport, Women and Child Development, Commerce, Environment, Local self-government and Panchayati Raj,Information and Broadcasting. In addition, participation of civil society organizations, private healthcare sector, media, and donor organizations, is equally important to devise policies and programs which will find wide acceptability, an essential criterion for successful implementation. This proposed mechanism is presented in Figure 1, with clear intersections to work on NCD control and Prime Minister at the core of this mechanism to ensure smooth coordination. NGOs provide the connectivity between Government programs and the community and have a strong role to contribute in this multi-sectoral mechanism.

Figure 1.

Model for a multi-sectoral partnership with political commitment

A key factor in deciding the partners for a multi-sectoral initiative is the agreement on its goals and excluding those with conflicting interests. For instance, certain players in the private sector with no conflicting interest can be engaged in promoting healthy diet and physical activity, limiting levels of saturated fats, trans-fatty acids, high sugars and salt, increasing availability of healthy and nutritious food choices, and reviewing current market practices. Example for a clear case for explicit exclusion from such partnership would be the alcohol and the tobacco industries. India being a ratifying party to the FCTC, is bound by Article 5.3 of the treaty and is required to protect its public health policies pertaining to tobacco control from tobacco industry interests.(34)

Role of Health Promotion in Tackling NCDs

Health promotion is an effective process in tackling the underlying determinants of NCDs by enabling people and communities to increase control over the determinants of health and thereby improve their health.(35) It is an inclusive process, of social and political mobilization, to facilitate action at various levels for achieving improved health outcomes. Intervention activities can focus on risk reduction through life skills education, facilitating adoption of healthy life styles (creation of enabling and supportive environment to practice healthy behaviors through progressive policies, legislations, regulations), and availability of preventive health information and services.(36)

Health Promotion Interventions in India

Worksite wellness interventions in lowering risk of CVD in India

Sentinel surveillance system for CVD risk factors in the Indian Industrial Population was developed by Initiative for Cardiovascular Health Research in Developing Countries. This effort's key feature was a population-based approach of behavior change, implemented through a multicomponent, multilevel, and multi-method intervention, involving trained local healthcare personnel in the participating industries. This worksite-based health promotion initiative adopted a multi-sectoral approach by building partnerships between employees, healthcare personnel, and research institute providing health promotion intervention.

School health program

School-based educative programs can significantly influence children's behavior for inculcating healthy lifestyle practices. The school-based intervention, MARG (Medical education for children/Adolescents for Realistic prevention of obesity and diabetes and for healthy ageing) revealed a significant increase in the intake of healthy foods, reduced intake of fried and fatty energy dense foods, increased physical activity and time spent on outdoor games along with improvements in glycemic parameters and lipid profiles.(37)

HRIDAY-CATCH (Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health), 1996-1998, and MYTRI (Mobilizing Youth for Tobacco Related Initiatives in India), 2002–2007, were randomized controlled intervention trials that established the effectiveness of school health interventions in reducing tobacco use among Indian adolescents by reducing current tobacco use, reducing their future intentions to use tobacco, and by enhancing their health advocacy skills.(38,39) Such initiatives require partnerships between public health professionals, NGOs, students, parents, teachers, schools, department of education, and community.

Mainstreaming health promotion in national health and development agendas

Indian government has launched several initiatives for prevention and control of NCDs. This includes the National Cancer Control Programme (NCCP), the National Trauma Control program, the National Program for Control of Blindness, the National Mental Health Programme, the National Tobacco Control Program, and the National Program for Control of Diabetes, Stroke and Cardiovascular Diseases. Health Promotion is a common component in all these vertical programs. At sub-national levels, health being a state subject, states such as Tamil Nadu and Kerala have piloted efforts around NCD prevention and control, through various health promotion activities. However, to have a population level impact, and to reach communities in the periphery, NCD program efforts along with other health and development programs will have to mainstream health promotion as a core component.

While there is no universally accepted definition of mainstreaming, it is usually understood as a process whereby a sector analyses how diseases can impact it now and in the future, and subsequently considers how policies, decisions, and actions might influence the longer-term development of the diseases and the sector. Thus, the sector recognizes the relevance of disease conditions and takes action to address it internally and externally. Mainstreaming health promotion for NCDs is about modification of process from a vertical to a horizontal plane, from a lack of action toward a push, demand, and request for support and coordinated action and increased ownership. It is about a growing consciousness and culture toward integrating health promotion messages and interventions for NCDs.

Mainstreaming in the context of NCDs need to follow a dual approach for optimal outcomes. The first approach requires sectors that currently contribute to the NCD epidemic to review and revise their programs and practices with a view to mitigate the challenge. For instance, the processed food industry needs to reduce salt content in their products to reduce the risks for cardio-vascular diseases. Similarly, the Urban Planning Departments and Department of Transport would need to jointly replace existing infrastructure plans that promote the use of private transport with those that facilitate transportation of more people through faster, comfortable, and well-connected public transport network.

Secondly, sectors that bear the brunt of these diseases develop policies and practices that address the risk factors in order to contain its after effects. This could, for example, involve the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting legislating to regulate the promotion of unhealthy food or city corporations improving public transport system and thereafter increasing parking charges on car owners with a view to discourage the use of private transport.

Mainstreaming could help address NCDs from diverse directions, reduce the human and economic cost incurred to roll out programs that could provide universal access to health promotion, and care by leveraging the reach and strengths of diverse stakeholders and avoiding duplication.

Challenges and Opportunities for Mainstreaming NCDs

Challenges

Most non-health departments within the Government lack understanding of their role in NCD prevention and perceive this as strictly a health sector's domain, which shows lack of ownership for the issue and functioning in silos.

Lack of institutional arrangement and resources (financial, physical and technical) to work under a multi-sectoral arrangement.

Prioritizing one's own sector's program and activities due to existing work load.

Weak and fragmented health system does not reach the disadvantaged and marginalized populations.

A critical shortage of the public health workforce in India.

Knowledge gap and translation inhibits evidence-based decision making due to inadequate and underutilized health information systems.

Death and disease registries are not robust or available to inform policies and programs.

Opportunities

Innovative partnerships like the Wellcome Trust, the Roll Back Malaria Partnership, the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI), and the World Bank can be developed for NCD prevention and control.

Community's involvement for demanding better services, implementation of public health laws, and improving health outcomes has been effective.

Precedence exists for inter-ministerial task force on tobacco control. Broadening the functions of this task force to include health promotion for NCD prevention and control.

Government is committed to increase funding for NCD prevention programs.

Many state Governments are increasing taxes on tobacco products. Such approach can be used for increasing taxation on harmful products like alcohol and energy dense foods in partnership with Ministry of Finance, to subsidize healthy food options.

Indian pharmaceutical industry is strong and people are able to access NCD management drugs at affordable prices. Health care costs must be contained and catastrophic expenditure avoided through early screening and management, in partnership with existing strong private sector.

India has successful well-evaluated health promotion examples in various settings that can be up-scaled.

The mid-day meal program can be scaled up and improved to ensure healthy and nutritious food to children in underserved areas.

Conclusions

High political commitment

None of these would happen without political will and commitment at the highest level. Modeled along the lines of the UN Special Summit on HIV/AIDS of 2001 that led to the creation of UNAIDS agency and the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and National AIDS Programs in several countries, a UN Summit on NCDs held in the month of September 2011, witnessed the Heads of States adopting a Political Declaration to address the emerging epidemic. Time has come particularly for countries like India that has at stake its economic growth and productive workforce on account of escalating NCDs, to translate the global commitments to action at the national level.

Unlike the communicable diseases that are caused by pathogens, the risk factors for four of the major NCDs (tobacco and alcohol use, unhealthy diet, and lack of physical activity) are of human origin, propelled by corporate interests and spread through aggressive marketing. Therefore, risk-reduction policies are often resisted by businesses that contribute to the NCD burden. Firm political will and stern action is therefore required to prioritize public health and development ahead of trade interests.

Revitalizing primary health care will require decentralization, which can address health inequities and will depend upon achieving good governance, forming productive partnerships at all levels in the community, implementing a comprehensive approach to pro-poor growth, improving public services, coordination among stakeholders, and addressing the social determinants of health. Translating policy to action can be achieved only if there is a sense of ownership among all stakeholders involved in the development and implementation of healthy public policies.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burke J. Census reveals that 17% of the world is Indian. [Last accessed on 2011 Sep 29]. Available from: http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/mar/31/census-17-percent-world-indian .

- 2.Report of the National Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family and Welfare, Government of India; 2005. Ministry of Health and Family and Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Evidence-based health policy-lessons from the global burden of disease study. Science. 1996;274:740–3. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddy KS, Shah B, Varghese C, Ramadoss A. Responding to the threat of chronic diseases in India. Lancet. 2005;366:1744–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prabhakaran D, Ajay VS. Noncommunicable diseases in India: A perspective. World Bank. 2011 [In Press] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel V, Chatterji S, Chisholm D, Ebrahim S, Gopalakrishna G, Mathers C, et al. Chronic diseases and injuries in India. Lancet. 2011;377:413–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61188-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.A community based Integrated Program for control of Noncommunicable Diseases in Union Territory of Chandigarh (CHHAP) Project Report. Chandigarh: School of Public Health, PGIMER; 2007. PGIMER. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy KS, Prabhakaran D, Chaturvedi V, Jeemon P, Thankappan KR, Ramakrishnan L, et al. Methods for establishing surveillance system for cardiovascular diseases in Indian industrial population. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:461–9. doi: 10.2471/blt.05.027037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joshi P, Islam S, Pais P, Reddy S, Dorairaj P, Kazmi K, et al. Risk factors for early myocardial infarction in South Asians compared with individuals in other countries. JAMA. 2007;297:286–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddy KS, Prabhakaran D, Jeemon P, Thankappan KR, Joshi P, Chaturvedi V, et al. Educational status and cardiovascular risk profile in Indians. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16263–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700933104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahal A, Karan A, Engelgau M. The economic implication of NCD in India. Washington DC, USA: The World Bank; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mendis S, Banerjee A. Cardiovascular disease: equity and social determinants. In: Blas E, Kurup AS, editors. Equity, social determinants and public health programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. pp. 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohan S, Reddy KS, Prabhakaran D. Chronic noncommunicable diseases in India-reversing the tide. New Delhi: Public Health Foundation of India; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geneau R, Stuckler D, Stachenko S, McKee M, Ebrahim S, Basu S, et al. Raising the priority of preventing chronic diseases: A political process. Lancet. 2010;376:1689–98. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rayner G, Hawkes C, Lang T, Bello W. Trade liberalization and the diet transition: A public health response. Health Promot Int. 2006;21(Suppl 1):67–74. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dal053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whiting D, Unwin N, Roglic G. Equity, social determinants and public health programs. In: Blas E, Kurup AS, editors. Equity, social determinants and public health programs. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugathan TN, Soman CR, Sankaranarayanan K. Behavioral risk factors for noncommunicable diseases among adults in Kerala, India. Indian J Med Res. 2006;127:555–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Partners for Health, South-East Asia Conference Report. New Delhi, Geneva: Regional Office for South-East Asia, World Health Organization; 2011. WHO SEARO. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Tobacco Factsheet. 2011. [Last accessed on 2011 Oct 3]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en/index.html .

- 20.Subramanian SV, Nandy S, Kelly M, Gordon D, Smith GD. Patterns and distribution of tobacco consumption in India: Cross sectional multi-level evidence from the 1998-9 national family health survey. BMJ. 2004;328:801–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7443.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.David A, Esson K, Perucic AM, Fitzpatrick C. Tobacco use: Equity and social determinants. In: Blas E, Kurup AS, editors. Equity, social determinants and public health programs. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel V, Lund C, Hatherill S, Plagerson S, Corrigall J, Funk M, et al. Mental disorders: Equity and social determinants. In: Blas E, Kurup AS, editors. Equity, social determinants and public health programs. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. pp. 115–34. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt LA, Makela P, Rehm J, Room R. Alcohol: Equity and social determinants. In: Blas E, Kurup AS, editors. Equity, social determinants and public health programs. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deogaonkar M. Socio-economic inequality and its effect on healthcare delivery in India: Inequality and healthcare. [Last accessed on 2011 Oct 7]. Available from: http://www.sociology.org/content/vol8.1/deogaonkar.html .

- 25.Mendis S, Banerjee A. Cardiovascular diseases: Equity, social determinants. In: Blas E, Kurup AS, editors. Equity, social determinants and public health programs. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. pp. 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ministry of Human Resource development. Mid-Day Meal. [Last accessed on accessed on 2011 Oct 7]. Available from: http://education.nic.in/Elementary/mdm/index.htm .

- 27.Ministry of Rural Development. The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act. [Last accessed on 2011 Oct 7]. Available from: http://nrega.nic.in/netnrega/home.aspx .

- 28.World Health Organization. WHO: 2008-2013 action plan for the global strategy for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases: prevent and control cardiovascular diseases, cancers, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes. [Last accessed on 2011 Aug 24]. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241597418_eng.pdf .

- 29.Alleyne G. The multi-sectoral aspects of noncommunicable diseases. In: Ledger J, Pearson M, editors. Commonwealth Health Minister's update 2011. United Kingdom: Pro book Publishing Limited; 2011. pp. 52–44. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puska P, Vartiainen E, Tuomilehto J, Nissinen A. 20-year experience with the North Karelia Project, Preventive activities yield results. Nord Med. 1994;109:54–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim MK. Quest for quality care and patient safety: The case of Singapore. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:71–5. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2002.004994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goh LG, Chua T, Kang V, Kwong KH, Lim WY, Low LP, et al. Ministry of health clinical practice guidelines: Screening of cardiovascular disease and risk factors. Singapore Med J. 2011;52:220–5. quiz 226-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Red Ribbon Express project: Project Implementation Plan. New Delhi: NACO; 2007. National AIDS Control Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Bangkok Charter for Health Promotion in a Globalized World. Thailand: World Health Organization; 2005. World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nutbeam D. Health promotion glossary. Health Promot. 1998;1:113–27. doi: 10.1093/heapro/1.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shah P, Misra A, Gupta N, Hazra DK, Gupta R, Seth P, et al. Improvement in nutrition-related knowledge and behavior of urban Asian Indian school children: findings from the ‘Medical education for children/Adolescents for Realistic prevention of obesity and diabetes and for healthy ageing’ (MARG) intervention study. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:427–36. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510000681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reddy KS, Arora M, Perry CL, Nair B, Kohli A, Lytle LA, et al. Tobacco and alcohol use outcomes of a school based intervention in New Delhi. Am J Health Behav. 2002;26:173–81. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.26.3.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perry CL, Stigler MH, Arora M, Reddy KS. Preventing tobacco use among young people in India: Project MYTRI. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:899–906. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.145433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]