Abstract

Aims and Objectives:

To estimate serum vitamin B12 levels in type 1 diabetes and to evaluate the influence of duration of diabetes, diabetic control, and age on B 12 levels.

Importance of Study:

Vitamin B12 deficiency is known to be associated with autoimmune disorders. However, currently there is very limited and controversial data regarding the prevalence of B12 deficiency in type 1 diabetes in South Indian population. If our study demonstrates the presence of low serum B12 levels in type1 diabetes in our population, a recommendation for regular screening and supplementation of vitamin B12 could be considered in these patients.

Materials and Methods:

This was a cross- sectional study. Ninety type 1 diabetic patients (44 males and 46 females) were randomly selected based on inclusion/ exclusion criteria from the diabetes registry at Bangalore Diabetes Centre. Serum vitamin B12 level and parameters for diabetic controls were estimated using fully automated methods. All statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 16.

Results:

The study showed that 45.5% of the diabetics had low B12 using the manufacturer's cut – off of 180 pg/mL and 54% had low B12 using the published cut – off of 148 pmol/l (200pg/mL). There was no significant difference in B12 levels between males and females (mean difference = - 14.3: P > 0.05). The study did not demonstrate any significant correlation between vitamin B12 levels and age, duration of diabetes, and diabetes control (the r values being – 0.18, - 0.11, and - 0.08 respectively and the P-value > 0.05).

Conclusion:

Results of our study shows the presence of low serum B12 levels in type 1 diabetics. These findings merits further research on a larger population to investigate into the cause of deficiency and the benefit of B12 supplementation in these patients.

Keywords: Vitamin B12 deficiency, type 1 diabetes, duration of diabetes, diabetic control

INTRODUCTION

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (IDDM) results from autoimmune destruction of insulin producing beta cells and is characterized by the presence of insulitis and beta cell auto antibodies. It is associated with other autoimmune endocrine disorders and auto antibodies leading to the development of autoimmune polyglandular syndrome.[1] Autoimmune gastritis and pernicious anemia are common autoimmune disorders, being present in up to 2% of the general population. In patients with type 1 diabetes, the prevalence is increased up to 3 to 5 fold.[2–4] Presence of parietal cell antibodies (PCA) and antibodies to intrinsic factor have been demonstrated in these patients.[5,6] These factors could contribute to the occurrence of B12 deficiency in these patients. In addition, the dietary habits which vary from one population to another could also contribute to the deficiency. Association of vitamin B12 deficiency in type 1 diabetic patients has been demonstrated in previous studies.[7,8] However, there is insufficient data regarding prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in the South Indian population. Hence this study was undertaken to evaluate serum B12 levels in type 1 diabetics in South Indian population attending a tertiary care hospital. If the study shows a considerable proportion of type 1 diabetics with low vitamin B12 levels in this population, then it would be worthwhile to consider regular screening and supplementation of vitamin B12.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a cross-sectional study of 90 type 1 diabetic patients attending the outpatient endocrinology department of St John's Medical College Hospital and Bangalore Diabetes Centre. The patients were selected by random sampling from the Bangalore Diabetes Registry of Type 1 diabetics using random number table. Patients who were strict vegetarians, with history of malabsorption syndromes, previous gastrectomy, patients on metformin therapy and drugs known to interfere with vitamin B12 absorption, such as phenytoin, dihydrofolate reductase inhibitors, etc. were excluded from the study. The sample size of 90 ensured a power of 80 and true population prevalence estimate between 25 and 35% with a precision of 5.0%. Vitamin B12 was estimated in those samples which were received by the laboratory for estimation of diabetic profile. All parameters including blood glucose were estimated by fully automated methods on Siemens Dimension series. Vitamin B12 was estimated by fully automated chemiluminiscence system, Access 2 from Beckman and Coulter, USA. The analytical sensitivity of the assay was 50pg/mL, with an analytical measurement range of 50-1500 pg/ml and a total assay imprecision of 12 % across the measurement range

The study was conducted after obtaining the institutional ethical committee clearance.

Operational definitions

Type 1 diabetes was diagnosed based on history, clinical evaluation and laboratory findings. The American Diabetes Association criteria were used for the diagnosis.[9]

Vitamin B12 levels were evaluated based on the manufacturer's recommendations as follows: normal range: 180 - 914 pg/mL (133 - 675 pmol/L), indeterminate range: 145 -180 pg/mL (107 - 133 pmol/L) and deficient range: < 145 pg/mL (107 pmol/L).

Vitamin B12 levels were also evaluated based on a published meta-analysis report which considers a value less than 148 pmol/L (200 pg/mL) as deficient.[10]

Internal validity

The parameters were calibrated using calibrators with traceability to certified reference materials. Internal quality control samples from Bio-Rad, USA, were run to monitor the precision and accuracy of the assay.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed using descriptive statistics such as mean and SD for continuous variables and number and percentage for categorical variables. A one- sample t-test was carried out for the quantitative estimation of B12. Comparison between the groups was carried out by analysis of variance (ANOVA). Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to analyze the correlation between variables. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 15.

RESULTS

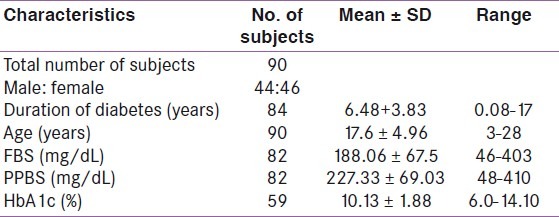

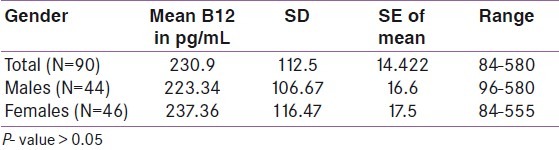

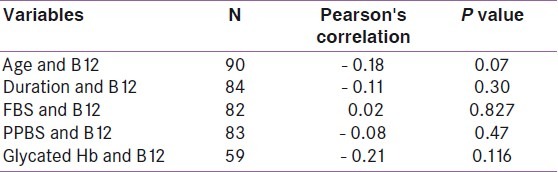

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study population. A total of 90 patients were included in the study. There was nearly equal representation of males and females in the study. The average age of patients was 17.6 years, while the average duration of diabetes was 6.48 years. The mean fasting blood sugar (FBS) was 188.06 mg/dL, while the post-prandial blood sugar (PPBS) was 227.33mg/dL and the glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was 10.13%. Using the manufacturer's cut- off, the prevalence of low serum vitamin B12 was found to be 45.50% with 95% confidence interval (CI) of 17.07 and 58.04% and a P- value of <0.05. Out of this, 28.5% had values in the deficient range while 17% were in the indeterminate range. The remaining 55.5% had values within the normal range. However when serum B12 levels were analyzed based on the published cut- off of 148 pmol/L (200 pg/mL), 54% had low values. Table 2 shows the comparison of vitamin B12 levels in males and females. There was no significant difference in B12 deficiency between males (mean B12 = 223.34pg/mL, SD = 106.67) and females (mean = 237.36pg/mL, SD = 116.47). Table 3 shows the correlation between vitamin B12 levels and age, duration of diabetes and diabetic control. There was also no correlation between B12 and the duration of diabetes (r = - 0.11), diabetic control (r values for FBS, PPBS, and HbA1c were 0.02, - 0.08 and - 0.21, respectively) or age (r = - 0.18).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

Table 2.

Comparison of vitamin B12 levels in the males and females

Table 3.

Correlation of vitamin B12 levels with different variables

DISCUSSION

Type 1 diabetes is frequently treated by primary care physicians who must be able to manage both the disease and its multiple co- morbidities. Vitamin B12 deficiency is a potential co- morbidity that is often overlooked, despite the fact that many diabetic patients are at risk for this specific disorder. For example, many diabetic patients are treated with metformin, a medication that lowers serum vitamin B12 levels and is associated with vitamin B12 deficiency.[11–14] In addition, symptoms of B12 deficiency occur late. B12 deficiency induced nerve damage may be confused with or may contribute to diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Identifying the correct etiology of neuropathy is crucial because simple vitamin B12 replacement may reverse the neurologic symptoms inappropriately attributed to hyperglycemia.[15] Studies on the western population have demonstrated the presence of vitamin B12 deficiency.[7–9] in type 1 diabetes. There are limited studies on the B12 levels in type 1 diabetics in the South Indian population. Therefore, defining the prevalence of low serum B12 levels in the diabetic population may help determine whether primary care physicians should consider screening for vitamin B12 levels in diabetic patients and carry out further evaluation with other metabolic markers such as methylmalonic acid (MMA) and holotranscobalamin.

Our study showed that the prevalence of low serum B12 in type 1 diabetics was dependent on the cut - off used: 45.50% using laboratory cut- off value and 54% using published cut- off of 148pmol/L. The difference in the prevalence of low B12 levels due to different cut- off values used has been reported in many studies in the past.[10] In addition, the lack of a gold standard complicates the diagnostic evaluations. Since serum B12 assays and other biomarkers such as MMA and holotranscobalamin lack sufficient sensitivity and specificity when used alone, a combination of markers along with clinical evaluation is preferred to define the prevalence of cobalamin deficiency. However markers such as MMA are expensive and not readily available in all laboratories. Hence serum cobalamin estimation continues to be used to assess the cobalamin status.[10] The mean B12 value obtained in our study was very low (230pg/mL), however, consistent with other reports, the deficiency was similar in males and females.[7,8,15,16] Gender bias was ruled out since there was equal representation of males and females in the study. Correlation analysis did not show any correlation between B12 and age, duration of diabetes, or diabetic control.

Vitamin B12 deficiency is estimated to affect 10 -15% of people over the age of 60, and the laboratory diagnosis is usually based on low serum vitamin B12 levels or elevated serum MMA and homocysteine.[17] The average age of our patients was 17 years, and therefore age cannot be considered as a risk factor in our study. Thus, it appears that factors other than age, duration of diabetes, and diabetic control may play a role in B12 deficiency. Since our patients were not on metformin, the observed B12 deficiency cannot be attributed to the drugs. The sample consisted of patients from various regions of Karnataka registered with the Bangalore Diabetes Registry, who followed different dietary habits. A detailed dietary history was not available and hence the role of dietary deficiency needs to be addressed. Since the study did not evaluate the presence of PCA, the role of autoimmune antibodies cannot be ruled out.

Limitations of the study

Comparison with a control population was not carried out and the cross- sectional nature of our study limits us to describing a single population. Since it is a preliminary study, other markers such as MMA and holotranscobalamin were not evaluated. The assay results were not correlated with the signs and symptoms and so the clinical significance of low B12 levels in our patient group is unknown.

CONCLUSION

Our study demonstrated the presence of low serum B12 levels in type 1 diabetics. These findings merit further research on a larger population using additional markers to investigate into the cause of deficiency, the factors involved, and benefit of B12 supplementation in these patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was funded by the Research Society, St John's Medical College Hospital, as part of undergraduate research mentorship program. The authors would also like to thank the staff of Bangalore Diabetes Hospital for their support in patient selection and data collection.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Research Society, St John's Medical College Hospital, as part of undergraduate research mentorship program.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Van den Driessche A, Eenkhoorn V, Van Gaal L, De Block C. Type 1 diabetes and autoimmune polyglandular syndrome: a clinical review. Curr Diab Rep. 2009;9:423–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van den Driessche A, Eenkhoorn V, Van Gaal L, De Block C. Type 1 diabetes and autoimmune polyglandular syndrome: a clinical review. Neth J Med. 2000;7:376–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Block CE, De Leeuw IH, Bogers JJ, Pelckmans PA, Ieven MM, Van Marck EA, et al. Autoimmune gastropathy in type 1diabetic patients with parietal cell antibodies. Histological and clinical findings. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:82–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riley WJ, Toskes PP, Maclaren NK, Silverstein J. Predictive value of gastric parietal cell auto antibodies as a marker for gastric and hematologic abnormalities associated with insulin dependent diabetes. Diabetes. 1982;31:1051–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.31.12.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Block CE, De Leeuw IH, Van Gaal LF. High prevalence of manifestations of gastric autoimmunity in parietal cell antibody- positive type 1 (insulin- dependent) diabetic patients. The Belgian Diabetes Registry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:4062–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.11.6095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Block CE, De Leeuw IH, Van Gaal LF. Autoimmune Gastritis in Type 1 Diabetes: A Clinically Oriented Review. Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:363–71. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wotherspoon F, Laight DW, Shaw KM, Cummings MH. Homocysteine, endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress: Determinants of hyperhomocysteinaemia in type 1 diabetes. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis. 2003;3:334–40. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hulberg B, Agardh CD, Agardh E, Lovestam- Adrian M. poor metabolic control, early age at onset and marginal folate deficiency are associated with increasing levels of plasma homocysteine in insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, A five year follow up study. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1997;57:595–600. doi: 10.3109/00365519709055282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Diabetes Association. Clinical practice recommendations 1999. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(Suppl 1):S1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carmel R. Biomarkers of cobalamin (vitamin B12) status in the epidemiological setting: a critical overview of context, applications and performance characteristics of cobalamin, MMA and holotranscobalamin II. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:348S–58. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.013441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hermann LS, Nilsson B, Wettre S. Vitamin B12 status of patients treated with metformin: a cross-sectional cohort study. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis. 2004;4:401–4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filioussi K, Bonovas S, Katsaros T. Should we screen diabetic patients using biguanides for megaloblastic anaemia? Aust Fam Physician. 2003;32:383–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pongchaidecha M, Srikusalanukul V, Chattananon A, Tanjariyaporn S. Effect of metformin on plasma homocysteine, vitamin B12 and folic acid: a cross - sectional study in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004;87:780–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeFronzo RA, Goodman AM. Efficacy of metformin in patients with non- insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:541–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508313330902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bell DS. Nondiabetic neuropathy in a patient with diabetes. Endocr Pract. 1995;1:393–4. doi: 10.4158/EP.1.6.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giannattasio A, Calevo MG, Minniti G, Gianotti D, Cotellessa M, Napoli F, et al. Folic acid, vitamin B12, and homocysteine levels during fasting and after methionine load in patients with Type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Endocrinol Invest. 2010;33:297–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03346589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baik HW, Russell RM. Vitamin B12 deficiency in the elderly. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999;19:357–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]