Abstract

Background:

Cardiovascular disease risk factors have a tendency to cluster. The presence of such a cluster in an individual has been designated the metabolic syndrome (MetS). There is a paucity of reports of the prevalence of MetS in hypertensive patients in south east Nigeria. This study was undertaken to determine the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome (MetS) among newly diagnosed hypertensive patients using the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP III) criteria in a tertiary healthcare centre in South East Nigeria.

Materials and Methods:

A population of 250 consecutive newly diagnosed adult hypertensive patients (126 males and 124 females) was evaluated. Blood pressure and anthropometric measurements were done using standardized techniques. After an overnight fast, blood samples were taken for glucose and lipid profile assays. The NCEP ATP III criteria were then applied for the diagnosis of MetS.

Results:

The prevalence of the MetS among the study population was 31.2%. The sex-specific prevalences were 15.1% and 47.6% among male and female patients respectively. A large number of the patients (40.4%) were at a high potential risk of developing the MetS as they already met 2 of the criteria. The MetS prevalence increased progressively from 14.3% through 23.8%, in the patients aged 24-33years and 34-43 years, respectively to a peak (40.4%) among those aged 44-53 years before declining in those aged 54-63 years (31.8%), 64-73 years (33.3%) and 74 years and above (20.6%). Central obesity was the most common component of the MetS being present in 50.4% of patients (28.6% of males and 72.6% of females). Of the other components, low HDL-C was present in 38.8% (26.2% of males and 51.6% of females), elevated FBS in 12.8% (6.3% of males and 19.4% of females) and elevated triglycerides in 8.8% (11.9% of males and 5.6% of females).

Conclusion:

The prevalence of the MetS is high among newly diagnosed hypertensive patients in Nnewi South East Nigeria. This underscores the importance of routine screening of hypertensive patients for other cardiovascular disease risk factors.

Keywords: Hypertension, metabolic syndrome, Nnewi, prevalence

INTRODUCTION

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a cluster of multiple metabolic abnormalities that increases the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.[1,2] The cluster includes various combinations of elevated blood pressure (BP), atherogenic dyslipidemia, obesity, abnormal glucose tolerance and insulin resistance (IR)[2] as well as such other abnormalities as pro-inflammatory and prothrombotic states.[3] The presence of the MetS is associated with an approximate doubling of the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality.[4,5] Similarly, in those without diabetes, the risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is increased 5-fold in the presence of MetS.[3] The central abnormality for the MetS is central obesity, which in itself increases the risk of IR.[6]

Hypertension is an important CVD risk factor with high global prevalence.[7] It is one of the most commonly identified components of the MetS.[8,9] When hypertension and other metabolic risk factors co-exist in an individual, they potentiate one another leading to a synergism that increases the total CVD risk well above that which results from the sum of the individual risk factors.[10] Recognition of this fact has led to a reorientation with regard to risk stratification and management of hypertension. Accordingly, many current guidelines on hypertension diagnosis and management emphasize that total CVD risk should be quantified so that the type and intensity of treatment can be tailored to the degree of overall risk rather than the level of BP elevation alone.[11,12] This approach maximizes the cost-effectiveness of hypertension management. The starting point of this therapeutic approach is the search for, and identification of, the various CVD risk factors in any individual presenting with any one of them. The NCEP-ATP III criteria for the diagnosis of the MetS were used in this study because of the ease of application in our environment when compared with most other criteria. The prevalence of MetS has become documented in Nigeria in some recent studies with rates varying from 12.1% to 54.3%,[13–17] but none came from Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital Nnewi.

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of MetS among patients with newly-diagnosed hypertension seen at the Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital (NAUTH) Nnewi. NAUTH is a tertiary hospital serving all the towns of Anambra, parts of Imo, Delta and Enugu States.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted at the medical and general out-patient clinics of Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital (NAUTH) Nnewi, Anambra state, South East Nigeria. Patients seen at these clinics are aged 16 years and above. A total of 250 consecutive newly diagnosed hypertensive patients were recruited.

Clinical evaluation

Clinical evaluation was done on the first day of subjects’ presentation to the medical or general outpatient clinic. The BP was measured in each arm using standard adult arm cuff of a mercury-type sphygmomanometer (Accoson, England) with the subject's arm supported and at least 10 minutes after rest in the sitting position. The measurement was repeated after 2 minutes. The average of the two measurements obtained in each arm was taken as the subject's blood pressure.[18] Where there was a difference in the BP between the two arms, the higher value was adopted.

Measurement of height was done to the nearest 0.01 metres using a stadiometer with the subject unshod, feet together, arms by the sides and in an erect posture on the stadiometer foot-rest. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.5 Kg using a weight scale with the subject wearing only light clothing.

Waist circumference (WC) was measured in a horizontal plane midway between the inferior margin of the ribs and the superior border of the iliac crest with the subject standing erect, arms by the sides but away from the trunk, abdomen bare and breathing normally. A non-stretchable tape measure graduated in centimeters was used for the measurement. The plane of the tape was parallel to the floor and the tape was fitted snugly, but did not compress the skin. The measurements were recorded to the nearest 0.5 cm as taken at the end of normal inspiration.

Laboratory evaluation

Blood samples for laboratory investigations were taken during subjects’ second visit because of the requirement for fasting. Thus subjects were instructed to carry out an overnight (i.e. 9-12 hours) fast on the night preceding their second visit. This instruction was given on their first day of presentation to the clinic. All laboratory tests were done in the Chemical Pathology laboratory of NAUTH, Nnewi.

Twelve milliliters (12 mls) of venous blood was drawn from a vein in the antecubital fossa of each subject after an overnight fast; 2mls for fasting blood sugar was placed in a fluoride oxalate bottle and centrifuged at 100 revolutions per minute for 5 minutes. The supernatant (plasma) was then separated into the appropriate container for analysis (sugar estimation). The remaining 10 mls of blood for lipid estimation was placed in a sterile plain container. It was allowed to clot over 30 minutes, the serum separated and used for lipid estimation. The samples were analyzed within 24 hours of collection or stored in a deep freezer at a temperature of about -10°C and analyzed within 2 weeks of collection.

Fasting blood glucose was determined by the glucose oxidase method described by Trinder;[19] serum triglycerides, total cholesterol, and HDL-C were determined using enzymatic colorimetric methods described by Searcy.[20] Allain et al,[21] and Burstein and Mortin[22] respectively. The reagents were supplied in commercial test kits.

Definitions

Hypertension was defined as systolic BP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg[18]

The diagnosis of the MetS was based on the NCEP-ATP III working definition.[2] Using this definition, subjects were regarded as having MetS if they had any three or more of the following conditions:

High BP defined as systolic BP greater than or equal to 130 mmHg and diastolic BP greater than or equal to 85 mmHg.

High fasting blood glucose defined as fasting blood glucose greater than or equal to 110 mg/dL (6.1 mmol/L)

Low HDL-C defined as plasma HDL-C less than 40 mg/dL (1.03 mmol/L) for males and less than 50 mg/dL (1.3 mmol/L) for females.

Abdominal obesity defined as WC greater than 102 cm (40 inches) in males and greater than 88 cm (35 inches) in females.

Hypertriglyceridemia defined as fasting plasma triglycerides greater than or equal to 150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L) for both males and females.

Data analysis

Data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Simple descriptive statistics was used to present the demographic characteristics. The student t-tests were used to compare continuous variables, and Chi-square (χ2) tests were used to compare categorical variables. Other associations were evaluated with Spearman's correlation coefficient.

A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital Ethical Committee (NAUTHEC).

RESULTS

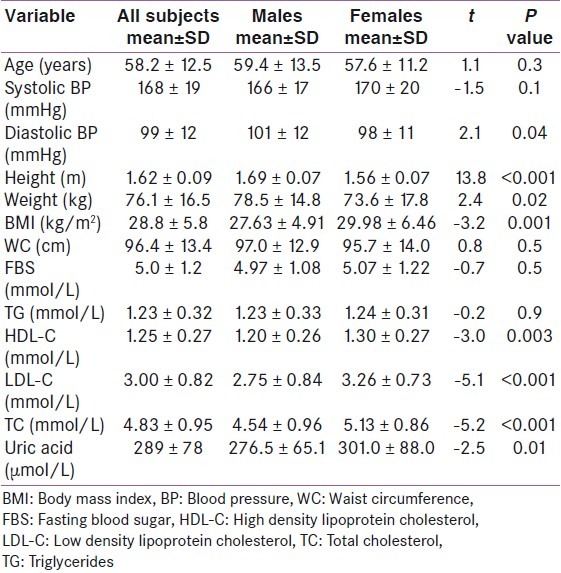

Out of the 250 newly diagnosed hypertensive adult subjects, there were 126 males and 124 females (ratio 1.02:1). The mean age of the subjects was 58.2 ± 12.5 years, with males being older than females (59.4 ± 13.5 years and 57.6 ± 11.2 years respectively), though the difference in age was not statistically significant (P = 0.3). The mean values of various anthropometric, clinical and biochemical variables measured are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mean values of anthropometric, clinical and biochemical variables in the subjects

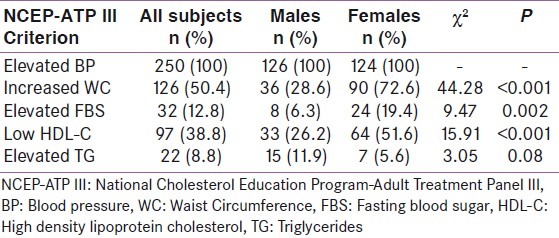

The prevalence of the five parameters for diagnosing MetS according to the NCEP-ATP III criteria is illustrated in Table 2. Central obesity showed the highest prevalence being present in more than half (50.4%) of all the subjects, followed by low HDL-C which was seen in more than a third (38.8%) of the subjects. Abnormally elevated FBS was present in 12.8% of participants. Each of these three parameters was significantly more prevalent among females than males (P <0.001, <0.001, <0.002 respectively). Elevated TG, which was the least prevalent of the 5 parameters (present in 8.8% of the subjects), however, showed a higher prevalence in males than females (11.9% and 5.6% respectively) though the difference lacked statistical significance P =0.08. All the subjects were hypertensive hence they all met the criterion of elevated blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg.

Table 2.

Prevalence of the different components of the MetS among the subjects

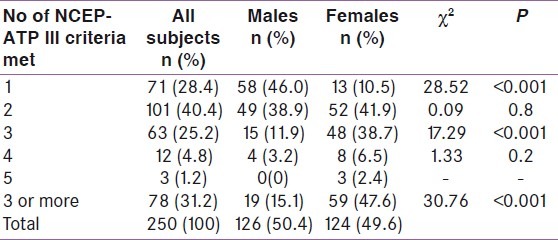

Table 3 shows that 31.2% of the newly diagnosed hypertensive adult subjects studied met the NCEP-ATP III criteria for the diagnosis of MetS, with a more than 3-fold higher prevalence among females than males (23.6% vs. 7.6%). Also a large proportion of the subjects (40.4%) were at a high potential risk of developing the MetS since they already met 2 of the NCEP-ATP III criteria.

Table 3.

Number of NCEP-ATP III criteria met by participants

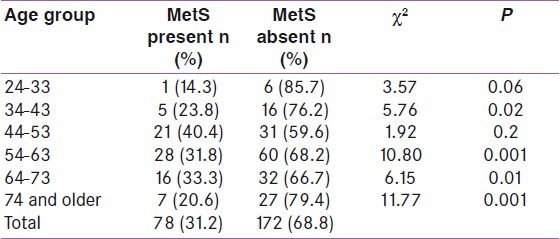

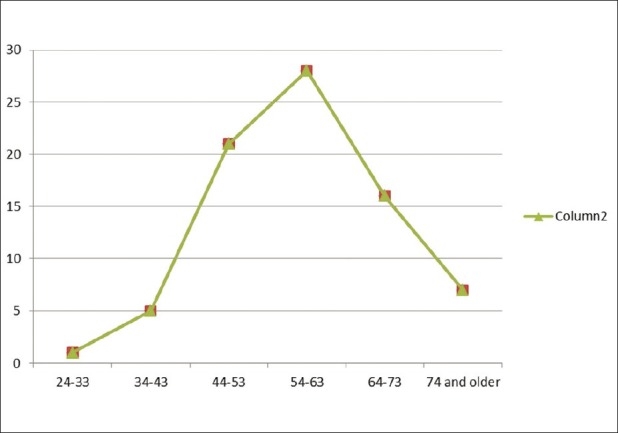

The relationship between the prevalence of MetS and age is shown in Table 4 and Figure 1. The prevalence increased progressively from the youngest age group up to a peak in the 54-63 years age group before declining slightly in those aged 64-73 years, and declined even further in those aged 74 years and above. There was thus a non-linear increase in MetS rate with increasing age, though this association was not statistically significant (χ2 =5.4, P =0.4

Table 4.

Metabolic syndrome and age

Figure 1.

Frequency of metabolic syndrome in various age groups

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of MetS was high among the newly diagnosed hypertensive subjects (31.2%), which is consistent with previous reports from earlier studies in Nigeria[23] and other parts of the world.[24–28] The high prevalence may imply that individuals with hypertension tend to have more clustering of other metabolic abnormalities than the general population.

The prevalence in the index study is comparable to the 34.7% reported by Ulasi et al,[23] among hypertensive subjects in a semi-urban population in Enugu, South East Nigeria.[23] Though they used the IDF criteria in their study, the closeness of the findings by Ulasi et al, to those of the present study may reflect the probable similarity in the characteristics of their hypertensive cohorts with those in the present study. This is so because Enugu and Nnewi are near each other and their inhabitants have many socio-demographic and other characteristics in common as both belong to the South-East zone of Nigeria occupied by Igbo speaking people.

The much higher rates of MetS among diabetic Nigerians as reported by Adediran et al,[16] in Sagamu, South west Nigeria (25.2%) and Isezuo[17] in Sokoto, North west Nigeria (54.3%), suggest that the clustering of CVD risk factors tends to be more frequent among diabetic than hypertensive patients. This observation is in keeping with reported strong association between the MetS and T2DM (MetS is associated with a 5-fold increase in the risk of developing T2DM)[1,3] which partly explains the classification of T2DM as a CVD risk equivalent by the NCEP-ATP III.[2]

In Kuwait, a rate of 34% was reported among hypertensive patients in a primary care clinic by Sorkhou et al,[26] while prevalence rates of 30.2% and 37% were reported by Cuspidi et al,[27] and Mule et al,[28] respectively among untreated hypertensive patients. It is possible that the close similarity in the findings in these studies with that of the present study reflect the near-identical methodological approaches - the use of NCEP-ATP III criteria and patients with newly diagnosed hypertension. However, much higher MetS rates were reported by Barrios et al,[29] in Spain, Ford et al,[30] in the United States and Yasein et al,[31] in Jordan (52%, 62.9%, and 52% respectively). The higher prevalence of MetS in these studies may be partly accounted for by the fact that they were conducted in more affluent countries where the prevalence of obesity (which is the main driving force for the MetS) is higher, and the diets more atherogenic.[32,33] Racial factors may also partly account for the difference in prevalence. For example Saad et al,[34] in a study to investigate the relationship between BP and IR among various ethnic groups reported a positive relationship among Caucasians but not among Blacks or Pima Indians. In addition, Black Africans are known to have lower adipose tissue mass for the same BMI than Caucasians.[35] The finding of significantly higher prevalence of MetS among Caucasian and Hispanic men than in their Black counterparts, as well as among Hispanic women than in their Black counterparts in the Third United States National Health and Nutrition Evaluation Study (NHANES III), seem to suggest that ethnicity may be important in determining the rate of MetS.[30]

The prevalence of MetS was more than three times higher in females than males (23.6% and 7.6% respectively) in the present study. This finding is consistent with the reported pattern of MetS prevalence in the general population in Nigeria.[23] Several other studies reported a higher prevalence in females than in males.[24,26,31,36] A few studies however reported equal prevalence between the genders[30,37] or even a male preponderance[38–40] which may probably be due to differences in methodology. In the NHANES III, the overall difference in prevalence between males and females was small (24% vs. 23.4%). However, among the African-Americans, who belong to the same racial group as the cohort in the present study, the prevalence was 50% higher in females (20.9%) than in males (13.9%).[30] The gender difference in prevalence of MetS may be due to the higher prevalence of obesity in females than in males and also the relatively sedentary lifestyle of women, in this part of the world, due in part to cultural and social barriers. More importantly rapid urbanization and acquisition of western life style have resulted in decreased physical activity and increased calorie intake.

Central obesity was the most common component of the MetS among the participants in the present study (50.4%). The identification of obesity as the most frequent component of the MetS had previously been reported by Ulasi et al,[23] among the hypertensive cohort in their study population. A similar finding had been reported in several other African studies.[36,41] Fezeu et al,[41] in Cameroon reported that central obesity was more highly associated with components of the MetS than was homeostasis model assessment for IR (HOMA-IR), and went further to conclude that central obesity was likely to be the key determinant of the prevalence of MetS in sub-Saharan Africa.

The prevalence of MetS has been reported in numerous studies to increase progressively with increasing age.[30,42,43] In the present study, the prevalence increased progressively from the youngest age group up to a peak in the 54-63 years age group before declining slightly in those aged 64-73 years and declining even further in those aged 74 years and above. Ulasi et al,[23] reported a similar pattern in nearby Enugu, while Kelliny et al,[36] reported a similar finding among their male subjects only. The reason for this may be due to the fact that advancing age affects all levels of pathogenesis which likely explains why the prevalence of MetS rises with advancing age. For example aging is associated with evolution of insulin resistance, other hormonal alterations, and increases in visceral adipose tissue[44] all of which are important in the pathogenesis of the MetS.

The age-related loss of body fat has been adduced as a possible reason for the decline in MetS rate among the oldest groups.[23] Again it is possible that individuals with multiple metabolic risk factors suffer increased CVD mortality relatively early in life so that fewer of them survive to reach old age, thus partly explaining the lower prevalence of MetS in the oldest age groups.

CONCLUSION

Our study showed a high prevalence of MetS among newly diagnosed hypertensive subjects. In view of this there is the need to screen all hypertensive patients for the other abnormalities that constitute the syndrome at the time of diagnosis. This will form a firm basis to prescribe lifestyle measures with or without pharmacologic therapy that will address these abnormalities holistically. More studies would be necessary to elucidate the extent of CVD risk associated with the diagnosis of the MetS in Nigerians and Blacks in general.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Reaven GM. Banting Lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37:1595–607. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.12.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Executive summary: The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cornier M, Dabelea D, Hernandez TL, Lindstrom RC, Steig AJ, Stob NR, et al. The metabolic syndrome. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:777–822. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. American Heart Association; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gami AS, Witt BJ, Howard DE, Erwin PJ, Gami LA, Somers VK, et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of incident cardiovascular events and death: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:403–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ, Shaw J The IDF Epidemiology Task Force Consensus Group. The metabolic syndrome - a new worldwide definition. Lancet. 2005;366:1059–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67402-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolf-Maier K, Cooper RS, Banegas JR, Giampolis S, Hense HW, Joffres M, et al. Hypertension prevalence and blood pressure levels in 6 European countries, Canada, and the United States. JAMA. 2003;289:2363–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meigs JB, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Wilson PW, Cupples LA, Nathan DM, Singer DE, et al. Risk variable clustering in the insulin resistance syndrome.The Framingham Offspring Study. Diabetes. 1997;46:1594–600. doi: 10.2337/diacare.46.10.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Working Group Report on Primary Prevention of Hypertension: National High Blood Pressure Education Program, Bethesda, Md: National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute document number 93-2669. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kannel WB. Risk stratification in hypertension: new insights from the Framingham study. Am J Hypertens. 2000;13:S3–10. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(99)00252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guidelines Committee. 2003 European Society of Hypertension-European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1011–53. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200306000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization/International Society of Hypertension Writing Group 2003. WHO/ISH statement on management of hypertension. J Hypertens. 2000;21:1983–92. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200311000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adegoke AO, Adedoyin RA, Balogun MO, Adebayo RA, Bisiriyu LA, Salawu AA. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in a rural community in Nigeria. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2010;8:59–62. doi: 10.1089/met.2009.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siminialayi M, Emem-Chioma PC, Odia OJ. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in urban and suburban Rivers State, Nigeria: International Diabetes Federation and Adult Treatment Panel III definitions. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2010;17:147–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sani MU, Wahab KW, Yusuf BO, Gbadamosi M, Johnson OV, Gbadamosi A. Modifiable cardiovascular risk factors among apparently healthy adult Nigerian population- a cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:11. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alebiosu CO, Odusan BO, Familoni OB, Jaiyesimi AE. Cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetic Nigerians with clinical diabetic nephropathy. Cardiovasc J S Afr. 2004;15:124–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isezuo SA. Is high density lipoprotein cholesterol useful in diagnosis of metabolic syndrome in native Africans with type 2 diabetes? Ethn Dis. 2005;15:6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lemogoum D, Seedat YK, Mabadeje AF, Mendis S, Bovet P, Onwubere B, et al. The International forum for hypertension control and prevention in Africa (IFHA) Recommendations for prevention, diagnosis and management of hypertension and cardiovascular risk factors in sub Saharan Africa. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1993–2000. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200311000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trinder P. Determination of blood glucose using 4-Aminophenazone as oxygen carrier Acceptor. J Clin Pathol. 1969;22:246. doi: 10.1136/jcp.22.2.246-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Searcy RL. Diagnostic Biochemistry. New York: McGraw Hill; 1961. Quantitative determination of triglycerides by enzymatic end-point. colorimetric method. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allain GC, Poon LS, Chan CS, Richmond W, Fu PC. Quantitative determination of cholesterol using enzymatic colorimetric method. Clin Chem. 1974;20:470–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burstein M, Mortin R. Quantitative determination of HDL-cholesterol using the enzymatic colorimetric method. Life Sci. 1969;8:345–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ulasi II, Ijoma CK, Onodugo OD. A community-based study of hypertension and cardio-metabolic syndrome in semi-urban and rural communities in Nigeria. [Last accessed on 2011 Aug 25];BMC Health Ser Res. 2010 10:71. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-71. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/10/71 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelishadi R, Derakhshan R, Sabet B, Saraf-Zadegan N, Kahbazi M, Sadri GH, et al. The metabolic syndrome in hypertensive and normotensive subjects: The Isfahan Healthy Heart Programme. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2005;34:243–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li WJ, Xue H, Sun K, Song XD, Wang YB, Zhen YS, et al. Cardiovascular risk and prevalence of metabolic syndrome by differing criteria. Chin Med J (Engl) 2008;121:1532–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sorkhou EI, Al-Qallaf B, Al-Namash HA, Ben-Nakhi A, Al-Batish MM, Habiba SA, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among hypertensive patients attending a primary care clinic in Kuwait. Med Princ Pract. 2004;13:39–42. doi: 10.1159/000074050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cuspidi C, Meani S, Fusi V, Severgnini B, Valerio C, Catini E, et al. Metabolic syndrome and target organ damage in untreated essential hypertensives. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1991–8. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200410000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mule G, Nardi E, Cottone S, Cusimano P, Volpe V, Piazza G, et al. Influence of metabolic syndrome on hypertension-related target organ damage. J Intern Med. 2005;257:503–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barrios V, Escobar C, Calderon A, Listerri JL, Alegria E, Muniz J, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with hypertension treated in general practice in Spain: An assessment of blood pressure and low density lipoprotein cholesterol control and accuracy of diagnosis. J Cardiometab Syndr. 2007;2:9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-4564.2007.06313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults. Findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2002;287:356–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yasein N, Ahmad M, Matrook F, Nasir L, Froelicher ES. Metabolic syndrome in patients with hypertension attending a family practice clinic in Jordan. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16:375–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grundy SM. Metabolic syndrome pandemic. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:629–36. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.151092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Misra A, Khurana L. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:S9–30. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saad MF, Lillioja S, Nyomba BL, Castillo C, Ferrara R, De Gregorio M, et al. Racial differences in the relation between blood pressure and insulin resistance. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:733–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103143241105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deurenberg P, Yap M, van Staveren WA. Body mass index and percent body fat: A meta-analysis among different ethnic groups. Int J Obes Rel Metab Disord. 1998;22:1164–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelliny C, William J, Riesen W, Paccaud F, Bovet P. Metabolic syndrome according to different definitions in a rapidly developing country of the African region. [Last accessed on 2011 Aug 25];Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2008 7:27. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-7-27. Available from: http://www.cardiab.com/content/7/1/27 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alegria E, Cordero A, Laclautra M, Grima A, Leon M, Cassanovas JA, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in the Spanish working population: MESYAS Registry. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2005;58:797–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohta Y, Tsuchihashi T, Arakawa K, Onaka U, Ueno M. Prevalence and lifestyle characteristics of hypertensive patients with metabolic syndrome followed at an outpatient clinic in Fukuoka, Japan. Hypertens Res. 2007;30:1077–82. doi: 10.1291/hypres.30.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Badr HE, Al Orifan FH, Amasha MM, Khadadah KE, Younis HH, Se’adah MA. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among healthy Kuwaiti adults: Primary health care centers based study. Middle East J Family Med. 2007;5:30–6. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abu Siddique MA, Sultan MA, Haque KM, Zaman MM, Ahmed CM, Rahim MA, et al. Clustering of metabolic factors among the patients with essential hypertension. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 2008;34:71–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fezeu L, Balkau B, Kengne A, Sobngwi E, Mbanya J. Metabolic syndrome in a sub-Saharan African setting: Central obesity may be the key determinant. Atherosclerosis. 2007;193:70–6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morimoto A, Nishimura R, Suzuki N, Matsudaira T, Taki K, Tsujino D, et al. Low prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its components in rural Japan. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2008;216:69–75. doi: 10.1620/tjem.216.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yi Z, Jing J, Xiu-ying L, Hongxia X, Jianjun Y, Yuhong Z. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among rural original adults in NingXia, China. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:140–5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boden G, Chen X, DeSantis RA, Kendrick Z. Effects of age and body fat on insulin resistance in healthy men. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:728–33. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.5.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]