Abstract

Efforts to address the current fragmented US health care structure, including controversial federal reform, cannot succeed without a reinvigoration of community-centered health systems. A blueprint for systematic implementation of community services exists in the 1967 Folsom Report—calling for “communities of solution.” We propose an updated vision of the Folsom Report for integrated and effective services, incorporating the principles of community-oriented primary care. The 21st century primary care physician must be a true public health professional, forming partnerships and assisting data sharing with community organizations to facilitate healthy changes. Current policy reform efforts should build upon Folsom Report’s goal of transforming personal and population health.

Keywords: public health, primary care, health care systems

INTRODUCTION

The current fragmented1 US health care sector provides lower quality care than most industrialized nations and at a higher cost.2–4 Efforts to address this low value, including the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, cannot succeed without a reinvigoration of a primary-care–based, community-centered health system.5–9 The Affordable Care Act provides multiple provisions for supporting a patient-centered medical system, improving training and enhancing reimbursement of the primary care workforce, and enabling community involvement. With an increasingly fragmented health system at every level, however, what is lacking is a policy blueprint for systematic implementation of integrated, community health services that meet the unique needs of every community. Such a guiding document exists: the 1967 Folsom Report.10 Revival and modernization of Folsom and his commission’s vision at this crucial time can help guide reform efforts and maximize health information technology’s potential to improve the health of Americans.

The Folsom Report was developed by the private National Commission on Community Health Services and sponsored by the American Public Health Association and the National Health Council. From 1963 to 1966, Chairman Marion Folsom (the prior treasurer of Eastman Kodak and US Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare) enlisted the 33-person commission to propose provision of more comprehensive health care, improvement in housing and transportation, as well as enhancement of urban and rural life—issues that resonate clearly today. The 252-page Folsom Report released in 1967 provided a wide-ranging set of recommendations to address 14 critical areas of concern.

The first recommendation of the report was that “the planning, organization, and delivery of community health services by both official and voluntary agencies must be based on the concept of a ‘community of solution.’” The Folsom Report emphasized that a community’s problem-sheds, much like the complex contributors to a watershed, bear little relation to its political, municipal, or jurisdictional boundaries. The Community of Solution concept arose from the recognition that complex political and administrative structures often hinder problem solving by creating barriers to communication and compromise. The boundaries of each community should be established by “the boundaries within which a problem can be defined, dealt with, and solved.”

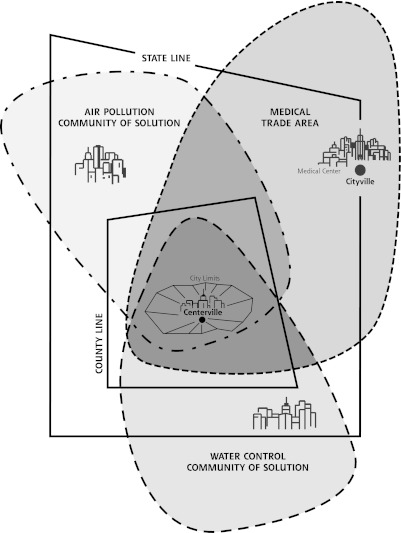

Figure 1 illustrates the Community of Solution notion as described in the Folsom Report, emphasizing the overlap of differently defined communities that can all affect an individual’s health. Embedded in the concept of the Community of Solution is the inherent difficulty in defining “community.” Perhaps the best description is from Dr Nutting’s seminal book on community-oriented primary care: “Community can be understood from three different perspectives, as territory or space, as group membership, or as a set of social structures and organization.”11 It is notable that even the Community Engagement Committee of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) cannot reach consensus on the proper definition of community. This ambiguity is the essence of community as used in the Folsom Report and is illustrated by Figure 1—communities are organically derived, highly variable, and matched to a particular need or needs.

Figure 1.

One city’s communities of solution.

Note: Political boundaries, shown in solid lines, often bear little relation to a community’s problem-sheds or its medical trade area.

Reproduced and adapted with permission from: Folsom M. Health is a Community Affair: Report of the National Commission on Community Health Service. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1967:3, Fig 1.

Folsom Report Legacies

The Folsom Report set a broad, ambitious vision for organizing health services to fit the needs of a 1960s society undergoing rapid change and increasing compartmentalization of care. Based on the organization of community health services distinct from political jurisdiction, the Folsom Report advocated that every individual have a personal physician as the central integration point for every patient’s medical services; it further recommended coordination of environmental health, mental health, health education, land and water management, as well as accident prevention. The report addressed manpower shortages, volunteer action, and community-level action planning. The vision of the Folsom Report was temporally concordant with social justice movements of the 1960s and 1970s,12 a not-for-profit health care system,13 and the World Health Organization’s Declaration of Alma-Ata in 1978 stressing the importance of an affordable community-based primary health care system.14

Folsom Report recommendations that were implemented include the development of community health centers and the National Health Service Corps,15,16 as well as the establishment in 1969 of the new medical specialty of family practice (later changed to family medicine.)17 The community-oriented primary care (COPC) movement also grew naturally under the direction of the Folsom Report, with the guiding principle:

Health is not a commodity that can be given. It must be generated from within. Similarly, health action cannot and should not be an effort imposed from outside and foreign to the people; rather it must be a response of the community to the problems that the people in the community perceive, carried out in a way that is acceptable to them and properly supported by an adequate infrastructure.18

But the Folsom Report did not anticipate for-profit health care.

THE PRESENT: OPPOSING FORCES OF COMMUNITY HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE AS A COMMODITY

What happened in the last 40 years? Health care became a commodity. Paul Starr famously observed, “The dream of reason did not take power into account.”19 The dream of community health currently is subservient to the power of the industry of health care. The US health care system is now a stunningly successful mechanism of wealth generation, with predictable downstream effects. Money flows toward sickness care and profits. The delivery of US health care has, with only a few notable exceptions, become more specialty-centric and separated from the community, antithetical to the Folsom Report’s precepts.1 Fragmentation of the health care system and discordant information technology systems impede the delivery of “comprehensive services,”20 with data used for proprietary interest. An environment of specialization (influenced by medical school admission policies and reimbursement differentials)21 overpowers primary care and the central role of the personal physician, making team-based and community-oriented care difficult to deliver. Although primary care practice and training redesign efforts are starting to shift the tide,22 most primary care training is still focused on the immediate individual patient, without including a broader community approach of public health. Antiquated fee-for-service physician payment schemes codify the individual focus and impede primary care physicians’ participation in broader community health activities.

Public health and medicine function largely independently of one another, “two cultures living in different and unfriendly worlds.”23 A century after the publication of the Flexner Report, in the opinion of the Association of American Medical Colleges, the Institute of Medicine, and many public health leaders,24,25 medical education in the United States is not training a health workforce capable of meeting the growing health inequities and chronic disease burden of the public. The Folsom Report’s call to unite public health and medicine in education, practice, and policy continues today from academic and political opinion leaders.26–29

Broad and flexible communities of solution currently are hindered by myriad factors: hospital systems, political boundaries that prevent collaboration, health care payment systems, special interests that carve out market niches, artificial separation of realms of public life, and disenfranchisement of community-based efforts. It is a time of opportunity to reinvest in the Community of Solution concept to enable the community itself to set its own health and public health agendas.

REINVIGORATION OF THE FOLSOM REPORT: WHY HOPE? WHY NOW?

The World Health Organization in 2010 succinctly stated the 5 key elements to achieving better health for all: (1) reducing exclusion and social disparities in health (universal coverage reforms); (2) organizing health services around people’s needs and expectations (service delivery reforms); (3) integrating health into all sectors (public policy reforms); (4) pursuing collaborative models of policy dialogue (leadership reforms); and (5) increasing stakeholder participation30—all echoes of the Folsom Report.

In the spring of 2010, the American Board of Family Medicine convened a working group of family physicians (the authors) to revisit and discuss the Folsom Report. The group embraced the buried wisdom of the report and continued discussions of its broader dissemination over subsequent months, ultimately leading to a modern version of the Folsom Report’s “grand challenges” for leaders in public health, communities, and medicine. These updated grand challenges were presented at a Robert Graham Center Primary Care Forum in Washington, DC, on October 5, 2010 (attended by an array of policy makers, opinion leaders, and students from federal agencies, think tanks, and academic institutions), and again at the North American Primary Care Research Group meeting November 2010 in Seattle, Washington. We were strongly encouraged to continue disseminating this updated vision for integrating community health services to inform health policy for a broader audience. Although we were initially dismayed by the lack of forward progress after publication of the original Folsom Report, we have since become rejuvenated by its continued wisdom, the COPC movement’s strong foundation, and current opportunities for (and evidence of) community-level change.

The Folsom Report was so far ahead of its time that forces were not aligned properly for implementation. Three factors are now in favor of a full modern implementation. First, it is evident that the current health care delivery system is economically unsustainable.31 We are getting sicker and spending more money, and communities are unhealthy. Abundant evidence shows that social determinants have more influence than medical care on health outcomes. The contribution of medical care to premature mortality (10%) is less important than social circumstances (15%), genetic predisposition (30%), and behavioral patterns (40%.)32 Public health spending, currently less than 5% of national health spending, is the strongest mutable determinant of community-level preventable mortality (increasing public health spending significantly decreases infant death and death from heart disease, diabetes, and cancer33). Constrained resources demand more effective allocation.

We also now have a primary care work force that is impatient for change. The Folsom Report, the Willard Report,34 and the Millis Commission35 recommended that every American “should have a personal physician who is the central point for integration and continuity of all medical and related services to the patient.” Between 1969 and 1975, 375 family medicine residency programs were established; today there are more than 83,000 living graduates of family medicine residency programs.12 Additionally, other primary care specialties (pediatrics, internal medicine, medicine-pediatrics) and nonphysician clinicians are interested in community-centric practice. Such innovations as the patient-centered medical home and direct practice models are the result of recognition by the Institute of Medicine and other agencies of the need for systems-based programs to assist primary care clinicians in implementing chronic care models, thus improving quality and reducing medical errors in a primary care–based health system.36,37

Finally, the explosion of health information technology (IT) and robustness of data platforms makes possible the full integration of primary care, mental health, public health, and community organizations. In the 1960s, Folsom and his commission could not have envisioned our current technological capabilities. Nutting’s 1987 COPC manual contained 1 chapter on computer-based systems, “COPC Applications for the Microcomputer”; it was a mere 4 pages long. Addressing social determinants requires linkage between public health, community health, mental health, and primary care; we now have powerful tools necessary to enable that linkage.

A CURRENT VIEW OF THE FOLSOM REPORT CHALLENGES

From the original 14 positions formulated in the Folsom Report, we have produced an updated series of 13 grand challenges to facilitate a vision for nationwide integrated patient-centered community health services. The renewal of the Community of Solution concept is the anchor point for improving overall health. The new grand challenges echo themes from recent health-related legislation, a reminder that the vision put forth by the Folsom Report remains relevant today. The original Folsom Report recommendations, the proposed grand challenges, and opportunities within recent legislation (including the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act [ARRA] of 2009), the Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act [CHIPRA] of 2009, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act [PPACA] of 2010) that align with the Grand Challenges are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Grand Challenges for Integrating Community Health Services

| Folsom Report Recommendations 1967 | Folsom Report at 50: Grand Challenges | Funded Provisions From ARRA, CHIPRA, and PPACA |

|---|---|---|

| A. Organization and delivery of community health services community of solution by relevant administrative area, not by political (city, county, state) jurisdictions | Grand challenge 1: Create a national network of community partnerships that engages and activates the citizenry to self-define communities of solution to develop and sustain community-tailored health programs at the local level aimed at matching local health needs with integrated health services | PPACA: Community-based Collaborative Care Network Program; National Prevention, Health Promotion and Public Health Council, chaired by the US Surgeon General, to coordinate federal prevention, wellness, and public health activities and to “elevate and coordinate prevention activities and design the focused National Prevention Strategy in conjunction with communities across the country to promote the nation’s health. The strategy will take a community health approach to prevention and well-being, identifying and prioritizing actions across government and between sectors”; Community Transformation Grants |

| B. Provision of high-quality comprehensive personal health services to all people in each community | Grand challenge 2: Foster the ongoing development of integrated, comprehensive care practices (patient-centered medical homes), accessible for all groups in a community, through the creation of explicit partnerships with public health professionals and communities of solution | ARRA: Increased funding for NIAMS CHCs, military hospitals, Veterans Administration, Indian reservations, NHSC, and COBRA subsidies CHIPRA: Coverage of additional 4.1 million children PPACA: Patient-centered medical home demonstration project within the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; Medicaid parity with Medicare; increased insurance access |

| C. Every individual should have a personal physician who is the central point for integration and continuity of all medical and related services to the patient | Grand challenge 3: Provide every individual in the United States the opportunity to form a partnership with a personal physician and a team of health professionals utilizing integrated community health services in communities of solution | ARRA: Funding for wellness and prevention CHIPRA: Funding for outreach, translation, interpretation; demonstrations to combat obesity PPACA: Preventive health care coverage mandate; $250 million Prevention and Public Health Fund to community programs (including the HRSA Healthy Weight Collaborative); interagency council headed by Surgeon General, focus on prevention and public health |

| D. Prospective planning and management of comprehensive environmental health services, includes water, air, food, hygienic housing, activity, and recreation | Grand challenge 4: Engage individuals in communities of solution in the creation of healthy environments, eliminating existing barriers to community-tailored strategies; endorse and implement a global conception of environmental health encompassing all physical, chemical, and biological factors external to a person that can potentially affect health | PPACA: Community Preventive Services Task Force |

| E. Ensure control of water and air pollution, biological and chemical product safety, radioactive material safety | ||

| F. Accident prevention: State health departments should develop accident prevention programs. US Public Health Service should establish a national accident prevention, research, training, service, and information facility analogous to the present Communicable Disease Center | Grand challenge 5: Engage communities of solution to recognize and address injuries as a main preventable source of global human death and disability, especially for children | |

| G. Family planning should be an integral part of community health services | Grand challenge 6: Sustain and improve family planning as an integral part of community health services | PPACA: State eligibility option for family planning services |

| H. Coordinate land use, transportation, economic development, and city planning to provide most effective and space use for urban populations | Grand challenge 7: Engage with community partnerships to coordinate with municipal authorities to design and build healthy living environments | PPACA: Community Preventive Services Task Force |

| I. Education for health: The community has a responsibility for developing an organized and continuing education concerning health resources for its residents; each individual has a personal responsibility for making full use of available health resources | Grand challenge 8: Enhance health literacy to empower individuals within communities of solution to be active participants in promoting their own health and the health of their communities | PPACA: Health care quality improvement programs; health care delivery system research; funding available for health literacy research |

| J. Health manpower: Effective utilization of available health personnel will reduce the current manpower shortage, and continuous evaluation of the use of manpower, accompanied by necessary changes and retraining, will provide additional manpower for existing new health services | Grand challenge 9: Create a health workforce to serve the needs of US communities, including community health workers | ARRA: NHSC expansion PPACA: Teaching Health Centers; Primary Care Extension Service; revisions to GME to favor nonhospital training; National Health Care Workforce Commission to align federal workforce resources with needs; preference of primary care for reallocation of unused GME slots |

| K. Hospital care: Further increases in hospital costs must not be accepted complacently; a wide range of vigorous and persistent actions must be taken by all parties concerned to moderate the costs of hospital care without adverse effects on quality | Grand challenge 10: Integrate health services—aligning hospital, ambulatory, and community care—across settings to promote quality and create value | PPACA: Establishment of accountable care organization pilot programs to comprehensively manage patient populations across settings |

| L. Every state should have a single, strong, well-financed, professionally staffed, official health agency with sufficient authority and funds to carry out its responsibilities and to assure every community of coverage by an official health agency and access to a complete range of community health services | Grand challenge 11: Transform the roles of the relevant federal, state, and local agencies by bridging public health and medicine to be effective partners in communities of solution | PPACA: Research on optimizing the delivery of public health services; Prevention and Public Health Fund Title IV, Prevention of Chronic Diseases and Improving Public Health |

| M. Voluntary citizen participation: A central factor in the growth and development of…personal and community health has been the participation of individuals and voluntary associations through dedicated leadership, financial support, and personal service | Grand challenge 12: Engage and support a citizen volunteer network formed by communities of solutions to educate, motivate, and collaborate for strategic local, regional, and national resource allocation informed by credible and actionable data | |

| N. Action planning for community health services: Planning is an action process and is basic to development and maintenance of quality community health services | Grand challenge 13: Utilize health information technology and emerging data-sharing innovative networks that enable the flow of relevant knowledge (public health, environmental, educational, legal, etc) to the communities of solution | ARRA: Beacon Community Cooperative Agreement Program PPACA: National Prevention, Health Promotion and Public Health Council; implementation of activities to improve patient safety and reduce medical errors through the appropriate use of best clinical practices, evidence-based medicine, and health information technology |

ARRA = American Recovery & Reinvestment Act of 2009; CHC = Community Health Center; CHIPRA = Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009; COBRA = Consolidation Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act; GME = graduate medical education; HRSA = Health Resurces and Services Administration; NIAMS=National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; NHSC = National Health Service Corp; PPACA = Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010.

Note: Grand challenges addressing each of the major recommendations from the Folsom Report10 and overlapping provisions from recent legislation.

The grand challenges serve as the guiding principles of an integrated action plan that, although ambitious and idealistic, is within reach if organizations and resources are harnessed in a coordinated way to bridge public health, clinical health leadership, and community-based agendas. Our hope is that these updated challenges will serve as a springboard for health care professionals, public health organizations, community groups, and policy makers to take concrete steps to reengage at the community level. Although each challenge is not discussed fully in the text, we are hopeful that readers will respond with their own ideas and initiatives and enable further discussion and action.

Implementation of the Modern Folsom Report Challenges: 3 Examples

Health Workforce Changes

Grand challenge 9 is the creation of a “health work-force to serve the needs of US communities, including community health workers.” Physicians make up an ever smaller proportion of the health workforce, and primary care clinicians, the backbone of health care, are lacking in many jurisdictions. In addition to increasing training and retention of primary care clinicians, a network of health care that extends into the community is necessary. The Folsom Report stressed “the need for another kind of professional health worker—the person capable of organizing and directing a community’s efforts to plan for its health service.” Although the primary care physician may be the cornerstone of the health provision team (and the doctor best able to assess health needs), the patient’s community should drive any agenda for health. The expanded chronic care model describes such a framework that supports productive interactions by uniting elements of population health promotion, prevention, social determinants of health, and community participation with health and medical systems teams.38

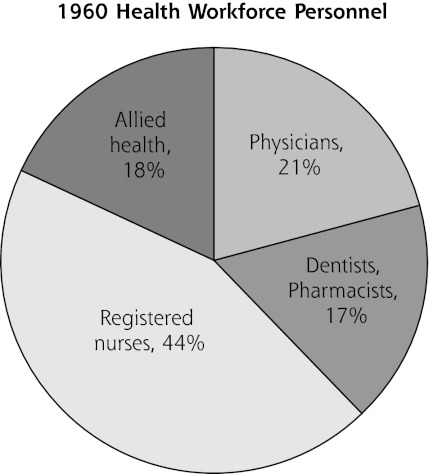

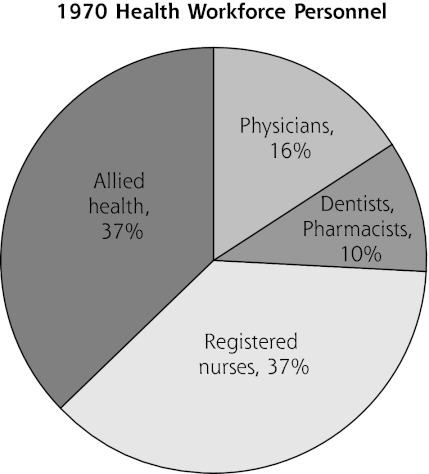

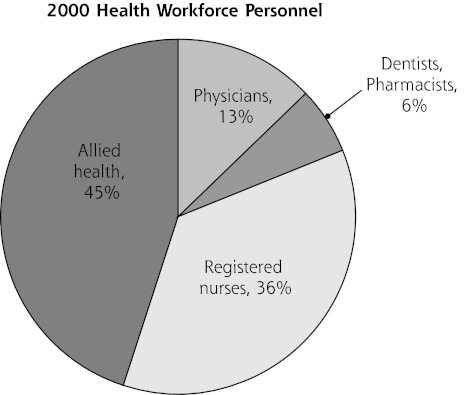

Health care workforce patterns in 1960, 1970, and 2010 (Figure 2) point to the need for more interprofessional collaboration and power sharing.

Figure 2.

Health workforce changes 1960 to 2000.

Note: Segments represent the proportion of the total health professional workforce, composed of allied health professionals (eg, dietitians, clinical laboratory workers, physical therapists, emergency medical technicians, etc); physicians (allopathic, osteopathic), dentists, and pharmacists; and registered nurses from 1960, 1970 and 2000. Sources of data: Health Resources & Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis (all except for allied health: http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/; allied health: http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/).

Community health outreach workers are a necessary addition to communicate the needs of the community to physicians and enable their community practice. An integrative work force policy (tasked to the newly formed National Healthcare Workforce Commission) should include a community-based work-force to enable the functioning of the Community of Solution, and each physician should consider the use of community health workers in his or her practice.

Community health workers are already being utilized more frequently, with positive results. The Community Health Foundation of Western and Central New York has trained community health workers to connect vulnerable individuals with resources.39 The Arkansas Community Connector Program, which similarly has connected vulnerable individuals with community-based services, and has shown a significant (23.8%) saving in health care expenditures.40 In the same manner, the Special Care Center in Atlantic City, New Jersey, uses health promoters extensively—community health workers who see their patients at least once every 2 weeks and come from the patients’ communities—to improve patient outcomes and decrease emergency utilization.41 In addition, coordination between practices and community-based organizations improved health outcomes (including injury prevention) of pediatrics patients in North Carolina.42

Example 2. Communities of Solution

In the original Folsom Report, 21 communities charged to identify and assess their local community health problems successfully set goals and developed plans of action. Current functioning communities of solution can offer practical and evidence-based lessons, as well as encouragement that the grand challenges (anchored on grand challenge 1) are within reach and economically viable. Community oversight is the essential to all Community of Solution programs, with local communities assuming the interest, capability, investment, and input into the endeavor.43 Although modern examples are mostly health-system (or health-insurer) driven and focus on health care utilization outcomes, ideally the Community of Solution would originate organically from any reference point (school, geographic area, or community connected by a need) and demonstrate a broad health outcome.

Vermont’s Blueprint for Health, begun in 2006, engages the community to improve health.44 Community health teams support medical homes and link primary care physicians with community-based interventions. This initiative currently serves 10% of Vermont’s population, and preliminarily has decreased hospital admissions, emergency utilization, and overall costs. Grand Junction, Colorado, illustrates other key strategic options.45 Factors in this Community of Solution include a payment system involving risk sharing; equal payment to physicians through private insurers, Medicaid, and Medicare; regionalization of services; “robust” end-of-life care; and a not-for-profit dominant payer source. Primary care physicians (in this case, mostly family doctors) are uniquely positioned as the initial entry into the health care system and the principal physicians tasked with coordination of care, supporting the interface between patients, all sources of care, and the community. Ascension Health (a nonprofit health system) has developed a community collaborative to improve the health of their patients. Notably, “executives in local health systems are expected to ‘step outside their hospital walls’ and work with other providers and safety-net organizations and programs.” 46

The expanded chronic care model also enables the Community of Solution. In the expanded chronic care model, “effective health promotion follows the lead of the community in addressing its needs and developing strategies to meet those needs.”38 This expanded model reflects many of the Folsom Report recommendations—including an integration of strategies to promote community wellness, emphasis on quality of life, utilization of community-wide data and information systems, generation of safe and achievable living and employment situations, and advocacy with and for vulnerable populations. The emergence of community engagement in health care delivery and research also provides a fresh and viable alternative to typical community outreach efforts.47,48

Example 3. Technological Opportunities

Perhaps the most exciting low-hanging opportunity is the potential to utilize technology to integrate individual-level, practice-level, and community-level health measures (grand challenge 13). Numerous emerging technologies and collaborations enable communities of solution in ways not imaginable in the 1970s. Community mapping (such as the Health Resources and Services Administration Uniform Data System mapping) links multiple data sources to reflect a community’s health. The public health information exchanges made possible with health (and nonhealth) information technology (IT) further facilitate comprehensive community-level health knowledge (such as school graduation rates, sidewalk miles, and grocery store locations). Such centers as the Indiana Center of Excellence in Public Health Informatics have as their express purpose the creation of “…one of the nation’s most technologically sophisticated, standards-based, comprehensive and longest-tenured health information exchanges combined with one of the nation’s leading spatially enabled community information systems. The long-term goal of our efforts is to improve the overall community health by informing and improving public health practice through innovative standards-based public health informatics initiatives.”46

Funding for IT linkage is in the early stages of growth. The Beacon Community Cooperative Agreement Program (ARRA, Division A-Title XIII, 2009) provides funding to selected communities to build and strengthen their health IT infrastructure and exchange capabilities. The program supports communities at the cutting edge of electronic health record adoption and health information exchange to push them to a new level of sustainable health care quality and efficiency.49 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality is also spearheading a national effort to build the infrastructure and utility of electronic clinical and community data.

PARALLEL TRANSFORMATION AND THE IMPORTANCE OF COMMUNITY-BASED SOLUTIONS

American health care is undergoing 2 related, yet often independent, transformations. First, federal health reform legislation acknowledges many of the broken elements of our health care industry and attempts to legislatively mandate changes and improvements (often by directing monetary flow toward desired outcomes). Many of these federal reform efforts are aligned with the vision of the Folsom commission and our contemporary grand challenges, but they are still powerfully linked to the industry of medicine and are subject to the political negotiation process.

The second type of reform is occurring locally in practices, communities, and public health programs throughout the United States. These local efforts are often independent of federal reform and also include a vision of binding together public health and primary care,50 developing and supporting communities of solution, and providing infrastructure and connection for a robust integrated health service.51 Regardless of the future of federal health care reform, the local reform efforts will continue and may find guidance in a fresh look at the Folsom commission’s goal of personalized care of each patient and their community, with integrated stakeholder leadership at every level.

The key lesson of the Folsom Report is that local decision making is of paramount importance. Communities governed by a local board of health show increased public health spending, likely because they can better identify funding targets.33 Ideally, federal health policy would more effectively enable local community-based reform efforts. For example, accountable care organizations, introduced in the Affordable Care Act as a pilot program within the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, are a potential modern-day Community of Solution, but are politically uncertain and too hospital-centric. Described currently as a group of physicians (possibly including a hospital) that is jointly responsible for the health care spending and outcomes of a particular patient population, accountable care organizations that were driven by community stakeholders could help direct health funding to the community’s health needs and enable collaboration for all those providing community health care.52

Similarly, the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Awards ideally would promote community-driven and -oriented research, but current funding mechanisms enable cash flow to academic centers and may hinder community-originated proposals. Research agendas should also include evaluation of Community of Solution approaches. As recommended by the Task Force on Community Preventive Services and others, evaluations of population-based Community of Solution interventions can and should be approached with the same level of rigor as the evidence-based practice and comparative effectiveness research of clinical interventions.53,54

THE MODERN PRIMARY CARE PHYSICIAN

The Folsom Report and COPC principles beautifully describe the ideal primary care physician. In fact, this vision continues to be vigorously promoted today. The modern primary care physician, who values “community participation, political involvement, and collective advocacy,”55 can, in effect, be a true public health professional, forming partnerships with community-based organizations that facilitate healthy change.56 This paradigm shift includes the transition from treating individuals in isolation to treating people in the context of their lives in their communities, indeed, culminating in community-centered care. “One of the first objectives for family physicians is to understand the living conditions patients face when they leave our office or when they leave the hospital,”57 that the biggest impact on health happens before and after the patient visit. The SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment, plan) note format applies equally well to community diagnosis, as described in the COPC manual “Individual-Community Problem Oriented Matrix.” 11 Primary care physicians need to be leaders in the modern Folsom movement by partnering with communities and advocating for adequate time and funding to participate in local communities of solution.

CONCLUSION

The vision of the Folsom commission could not be more pertinent to America’s current pressing needs. Defragmenting and improving the value of health care require a system that fosters non–health-care determinants of health.38,58,59 A strong and enabled Community of Solution improves the community. A strong community that, in turn, increases personal responsibility and produces good jobs, effective education, and safe housing will have the largest positive effect on the health of its residents and their ability to function as citizens and as a workforce.60–65

A commentary on the Folsom Report by Dr Willard66 highlights 2 conflicting value systems that continue to fight for ideological preeminence: the philosophy of social responsibility (society’s obligation to those who are underprivileged) and individual responsibility (the importance of personal initiative, free enterprise, and economic profit motive). The proposed synthesis of these 2 value systems is no less necessary today than in 1966, and it can be achieved through the locally powered Community of Solution. Here, efforts that are individualized, whole-patient centered, and community based, as well as integrated and multiprofessional, can succeed where systems that are individualistic, specialty, and medical care centered have not. We must work together to span boundaries created over time that now interfere with the Community of Solution approaches.

Systemic change is essential to promote and anchor person-centered care in a community environment. Such change may be more feasible now that health reform (and the current financial impracticality of health care) has again become a national priority. We propose communities of solution as a blueprint for improving population health and decreasing health costs. We call on all stakeholders to devise collaboratively and assess rigorously the impact on health outcomes of Community of Solution–based systems. As the lead author, Marion Folsom, asserted, “quality health services for all the people will require responsible action by individuals, by communities, and by health agencies serving in every dimension of public and private life.”10

As does the errant traveler returning to wise counsel once ignored, we revisit enduring lessons of the Folsom Report to inform a new generation of personal physicians, health care providers, policy makers, and citizens. We must define, embrace, serve, and actively partner with the community itself so we can transform personal and population health in the wake of once-in-a-generation health care reform.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the American Board of Family Medicine for organizational support of the Advisory Group, and the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care for health care workforce data acquisition. We are grateful for the accomplished assistance of Angela Henke from the Department of Family Medicine, University at Buffalo, State University of New York.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: the authors report none.

References

- 1.Stange KC. The problem of fragmentation and the need for integrative solutions. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(2):100–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sandy LG, Bodenheimer T, Pawlson LG, Starfield B. The political economy of U.S. primary care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(4):1136–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi L. The contribution of primary care systems to health outcomes within Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, 1970–1998. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(3):831–865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook J, Michener JL, Lyn M, Lobach D, Johnson F. Practice profile. Community collaboration to improve care and reduce health disparities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):956–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Task Force on Community Preventive Services. The community guide: what works to promote health: community guide branch. National Center for Health Marketing (NCHM) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. [Accessed Jun 30, 2009]. http://www.thecommunityguide.org. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM, Fisher ES. Primary care and accountable care—two essential elements of delivery-system reform. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(24):2301–2303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Weel C, De Maeseneer J, Roberts R. Integration of personal and community health care. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):871–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, Stange KC. Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(8):1489–1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NCCHS Health is a Community Affair—Report of the National Commission on Community Health Services (NCCHS). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1967 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nutting PA. Community-Oriented Primary Care: From Principal to Practice. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press; 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stephens GG. Remembering 40 years, plus or minus. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(Suppl 1):S5–S10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts DW. Health is a community affair. Preview of the final report of the National Commission on Community Health Services. JAMA. 1966;196(4):332–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan M. Return to Alma-Ata. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):865–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adashi EY, Geiger HJ, Fine MD. Health care reform and primary care—the growing importance of the community health center. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(22):2047–2050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenblatt RA, Andrilla CH, Curtin T, Hart LG. Shortages of medical personnel at community health centers: implications for planned expansion. JAMA. 2006;295(9):1042–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin JC, Avant RF, Bowman MA, et al. ; Future of Family Medicine Project Leadership Committee The Future of Family Medicine: a collaborative project of the family medicine community. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(Suppl 1):S3–S32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahler H. The meaning of “health for all” by the year 2000. World Health Forum. 1981;3(1):5–22 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Starr P. The social Transformation of American Medicine. Basic Books: New York, NY; 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 20.White KL. Two cheers for ecology. Ann Fam Med. 2003;1(2):67–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Council on Graduate Medical Education Council on Graduate Medical Education (COGME) Twentieth Report: Advancing Primary Care. Rockville, MD: Council on Graduate Medical Education; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green LA, Jones SM, Fetter G, Jr, Pugno PA. Preparing the personal physician for practice: changing family medicine residency training to enable new model practice. Acad Med. 2007;82(12):1220–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White K. Healing the Schism: Epidemiology, Medicine, and the Public’s Health. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gebbie K, Rosenstock L, Hernandez LM. Who Will Keep the Public Health Healthy? Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hernandez LM, Wezi Munthali A, eds. Training Physicians for Public Health Careers. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maeshiro R, Johnson I, Koo D, et al. Medical education for a healthier population: reflections on the Flexner Report from a public health perspective. Acad Med. 2010;85(2):211–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruis AR, Golden RN. The schism between medical and public health education: a historical perspective. Acad Med. 2008;83(12):1153–1157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berwick DM, Finkelstein JA. Preparing medical students for the continual improvement of health and health care: Abraham Flexner and the new “public interest”. Acad Med. 2010;85(9)(Suppl):S56–S65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jain SH, Cassel CK. Societal perceptions of physicians: knights, knaves, or pawns? JAMA. 2010;304(9):1009–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO Primary Health Care. Geneva, CH: World Health Organization; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keehan SP, Sisko AM, Truffer CJ, et al. National health spending projections through 2020: economic recovery and reform drive faster spending growth. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(8):1594–1605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schroeder SA. Shattuck Lecture. We can do better—improving the health of the American people. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(12):1221–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mays GP, Smith SA. Evidence links increases in public health spending to declines in preventable deaths. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(8):1585–1593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.AMA Meeting the Challenge of Family Practice. The Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Education for Family Practice of the Council of Medical Education. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association (AMA); 1966 [Google Scholar]

- 35.AMA The Graduate Education of Physicians. The report of the Citizens Commission on Graduate Medical Education. Chicago, IL: American Medical Education (AMA); 1966 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu WN, Bliss G, Bliss EB, Green LA. Practice profile. A direct primary care medical home: the Qliance experience. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):959–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.The Patient Centered Medical Home: History, Seven Core Features, Evidence and Transformational Change. Washington, DC: The Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barr VJ, Robinson S, Marin-Link B, et al. The expanded Chronic Care Model: an integration of concepts and strategies from population health promotion and the Chronic Care Model. Hosp Q. 2003;7(1):73–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grimm K, Walker J. Challenges & Opportunities of Community Health Workers in Buffalo, NY [white paper]. Buffalo, NY: Community Health Foundation of Western and Central New York; 2011. http://www.chfwcny.org/Tools/BroadCaster/Upload/Project234/Docs/Challenges_and_Opportunites_of_Community_Health_Workers_in_Buffalo__NY_4_15_11.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 40.Felix HC, Mays GP, Stewart MK, Cottoms N, Olson M. The Care Span: Medicaid savings resulted when community health workers matched those with needs to home and community care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(7):1366–1374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gawande A. The hot spotters: can we lower medical costs by giving the neediest patients better care? The New Yorker. January 24, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Margolis PA, Stevens R, Bordley WC, et al. From concept to application: the impact of a community-wide intervention to improve the delivery of preventive services to children. Pediatrics. 2001;108 (3):E42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferrer RL, Carrasco AV. Capability and clinical success. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(5):454–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bielaszka-DuVernay C. Vermont’s Blueprint for medical homes, community health teams, and better health at lower cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(3):383–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bodenheimer T, West D. Low-cost lessons from Grand Junction, Colorado. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(15):1391–1393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Felland LE, Ginsburg PB, Kishbauch GM. Improving health care access for low-income people: lessons from ascension health’s community collaboratives. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(7):1290–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Westfall JM, Mold J, Fagnan L. Practice-based research—“Blue Highways” on the NIH roadmap. JAMA. 2007;297(4):403–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.US Department of Health & Human Services Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. 2011. http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt/community/healthit_hhs_gov__home/1204 Accessed May 4, 2011

- 50.Institute of Medicine Integrating Primary Care and Public Health. http://www.iom.edu/Activities/PublicHealth/PrimaryCarePublicHealth.aspx Accessed May 4, 2011

- 51.Flynn G. Department of Health and Human Services National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics. The community as a learning system for health: using local data to improve community health. February 8, 2011. http://www.ncvhs.hhs.gov/110208p3.pdf

- 52.US Department of Health & Human Services Affordable Care Act to improve quality of care for people with Medicare. Proposal for Accountable Care Organizations will help better coordinate care, lower costs [press release]. March 31, 2011; http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2011pres/03/20110331a.html Accessed May 4, 2011

- 53.Kindig D, Mullahy J. Comparative effectiveness—of what?: evaluating strategies to improve population health. JAMA. 2010;304(8): 901–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lipsey MW. The challenges of interpreting research for use by practitioners: comments on the latest products from the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(2)(Suppl 1):1–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gruen RL, Campbell EG, Blumenthal D. Public roles of US physicians: community participation, political involvement, and collective advocacy. JAMA. 2006;296(20):2467–2475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shortell SM, Swartzberg J. The physician as public health professional in the 21st century. JAMA. 2008;300(24):2916–2918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Woolf S. 2011. National Conference. Family Physician Urges Residents, Students to Consider ‘Social Determinants’ of Health 2011; http://www.aafp.org/online/en/home/publications/news/news-now/health-of-the-public/20110803ntlconfwoolf.html Accessed Aug 29, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 58.World Health Organization Commission on Social Determinants of Health - Final Report. 2008. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/final_report/en/index.html Accessed Aug 13, 2010

- 59.Fielding JE. Economic and social determinants of prevention in health care provision in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 1988; 4(4)(Suppl):158–170, discussion 171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lavizzo-Mourey R, Williams DR. Strong medicine for a healthier America: introduction. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(1)(Suppl 1):S1–S3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Braveman PA, Egerter SA, Mockenhaupt RE. Broadening the focus: the need to address the social determinants of health. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(1)(Suppl 1):S4–S18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miller WD, Sadegh-Nobari T, Lillie-Blanton M. Healthy starts for all: policy prescriptions. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(1)(Suppl 1):S19–S37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Woolf SH, Dekker MM, Byrne FR, Miller WD. Citizen-centered health promotion: building collaborations to facilitate healthy living. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(1)(Suppl 1):S38–S47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miller WD, Pollack CE, Williams DR. Healthy homes and communities: putting the pieces together. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(1)(Suppl 1):S48–S57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Braveman PA, Egerter SA, Woolf SH, Marks JS. When do we know enough to recommend action on the social determinants of health? Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(1)(Suppl 1):S58–S66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Willard WR. Report of the National Commission on Community Health Services—next steps. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1966;56(11):1828–1836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]