Abstract

The East Pacific Rise (EPR) at 9°50'N hosts a hydrothermal vent field (Bio9) where the change in fluid chemistry is believed to have caused the demise of a tubeworm colony. We test this hypothesis and expand on it by providing a thermodynamic perspective in calculating free energies for a range of catabolic reactions from published compositional data. The energy calculations show that there was excess H2S in the fluids and that oxygen was the limiting reactant from 1991 to 1997. Energy levels are generally high, although they declined in that time span. In 1997, sulfide availability decreased substantially and H2S was the limiting reactant. Energy availability dropped by a factor of 10 to 20 from what it had been between 1991 and 1995. The perishing of the tubeworm colonies began in 1995 and coincided with the timing of energy decrease for sulfide oxidizers. In the same time interval, energy availability for iron oxidizers increased by a factor of 6 to 8, and, in 1997, there was 25 times more energy per transferred electron in iron oxidation than in sulfide oxidation. This change coincides with a massive spread of red staining (putative colonization by Fe-oxidizing bacteria) between 1995 and 1997.

For a different cluster of vents from the EPR 9°50'N area (Tube Worm Pillar), thermodynamic modeling is used to examine changes in subseafloor catabolic metabolism between 1992 and 2000. These reactions are deduced from deviations in diffuse fluid compositions from conservative behavior of redox-sensitive species. We show that hydrogen is significantly reduced relative to values expected from conservative mixing. While H2 concentrations of the hydrothermal endmember fluids were constant between 1992 and 1995, the affinities for hydrogenotrophic reactions in the diffuse fluids decreased by a factor of 15 and then remained constant between 1995 and 2000. Previously, these fluids have been shown to support subseafloor methanogenesis. Our calculation results corroborate these findings and indicate that the 1992-1995 period was one of active growth of hydrogenotrophic communities, while the system was more or less at steady state between 1995 and 2000.

Introduction

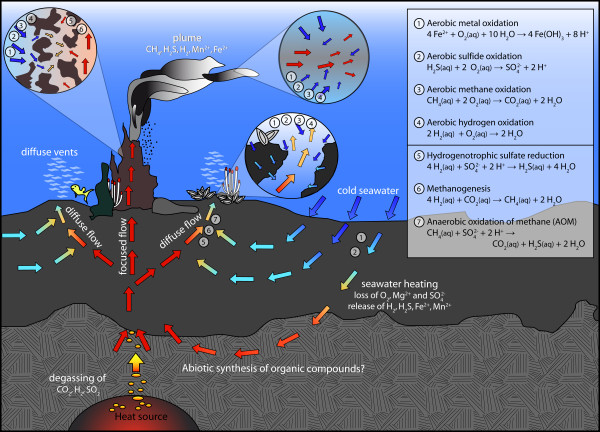

Microorganisms have the ability to gain energy for their metabolism by promoting a large range of redox reactions. Well-known energy sources are for example aerobic oxidation of methane or hydrogen sulfide, methanogenesis, fermentation, and sulfate reduction under anaerobic conditions [1]. In habitats like hydrothermal systems or mines, lacking sunlight and organic carbon sources, the primary production depends on electron donors that are released by water-rock reactions. High-temperature (> 400°C) processes of water-rock interaction determine the composition of seawater-derived hydrothermal fluids that are equilibrated with rocks at depths as much as several kilometers (Figure 1). Upon upwelling, these fluids cool (conductively and/or adiabatically) and mix with cold seawater to varying extents. High temperature fluids, venting focused via black smoker chimneys, often show little evidence for subseafloor mixing and are typically used as "hydrothermal endmember" compositions. Commonly, sites of diffuse venting are developed around the black smokers, and the temperature-composition relations of the fluids issuing through the seafloor there indicate that the diffuse fluids formed by subseafloor cooling and mixing of hot hydrothermal fluids with cold seawater. The seafloor underneath these diffuse vent sites is a particularly favorable environment for a variety of chemosynthetic microorganisms in terms of suitable temperature and large energy availability (Figure 1). The composition of the upwelling hydrothermal fluids in these diffuse vent sites imposes a major control on the metabolic diversity in the colonizing ecosystem. Because of this tight relation between vent ecosystem and fluid compositions, chemical changes in the fluid may directly influence the ecosystem.

Figure 1.

Sketch of idealized fluid flow within a hydrothermal system and potential catabolic reactions in different environments (chimney wall, plume, recharge zone, and subseafloor mixing zone). Upwelling hot, reducing hydrothermal fluids mix with entrained cold, oxygenated seawater in subseafloor mixing zones. For these zones, the affinities of the catabolic reactions provided in the inset are examined in this paper.

Thermodynamic calculations based on geochemical compositions of waters in these habitats provide insights into the energy availability and can determine possible reactions that can support primary production in these systems [2-5]. Tight relations between the availability of geochemical energy and microbial processes have been demonstrated for a variety of submarine hydrothermal environments, including chimney walls, diffuse fluids, and vent mussels [6-10].

In this study we use geochemical data from two hydrothermally active vents in the East Pacific Rise 9°50'N area to show that thermodynamic modeling can help interpret the microbial metabolism in such systems. For the first area, our calculations provide clues to the biological evolution of a vent site influenced by dynamic changes in fluid chemistry and, consequently, catabolic energy. The other case shows that microbial processes in the subseafloor may be deciphered by determining and comparing free energies of reactions for catabolic reactions of hypothetical fluids derived from conservative mixing of seawater and hydrothermal fluid with the diffuse fluid actually sampled.

Methods

Calculation of affinity

Free energy for catabolic reactions is available only if the system is out of geochemical equilibrium. Disequilibrium prevails when the properties of the system change at rates faster than the rates at which the thermodynamically favored reactions proceed. The abiotic rates of many redox reactions are sluggish, in particular at temperatures conducive of life (< 120°C)[5]. Microbes use enzymes to catalyze these redox reactions and harness the free energy by controlling electron transfers and converting a sizable fraction of the catabolic energy in ATP production for their anabolic metabolism [11]. The maximum quantity of free energy that microorganisms can catabolize (ΔrG) is given by the Gibbs energy at a reference state (ΔrG° = -RTlnKr) representing the intensive parameters (P, T) and an extensive term (RTlnQ) that captures the compositions of the vent solutions (equation 1):

where R is the universal gas constant and T the temperature in Kelvin. Kr is the calculated equilibrium for the temperature and pressure of interest, and Qr expresses the activities of species participating a specific reaction. Qr is evaluated through equation (2):

where ai represents the activity of the chemical species in the reaction, vir denotes the stoichiometric coefficient for the ith chemical species in the reaction, which is positive for products and negative for reactants. If ΔrG for a reaction is negative, then the reaction should proceed from left to right; if it is greater than zero, the reaction will proceed in the opposite direction. By convention a negative sign indicates that the reaction should take place spontaneously and energy can be gained by microbes catalyzing this reaction.

Commonly, affinity is used instead of ΔrG for a reaction [12]. Affinities express the change of the Gibbs energy with reaction progress (ξ) (equation 3):

It follows that the reaction is favorable if the affinity is positive. Combining equations 1 and 3, the affinity can be evaluated through equation (4):

This relation demonstrates that, if Kr > Qr, then Ar > 0 and the reaction may proceed while free energy is released [12].

Two types of computations were employed in this study: (1) calculation of concentrations and activities of dissolved species in diffuse fluids, and (2) calculation of affinities of potential catabolic reactions in these fluids. These calculations were conducted for actual diffuse fluids sampled and analyzed by Von Damm and Lilley [13] and for hypothetical mixtures of endmember vent fluids [14] and ambient seawater. It is assumed here that the diffuse fluids form by subseafloor mixing of ascending hydrothermal fluids with seawater. The endmember hydrothermal fluid composition is taken from black smoker vent fluids issuing within a few meters of the diffuse vent site [13,14]. The percentage of hydrothermal fluid is estimated using a simple mass balance for silica:

Silica is known to precipitate slowly at low temperatures from mildly acidic fluids [15] and can be assumed to behave conservatively at the time scales of fluid mixing [16].

Geochemist Workbench® (GWB) was used to conduct the thermodynamic calculations [17]. A Log Kr database was created, covering temperatures from 0 to 350°C at a pressure of 25 MPa, using SUPCRT92 [18] and the thermodynamic database OBIGT [19], and including all speciation reactions in an aqueous system with Na, Ca, Mg, Fe, Sr, K, SiO2, Cl, sulfate, sulfide, oxygen, hydrogen and carbon dioxide. Likewise, equilibrium constants for the following catabolic reactions were calculated.

Aerobic sulfide oxidation

| (1) |

Aerobic methane oxidation

| (2) |

Aerobic iron oxidation

| (3) |

Aerobic hydrogen oxidation

| (4) |

Hydrogenotrophic sulfate reduction

| (5) |

Hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis

| (6) |

Anaerobic oxidation of methane

| (7) |

Published compositions of endmember vent fluids [13,14] issuing from black smoker chimneys in proximity (few meters) to the diffuse vent site were used in the calculations of affinities for these reactions (Table 1). In determining Qr (equation2), the extended Debye-Hückel equation was used to calculate activity coefficients with extended parameters and hard core diameters for each species from Wolery and Jove-Colon [20]. Dissolved neutral species were assigned an activity coefficient of one, except non-polar species for which CO2 activity coefficients were used [21]. Reported pH values of hydrothermal vents (measured at 25°C) were used in determining the in situ pH (Table 1) by re-speciating the fluids at the temperatures of venting [22]. The percentage of hydrothermal endmember fluid in the diffuse fluids derived from the silica mass balance was used to calculate idealized mixed fluids, assuming conservative behavior of all elements. These hypothetical fluids were also speciated and compared with actual compositions of diffuse fluids in terms of concentrations and affinities (Tables 1 and 2). Deviations from conservative behavior in the diffuse fluids indicate that removal or release processes take place in the subseafloor mixing zones in which the diffuse fluids are formed. In the calculations, the activities of species in the hypothetical diffuse fluids (ideal conservative mixing) were determined in a batch mixing model simulating titration of hot hydrothermal endmember fluid into cold seawater and tracking the chemical speciation changes in the mixed fluid. In these calculations, redox reactions were suppressed, while kinetically fast reactions like protonation of bases, dissociation of acids, and complex formation are allowed to take place spontaneously. Redox reactions were suppressed, because these reactions are not expected to proceed at the low temperatures of the diffuse fluids and on the short time scales of the mixing process [23]. This procedure has the advantage that disequilibria formed during mixing can be determined and the affinities of selected redox reactions may be calculated. GWB also allows suppressing the Knallgas reaction, so elevated concentrations of both O2 and H2 in the mixed fluids could be accounted for [9].

Table 1.

Compositions of discrete and diffuse vent fluids

| Temperature (°C) | pH (25°C) (1) | in situ pH | Mg2+ mM | Na+ mM (1) | Cl+ mM | SiO2 (aq) mM | H2 (aq) μM | H2S (aq) mM | Fe2+ μM | CH4 (aq) μM | CO2 (aq) mM | O2 (aq) μM (5) | SO42- mM (1, 6) | % hydrothermal fluid (4) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seawater | 1.8 | 7.8 | 8.1 | 52.2 | 464 | 540 | 0.155 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.30 | 100 | 28.2 | 0 | |

| Northern Area | ||||||||||||||||

| April 1991 | hot endmember | 368 | 2.6 | 3.2 | 0 | 139 | 154 | 9.90 | 3030 | 23.2 | 2190 | 172 | 44.8 | - | 0 | 100 |

| diffuse, measured | 22 | - | - | 49.7 | - | 530 | 0.88 | 0.36 | 0.90 | 151 | 0.070 | 5.90 | - | - | 7.39 | |

| diffuse, calculated | 22 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 48.3 | 440 | 511 | 0.88 | 225 | 1.72 | 162 | 12.8 | 5.46 | 92.6 | 26.1 | 7.39 | |

| December 1993 | hot endmember | 365 | 3.6 | 5.7 | 0 | 188 | 212 | 11.3 | 700 | 7.30 | 1060 | 1000 | 204 | - | 0.18 | 100 |

| diffuse, measured | 30.9 | - | - | 49.6 | - | 522 | 0.57 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 24.2 | 5.80 | 9.57 | - | - | 3.68 | |

| diffuse, calculated | 30.9 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 50.3 | 454 | 528 | 0.57 | 25.9 | 0.27 | 39.3 | 37.1 | 9.77 | 96.3 | 27.2 | 3.68 | |

| March 1994 | hot endmember | 363 | 3.5 | 5.1 | 0 | 222 | 249 | 12.6 | 680 | 8.50 | 1430 | 112 | 187 | - | 0.035 | 100 |

| diffuse, measured | 29.9 | - | - | 50.4 | - | 525 | 0.79 | 1.90 | 0.27 | 25.0 | 6.58 | 9.57 | - | - | 5.06 | |

| diffuse, calculated | 29.9 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 49.6 | 452 | 525 | 0.79 | 34.5 | 431 | 72.5 | 5.68 | 11.7 | 94.9 | 26.8 | 5.06 | |

| October 1994 | hot endmember | 364 | 3.2 | 3.8 | 0 | 279 | 325 | 14.1 | 530 | 6.20 | 2730 | 86.0 | 146 | - | 1.55 | 100 |

| diffuse, measured | 32.3 | - | - | 48.1 | - | 524 | 0.92 | 6.79 | 0.11 | 69.9 | 4.83 | 8.54 | - | - | 5.45 | |

| diffuse, calculated | 32.3 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 49.3 | 454 | 528 | 0.92 | 29.2 | 0.34 | 150 | 4.74 | 10.2 | 94.5 | 26.7 | 5.45 | |

| November 1995 | hot endmember | 366 | 3.0 | 3.9 | 0 | 391 | 466 | 14.8 | 360 | 6.70 | 6030 | 84.0 | 139 | - | 0 | 100 |

| diffuse, measured | 33.3 | - | - | 46.3 | - | 550 | 1.14 | 2.50 | 0.19 | 277 | 5.37 | 9.01 | - | - | 6.69 | |

| diffuse, calculated | 33.3 | 5.4 | 5.3 | 48.7 | 459 | 535 | 1.14 | 24.2 | 0.45 | 406 | 5.65 | 11.5 | 93.3 | 26.3 | 6.69 | |

| November 1997 | hot endmember | 373 | 3.1 | 4.1 | 0 | 342 | 400 | 13.4 | 330 | 8.60 | 6640 | 95.0 | 117 | - | 0 | 100 |

| diffuse, measured | 27.2 | - | - | 50.5 | - | 534 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.003 | 170 | 2.52 | 4.70 | - | - | 4.23 | |

| diffuse, calculated | 27.2 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 50.0 | 459 | 534 | 0.72 | 14.1 | 0.37 | 284 | 4.07 | 7.21 | 95.7 | 27.0 | 4.23 | |

| Southern Area | ||||||||||||||||

| April 1991 | diffuse, measured | 55 | - | - | 46.7 | - | 504 | 1.95 | 2.17 | 8.46 | 2.40 | 505 | 10.1 | - | - | - |

| February-March | hot endmember | 160 | 3 (2) | 3.7 | 0 | 126 (3) | 136 | 12.7 | 6460 | 20.7 | 4080 | 213 | 31.0 | - | - | 100 |

| 1992 | diffuse, measured | 23.3 | - | - | 48.2 | - | 529 | 0.69 | 14.9 | 0.66 | 2.00 | 94.0 | 4.57 | - | - | 4.28 |

| diffuse, calculated | 23.3 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 50.0 | 479 | 523 | 0.69 | 277 | 0.89 | 175 | 9.12 | 3.53 | 95.7 | 27.0 | 4.28 | |

| December 1993 | diffuse, measured | 15.4 | - | - | 50.5 | - | 532 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.001 | 9.20 | 2.87 | 2.70 | - | - | - |

| March 1994 | hot endmember | 20.5 | - | - | 0 | - | 269 | 5.57 | 8910 | 11.2 | 200 | 748 | 118 | - | - | 100 |

| October 1994 | hot endmember | 351 | 3 (2) | 0 | 229 (3) | 235 | 12.5 | 8390 | 14.3 | 1590 | 116 | 104 | - | - | 100 | |

| diffuse, measured | 20.4 | - | - | 49.7 | - | 526 | 0.66 | 6.75 | 0.21 | 11.5 | 15.6 | 4.96 | - | - | 4.05 | |

| diffuse, calculated | 20.4 | - | 5.8 | 50.1 | 484 | 528 | 0.66 | 343 | 0.58 | 65.0 | 4.74 | 6.46 | 95.9 | 27.0 | 4.05 | |

| November 1995 | hot endmember | 341 | 3 (2) | 3.7 | 0 | 297 (3) | 301 | 13.8 | 4930 | 14.0 | 1550 | 106 | 95.7 | - | - | 100 |

| diffuse, measured | 24.7 | - | - | 50.3 | - | 531 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.53 | 9.90 | 15.9 | 5.80 | - | - | 5.06 | |

| diffuse, calculated | 24.7 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 49.5 | 484 | 528 | 0.85 | 250 | 0.71 | 78.7 | 5.38 | 7.04 | 94.9 | 26.8 | 5.06 | |

| November 1997 | hot endmember | 307 | 3 (2) | 3.4 | 0 | 326 (3) | 330 | 16.1 | 3550 | 11.3 | 742 | 121 | 81.9 | - | - | 100 |

| diffuse, measured | 18.2 | - | - | 51.5 | - | 530 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.24 | 27.0 | 4.09 | 3.84 | - | - | 2.57 | |

| diffuse, calculated | 18.2 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 50.9 | 490 | 535 | 0.57 | 91.3 | 0.29 | 19.1 | 3.11 | 4.35 | 97.4 | 27.5 | 2.57 | |

| April 2000 | hot endmember | 279 | 3 (2) | 3.3 | 0 | 355 (3) | 359 | 16.8 | 2700 | 11.2 | 517 | 108 | 77.0 | - | - | 100 |

| diffuse, measured | 11.9 | - | - | 50.4 | - | 529 | 0.23 | 0.15 | 0.055 | 23.0 | 0.47 | 2.57 | - | - | 0.42 | |

| diffuse, calculated | 11.9 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 52.0 | 494 | 539 | 0.23 | 12.5 | 0.051 | 2.39 | 0.50 | 2.65 | 99.5 | 28.1 | 0.42 | |

Fluid data for high temperature fluids and measured diffuse fluids are from Von Damm and Lilley, 2004 [13]

Northern Area: Hot vent fluids are from Bio9 and Bio9' and the associated diffuse fluids from BM9Rifia, BM91o and BM12

Southern Area: High temperature fluids are from Tube Worm Pillar (TWP) and the diffuse fluids from Y vent at the base of TWP

(1) pH, sodium and sulfate concentrations of vent fluids are from Von Damm [14], unless otherwise indicated

(2) pH was not measured but is approximated by comparison with similar vent fluids from Von Damm [14]

(3) Na+ calculated by charge balance

(4) Calculated assuming conservative behavior of SiO2(aq)

(5) O2(aq) in diffuse fluids was calculated from conservative mixing, assuming 100 μMol O2 for pacific bottom seawater [30]

(6) When sulfate concentrations are not reported, it is assumed to be zero in the endmember vent fluids

Table 2.

Affinities for different catabolic reactions in kJ and normalized affinities in J per e- and Kg Vent-fluid at the Southern Area (TWP)

| Southern Area | 5 Hydrogenotrophic sulfate reduction | 6 Hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis | 7 Anaerobe oxidation of methane | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured | Predicted | Measured | Predicted | Measured | Predicted | |

| kJ | kJ | kJ | ||||

| February-March 1992 | 128.6 | 156.7 | 94.1 | 128.0 | 34.5 | 28.7 |

| October 1994 | 129.3 | 165.1 | 93.4 | 135.3 | 35.9 | 29.8 |

| November 1995 | 104.3 | 161.2 | 70.1 | 130.8 | 34.2 | 30.4 |

| November 1997 | 103.9 | 151.1 | 73.8 | 122.5 | 30.1 | 28.7 |

| April 2000 | 88.4 | 130.4 | 63.9 | 105.7 | 24.7 | 24.5 |

| J per e- and Kg vent fluid | J per e- and Kg vent fluid | J per e- and Kg vent fluid | ||||

| February-March 1992 | 1.34 | 30.28 | 0.98 | 24.73 | 9.07 | 0.73 |

| October 1994 | 0.64 | 41.50 | 0.46 | 34.01 | 1.64 | 0.41 |

| November 1995 | 0.05 | 23.57 | 0.03 | 19.13 | 1.27 | 0.38 |

| November 1997 | 0.08 | 16.34 | 0.06 | 13.24 | 0.58 | 0.42 |

| April 2000 | 0.09 | 10.95 | 0.06 | 8.88 | 0.31 | 0.33 |

The precipitation of minerals was also suppressed. The thermodynamically stable Fe-minerals in the diffuse fluids are hematite and pyrite. If these phases were allowed to precipitate, Fe concentrations would drop to extremely low values in the hypothetical mixed fluids. The measured diffuse fluids have Fe concentrations that are many orders of magnitude higher than values corresponding to pyrite and hematite solubility. They are hence strongly oversaturated with respect to pyrite and hematite and indicate that precipitation of these minerals was largely inhibited. The concentrations of Fe and H2S calculated for the hypothetical mixed fluids represent maximum values.

The affinities calculated (Table 2) represent the maximum energy content for the different catabolic reactions, disregarding the fact that limiting electron donors and acceptors, which appear in several reactions, can still only be used once within the ecosystem [24]. Moreover, comparisons of the raw affinities do not reflect differences in the numbers of electrons transferred in these reactions. This is problematic, because a given quantity of proton motive force driving chemiosmosis is generated by a set number of electrons transferred. The fact that the reactions considered have between one and eight electron transferred therefore skews a comparison of the affinities of different reactions. We hence report the affinities in values per electron transferred (Table 2). Furthermore, the energy flux into the system is controlled by the concentration of the limiting reactant in the upwelling fluid. To examine these combined effects on energy availability, we normalized affinity to kg vent fluid by multiplying the energy with the concentration of the limited reactant, and divided by the fraction of endmember vent fluid in the mix [24]. These normalized affinities provide us with a meaningful parameter for assessing the fluxes of energy for different catabolic reactions into a system. While affinities expressed in both notations are reported in Table 2, the following discussion will primarily use normalized affinity, i.e., energy flux.

Results and Discussion

Case studies

The sample locations are situated in the axial summit caldera of the fast spreading (11 cm/yr full rate) ridge EPR at 9°50'N at a water depth of 2500 meters. In both case studies we use data from time series studies conducted in the 1990s. Venting temperatures are ≤55°C, and fluids issue from cracks in the seafloor or from lava pillars that are fissured near the base. Compositions of vent fluids from the two sites are reported in Von Damm and Lilley [13] and Von Damm [11]. These publications also present a detailed description of the geological setting and vent field characteristics, so we here highlight only the key features of these localities.

The northern area is characterized by the high temperature vents Bio9 and Bio9' and the associated diffuse flow sites BM9Riftia (BM9R), BM91o and BM12. The data set for this system (hereinafter referred to as Bio9 area) is the most detailed, because the site was the target of long-term measurements of fluid composition and temperature [25] and seismic activity [26]. Sohn et al. [26] documented a seismic swarm in 1995 in this area, followed by a temperature increase in the Bio9 vent with a delay of a few days [25]. Temperatures of the diffuse fluid samples range between 22.0 and 33.3°C (Table 1).

The southern area (Tube Worm Pillar, TWP) features high temperature venting through an 11-m high sulfide structure on top of a lava pillar. Discrete venting of 351°C fluid is restricted to the top of the chimney, while leakage of diffuse fluids is observed from around the base of the chimney. Eponymous for the site name, a large tubeworm colony inhabits the area of diffuse venting. The associated diffuse fluid samples were retrieved from Y vent, an adjacent broken-off lava pillar that issued fluids of temperatures between 20 and 25°C in 1992-1995, dropping to 18°C in 1997 and finally to 12°C in 2000.

Case study 1 - Bio9 area

Shank et al. [27] studied the change in the vent community during the time period from 1991 to 1995 at the vents in the Bio9 area. These authors report of a magmatic event in 1991, followed by venting of fluids high in hydrogen sulfide. These conditions boosted the establishment of a strong population of the tubeworm Riftia. During the following cruises in 1994, Shank et al. [27] observed the development of rusty spots that appeared within the Riftia colonies. In 1995, the rusty spots had spread and covered large areas of the Riftia population. In 1997, the Riftia population had broken down largely, while the rust had extended to cover much of the Riftia patch [13].

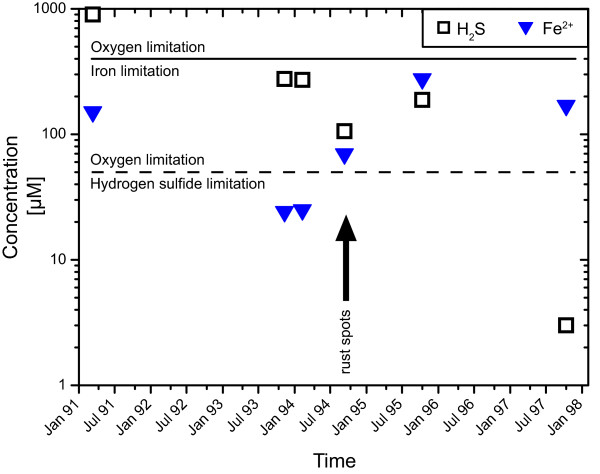

The temporal evolution of the fluid compositions in that time span reveals a decrease in hydrogen sulfide concentrations over the entire period after 1992 with a slight increase in November of 1995 (Figure 2). Before March of 1994, soluble iron follows the hydrogen sulfide concentration; afterwards the iron content increased and reached maximum concentrations during November of 1995. In November of 1997, the Fe concentration had dropped slightly, but was still much higher than during the beginning of the time series.

Figure 2.

Temporal changes in concentrations of dissolved iron and hydrogen sulfide in diffuse fluids from the Bio9 area. The increase in iron coincides with the appearance of rusty spots in the tubeworm colony (black arrow). The two horizontal lines represent the maximum concentrations of sulfide (dashed) and iron (continuous) that can be oxidized by seawater with an oxygen concentration of 100 μM. Iron is the limiting reactant over the whole time period, in contrast to sulfide, which is oxygen limited, except for the conditions in November 97.

It has been suggested that the biological development of this area depends on the bioavailability of iron and H2S [13]. This interpretation is plausible, because Riftia live in symbiosis with sulfide oxidizing bacteria [28] and depend on the energy associated with sulfide oxidation. Also, Fe-oxidizing bacteria oxidize Fe2+ in the fluids to ferric hydroxide [29]. So the "rust" in the study area is an indicator that these microorganisms are thriving.

We determined the affinities for both catabolic pathways for the time period of critical geochemical and ecological changes (1991-1997) to improve the understanding of the biological evolution of the vent ecosystems. The calculations make use of the measured concentrations of iron, H2S and oxygen. Unfortunately concentrations of oxygen and the pH for diffuse fluids are not available; therefore, these values are estimated from conservative mixing. Calculated pH values for the fluids show a narrow range of 5.3 to 5.7; likewise, small variations are predicted for oxygen concentrations (92 - 96 μM). Both pH and O2 concentrations reflect the large fraction of seawater calculated from the silica mass balance. Depending on the mixing ratio of vent fluid and seawater, either one of the electron donors (Fe2+, H2S) or oxygen is the limiting reactant determining the amount of energy available per unit vent fluid based (Figure 2). Figure 2 shows the upper limit for iron and H2S oxidation based on an oxygen concentration of the East Pacific bottom seawater of circa 100 μM oxygen [30]. For H2S oxidation, O2 is the limiting reactant, while Fe-oxidation is limited by the availability of iron. An exception is the fluid sampled last in the time series; it exhibits exceptionally low sulfide concentrations and H2S is the compound limiting energy availability.

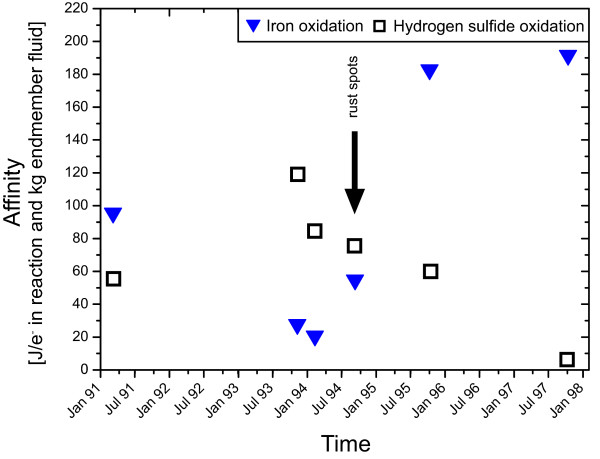

Figure 3 illustrates the normalized affinities for both reactions. It shows the consequence of limitation; sulfide oxidation has the highest affinity when the fraction of vent fluid in the mixture is lowest (Table 1), because then oxygen contents are greatest. In contrast, the normalized affinities for iron oxidation more closely mirror the iron concentration in the fluid. But affinities are also dependent on the vent fluid fraction, as increased pH favors ferric hydroxide precipitation from the mixed fluids.

Figure 3.

Normalized affinities for the oxidation of Fe2+ and H2S in diffuse fluids from the Bio9 area during the period from April 1991 until November 1997. The generally high affinities for iron and hydrogen sulfide oxidation support life catabolizing these reactions. In October of 1994, affinities for both reactions are high, so that tubeworms (H2S-oxidizers) and iron oxidizing microorganism (rusty staining) can grow simultaneously. The demise of the Riftia population in November of 1997 coincides with a sudden drop in the affinity of H2S oxidation.

The dynamic changes in the normalized affinities of sulfide and iron oxidation (Figure 3 and Additional File 1) can fully explain the ecological changes within the system. The incipient occurrence of rusty staining in November of 1994 correlates with an increased normalized affinity of iron oxidation, while the normalized affinity for sulfide oxidation remains at the same level. In November of 1995 a further increase in iron concentration in the fluid explains the continued spreading of the iron oxide staining. Tied to this change, the normalized affinity for Fe-oxidation almost quadrupled. The normalized affinity for hydrogen sulfide oxidation was only slightly decreased relative to 1994, which explains why the tubeworm colonies were still thriving, despite the increased development of rusty staining. Apparently, both metabolic pathways were favorable and were being exploited at that stage of system evolution. After 1995, the normalized affinity for hydrogen sulfide oxidation dropped as a consequence of the strongly decreased sulfide concentration in the fluid. Because of this drop in the affinity of sulfide oxidation, the tubeworm population, relying on favorable energetics for H2S oxidation, collapsed. Unlike sulfide oxidation, the normalized affinity for iron oxidation remains high, so organisms with the ability to gain energy from iron oxidation can still thrive. Since both reactions depend on oxygen, the reactions are in competition for that electron acceptor and the calculated affinities (Figure 3) are the predicted maxima.

The thermodynamic calculations presented here validate the interpretation by Von Damm and Lilley [13] and confirm that the ecological changes are driven by changes in fluid composition.

Case study 2 - Tube Worm Pillar (TWP)

The fluid compositions of the diffuse fluids issuing in TWP area have been proposed to reveal insights in the redox reactions in the subseafloor [13,31]. Increased methane concentrations in the diffuse fluids led Von Damm and Lilley [13] to propose that hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis takes place in the subseafloor. Proskurowski et al. [31] could confirm this interpretation through carbon stable isotope measurements of methane and CO2 demonstrating that the carbon isotope ratios are consistent with active microbial carbon cycling in this area.

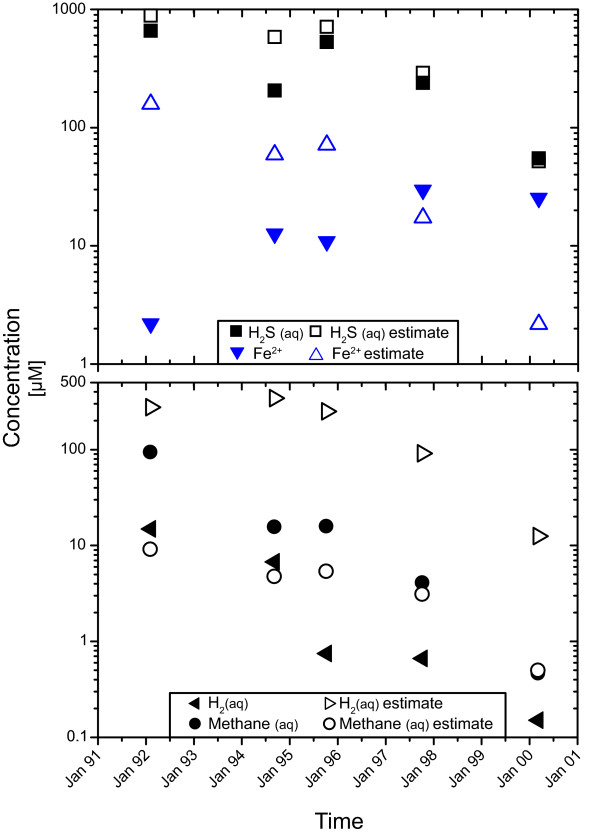

The compositional changes of diffuse fluid compositions relative to the concentrations predicted from conservative mixing are depicted in Figure 4. Throughout the time series, H2 concentrations are decreased by 1.5 to 2 orders of magnitude relative to the concentrations expected from conservative mixing (cf. Table 1). Methane, in contrast, is enriched by a factor of ten relative to the value predicted from conservative mixing in February-March of 1992. In October 1994 and November 1995 this enrichment is about 3-fold. By 2000, measured methane corresponds to those predicted from conservative mixing, and no methane excess can be observed (Figure 4). The methane excess in 1992-1995 is consistent with the decrease in hydrogen, and ratios of H2 depletion to CH4 excess between 3 and 6 are consistent with the stoichiometry of the hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis reaction, from which that ratio would be predicted to be 4. In 1997 and 2000, however, methane excess was minimal and H2 depletion was still significant, suggesting that other hydrogen-consuming reactions may have also played a role.

Figure 4.

Predicted and measured concentrations of iron, hydrogen sulfide, hydrogen, and methane for diffuse fluids in the Tube Worm Pillar area. Hydrogen is strongly depleted over the entire period. Methane is enriched in the diffuse fluids, which may show methanogenesis in the subseafloor [13]. Until 1997, iron and H2S concentrations are generally lower than predicted from conservative mixing. In November of 1997 predicted and measured concentration are similar to each other. In April of 2000 measured H2S concentrations also correspond to the predictions from conservative mixing, but Fe-concentrations are higher than predicted in the diffuse fluid. Loss of Fe2+ and H2S may be associated with precipitation of minerals. The surplus of measured Fe2+ in 2000 could indicate hydrogenotrophic iron reduction.

While methane enrichment and depletion of hydrogen are indicators for methanogenesis, some of the methane may be metabolized shallower in the system prior to venting by aerobic or anaerobic respiration (Figure 1). There are indications from the Guaymas Basin that anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) may take place in vent settings and at temperatures > 30°C [32]. Our calculations suggest that AOM is energetically feasible, so a loss of methane through AOM may be possible. If this reaction took place in the subseafloor, depletions of methane should be associated with increased hydrogen sulfide concentrations. This trend is not observed. AOM may still be taking place, but the rates are too small to affect the compositions of the diffuse fluids.

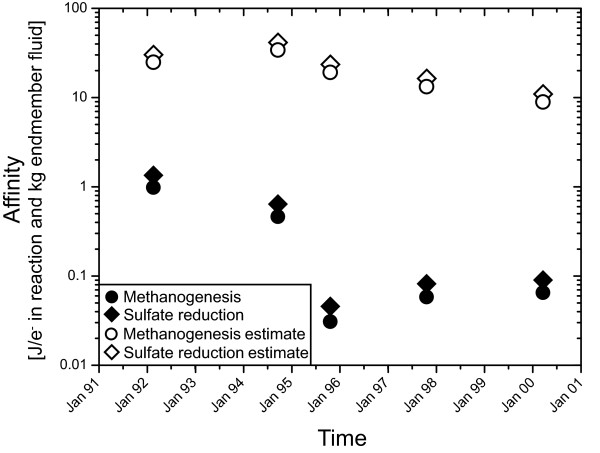

Affinity calculations for hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis and sulfate reduction in the modeled fluid (Figure 5) indicate strong driving forces for both reactions. The affinity for the reaction is strongly controlled by the hydrogen activity, which has a power of 4 in the relevant mass action equations. Hydrogen endmember concentrations increase from 6460 μM in February/March of 1992 to 8910 μM in March of 1994. Hydrogen concentrations then decrease in the following years to 2700 μM in April of 2000 (Table 1). Unfortunately, the time series contains three points with data lacking for either the diffuse or endmember fluid. In March of 1994, the highest hydrogen concentration in the endmember fluid was measured, but no diffuse fluid was sampled. Hence, in our calculations, the sample collected in October of 1994 has the highest predicted hydrogen content (Figure 4) and also the highest normalized affinity for methanogenesis with 34.0 Joule per kg vent fluid and electron transferred in reaction (J/kg e-) or of 41.5 J/kg e- for sulfate reduction in the predicted diffuse fluid (Figure 5). The fluids sampled in April of 2000 have the smallest fraction of vent fluid and the lowest hydrogen endmember concentration of 12.5 μM, yielding normalized affinities for methanogenesis of 8.9 J/kg e- and 11.0 J/kg e- for sulfate reduction. In these diffuse fluids, hydrogen concentrations are still lower than predicted from conservative mixing and they do not correlate with the endmember concentration or extent of mixing with seawater.

Figure 5.

Normalized affinities for sulfate reduction and methanogenesis in the Tube Worm Pillar area. Affinities are high in the hypothetical fluids calculated from conservative mixing of seawater and hydrothermal fluid. In the measured fluids the affinity is strongly decreased. Notably, affinities drop markedly in the first three years, which reflects the decrease in H2 concentration in that time span (Figure 4). The removal of H2 and the lowering of affinity reflect the exploitation of H2 in fueling catabolic activity. During the last five years of the time series, normalized affinities had plateaued, possibly indicating a steady-state between hydrothermal energy supply and microbial utilization of energy.

Overall, hydrogen concentrations decrease linearly within the first four years of the time series from 14.9 μM to 0.7 μM. Hydrogen concentrations then remain fairly constant in the range of 0.7 to 0.2 μM until 2000. Figure 5 shows the affinities of these reactions per mol electrons in the reaction and normalized to kg of vent fluid. The normalized affinities of sulfate reduction decrease from 1.4 J/kg e- to 0.05 J/kg e- in 1995 and rebounds to 0.08-0.09 J/kg e- in the following years. Hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis has an affinity of 1.0 J/kg e- in 1992 and decreases to 0.05 to 0.06 J/kg e- in 1995 - 2000 (Table 2).

The differences in the affinities (Table 2) reflect the variability in hydrogen concentrations, but the magnitude of these differences is quite small, because the intensive term (ΔrG°) in the Gibbs energy calculation is very large for both reactions. The calculated affinities for methanogenesis and sulfate reduction (Table 2) lie above the estimated energy limit of microbial metabolism 10 kJ/8 e- [33]. Minimum H2 concentrations required for microbial harnessing of hydrogen at the temperatures of diffuse venting (11.9 to 24.7°C) is on the order of 10-8 M [33], which is considerably lower than the measured concentrations (> 2 × 10-7 M). This result indicates that the microbial communities consume hydrogen but do not control its abundance. Apparently, hydrothermally driven influx of H2 into the system is overall greater than the rate at which H2 is metabolized. The constant hydrogen concentrations between 1995 and 2000 probably indicate some sort of steady-state between influx of hydrogen from below and hydrogen consumption in the subseafloor ecosystem. The early phase of decreasing hydrogen concentrations in the diffuse fluids is not related to changes in endmember compositions (steady between 250 and 350 μM), but may instead reflect the growth a hydrogenotrophic microbial community and increasing rates of consumption of H2 advected into the system by hydrothermal flow. In that early stage, there was a relation between H2 depletion and methane production, indicating that methanogenesis was responsible for both. In 1997 and 2000, H2 was still consumed, but the methane excess had disappeared. Instead, there was excess Fe in the fluids, suggesting that Fe-reduction was taking place, perhaps because it requires lower H2 activities than methanogenesis [33].

Conclusions

Thermodynamic calculations of energy yields of catabolic reactions from geochemical data of diffuse fluids facilitate an assessment of microbial metabolism in vent settings. This has been demonstrated in two case studies, both from the EPR 9°50'N region, where published geochemical data [13,14] where used in systematic calculations of affinities of different catabolic reactions.

In the Bio9 area, affinities for sulfide oxidation strongly decrease, which is in accordance with the dying Riftia population. At the same time, an increase in the affinity for iron oxidation corresponds to a massive spread of red staining in the area, which is likely evidence for Fe-oxidizing bacteria. The results of the energy calculations verify the idea that the sudden change in vent fauna is a result of changes in fluid chemistry.

The example from the Bio9 area is more relevant to subseafloor processes. Enrichment of methane in diffuse fluids points to methanogenesis in the mixing and cooling zone. Our calculations confirm that hydrogenotrophic catabolic reactions have large energy yields throughout the duration of the time series (1992-2000). A large discrepancy in the amount of H2 predicted from conservative mixing and the measured H2 concentrations indicate effective scrubbing of H2 by subseafloor hydrogenotrophic microorganisms. During the first three years of the time series, affinities for hydrogenotrophic reactions decreased despite continued high H2 concentrations in the endmember fluids. This is interpreted to indicate the development of a hydrogenotrophic-based microbial ecosystem in the subseafloor. Between 1995 and 2000, the affinities remained constant and low (about an order of magnitude above the biological energy quantum). Apparently, influx of hydrogen from below and consumption of hydrogen within the subseafloor had reached a steady state. In 1997 and 2000, methane excesses were minimal, but the fluids showed pronounced enrichment of Fe relative to the concentrations predicted from conservative mixing. This finding may indicate a switch within the system from methanogenesis to Fe-reduction.

Our results show how thermodynamic calculations can be used to examine the relations between changes in fluid chemistry and seafloor biology. They are also a helpful tool in examining processes in the subseafloor and help highlight the tight relations and interdependencies between geochemistry and microbiology in vent systems.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

The study was developed jointly by both authors. MH conducted the thermodynamic calculations. Both authors were involved equally in the interpretations of the results and in writing and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Table: Calculated normalized affinities for Aerobic sulfide oxidation and iron oxidation in J per e- and kg Vent-fluid at the Northern Area (Bio9). Additional Data to Figure 3

Contributor Information

Michael Hentscher, Email: hentscher@uni-bremen.de.

Wolfgang Bach, Email: wbach@uni-bremen.de.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for numerous helpful comments and suggestions and to Greg Druschel for efficient editorial handling. This work was funded through the German Research Foundation (Grant BA1605/6-1). WB acknowledges additional support through the University of Bremen and the MARUM Research Center and Cluster of Excellence.

References

- Jannasch HW. In: Seafloor Hydrothermal Systems: Physical, Chemical, Biological, and Geological Interactions. Humphris SE, et al, editor. Vol. 91. Washington, DC: American Geophysical Union, American Geophysical Union; 1995. Microbial interactions with hydrothermal fluids; pp. 273–273. Geophysical Monograph. [Google Scholar]

- McCollom TM, Shock EL. Geochemical constraints on chemolithoautotrophic metabolism by microorganisms in seafloor hydrothermal systems. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1997;61:4375–4391. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(97)00241-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amend JP, McCollom TM, Hentscher M, Bach W. Catabolic and anabolic energy for chemolithoautotrophs in deep-sea hydrothermal systems hosted in different rock types. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2011;75:5736–5748. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2011.07.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shock E, Holland ME. In: The Subseafloor Biosphere at Mid-Ocean Ridges. Wilcock WSD, DeLong EF, Kelley DS, Baross JA, Cary SC, editor. Washington, DC: American Geophysical Union; 2004. Geochemical energy sources that support the subsurface biosphere; pp. 153–165. Geophysical Monograph. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton JL, Seyfried WE Jr. An experimental and theoretical approach to determining linkages between geochemical variability and microbial biodiversity in seafloor hydrothermal chimneys. Geobiology. 2010;8:457–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2010.00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber JA, Butterfield DA, Baross JA. Bacterial diversity in a subseafloor habitat following a deep-sea volcanic eruption. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 2003;43:393–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2003.tb01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reysenbach A-L, Liu Y, Banta AB, Beveridge TJ, Kirshtein JD, Schouten S, Tivey MK, Von Damm KL, Voytek MA. A ubiquitous thermoacidophilic archaeon from deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Nature. 2006;442:444–447. doi: 10.1038/nature04921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kormas KA, Tivey MK, Von Damm K, Teske A. Bacterial and archaeal phylotypes associated with distinct mineralogical layers of a white smoker spire from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent site (9°N, East Pacific Rise) Environmental Microbiology. 2006;8:909–920. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perner M, Bach W, Hentscher M, Koschinsky A, Garbe-Schönberg D, Streit WR, Strauss H. Short-term microbial and physico-chemical variability in low-temperature hydrothermal fluids near 5°S on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Environmental Microbiology. 2009;11:2526–2541. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen JM, Zielinski FU, Pape T, Seifert R, Moraru C, Amann R, Hourdez S, Girguis PR, Wankel SD, Barbe V. et al. Hydrogen is an energy source for hydrothermal vent symbioses. Nature. 2011;476:176–180. doi: 10.1038/nature10325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amend JP, Shock EL. Energetics of overall metabolic reactions of thermophilic and hyperthermophilic Archaea and Bacteria. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2001;25:175–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson HC. Mass transfer among minerals and hydrothermal solutions. Geochemistry of hydrothermal ore deposits. 1979;2:568–610. [Google Scholar]

- Von Damm KL, Lilley MD. In: The Subseafloor Biosphere at Mid-Ocean Ridges. Wilcock WSD, DeLong EF, Kelley DS, Baross JA, Cary SC, editor. Washington, DC: American Geophysical Union; 2004. Diffuse flow hydrothermal fluids from 9 50'N East Pacific Rise: evolution and biogeochemical controls; pp. 245–268. Geophysical Monograph. [Google Scholar]

- Von Damm KL. In: Mid-Ocean Ridges: Hydrothermal Interactions between the Lithosphere and Oceans. German CR, Lin J, Parson LM, editor. Washington, DC: American Geophysical Union; 2004. Evolution of the hydrothermal system at East Pacific Rise 9 50'N: Geochemical evidence for changes in the upper oceanic crust; pp. 285–304. Geophysical Monograph. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll S, Mroczek E, Alai M, Ebert M. Amorphous silica precipitation (60 to 120°C): comparison of laboratory and field rates. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1998;62:1379–1396. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(98)00052-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edmond JM, Measures C, McDuff RE, Chan LH, Collier R, Grant B, Gordon LI, Corliss JB. Ridge crest hydrothermal activity and the balances of the major and minor elements in the ocean: The Galapagos data. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 1979;46:1–18. doi: 10.1016/0012-821X(79)90061-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bethke C. Geochemical reaction modeling: Concepts and applications. Oxford University Press, USA; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JW, Oelkers EH, Helgeson HC. SUPCRT92: A software package for calculating the standard molal thermodynamic properties of minerals, gases, aqueous species, and reactions from 1 to 5000 bar and 0 to 1000°C. Computers & Geosciences. 1992;18:899–947. doi: 10.1016/0098-3004(92)90029-Q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dick J. Calculation of the relative metastabilities of proteins using the CHNOSZ software package. Geochemical Transactions. 2008. p. 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wolery T, Jove-Colon C. In: Energy. US Department of Energy, editor. Bechtel SAIC Company, Las Vegas, Nevadam, USA; 2004. Qualification of thermodynamic data for geochemical modeling of mineral-water interactions in dilute systems. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond SE. Ph D thesis. University Microfilms Int.; 1981. Boiling and mixing of hydrothermal fluids. [Google Scholar]

- Tivey MK, Humphris SE, Thompson G, Hannington MD, Rona PA. Deducing patterns of fluid flow and mixing within the TAG active hydrothermal mound using mineralogical and geochemical data. J Geophys Res. 1995;100:12527–12555. doi: 10.1029/95JB00610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foustoukos DI, Houghton JL, Seyfried WE Jr, Sievert SM, Cody GD. Kinetics of H2-O2-H2O redox equilibria and formation of metastable H2O2 under low temperature hydrothermal conditions. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2011;75:1594–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2010.12.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCollom TM. Geochemical constraints on sources of metabolic energy for chemolithoautotrophy in ultramafic-hosted deep-sea hydrothermal systems. Astrobiology. 2007;7:933–950. doi: 10.1089/ast.2006.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornari DJ, Shank T, Von Damm KL, Gregg TKP, Lilley M, Levai G, Bray A, Haymon RM, Perfit MR, Lutz R. Time-series temperature measurements at high-temperature hydrothermal vents, East Pacific Rise 9°49'-51'N: evidence for monitoring a crustal cracking event. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 1998;160:419–431. doi: 10.1016/S0012-821X(98)00101-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn RA, Fornari DJ, Von Damm KL, Hildebrand JA, Webb SC. Seismic and hydrothermal evidence for a cracking event on the East Pacific Rise crest at 9° 50' N. Nature. 1998;396:159–161. doi: 10.1038/24146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shank TM, Fornari DJ, Von Damm KL, Lilley MD, Haymon RM, Lutz RA. Temporal and spatial patterns of biological community development at nascent deep-sea hydrothermal vents (9°50'N, East Pacific Rise) Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography. 1998;45:465–515. doi: 10.1016/S0967-0645(97)00089-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh CM. Symbiotic chemoautotrophic bacteria in marine invertebrates from sulphide-rich habitats. Nature. 1983;302:58–61. doi: 10.1038/302058a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toner BM, Santelli CM, Marcus MA, Wirth R, Chan CS, McCollom T, Bach W, Edwards KJ. Biogenic iron oxyhydroxide formation at mid-ocean ridge hydrothermal vents: Juan de Fuca Ridge. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2009;73:388–403. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2008.09.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Betts JN, Holland HD. The oxygen content of ocean bottom waters, the burial efficiency of organic carbon, and the regulation of atmospheric oxygen. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 1991;97:5–18. doi: 10.1016/0031-0182(91)90178-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proskurowski G, Lilley MD, Olson EJ. Stable isotopic evidence in support of active microbial methane cycling in low-temperature diffuse flow vents at 9°50'N East Pacific Rise. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2008;72:2005–2023. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2008.01.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schouten S, Wakeham SG, Hopmans EC, Sinninghe Damste JS. Biogeochemical evidence that thermophilic archaea mediate the anaerobic oxidation of methane. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:1680–1686. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.3.1680-1686.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehler TM. Biological energy requirements as quantitative boundary conditions for life in the subsurface. Geobiology. 2004;2:205–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4677.2004.00033.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table: Calculated normalized affinities for Aerobic sulfide oxidation and iron oxidation in J per e- and kg Vent-fluid at the Northern Area (Bio9). Additional Data to Figure 3