Abstract

The Toxin Complex (TC) is a large multi-subunit toxin first characterized in the insect pathogens Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus, but now seen in a range of pathogens, including those of humans. These complexes comprise three protein subunits, A, B and C which in the Xenorhabdus toxin are found in a 4∶1∶1 stoichiometry. Some TCs have been demonstrated to exhibit oral toxicity to insects and have the potential to be developed as a pest control technology. The lack of recognisable signal sequences in the three large component proteins hinders an understanding of their mode of secretion. Nevertheless, we have shown the Photorhabdus luminescens (Pl) Tcd complex has been shown to associate with the bacteria's surface, although some strains can also release it into the surrounding milieu. The large number of tc gene homologues in Pl make study of the export process difficult and as such we have developed and validated a heterologous Escherichia coli expression model to study the release of these important toxins. In addition to this model, we have used comparative genomics between a strain that releases high levels of Tcd into the supernatant and one that retains the toxin on its surface, to identify a protein responsible for enhancing secretion and release of these toxins. This protein is a putative lipase (Pdl1) which is regulated by a small tightly linked antagonist protein (Orf53). The identification of homologues of these in other bacteria, linked to other virulence factor operons, such as type VI secretion systems, suggests that these genes represent a general and widespread mechanism for enhancing toxin release in Gram negative pathogens.

Author Summary

Bacterial pathogens of insects deploy a range of toxins to combat the innate immune system and kill the host. There is significant interest in developing these toxins as candidates for crop protection strategies. To date, transgenic crops expressing Bacillus thuringiensis Cry toxins have been used to resist predation by pests. In order to minimize the risk of insect resistance development, current research in crop biotechnology comprises the design of new transgenic plants expressing toxins with different modes of action. The Toxin Complex (TC) gene family first identified in the insect pathogen Photorhabdus has received interest as an alternative. It remains obscure how Photorhabdus regulates, assembles, and secretes such a large toxin complex. We have identified a small lipase protein, Pdl1, which enhances secretion and leads to the release of the Toxin complex off the bacterial surface. This is of wider significance because TC toxin homologues are also found in a range of human pathogens, such as Yersinia in which they have been implicated in human virulence. Furthermore homologues of pdl are also seen tightly linked to other virulence loci such as the type VI systems of Vibrio. We speculate that this Pdl mediated secretion enhancement system is a widespread and important mechanism used by Gram negative bacterial pathogens.

Introduction

Photorhabdus are Gram-negative members of the Enterobacteriaceae that live in a symbiotic association with entomopathogenic nematodes which invade and kill insects. Upon insect invasion the nematode regurgitates the bacteria which grow within the insect open blood system releasing a plethora of toxins and insecticides, to kill the insect and protect the cadaver from invading microbes, scavengers and saprophytes [1]. One major class of secreted insecticidal toxins are the Toxin Complex (TC) proteins [2]–[3]. They constitute large multimeric protein complexes that have been shown to exhibit oral toxicity to a range of insects including crop pests [4]–[5]. These complexes consist of three protein subunit types; homologues of TcdA TcdB and TccC proteins, from here on referred to simply as A, B and C-subunits respectively [6]. These protein subunits themselves are large with the TcdA1, TcdB1 and TccC5 being 2517 aa (283 kDa), 1477 aa (165 kDa) and 939 aa (105 kDa) respectively. Recent work on a Xenorhabdus nematophilus TC suggests that the A (XptA2), B (XptB1) and C (XptC1) subunits are in a 4∶1∶1 stoichiometry respectively [7]–[8]. There is now reasonable evidence to indicate that the A subunit forms a cage-like tetramer of around 1120 kDa which associates with a tightly bound 1∶1 sub-complex of B and C. The A subunits can bind the host cell membranes of insect brush border cells and form a pore facilitating the entry of the BC sub-complex [8]–[9]. The toxic activity of the complex resides in the C-terminal region of the C subunit. The TCs represent a potential target to augment the successful B. thuringiensis crystal toxin crop protection technology and have been the subject of significant investment by the agrochemical industry. The availability of a large number of bacterial pathogen genome sequences has revealed that TC toxins are not restricted to Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus sp., but are in fact widely distributed [2]. This includes Gram-negative human pathogens such as Yersinia and Burkholderia and a Gram-positive insect pathogen such as B. thuringiensis strain IBL200 (accession NZ_ACNK01000119). Although the role of these TC homologues in most pathogens remains obscure, recent work in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis has suggested that homologues of these toxins have been adapted to act upon the mammalian gut [10]. They have also been implicated in mammalian gut colonisation in at least one strain of Y. enterocolitica [11].

Some progress has been made in TC research including the reconstitution of TC function through heterologous expression of the three essential subunits, A, B and C, in E. coli [3], [8], [12]–[13], expression of partial activity in transgenic plants [14] and the analysis of TC homologues from other species of bacteria [10], [15]. In addition TC toxins have also been heterologously expressed in Enterobacteria species which associate with termites as a control strategy [16]. Most recently Lang et al demonstrated the mode of action of certain C-subunit C-terminal domains in the ADP-ribosylation of actin and RhoA [9]. Nevertheless, efforts in understanding the biological context of TC have been hampered by an incomplete understanding of how Gram-negative bacteria are able to assemble and secrete such large multimeric protein complexes.

The tc gene homologues are encoded at several different loci in the Photorhabdus genome and in strain Pl W14, two of these loci, tca and tcd were shown to be responsible for oral toxicity to Manduca sexta larvae [4], [17]. The tcd locus is a large pathogenicity island (pai) containing multiple homologues of the A, B and C-subunit genes in tandem [18]. Previously we used RT-PCR and western blotting to demonstrate that Pl W14 expresses both the tca and tcd loci genes during insect infection [19]–[20]. Previous work has shown that the A and B+C-subunits are capable of exhibiting oral toxicity independently when expressed at high levels, yet nevertheless assemble into a far more potent large multimeric complex [8], [21].

We noted that strains belonging to the species P. luminescens could be classified into two distinct biotypes, some produced Tcd which remained attached to the cell surface (e.g. strain Pl TT01), while others also released it into the surrounding medium (e.g.; Pl W14) (Fig. 1AB). We hypothesized that there would be specific genetic factors facilitating this variation in TC deployment. We have used comparative genomics between a strain that releases Tcd and a strain that does not, together with a cosmid based E. coli heterologous expression system to investigate this hypothesis. Here we present evidence that toxin secretion is enhanced by a lipase (Pdl1), the activity of which is controlled by a small tightly linked antagonist protein (Orf53). Homologues of these genes can be seen to be linked to many virulence loci in other pathogens and we suggest that this work represents the first characterised example of an important and widespread secretion enhancement mechanism.

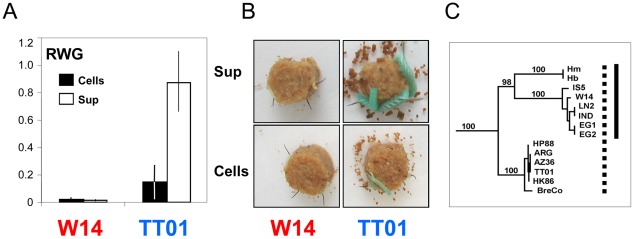

Figure 1. Oral toxicity in P. luminescens strains W14 and TT01.

(A) Oral toxicity of cells (cells) and supernatants (sup) of P. luminescens strains W14 and TT01 against M. sexta neonates. A cohort of 20 larvae each were tested by oral bioassay on food blocks overlaid with 100 µl of undiluted 3 day old culture supernatants and the equivalent of saline washed cells. Cell numbers added to each block were adjusted to 2×108 cells per block. Relative Weight Gain (RWG), means and standard errors are shown. Data is normalised against an E. coli EC100 negative control (which would give a mean weight of 1). (B) Illustration of the differential toxicity of cells and supernatants of W14 and TT01 against M. sexta neonates after seven days consuming the treated artificial diet. (C) P. luminescens phylogenetic relationship based on MLST analysis. Note that while all these strains produce the oral toxin Tcd on the cell surface (dotted bar), that those in the clade with strain W14 (solid bar) are also able to release it into the supernatant.

Materials and Methods

Cosmid identification and insertional mutagenesis

The c1AH10 was identified from a Pl W14 cosmid library [18] by aligning cosmid end sequences to the tcd pai sequence using SeqMan. The E. coli c1AH10 clone was tested for oral toxicity as described below. Insertional mutagenesis was performed with EZ::TN<TET1> transposon (Epicentre) to generate and characterise an insertion mutant sub-library as previously described [22]. Briefly, insertion mutant cosmid clone colonies were picked and DNA was prepared on a RoboPrep plasmid preparation robot (MWG Biotech). The insertion site of the transposon in each mutant was determined by sequencing out from the transposon with a transposon specific primer using an ABI3700 nucleotide sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Sequences were assembled onto the c1AH10 template sequence by using the LASERGENE software package (DNASTAR, Madison, WI) allowing the transposon insert sites to be determined.

Cloning and recombinant expression of pdl1 and flanking genes orf54 and orf53

The pdl1, orf54 and orf53 genes were amplified from P. luminescens strain W14 genomic DNA using rTth DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) conditions were 1.2–1.6 mM magnesium acetate, 2 mM each dNTP and 1 mM each primer. Thermocycling was performed as follows: 93°C for 30 s; 55°C for 30 s and 68°C for 3 min, for 30 cycles and a final 68°C incubation for 10 min. PCR primers, used for cloning into pET-28a(+), pCDF-1b (Novagen), and the arabinose inducible expression plasmid pBAD30 were designed to include unique restriction sites for subsequent cloning. The primer sequences (5′ to 3′) used for cloning the pdl1, orf54 and orf53 genes into pBAD30 were as follows:

-

pdl1 only: w14PDL-XbaIf: ATTcTAgaGGAAAGAGTATCAATGAGC;

w14PDL-HindIII R: ATaagcttTCATACAGACAGTTCC;

-

pdl1 and its upstream region: Nco-5-P-pdl: CCccatggACTCCTTAGATGGTGTTAATCG;

BamH-3-pdl: TCggatccTCATACAGACAGTTCCTG;

pdl1 + orf54 : w14short-HindIIIR: ATaagcttTTACTTTATGTAACGGG;

pdl1 + orf54+orf53 : w14long-HindIIIR: ATaagcttTACTTTATTTTCCAGTAG.

For His-tagged cloning, pdl1 and orf54 were initially cloned into pET-28a(+) as His-fusion proteins and then subsequently PCR amplified from this template as a His-fusion for cloning into pBAD30. The primer sequences (5′ to 3′) were as follows:

W14PDL-XbaIf: ATTcTAgaGGAAAGAGTATCAATGAGC;

28a-r-XhoI-pdl: ATATATCTCGAGTACAGACAGTTCCTGT;

30-r-SphI-PET28: ATATATGCATGCTAGTTATTGCTCAGCGG;

W14O53-XbaIF: ATTCTAGAATCTAAATGCCAACATGAG;

28a-r-XhoI-O53: ATCTCGAGCTTTATTTTCCAGTAGTC.

Following PCR, the products were purified (Millipore Montage PCR column as per instructions), cut with the appropriate restriction enzyme, and then re-purified prior to ligation and cloning. Plasmid DNA from pET-28a(+), pBAD30 and pCDF-1b expression vectors was prepared (Qiagen miniprep kit as per instructions) and co-digested with the relevant restriction enzymes. Ligations were performed at a 3∶1 molar excess of insert to vector using the Promega T4 DNA ligase rapid ligation system. Aliquots of the ligation reaction containing pET-28a(+) or pBAD30 vectors were electroporated into Epicentre Transformax EC100 E. coli and recovered on Luria–Broth (LB) agar containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin. Ligation containing pCDF-1b vector was transformed into chemically competent BL21 E. coli (Invitrogen) and recovered on LB agar containing 50 µg/ml Streptomycin. Correct constructs were selected by restriction digest of DNA prepared from candidate clones and verified by subsequent sequencing and stored at −80°C in 15% glycerol. Positive clones were subsequently induced for protein expression. Glycerol stocks were used to inoculate 5 ml of fresh LB media supplemented with 0.2% glucose (w/v) and the appropriate antibiotic for selection. Bacteria were grown overnight at 37°C with shaking, 1 ml of this culture was then harvested and resuspended in 100 ml of the same media and incubated at 37°C until an OD600 of 0.7–0.9 was achieved. Cells were then harvested at room temperature by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 min. The pellet was re-suspended in 100 ml of fresh LB, supplemented with the appropriate antibiotic and 0.2% (w/v) of the pBAD30 promoter inducer L-arabinose or 1 mM IPTG for pCDF-1b construct. Cells or trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitated and concentrated supernatants from overnight induced cultures were collected for analysis using SDS-PAGE to confirm expression.

Complementation assays

The c1AH10 derived cosmids containing transposon insertions into the pdl1 gene (pdl1 KO1-mutant) or in the pWEB vector backbone (CVI-wt) were isolated from the E. coli Pl W14 library clones and each transformed into chemically competent E. coli BL21 cells. To complement the mutant pdl1 gene, E. coli BL21 cells were co-transformed with both the pdl1 KO1-mutant cosmid and the pCDF-1b:pdl1 construct. Transformant clones were recovered on LB agar containing the appropriate antibiotics. Positive clones containing both constructs were confirmed both by colony PCR and by DNA isolation and identification of cosmid and plasmid DNA using gel electrophoresis. Single colonies were subcultured in 5 ml of LB with the appropriate antibiotics and were grown overnight at 28°C with shaking. Larger subcultures were inoculated with these overnight pre-cultures (1/100 v/v dilution) and grown at 28°C with shaking for 72 h to be used in bioassays. Whole cultures, washed cells and supernatants were used in the M. sexta neonate feeding bioassays.

Oral bioassay against Manduca sexta caterpillars

Supernatants or washed cells were diluted in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and applied to 1 cm3 disks of artificial wheat germ diet as previously described [13]. Treated food blocks were allowed to dry for 30 min and two neonate M. sexta larvae were placed on each food block before incubation at 25°C for 7 days. Larvae were then scored for mortality and weighed. Larval growth differences are then expressed either as the direct mean values or as relative weight gain (RWG) means normalised to control groups [13]. The control groups are typically E. coli culture conditioned medium. RWG means are calculated using the following formula: RWG mean = 1+((sample mean−control mean)/control mean).

Cell fractionation

P. luminescens W14 (Pl W14) was electroporated with various expression constructs using a standard E. coli optimised protocol. Transformants were confirmed by restriction digest of plasmid DNA prepared using a Qiagen kit as per manufacturer's protocol. Pl W14 carrying the pdl1 or orf53 expression constructs were induced with arabinose and cultured for different time points (3 h, 1 day and 2 days). Cells were washed in 1× PBS, normalized to an optical density of 10.0, and lysed by sonication (10 s on and 10 s off 45% power regime for 3 min). Unbroken cells were removed by low speed centrifugation. One millilitre of each cell-free lysate was fractionated into the soluble (cytoplasm and periplasm) and insoluble (inner and outer membrane) fractions by ultracentrifugation (28 000 r.p.m. for 2 h in a Beckman SW40Ti rotor). The insoluble fraction was resuspended in 1 ml of PBS to restore its original concentration relative to the soluble fraction proteins in the lysate. Supernatant samples were prepared and concentrated using TCA precipitation.

Western blot

Protein sample amounts and quality were initially assessed by standard Coomassie blue staining of SDS-PAGE gels. For western blotting, protein fractions were separated by 1 dimensional SDS-PAGE and western blotted onto Nitrocellulose using a Biorad semi-dry blotter. We probed these membranes using a standard protocol with the following antibodies: TcdB1 (C terminal) anti-peptide antibody (raised against aa856- YSSSEEKPFSPPNDC-aa869), monoclonal anti-poly-histidine antibody (SIGMA), anti-β-Lactamase antibody (Millipore) and anti-SecG (a kind gift from Prof. Hajime Tokuda, University of Morioka). Immune-reactive bands were visualized using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibody (SIGMA) at 1∶5000 and developed using NBT-BCIP agent. Anti-β-Lactamase western blots were performed to ensure no contamination of soluble material in the membrane fraction and anti-SecG western blots ensured no contamination of the membrane material in the soluble fraction.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from normalised cell number samples (OD600 of 0.5) of E. coli or W14 cells at different time points using RNeasy kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's protocol. In all cases, the RNA was initially quality controlled by performing a standard Taq PCR reaction, using the intended primer pairs to ensure no contaminating DNA. RT-PCR was performed using One-step RT-PCR kit (QIAGEN). Thermocycling was performed as follows: 50°C for 30 min; 95°C for 15 min; 94°C for 30 s; 50°C for 30 s and 72°C for 1 min, for 25 cycles and a final 72°C incubation for 10 min. Primers, which were designed to include unique sequence of different target genes, were described as follows (5′-3′):

tccC5-F: CAGGCGGAACAGGTGATTAT; tccC5-R GAGTTGGATCTGCGGTCAAT;

tcdA1-F: TTGAGAGCGTCAATGTCCTG; tcdA1-R; TATCCGCGGCTCTGTCTAGT;

tcdB1-F: TGGAAGCCTCGATATCATCC; tcdB1-R: ATAGGCCAGTTCCAGTGGTG;

orf53-F: AAATTACGTCTGGATGTGAAG; orf53-R: CCAGTAGTCTATCGTTTGGCG;

pdl-F: GGGAACAATAAGCAGGGTGA; pdl-R: GGTGACGGCGATAACAACTT;

tccC2-F: ATCGGGGTGTTCTCAGTACG; tccC2-R: TTCTGTTTGGCTGTTTGCTG

Haemolysis assays

(i) Plate assay: E. coli carrying pBAD30-pdl1 were plated onto LB agar supplemented with ampicillin (100 µg/ml) and sheep red blood cells (SIGMA). For induction of pdl1 expression 0.2% (w/v) arabinose was also included. Plates were incubated at 37°C overnight before visualisation. (ii) Liquid assay: These were performed as described elsewhere [23]. Briefly, washed cells were isolated from induced and un-induced pBAD30-pdl1 cultures and sonicated. For induction, 0.2% (w/v) arabinose was added to cultures during exponential growth phase. Subsequently, 50 µl of red blood cells were suspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), added to 150 µl of either control buffers, induced or un-induced bacterial lysate before incubation at 37°C. After 24 hours, the whole red blood cells were removed by centrifugation at 5 rpm for 5 min, and the extent of haemoglobin release within the reaction supernatant was measured at an optical density of 540 nm in a spectrophotometer. Percentage haemolysis was calculated as [(OD540 treatment sample/OD540 total lysis)×100].

Accession numbers

NCBI accession numbers for the proteins/genes described in this study are as follows: Pdl1, AAL18491; Orf53, AAL18489; TcdA1, AAL18486; TcdB1, AAL18487; TccC5, AAO17210; Orf54, AAL18490; Orf47, AAL18483 and Orf48, AAL18484.

Results

TC secretion by different strains of Photorhabdus luminescens

We compared M. sexta oral toxicity data with a phylogenetic analysis of the P. luminescens species [24]–[25]. Members of the clade exemplified by strain Pl W14 all produce orally toxic supernatants and cells, while those in the clade which include strain Pl TT01 exhibit orally toxic cells but not supernatants (Fig. 1C). It is important to note here that we are talking about toxicity and not infection as P. luminescens cannot infect the model insect M. sexta via the oral route. Despite this, limited microarray analysis confirmed that all P. luminescens strains encode homologues of the oral toxins tcdA1 and tcdB1 genes [26], suggesting other lineage specific genetic factors might control the release of the orally toxic Tcd complex off the cell and into the surrounding medium. Previous work has identified the tca and tcd locus in Pl W14 as responsible for oral toxicity to M. sexta [4]. With the availability of the Pl TT01 genome sequence [27] and the sequences of several tc loci of Pl W14 [20] we have been able to directly compare the tca and tcd loci. The tca locus has undergone genetic degradation in Pl TT01 and so cannot contribute to oral toxicity. Conversely the Pl TT01 and Pl W14 tcd pathogenicity islands are well conserved, although the Pl W14 locus also contains a number of additional genes absent from Pl TT01 (Fig. 2A). We speculated that these genes are responsible for the release of Tcd into the surrounding supernatant in Pl W14, and without them, the majority of the Tcd complex remains associated with the cell surface in Pl TT01. Previous immuno-gold localisation studies using a Tca polyclonal antibody to probe thin sections of Pl W14 confirmed that TC cross-reactive antigens were indeed localised on the surface of the bacterial cells [19].

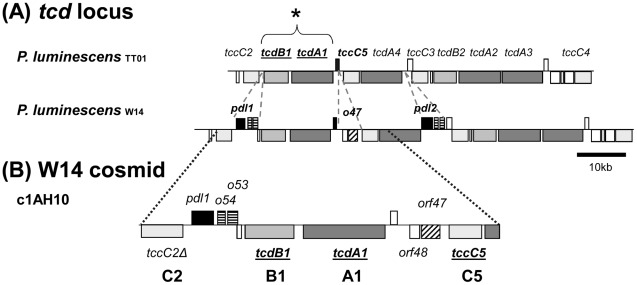

Figure 2. The tcd Pathogenicity islands of P. luminescens.

(A) A comparison of the tcd pathogenicity islands (pai) of P. luminescens strains TT01 and W14. Note in the tcd pai, it is the tcdA1 and tcdB1 genes previously that have been associated with oral toxicity to M. sexta (see *). Several genes present in the Pl W14 tcd pai which are absent from Pl TT01 are indicated by the dotted lines. These include pdl1 and pdl2 (filled black) which are predicted lipases and orf54 homologues (horizontal stripes) which have type II secretion leader peptides. The orf47 predicted gene product (diagonal stripes) also has a predicted lipase domain and the downstream orf48 protein also has a type II secretion leader peptide. This suggests analogous roles to pdl1 and orf47. (B) A Pl W14 cosmid clone (c1AH10) that is sufficient to allow E. coli to produce both cell associated and freely secreted oral toxicity similar to Pl W14. This cosmid contains intact copies of all three tc homologues (subunits A+B+C) known to be necessary for producing full oral toxicity. Note the tccC2 gene is N-terminally truncated and not functional on this clone.

A heterologous expression model to study Tcd export

To study Tcd export we developed a heterologous model for expression and secretion in E. coli. Previously we PCR screened a Pl W14 cosmid library for clones that encompassed the tcdA1B1 genes [18] and tested them for the production of orally toxic supernatants. We confirmed that cosmid c1AH10 produced both supernatant and cell associated oral toxicity, consistent with the Pl W14 phenotype. This cosmid encodes intact copies of all three necessary subunit genes, A, B and C, (tcdA1 tcdB1 and tccC5), required for full toxicity (Fig. 2B). Nevertheless the roles of other genes on this cosmid were not known. Two small Pl W14 specific islands are present on this cosmid. The first small island encodes a gene named pdl1, the predicted protein product of which contains putative lipase and protease domains, in addition to two small self-similar tightly linked ORFs (orf53 and orf54) each with type II secretion signal peptides but no other recognisable domains. The second island contains the genes orf47, which also has a predicted esterase/lipase domain but is unrelated to pdl, and orf48 which again has a putative signal peptide leader sequence but no other recognizable domains. To validate this cosmid as a suitable model for studying Tcd expression and secretion we compared the transcription and translation of several genes on c1AH10 in E. coli with those in the original Pl W14 strain across the growth curve using RT-PCR (Fig. S1) and western blot analysis (Fig. S2B). RT-PCR analysis revealed that the A, B and C-subunit gene transcripts are present at all growth phases, but decline by 3 days. A similar trend in transcriptional levels is seen for both the cosmid and the W14 strains supporting its relevance as a model system. We note a peak in pdl1 mRNA at the late phase of growth (OD = 2, around 8 h for W14) especially in the cosmid clone which is consistent with the onset of toxin secretion.

We designed an anti-peptide antibody against the C-terminus of the B-subunit (TcdB1) and used this to track the translation and location of the Tcd complex. We do not see B-subunit translation in either strain Pl W14 or the cosmid clone until 24 hours (Fig. S2A), which correlates with the appearance of the oral toxicity phenotype. The failure of the antibody to cross react with supernatant proteins from a W14 tcdAB KO strain [4] confirms the specificity of this antibody for the TcdB1 subunit. When Tcd is produced by Pl W14 and the cosmid clone, it is present in the membrane and supernatant fractions (Fig. S2B). This correlates with whole-cell and supernatant associated oral toxicity of both the cosmid clone and Pl W14. Nevertheless, as previously seen, the overall levels of Tcd production are low [28].

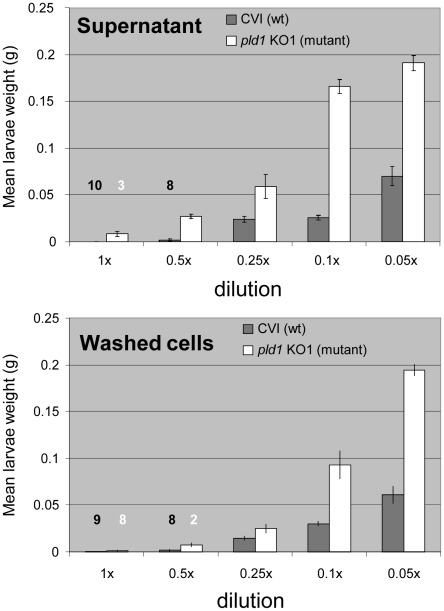

Pdl1 enhances Tcd mediated cell surface and supernatant toxicity

An in vitro transposon mutagenesis kit was used to create a library of transposon mutants of cosmid c1AH10. Insertion knock-out mutants in all genes were identified by sequencing out from the transposon into the flanking cosmid sequence. The oral toxicity of cells and supernatants of this panel of cosmid mutants (in E. coli) was then examined by M. sexta oral bioassay. As expected this confirmed that all the three subunit genes were required for toxicity in E. coli (at least under these “native” expression levels). In addition however we can see that insertion mutagenesis of pdl1 significantly lowered toxicity of the supernatant and to some extent the cells (Fig. 3). A panel of transposon mutants was transformed into Pl TT01 which is normally unable to release its native Tcd into the surrounding supernatant. Oral bioassay revealed that a cosmid in which the transposon was inserted into the cosmid vector backbone did indeed generate orally toxic supernatants (Fig. S3) as it does in E. coli. Importantly the pdl1 cosmid mutant in the Pl TT01 background was again unable to produce orally toxic supernatants. Furthermore insertion into either of the Pl W14 C- or B-subunit genes also failed to produce toxic supernatants, suggesting they were essential to the Pdl1 mediated Tcd export enhancement. Interestingly, cosmid clones in which the A-subunit gene (tcdA1) was interrupted were still able to produce orally toxic supernatants. This indicated that a Pl TT01 A-subunit homologue was able to trans-complement for the cosmid Pl W14 equivalent. Conversely, the inability of the Pl TT01 B- and C-subunit homologues to trans-complement the equivalent cosmid mutants revealed that the Pl W14 Pdl1 does show some substrate specificity. As further confirmation of this we cloned pdl1 alone into the arabinose inducible expression plasmid pBAD30 for over expression in Pl TT01. Consistent with our hypothesis, this construct did not significantly increase oral toxicity of the supernatants (data not shown).

Figure 3. Insertion mutants in the c1AH10 pdl1 gene are defective in Tcd supernatant release.

Mean weight gain of cohorts of M. sexta neonates fed dilutions of washed cells or supernatants from 72 hour old cultures of E. coli containing the c1AH10 cosmid with transposon inserts in either the pdl1 gene (pdl1 KO1-mutant), white, or the pWEB cosmid vector backbone insertion (CVI-wt), shaded. Error bars represent the standard error. The more potent the toxic effect, the smaller the mean larval weight. Note the loss of toxicity at higher dilutions of the supernatants of the pdl1 knock out cosmid strain. The figures in white and black above the bars represent larval mortality numbers during the 7 day assay.

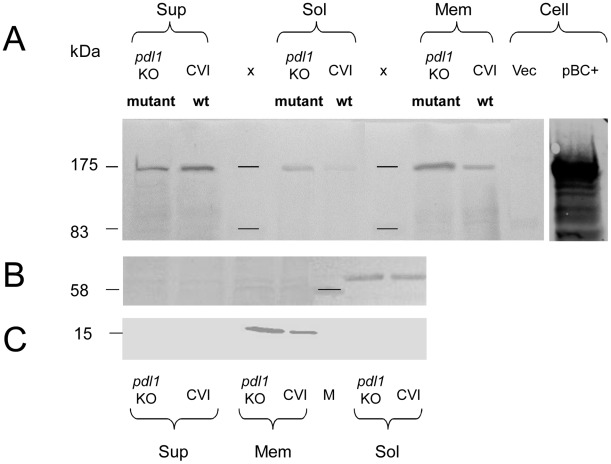

Pdl1 increases Tcd export into the supernatant

In order to understand the effect of Pdl1 on Tcd export we examined cell soluble and membrane fractions and culture supernatants for Tcd by western blotting using an anti B-subunit antibody. We compared these fractions from E. coli harbouring the wild-type (Fig. 4 - CVI) and pdl1 mutant (Fig. 4 – pdl1 KO) cosmids (Fig. 4). The wild-type cosmid strain secretes Tcd into the supernatant with very little remaining associated with the soluble fraction, which consists of cytoplasmic and periplasmic fractions. Conversely, the pdl1 mutant cosmid showed a reduction in the overall amount of Tcd secreted into the supernatant but an increase in amounts in the soluble and membrane fractions. This is despite a reduction in cell associated toxicity of the mutant (Fig. 3), suggesting that Pdl1 increases the efficiency of the normal secretion process. The soluble fraction shows the Tcd is accumulating in either in the cytoplasm and/or periplasm while the membrane fraction shows at least some is accumulating in either the inner or outer membranes. The role of Pdl1 in increasing overall export and release of Tcd was supported with a complementation assay in E. coli. We co-transformed E. coli BL21 with both the pdl1 knock out mutant cosmid and a pdl1 expression construct, pCDF-1b:pdl1. We confirmed Pdl1 expression in these strains using SDS-PAGE and confirmed that trans-complementation restored supernatant toxicity close to levels seen in the “wild-type” parental cosmid strain encoding an intact copy of the pdl1 gene (Fig. S4). Expression of Pdl1 from pCDF-1b:pdl in the absence of the tcd cosmid showed no toxicity as expected. These experiments confirmed that the transposon insertion in the pdl1 KO1-mutant cosmid was affecting the pdl1 gene only. Interestingly we also saw a slight increase in cell associated toxicity in this trans-complemented strain, consistent with the cosmid mutation studies. This indicates that Pdl1 not only increases Tcd release into the surroundings but also enhances overall expression levels.

Figure 4. Pdl1 increases TcdB release into the supernatant.

(A) Western blot analysis of culture supernatants (sup), and cellular membrane (mem) and soluble fractions, which includes cell cytosol and periplasm fractions (sol). Preparations from 24 h cultures of E. coli containing c1AH10 with transposon insertions into either the pWEB vector backbone (CVI-wt) or the pdl1 gene (pdl1 KO-mutant). X = marker and Vec = whole cell pWEB negative vector control. The presence or absence of Tcd is visualised using the antibody raised against the C-terminus of the B-subunit. Protein from an induced clone containing a B and C-subunit expression construct (pBC+) is included as a positive control. (B) An anti-β-Lactamase western blot was performed to ensure no contamination of soluble material in the membrane fraction. (C) An anti-SecG western blot was performed to ensure no contamination of membrane material in the soluble fraction.

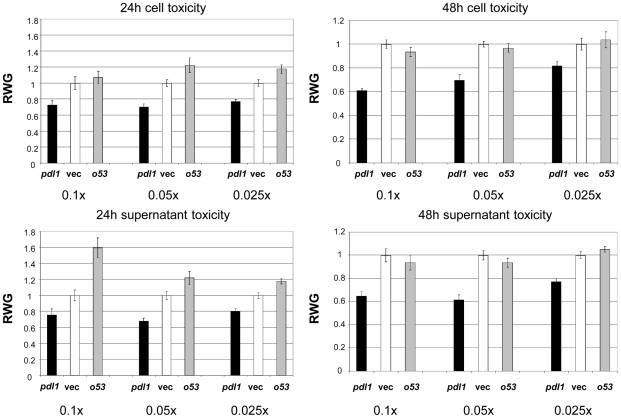

Activity and localisation of Pdl1 and Orf53

C–terminal His tagged fusions of pdl1 and the adjacent orf53 were cloned into the arabinose inducible pBAD30 expression plasmid (orf54 was not used as it appears to be translationally coupled to pdl1). These constructs were transformed into Pl W14, induced for 3, 24 and 48 hours and supernatant, membrane and soluble cell fractions prepared. The location of the His-tagged Pdl1 and Orf53 proteins were examined using western blotting with an anti-his tag antibody. Pdl1 was found in the soluble and membrane fractions for up to 2 days, but was always absent from the supernatants (Fig. S5A). Interestingly, the Orf53 protein was seen in the soluble and the membrane fractions at 3 h. The full length, unprocessed protein is seen in the soluble fraction while the majority of protein in the membrane fraction is a slightly shorter processed form, presumably with the type II signal leader removed (Fig. S5B). By 24 h the protein levels have fallen and are absent by 48 h. The oral toxicity of cells and supernatants from these same samples was tested (Fig. 5). At 24 h, over-expression of pdl1 in Pl W14 increases the level of oral toxicity of both cells and supernatants relative the vector control. Conversely over-expression of orf53 lowers toxicity of the supernatant. Interestingly by 48 h the orf53 over-expression strain returns to the normal wild-type level of oral toxicity. This correlates to the disappearance of the Orf53 protein on the western blots by two days. Pdl1 over-expression continues to increase oral toxicity even at 48 h. This supports a model whereby Pdl1 increases Tcd export and Orf53 acts antagonistically to inhibit this effect.

Figure 5. Pdl1 and Orf53 expression in strain W14 increases and decreases Tc toxin release respectively.

M. sexta oral bioassay of dilutions (0.1×, 0.05× and 0.025×) of cells and supernatants from P. luminescens W14 cultures over-expressing C-terminally his-tagged Pdl1 (pdl1) or Orf53 (o53) from the pBAD30 expression vector. Pl W14 harbouring the induced empty pBAD30 expression vector (Vec) provides a control against which the data has been normalised. Bioassays were conducted using samples taken at 24 and 48 hours post induction and the mean Relative Weight Gain (RWG) of larvae is shown, in relation to the negative controls (Vec) which therefore give a RWG of 1. Note these are the same cultures examined by western blot in Fig. S5. Each data point is derived from the mean weight of 10 neonate larvae after seven days consumption. RWG-standard error bars are also shown.

Investigating the mode of action of Pdl1

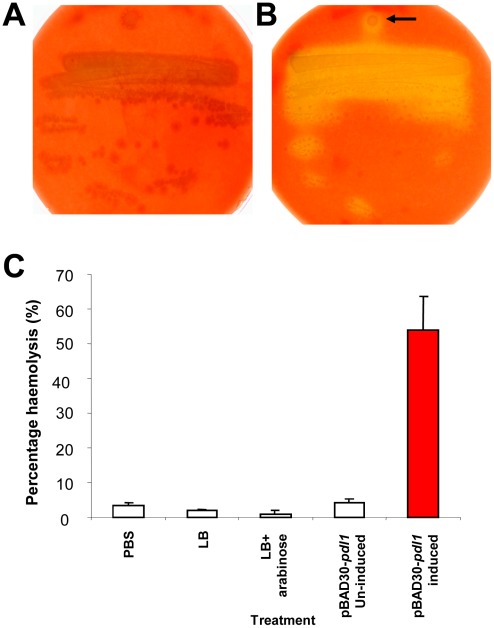

The demonstration that Pdl1 is not found in the supernatant fraction of Pl W14 cultures confirms that the increase in Tcd dependant supernatant toxicity is not the result of a continued physical association of Pdl1 with the secreted Tcd complex (Fig. S5). Protein alignments indicate that Pdl1 and Pdl2 contain putative protease and lipase like catalytic domains (Fig. S6). We therefore tested the possibility that Pdl1 might directly modify the Tcd complex in order to increase its specific activity. We mixed Tcd containing samples with lysate from the induced E. coli pBAD30-pdl1 expression strain and performed oral toxicity bioassays (Fig. S7). These experiments confirmed that Pdl1 had no effect on the activity of Tcd isolated from any of the cell compartments, suggesting it is not likely to proteolytically “activate” the complex. In order to test if Pdl1 has any measurable lipase activity we tested its ability to lyse sheep red blood cells in vitro. We did this using both standard blood-agar haemolysis plates and a liquid assay based on measuring haemoglobin release. Pdl1 was heterologously expressed using the E. coli pBAD30-pdl1 expression construct. To ensure any observed lysis was not due to the E. coli sheA dependant cryptic haemolytic activity [29], the pBAD30-pdl1 construct was first electroporated into the E. coli sheA mutant CFP201. Fig. 6 confirms that after overnight incubation, Pdl1 expressing cells show limited lysis of sheep erythrocytes consistent with lipase activity. Finally we investigated the effect of pdl1 over-expression and the co-expression of the tightly linked orf54 and orf53 upon E. coli. Pdl1 expression induced the release of specific protein species into the culture supernatant when compared to a vector only E. coli control (Fig. S8). Interestingly the most abundant of polypeptide appears to be a fragment derived from a RhsA-like protein of E. coli as well as other predicted membrane bound proteins such as the transporter MchF and the outer membrane lipoprotein PgaB. Interestingly when orf54 was co-expressed with pdl1, the abundance of the various released polypeptides decreased, and was in most cases abolished when both orf54 and orf53 were both co-expressed. This further supports our findings with Tcd secretion that Pdl1 is able to influence protein export and that the tightly linked orf54 and orf53 gene products serve to repress the function of Pdl1 in a gene dose dependant manner.

Figure 6. Pdl1 exhibits some haemolytic activity.

A weak haemolytic phenotype displayed by the E. coli heterologous pBAD30-pdl1 based expression strain. The un-induced (A) and arabinose induced (B) expression strain on agar plates containing sheep red blood cells. Note the diffuse zone of haemolysis surrounding the induced E. coli expressing Pdl1 (arrow). (C) Haemolysis of sheep red blood cells by heterologously expressed Pdl1 in a liquid assay. Controls include, PBS alone, LB medium alone, LB supplemented with 0.2% w/v arabinose and the un-induced pBAD30-pdl1 expression strain. Results are expressed as a percentage haemolysis, where 100% corresponds to the amount of haemoglobin released by complete lysis of the red blood cells using water.

Discussion

Transcript and Western blot analysis revealed that the TC subunits are under post-transcriptional regulation, and that their translation is timed with secretion and release from the cell. The TC toxin subunits encode no recognised export signal sequences and show no similarity to either two partner secretion proteins, or known auto-transported proteins. Nevertheless these large proteins are secreted from the cell and assembled into a large complex without the need for cell lysis as confirmed by the viability of the E. coli cosmid clones. This suggests that either the TC subunits are auto-transported or that they may be secreted by a chromosomally encoded system conserved in both Photorhabdus and the E. coli laboratory strains used. The mechanism of TC subunit secretion is currently under investigation in our laboratory however it is clear that the exported TC becomes localised to the membrane fraction, and is accessible to the outside of the cell, potentially located on the outer membrane. The B and C subunit proteins can both be seen to contain tyrosine-aspartic acid (YD) repeat motifs which in other proteins are involved in binding carbohydrates [30]. It is possible that the YD repeats found in the B- and C-subunits are responsible for the wall association of the TC with membrane or extracellular polysaccharide components. Another possibility is that one or more of the subunits is a lipoprotein and is attached by a lipid anchor, although they do not exhibit the usual lipidation export signal peptide. Bacterial precursor lipoproteins can be translocated across the cytoplasmic membrane by either the Sec (general secretory) or Tat (twin arginine transport) pathways [31] and then lipid modified by a lipoprotein diacylglycerol transferase on a conserved cysteine. This cysteine is located in what is known as a lipobox motif at the end of the signal peptide [32]. The TC subunits contain no such leader peptides.

Our findings show that the Pdl1 protein can enhance Tcd secretion and that products of the small tightly linked genes are able to repress this effect. Our experiments confirmed that both Pdl1 and Orf53 are located in the membrane fraction although the exact location is not clear. Unfortunately we were unable to prepare isolated inner and outer membrane fractions from Photorhabdus in order to precisely localise the tagged Pdl1 and Orf53 proteins. It should be noted that similar problems were encountered in experiments with the closely related bacteria Xenorhabdus nematophila [33]. The presence of a type II Sec-dependant secretion leader on Orf53 does suggest that it can at least reach the periplasmic space, and indeed our experiments show both intact and processed forms consistent with cleavage of the signal peptide. PSORT analysis of the protein sequence gives a strong prediction for its localisation in the periplasmic space (certainty value = 0.930).

Results presented here suggest that the Pdl1 protein does not associate with or modify the Toxin Complex directly in order to increase its specific activity. Rather our data are consistent with a role in the enhancement of secretion. The over-expression of Pdl1 in Pl W14 increases the overall levels of both supernatant and cell contact dependant toxicity. One possible model infers that translation is coupled to export, with Pdl1 increasing the efficiency of secretion, leading to an overall increase in TC production. In this model, as cell surface binding sites become limited, then excess toxin is shed into the surrounding medium. Pdl1 may interact with the Tcd secretion mechanism on the cytoplasmic membrane during export. In this model, the Orf53 molecules would antagonise the activity of Pdl1 by interactions on the periplasmic face of the inner membrane. While we confirm lipase activity of Pdl1, the predicted presence of a serine protease catalytic motif does suggest that while proteolytic activity may not be involved in “activation” of the TC, it could still play a role in enhancing secretion.

Experiments in which cosmid mutants were transformed into strain TT01 suggest that the Pdl1 mediated release is dependent upon the BC sub-complex and is independent of the A-subunit. It should be noted that C-subunits belong to a much larger family that includes the Recombination Hot Spot genes (Rhs) of E. coli. These genes have an unusual structure with conserved N-termini, a highly conserved central core region and variable C-terminal “tails” [30], [34]. In the case of the C-subunit proteins we know the variable C-terminal domains encode toxic effectors [9]. The N-terminal domain of RhsA has been shown to be involved in the biosynthesis and export of capsular polysaccharide in E. coli although the exact mechanism remains cryptic [35]. Interestingly, Rhs-core like genes are often tightly linked to vgrG genes which in some cases have been shown to be contact dependant cytotoxins exported via type VI secretion machinery, temping the speculation of an equivalent toxin secretion and anchoring role [36].

An examination of the full genome sequence of P. luminescens TT01 shows only a single pdl homologue unlinked to any tc genes. Interestingly this is however closely linked to a putative type III effector toxin gene, plu3163 (HopT1-2 homologue). The emerging human pathogen P. asymbiotica can however be seen to contain several genomic islands (GIs) containing repeats of pdl-orf54 like genes. When cloned on cosmids, three of these pdl-GIs have been shown to be toxic to insects and nematodes [37]. Insertional mutagenesis of a cosmid containing the pdl-GI_2 region (Fig. S9A) confirmed that knock-out of either the putative toxin gene (a vgrG homologue) or two of the pdl homologues significantly reduced toxicity of the bacterial cultures [37]. When compared to genomic sequences in the public databases pdl-like genes may be seen in other pathogenic bacterial genera including Vibrio and Pseudomonas [38]–[39]. In many genomes we can see tight linkage between type VI secretion operons and pdl-orf54 homologue gene pairs, suggesting they also play a role in these secretion systems (Fig. S9B). Taken together, these findings suggest that Pdl homologues may represent a novel general mechanism for enhancing secretion of toxins from Gram-negative bacteria.

Supporting Information

Cosmid gene transcription is similar to that in the parent strain Pl W14. Comparisons of the transcription of genes present on c1AH10 in E. coli and in the original strain P. luminescens W14. RT-PCR amplification from total RNA prepared from equivalent cell numbers at different points in the growth curve in vitro at 30°C shaking in LB medium. Note the functional Tcd subunit genes are in dotted boxes and the pdl1 is boxed in solid outline. The key to the gene location on the cosmid is shown above. RNA samples were taken at early exponential (OD600 = 0.2, c.a. 2 h), late exponential (OD600 = 1.0, c.a. 5 h), stationary phase (OD600 = 2.0, c.a. 8 h) and 72 hours into growth respectively. The presence of oral toxicity in the supernatants is indicated, with (−) meaning no toxicity and a range of toxicity from partial (+) to maximal (++++). The star indicates the expression of pdl1 which peaks at the time of TC release into the supernatant.

(TIF)

TcdB1 expression in Pl W14 and the cosmid clone. Expression was tracked using an anti-peptide raised against a peptide located in the C-terminal region of the B-subunit TcdB1 (aa856-YSSSEEKPFSPPNDC-aa869). (A) A qualitative comparison of culture supernatants of wild type Pl W14 and a strain in which tcdA and tcdB have been deleted (D-). The absence of cross reactivity in the tcdAB KO strain samples confirmed that the anti-peptide antibody used is specific to the TcdB1 B-subunit. The pBC+ lane represents a positive control of whole cells of an induced E. coli pBAD30 based heterologous tcdB1-tccC1 expression strain. (B) A qualitative comparison of the sub-cellular location of TcdB1 in Pl W14 and E. coli containing c1AH10 (cos). Sup = supernatants; Sol = cytoplasmic+periplasmic fractions; Mem = membrane fractions. Samples were prepared from cultures generating orally toxic supernatants after 72 hrs growth in vitro at 30°C (* indicates confirmation of oral toxicity by bioassay).

(TIF)

Oral toxicity of cosmid transposon mutants in Pl TT01. (A) Map of cosmid c1AH10 showing transposon insertion points tested for supernatant oral toxicity when transformed into P. luminescens TT01. Filled inverted triangles represent transposon insertion points that maintained toxicity (T = toxic), while those which abolished toxicity are shown as open triangles (NT = not toxic). (B) Mean relative weight gain (RWG) of cohorts of M. sexta neonates fed supernatants from 72 hrs cultures of Pl TT01 containing the various cosmid mutants. Note the data has been normalised to that from the TT01 strain containing the c1AH10 with a transposon insertion into the pWEB vector backbone (CVI) which produced the maximum toxicity. Error bars represent the standard error. Note the black bars show a failure of the pdl1 knock out mutants to secrete active toxin and the hatched bars indicate that both the B and C-subunit (tcdB1 and tccC5) genes are also required for release of toxin. Insertion into the A-subunit gene (tcdA1) remained fully toxic, so must be able to be trans-complemented by chromosomal A-subunit homologues.

(TIF)

Trans-complementation of the pdl -knock out cosmid strain restores the Tcd release phenotype. Mean weight gain of cohorts of M. sexta neonates (n = 12) fed with whole cultures, supernatants or cells from 72 hour old 28°C grown cultures of E. coli containing the CVI-wt cosmid (with transposon inserts in the pWEB backbone), the pdl1 KO1-mutant cosmid (with transposon inserts in the pdl1 gene), both the pdl1 KO1-mutant cosmid and the pCDF-1b:pdl1 vector (expressing Pdl1), and the pCDF-1b:pdl1 vector alone. Error bars represent the standard error. The more potent the toxic effect, the smaller the mean larval weight. Note the restoration of toxic activity in the supernatants pdl1 KO1-mutant strain expressing trans-complemented Pdl1.

(TIF)

In Pl W14, Pdl1 and Orf53 are not released into the supernatant. Western blots of membrane (m), soluble cytoplasm+periplasm (sol) and supernatant (s) fractions from Pl W14 over-expressing C-terminally his-tagged Pdl1 (A) and Orf53 (B) from the arabinose inducible pBAD30 expression vector. Samples were taken at 3, 24 and 48 hours and continued arabinose induction was maintained throughout the incubation period. The native Shine-Dalgarno sequences are included in these constructs. The two arrows (B) indicate the presumed processed and full length forms of Orf53. Size markers are also shown (x). An anti-β-lactamase western blot (Anti-BLA) was performed as a control for loading amounts and the quality of the fractionation for both expression constructs.

(TIF)

Pdl has potential protease and lipase domains. Alignment of the predicted amino acid sequences of Pl W14 Pdl1 and Pdl2 (Genbank AY144119), with predicted products of the A. oryzae mdlB gene (Genbank D85895) and a V. cholerae hypothetical open reading frame, VC1418 (Genbank AE004220). The presence of the presumptive serine protease-like catalytic triad (S, D and H) is highlighted (red) alongside the conserved pentapeptide GHSXG (yellow) common to lipases and lipoprotein lipases.

(TIF)

Pdl1 has no direct effect on the activity of Tcd. Mean weight gain of cohorts of M. sexta neonates (n = 10) fed different Tcd containing cell fractions (soluble, washed whole cells or supernatants) which had been pre-incubated for 1 h at 28°C with sonicated cell extracts from either an induced E. coli pBAD30-pdl1 expression construct (Pdl1) or an E. coli pBAD30 negative control (pBAD30). The Tcd fractions were isolated from the E. coli pdl1 knock out cosmid strain (pdl1-KO). We also used E. coli pWEB fractions as a further negative control (pWEB). Standard error bars are shown. The more potent the toxic effect, the smaller the mean larval weight. Note the presence of added Pdl1 does not increase toxic activity of Tcd from any fraction. Data from a 7 day assay.

(TIF)

The effects of Pdl1 and Orf53 over-expression on native protein release in E. coli . The effect of pdl1, pdl1+orf54 and pdl+orf54+orf53 pBAD30 expression constructs on supernatant proteins released by the recombinant E. coli. All genes have their native Shine-Dalgarno sequences. Size markers are also shown (x). Note Pdl1 induces the release of several specific protein species (boxed). The inclusion of orf54 and orf53 (which are homologues of one another) reduce this effect in an additive manner. Putative MALDI-ToF identification of several of these E. coli protein species are indicated.

(TIF)

Pdl homologues are associated with other toxin secretion genes in diverse bacteria. (A) A pdl-orf54 island of P. asymbiotica ATCC43949 identified using RVA screening exhibiting insect toxicity on injection. Colour coding identifies homologous genes. Genbank locus tag numbers are given. The pdl and vgrG homologues were shown to be responsible for the toxicity of the Pa pdl-GI_2 virulence island were mapped by transposon mutagenesis (red inverted triangles) (B) pdl-orf54 homologues are often tightly linked to other toxin secretion systems in diverse pathogens such as type VI secretion systems in Vibrio and Pseudomonas.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Chris Apark for maintenance of the M. sexta.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

This work was funded by European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement no 23328 and also from the BBSRC grant (number BB/E021328/1. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Waterfield NR, Ciche T, Clarke D. Photorhabdus and a host of hosts. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2009;63:557–574. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waterfield NR, Bowen DJ, Fetherston JD, Perry RD, ffrench-Constant RH. The tc genes of Photorhabdus: a growing family. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:185–191. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)01978-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waterfield N, Hares M, Yang G, Dowling A, ffrench-Constant R. Potentiation and cellular phenotypes of the insecticidal Toxin complexes of Photorhabdus bacteria. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:373–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowen D, Rocheleau TA, Blackburn M, Andreev O, Golubeva E, et al. Insecticidal toxins from the bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens. Science. 1998;280:2129–2132. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5372.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackburn M, Golubeva E, Bowen D, ffrench-Constant RH. A novel insecticidal toxin from Photorhabdus luminescens: histopathological effects of Toxin complex A (Tca) on the midgut of Manduca sexta. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3036–3041. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.8.3036-3041.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ffrench-Constant R, Waterfield N. An ABC guide to the bacterial toxin complexes. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2006;58:169–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee SC, Stoilova-McPhie S, Baxter L, Fulop V, Henderson J, et al. Structural characterisation of the insecticidal toxin XptA1, reveals a 1.15 MDa tetramer with a cage-like structure. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:1558–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheets JJ, Hey TD, Fencil KJ, Burton SL, Ni W, et al. Insecticidal Toxin Complex Proteins from Xenorhabdus nematophilus: STRUCTURE AND PORE FORMATION. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:22742–22749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.227009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang AE, Schmidt G, Schlosser A, Hey TD, Larrinua IM, et al. Photorhabdus luminescens toxins ADP-ribosylate actin and RhoA to force actin clustering. Science. 2010;327:1139–1142. doi: 10.1126/science.1184557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hares MC, Hinchliffe SJ, Strong PC, Eleftherianos I, Dowling AJ, et al. The Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Yersinia pestis toxin complex is active against cultured mammalian cells. Microbiology. 2008;154:3503–3517. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/018440-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tennant SM, Skinner NA, Joe A, Robins-Browne RM. Homologues of insecticidal toxin complex genes in Yersinia enterocolitica biotype 1A and their contribution to virulence. Infect Immun. 2005;73:6860–6867. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6860-6867.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sergeant M, Jarrett P, Ousley M, Morgan JA. Interactions of insecticidal toxin gene products from Xenorhabdus nematophilus PMFI296. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:3344–3349. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.6.3344-3349.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waterfield N, Dowling A, Sharma S, Daborn PJ, Potter U, et al. Oral toxicity of Photorhabdus luminescens W14 toxin complexes in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:5017–5024. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.11.5017-5024.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu D, Burton S, Glancy T, Li ZS, Hampton R, et al. Insect resistance conferred by 283-kDa Photorhabdus luminescens protein TcdA in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1307–1313. doi: 10.1038/nbt866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erickson DL, Waterfield NR, Vadyvaloo V, Long D, Fischer ER, et al. Acute oral toxicity of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis to fleas: implications for the evolution of vector-borne transmission of plague. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:2658–2666. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao R, Han R, Qiu X, Yan X, Cao L, et al. Cloning and heterologous expression of insecticidal-protein-encoding genes from Photorhabdus luminescens TT01 in Enterobacter cloacae for termite control. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:7219–7226. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00977-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowen DJ. Characterization of a high molecular weight insecticidal protein complex produced by the entomothogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens [PhD] Madison (Wisconsin): University of Wisconsin-Madison; 1995. 282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waterfield NR, Daborn PJ, ffrench-Constant RH. Genomic islands in Photorhabdus. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:541–545. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(02)02463-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silva CP, Waterfield NR, Daborn PJ, Dean P, Chilver T, et al. Bacterial infection of a model insect: Photorhabdus luminescens and Manduca sexta. Cell Microbiol. 2002;6:329–339. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waterfield NR, Daborn PJ, ffrench-Constant RH. Insect pathogenicity islands in the insect pathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus. Physiol Entomol. 2004;29:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waterfield N, Kamita SG, Hammock BD, ffrench-Constant R. The Photorhabdus Pir toxins are similar to a developmentally regulated insect protein but show no juvenile hormone esterase activity. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;245:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daborn PJ, Waterfield N, Silva CP, Au CPY, Sharma S, et al. A single Photorhabdus gene makes caterpillars floppy (mcf) allows Esherichia coli to persist within and kill insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10742–10747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102068099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowe GE, Welch RA. Assays of hemolytic toxins. Methods Enzymol. 1994;235:657–667. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerrard JG, Joyce SA, Clarke DJ, ffrench-Constant RH, Nimmo GR, et al. Nematode symbiont for Photorhabdus asymbiotica. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1562–1564. doi: 10.3201/eid1210.060464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peat SM, Ffrench-Constant RH, Waterfield NR, Marokhazi J, Fodor A, et al. A robust phylogenetic framework for the bacterial genus Photorhabdus and its use in studying the evolution and maintenance of bioluminescence: a case for 16S, gyrB, and glnA. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2010;57:728–740. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marokhazi J, Waterfield N, LeGoff G, Feil E, Stabler R, et al. Using a DNA microarray to investigate the distribution of insect virulence factors in strains of photorhabdus bacteria. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:4648–4656. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.15.4648-4656.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duchaud E, Rusniok C, Frangeul L, Buchrieser C, Givaudan A, et al. The genome sequence of the entomopathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1307–1313. doi: 10.1038/nbt886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daborn PJ, Waterfield N, Blight MA, Ffrench-Constant RH. Measuring virulence factor expression by the pathogenic bacterium Photorhabdus luminescens in culture and during insect infection. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:5834–5839. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.20.5834-5839.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.del Castillo FJ, Leal SC, Moreno F, del Castillo I. The Escherichia coli K-12 sheA gene encodes a 34-kDa secreted haemolysin. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:107–115. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4391813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill CW, Sandt CH, Vlazny DA. Rhs elements of Escherichia coli: a family of genetic composites each encoding a large mosaic protein. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:865–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson BJ, Widdick DA, Hicks MG, Chandra G, Sutcliffe IC, et al. Investigating lipoprotein biogenesis and function in the model Gram-positive bacterium Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol Microbiol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07261.x. E-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hutchings MI, Palmer T, Harrington DJ, Sutcliffe IC. Lipoprotein biogenesis in Gram-positive bacteria: knowing when to hold 'em, knowing when to fold 'em. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cowles CE, Goodrich-Blair H. Characterization of a lipoprotein, NilC, required by Xenorhabdus nematophila for mutualism with its nematode host. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54:464–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao S, Sandt CH, Feulner G, Vlazny DA, Gray JA, et al. Rhs elements of Escherichia coli K-12: complex composites of shared and unique components that have different evolutionary histories. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2799–2808. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.10.2799-2808.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McNulty C, Thompson J, Barrett B, Lord L, Andersen C, et al. The cell surface expression of group 2 capsular polysaccharides in Escherichia coli: the role of KpsD, RhsA and a multi-protein complex at the pole of the cell. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:907–922. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.05010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pukatzki S, Ma AT, Revel AT, Sturtevant D, Mekalanos JJ. Type VI secretion system translocates a phage tail spike-like protein into target cells where it cross-links actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15508–15513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706532104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waterfield NR, Sanchez-Contreras M, Eleftherianos I, Dowling A, Wilkinson P, et al. Rapid Virulence Annotation (RVA): identification of virulence factors using a bacterial genome library and multiple invertebrate hosts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15967–15972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711114105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pukatzki S, Ma AT, Sturtevant D, Krastins B, Sarracino D, et al. Identification of a conserved bacterial protein secretion system in Vibrio cholerae using the Dictyostelium host model system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1528–1533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510322103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mougous JD, Cuff ME, Raunser S, Shen A, Zhou M, et al. A virulence locus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a protein secretion apparatus. Science. 2006;312:1526–1530. doi: 10.1126/science.1128393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cosmid gene transcription is similar to that in the parent strain Pl W14. Comparisons of the transcription of genes present on c1AH10 in E. coli and in the original strain P. luminescens W14. RT-PCR amplification from total RNA prepared from equivalent cell numbers at different points in the growth curve in vitro at 30°C shaking in LB medium. Note the functional Tcd subunit genes are in dotted boxes and the pdl1 is boxed in solid outline. The key to the gene location on the cosmid is shown above. RNA samples were taken at early exponential (OD600 = 0.2, c.a. 2 h), late exponential (OD600 = 1.0, c.a. 5 h), stationary phase (OD600 = 2.0, c.a. 8 h) and 72 hours into growth respectively. The presence of oral toxicity in the supernatants is indicated, with (−) meaning no toxicity and a range of toxicity from partial (+) to maximal (++++). The star indicates the expression of pdl1 which peaks at the time of TC release into the supernatant.

(TIF)

TcdB1 expression in Pl W14 and the cosmid clone. Expression was tracked using an anti-peptide raised against a peptide located in the C-terminal region of the B-subunit TcdB1 (aa856-YSSSEEKPFSPPNDC-aa869). (A) A qualitative comparison of culture supernatants of wild type Pl W14 and a strain in which tcdA and tcdB have been deleted (D-). The absence of cross reactivity in the tcdAB KO strain samples confirmed that the anti-peptide antibody used is specific to the TcdB1 B-subunit. The pBC+ lane represents a positive control of whole cells of an induced E. coli pBAD30 based heterologous tcdB1-tccC1 expression strain. (B) A qualitative comparison of the sub-cellular location of TcdB1 in Pl W14 and E. coli containing c1AH10 (cos). Sup = supernatants; Sol = cytoplasmic+periplasmic fractions; Mem = membrane fractions. Samples were prepared from cultures generating orally toxic supernatants after 72 hrs growth in vitro at 30°C (* indicates confirmation of oral toxicity by bioassay).

(TIF)

Oral toxicity of cosmid transposon mutants in Pl TT01. (A) Map of cosmid c1AH10 showing transposon insertion points tested for supernatant oral toxicity when transformed into P. luminescens TT01. Filled inverted triangles represent transposon insertion points that maintained toxicity (T = toxic), while those which abolished toxicity are shown as open triangles (NT = not toxic). (B) Mean relative weight gain (RWG) of cohorts of M. sexta neonates fed supernatants from 72 hrs cultures of Pl TT01 containing the various cosmid mutants. Note the data has been normalised to that from the TT01 strain containing the c1AH10 with a transposon insertion into the pWEB vector backbone (CVI) which produced the maximum toxicity. Error bars represent the standard error. Note the black bars show a failure of the pdl1 knock out mutants to secrete active toxin and the hatched bars indicate that both the B and C-subunit (tcdB1 and tccC5) genes are also required for release of toxin. Insertion into the A-subunit gene (tcdA1) remained fully toxic, so must be able to be trans-complemented by chromosomal A-subunit homologues.

(TIF)

Trans-complementation of the pdl -knock out cosmid strain restores the Tcd release phenotype. Mean weight gain of cohorts of M. sexta neonates (n = 12) fed with whole cultures, supernatants or cells from 72 hour old 28°C grown cultures of E. coli containing the CVI-wt cosmid (with transposon inserts in the pWEB backbone), the pdl1 KO1-mutant cosmid (with transposon inserts in the pdl1 gene), both the pdl1 KO1-mutant cosmid and the pCDF-1b:pdl1 vector (expressing Pdl1), and the pCDF-1b:pdl1 vector alone. Error bars represent the standard error. The more potent the toxic effect, the smaller the mean larval weight. Note the restoration of toxic activity in the supernatants pdl1 KO1-mutant strain expressing trans-complemented Pdl1.

(TIF)

In Pl W14, Pdl1 and Orf53 are not released into the supernatant. Western blots of membrane (m), soluble cytoplasm+periplasm (sol) and supernatant (s) fractions from Pl W14 over-expressing C-terminally his-tagged Pdl1 (A) and Orf53 (B) from the arabinose inducible pBAD30 expression vector. Samples were taken at 3, 24 and 48 hours and continued arabinose induction was maintained throughout the incubation period. The native Shine-Dalgarno sequences are included in these constructs. The two arrows (B) indicate the presumed processed and full length forms of Orf53. Size markers are also shown (x). An anti-β-lactamase western blot (Anti-BLA) was performed as a control for loading amounts and the quality of the fractionation for both expression constructs.

(TIF)

Pdl has potential protease and lipase domains. Alignment of the predicted amino acid sequences of Pl W14 Pdl1 and Pdl2 (Genbank AY144119), with predicted products of the A. oryzae mdlB gene (Genbank D85895) and a V. cholerae hypothetical open reading frame, VC1418 (Genbank AE004220). The presence of the presumptive serine protease-like catalytic triad (S, D and H) is highlighted (red) alongside the conserved pentapeptide GHSXG (yellow) common to lipases and lipoprotein lipases.

(TIF)

Pdl1 has no direct effect on the activity of Tcd. Mean weight gain of cohorts of M. sexta neonates (n = 10) fed different Tcd containing cell fractions (soluble, washed whole cells or supernatants) which had been pre-incubated for 1 h at 28°C with sonicated cell extracts from either an induced E. coli pBAD30-pdl1 expression construct (Pdl1) or an E. coli pBAD30 negative control (pBAD30). The Tcd fractions were isolated from the E. coli pdl1 knock out cosmid strain (pdl1-KO). We also used E. coli pWEB fractions as a further negative control (pWEB). Standard error bars are shown. The more potent the toxic effect, the smaller the mean larval weight. Note the presence of added Pdl1 does not increase toxic activity of Tcd from any fraction. Data from a 7 day assay.

(TIF)

The effects of Pdl1 and Orf53 over-expression on native protein release in E. coli . The effect of pdl1, pdl1+orf54 and pdl+orf54+orf53 pBAD30 expression constructs on supernatant proteins released by the recombinant E. coli. All genes have their native Shine-Dalgarno sequences. Size markers are also shown (x). Note Pdl1 induces the release of several specific protein species (boxed). The inclusion of orf54 and orf53 (which are homologues of one another) reduce this effect in an additive manner. Putative MALDI-ToF identification of several of these E. coli protein species are indicated.

(TIF)

Pdl homologues are associated with other toxin secretion genes in diverse bacteria. (A) A pdl-orf54 island of P. asymbiotica ATCC43949 identified using RVA screening exhibiting insect toxicity on injection. Colour coding identifies homologous genes. Genbank locus tag numbers are given. The pdl and vgrG homologues were shown to be responsible for the toxicity of the Pa pdl-GI_2 virulence island were mapped by transposon mutagenesis (red inverted triangles) (B) pdl-orf54 homologues are often tightly linked to other toxin secretion systems in diverse pathogens such as type VI secretion systems in Vibrio and Pseudomonas.

(TIF)