Abstract

Background

There are limited data on the epidemiology of allergic disorders in Saudi Arabia. Such data are needed for, amongst other things, helping to plan service provision at a time when there is considerable investment taking place in national healthcare development. We sought to estimate the prevalence of atopic eczema, allergic rhinitis and asthma in primary school children in Madinah, Saudi Arabia.

Methods and Findings

We conducted a two-stage cross-sectional survey of schoolchildren in Madinah. Children were recruited from 38 randomly selected schools. Questionnaires were sent to the parents of all 6,139 6–8 year old children in these schools. These parental-completed questionnaires incorporated questions from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC), which had previously been validated for use in Arab populations. We undertook descriptive analyses, using the Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) to calculate 95% confidence intervals. The overall response rate was 85.9% (n = 5,188), 84.6% for girls and 86.2% for boys, respectively. Overall, parents reported symptoms suggestive of a history of eczema in 10.3% (95%CI 9.4, 11.4), rhinitis in 24.2% (95%CI 22.3, 26.2) and asthma in 23.6% (95%CI 21.3, 26.0) of children. Overall, 41.7% (95%CI 39.1, 44.4) of children had symptoms suggestive of at least one allergic disorder, with a substantial minority manifesting symptoms indicative of co-morbid allergic disease. Comparison of these symptom-based prevalence estimates with reports of clinician-diagnosed disease suggested that the majority of children with eczema and asthma had been diagnosed, but only a minority (17.4%) of children had been diagnosed with rhinitis. International comparisons indicated that children in Madinah have amongst the highest prevalence of allergic problems in the world.

Conclusions

Symptoms indicative of allergic disease are very common in primary school-aged children in Madinah, Saudi Arabia, with figures comparable to the highest risk regions in the world.

Introduction

The incidence and prevalence of allergic disorders has increased considerably in recent decades, so much so that allergic disorders are now amongst the most common chronic disorders of childhood [1]. Whilst major international epidemiological studies such as the International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Childhood (ISAAC) [2]–[3] and the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS) [4] have greatly increased our understanding of allergic disease prevalence in many parts of the world, there remains a dearth of epidemiological data in relation to much of the Middle East, including Saudi Arabia. [5]. This is problematic, because it hampers understanding of these conditions in Saudi children, making planning of appropriate health provision difficult.

The limited available data in Saudi Arabia on allergic disorders are largely confined to asthma, with studies indicating that the prevalence in Saudi Arabia varies anywhere between 8–15% in children [6]–[7]. These studies are, however, relatively small-scale, are affected by methodological limitations such as the failure to make due adjustments for clustered sampling when estimating confidence intervals (CI), and are furthermore now somewhat dated.

We report on a large regional survey, which aimed to determine the prevalence of asthma and other allergic diseases among Saudi children using the validated Arabic version of the ISAAC questionnaire [8].

Methods

Ethics Statement

There is no health ethics committee for school-based research in the Madinah region. Permission to undertake this research was however obtained from the education authorities in Madinah (General Directors) and school health departments in the Ministry of Education, Riyadh and from the respective school head teachers. Parents were asked to give their signed informed consent. All data had identifiers removed to prevent the risk of a breach of confidentiality.

Design

We conducted a two stage cross-sectional survey of the parents of primary school students aged 6–8 years in Madinah, which is one of the largest provinces in Saudi Arabia, in April 2009. The two stages involved sampling and recruiting schools and then children from within these schools. The methods were largely based on those used in the ISAAC studies (see: http://isaac.auckland.ac.nz/index.html for further details) and piloted by the research team in Madinah, Saudi Arabia in 2008.

Setting

Madinah is a city in the west of Saudi Arabia It has an area of 589 Km2 and is about 190 Km from the Red Sea coast. It has a population of ∼1.5 million people from a total Saudi population of 21.4 million [9].

Recruitment of Schools

A list of all government and private primary schools in Madinah was obtained from the General Directorate of Education in the Madinah region (i.e. both boys’ and girls’ departments respectively); these primary schools were responsible for providing education for children aged 6–12 years. Schools were then stratified (according to the geographical area and sex) and a random sample of 38 schools (9 schools for girls and 29 for boys) was approached. We invited the schools to participate with a letter of explanation to the head teachers outlining the purpose of the study and the procedures that were to be employed.

Recruitment of Children

There were 33,270 male students (59.7%) and 22,412 female students (40.3%) aged 6–8years old in primary schools in Madinah (i.e. a total of 55,682 students). All students aged 6–8 years who were long-term residents in Madinah (i.e. for at least two years) and enrolled in the selected schools were eligible to participate. The parents of these children were sent, via the school, a letter explaining the rationale for the study and what it entailed, a consent form and a questionnaire, which they were invited to complete and return this to the class teacher. There were no reminders issued to non-responders.

Questionnaire

Permission was obtained from Oman University to use the Arabic version of the validated ISAAC questionnaire [8]. The questionnaire was in two parts. Part one was the Arabic translated version of the core ISAAC questionnaire, which comprised 21 questions posed to parents relating to the prevalence of eczema, rhinitis and asthma in their children; the information requested included: 1) parental reports of symptoms of allergic diseases; 2) parental reports of diagnosed allergic diseases; and 3) parental reports of current symptoms of allergic disorders. The second part of the questionnaire contained questions relevant to possible environmental risk factors for the development of these conditions. These environmental questions were modified slightly to ensure that all questions were relevant to the Saudi context, for example, relating to housing conditions, exposure to animals and presence of animals at home, number of siblings and other people living in the house, and parental smoking. Data on these environmental risk factors will be reported separately in due course.

Data Analysis

Data were coded, checked, entered into an Excel spreadsheet (version 2003) and then analysed using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) (Version 16). Descriptive analysis was undertaken, expressing categorical data as numbers and percentages; to account for the two-stage sampling, Generalised Estimating Equations (GEE) were used to fit random effects logistic models to estimate and calculate 95% CI for prevalence; continuous data were summarised using means and standard deviations [10]. We report separate prevalence estimates for both males and females; we also calculated overall estimates in children to allow comparison with international data.

Results

Recruitment of Schools and Charactertistics

All 38 schools approached agreed to participate. In keeping with the wider preponderance of government-funded schools, 36/38 (94.7%) of these schools were government funded.

Parental Response Rate

A total of 6,139 questionnaires were distributed for parental completion, of which 5,188 (85.9%) completed questionnaires were returned to the school and collected from the schools by the research team. Replies were received from the parents of 3585/4159 (86.2%) boys and 1603/1894 (84.6%) girls, respectively. Missing values for any question did not exceed 10.0% for any question.

Characteristics of Respondents

The percentages of children in the age ranges 6–7, 7–8 and 8–9 years were: 16%, 36% and 48% for boys; and 17%, 30% and 52% for girls. The majority of the study population were Saudi nationals (80%); Table 1 summarises data on the characteristics of the families of participating children.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population.

| Variable | Males (n = 3585) | Females (n = 1603) | Total (n = 5188) |

| Father’s age, years: mean (SD) | 43.6 (8.6) | 44.4 (8.4) | 43.8 (8.6) |

| Mother’s age, years: mean (SD) | 35.2 (6.2) | 36.2 (6.0) | 35.5 (6.1) |

| Father’s education (highest qualification) n (%) | |||

| None | 260 (7.3%) | 153 (9.5%) | 413 (7.9%) |

| General education | 1966 (54.8%) | 922 (57.5%) | 2888 (55.7%) |

| Higher education | 1200 (33.5%) | 459 (28.6%) | 1659 (31.9%) |

| Missing | 159 (4.4%) | 69 (4.3%) | 228 (4.4%) |

| Mother’s education (highest qualification) n (%) | |||

| None | 381 (10.6%) | 208 (12.9%) | 589 (11.4%) |

| General education | 2035 (56.8%) | 963 (60.1%) | 2998 (57.8%) |

| Higher education | 1057 (29.5%) | 364 (22.7%) | 1421 (27.4%) |

| Missing | 112 (3.12%) | 68 (4.2%) | 180 (3.5%) |

| Exposure to farm animals during pregnancy with this child? n (%) | |||

| Yes | 155 (4.5%) | 63 (3.9%) | 218 (4.2%) |

| No | 3266 (95.5%) | 1467 (91.5%) | 4733 (91.2%) |

| Missing | 164 (4.6%) | 73 (4.6%) | 237 (4.6%) |

| Was the child born in Madinah? n (%) | |||

| Yes | 2999 (83.7%) | 1318 (82.2%) | 4317 (83.2%) |

| No | 521 (14.5%) | 257 (16.0%) | 778 (15.0%) |

| Missing | 65 (1.8%) | 28 (1.7%) | 93 (1.8%) |

| Child’s birth weight in kg: mean (SD) | 2.94 (0.64) | 2.91 (0.66) | 2.93 (0.64) |

| Did the mother breast feed? n (%) | |||

| Yes | 2935 (81.9%) | 1319 (82.3%) | 4254 (82.0%) |

| No | 567 (15.8%) | 240 (15.0%) | 807 (15.6%) |

| Missing | 83 (2.3%) | 44 (2.7%) | 127 (2.4%) |

| Birth order n (%) | |||

| First child | 626 (17.5%) | 226 (14.1%) | 852 (16.4%) |

| Second child | 587 (16.4%) | 292 (18.2%) | 879 (17.0%) |

| Third or greater | 2296 (64.0%) | 1034 (64.5%) | 3330 (64.2%) |

| Missing | 76 (2.1%) | 51 (3.2%) | 127 (2.4%) |

| How many years has the child lived in Madinah? n (%) | |||

| More than one year | 3354 (93.6%) | 1487 (92.8%) | 4841 (93.3%) |

| One year or less | 47 (1.3%) | 19 (1.2%) | 66 (1.3%) |

| Missing | 184 (5.1%) | 97 (6.1%) | 281 (5.4%) |

| Does the father smoke? n (%) | |||

| Yes | 828 (23.1%) | 405 (25.3%) | 1233 (23.8%) |

| No | 2695 (75.2%) | 1164 (72.6%) | 3859 (74.4%) |

| Missing | 62 (1.7%) | 34 (2.1%) | 96 (1.9%) |

| Does the mother smoke? n (%) | |||

| Yes | 30 (0.8%) | 13 (0.8%) | 43 (0.8%) |

| No | 3483 (97.2%) | 1562 (97.4%) | 5045 (97.2%) |

| Missing | 72 (2.0%) | 28 (1.8%) | 100 (2.0%) |

| Did the mother smoke in the child’s 1st year of the life? n (%) | |||

| Yes | 24 (0.6%) | 14 (0.9%) | 38 (0.7%) |

| No | 3491 (97.4%) | 1552 (96.8%) | 5043 (97.2%) |

| Missing | 70 (2.0%) | 37 (2.3%) | 107 (2.1%) |

| Number of smokers in the household n (%) | |||

| No smokers | 2675 (74.6%) | 1156 (72.1%) | 3831 (73.8%) |

| one or more smokers | 838 (23.4%) | 410 (25.6%) | 1248 (24.1%) |

| Missing | 72 (2.0%) | 37 (2.3%) | 109 (2.1%) |

| Was there a cat at home in the child’s 1st year of life? n (%) | |||

| Yes | 160 (4.5%) | 67 (4.2%) | 227 (4.4%) |

| No | 3345 (93.3%) | 1496 (93.3%) | 4841 (93.3%) |

| Missing | 80(2.2%) | 40(2.5%) | 120 (2.3%) |

| Was there a cat at home in the last 12 months? n (%) | |||

| Yes | 224 (6.3%) | 91 (5.7%) | 315 (6.1%) |

| No | 3292 (91.8%) | 1470 (91.7%) | 4762 (91.8%) |

| Missing | 69 (1.9%) | 42 (2.6%) | 111 (2.2%) |

| Did the child have antibiotics in the 1st year? n (%) | |||

| Yes | 2002 (55.8%) | 926 (57.8%) | 2928 (56.4%) |

| No | 1384 (38.6%) | 597 (37.2%) | 1981 (38.2%) |

| Missing | 199 (5.6%) | 80 (5.0%) | 279 (5.4%) |

| Did the child have paracetamol during the first year of life? n (%) | |||

| Yes | 3011 (84%) | 1232 (77.0%) | 4243 (82.0%) |

| No | 441 (12.3%) | 305 (19.0%) | 746 (14.4%) |

| Missing | 133 (3.7%) | 66 (4.1%) | 199 (3.8%) |

| On average, how many times you have given your child paracetamol in last 12 months? n (%) | |||

| Once a week | 634 (17.7%) | 373 (23.3%) | 1007 (19.4%) |

| Once a month | 1765 (49.2%) | 740 (46.2%) | 2505 (48.3%) |

| Once a year | 860 (24.0%) | 258 (16.1%) | 1118 (21.5%) |

| Missing | 326 (9.1%) | 232 (14.5%) | 558 (11.0%) |

| How many hours a day does your child watch TV? n (%) | |||

| <3 hours | 2167 (60.5%) | 960 (60.0%) | 3127 (60.3%) |

| >3 hours | 1230 (34.3%) | 557 (34.7%) | 1787 (34.4%) |

| Missing | 188 (5.2%) | 86 (5.4%) | 274 (5.3%) |

| How many times a week did your child take exercise? n (%) | |||

| Never | 2262 (63.1%) | 1253 (78.2%) | 3515 (67.8%) |

| Once or twice a week | 774 (21.6%) | 191 (12.0%) | 965 (18.6%) |

| Three times or more | 298 (8.3%) | 39 (2.4%) | 337 (6.5%) |

| Missing | 251 (7.0%) | 120 (7.5%) | 371 (7.2%) |

| Does your home have air conditioning? n (%) | |||

| Electric fan only | 28 (0.8%) | 24 (1.5%) | 52 (1.0%) |

| Water system only | 219 (6.1%) | 516 (32.2%) | 735 (14.2%) |

| Freon system only | 3106 (86.6%) | 976 (61.0%) | 4082 (78.7%) |

| Both Freon & water systems | 55 (1.5%) | 19 (1.2%) | 74 (1.4%) |

| Missing | 177 (5.0%) | 68 (4.2%) | 245 (4.7%) |

| How many times on average does a truck pass the street adjacent to your home? n (%) | |||

| Rarely | 2350 (65.6%) | 1105 (69.0%) | 3455 (66.6%) |

| Frequently | 1087 (30.3%) | 433 (27.0%) | 1520 (29.3%) |

| Missing | 148 (4.1%) | 65 (4.1%) | 213 (4.1%) |

| What is the fuel normally used in cooking in your household? n (%) | |||

| Electricity only | 154 (4.3%) | 49 (3.1%) | 203 (4.0%) |

| Gas only | 3270 (91.2%) | 1484 (92.6%) | 4754 (91.6%) |

| Wood fire or coal | 3 (0.1%) | 7 (0.4%) | 10 (0.2%) |

| Both Electricity & gas | 48 (1.3%) | 20 (1.2%) | 68 (1.3%) |

| Missing | 110 (3.1%) | 43 (2.7%) | 153 (2.9%) |

| Diet – how many times a week does your child eat the following? | |||

| Meat n (%) | |||

| Never | 244 (7.0%) | 135 (8.4%) | 379 (7.3%) |

| Once or twice a week | 1169 (32.6%) | 553 (34.5%) | 1722 (33.4%) |

| Three or more a week | 2052 (57.2%) | 859 (53.6%) | 2911 (56.1%) |

| Missing | 120 (3.3%) | 56 (3.5%) | 176 (3.4%) |

| Fish n (%) | |||

| Never | 1631 (45.5%) | 744 (46.4%) | 2375 (45.8%) |

| Once or twice a week | 1606 (44.8%) | 689 (43.0%) | 2295 (44.2%) |

| Three or more a week | 171 (4.8%) | 76 (4.7%) | 247 (4.8%) |

| Missing | 177 (4.9%) | 94 (6.0%) | 271 (5.2%) |

| Fruit n (%) | |||

| Never | 534 (14.9%) | 173 (10.8%) | 707 (13.6%) |

| Once or twice a week | 1500 (41.8%) | 686 (42.8%) | 2186 (42.2%) |

| Three or more a week | 1431 (40.0%) | 677 (42.2%) | 2108 (40.6%) |

| Missing | 120 (3.3%) | 67 (4.2%) | 187 (3.6%) |

| Vegetables n (%) | |||

| Never | 444 (12.4%) | 152 (9.5%) | 596 (11.5%) |

| Once or twice a week | 1313 (36.6%) | 580 (36.2%) | 1893 (36.5%) |

| Three or more a week | 1623 (45.3%) | 779 (48.6%) | 2402 (46.3%) |

| Missing | 205 (5.7%) | 92 (5.7%) | 297 (5.7%) |

| Legumes n (%) | |||

| Never | 1180 (33.0%) | 483 (30.1%) | 1663 (32.1%) |

| Once or twice a week | 1555 (43.4%) | 680 (42.4%) | 2235 (43.1%) |

| Three or more a week | 673 (18.8%) | 347 (21.7%) | 1020 (19.7%) |

| Missing | 177 (4.9%) | 93 (5.8%) | 270 (5.2%) |

| Cereal n (%) | |||

| Never | 97 (2.7%) | 41 (2.6%) | 138 (2.7%) |

| Once or twice a week | 394 (11.0%) | 181 (11.3%) | 575 (11.1%) |

| Three or more a week | 2935 (82.0%) | 1291 (80.5%) | 4226 (81.5%) |

| Missing | 159 (4.4%) | 90 (5.6%) | 249 (4.8%) |

| Pasta n (%) | |||

| Never | 764 (21.3%) | 338 (21.1%) | 1102 (21.3%) |

| Once or twice a week | 1915 (53.4%) | 862 (53.8%) | 2777 (53.5%) |

| Three or more a week | 755 (21.1%) | 335 (21.0%) | 1090 (21.0%) |

| Missing | 151 (4.2%) | 68 (4.2%) | 219 (4.2%) |

| Rice n (%) | |||

| Never | 136 (3.8%) | 50 (3.1%) | 186 (3.6%) |

| Once or twice a week | 744 (20.8%) | 336 (21.0%) | 1080 (20.8%) |

| Three or more a week | 2549 (71.1%) | 1133 (70.7%) | 3682 (71.0%) |

| Missing | 156 (4.4%) | 84 (5.2%) | 240 (4.6%) |

| Butter n (%) | |||

| Never | 2072 (57.8%) | 943 (58.8%) | 3015 (58.1%) |

| Once or twice a week | 942 (26.3%) | 373 (23.3%) | 1315 (25.3%) |

| Three or more a week | 343 (9.6%) | 168 (10.5%) | 511 (10.0%) |

| Missing | 228 (6.4%) | 119 (7.4%) | 347 (6.7%) |

| Margarine n (%) | |||

| Never | 2225 (62.1%) | 1008 (62.9%) | 3233 (62.3%) |

| Once or twice a week | 657 (18.3%) | 278 (17.3%) | 935 (18.0%) |

| Three or more a week | 378 (10.5%) | 158 (9.9%) | 536 (10.3%) |

| Missing | 325 (9.1%) | 159 (10.0%) | 484 (9.4%) |

| Nuts n (%) | |||

| Never | 1905 (53.1%) | 806 (50.3%) | 2711 (52.3%) |

| Once or twice a week | 1168 (32.6%) | 550 (34.3%) | 1718 (33.1%) |

| Three or more a week | 295 (8.2%) | 148 (9.2%) | 443 (8.5%) |

| Missing | 217 (6.1%) | 99 (6.2%) | 316 (6.1%) |

| Potatoes n (%) | |||

| Never | 284 (8.0%) | 144 (9.0%) | 428 (8.3%) |

| Once or twice a week | 1662 (46.4%) | 690 (43.0%) | 2352 (45.3%) |

| Three or more a week | 1488 (41.5%) | 703 (43.9%) | 2191 (42.2%) |

| Missing | 151 (4.2%) | 66 (4.1%) | 217 (4.2%) |

| Milk n (%) | |||

| Never | 300 (8.4%) | 127 (8.0%) | 427 (8.3%) |

| Once or twice a week | 773 (21.6%) | 358 (22.3%) | 1131 (21.8%) |

| Three or more a week | 2383 (66.5%) | 1063 (66.3%) | 3446 (66.4%) |

| Missing | 129 (3.6%) | 55 (3.4%) | 184 (3.5%) |

| Eggs n (%) | |||

| Never | 391 (11.0%) | 186 (11.6%) | 577 (11.1%) |

| Once or twice a week | 1353 (37.7%) | 587 (36.6%) | 1940 (37.4%) |

| Three or more a week | 1697 (47.3%) | 751 (46.8%) | 2448 (47.2%) |

| Missing | 144 (4.0%) | 79 (5.0%) | 223 (4.3%) |

| Fast food n (%) | |||

| Never | 2088 (58.3%) | 1020 (63.6%) | 3108 (60.0%) |

| Once or twice a week | 1033 (28.8%) | 377 (23.5%) | 1410 (27.2%) |

| Three or more a week | 281 (7.8%) | 119 (7.4%) | 400 (7.7%) |

| Missing | 183 (5.1%) | 87 (5.5%) | 270 (5.2%) |

Overall Prevalence of Symptoms Suggestive of Allergic Problems

Overall, 2,163 children (41.7%, 95%CI 39.1, 44.4) had symptoms suggestive of at least one allergic problem.

Prevalence of Parental Reports of Symptoms Suggestive of, Current and Clinician-diagnosed Eczema, Rhinitis and Asthma

In the section below we summarise data on the overall prevalence of parental reports of symptoms suggestive of, diagnosed and current eczema, rhinitis and asthma. The 95%CI for these estimates are presented in Table 2 together with sex-related variations and corresponding 95%CIs.

Table 2. Prevalence of parental reports of symptoms of, diagnosed and current allergic disease in 6–8 year old children.

| Parental-reported outcomes | Females n, percent (95%CI) | Males n, percent (95%CI) | Total n, percent (95%CI) |

| Ever had symptoms of eczema | 148, 9.2% (7.5, 11.3) | 389, 10.9% (9.8, 12.0) | 537, 10.4% (9.4, 11.4) |

| Ever had symptoms of rhinitis | 300, 18.7% (16.9, 20.7) | 957, 26.7% (25.0, 28.5) | 1257, 24.2% (22.3, 26.2) |

| Ever had symptoms of asthma | 351, 21.9% (17.4, 27.1) | 874, 24.4% (22.0, 26.9) | 1225, 23.6% (21.3, 26.0) |

| Diagnosed eczema | 186, 11.6% (9.8, 13.7) | 540, 15.1% (12.9, 17.5) | 726, 14.0% (12.2, 15.9) |

| Diagnosed rhinitis | 52, 3.2% (2.4, 4.4) | 164, 4.6% (4.0, 5.2) | 216, 4.2% (3.6, 4.7) |

| Diagnosed asthma | 196, 12.2% (10.1, 14.7) | 607, 16.9% (15.5, 18.4) | 803, 15.5% (14.1, 17.0) |

| Eczema symptoms in last 12 months | 122, 7.6% (5.9, 9.8) | 332, 9.3% (8.2, 10.5) | 454, 8.8% (7.8, 9.8) |

| Rhinitis symptoms in last 12 months | 229, 14.3% (12.2, 16.7) | 716, 20.0% (18.3, 21.7) | 945, 18.2% (16.6, 20.0) |

| Asthma symptoms in last 12 months | 113, 7.0% (5.0, 9.9) | 416, 11.6% (10.5, 12.9) | 529, 10.2% (8.9, 11.7) |

Eczema

Overall, 10.4% of parents reported a history of a chronic (≥6 months) itchy rash in their children. The prevalence of parental reports of symptoms of itchy rash at any time in the last 12 months was 8.8%. There were parental reports of clinician-diagnosed eczema in 14.0% of children.

Rhinitis

Symptoms suggestive of ever-having had allergic rhinitis were common, affecting 24.2% of children overall, with an estimated 18.2% experiencing symptoms of sneezing in the last 12 months. The prevalence of children with parental reports of ever having a clinician diagnosis of allergic rhinitis was 4.2% overall.

Asthma

The overall prevalence of ever-having had wheeze or whistling in the chest was 23.6%, with reports of symptoms of asthma in the previous 12 months in 10.2% of children. The overall prevalence of children with parental reports of ever having been diagnosed with asthma was 15.5%.

Co-morbid Allergic Disease

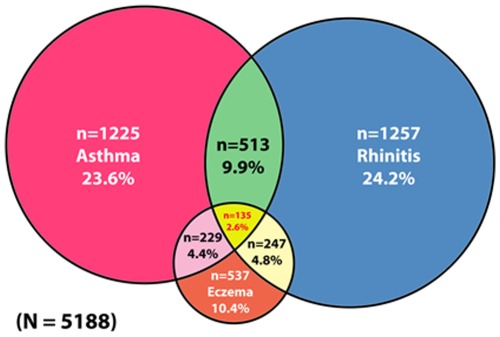

Whilst the majority (1447/2163; 66.9%) of children had symptoms suggestive of only one allergic condition, as demonstrated in Table 3 and Figure 1 a substantial minority of children had symptoms suggestive of co-morbid allergic disease.

Table 3. Prevalence of symptoms of co-morbid allergic disease in 6–8 year old children in Madinah, Saudi Arabia.

| Co-morbidities | Females n, percent (95%CI) | Males n, percent (95%CI) | Total n, percent (95%CI) |

| Rhinitis and asthma | 114, 7.1% (5.4, 9.3) | 399, 11.1% (10.1, 12.2) | 513, 9.9% (8.7, 11.1) |

| Asthma and eczema | 64, 4.0% (3.1, 5.2) | 165, 4.6% (3.9, 5.4) | 229, 4.4% (3.8, 5.1) |

| Rhinitis and eczema | 61, 3.8% (3.1, 4.7) | 186, 5.2% (4.6, 5.9) | 247, 4.8% (4.2, 5.4) |

| Eczema, rhinitis and asthma | 30, 1.9% (1.3, 2.6) | 105, 2.9% (2.5, 3.4) | 135, 2.6% (2.2, 3.0) |

Figure 1. Venn diagram of patterns of co-morbid allergic disease in 6–8 year olds in Madinah, Saudi Arabia.

International Comparisons

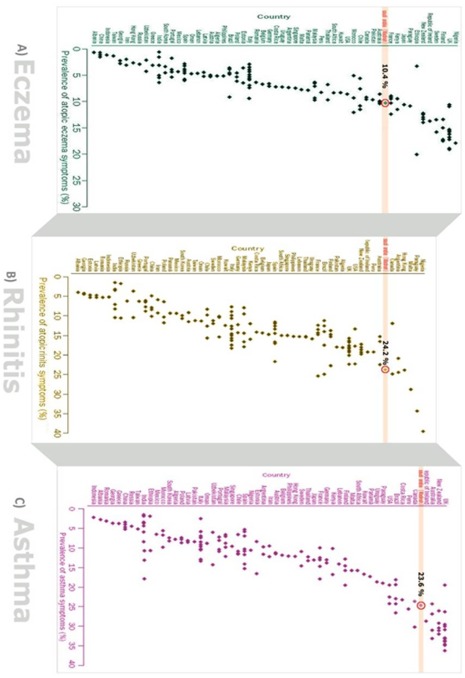

Figure 2 compares the prevalence estimates obtained from our study with data from other parts of the world, these revealing that Madinah is internationally a very high prevalence region.

Figure 2. Comparison of prevalence of parental reports of symptoms of: a) eczema; b) rhinitis symptoms; and c) asthma in 6–8 year old Saudi children compared with 6–7 year old children in ISAAC participating countries in 1998 survey (2) (Saudi highlighted).

Discussion

This is, we believe, the largest study on the prevalence of allergic disease in school-aged children ever undertaken in the Arab world. The findings indicate that the prevalence of these problems is very high – affecting over 40% of children – within the first eight years of life. This is concerning given the considerable disease burden associated with these conditions, both to individuals and to society more generally [11]–[14].

Strengths and Limitations of this Study

The main strengths of this study include the large sample size and the very high response rate, which is likely to be due to the combinaton of achieving good support from the participating schools and the fact that we were undertaking work in a population that has not previously been investigated, hence research fatigue was not an issue. Unlike the majority of previous studies, we did not confine ourselves to studying the prevalence of asthma [6]–[7]; [15]–[18]. Rather, we looked at other most common allergic problems, namely eczema and rhinitis; we also studied the co-morbidity between these conditions. The use of a validated instrument was an additional strength, particularly since this offered the opportunity to compare prevalence estimates for children from Madinah with children of a similar age from across the world (Figure 2) [19].

This major limitation with this work is that it was conducted in only one city in Saudi Arabia in children of one age group; these findings may therefore not be generalisable to other sections of Saudi society. It is important that similar studies are now conducted in other urban and rural locations in Saudi Arabia in children of other age groups. There is also the need to build on this work and monitor allergic disease trends in the Madinah region [20]. Finally, as we had no data that allowed us to compare the characteristics of responders and non-responders, care must be taken in seeking to extrapolate data from this work across the entire Madinah region.

Comparison with the Wider Literature

The limited previous literature has suggested that the prevelance of asthma in Middle Eastern countries is lower than in “developed” countries[6]–[7]; [15]–[18]. a finding that is challenged by our study. Our study also proints to the high prevealcne of eczema and rhinitis in these children (Figure 2). This work has also highlighted the issue of possible under-diagnosis of rhinitis, and possibly also asthma, which echoes the findings from previous studies [21]–[22].

Implications for Public Health Policy, Research and Practice

This work has identified the high prevalence of allergic disorders in Madinah and given the fact that these conditions are likely to continue to pose a significant burden to both individuals and society over the lifecourse, this suggests that allergic problems are likely to be an important public health consideration in Saudi Arabia for many years to come [13]–[14]; [23]. Given the very high prevalences of disease found in Madinah, it is important that this work is now extended to other Saudi regions; it is also important that attempts are made to understand key potentially modifiable environmental risk factors, which we will be reporting on in due course. It is furthermore also important that this population-based work is repeated in due course to allow disease trends to be determined [24]–[26]. Comparing the prevalence of symtomatic and clinician-diagnosed disease suggests that there may be substantial under-diagnosis of allergic rhinitis and to a lesser extent asthma. There is therefore a need for work to be now undertaken to verify this and, if confirmed, take steps to impove diagnostic capacity and accuracy, particualrly in community-based clinical seetings. Finally, there is the need for related work investigating the quality of care provided to children with allergic problems as this has been found to be wanting in other parts of the world [21]–[22].

Conclusions

This large study of allergic disease prevalence in primary school-aged children in Madinah, Saudi Arabia has found that over 40% of children manifest symptoms indicative of allergic disease prevalence within the first eight years of life, these figures ranking amongst the highest in the world. More work is now needed on assessing the prevalence of allergic problems in other parts of Saudi Arabia, other age groups, and in monitoring disease trends. Given these very high figures, the Saudi Government needs to give careful consideration to developing health and educational policies that ensure the effective treatment of these children whilst minimising the impact of these conditions on educational performance; there is furthermore a need to understand better what is driving this epidemic in Saudi children and prioritise the search for effective primary prevention strategies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the General Directorate of Education in Madinah region, the General Directorate of School Health in the Ministry of Education in Riyadh (both boys and girls sections), the research team (males and females), and all staff in participating schools. We wish to record our appreciation to the parents and children who participated in this study. Our thanks are also due to Elsevier for permssion to adapt and reproduce Figure 2. Finally, we are grateful to the reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: Funding came from a Saudi Arabia Ministry of Higher Education Scholarship. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Punekar YS, Sheikh A. Establishing the incidence and prevalence of clinician-diagnosed allergic conditions in children and adolescents using routinely collected data from general practices. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:1209–1216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ISAAC Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Steering Committee. Lancet. 1998;351:1225–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asher MI, Keil U, Anderson HR, Beasley R, Crane J, Martinez F, et al. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:483–491. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08030483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Community Respiratory Health Survey. Variations in the prevalence of respiratory symptoms, self-reported asthma attacks, and use of asthma medication in the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS). Eur Respir J. 1996;9:687–695. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09040687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ait-Khaled N, Enarson DA, Ottmani S, El Sony A, Eltigani M, Sepulveda R. Chronic airflow limitation in developing countries: burden and priorities. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2007;2:141–150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hijazi N, Abalkhail B, Seaton A. Asthma and respiratory symptoms in urban and rural Saudi Arabia. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:41–44. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12010041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Dawood K. Epidemiology of bronchial asthma among school boys in Al-Khobar city, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2001;22:616–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ISAAC Tools – Arabic Version. 14 Available: http://isaac.auckland.ac.nz/resources/tools.php?menu=tools1 Accessed 2011 Apr. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Central Department of Statistics. 14 Available: http://www.cdsi.gov.sa/asp/indexeng.asp Accessed 2011 Apr. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanley JA, Negassa A, Edwardes MD, Forrester JE. Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: an orientation. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:364–375. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Mutius E. The burden of childhood asthma. Arch Dis Child 82 (Suppl. 2000;2):II2–5. doi: 10.1136/adc.82.suppl_2.ii2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker S, Khan-Wasti S, Fletcher M, Cullinan P, Harris J, Sheikh A. Seasonal allergic rhinitis is associated with a detrimental impact on exam performance in UK teenagers: case-control study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta R, Sheikh A, Strachan DP, Anderson HR. Burden of allergic disease in the UK: secondary analyses of national databases. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:520–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.1935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anandan C, Gupta R, Simpson CR, Fischbacher C, Sheikh A. Epidemiology and disease burden from allergic disease in Scotland: analyses of national databases. J R Soc Med. 2009;102:431–442. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2009.090027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janahi IA, Bener A, Bush A. Prevalence of asthma among Qatari schoolchildren: International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, Qatar. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2006;41:80–86. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasan MM, Gofin R, Bar-Yishay E. Urbanization and the risk of asthma among schoolchildren in the Palestinian Authority. J Asthma. 2000;37:353–360. doi: 10.3109/02770900009055459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Frayh A, Bener A, Al-Jawadi T. Prevalence of asthma among Saudi schoolchildren. Saudi Med J. 1993;13:521–524. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Frayh AR, Shakoor Z, Gad El Rab MO, Hasnain SM. Increased prevalence of asthma in Saudi Arabia. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001;86(3):92–96. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)63301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asher MI, Montefort S, Bjorksten B, Lai CK, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006;368:733–743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anandan C, Nurmatov U, van Schayck OC, Sheikh A. Is the prevalence of asthma declining? Systematic review of epidemiological studies. Allergy. 2009;65:152–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryan D, Grant-Casey J, Scadding G, Pereira S, Pinnock H, Sheikh A. Management of allergic rhinitis in UK primary care: baseline audit. Prim Care Respir J. 2005;14:204–209. doi: 10.1016/j.pcrj.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryan D, Levy M, Morris A, Sheikh A, Walker S. Management of allergic problems in primary care: time for a rethink? Prim Care Respir J. 2005;14:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.pcrj.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Punekar YS, Sheikh A. Establishing the sequential progression of multiple allergic diagnoses in a UK birth cohort using the General Practice Research Database. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:1889–1895. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simpson CR, Newton J, Hippisley-Cox J, Sheikh A. Trends in the epidemiology and prescribing of medication for eczema in England. J R Soc Med. 2009;102:108–117. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2009.080211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghouri N, Hippisley-Cox J, Newton J, Sheikh A. Trends in the epidemiology and prescribing of medication for allergic rhinitis in England. J R Soc Med. 2008;101:466–472. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2008.080096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simpson CR, Sheikh A. Trends in the epidemiology of asthma in England: a national study of 333,294 patients. J R Soc Med. 2010;103:98–106. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2009.090348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]