Abstract

Background

An increase in elbow pathology in adolescents has paralleled an increase in sports participation. Evaluation and classification of these injuries is challenging because of limited information regarding normal anatomy. The purpose of this study was to evaluate normal radiographic anatomy in adolescents to establish parameters for diagnosing abnormal development. Established and new measurements were evaluated for reliability and variance based on age and sex.

Methods

Three orthopaedic surgeons independently and in a standardized fashion evaluated the normal anteroposterior and lateral elbow radiographs of 178 adolescent and young adult subjects. Fourteen measurements were performed including radial neck- shaft angle, articular surface angle, articular surface morphologic assessment (subjective and objective evaluation of the patterns of ridges and sulci), among others. We performed a statistical analysis by age and sex for each measure and assessed for inter and intra-observer reliability.

Results

The distal humerus articular surface was relatively flat in adolescence and became more contoured with age as objectively demonstrated by increasing depth of the trochlear and trochleocapitellar sulci, and decreasing trochlear notch angle. Overall measurements were similar between males and females, with an increased carrying angle in females. There were several statistically significant differences based on age and sex but these were small and unlikely to be clinically significant. Inter and intra-observer reliability were variable; some commonly utilized tools had poor reliability.

Conclusions

Most commonly utilized radiographic measures were consistent between sexes, across the adolescent age group, and between adolescents and young adults. Several commonly used assessment tools show poor reliability.

Level of evidence

Basic Science Study, Anatomic Study, Imaging

Keywords: Elbow, Radiograph, X-ray, Anatomy, Adolescent

Introduction

Very little information exists describing the normal radiographic anatomy of the elbow in the pediatric and adolescent population, making diagnosis and classification of injury difficult for both clinical and research purposes. Previous literature focuses primarily on fracture outcomes,4, 9, 26, 28 ossification7 patterns, and gender differences.1, 3, 17, 23 There is no information however, describing normal morphology of the developing distal humerus and proximal olecranon and radius. This anatomy is increasingly important in evaluating abnormalities such as osteonecrosis of the capitellum (Panner’s disease), osteochondral defects, and medial apophysitis (Little League elbow), for example. In order to establish treatment algorithms and evaluate outcomes, common and reliable methods of measurement and assessment are necessary.

Many early manuscripts evaluated outcome after pediatric elbow fractures and identified radiographic assessment tools to aid in the treatment of these fractures, such as Baumann’s angle.4, 9, 26, 28 Cheng et al. examined the development of the ossification centers and reported that, on average, boys’ elbows mature 2 years later than girls.7 Keenan and Clegg evaluated the Baumann’s angle at multiple age intervals and reported no statistically significant differences between the sexes.17 Although previous investigations noted gender differences in the carrying angle of the elbow,1, 3, 23 in an evaluation of 422 subjects, Beals reported no significant difference in carrying angle existed based on gender.5 A recent investigation in adults presented several new measurement techniques in an effort to identify predisposing factors for elbow arthrosis;25 it stands out as one of the only recent investigations in the literature with objective data. These studies, some conflicting, still offer little information on evaluation of normal and pathologic development of the elbow. Furthermore, they don’t address normal anatomic variances.

Many radiographic measurement techniques are utilized regularly for clinical care and yet no comprehensive assessment of the reliability or usefulness of these techniques has been performed. The lack of objective data on the radiographic anatomy of the elbow is troublesome and is demonstrated most notably in textbook chapters which provide useful overviews but very limited actual data.6, 15, 22, 34, 35 The purpose of this study was to address this lack of objective data via an evaluation of a large number of normal adolescent and young adult elbows in order to

Establish a set of normal radiographic criteria that can be used for comparative investigations of elbow pathology,

Define normal elbow development based on radiographic criteria, and

Assess intra and inter-observer reliability for commonly utilized radiographic measurements.

Materials and Methods

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for this investigation and a total of 180 subjects were recruited. One hundred and forty skeletally immature or adolescent subjects, including 70 males and 70 females between the ages of 12 and 18, were assigned a bone age based on established criteria13 providing 10 male and 10 female elbows at each bone age. An additional 40 skeletally mature subjects, 20 male and 20 female, between the ages of 18 and 25 years, were recruited as the young adult group.

Subjects were recruited at our pediatric orthopaedic hospital from the clinic populations of the principal investigator and collaborators. While some of these subjects presented to the hospital for lower extremity trauma, most were unaffected siblings or friends. A brief clinical history was obtained in order to rule out previous injury or upper extremity abnormality, and a focused physical examination was performed. A normal clinical examination has been associated with normal x-rays, especially in younger populations.19

Subjects were excluded from participation if there was a possibility of pregnancy or if there was evidence of:

a syndrome affecting the musculoskeletal system

a growth abnormality

a congenital abnormality of the upper extremity of any kind

a history of fracture of the humerus, elbow, or forearm

a history of elbow pain or pain during clinical assessment

any abnormality of elbow alignment or elbow motion

Once the entrance criteria were satisfied, each subject had three radiographs of the non dominant elbow performed in a standardized fashion: an anterior-posterior (AP) radiograph in full extension with the forearm in supination, a lateral radiograph with the elbow at 90 degrees and the forearm in neutral rotation, and a posterior-anterior (PA) radiograph of the hand for subjects younger than 18 years (to determine bone age). Unsatisfactory films were repeated in order to maintain consistency. Radiographic data were de-identified and marked for sex and chronological age only.

Hand radiographs were assessed using the Greulich and Pyle method, a technique which utilizes an atlas of hand radiographs as a comparison to allow assignment of skeletal age.13

Radiographic Evaluation

Independently, 3 upper extremity surgeons evaluated each radiograph for a variety of measures. Measurement parameters, both established and original, were identified to characterize the developing elbow. The outline of the humerus, radius and ulna were traced on translucent paper to allow angular measurements for both the AP and lateral views. A mechanical pencil (#2 pencils with 0.5mm leads, BIC; Shelton, CT, USA) was used for tracing the bone outlines in order to facilitate detailed measurements. A goniometer (Sammons Preston; Bolingbrook, IL, USA) was utilized for these angular measurements, recorded to the nearest whole degree, and a 7x magnifying loupe (Electro- Optix; Pompano Beach, FL, USA) was utilized for distance measurements. Once all measurements had been completed, and at least 3 months after the initial measurements, 10% of the radiographs were re-measured by each evaluator to allow an assessment of intra- observer reliability.

Measurements on AP radiograph

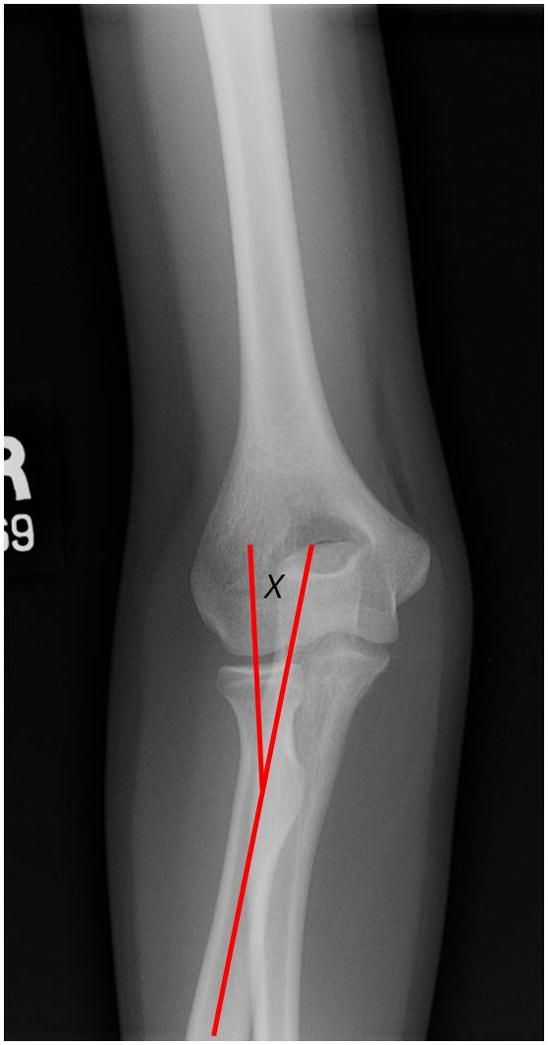

Radial Neck- Shaft Angle. The angle between a longitudinal line perpendicular to the articular surface of the radial neck and a longitudinal line along the radial shaft was measured.10 (Figure 1) Previous reported normal value: 15 degrees.35

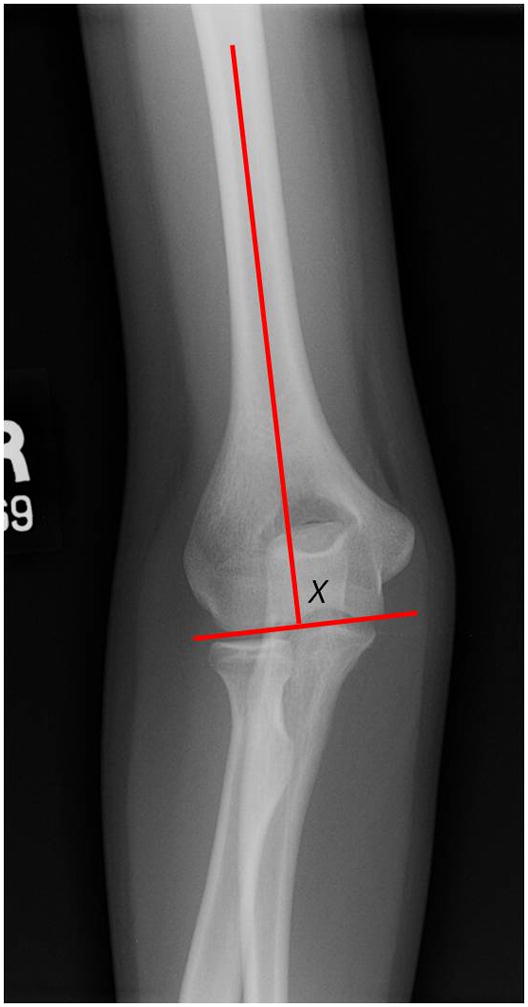

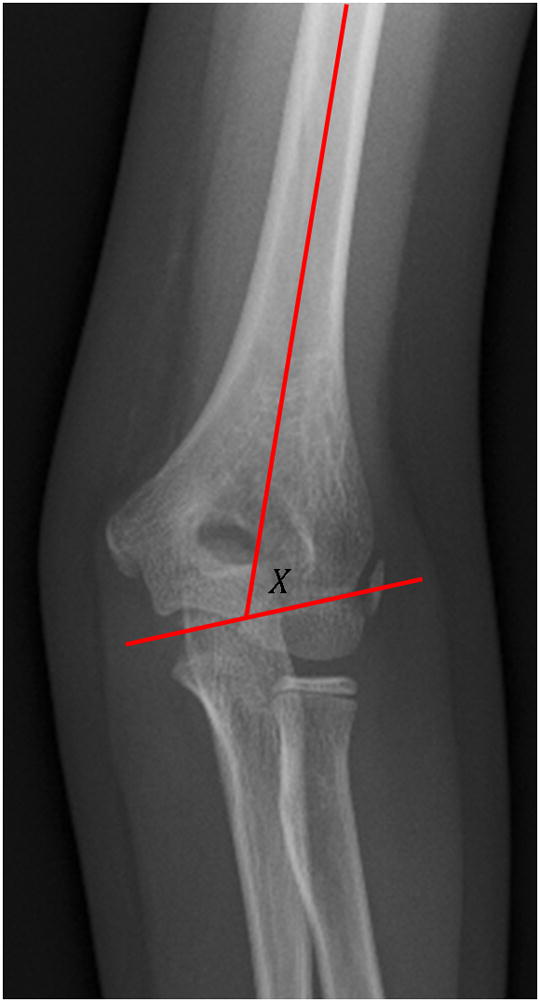

Articular Surface Angle. The angle between the longitudinal axis of the humerus shaft and a transverse line drawn along the most distal aspect of the bony trochlea and the capitellum was measured.16, 34 An increasing angle (i.e., closer to 90 degrees) represents decreasing valgus through the distal humerus. (Figure 2) Previous reported normal values: 82–84 degrees;35 85 degrees for males, 84 degrees for females.16

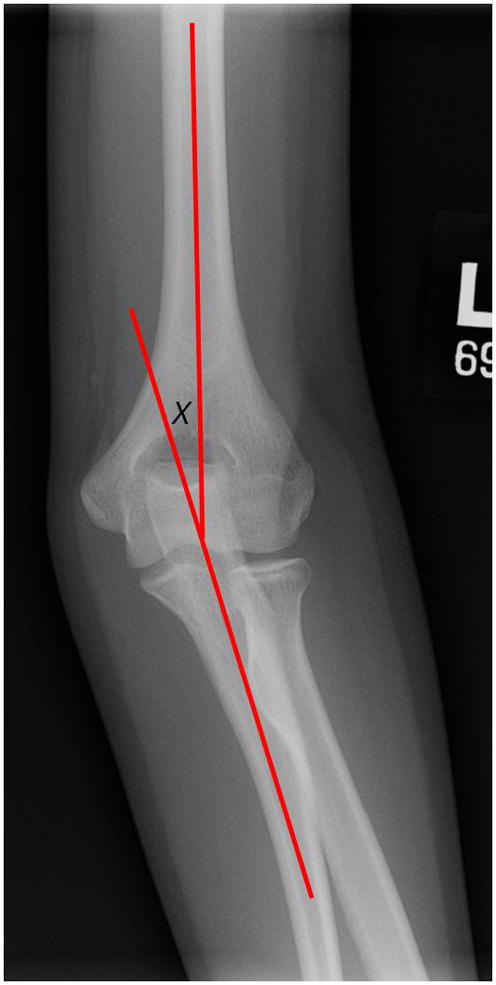

Carrying Angle. The angle between the longitudinal axis of the humerus shaft and a longitudinal drawn along the shaft of the ulna. The axis of the humerus and ulna were determined by at least 2 central points of each bone.1, 5, 16, 34 A positive angle represents valgus alignment. (Figure 3) Previous reported normal value: 10–15 degrees males, 15–20 degrees females;38 6.84 degrees males, 12.65 degrees females;23 11 degrees males, 15 degrees females;3 11 degrees males, 13 degrees females;16 10 degrees;21 15 degrees infants, 17.8 degrees adults.5

-

Articular Surface Assessment. The morphology of the distal surface of the humerus was assessed using subjective and objective parameters.

First, the surface contour was subjectively evaluated adjacent to the lateral trochlear ridge, including an evaluation of the size of the ridge and the depth of the sulci (trochlear sulcus and trochleocapitellar sulcus) adjacent to it. Three distinct patterns emerged: a flat contour (Type I), a small ridge with shallow adjacent sulci (Type II), and a prominent ridge with deep sulci. (Type III). (Figure 4a,b,c)

-

Depth. A magnifying loupe was utilized to assess the distance from the perpendicular drawn along the distal articular surface of the distal humerus to the depth of the trochlear sulcus- the most medial sulcus- and the trochleocapitellar sulcus- the most lateral sulcus. These two sulci are separated by the lateral ridge of the trochlea. The distance between the perpendicular and the most distal aspect of the ridge was measured. The following 3 measurements were recorded in millimeters. (Figure 5)

Trochlear sulcus

Lateral trochlear ridge

Trochleocapitellar sulcus (sulcus between the lateral trochlear ridge and the capitellum)

The Baumann angle was assessed in subjects with an open physis. We measured the angle between a longitudinal drawn along the humerus shaft and a line along the open capitellar physis.4, 9, 28 (Figure 6) Previous reported normal value: 64–82 degrees males, 69–81 degrees females;17 64–81 degrees, mean 72 degrees;36 75–80 degrees.4

Trochlear Notch Angle. The angle between the medial and lateral facets of the trochlea was measured. (Figure 7)

Figure 1.

Radial neck shaft angle

Figure 2.

Articular surface angle

Figure 3.

Carrying angle

Figure 4.

Figure 4a. Example of Types I distal humerus contour

Figure 4b. Example of Types II distal humerus contour

Figure 4c. Example of Types III distal humerus contour

Figure 5.

Measurement technique for lateral ridge height and depths of trochlear sulcus and trochleocapitellar sulcus. The three points are marked and measured with a magnifying loupe to allow quantification. The articular surface angle measurement is also depicted in this overlay.

Figure 6.

Baumann angle

Figure 7.

Trochlear notch angle

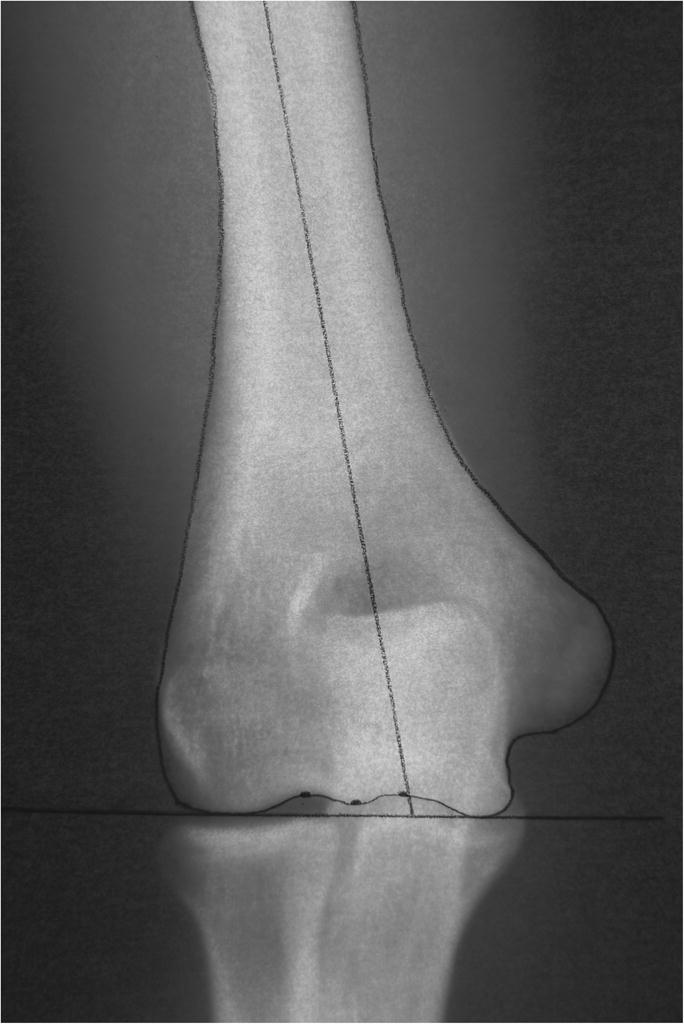

Measurements on Lateral Radiograph

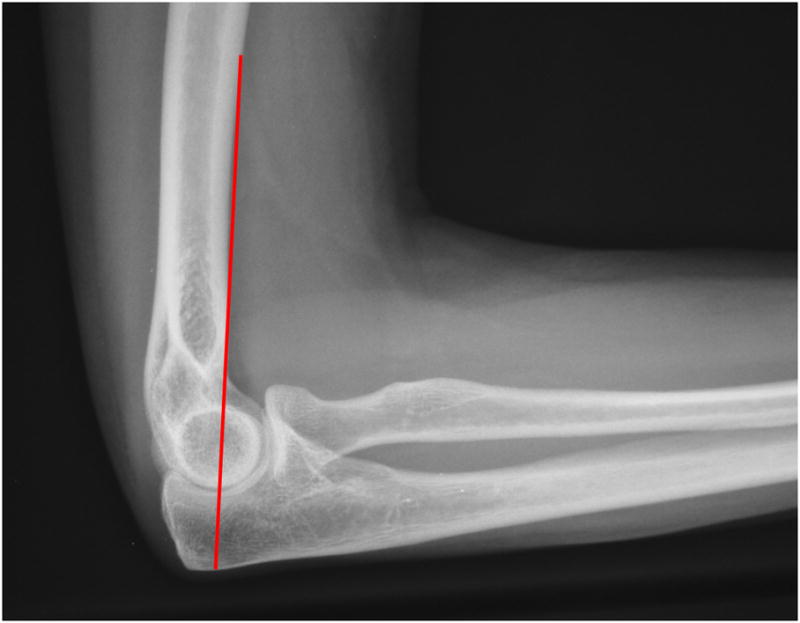

Anterior Humeral- Capitellar Line. A line was drawn along the anterior surface of the distal humerus. The line was continued distally to record its relationship with the capitellum as central 1/3rd, anterior 1/3rd, or posterior 1/3rd.26 The mode and the mean were recorded to allow comparison between age groups and the sexes. (Figure 8) Previous reported normal value: Central 1/3rd.11, 12, 15, 26, 35 Posterior 1/3rd.14

Radiocapitellar Alignment. To assess the alignment on the lateral radiograph between the radial head/ neck and the capitellum, a line was drawn longitudinally along the central radial neck to assess its intersection point with the capitellum.27, 31, 32 This intersection line was recorded as central 1/3rd, anterior 1/3rd, or posterior 1/3rd. The mode and the mean were recorded to allow comparison between age groups and the sexes. (Figure 9) Previous reported normal value: Central 1/3rd.11, 34

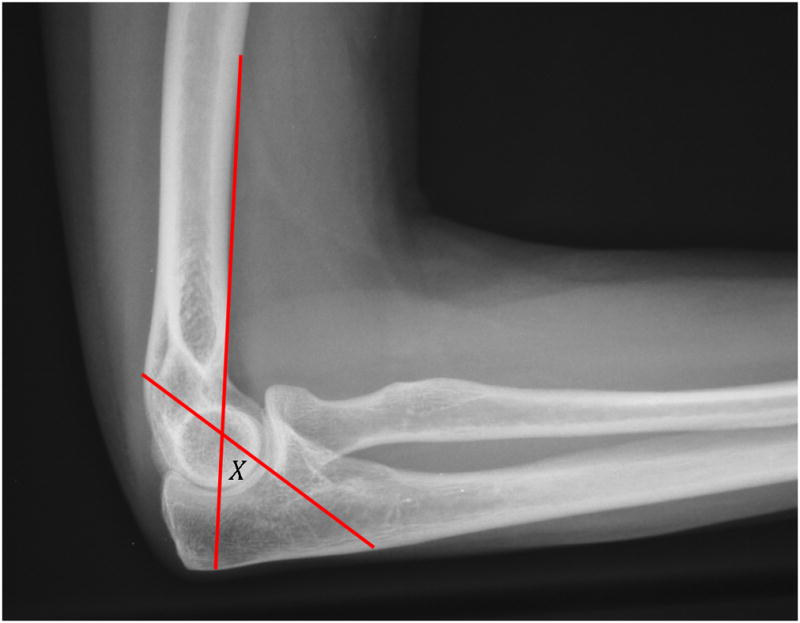

Anterior Angulation of Articular Surface of Distal Humerus. The angle between a line along the humeral shaft and a line bisecting the capitellum. (Figure 10) Previous reported normal value: 30 degrees;34 40.8, 15, 26

Olecranon- coronoid angle. The angle between a longitudinal along the long axis of the ulna and a line drawn along the olecranon tip and the coronoid tip. (Figure 11) Previous reported normal value: 30degrees;38 22.3 degrees males, 14.7 degrees females;24

Greater Sigmoid Notch Circle. The bony greater sigmoid notch represents a portion of a complete circle; theoretically, a more complete circle conveys additional stability to the elbow. To assess the depth of the greater sigmoid notch, we a circular template was utilized (Circles Inking Template Pickett 1200i; Chartpak; Leeds, MA, USA) to represent the notch and drew onto tracing paper the largest standard circle that would best fill the greater sigmoid notch. A line was drawn connecting the center of the circle to both the tip of the olecranon to the tip of the coronoid; the degrees of the circle below the line represented the depth of the notch. A larger degree measurement represented a deeper bony notch. This is a new measurement technique. (Figure 12)

Figure 8.

Anterior humeral- capitellar line

Figure 9.

Radiocapitellar alignment

Figure 10.

Anterior angulation of articular surface of distal humerus

Figure 11.

Olecranon- coronoid angle

Figure 12.

Measurement technique for greater sigmoid notch angle

Statistical Analysis

We utilized continuous measurements, averaged across the 3 raters, to examine differences in radiographic measurements by sex and separately by bone age group (adolescent, bone age 12–18 years and young adult, bone age 19–25 years). For categorical measurements, we utilized the category assigned by at least two of the three raters. Normally distributed continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations, while non-normally distributed continuous variables were summarized using medians and interquartile ranges. To compare continuous measurements by bone age group (adolescent or young adult) and separately by sex, Student’s t-test was used for normally distributed measurements and the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test was used for non-normally distributed measurements. Within the adolescent group, Spearman’s rank correlation was used to test the strength of the association between continuous bone age and the radiographic measurements. The type of bump at the articular surface (type I, II, and III) was compared by sex and by bone age group using Fisher’s exact test. One-way ANOVA was used to compare our subjective qualitative measurements of type of bump at the articular surface with objective quantitative measurements, with the Tukey HSD adjustment for multiple pair wise comparisons. All tests were two-tailed with P<.05 considered significant.

Original data from all three raters was used to assess reliability of measurements. Inter- and intra-observer reliability were calculated using intraclass correlation coefficients for quantitative measurements (ICC 2,1 for inter-rater; ICC 3,1 for intra-rater). Inter-rater reliability for categorical variables was calculated using Fleiss’ kappa for multiple raters (SAS macro %MAGREE). Intra-rater reliability for categorical variables was calculated using Cohen’s kappa. The suggested guidelines of Landis and Koch were used to interpret the magnitude of agreement: 0 is poor, 0–0.2 is slight, 0.21–0.40 is fair, 0.41–0.60 is moderate, 0.61–0.80 is substantial, and 0.81–1.0 is almost perfect agreement.18 SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) were used for analyses.

Results

One hundred eighty subjects were enrolled, but 2 subjects were excluded due to an altered radiographic appearance suggestive of a prior fracture. There were 85 males (48%) and 93 females (52%) included. The participants were grouped based on bone age, resulting in 125 adolescents (bone age 12–18 years) (70%) and 53 young adults (bone age 19–25 years) (30%). The proportion of subjects in each bone age group did not differ significantly by sex.

Measurements on AP Radiograph

AP radiographic measurements are presented in Table 1 by bone age group, and separately by sex. The adolescent bone age group had a larger articular surface angle, indicative of increased valgus alignment, than the young adult bone age group. The young adult bone age group had a deeper trochlear sulcus and trochleocapitellar sulcus, as well as a shallower lateral ridge, compared to the adolescent group.

Table 1.

AP Radiographic measurements by age group and sex

| Measurements (degrees) | Age groupa | Sex | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescents N=125 |

Young adults N=53 |

P | Males N=85 |

Females N=93 |

P | ||

| Radial neck shaft angle (0) | Mean (sd) | 12 (2) | 12 (2) | .688 | 12 (2) | 12 (2) | .077 |

| Articular surface angle (0) | Mean (sd) | 85 (4) | 84 (3) | .024 | 85 (3) | 85 (4) | .769 |

| Carrying angle (0) | Mean (sd) | 16 (5) | 16 (4) | .659 | 15 (5) | 17 (5) | .007 |

| Trochlear notch angle (0) | Mean (sd) | 126 (11) | 125 (8) | .198 | 126 (11) | 126 (10) | .861 |

| Trochlear sulcus (mm) | Mean (sd) | 4.6 (1.1) | 5.2 (0.9) | <.001 | 4.9 (1.1) | 4.7 (1.0) | .156 |

| Lateral ridge (mm) | Mean (sd) | 1.9 (0.8) | 2.2 (0.8) | .014 | 2.1 (0.8) | 1.9 (0.8) | .102 |

| Trochleocapiteller sulcus (mm)b | Median (IQR) | 2.6 (2.2–3.1) | 2.9 (2.7–3.3) | <.001 | 2.9 (2.5–3.5) | 2.6 (2.2–2.9) | <.001 |

Age groups based on bone age. Adolescents: bone age 12–18 years; Young adults: bone age 19–25 years

Not normally distributed. Thus medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) are reported, and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests were used instead of Students t-tests.

A larger percentage of young adults, compared to adolescents, demonstrated a Type III distal humeral morphology, trending toward significance (adolescents 23% type I, 63% type II, 14% type III; young adults 15% type I, 57% type II, 28% type III; p=0.059). Distal humerus morphology did not differ by gender.

Males had a deeper trochleocapitellar sulcus and females had a larger carrying angle. Baumann’s angle was measured only in young adolescents with open physis (n=28: 22 males and 6 females); this measurement did not differ between sexes (males mean 71, sd 4; females mean 70, sd 5).

When assessing continuous bone age with each of the AP radiograph measurements within the adolescent bone age group, increasing bone age was associated with an increase in lateral ridge angle (ρ = .299, p<.001), trochleocapitellar sulcus depth (ρ = .502, p<.001), and trochlear notch angle (ρ = .231, p=.009). Increasing bone age was associated with a decrease in articular surface angle (decreasing valgus) (ρ = −.281, p=.002).

We analyzed objective measurements in reference to our subjective assessment of the 3 contour types of the distal humerus (Table 2). There was a statistically significant difference between the 3 “bump types” (one- way ANOVA testing) based on an assessment of the lateral ridge, the trochleocapitellar sulcus, and the trochlear notch angle; the trochlear sulcus measurement was not significantly different among the bump types. No single measurement could be used to objectify our subjective classification of the articular contour but the lateral ridge measurement was most useful in separating Type III from Types I and II as the distance was significantly smaller in Type III. Type III had significantly larger trochleocapitellar sulcus than Type I. Trochlear notch angle was also lower (implying a steeper angle) in Type III compared to Type I.

Table 2.

Distal humerus morphology: Subjective and objective data

| Objective measurements | Subjective classification | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 (N=37) Mean (SD) |

Type 2 (N=109) Mean (SD) |

Type 3 (N=32) Mean (SD) |

P | |

| Trochlear sulcus (mm) | 4.73 (1.29) | 4.75 (1.00) | 4.85 (1.12) | .874 |

| Lateral ridge (mm)* | 2.09 (0.99) | 2.13 (0.68) | 1.50 (0.84) | .002 |

| Trochleocapitellar sulcus (mm)* | 2.15 (0.88) | 2.83 (0.70) | 2.92 (0.84) | <.001 |

| Trochlear notch angle* | 128.2 (12.9) | 126.3 (9.1) | 121.6 (9.0) | .019 |

Measurements on Lateral Radiograph

Lateral radiographic measurements are presented in Table 3 by bone age group and sex. Males had a larger anterior angulation of articular surface of distal humerus and olecranon-coronoid angle than females. The young adult bone age group had a larger greater sigmoid notch circle than the adolescent group.

Table 3.

Lateral radiographic measurements by age group and sex

| Measurements (degrees) | Age groupa | Sex | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescents N=125 |

Young adults N=53 |

P | Males N=85 |

Females N=93 |

P | |

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |||

| Anterior angulation of articular surface of distal humerusb | 118.7 (115.3 – 123.0) | 121.7 (117.7 – 125.0) | .088 | 120.3 (117.3 – 124.3) | 118.3 (115.0 – 123.0) | .013 |

| Olecranon-coronoid angleb | 23.7 (18.3 – 27.3) | 23.0 (21.0 – 25.7) | .913 | 24.3 (21.3 – 27.7) | 22.3 (18.3 – 25.3) | .004 |

| Greater sigmoid notch circleb | 180.7 (174.3 – 186.7) | 183.7 (177.0 – 191.7) | .022 | 181.7 (173.3 – 186.7) | 183.0 (176.7 – 189.0) | .187 |

Age groups based on bone age. Adolescents: bone age 12–18 years; Young adults: bone age 19–25 years

Not normally distributed. Thus medians and interquartile ranges are reported, and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests were used.

There were no significant differences in anterior humeral-capitellar line by bone age group or by sex. There were no significant differences in radiocapitellar alignment by bone age group, although the differences based on sex approached significance (male: 2% anterior, 98% middle, 0% posterior; female: 9% anterior, 89% middle, 2% posterior; p=.061).

When assessing continuous bone age with each of the continuous lateral radiograph measurements within the adolescent bone age group, increasing bone age was associated with an increase in anterior angulation of articular surface of distal humerus (ρ = .218, p=.015) and greater sigmoid notch circle (ρ = .475, p<.001). Increasing bone age was associated with a decrease in olecranon-coronoid angle (ρ = −.179, p=.046).

Reliability

Inter-rater reliabilities (ICC for quantitative variables, kappa for categorical variables) are presented in Table 4. Substantial inter-rater reliability was observed for carrying angle, articular surface angle, trochlear sulcus depth, lateral ridge height, trochleocapitellar sulcus depth, and olecranon-coronoid angle. Moderate inter-rater reliability was observed for trochlear notch angle and subjective bump type assessment. Fair inter-rater reliability was observed for radial neck shaft angle, Baumann angle, and anterior humeral line. Poor to slight inter-rater reliability was observed for anterior angulation of articular surface, sigmoid notch coverage, and radial-capitellar line. Intra-rater reliabilities are also presented in Table 4. However, we have not attempted to classify the magnitude of agreement because intra-rater reliability was assessed on just 18 subjects; thus, confidence intervals for intra-rater reliability measurements are wide.

Table 4.

Reliability of Radiographic Measures

| Measurements | Inter-rater reliabilitya | Intra-rater reliability for Rater 1b | Intra-rater reliability for Rater 2b | Intra-rater reliability for Rater 3b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous variables ICC (95% CI) | ||||

| Carrying angle | .80 (.75 – .84) | .91 (.77 – .97) | .83 (.59 – .93) | .92 (.80 – .97) |

| Articular surface angle | .64 (.57 – .71) | .84 (.62 – .94) | .80 (.53 – .92) | .76 (.47 – .90) |

| Trochlear sulcus depth | .80 (.75 – .84) | .83 (.59 – .93) | .58 (.14 – .83) | .85 (.63 – .94) |

| Lateral ridge height | .78 (.72 –.82) | .84 (.62 – .94) | .70 (.32 – .88) | .77 (.49 – .91) |

| Trochleocapitellar sulcus depth | .77 (.72 – .82) | .88 (.70 – .95) | .71 (.34 – .89) | .82 (.59 – .93) |

| Olecranon-coronoid angle | .72 (.66 – .78) | .83 (.61 – .93) | .87 (.69 – .95) | .79 (.52 – .92) |

| Trochlear notch angle | .55 (.46 – .62) | .27 (−.21 – .65) | .29 (−.19 – .66) | .62 (.23 – .84) |

| Radial neck shaft angle | .37 (.28 – .47) | .63 (.24 – .84) | .47 (.01 – .76) | .39 (−.08 – .72) |

| Baumann angle | .37 (.13 – .60)c | - d | - d | - d |

| Anterior angulation of articular surface | .05 (−.02 – .13) | .37 (−.11 – .70) | −.30 (−.67 – .18) | .11 (−.37 – .54) |

| Sigmoid notch coverage (degrees) | .12 (.03 – .21) | .17 (−.31 – .58) | .77 (.47 – .91) | .61 (.21 – .83) |

| Categorical variables Kappa (95% CI) | ||||

| “Bump” type | .45 (.39 – .51) | .68 (.39 – .97) | .60 (.25 – .95) | .80 (.52 – 1.0) |

| Radial-capitellar line | .14 (.06 – .22) | - e | - e | - e |

| Anterior humeral line | .36 (.27 – .44) | - f | - f | - f |

178 subjects, 3 raters

18 subjects

Inter-rater reliability for Baumann angle based on 28 subjects.

Intra-rater reliability for Baumann angle not calculated because only assessed on 3 subjects.

Cohen’s Kappa could not be calculated due to empty cells. Percent agreement was as follows: 94% for Rater 1, 89% for Rater 2, 100% for Rater 3.

Cohen’s Kappa could not be calculated due to empty cells. Percent agreement was as follows: 78% for Rater 1, 89% for Rater 2, 94% for Rater 3.

Discussion

This investigation demonstrates that some radiographic measurement techniques, such as carrying angle, articular surface angle, trochlear sulcus depth, lateral sulcus depth, and lateral ridge height, are substantially reliable (Table 4). These techniques demonstrated good to excellent reliability for both inter- and intra- rater assessment. Other commonly utilized measurement techniques, such as Baumann angle, radiocapitellar line, anterior humeral- capitellar line, and the anterior angulation of the distal humerus articular surface, were found to have poor reliability (Table 4). In one of the only other reports to mention reliability, Williamson, et al36 assessed Baumann angle in 114 children aged 2–13 years. They reported an average angle of 72 degrees with a standard deviation of 4 degrees, data very similar to our findings, using an overlay grid technique for measurement. Interestingly, they report that the intra-observer error was never more than 2 degrees and thought this to be a reliable measure; our findings of reliability were quite different although we used a different measurement technique. The poor reliability of these measures highlights the importance of a consistent and reliable measurement technique.

A brief discussion of two measurement techniques highlights the difficulties that are experienced with many of the traditional tools. The anterior humeral- capitellar line is most commonly utilized to assess sagittal alignment of the distal humerus in the setting of a supracondylar humerus fracture, and is typically described as normal when the anterior humeral line intersects the middle of the capitellum. Rogers, et al27 “confirmed” this relationship in a report based on only 35 radiographs (with 33 of these demonstrating an intersection with the middle of the capitellum). Recently, Herman, et al14 evaluated this relationship in patients less than 4 years of age compared with patients between four and nine years of age. Thirty radiographs in each age group were assessed and reliability was found to be moderate to substantial. The anterior humeral line intersected the capitellum in the middle third in most of the older group but in the anterior or middle third in the younger group.

Silberstein, et al29 in the manuscript appropriately entitled “Some Vagaries of the Capitellum,” suggest that the anterior humeral line should be drawn “parallel to the shaft of the visible humerus” and should pass “through the posterior half of the developing capitellum.” The authors remark that the curvature of the distal anterior humeral cortex makes the use of the anterior humeral line technique difficult and dispute that the line should pass in the center of the capitellum (as suggested by Rogers).26 While recognizing the difficulty caused by the gentle anterior bow of the distal humerus, we did utilize the anterior humeral line for this assessment as it is the most common technique and any measure utilizing the shaft is also vague. Eighty percent of elbows in this investigation demonstrated an intersection with the middle third of the capitellum, while almost all of the others intersected the posterior portion of the capitellum. The difficulty of this measurement technique is highlighted by the poor inter- and intra- observer reliability in our investigation.

Another commonly utilized elbow assessment technique is the carrying angle, or ulno- humeral angle. Carrying angle is a useful parameter in cases of distal humerus malunion and elbow instability, among other conditions. There are many previous reports on normal values 1–3, 5, 16, 21, 23, 33, 34, 37, 38; our data are similar to some of the previous reports as summarized in the Materials and Methods sections, but we did not find a significant difference based on age. While we did confirm a statistically distinct difference between males and females; the 2-degree higher carrying angle in females is a minimal clinical difference.

The difficulties in measurement are reflected in the introduction of several new measurement techniques in the literature. Simanovsky, et al30 described a new method for assessing the humerocondylar angle on the lateral radiograph in the skeletally immature patient; the authors measured the angle between the long axis of the humerus and a perpendicular to the physis. While there was a wide range of normal data and no assessment of reliability was performed, this technique seems a more reliable technique in assessing the anterior angulation of the distal humerus. Rettig et al25 provided additional objectivity to the assessment of the radial- capitellar line by using a circular template on the capitellum to directly quantify alignment of the radial head and the capitellum.

Likewise, 2 of the 14 measurements reported in this report are new: the articular surface assessment (Figure 2) and the depth of the greater sigmoid notch using circular templates. We believe that the subjective articular surface assessment of the elbow is important for a better understanding of elbow anatomy and may be helpful in assessing risk factors for the development of elbow arthrosis; it demonstrates good intra observer reliability although only moderate inter observer reliability. The implications of the variability in the morphology of the distal humerus articular surface are unknown; furthermore, there has been only one objective investigation to this end. Rettig et al25 recently evaluated the trochlear notch with a detailed assessment of the length, depth and width of its facets in an effort to associate morphological changes with the development of arthrosis. The implications of prominence of the lateral ridge and depths of the trochlear and trochleocapitellar sulci are currently unknown.

The other new technique utilized a manual templating process to assess the greater sigmoid notch, a somewhat arduous process that may be best suited for research purposes. Additionally, it was not a particularly reliable instrument. However, susceptibility to dislocation of the ulnohumeral joint is multifactorial and the precise role of the depth of the greater sigmoid notch is uncertain. There is not a straightforward radiographic method to assess the depth of the greater sigmoid notch, a possible contributing factor for elbow dislocations. Previously reported data for “coronoid height”, for example, measure retroversion of the proximal ulna and do not give any information about relative depth of the greater sigmoid notch. Other investigations have attempted to more accurately assess coronoid height20 but we found these techniques difficult. While this technique has limitations, it has the potential to help progress our objective understanding of the radiographic anatomy of the elbow.

There are several weaknesses to this investigation. First, we utilized printed, not digital, radiographs as we believe this remains the most common method for clinical assessment. Digital measurements may be more precise and offer a more straightforward technique for some measures. Second, we used plain radiographs to assess the adolescent elbow, recognizing that the youngest children in this series continue to have a significant cartilaginous contribution to the elbow anatomy. Most notably, this may affect our assessment of olecranon- coronoid angle and our subjective assessment of articular contour. Nonetheless, given the fact that most clinical assessments are based on plain radiographs, we feel our techniques are reasonable. Finally, standardization of radiographic technique affects measurement precision. Our orthopaedic- only radiology technicians were aware of the nature of this investigation and worked to provide standardized films. However, the radiographs of 17 subjects (10%) were flagged due to imprecise standardization of radiographic technique; these were included in our assessment as the measurement values did not deviate notably from average measures.

Conclusion

The radiographic assessment of the adolescent and young adult elbow is challenging due to a lack of objective, reliable measurement tools and the cartilage of the skeletally immature elbow. This investigation confirms the variability in reliability of commonly utilized assessment tools, an important consideration for both clinical care and research considerations. Most measurements were consistent between males and females and across the age spectrum; even statistically significant differences may not be clinically important. The new assessment of the distal humerus articular surface (both subjective and objective assessments) demonstrated an increased contour with maturity. The importance of the contour of the distal humerus articular surface bears further investigation as one variable to consider in adolescent and adult elbow pathology.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This publication was made possible by Grant Number UL1 RR024992 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the NCRR or NIH.

Footnotes

IRB Approval: Washington University School of Medicine, Human Research Protection Office, Study # 07-0640, Approval Date: 8/14/2008

Financial Disclaimer: None. No financial biases exist.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Atkinson W, Elftman H. The carrying angle of the human arm as a secondary sex character. Anatomy. 1945;91:45. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balasubramanian P, Madhuri V, Muliyil J. Carrying angle in children: a normative study. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2006;15:37–40. doi: 10.1097/2F01202412-200601000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baughman FA, Jr, Higgins JV, Wadsworth TG, Demaray MJ. The carrying angle in sex chromosome anomalies. Jama. 1974;230:718–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumann E. Beitrage zur Kenntnis der Frakturen am Ellbogengelenk. Unter besonderer Berucksichtigung der Spatfolgen. Allgemeines und Fractura supra condylica. Beitr F Klin Chir. 1929;146:1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beals RK. The normal carrying angle of the elbow. A radiographic study of 422 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976:194–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brodeur AE, Silberstein MJ, Graviss ER. Radiology of the Pediatric Elbow. Hall Medical Publishers; 1981. (book ref only - no specific chapter/page#) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng JC, Wing-Man K, Shen WY, Yurianto H, Xia G, Lau JT, et al. A new look at the sequential development of elbow-ossification centers in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998;18:161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Arienzo M, Innocenti M, Pennisi M. The treatment of supracondylar fractures of the humerus in childhood (cases and results) Arch Putti Chir Organi Mov. 1983;33:261–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dodge HS. Displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children--treatment by Dunlop's traction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:1408–1418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans EM. Rotational deformity in the treatment of fractures of both bones of the forearm. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1945;27:373. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fick DS, Lyons TA. Interpreting elbow radiographs in children. Am Fam Physician. 1997;55:1278–1282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frick MA. Reprint of imaging of the elbow: a review of imaging findings in acute and chronic traumatic disorders of the elbow. J Hand Ther. 2007;20:186–200. doi: 10.1197/j.jht.2007.02.001. quiz 201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greulich WW, Pyle SI. Radiographic Atlas of Skeletal Development of the Hand and Wrist. Stanford University Press; 1959. (book ref only - no specific chapter/page#) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herman MJ, Boardman MJ, Hoover JR, Chafetz RS. Relationship of the anterior humeral line to the capitellar ossific nucleus: variability with age. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2188–2193. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson TR, Steinback LS. Essentials of Musculoskeletal Imaging. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgery; 2004. (book ref only - no specific chapter/page#) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keats TE, Teeslink R, Diamond AE, Williams JH. Normal axial relationships of the major joints. Radiology. 1966;87:904–907. doi: 10.1148/87.5.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keenan WN, Clegg J. Variation of Baumann's angle with age, sex, and side: implications for its use in radiological monitoring of supracondylar fracture of the humerus in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996;16:97–98. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199601000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lennon RI, Riyat MS, Hilliam R, Anathkrishnan G, Alderson G. Can a normal range of elbow movement predict a normal elbow x ray? Emerg Med J. 2007;24:86–88. doi: 10.1136/emj.2006.039792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matzon JL, Widmer BJ, Draganich LF, Mass DP, Phillips CS. Anatomy of the coronoid process. J Hand Surg [Am] 2006;31:1272–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrey BF, Chao EY. Passive motion of the elbow joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58:501–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrissey R, Weinstein S. Lovell & Winter's Pediatric Orthopaedics. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2001. (book ref only - no specific chapter/page#) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Potter HP. The Obliquity of the Arm of the Female in Extension. The Relation of the Forearm with the Upper Arm in Flexion. J Anat Physiol. 1895;29:488–491. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Purkait R. Measurements of ulna--a new method for determination of sex. J Forensic Sci. 2001;46:924–927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rettig LA, Hastings H, 2nd, Feinberg JR. Primary osteoarthritis of the elbow: lack of radiographic evidence for morphologic predisposition, results of operative debridement at intermediate follow-up, and basis for a new radiographic classification system. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogers LF, Malave S, Jr, White H, Tachdjian MO. Plastic bowing, torus and greenstick supracondylar fractures of the humerus: radiographic clues to obscure fractures of the elbow in children. Radiology. 1978;128:145–150. doi: 10.1148/128.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogers LF, Rockwood CA., Jr Separation of the entire distal humeral epiphysis. Radiology. 1973;106:393–400. doi: 10.1148/106.2.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandegard E. Fracture of the lower end of the humerus in children - treatment and end results. Acta Chir Scandinavica. 1943;89:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silberstein MJ, Brodeur AE, Graviss ER. Some vagaries of the capitellum. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61:244–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simanovsky N, Lamdan R, Hiller N, Simanovsky N. The measurements and standardization of humerocondylar angle in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28:463–465. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e31817445ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith FM. Children's elbow injuries: fractures and dislocations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1967;50:7–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Storen G. Traumatic dislocation of the radial head as an isolated lesion in children; report of one case with special regard to roentgen diagnosis. Acta Chir Scand. 1959;116:144–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tukenmez M, Demirel H, Percin S, Tezeren G. [Measurement of the carrying angle of the elbow in 2,000 children at ages six and fourteen years] Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2004;38:274–276. No doi. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiland A. In: The elbow and its disorders. 3. Morrey B, editor. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000. pp. 13–42. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiland A. In: The elbow and its disorders. 3. Morrey B, editor. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000. pp. 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williamson DM, Coates CJ, Miller RK, Cole WG. Normal characteristics of the Baumann (humerocapitellar) angle: an aid in assessment of supracondylar fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992;12:636–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yilmaz E, Karakurt L, Belhan O, Bulut M, Serin E, Avci M. Variation of carrying angle with age, sex, and special reference to side. Orthopedics. 2005;28:1360–1363. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20051101-16. No doi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zimmerman NB. Clinical application of advances in elbow and forearm anatomy and biomechanics. Hand Clin. 2002;18:1–19. doi: 10.1016/S0749-0712(02)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]