Abstract

Evolving resistance to artemisinin-based compounds threatens to derail attempts to control malaria. Resistance has been confirmed in western Cambodia, has recently emerged in western Thailand, but is absent from neighboring Laos. Artemisinin resistance results in reduced parasite clearance rates (CR) following treatment. We used a two-phase strategy to identify genome region(s) underlying this ongoing selective event. Geographical differentiation and haplotype structure at 6,969 polymorphic SNPs in 91 parasites from Cambodia, Thailand and Laos identified 33 genome regions under strong selection. We screened SNPs and microsatellites within these regions in 715 parasites from Thailand, identifying a selective sweep on chr 13 that shows strong association (P=10-6-10-12) with slow CR, illustrating the efficacy of targeted association for identifying the genetic basis of adaptive traits.

Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) are first line treatment in nearly all malaria endemic countries (1) and central to the current success of global efforts to control and eliminate Plasmodium falciparum malaria (2). Resistance to artemisinin (ART) in P. falciparum has been confirmed in SE Asia (3), raising concerns that it will spread to sub-Saharan Africa, following the path of chloroquine and anti-folate resistance (4). ART-resistance results in reduced CR following treatment (Fig. 1A) and is principally due to parasite genetics, which determines 58% and 64% of the variance in parasite CR in western Cambodia and western Thailand respectively (5, 6). The resistance mechanism is unknown but reduced killing of “ring”-stage parasites (7) and quiescence have been implicated (8). The genetic basis is likely to be simple. A single mutation in the ubp1 gene confers ART resistance in the P. chabaudi mouse malaria model (9). Similarly resistance to other antimalarials in P. falciparum involves single major gene effects or is oligogenic (10).

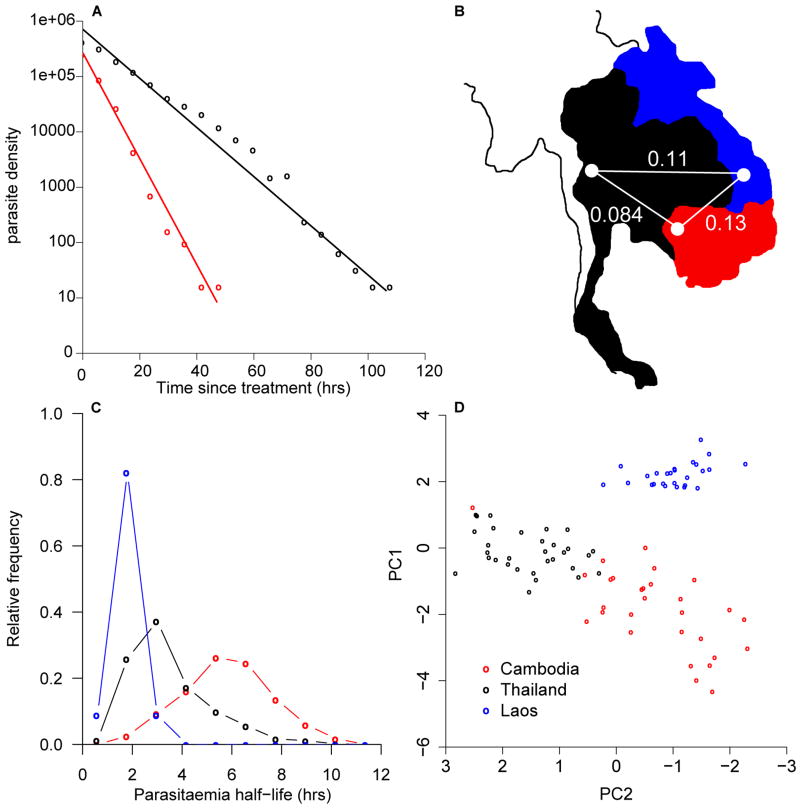

Figure 1.

Phenotypic and genetic differentiation between South-East Asian parasites. A) Patterns of parasite clearance from two Thai patients (black, slow CR/red fast CR) following treatment. B) FST between locations for 5,662 SNPs with MAF > 5%. C) Clearance half lives from Laos (blue; n=44), Cambodia (red; n=64), and Thailand (black; n=3,202) and D) PCA of parasites using 1,770 SNPs with MAF >5% and no missing data.

Cross-population genomic comparisons offer a means to identify putative targets of natural selection (11-14). Targeted association analyses of genome regions under selection can then be used to directly identify the genetic basis of adaptive traits (13, 14), minimizing the multiple-testing penalties constraining standard genome-wide association studies. We compared three neighboring SE Asian P. falciparum populations (Laos, Thailand and Cambodia) with low levels of genetic differentiation (Fig. 1B), but differences in CR following ART-treatment (Fig. 1C), to detect recent selective sweeps that may underlie resistance. Parasites from Laos are cleared rapidly (median -log(CR) = 1; half-life of parasite decline (2 hours)), parasites from western Cambodia clear slowly (median -log(CR) 2.15, half-life 6 hours) and parasites from western Thailand show a wide range of clearance (median -log(CR) 1.4, half-life 3 hours). CR distributions are significantly different between all locations (Thai-Cambodia, D=0.58, P<0.001, Thai-Laos, D=0.68, P<0.001, Cambodia-Laos, D=0.93, P<0.001, two-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov test).

We genotyped 91 genetically-unique single clone parasites (27 Laos, 30 Cambodian, 34 Thai) by hybridization to a custom Nimblegen genotyping array that scores SNPs (1 SNP/500bp) and copy number variation (CNV) (15, 16). Principal components analysis (PCA) and global FST values confirmed low but significant differentiation between the three populations (Fig. 1, B and D). We characterized CNV across the three populations, identifying 78 common CNVs (minor allele frequency (MAF) > 5%) containing 209 genes (16).

For each SNP (MAF >5%, n=6,969) we calculated two statistics to identify genome regions under strong selection for our three populations, measuring differentiation in haplotype structure (XP-EHH (17)) and allele frequency (FST) and classifying selected regions using a 10kb sliding window approach (16). (Fig. 2, fig. S1). Thirty-three non-overlapping regions, comprising 2.4% of the 23Mb genome, reached this criterion in one or more population, and were ranked by the proportion of significant tests (table S1).

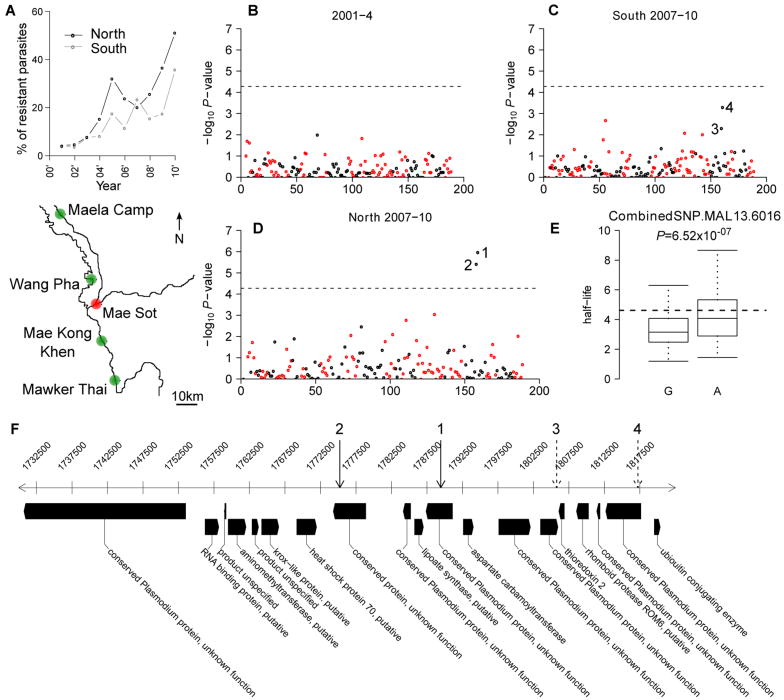

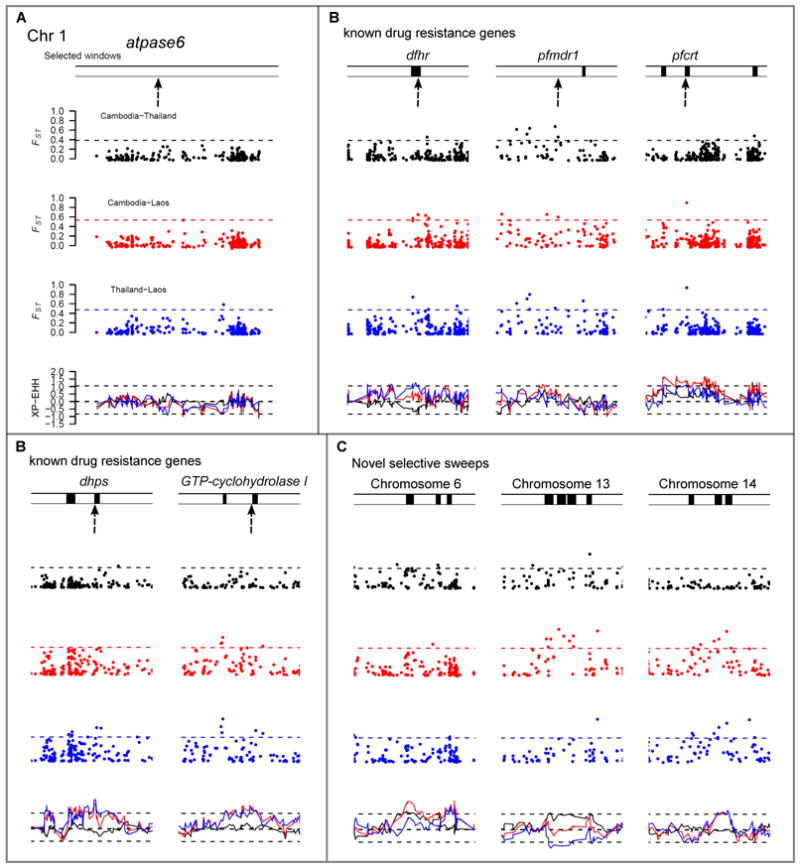

Figure 2.

Evidence for selection. Plots show FST and XP-EHH for each SNP (n=6,969) in pair-wise comparisons of countries. Dashed lines represent the 1% level from the genomic empirical distribution. Significant windows are shown by black bars above each plot. Red = Cambodia vs. Laos, blue = Thailand vs. Laos, black = Cambodia vs. Thailand. A) Chromosome 1. No evidence of selection surrounding atpase6. B) Patterns of selection surrounding five known drug resistance genes (marked by arrows). C) Three loci putatively under selection.

Known antimalarial resistance genes accounted for 10/33 genome regions. Three genes (pfcrt, dhps, dhfr) were identified directly, while GTP-cyclohydrolase I showed evidence of selection within 5kb (Fig. 2B). pfmdr1 was not identified most likely because the amplicon containing pfmdr1 has multiple origins (18). An additional 23 genome regions showed strong signatures of selection (table S1 and fig. S1). Three regions, on chr 6, 13 and 14, were significant at multiple adjacent windows and ranked eighth, first and second respectively (table S1, Fig. 2C). We did not observe evidence for selection at two proposed candidate loci, atpase6 (Fig. 2A) (19) or PArt (20). Two CNVs showed strong differentiation (FST>0.4). A chr 12 CNV containing GTP-cyclohydrolase I (FST=0.6; Thailand vs. Laos) is driven by anti-folate treatment (21) while a deletion of surfin4.1 (FST=0.51; Cambodia vs. Laos) is not a strong candidate as this is present in >20% of Lao infections and in African samples. The 78 CNVs did not overlap with the 33 regions under selection and were not considered further.

We examined the association of each of these 33 regions with parasite CR in an independent parasite population. Targeted association allows us to exploit an extensive archive of bloodspot DNA samples from Thai patients with detailed (6-hourly) CR data. Between 2001 and 2010, 3,202 patients with uncomplicated malaria were treated with ART in four clinics on the Thai-Burmese border (5). The proportion of parasites with slow clearance (-log(CR)>1.89) rose from <5% in 2001 to >50% in 2010, with resistance spreading more rapidly north of Mae Sot compared to the south (Fig. 3A). In 1,689 patients with available bloodspots we identified (fig. S4) all genetically-unique infections containing a single parasite clone (n=715, 417 from the north, 96 from 2001-4, 321 from 2007-10, and 298 from the south, 121 from 2001-4, 177 from 2007-10). We genotyped 90 SNPs targeting the 33 selected regions, 4 SNPs in atpase6 and pfmdr1 (table S2) in addition to the 93 genome-wide control SNPs genotyped previously (5, 16).

Figure 3.

Association testing. A) Study sites on the Thai-Burma border. Northern populations were Maela Camp and Wang Pha and southern populations Mae Kong Khen and Mawker Thai. Clearance rate between 2001-2010 has declined (shown above the map). The y-axis shows the percentage of parasites with –log(clearance rate) > 1.89. B-D) Association of 94 SNPs from selected regions (black) and 93 genome-wide SNPs (red). Two neighboring SNPs in the northern population from 2007-2010 showed strong association with clearance rate (denoted 1 and 2). E) Boxplot of the clearance rate for each allele of SNP 1. F) The chromosomal context surrounding these SNPs.

There were no associations in 2001-4 (Fig. 3B) or at either pfmdr1 or atpase6. Two adjacent SNPs (14kb apart) on chr 13 showed strong association (P=5.0×10-6-6.5×10-7, Fishers' exact test) in the north (2007-10, Fig. 3D). The strongest signals of association in the 2007-10 southern samples lay adjacent to these SNPs (Fig. 3C). Quantile-quantile plots indicate moderate inflation of association P-values (inflation factor = 1.24-1.27, fig. S2) but the two SNPs remain significantly associated following adjustment for this inflation.

We fine-mapped this region using 19 microsatellite markers spanning 550kb surrounding the strongest association signal in 417 northern Thai, 88 Lao and 83 Cambodian parasites. Four microsatellites spanning ∼35kb showed strong association with CR (P= 2.8×10-9-6.6×10-12; χ2 test) in 2007-2010 but no association in 2001-4 (Fig. 4A). This analysis uses a threshold to define “resistant” parasites. Reanalysis of quantitative CR data using a general linear model (22) confirms the results of the categorical χ2 test (P=1.1×10-5-1.6×10-10), and use of a more stringent threshold (-log(CR) > 2.19) for defining resistance boosted maximal significance to P=9×10-16. Alleles at the marker showing maximal association show a three-fold difference in CR (Fig. 4D).

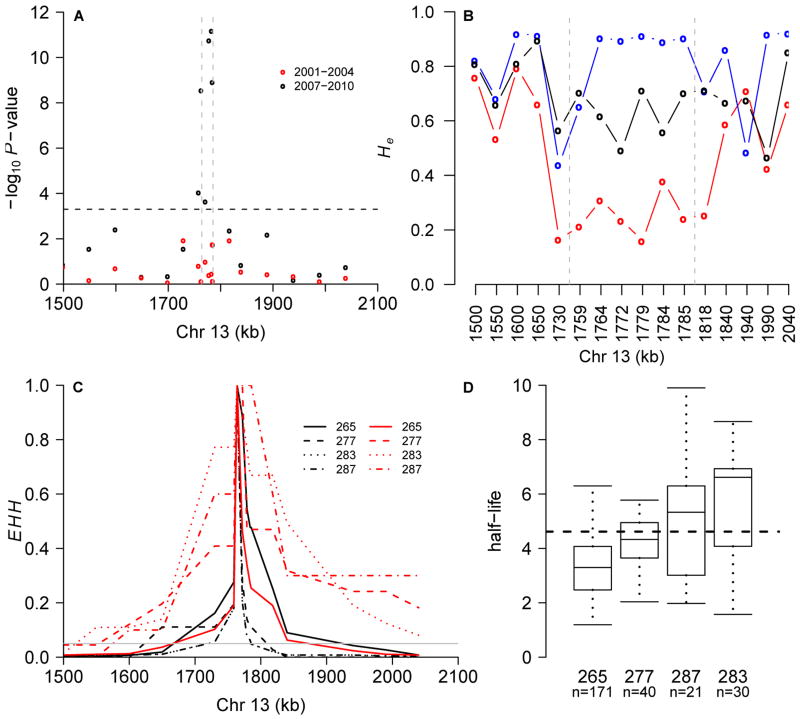

Figure 4.

Fine mapping using 19 microsatellites. A) Association P-values from the early (2001-4; red dots) and late (2007-10; black dots) periods in northern Thai population. Bonferroni-correction threshold is shown by dashed line. B) Comparison of He in Thailand, Laos and Cambodia. C) EHH surrounding a microsatellite (position 1,763,950) in slow (half-life>4.6 hours) and fast (half-life<2.3 hours) clearing parasites. D) Phenotypic distribution at this locus in 2007-10 (P=4×10-12).

Assuming a recent selective sweep we expect reduced allelic variation in Cambodia and Thailand relative to Laos. We observed maximal diversity reduction in Cambodia (expected heterozygosity (He) = 0.24 (± 0.07 1.s.d)) at eight markers spanning 105 kb (Fig. 4B). In contrast, diversity is high across this region in Laos (He= 0.79 (± 0.17 1.s.d)) while Thai parasites showed intermediate levels of diversity (He= 0.63 (± 0.09 1.s.d)). There was no separation between highly resistant and sensitive parasites, perhaps due to multiple origins of resistance alleles or evolution from standing variation (23). Analysis of haplotype structure provides strong evidence for recent selection in Thailand (Fig. 4C). Extended haplotype homozygosity (EHH) decays to background levels (0.05) over 99kb (range = 24 to 190kb) in sensitive (-log(CR)<1.3) parasites while in resistant (-log(CR)>1.89) parasites decay to background levels is over 375kb (range = 140 to >550kb). Permutation testing reveals this difference to be highly significant (P=0.0003, (16) and fig. S5).

Using a general linear model (22), we estimated that 22.5% of the variation in CR is determined by this region in 2007-10. Given the heritability of CR in this population (64% (5)) we conservatively estimate that this locus explains at least 35.2% (22.5/64) of the heritable component of CR, suggesting it is a major determinant of ART-resistance.

Within this 35kb region there are multiple candidate ART-resistance genes (table S4). These include lipoate synthase (lipoic acid salvage/biosynthesis), aminomethyltransferase (glycine cleavage pathway) and hsp70 (stress response/molecular chaperone). We sequenced the coding regions of six of the seven genes (18,747 bp) in eight Lao, eight Cambodian, and 24-31 Thai parasites (fig. S3). Six non-synonymous, derived mutations in three/six genes are at high frequency in ART resistant populations including SNPs 1 and 2 (Fig. 3F, table S4). However, these were present in parasites from SE Asia prior to the origin of ART-resistance suggesting that they are associated, but do not directly underlie CR, and that non-coding regulatory mutations may be involved. Analysis of transcriptional changes in resistant lines offers a means to further prioritize genes for follow up. Three genes within the region show significant changes in transcript levels during at least one life-cycle stage in ART- resistant lines profiled in a recent transcriptomic study ((24), table S4).

Spread of ART-resistant parasites would be catastrophic for malaria control. We have shown that a strongly selected region on chr 13, containing several candidate genes, explains a large proportion of variation in CR. Future functional dissection of loci within this region will be dependent on the development of laboratory assays which replicate the CR phenotype. The mapping approach we have used - targeted association of selected genome regions - has broad utility for researchers wishing to map variants responsible for traits under strong recent positive selection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Clinical work was funded by the Wellcome Trust. Molecular work was funded by NIH (R01 AI048071/AI075145) in facilities constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Program Grant Number C06 RR013556 from the NCRR. We thank patients and staff who contributed to data collection in Thailand, Cambodia (Chea Nguon, Char Meng Chuor, Duong Socheat) and Laos (Maniphone Khanthavong, Odai Chanthongthip, Bongkot Soonthornsata, Tiengkham Pongvongsa, Samlane Phompida, Bouasy Hongvanthong), Kathy Burgoine, Pratap Singhasivanon, Pascal Ringwald, Mark Zlojutro Kos and Joanne Currans' lab.

Microarray data have been submitted to NCBI GEO under accession numbers GSM818073-GSM818239.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References and Notes

- 1.White NJ. Qinghaosu (artemisinin): the price of success. Science. 2008;320:330. doi: 10.1126/science.1155165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eastman RT, Fidock DA. Artemisinin-based combination therapies: a vital tool in efforts to eliminate malaria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:864. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dondorp AM, et al. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:455. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roper C, et al. Intercontinental spread of pyrimethamine-resistant malaria. Science. 2004;305:1124. doi: 10.1126/science.1098876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phyo AP, et al. Emergence of artemisinin resistant malaria on the western border of Thailand. Lancet. 2012 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60484-X. accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson TJ, et al. High heritability of malaria parasite clearance rate indicates a genetic basis for artemisinin resistance in western Cambodia. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1326. doi: 10.1086/651562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saralamba S, et al. Intrahost modeling of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006113108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tucker MS, Mutka T, Sparks K, Patel J, Kyle DE. Phenotypic and Genotypic Analysis of In Vitro-Selected Artemisinin-Resistant Progeny of Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:302. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05540-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunt P, et al. Experimental evolution, genetic analysis and genome re-sequencing reveal the mutation conferring artemisinin resistance in an isogenic lineage of malaria parasites. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:499. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson T, Nkhoma S, Ecker A, Fidock D. How can we identify parasite genes that underlie antimalarial drug resistance? Pharmacogenomics. 2011;12:59. doi: 10.2217/pgs.10.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson TJ, et al. Geographical distribution of selected and putatively neutral SNPs in Southeast Asian malaria parasites. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:2362. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewontin RC, Krakauer J. Distribution of gene frequency as a test of the theory of the selective neutrality of polymorphisms. Genetics. 1973;74:175. doi: 10.1093/genetics/74.1.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yi X, et al. Sequencing of 50 human exomes reveals adaptation to high altitude. Science. 2010;329:75. doi: 10.1126/science.1190371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simonson TS, et al. Genetic evidence for high-altitude adaptation in Tibet. Science. 2010;329:72. doi: 10.1126/science.1189406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan JC, et al. An optimized microarray platform for assaying genomic variation in Plasmodium falciparum field populations. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R35. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-4-r35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Materials and methods are available as supplementary material on Science Online

- 17.Sabeti PC, et al. Genome-wide detection and characterization of positive selection in human populations. Nature. 2007;449:913. doi: 10.1038/nature06250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nair S, et al. Recurrent gene amplification and soft selective sweeps during evolution of multidrug resistance in malaria parasites. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:562. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jambou R, et al. Resistance of Plasmodium falciparum field isolates to in-vitro artemether and point mutations of the SERCA-type PfATPase6. Lancet. 2005;366:1960. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67787-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deplaine G, et al. Artesunate tolerance in transgenic Plasmodium falciparum parasites overexpressing a tryptophan-rich protein. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:2576. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01409-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kidgell C, et al. A systematic map of genetic variation in Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e57. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bradbury PJ, et al. TASSEL: software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2633. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Przeworski M, Coop G, Wall JD. The signature of positive selection on standing genetic variation. Evolution. 2005;59:2312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mok S, et al. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum is associated with an altered temporal pattern of transcription. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:391. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.