Abstract

Background

Target values for cardiovascular risk factors in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) are stated in guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. We studied secular trends in risk factors over a 12-year period among CHD patients in the region of Münster, Germany.

Methods

The cross-sectional EUROASPIRE I, II and III surveys were performed in multiple centers across Europe. For all three, the Münster region was the participating German region. In the three periods 1995/96, 1999/2000, and 2006/07, the surveys included (respectively) 392, 402 and 457 ≤ 70-year-old patients with CHD in Münster who had sustained a coronary event at least 6 months earlier.

Results

The prevalence of smoking remained unchanged, with 16.8% in EUROASPIRE I and II and 18.4% in EUROASPIRE III (p=0.898). On the other hand, high blood pressure and high cholesterol both became less common across the three EUROASPIRE studies (60.7% to 69.4% to 55.3%, and 94.3% to 83.4% to 48.1%, respectively; p<0.001 for both). Obesity became more common (23.0% to 30.6% to 43.1%, p<0.001), as did treatment with antihypertensive and lipid-lowering drugs (80.4% to 88.6% to 94.3%, and 35.0% to 67.4% to 87.0%, respectively; p<0.001 for both).

Conclusion

The observed trends in cardiovascular risk factors under-score the vital need for better preventive strategies in patients with CHD.

Patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) have higher overall and cardiovascular mortality than the general population (1). They can decrease the risk of suffering a further CHD event by

Lowering their blood pressure (2)

Changing their eating habits (5)

Increasing their physical activity (6)

The regularly updated guidelines of the Joint European Societies promulgate evidence-based recommendations for the prevention of cardiovascular diseases in clinical practice (7, e3– e5). In 1995/96 and 1999/2000 the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) carried out the surveys EUROASPIRE I and II (EUROpean Action on Secondary Prevention through Intervention to Reduce Events) to examine the implementation of these recommendations in CHD patients. EUROASPIRE is a multicenter study to evaluate secondary prevention in CHD patients in Europe. To this end, cross-sectional surveys of hospital patients with CHD were conducted in nine (EUROASPIRE I) and 15 (EUROASPIRE II) regions across Europe. EUROASPIRE I and II showed inadequate secondary prevention of CHD in Europe (8, 9) and found no essential changes in risk and lifestyle factors (10). These overall findings also applied to the area around Münster, the German study region in EUROASPIRE I and II (11, 12).

Given the importance of cardiovascular diseases for the population, these results prompted the ESC to carry out a third EUROASPIRE survey of CHD patients, extended to 22 European regions (13, 14). The aim of the study described here was to investigate the temporal trends of cardiovascular risk factors in CHD patients in the Münster region, using the data from all three EUROASPIRE surveys.

Methods

Study population

The administrative region of Münster, with 2.6 million inhabitants, was selected as the German EUROASPIRE study region, and the same hospitals and departments took part in all three EUROASPIRE surveys: the Department of Cardiology and Angiology and the Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, both at the University Hospital of Münster, and the Department for Internal Medicine III, at St. Franziskus Hospital Münster (14). Patients ≤ 70 years of age at the time of one of the following coronary events were included in the survey:

Acute myocardial infarction

Acute myocardial ischemia

Elective or emergency percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)

Elective or emergency aortocoronary bypass surgery (ACB)

The patients were identified retrospectively by their International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnosis codes: ICD-9 410, ICD-9 411, and ICD-9 413 in EUROASPIRE I and II, ICD-10 121 and ICD-10 120 in EUROASPIRE III. For a patient to be eligible, the coronary event had to have taken place at least 6 months before enrollment in the study. Participation in EUROASPIRE was preceded by full explanation and written consent, and the studies were approved by the local ethics committee.

Data acquisition

The study participants were questioned and examined from September 1995 to February 1996 (EUROASPIRE I), from September 1999 to January 2000 (EUROASPIRE II), and from September 2006 to January 2007 (EUROASPIRE III). The interviews and examinations were carried out by specially trained study assistants. Standardized methods and calibrated and validated instruments were used for all measurements, and standardized procedures were followed. For measurement of body weight and height, the patient stood wearing light clothing and no shoes. Blood pressure was measured with the patient sitting erect, using an automatic digital sphygmomanometer. The patient’s waist size was measured at the horizontal midpoint between the lower margin of the costal arch and the upper margin of the iliac crest. A sample of venous blood was taken for determination of total cholesterol at the central study laboratory. The carbon monoxide content of exhaled air was measured with a Smokerlyzer. Smoking status and presence or absence of diabetes mellitus were recorded. Intake of cardioprotective medications at the time of the interviews was determined from the list of medications provided by the patient.

The instruments used for measurement varied among the three EUROASPIRE surveys. For this reason, validation studies were carried out and corrections were made to the blood pressure measurements in EUROASPIRE I and II and the cholesterol measurements in EUROASPIRE I:

Systolic blood pressure: -0.95 mmHg

Diastolic blood pressure: +1,42 mmHg

Total cholesterol: multiplication factor of 1.13 (14)

Risk factors

Cardiovascular risk factors were defined as follows:

Smoking: patient’s statement and/or >10 ppm carbon monoxide in exhaled air

High blood pressure: systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg (≥130 mmHg) and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg (≥80 mmHg) in non-diabetics (diabetics)

High cholesterol: total cholesterol ≥175 mg/dL

Diabetes mellitus: patient’s statement of diagnosis of diabetes mellitus by a physician

Overweight: body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2

Obesity: BMI ≥30 kg/m2

Abdominal overweight: waist measurement ≥80 cm but <88 cm in women and ≥94 cm but <102 cm in men

Abdominal obesity: waist measurement ≥88 cm in women and ≥102 cm in men

Statistical methods

In accordance with the international study protocol, around 400 patients were included in each of the three EUROASPIRE surveys in order to be able to estimate prevalences with a precision of 5% with a confidence interval of 95%. All study participants for whom data and measurements were available for the variables concerned were included in the statistical analysis. Presentation of the patients’ characteristics at the time of interview and examination was descriptive according to the EUROASPIRE survey. A linear regression model with age, sex, and diagnostic group as independent variables was used to compare continuous variables between EUROASPIRE I, II, and III. Categorical variables were compared between EUROASPIRE I, II, and III in a binomial regression model adjusted for age, sex, and diagnostic group. The software package Statistical Analysis System Version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

The number of CHD patients identified from hospital records was 524, 684, and 645 for EUROASPIRE I, II, and III respectively. Of these, respectively 16, 26, and 23 had already died; 464, 604, and 555 were contacted; and 392, 402, and 457 took part in EUROASPIRE I, II and III. The mean age of the patients who participated in EUROASPIRE III was 60.0 (SD 7.8) years, somewhat higher than in EUROASPIRE I (58.6 [SD 7.9]) and II (59.5 [7.7]). The median interval between event and interview in EUROASPIRE I, II and III was 1.3 (interquartile 1.1–1.9), 1.5 (interquartile 1.2–1.9), and 1.1 (interquartile 0.9–1.4) years respectively.

The frequency of smoking varied hardly at all: 16.8% in both EUROASPIRE I and EUROASPIRE II, 18.4% in EUROASPIRE III (p = 0.898) (Figure, Table 1, eTable 1). The mean systolic blood pressure increased from 139.6 (SD 23.2) mmHg in EUROASPIRE I to 145.4 (SD 22.3) mmHg in EUROASPIRE II and decreased to 140.2 (SD 21.5) mmHg in EUROASPIRE III. The diastolic blood pressure showed a similar trend, with mean values of 86.6 (SD 10.8) mmHg, 88.8 (SD 12.1) mmHg, and 82.0 (SD 12.1) mmHg in EUROASPIRE I, II, and III respectively. There was no essential change in the prevalence of high blood pressure between EUROASPIRE I (60.7%) and EUROASPIRE III (55.3%; p = 0.246). The mean total cholesterol went down from 233.9 (SD 43.4) mg/dL in EUROASPIRE I to 213.7 (SD 42.0) mg/dL in EUROASPIRE II and sank further to 177.4 (SD 38.4) mg/dL in EUROASPIRE III. The frequency of high cholesterol values decreased from 94.3% in EUROASPIRE I to 83.4% and 48.1% in EUROASPIRE II and EUROASPIRE III respectively (p <0.001).

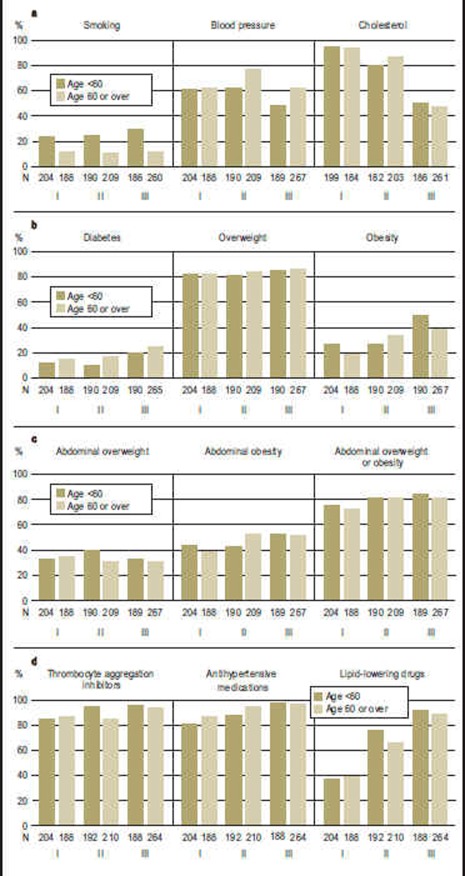

Figure.

Frequency (%) of smoking, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes mellitus, overweight, obesity, abdominal overweight, abdominal obesity, and treatment with cardioprotective medications among CHD patients from the Münster region who took part in EUROASPIRE I, II and III.

N:

Absolute number of patients per group

Smoking:

Patient’s statement and/or >10 ppm carbon monoxide in exhaled air

Blood pressure:

Blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg (≥130/80 mmHg) in non-diabetics (diabetics)

Cholesterol:

Total cholesterol ≥175 mg/dL

Diabetes:

Patient’s statement of diagnosis of diabetes mellitus by a physician

Overweight:

Body mass index ≥25 kg/m2

Obesity:

Body mass index ≥30 kg/m2

Abdominal overweight:

Waist measurement ≥80 cm but <88 cm in women, ≥94 cm but <102 cm in men

Abdominal obesity:

Waist measurement ≥88 cm in women and ≥102 cm in men

Thrombocyte aggregation inhibitors:

Aspirin, other thrombocyte aggregation inhibitors

Antihypertensive medications:

Beta blockers, calcium antagonists, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, diuretics, other antihypertensive medications

Lipid-lowering drugs:

Statins, other lipid-lowering drugs

Table 1. Comparison of risk factors, measurement results and medicinal treatment in CHD patients from the Münster region in EUROASPIRE I, II, and III.

| EUROASPIRE III vs. I | EUROASPIRE III vs. II | EUROASPIRE II vs. I | Total | |||||||

| Difference (95% CI) | p value | Difference (95% CI) | p value | Difference (95% CI) | p value | p value | ||||

| Risk factor (%) | ||||||||||

| Smoking*1 | +1.0 (-3.7 – +5.7) | 0.676 | +1.0 (-3.6 – +5.5) | 0.692 | +0.1 (-4.1 – +4.3) | 0.968 | 0.898 | |||

| High blood pressure*2 | -4.3 (-11.5 – +3.0) | 0.246 | -12.9 (-20.1 – -5.8) | <0.001 | +8.6 (+2.2 – +15.1) | 0.009 | < 0.001 | |||

| High cholesterol*3 | -42.8 (-49.4 – -36.2) | 0.001 | -33.0 (-39.6 – -26.5) | <0.001 | -9.7 (-15.1 – -4.4) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Diabetes mellitus*4 | +11.1 (+5.6 – +16.5) | 0.001 | +11.0 (+5.8 – +16.2) | <0.001 | +0.03 (-4.5 – +4.5) | 0.988 | < 0.001 | |||

| Overweight*5 | +4.4 (-1.0 – +9.7) | 0.109 | +4.0 (-1.4 – +9.5) | 0.146 | +0.3 (-4.9 – +5.6) | 0.898 | 0.225 | |||

| Obesity*6 | +21.8 (+15.0 – +28.5) | 0.001 | +13.4 (+6.5 – +20.3) | <0.001 | +8.3 (+2.3 – +14.4) | 0.007 | <0.001 | |||

| Abdominal overweight*7 | -1.6 (-8.5 – +5.3) | 0.649 | -2.0 (-8.9 – +5.0) | 0.575 | +0.4 (-6.1 – +6.8) | 0.906 | 0.843 | |||

| Abdominal obesity*8 | +12.9 (+5.5 – +20.3) | <0.001 | +5.6 (-1.7 – +13.0) | 0.132 | +7.3 (+0.6 – +14.0) | 0.034 | 0.003 | |||

| Measurement esults (mean) | ||||||||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | +0.63 (-2.66 – +3.92) | 0.708 | -4.84 (-8.10 – -1.59) | 0.001 | +5.47 (+2.42 – +8.52) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | -4.17 (-5.94 – -2.41) | <0.001 | -6.41 (-8.16 – -4.67) | <0.001 | +2.24 (+0.60 – +3.87) | 0.007 | <0.001 | |||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | -54.6 (-60.8 – -48.3) | <0.001 | –34.3 (-40.5 – -28.1) | <0.001 | -20.3 (-26.1 – -14.5) | 0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | +2.3 (+1.69 – +2.91) | <0.001 | +1.51 (+0.91 – +2.1) | <0.001 | +0.79 (+0.22 – +1.35) | 0.006 | <0.001 | |||

| Therapeutic control (%) | ||||||||||

| Control of blood pressure*9 | +4.8 (-2.9 – +12.6) | 0.224 | +15.2 (+7.7 – +22.7) | <0.001 | -10.4 (-17.4 – -3.4) | 0.004 | <0.001 | |||

| Control of cholesterol*10 | +36.6 (+26.5 – +46.8) | <0.001 | +27.2 (+18.7 – +35.7) | <0.001 | +9.5 (-0.4 – +19.3) | 0.059 | <0.001 | |||

| Medicinal treatment (%) | ||||||||||

| Thrombocyte aggregation inhibitors*11 | +6.5 (+2.0 – +11.0) | 0.005 | +3.0 (-1.2 – +7.1) | 0.162 | +3.5 (-1.2 – +8.3) | 0.145 | 0.013 | |||

| Antihypertensive medications*12 | +12.7 (+7.4 – +18.0) | <0.001 | +4.5 (-0.2 – +9.1) | 0.058 | +8.2 (+3.0 – +13.5) | 0.002 | <0.001 | |||

| Lipid-lowering drugs*13 | +48.6 (+42.2 – +55.0) | <0.001 | +15.4 (+9.2 – +21.6) | 0.001 | +33.0 (+26.7 – +39.7) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

The p values are from linear and binomial regression models and adjusted for age, sex, and diagnostic group.

*1Patient’s statement and/or >10 ppm carbon monoxide in exhaled air;

*2blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg (≥130/80 mmHg) in non-diabetics (diabetics);

*3total cholesterol ≥175 mg/dL;

*4patient’s statement of diagnosis of diabetes mellitus by a physician;

*5body mass index ≥ 25 kg/m 2;

*6body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m 2;

*7waist measurement ≥80 cm but <88 cm in women, ≥94 cm but <102 cm in men;

*8waist measurement ≥88 cm in women and ≥102 cm in men;

*9blood pressure <140/90 mmHg (<130/80 mmHg) in non-diabetics (diabetics) with antihypertensive medication;

*10total cholesterol <175 mg/dL in patients with lipid-lowering drugs;

*11aspirin, other thrombocyte aggregation inhibitors;

*12beta blockers, calcium antagonists, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, diuretics, other antihypertensive medications;

*13statins, other lipid-lowering drugs

eTable 1. Frequency (%) of smoking, high blood pressure and high cholesterol in CHD patients from the Münster region in EUROASPIRE I, II, and III.

| Smoking*1 | High blood pressure*2 | High cholesterol*3 | |||||||

| EUROASPIRE | EUROASPIRE | EUROASPIRE | |||||||

| I | II | III | I | II | III | I | II | III | |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| <60 | 45/204 (22.1) | 46/190 (24.2) | 54/186 (29.0) | 122/204 (59.8) | 116/190 (61.1) | 89/189 (47.1) | 188/199(94.5) | 145/182(79.7) | 92/186 (49.5) |

| ≥60 | 21/188 (11.2) | 21/209 (10.1) | 28/260 (10.8) | 116/188 (61.7) | 161/209 (77.0) | 163/267 (61.1) | 173/184 (94.0) | 176/203 (86.7) | 123/261 (47.1) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 9/86 (10.5) | 12/80 (15.0) | 9/85 (10.6) | 56/86 (65.1) | 60/80 (75.0) | 62/87 (71.3) | 84/85 (98.8) | 68/78 (87.2) | 57/85 (67.1) |

| Male | 57/306 (18.6) | 55/319(17.2) | 73/361 (20.2) | 182/306 (59.5) | 217/319 (68.0) | 190/369 (51.5) | 277/298 (93.0) | 253/307 (82.4) | 158/362(43.7) |

| Diagnostic group | |||||||||

| ACB | 5/99 (5.1) | 9/100 (9.0) | 12/124 (9.7) | 58/99 (58.6) | 74/100 (74.0) | 67/126 (53.2) | 93/96 (96.9) | 84/100 (84.0) | 54/122 (44.3) |

| AMI | 22/108 (20.4) | 14/97 (14.4) | 3/15 (20.0) | 71/108 (65.7) | 59/97 (60.8) | 9/15 (60.0) | 102/108 (94.4) | 75/95 (79.0) | 7/15 (46.7) |

| PCI | 16/94 (17.0) | 26/102 (25.5) | 66/297 (22.2) | 47/94 (50.0) | 70/102 (68.6) | 170/304 (55.9) | 83/90 (92.2) | 73/94 (77.7) | 148/299 (49.5) |

| Ischemia | 23/91 (25.3) | 18/100 (18.0) | 1/10 (10.0) | 62/91 (68.1) | 74/100 (74.0) | 6/11 (54.6) | 83/89 (93.3) | 89/96 (92.7) | 6/11 (54.6) |

| Total | 66/392 (16.8) | 67/399(16.8) | 82/446 (18.4) | 238/392 (60.7) | 277/399 (69.4) | 252/456(55.3) | 361/383 (94.3) | 321/385 (83.4) | 215/447 (48.1) |

*1Patient’s statement and/or >10 ppm carbon monoxide in exhaled air;

*2blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg (≥130/80 mmHg) in non-diabetics (diabetics);

*3 total cholesterol ≥175 mg/dL; ACB, aortocoronary bypass surgery; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; ischemia, myocardial ischemia.

The proportion of patients with diabetes mellitus increased sharply from 13.5% and 13.8% in EUROASPIRE I and II to 22.6% in EUROASPIRE III (p <0.001; Figure, eTable 2). The mean BMI rose from 27.7 (SD 3.3) kg/m2 in EUROASPIRE I to 28.4 (SD 3.9) kg/m2 in EUROASPIRE II and 29.7 (SD 4.6) kg/m2 in EUROASPIRE III. Correspondingly, the prevalence of obesity climbed steeply from 23.0% in EUROASPIRE I to 30.6% and 43.1% in EUROASPIRE II and III (p <0.001). Similarly, the prevalence of abdominal obesity increased from 40.3% in EUROASPIRE I to 47.1% and 51.3% in EUROASPIRE II and III (p = 0.003; eTable 3).

eTable 2. Frequency (%) of diabetes mellitus, overweight, and obesity in CHD patients from the Münster region in EUROASPIRE I, II, and III.

| Diabetes mellitus*1 | Overweight*2 | Obesity*3 | |||||||

| EUROASPIRE | EUROASPIRE | EUROASPIRE | |||||||

| I | II | III | I | II | III | I | II | III | |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| <60 | 24/204 (11.8) | 19/190(10.0) | 37/190 (19.5) | 169/204 (82.8) | 153/190 (80.5) | 160/190 (84.2) | 54/204 (26.5) | 51/190(26.8) | 95/190 (50.0) |

| ≥60 | 29/188 (15.4) | 36/209 (17.2) | 66/265 (24.9) | 154/188 (81.9) | 177/209 (84.7) | 230/267 (86.1) | 36/188 (19.2) | 71/209 (34.0) | 102/267 (38.2) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 16/86 (18.6) | 17/80 (21.3) | 24/87 (27.6) | 70/86 (81.4) | 55/80 (68.8) | 73/87 (83.9) | 25/86 (29.1) | 27/80 (33.8) | 46/87 (52.9) |

| Male | 37/306 (12.1) | 38/319 (11.9) | 79/368 (21.5) | 253/306 (82.7) | 275/319 (86.2) | 317/370 (85.7) | 65/306 (21.2) | 95/319 (29.8) | 151/370 (40.8) |

| Diagnostic group | |||||||||

| ACB | 16/99 (16.2) | 16/100 (16.0) | 38/126 (30.2) | 82/99 (82.8) | 82/100 (82.0) | 113/126 (89.7) | 19/99 (19.2) | 30/100 (30.0) | 52/126 (41.3) |

| AMI | 17/108 (15.7) | 19/97 (19.6) | 1/15 (6.7) | 89/108 (82.4) | 77/97 (79.4) | 13/15 (86.7) | 28/108 (25.9) | 27/97 (27.8) | 8/15 (53.3) |

| PCI | 7/94 (7.5) | 10/102 (9.8) | 62/303 (20.5) | 72/94 (76.6) | 86/102 (84.3) | 254/305 (83.3) | 20/94 (21.3) | 32/102 (31.4) | 131/305 (43.0) |

| Ischemia | 13/91 (14.3) | 10/100 (10.0) | 2/11 (18.2) | 80/91 (87.9) | 85/100 (85.0) | 10/11 (90.9) | 23/91 (25.3) | 33/100 (33.0) | 6/11(54.6) |

| Total | 53/392(13.5) | 55/399 (13.8) | 103/455 (22.6) | 323/392 (82.4) | 330/399 (82.7) | 390/457 (85.3) | 90/392 (23.0) | 122/399 (30.6) | 197/457 (43.1) |

*1Patient’s statement of diagnosis of diabetes mellitus by a physician;

*2body mass index ≥25 kg/m2;

*3body mass index ≥30 kg/m2; ACB, aortocoronary bypass surgery; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; ischemia, myocardial ischemia

eTable 3. Frequency (%) of abdominal overweight and abdominal obesity in CHD patients from the Münster region in EUROASPIRE I, II, and III.

| Abdominal overweight*1 | Abdominal obesity*2 | Abdominal overweight or abdominal obesity | |||||||

| EUROASPIRE | EUROASPIRE | EUROASPIRE | |||||||

| I | II | III | I | II | III | I | II | III | |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| <60 | 65/204 (31.9) | 74/190 (39.0) | 61/189 (32.3) | 87/204 (42.7) | 80/190 (42.1) | 98/189 (51.9) | 152/204 (74.5) | 154/190 (81.1) | 159/189 (84.1) |

| ≥60 | 64/188 (34.0) | 62/209 (29.7) | 80/267 (30.0) | 71/188 (37.8) | 108/209 (51.7) | 136/267 (50.9) | 135/188 (71.8) | 170/209 (81.3) | 216/267 (80.9) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 26/86 (30.2) | 19/80 (23.8) | 10/87 (11.5) | 45/86 (52.3) | 48/80 (60.0) | 68/87 (78.2) | 71/86 (82.6) | 67/80 (83.8) | 78/87 (89.7) |

| Male | 103/306 (33.7) | 117/319 (36.7) | 131/369 (35.5) | 113/306 (36.9) | 140/319 (43.9) | 166/369 (45.0) | 216/306 (70.6) | 257/319 (80.6) | 297/369 (80.5) |

| Diagnostic group | |||||||||

| ACB | 40/99 (40.4) | 28/100 (28.0) | 39/126 (31.0) | 34/99 (34.3) | 47/100 (47.0) | 67/126 (53.2) | 74/99 (74.8) | 75/100 (75.0) | 106/126 (84.1) |

| AMI | 26/108 (24.1) | 38/97 (39.2) | 7/15 (46.7) | 55/108 (50.9) | 41/97 (42.3) | 7/15 (46.7) | 81/108 (75.0) | 79/97 (81.4) | 14/15 (99.3) |

| PCI | 30/94 (31.9) | 33/102 (32.4) | 92/304(30.3) | 33/94 (35.1) | 49/102 (48.0) | 155/304 (51.0) | 63/94 (67.0) | 82/102 (80.4) | 247/304 (81.3) |

| Ischemia | 33/91 (36.3) | 37/100 (37.0) | 3/11 (27.3) | 36/91 (39.6) | 51/100 (51.0) | 5/11 (45.5) | 69/91 (75.8) | 88/100 (88.0) | 8/11 (72.7) |

| Total | 129/392 (32.9) | 136/399 (34.1) | 141/456 (30.9) | 158/392 (40.3) | 188/399 (47.1) | 234/456 (51.3) | 287/392 (73.2) | 324/399 (81.2) | 375/456 (82.2) |

*1Waist measurement ≥80 cm but <88 cm in women, ≥94 cm but <102 cm in men;

*2 waist measurement ≥88 cm in women and ≥102 cm in men; ACB, aortocoronary bypass surgery; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; ischemia, myocardial ischemia.

The frequency of treatment with antihypertensive medications increased from 80.4% in EUROASPIRE I to 88.6% in EUROASPIRE II and 94.3% in EUROASPIRE III (p <0.001), while the proportion of those taking lipid-lowering drugs rose from 35.0% to 67.4% and 87.0% (p <0.001) respectively (Figure, eTable 4). The blood pressure was under control in 39.7%, 29.2%, and 44.9% (p <0.001) of the patients taking antihypertensive medications in EUROASPIRE I, II, and III respectively (table 2). Cholesterol levels were under control in 9.7% of the patients who were taking lipid-lowering drugs in EUROASPIRE I, 20.6% in EUROASPIRE II, and 55.6% in EUROASPIRE III (p <0.001).

eTable 4. Frequency (%) of treatment with cardioprotective medications in CHD patients from the Münster region in EUROASPIRE I, II, and III.

| Thrombocyte aggregation inhibitors*1 | Antihypertensive medications*2 | Lipid-lowering drugs*3 | |||||||

| EUROASPIRE | EUROASPIRE | EUROASPIRE | |||||||

| I | II | III | I | II | III | I | II | III | |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| <60 | 167/204 (81.7) | 175/192 (91.2) | 175/188 (93.1) | 158/204 (77.5) | 164/192 (85.4) | 177/188 (94.2) | 70/204 (34.3) | 140/192 (72.9) | 167/188 (88.8) |

| ≥60 | 158/188 (84.0) | 172/210 (81.9) | 240/264 (90.9) | 157/188 (83.5) | 192/210 (91.4) | 249/264 (94.3) | 67/188 (35.6) | 131/210 (62.4) | 226/264 (85.6) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 67/86 (77.9) | 67/80 (83.8) | 79/86 (91.9) | 70/86 (81.4) | 71/80 (88.8) | 84/86 (97.7) | 32/86 (37.2) | 61/80 (76.3) | 75/86 (87.2) |

| Male | 258/306 (84.3) | 280/322 (87.0) | 336/366 (91.8) | 245/306 (80.1) | 285/322 (88.5) | 342/366 (93.4) | 105/306 (34.3) | 210/322 (65.2) | 318/366 (86.9) |

| Diagnostic group | |||||||||

| ACB | 91/99 (91.9) | 91/101 (90.1) | 118/125 (94.4) | 85/99 (85.9) | 94/101 (93.1) | 123/125 (98.4) | 30/99 (30.3) | 74/101 (73.3) | 111/125 (88.8) |

| AMI | 97/108 (89.8) | 88/98 (89.8) | 13/15 (86.7) | 90/108 (83.3) | 92/98 (93.9) | 13/15 (86.7) | 44/108 (40.7) | 67/98 (68.4) | 13/15 (86.7) |

| PCI | 78/94 (83.0) | 89/103 (86.4) | 275/301 (91.4) | 74/94 (78.7) | 90/103(87.4) | 279/301 (92.7) | 44/94 (46.8) | 73/103 (70.9) | 260/301 (86.4) |

| Ischemia | 59/91(64.8) | 79/100 (79.0) | 9/11 (81.8) | 66/91 (72.5) | 80/100 (80.0) | 11/11 (100.0) | 19/91 (20.9) | 57/100 (57.0) | 9/11 (81.8) |

| Total | 325/392 (82.9) | 347/402 (86.3) | 415/452 (91.8) | 315/392 (80.4) | 356/402 (88.6) | 426/452 (94.3) | 137/392 (35.0) | 271/402 (67.4) | 393/452 (87.0) |

*1Aspirin, other thrombocyte aggregation inhibitors;

*2beta blockers, calcium antagonists, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, diuretics, other antihypertensive medications;

*3statins, other lipid-lowering drugs; ACB, aortocoronary bypass surgery; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; ischemia, myocardial ischemia.

Table 2. Frequency of therapeutic control of blood pressure and cholesterol level in CHD patients from the Münster region in EUROASPIRE I, II, and III.

| Control of blood pressure*1 | Control of cholesterol*2 | ||||||||||||||||

| EUROASPIRE | EUROASPIRE | ||||||||||||||||

| I | II | III | I | II | III | ||||||||||||

| Age (years) | |||||||||||||||||

| <60 | 66/158 (41.8) | 61/162 (37.7) | 96/176 (54.6) | 6/69 (8.7) | 31/135 (23.0) | 87/163 (53.4) | |||||||||||

| ≥60 | 59/157 (37.6) | 42/191 (22.0) | 95/249 (38.2) | 7/65 (10.8) | 23/127 (18.1) | 126/220 (57.3) | |||||||||||

| Sex | |||||||||||||||||

| Female | 26/70 (37.1) | 15/71 (21.1) | 25/84 (29.8) | 1/32 (3.1) | 9/60 (15.0) | 26/73 (35.6) | |||||||||||

| Male | 99/245 (40.4) | 88/282 (31.2) | 166/341 (48.7) | 12/102 (11.8) | 45/202 (22.3) | 187/310 (60.3) | |||||||||||

| Diagnostic group | |||||||||||||||||

| ACB | 34/85 (40.0) | 22/93 (23.7) | 58/123 (47.2) | 2/29 (6.9) | 11/73 (15.1) | 63/107 (58.9) | |||||||||||

| AMI | 30/90 (33.3) | 34/91 (37.4) | 6/13 (46.2) | 2/44 (4.6) | 20/67 (29.9) | 8/13 (61.5) | |||||||||||

| PCI | 40/74 (54.1) | 26/89 (29.2) | 122/278 (43.9) | 7/43 (16.3) | 18/67 (26.9) | 138/254 (54.3) | |||||||||||

| Ischemia | 21/66 (31.8) | 21/80 (26.3) | 5/11 (45.5) | 2/18 (11.1) | 5/55 (9.1) | 4/9 (44.4) | |||||||||||

| Total | 125/315 (39.7) | 103/353 (29.2) | 191/425 (44.9) | 13/134 (9.7) | 54/262 (20.6) | 213/383 (55.6) | |||||||||||

*1Blood pressure <140/90 mmHg (<130/80 mmHg) in non-diabetics (diabetics) with antihypertensive medication;

*2 total cholesterol <175 mg/dL in patients with lipid-lowering drugs; ACB, aortocoronary bypass surgery; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; ischemia, myocardial ischemia.

Discussion

The EUROASPIRE I, II and III surveys in the Münster region of Germany provide data that permit the investigation of trends displayed by cardiovascular risk factors in previously hospitalized CHD patients over a period of more than a decade. The findings of the study show that the currently valid recommendations for treatment and control of cardiovascular risk factors are not always implemented in clinical practice.

The proportion of patients who were smokers changed hardly at all between 1995 and 2007, although it has long been known that giving up smoking considerably decreases the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (4, e2). Medicinal treatment and behavioral therapy greatly increase the likelihood that patients will stop smoking (15, 16, e6). Smokers with manifest CHD should be encouraged and helped to give up smoking by a combination of these strategies.

The frequency of high blood pressure did not change greatly between EUROASPIRE I and EUROASPIRE III. More than half of the participants in EUROASPIRE III had high blood pressure. These patients would benefit markedly from measures to decrease their blood pressure to values within the normal range (7, e7).

Decreasing the concentration of cholesterol is associated with reductions in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality both in patients with and in those without previous coronary disease (17, e8). The proportion of patients with high cholesterol decreased distinctly between EUROASPIRE I and EUROASPIRE III. Given that most patients in EUROASPIRE III were taking lipid-lowering drugs, it seems a further decrease in cholesterol levels can be achieved only by increasing the dosage of statins or, particularly, by bringing about changes in lifestyle.

The EUROASPIRE surveys in the Münster region show that the prevalence of diabetes mellitus has risen particularly sharply in recent years. CHD patients with diabetes mellitus have a higher risk of morbidity and mortality (18, e9– e11). In the Münster cohorts of CHD patients from EUROASPIRE I and II, diabetes mellitus was the most important predictor of cardiovascular mortality over a period of 8 years (19). An intensive treatment program featuring promotion of physical activity, changes in nutritional behavior, and smoking cessation leads to a reduction of 20% in the absolute risk of renewed coronary events in CHD patients with diabetes mellitus (20). Therefore, modification of lifestyle factors in parallel with drug treatment forms an important part of secondary prevention in such patients.

The prevalence of obesity among the EUROASPIRE survey patients in the Münster region almost doubled between 1995 and 2007. Obesity is associated with an increased risk of coronary events (21, e12, e13), and weight loss supports the prevention and control of a number of cardiovascular risk factors such as high blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, and glucose intolerance (22). Therefore, long-term reduction of body weight is a central plank in the program of secondary prevention of CHD. In general, the increased frequencies of obesity and diabetes in CHD patients reflect the epidemic of diabetes and obesity in the general population.

In 2006/07, comparing the Münster region with the averages for the other eight regions that took part in EUROASPIRE I, II, and III, the risk factors smoking, high cholesterol, and obesity were more prevalent, while high blood pressure and diabetes mellitus were less frequent (14).

Epidemiological data from another region of Germany, Augsburg, show clearly that the incidence of CHD went down by 3% per year during the 1980s and 1990s, while CHD mortality decreased by 2% annually (e14). Nevertheless, with an estimated 300 000 fatal and non-fatal cases each year, one can still speak of a CHD epidemic in Germany (e15).

A number of studies have shown the inadequate translation of scientific evidence into the clinical practice of preventive cardiology (23). It can be assumed that the treating physicians’ knowledge of existing guidelines plays a key role in the secondary prevention of CHD. A representative study of 664 general practitioners and internists in the Münster region in 2002/03 found that almost one third of them were not aware of the current guidelines for secondary prevention in CHD patients (24). A study of general practitioners in five European countries, including Germany, and a national study of physicians in the USA both yielded similar results (25, e16). The benefit of intensified promulgation of guidelines has been investigated in numerous studies. A meta-analysis of the strategies embodied in health programs for the chronically ill showed that availability of information and instruction materials for health service providers is associated with better adherence to guidelines and better treatment of the disease concerned (e17). There is an urgent need for studies investigating how best to ensure that the changes in routine practice indicated by the findings of clinical studies are actually adopted by physicians. Representative cross-sectional studies of primary care practices might yield useful data on the potential for improvement and on the impact of health care reforms (e18).

The use of standardized and practically identical interview and examination methods in all three surveys represents a crucial advantage of the EUROASPIRE study. Another advantage is that the patients were interviewed and examined no earlier than 6 months after a coronary event. This minimum period was considered long enough for implementation of secondary prevention guidelines in clinical practice. It can be seen as a limitation of our study that the patients all came from one region and were all recruited from three specialized centers. Our results therefore cannot be extrapolated to the whole of Germany. It seems likely, however, that implementation of guidelines would be poorer in regions with less specialized care. Another limitation is the difference in participation among the three surveys. The participation rates were similar in EUROASPIRE I and EUROASPIRE III, however, so systematic distortion of the observed trends between 1995/96 and 2006/07 seems improbable. Differences between patients who survived the period from coronary event to investigation in the three different EUROASPIRE surveys could also affect the trends in cardiovascular risk factors. Further limitations of our study are the definition of diabetes mellitus and the unavailability of data on nutrition and physical activity.

The results of the EUROASPIRE I, II and III surveys in the Münster region of Germany show that the targets laid out in the European guidelines are not being achieved in clinical practice. The observed trends in cardiovascular risk factors clearly show an urgent need for the strengthening of preventive strategies in patients with CHD. Control of cardiovascular risk factors by medicinal treatment and modification of lifestyle is vital to reduce the risk of further coronary events. “To salvage the acutely ischaemic myocardium without addressing the underlying causes of the disease is futile; we need to invest in prevention” (14).

Key Messages.

The prevalence of smoking among CHD patients in the Münster region who took part in the EUROASPIRE study changed hardly at all between 1995 and 2007. Almost one fifth of the participants in EUROASPIRE III were active smokers.

The prevalence of high blood pressure among EUROASPIRE patients in the Münster region changed only slightly. More than half of the study participants in 2007 had high blood pressure.

Although the prevalence of high cholesterol decreased considerably between 1995 and 2007, almost half of the EUROASPIRE III CHD patients from the Münster region had cholesterol levels ≥175 mg/dL.

The prevalence of obesity among CHD patients in the Münster region almost doubled between 1995 and 2007: 23.0% in EUROASPIRE I, 30.6% in EUROASPIRE II, and 43.1% in EUROASPIRE III.

The proportion of EUROASPIRE I, II and III patients from the Münster region who were taking antihypertensive medications was 80.4%, 88.6%, and 94.3% respectively; for lipid-lowering drugs, the figures were 35.0%, 67.4%, and 87.0%.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare.

We are particularly grateful to all of the patients who participated in the EUROASPIRE surveys. Thanks are also due to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), Sophia Antipolis, France for funding EUROASPIRE I, II, and III. Unrestricted research grants were received from MSD Sharp and Dohme, Haar (EUROASPIRE I); Pfizer, Karlsruhe and AstraZeneca, Wedel/Holstein (EUROASPIRE II); and the German Foundation for Heart Research (EUROASPIRE III). S.-M.B. and R.T. were sponsored by the EU project Network of Excellence, FP6–2005-LIFESCIHEALTH-6, Integrating Genomics, Clinical Research and Care in Hypertension, InGenious HyperCare Proposal No. 037093; S.-M.B. was also sponsored by FP7-ICT-2007–2, Project No. 224635, VPH2—Virtual Pathological Heart of the Virtual Physiological Human.

The findings were presented in part at the IEA-EEF European Congress of Epidemiology in Warsaw, Poland on 27 August 2009 and at the annual meeting of the German Society for Epidemiology in Münster on 17 September 2009.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Dr. Prugger, Dr. Heidrich, Dr. Wellmann, Prof. Brand, Dr. Telgmann, Prof. Scheld, and Dr. Kleine-Katthöfer declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Prof Breithardt acts as a consultant in advisory boards for Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Sanofi-Aventis, MSD, BMS, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Otsuka Pharma.

Dr. Reinecke acts as a consultant for Biosense Webster. He has received reimbursement of registration, travel and accommodation costs from Cordis, Daichi, Sanofi-Aventis, and Novartis; payment for lectures from The Medicines Company, Cordis, and Daichi-Sankyo; and payment for conducting commissioned studies from Bard and Sanofi-Aventis.

Prof. Heuschmann has received third-party funds for a research project he initiated from the German Foundation for Heart Research.

Prof. Keil has received fees for expert advice from Health Consumer Powerhouse Stockholm/Brussels. He has received third-party funds for a research project he initiated from Pfizer, MSD, and AstraZeneca.

References

- 1.Chambless L, Keil U, Dobson A, et al. Population versus clinical view of case fatality from acute coronary heart disease: results from the WHO MONICA Project 1985-1990. Multinational Monitoring of Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 1997;96:3849–3859. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.11.3849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins R, Peto R, MacMahon S, et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 2, Short-term reductions in blood pressure: overview of randomised drug trials in their epidemiological context. Lancet. 1990;335:827–838. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90944-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4 444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) Lancet. 1994;344:1383–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Critchley JA, Capewell S. Mortality risk reduction associated with smoking cessation in patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2003;290:86–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Lorgeril M, Salen P, Martin JL, Monjaud I, Delaye J, Mamelle N. Mediterranean diet, traditional risk factors, and the rate of cardiovascular complications after myocardial infarction: final report of the Lyon Diet Heart Study. Circulation. 1999;99:779–785. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.6.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor R, Brown A, Ebrahim S, Jolliffe J, Noorani H, Rees K. Exercise-based rehabilitation for patients with coronary heart disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am J Med. 2004;116:682–692. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: Fourth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts) Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14(suppl 2):S1–113. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000277983.23934.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.EUROASPIRE Study Group EUROASPIRE. A European Society of Cardiology survey of secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: principal results. European Action on Secondary Prevention through Intervention to Reduce Events. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:1569–1582. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.EUROASPIRE Study Group. Lifestyle and risk factor management and use of drug therapies in coronary patients from 15 countries; principal results from EUROASPIRE II Euro Heart Survey Programme. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:554–572. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.EUROASPIRE I and II Group. Clinical reality of coronary prevention guidelines: a comparison of EUROASPIRE I and II in nine countries. EUROASPIRE I and II Group. European Action on Secondary Prevention through Intervention to Reduce Events. Lancet. 2001;357:995–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enbergs A, Liese A, Heimbach M, et al. Evaluation of secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Results of the EUROASPIRE study in the Münster region. Z Kardiol. 1997;86:284–291. doi: 10.1007/s003920050060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heidrich J, Liese AD, Kalic M, et al. Secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Results from EUROASPIRE I and II in the region of Munster, Germany. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2002;127:667–672. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-23480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotseva K, Wood D, De Backer G, De Bacquer D, Pyörälä K, Keil U. EUROASPIRE Study Group EUROASPIRE III: a survey on the lifestyle, risk factors and use of cardioprotective drug therapies in coronary patients from 22 European countries. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2009;16:121–137. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3283294b1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kotseva K, Wood D, De Backer G, De Bacquer D, Pyörälä K, Keil U. EUROASPIRE Study Group. Cardiovascular prevention guidelines in daily practice: a comparison of EUROASPIRE I, II, and III surveys in eight European countries. Lancet. 2009;373:929–940. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu P, Wilson K, Dimoulas P, Mills EJ. Effectiveness of smoking cessation therapies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2006;6 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lancaster T, Stead LF. Individual behavioural counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2005 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001292.pub2. CD001292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366:1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malmberg K, Yusuf S, Gerstein HC, et al. Impact of diabetes on long-term prognosis in patients with unstable angina and non-Q-wave myocardial infarction: results of the OASIS (Organization to Assess Strategies for Ischemic Syndromes) Registry. Circulation. 2000;102:1014–1019. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.9.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prugger C, Wellmann J, Heidrich J, Brand-Herrmann SM, Keil U. Cardiovascular risk factors and mortality in patients with coronary heart disease. Eur J Epidemiol. 2008;23:731–737. doi: 10.1007/s10654-008-9291-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaede P, Vedel P, Larsen N, Jensen GV, Parving HH, Pedersen O. Multifactorial intervention and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:383–393. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hubert HB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Castelli WP. Obesity as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease: a 26-year follow-up of participants in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1983;67:968–977. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.5.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein S, Burke LE, Bray GA, et al. Clinical implications of obesity with specific focus on cardiovascular disease: a statement for professionals from the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism: endorsed by the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2004;110:2952–2967. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145546.97738.1E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lenfant C. Shattuck lecture—clinical research to clinical practice—lost in translation? N Engl J Med. 2003;349:868–874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heidrich J, Behrens T, Raspe F, Keil U. Knowledge and perception of guidelines and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease among general practitioners and internists. Results from a physician survey in Germany. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2005;12:521–529. doi: 10.1097/00149831-200512000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hobbs FD, Erhardt L. Acceptance of guideline recommendations and perceived implementation of coronary heart disease prevention among primary care physicians in five European countries: the Reassessing European Attitudes about Cardiovascular Treatment (REACT) survey. Fam Pract. 2002;19:596–604. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.6.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. Cholesterol and Recurrent Events Trial investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1001–1009. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610033351401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e2.Critchley J, Capewell S. Smoking cessation for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003041.pub2. CD003041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Pyorala K, De Backer G, Graham I, Poole-Wilson P, Wood D. Prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice. Recommendations of the Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology, European Atherosclerosis Society and European Society of Hypertension. Eur Heart J. 1994;15:1300–1331. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Wood D, De Backer G, Faergeman O, Graham I, Mancia G, Pyorala K. Prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice: recommendations of the Second Joint Task Force of European and other Societies on Coronary Prevention. Atherosclerosis. 1998;140:199–270. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(98)90209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.De Backer G, Ambrosioni E, Borch-Johnsen K, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: third joint task force of European and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2003;10(Suppl 1):1–10. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000087913.96265.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Hughes JR, Stead LF, Lancaster T. Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000031.pub3. CD000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Braunwald E, Domanski MJ, Fowler SE, et al. Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition in stable coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2058–2068. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Law MR, Wald NJ, Rudnicka AR. Quantifying effect of statins on low density lipoprotein cholesterol, ischaemic heart disease, and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003;326 doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Löwel H, Koenig W, Engel S, Hormann A, Keil U. The impact of diabetes mellitus on survival after myocardial infarction: can it be modified by drug treatment? Results of a population-based myocardial infarction register follow-up study. Diabetologia. 2000;43:218–226. doi: 10.1007/s001250050032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Miettinen H, Lehto S, Salomaa V, et al. Impact of diabetes on mortality after the first myocardial infarction. The FINMONICA Myocardial Infarction Register Study Group. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:69–75. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.Mukamal KJ, Nesto RW, Cohen MC, et al. Impact of diabetes on long-term survival after acute myocardial infarction: comparability of risk with prior myocardial infarction. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1422–1427. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.8.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Manson JE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, et al. A prospective study of obesity and risk of coronary heart disease in women. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:882–889. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199003293221303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Sullivan L, Parise H, Kannel WB. Overweight and obesity as determinants of cardiovascular risk: the Framingham experience. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1867–1872. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Tunstall-Pedoe H, Kuulasmaa K, Mähönen M, et al. Contribution of trends in survival and coronary-event rates to changes in coronary heart disease mortality: 10-year results from 37 WHO MONICA project populations .Monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 1999;353:1547–1557. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)04021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Keil U. Das weltweite WHO-MONICA-Projekt: Ergebnisse und Ausblick. Gesundheitswesen. 2005;67:38–45. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-858240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.Mosca L, Linfante AH, Benjamin EJ, et al. National study of physician awareness and adherence to cardiovascular disease prevention guidelines. Circulation. 2005;111:499–510. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154568.43333.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Weingarten SR, Henning JM, Badamgarav E, et al. Interventions used in disease management programmes for patients with chronic illness - which ones will work? Meta-analysis of published reports. BMJ. 2002;325:925–928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7370.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Koch K, Miksch A, Schürmann C, Joos S, Sawicki PT. The German health care system in international comparison: the primary care physicians´ perspective. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108(15):255–261. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]